Abstract

Background:

Mesenchymal stem cell-based treatments are now emerging as a therapy for corneal epithelial damage. Although bone marrow, adipose tissue and umbilical cord blood are the main sources of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), other tissues like the peripheral blood also harbor mesenchymal-like stem cells called peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells (PBMNCs). These blood derived stem cells gained a lot of attention due to its minimally invasive collection and ease of isolation. In this study, the feasibility of using PBMNCs as an alternative cell source to corneal limbal stem cells envisaging corneal epithelial regeneration was evaluated.

Methods:

Rabbit PBMNCs were isolated using density gradient centrifugation and was evaluated for mesenchymal cell properties including stemness. PBMNCs were differentiated to corneal epithelial lineage using rabbit limbal explant conditioned media and was evaluated by immuno-cytochemistry and gene expression analysis. Further, the differentiated PBMNCs were engineered into a cell sheet using an in-house developed thermo-responsive polymer.

Results:

These blood derived cells were demonstrated to have similar properties to mesenchymal stem cells. Corneal epithelial lineage commitment of PBMNCs was confirmed by the positive expression of CK3/12 marker thereby demonstrating the aptness as an alternative to limbal stem cells. These differentiated cells effectively generated an in vitro cell sheet that was then demonstrated for cell sheet transfer on an ex vivo excised rabbit eye.

Conclusion:

PBMNCs as an alternative autologous cell source for limbal stem cells is envisaged as an effective therapeutic strategy for corneal surface reconstruction especially for patients with bilateral limbal stem cell deficiency.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13770-020-00273-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cell sheet engineering, Corneal tissue reconstruction, Pheripheral blood stem cells, Stem cell differentiation, Thermoresponsive polymer

Introduction

The global number of the visually impaired is increasing day by day, making visual impairment an alarming scenario across the world. According to the global data of visual impairments (2015), 253 million people around the globe are suffering from some degree of vision loss [1]. Damage and injury to the eye’s outermost refracting structure, cornea, has become one among the major cause of blindness [2, 3]. Cornea being in continuous contact with the outer environment, is prone to various injuries caused by thermal or chemical insults, infections and other disease conditions [4]. Clarity of vision or visual acuity is dependent on the smoothness and degree of irregularity of the corneal surface which is maintained by the corneal layers, especially by the corneal epithelium, the outermost layer [5]. The corneal epithelium is derived from limbal stem cell pool localized in the basal epithelial layer called the limbus. Dysfunction or loss of these stem cells impairs the native corneal homeostasis resulting in a disease condition called Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency (LSCD) that can lead to partial or total blindness [6]. LSCD can cause invasion of neighboring conjunctival epithelial cells on to the corneal surface resulting in cloudiness of the cornea, chronic inflammation, vascularization, corneal scarring and even loss of vision [6, 7].

Current therapeutic strategies for LSCD include limbal graft transplantation from healthy contralateral eyes or allogenic corneal transplantation. Autologous limbal transplantation is practiced in the case of unilateral LSCD conditions while for patients with bilateral LSCD, immunologically related donors or cadaveric tissues are required for successful treatment. Despite being the most effective treatment, high probabilities for immune rejection and donor shortage remains as unmet challenges in most of the cases [8]. Therefore, alternative strategies are the need of the time and one among them is to identify alternative stem cell sources for therapeutic use in the treatment for corneal surface damage [9, 10].

Recent studies have demonstrated the successful use of mesenchymal stem cells in various cell based therapies. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are self-renewing precursor cells, with anti-inflammatory and low immunogenic properties that can be easily obtained from different tissue types [11, 12]. Peripheral blood is another source of stem cells which is easily accessible with less-invasive procedure, cost-effective and a safer source than other sources of stem cells [13]. Reports indicate that PBMNCs have similar biological characteristics to those of bone marrow-derived MSCs [11] and could be a possible alternative for use in corneal epithelial reconstruction. Unfortunately, there are few reports on the use of PBMNCs and its isolation from blood but has recently gained attention as a source of stem cells for regenerative therapy.

The purpose of this study was to isolate and characterize PBMNCs from small volumes of blood and to investigate whether the peripheral blood derived cells have the potential to be used as an alternative cell source to replace limbal stem cells in corneal surface associated therapies. For this purpose, PBMNCs were differentiated to corneal epithelial lineage and apart from demonstrating their differentiation potential, these cells were engineered in to a sheet envisaging efficient corneal epithelial transplantation. PBMNC were engineered to cell sheets by using an in house synthesized polymer (N-isopropyl acrylamide-coglycidyl methacrylate) (NGMA) by exploiting its thermo-responsive property. This polymer and its properties were previously demonstrated [14, 15] by our group and was used in the current study.

Current study made a unique attempt to differentiate PBMNCs into corneal epithelial lineage and then assess its feasibility to form a cell sheet. This corneal epithelial lineage committed cell sheets developed from peripheral blood-derived cells are intended to find its therapeutic application especially in bilateral limbal stem cell deficiency conditions.

Materials and methods

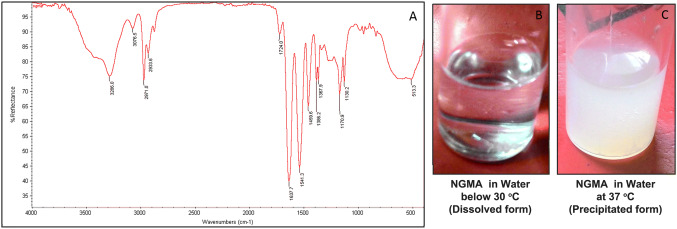

Thermo-responsive NGMA

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-co-glycidyl methacrylate (NGMA) was synthesized by free radical random polymerization of poly NIPAAm (pNIPAAm) and glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) as previously reported [14]. The NGMA was characterized by FTIR spectroscopy within IR range between 600 and 4000 cm−1 using Nicolet 5700 FT-IR spectrometer (Madison WI) with Diamond ATR accessory.

Isolation and culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were isolated from rabbit blood with approval from The Institute Animal ethical committee (IAEC) of Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology. Blood (5–7 mL) was collected from marginal ear vein of 5–8 months old healthy New Zealand white rabbits. The PBMNCs were obtained by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, 3 mL of blood was layered on to histopaque-1077 and centrifuged at 400 g for 30 min. PBMNCs found at the interface of plasma and histopaque were collected in a fresh tube and pelleted by centrifugation. The cells were resuspended in Minimum essential medium alpha (αMEM, Gibco Invitrogen, Thermoscientific, Grand Island, NY, USA), containing 10% FBS (Gibco Invitrogen) and 100 IU/mL penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco Invitrogen, Thermoscientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were seeded in T25 culture flask (Nunc -Thermo Fisher Scientific , PuDong, SH, China) and incubated at 37 °C in a 95% humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 (Sanyo, Osaka, Japan). The plated cells were kept undisturbed for 5–7 days and from then, the growth medium was replaced every 3 days.

Characterization of PBMNCs

Population doubling time and colony forming assay

To determine the proliferative potential of PBMNCs, cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells in standard tissue culture dishes. After 72 h, the cells were trypsinized with 0.25% Trypsin (Gibco Invitrogen) and the number of cells were counted using a hemocytometer. The cells were then reseeded at the initial cell density. This procedure was repeated until passage 8 and the population doubling time (PDT) was calculated using the formula,

where T and T0 represent the final and initial time respectively. N0 and Nt are the number of cells before and after each passage.

Colony forming assay was performed by plating PBMNCs from passages (P) at early (P2), middle (P5) and late (P10) stages. Cells were seeded at a density of 200 cells per dish and cultured for 14 days under standard culture conditions. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained with 0.5% Crystal violet (Glaxo Laboratories India) to count the number of cell colonies. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33,258 (Sigma, India) and the number of cells within each colony were counted under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 6000, Germany).

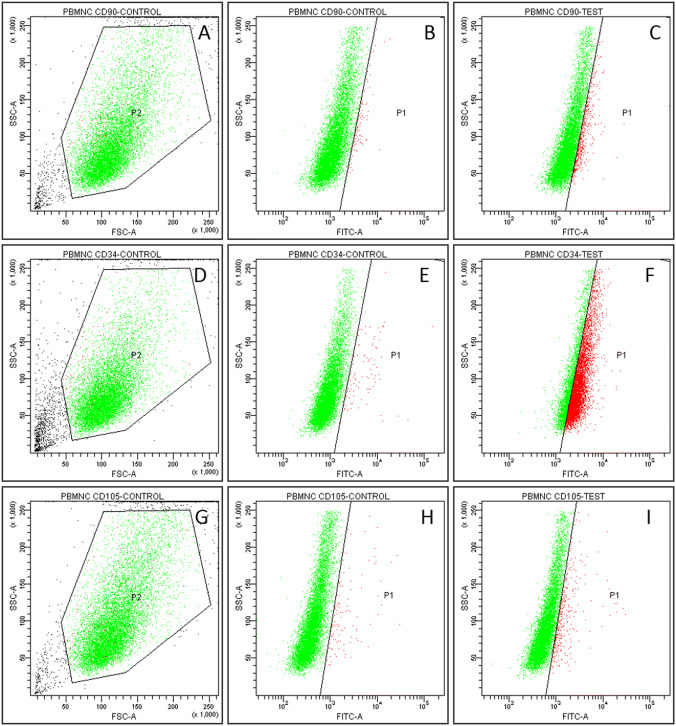

Flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry analysis

Cells at third passage were trypsinized and the culture medium was replaced with 4% PFA to fix cells in suspension. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, India) for 5 min and non-specific binding sites were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (Sigma, India). The cells were incubated with the primary antibodies (CD105, CD90 and CD34) for 1 h at room temperature and then with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) after rinsing with PBS. The cells were resuspended in PBS and analysed in a Flow Cytometer (BD FACS Aria, USA). Details of the antibodies used and staining conditions are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of antibodies used in the study

| Cell marker | Primary antibody | Secondary antibody |

|---|---|---|

| CD105 | SC-71042, Santa Cruz biotechnology | ab150157, Goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam |

| CD90 | ab225, Abcam | ab150117, Goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam |

| CD34 | ab6330, Abcam | ab150117, Goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam |

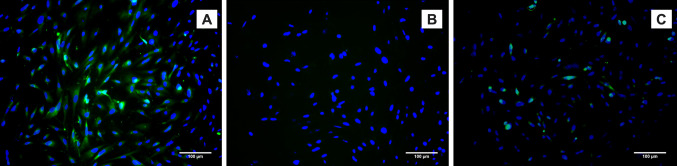

PBMNCs at passage four (P4) grown on glass coverslips were used for immunofluorescence staining. Cells were fixed using 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X-100 and non-specific binding sites were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies CD105, CD90 and CD34 followed by the FITC tagged secondary antibody as described above. The cell nuclei were counterstained with 100 μM Hoechst 33,258. Samples were observed under fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 6000, Switzerland) and images were captured using Leica Application Suit Software.

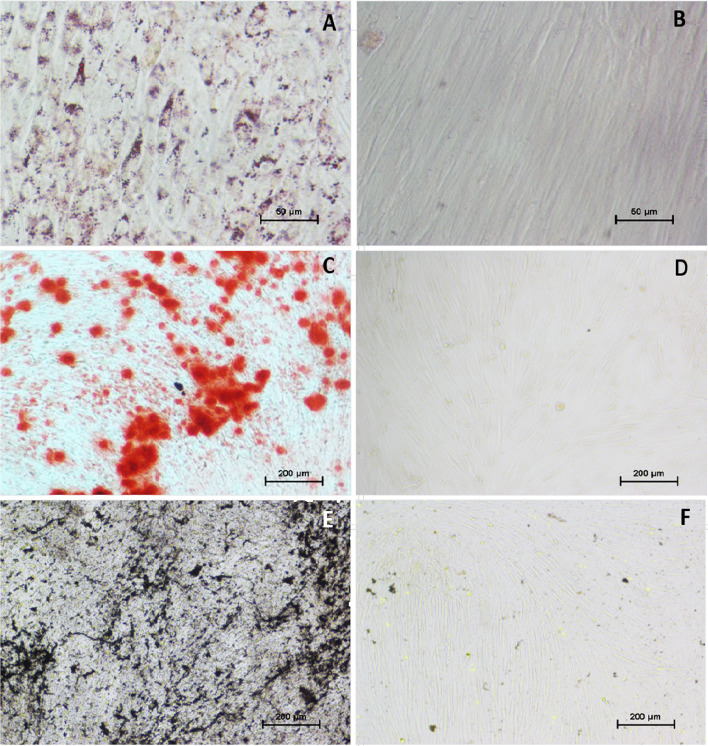

Multilineage differentiation

Multilineage differentiation potential of PBMNCs was evaluated by inducing Adipogenic and Osteogenic differentiation in PBMNCs. Cells at P4 were treated with adipogenic differentiation medium (Stempro, Gibco) for 21 days and osteogenic induction medium (Stempro, Gibco) for 28 days at standard culture conditions. PBMNCs cultured in DMEM for the same duration were considered as control. The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA. Cells differentiated to adipose lineage were stained with Oil Red O (Nice Chemicals) to demonstrate lipid deposition. Cells were incubated for 5 min in 60% isopropanol and then stained with Oil Red O solution (3% in isopropanol: distilled water at 3:2 ratio) for 10 min. The cells differentiated to osteogenic lineage was evaluated for extracellular mineralization by Alizarin red and Vonkossa staining. The osteogenic cells were stained with 1% Alizarin red (Sigma, India) to determine calcium deposition. Mineralization of osteogenic induced cells were evaluated by staining fixed cells with 5% silver nitrate (Merck, India) followed by exposure to UV light for 5 min. The stained cells were observed under light microscope (TS-100, Nikon Japan) and images were captured.

Differentiation of PBMNCs towards corneal epithelial lineage

Differentiation of PBMNCs cultured to corneal epithelial lineage on NGMA dishes was achieved by incubating the cells with limbal epithelial cell conditioned media as described below.

Preparation of limbal epithelial conditioned medium

Cornea was collected from rabbit cadavers that were used as control groups in other experiments after euthanization, with approval from Institute animal ethics committee (IAEC). The cornea was excised and collected in sterile PBS containing antibiotics. The limbal region was separated from cornea and cut into small pieces (2 × 2 mm) to use as explants. The explants were carefully placed on 35 mm culture dishes (Nunc) and were supplemented with Eagle’s minimum essential medium (Sigma) containing 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 300 mM glutamine. Explants were incubated at 37 °C in 95% humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 until the cells reached 70% confluency. The culture medium was collected at every 48 h and replaced with fresh medium. The collected medium was filtered using 0.2 µm syringe filter (Millex GP, Millipore India) and stored at – 80 °C. Later this medium was diluted with α- MEM complete medium (3:1 dilution) and is further mentioned as conditioned medium.

Differentiation of PBMNCs with corneal epithelial paracrine cues

PBMNCs at P4, seeded on NGMA dishes (2 × 104 cells/60 mm dish) were differentiated to corneal epithelial lineage by treating with limbal epithelial conditioned medium for 14 days. The medium was changed once in three days and cells were observed under an inverted phase contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS 100).

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry analysis

The PBMNCs differentiated to corneal lineage were fixed in 4% PFA and analyzed for the expression of corneal epithelial characteristics. After permeabilization and blocking, the cells were incubated with primary antibody against Cytokeratin 3/12 (CK3/12, Abcam, ab68260) for 1 h, washed and incubated with the secondary antibody (anti-mouse FITC). The cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33,258 and viewed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 6000, Germany). Differentiated cells were also analyzed using FACS for CK3/12 as per protocol mentioned above.

Gene expression analysis

PBMNCs treated for 14 days using limbal condition medium were used to characterize differentiation at the gene expression level. Cells maintained for the same duration in normal growth medium for 14 days were considered as control. Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol® (Ambion™) as per manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using Nano drop (ND 1000, Thermo Scientific). cDNA was synthesized from 1ug of RNA with Superscript III reverse transcriptase (11,752–050, Invitrogen) in a 20 µL reaction using a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Germany). The cDNA was amplified using specific primers (IDT, USA) in a Roche light cycler® 96 real-time PCR system. The primer sequences are given in Table 2. The amplified cDNA was quantified by SYBR green technology using Kapa SYBR® Fast qPCR Master Mix (KK4609–07959478001, Kapa Biosystems). 2−ΔΔC(t) method was used for relative quantification of gene expression with GAPDH as the housekeeping gene. Cycling conditions were as per Kapa SYBR® Fast qPCR Master mix protocols for Roche light cycler® 96. The relative gene expression is represented as fold change and the data is expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Table 2.

The primers and sequences

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| CK 3 Forward | GACTCGGAGCTGAGAAGCAT |

| CK 3 Reverse | CAGGGTCCTCAGGAAGTTGA |

| CK 12 Forward | GAGCTGGCCTACATGAAG |

| CK 12 Reverse | TTGCTGGACTGAAGCTGCTC |

| P63 Forward | TGTGTTGGAGGGATGAACCG |

| P63 Reverse | CACCGTTCTTTGTGCTGTCC |

| PAX 6 Forward | CGGGAAAGACTAGCAGCCAA |

| PAX6 Reverse | TGGTTGGTAGACACTGGTGC |

| CK 19 Forward | CTACAGCTATCGCCAGTCGT |

| CK 19 Reverse | TTGGAGTTCTCAATGGTGGCA |

| GAPDH Forward | CAACGAATTTGGCTACAGCA |

| GAPDH Reverse | AAACTGTGAAGAGGGGCAGA |

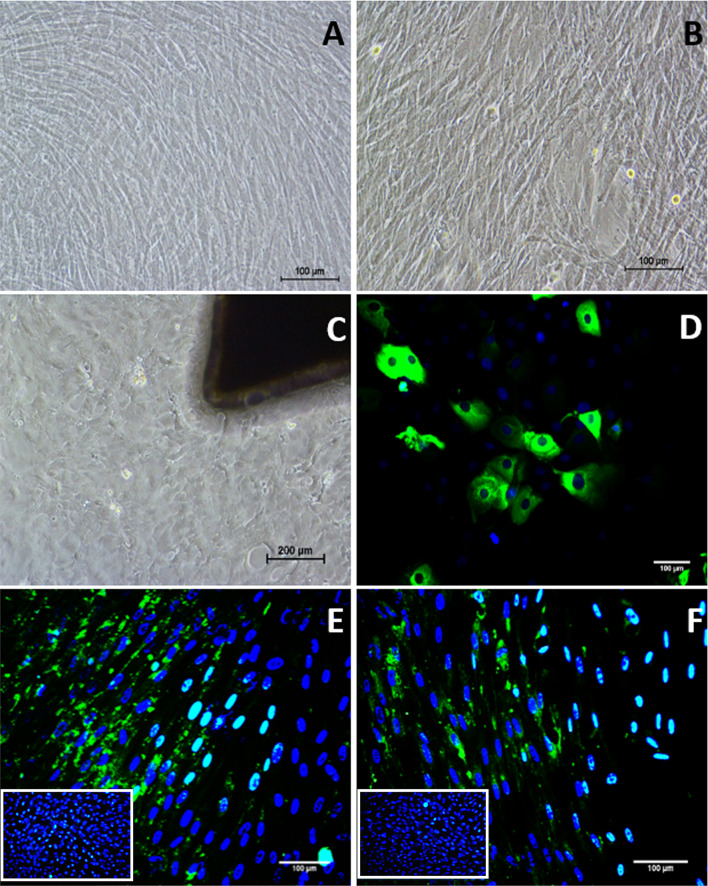

Cell sheet engineering

The PBMNCs at P4 were cultured on NGMA coated dishes and at confluency they formed interconnected sheet-like structures on the polymer coated culture surface. When the cell-seeded NGMA coated dishes were incubated at less than 20 °C for 5–10 min, the cells detached as a sheet and was monitored under phase contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TS 100). The detached cell sheets were transferred into a fresh 35 mm culture dish to demonstrate cell sheet transfer. The cells in the sheet reattached to the new surface and incubated in growth medium.

The viability of cell sheet before and after transfer to a new substrate was assessed by calcein AM staining (C1430 Thermo Fisher scientific). The cell sheet was treated with calcein-AM (1:1000 dilutions in complete medium), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 6000, Germany) using a blue filter. The cytoskeletal morphology of the differentiated PBMNC sheet was determined by Actin Green 488 Ready Probes reagent (R37110, Thermo Fisher scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33,258 and the cell sheet was viewed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 6000, Germany).

Demonstration of cell sheet transfer ex vivo

To demonstrate cell sheet transfer and its clinical relevance as a therapy for corneal reconstruction, an ex vivo rabbit eye was prepared. The corneal surface was damaged using 0.5 N sodium hydroxide and the damage was then demonstrated using OptiGlo fluorescein sodium ophthalmic strip USP (Ophtechnics Unlimited, India). The cell sheets harvested from the NGMA was transferred on to the ex vivo corneal surface damage for demonstration of cell sheet transfer.

Results

Thermo-responsive polymer NGMA: synthesis and characterization

Polymer NGMA is the product of free radical random polymerization of pNIPAAm and GMA. The copolymer formation was confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy which depicted the peaks corresponding to the amide group of pNIPAAm at 1635 cm−1, 1540 cm−1 and 1458 cm−1. The spectrum also confirmed peaks of GMA at 838 cm−1, 925 cm−1 and 978 cm−1, which represents the epoxy group (Fig. 1). The thermo-responsive behavior of the copolymer was demonstrated by its change in property in response to temperature. At a temperature below 30 °C, NGMA remain soluble and formed a clear solution with water (Fig. 1B) whereas at 37 °C, it formed an insoluble white precipitate with water (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

NGMA characterization A FT-IR spectrum depicting peaks corresponding to amide group of pNIPAAm at 1635 cm−1, 1540 cm−1 and 1458 cm−1; peaks representing the epoxy ring of GMA is shown at 838 cm−1, 925 cm−1 and 978 cm−1. Phase transition of NGMA in water B soluble clear form at temperature below 30 °C C Precipitated white colored formed at 37 °C

Isolation of PBMNCs from rabbit blood

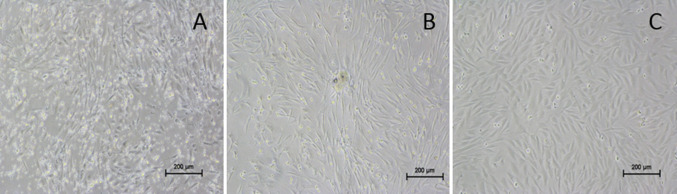

The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from the whole blood of rabbits. Individual heterogeneous cells were observed within 72 h of incubation under standard culture conditions. After 5 to 7 days of incubation, small colonies with fibroblast-like morphology and intermittent colonies with cobble stone morphology (Fig. 2A, B) were observed. On subculture at 80% confluency, the colonies with cobblestone cell morphology gradually disappeared forming only confluent fibroblast-like cells. After 3rd passage, the cells in the culture became homogenous and fibroblastic in morphology (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Morphology of PBMNCs under phase contrast microscope. A Appearance of cells with fibroblast- like morphology after 7 days of isolation. B 12 days of isolation, C fibroblast like cells in passage 3

Characterization of PBMNCs

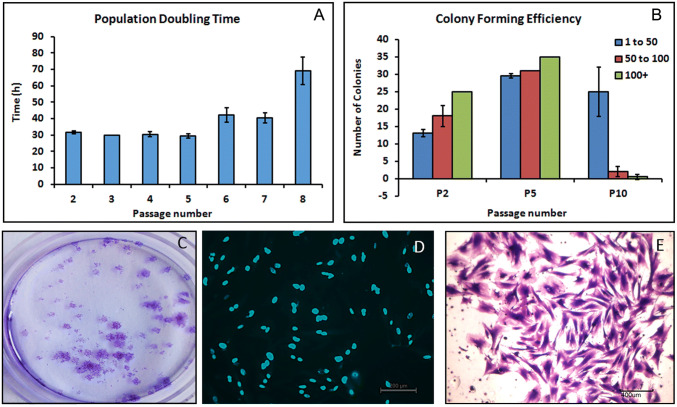

Population doubling time and colony forming unit assay

Population doubling time (PDT) was almost consistent from passages P2–P5 and began to change from P6 and then rapidly increased after P7. This indicates consistent proliferation potential up to P5 and subsequent decrease in proliferation rate thereafter. The trend of PDT versus passage number is given in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

PBMNC cell behavior A graph showing population doubling time of PBMNCs in different passages B graph showing colony forming efficiency of PBMCs in different passages C gross image of PBMNC colonies stained with crystal violet. Arrow mark indicates a colony stained with crystal violet D Hoechst staining of cells in colonies E Crystal violet staining of cells in colonies

The colony forming efficiency of PBMNCs were evaluated and colonies were classified as small, medium and large depending upon the number of cells per colonies. Colonies with less than 50 cells were considered small colonies, 50–100 as medium and above 100 cells as large colonies. The proliferating potential of cells decreased during passaging. The cells from P5 showed more proliferating potential and colony forming ability than cells from P10. Early P2 and late P10 passages showed limited colony forming potential when compared to P5 indicating significant variations in colony forming efficiency between passages (Fig. 3B). The number of colonies formed was determined by manual counting of the crystal violet stained colonies (Fig. 3C). Supplementary figure 1 displays crystal violet stained colonies of small, medium and large size based on the number of cells present in each colony. Cell number was determined by Hoechst staining (Fig. 3D) and reconfirmed by crystal violet staining (Fig. 3E).

Flow cytometry analysis and Immunocytochemistry

Cell phenotype of the PBMNCs were characterized using flow cytometry by analyzing expression of CD90, CD34 and CD105 markers. 67 ± 2% cells in P4 passage were found positive for CD34 (Fig. 4) but less than 20% were positive for both CD90 (Fig. 4A–C) and CD105 (Fig. 4G–I). Immunostaining of cultured PBMNCs also indicated CD34 positive staining (Fig. 5A) but were found to be negative for CD90 (Fig. 5B) and CD105 (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometry analysis for characterization of PBMNCs. A–C CD90 staining of PBMNC (A) scatter plot, FSC versus SSC (B) Gated population of secondary stained control (C) gated positive population for CD90 < 20%. D–F CD34 staining of PBMNC (D) dot plot FSC versus SSC (E) Gated population of secondary stained control (F) gated positive population for CD34—67.5% G–I CD105 staining of PBMNC (G) dot plot, FSC versus SSC (H) Gated population of secondary stained control (I) gated positive population for CD105 < 20%

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining of PBMNCs showing positive expression of A CD34 and negative for B CD90, C CD105

Multi-lineage differentiation

The multi-lineage differentiation potential of PBMNCs were studied using differentiation specific medium. The presence of lipid vacuole accumulation in adipogenic induced PBMNCs confirmed using Oil Red O staining indicated the adipogenic differentiation potential of PBMNCs (Fig. 6). The absence of lipid accumulation in the non-induced cells confirmed directed differentiation (Fig. 6B). The osteogenic differentiation potential was confirmed by the presence of mineralized calcium and phosphorus deposition. PBMNCs cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium stained with Alizarin Red (Fig. 6C) and von Kossa (Fig. 6E) confirmed the osteogenic differentiation potential of PBMNCs. Whereas non induced cells were negative for Alizarin Red (Fig. 6D) and von Kossa (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Multi-lineage differentiation of PBMNCs; A Oil red O staining showing lipid droplet accumulation in adipogenic differentiated PBMNCs, B Oil red O staining on non-induced PBMNCs. C Alizarin red staining giving brick red color deposition on cells due to mineralization indicating osteogenesis, D Alizarin red staining on non-induced PBMNCs, E von Kossa staining giving dark color deposition on cells due to mineralization indicating osteogenesis, F von Kossa staining on non-induced PBMNCs

Differentiation of PBMNCs towards corneal epithelial lineage

PBMNCs were incubated with limbal epithelial conditioned medium for 14 days in standard culture conditions. The conditioned medium from the limbal explant cultures were collected and pooled to provide the paracrine cues to PBMNC for differentiation towards corneal epithelial lineage.

Morphology of the differentiated PBMNCs were found to be slightly broader in shape (Fig. 7) when compared to the non-induced cells (Fig. 7A). Differentiation of PBMNCs to corneal epithelial lineage was achieved by using conditioned medium collected from the limbal explant culture. 2 mm limbal explants from rabbit models were cultured in standard conditions and cells started migrating on to the culture dish from the explant as demonstrated (Fig. 7C). The limbal explant culture demonstrated heterogeneous morphology of cells, containing various cell types including corneal epithelial cells that express terminal differentiation marker CK3/12 (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Corneal epithelial differentiation: A Phase contrast image of non-induced PBMNCs. B Phase contrast image of corneal epithelial differentiated PBMNCs, C Phase contrast image limbal explant derived cells, D CK3/12 Immunocytochemistry staining of limbal explant derived cells (E and F) CK3/12 ICC imaging of corneal epithelial differentiated PBMNCs. Images in the inset shows CK3/12 staining of non-induced cells

Detection of CK3/12 by immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry

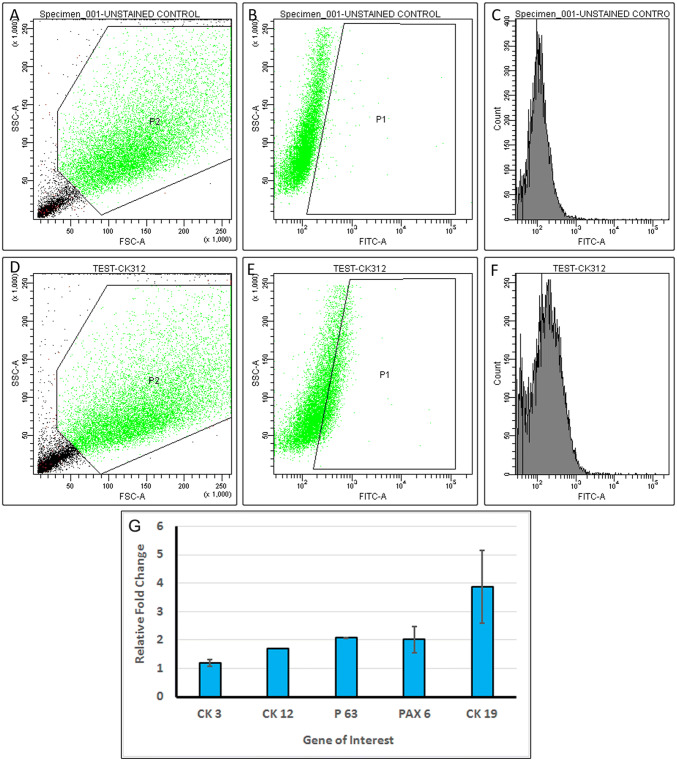

PBMNCs differentiated using limbal conditioned medium to corneal epithelial lineage was characterized by the expression of corneal epithelial marker CK3/12. The differentiated cells showed positive expression of CK3/12 (Fig. 7E, F) compared to undifferentiated cells. Images of CK3/12 staining of undifferentiated cells are given in the inset of Fig. 7E, F. Flow cytometric analysis showed that 13.95 ± 1.7% (Fig. 8) of cells expressed the terminal differentiation marker CK3/12. Figure 8A shows the FSC versus SSC distribution pattern of the non-induced cell population. The non-induced cells cultured in normal growth medium for 14 days were used as a negative control (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Flow cytometry analysis for differentiation of PBMNCs: A–C non induced cell population (A) Scatter plot, FSC versus SSC of non-induced PBMNC (B) Gated population of non-induced (control) cells for CK 3/12 staining (C) Histogram of non-induced (control) cells for CK 3/12 staining. D and E Corneal epithelial differentiated PBMNCs. A Dot plot, FSC versus SSC of induced PBMNC (E) Gated population of induced PBMNCs for CK 3/12 staining (F) Histogram of corneal epithelial differentiated PBMNCs—13.95%. G Corneal epithelial gene expression of PBMNCs cultured for 14 days in limbal explant condition medium. The data (n = 3) is represented as mean ± SD

Gene expression analysis

Quantitative PCR analysis demonstrated the role of limbal conditioned medium in directing PBMNCs to corneal epithelial lineage. After 14 days of the induction period, various epithelial lineage related markers were found to be upregulated when normalized to non-induced controls. Corneal epithelium-specific gene, CK12 showed almost two-fold increase in comparison to the non-induced PBMNCs while CK3 even though upregulated was not significantly high. The p63 gene that is involved in homeostatic renewal of corneal epithelium and PAX6 gene responsible for corneal morphogenesis was also upregulated approximately two folds. The limbal conditioned medium provided the required differentiation cues to PBMNCs for differentiation to epithelial lineage as evidenced by three to fivefold upregulation of CK19. The fold change in the gene expression of differentiated PBMNCs is shown in (Fig. 8G).

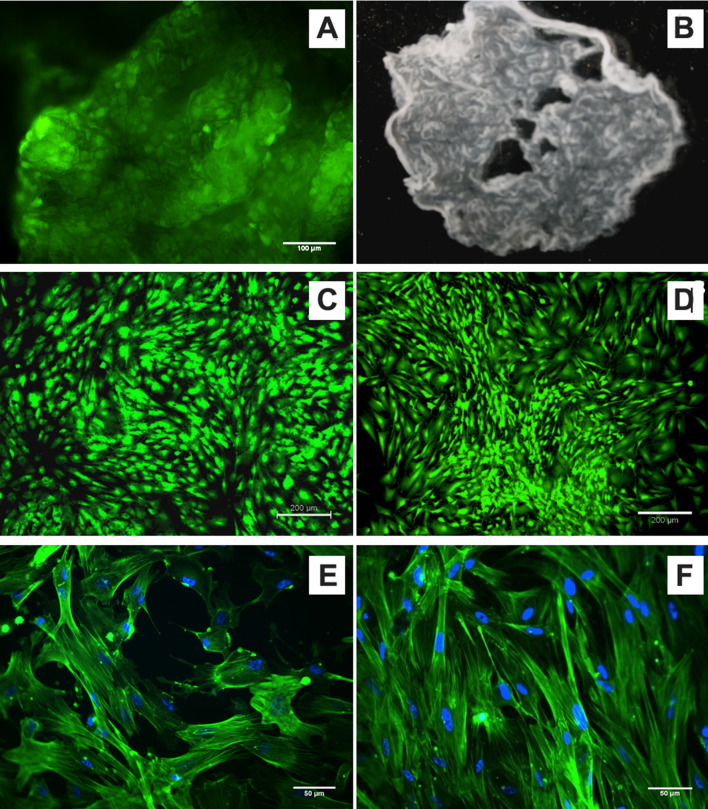

Cell sheet engineering

PBMNCs cultured on NGMA coated dishes attached, proliferated and attained confluence as on normal culture dishes. NGMA coated dishes undergo a phase transition at lower temperatures and this change in the surface property of NGMA makes the cell sheet detach from the polymer surface. The cells were detached as a sheet from NGMA surface upon incubation at temperature below 20ºC. The viability staining of the cell sheet showed viable cell population in the detached cell sheet (Fig. 9A). The Stereo microscopic image of the cell sheet provides the gross structure of the cell sheet (Fig. 9B). The detached sheet was then transferred to a fresh normal cell culture dish where it reattaches and grows as normal. The viability of PBMNCs before cell sheet retrieval (Fig. 9C) and after reattachment to a new dish (Fig. 9D) was also confirmed by calcein AM staining. The cytoskeletal distribution of cells in the transferred cell sheet confirmed that the detachment and re-adherence of cell sheet has not affected the cell morphology (Fig. 9E, F).

Fig. 9.

Evaluation of PBMNC Cell sheet (A) Calcein AM staining of a detached/ floating cell sheet (B) stereo microscopic image of a floating sheet (C) Calcein AM staining of cells on NGMA before detaching (D) Calcein AM staining of cells after reattaching to a new dish (E) Actin cytoskeletal staining of cells on NGMA (F) Actin cytoskeletal staining of cells after transfer to a new dish

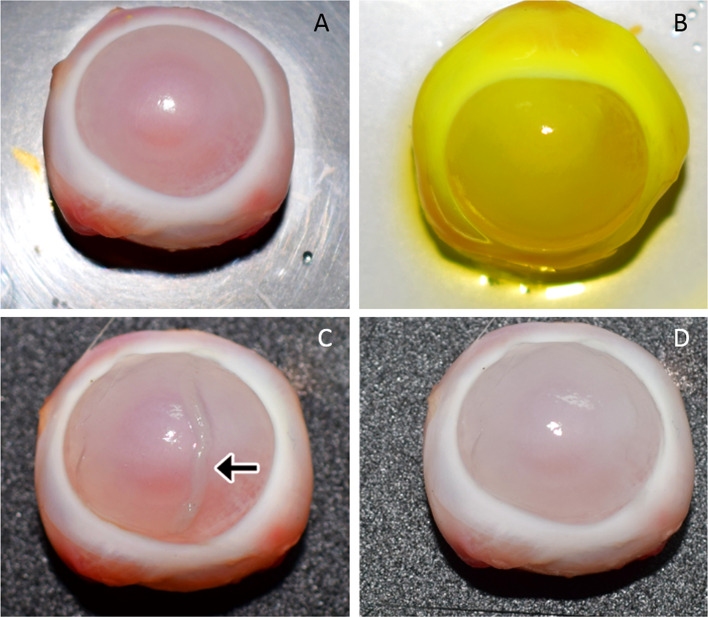

Demonstration of cell sheet transfer

Cell sheet transfer to a damaged corneal surface was demonstrated by an ex vivo experiment. Excised rabbit eye was used to create alkali-induced corneal damage (Fig. 10A). Sodium fluorescein dye uptake confirmed the ocular surface damage (Fig. 10B). PBMNC cell sheet transfer was demonstrated with the ex vivo model (Fig. 10C) and the transferred sheet was found to be intact and transparent (Fig. 10D), representing a successful cell sheet development and transfer.

Fig. 10.

Demonstration of cell sheet transfer (A) ex vivo excised rabbit cornea with debrided epithelium (B) sodium fluorescein stained damaged cornea (C) transplantation of cell sheet (indicated by arrow mark) on to the damaged cornea (D) cornea after transfer of PBMN cell sheet

Discussion

Stem cells from various sources are used as an effective therapeutic tool in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine and these include epithelial, mesenchymal, embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells [16]. Mesenchymal stem cells especially adipose and bone marrow stem cells have shown immense potential [17, 18], however, in most cases the harvesting process involves invasive procedures, high risk of infections and severe pain to the individuals [19]. Due to these drawbacks, peripheral blood mononuclear cells represents a superior cell source to other cell sources in tissue engineering applications in terms of ease of isolation and it represents an accessible autologous cell population for therapeutic purpose.

The current work proposed the use of peripheral blood from the marginal ear vein of rabbits for isolating PBMNCs by a density gradient centrifugation method which is widely practiced [20, 21]. Attempts were made to demonstrate the behavioral properties of peripheral blood stem cells in a step wise manner. The isolated cells in P0 passage were heterogeneous with fibroblast-like and cobblestone shaped cells. After an initial expansion, during the subsequent passaging the cobblestone shaped cells were lost and fibroblast-like cells became prominent. Further analysis of PBMNCs showed almost similar characteristics of MSCs, supporting the mesenchymal origin of PBMNCs. As in MSCs, PBMNCs also exhibited plastic adherence property and colony forming potential [22] with later passages showing signatures of senescence [23, 24]. Another similarity of PBMNCs with MSCs is their potential to differentiate to multiple lineages including adipo-, osteo-, and chondro-genic lineages [25]. In the current study, muti-lineage differentiation potential of PBMNCs was also demonstrated and they displayed altered morphology and retarded growth rate from passage 7 onwards indicating senescence.

Based on the cluster of differentiation markers, PBMNCs were characterized broadly into CD34 positive population or CD34 negative population [13, 26]. There are reports suggesting that PBMNCs express similar set of markers as that of MSCs and can be considered as a subclass of MSCs [27]. These blood-derived cells are also called circulating MSCs, which is expected to be mobilized from bone marrow and other sites in to the blood [28]. We observed that these cells were mostly CD34 positive and expressed less than 20% positivity for MSC markers CD90 and CD105 at passage 3. Expression of CD34 marker does not make PBMNCs non-mesenchymal, as there are increasing evidences and arguments suggesting that MSCs are CD34 positive [29]. It is stated that resident MSCs are CD34 positive and in vitro expanded MSCs become CD34 negative due to the change in their mechanical environment [30]. It was also reported that freshly isolated CD34 positive PBMNCs turned CD34 negative with increased levels of MSC markers with further passaging [27]. From these observations, we can consider PBMNCs as hematopoietically derived CD34 positive mesenchymal precursors as reported by Hu et al., 2011 [24]. All these aforementioned properties along with the presence of CD34 positive cell surface marker suggests that PBMNCs may be mesenchymal precursor cells in a hematopoietic stem cell pool. Considering the above discussed observations, the current study recommends to consider PBMNCs similar to cells of mesenchymal origin as reviewed in other articles those compare PBMNCs to mesenchymal stem cells [13, 24, 25].

Apart from displaying mesenchymal stem cell like properties, PBMNCs can be harvested from the body through a less invasive simple method like phlebotomy [18]. This is cost-effective, requiring no sophisticated setup, no surgical procedure tables and is minimally time-consuming for harvesting cells from the body when compared to isolation of MSCs from any other source. Being demonstrated that PBMNCs exhibit MSC like properties and are easily isolated, they were further analyzed to determine the possibility of differentiating towards corneal epithelial lineage. PBMNCs have been previously reported to enhance cartilage repair in in vivo models and has also been shown to be therapeutically effective for the treatment of limb ischemia [27, 31]. Differentiation to corneal epithelial lineage was achieved by incubating PBMNCs with limbal conditioned medium where the limbal explant secretome induce epithelial lineage commitment as reported previously [32, 33]. Immunocytochemistry studies indicated the presence of CK3/12, a terminal differentiation marker restricted to corneal epithelial cells in vertebrates [34, 35]. Gene expression studies also showed upregulation of CK3 and CK12 genes when induced with limbal conditioned medium. Upregulation of PAX 6 and p63 are also indications towards epithelial lineage commitment of differentiating PBMNCs. Paired box homeotic gene 6 (PAX 6) is required for proliferation, differentiation and normal development of corneal epithelium [36]. p63 is a corneal epithelial stem cell marker with maximum expression in the limbal region [37]. CK19 is a conjunctival epithelial marker found in limbus and peripheral cornea [38]. Upregulation of these markers indicated the epithelial lineage commitment potential of differentiating PBMNCs. This ability of PBMNCs can be exploited, while considering these cells as an alternative cell source to limbal stem cells in corneal regenerative therapies especially in LSCD conditions.

Repair and regeneration of corneal epithelium is swiftly carried out by body's innate response to injury and regeneration and is performed by a specialized group of stem cells called limbal stem cells residing in the corneoscleral junction [39]. Any damage to these cells affects the normal regeneration mechanism leading to corneal damage and vision loss [40]. In most severe cases of limbal damage, like bilateral limbal stem cell deficiency, a limbal stem cell/limbal graft therapy is performed from allogeneic sources. These methods hold disadvantages of non-availability of healthy donor tissue and also immune rejection and requires immune-suppression therapies [4]. Autologous alternate cell sources can play a significant role in corneal surface reconstruction as they avoid chances of immune rejection and can always be harvested from a healthy individual [41]. PBMNCs with the potential to express corneal epithelial markers can be promising candidates in the group of alternative non-ocular stem cell sources with the advantage of ease of access and harvesting. Apart from identifying PBMNCs as a source, a mode of delivery of these cells to the corneal surface was also demonstrated in this work for hassle-free clinical procedures with enhanced transplantation efficiency. Mode of transfer without loss of cells and cellular function is important for successful transplantation. Currently, the direct injection of cells to the target site or cell transplantation supported by carrier scaffolds is followed in cell transplantation therapy for cornea [42]. But the major drawbacks of these methods are poor cell survival in damaged site and career scaffold induced inflammatory problems. Cell sheet engineering is a promising method which enables enhanced donor cell presence in the damaged area [43]. PBMNC cell sheets were achieved using an in-house developed thermo-responsive polymer, NGMA. NGMA is a copolymer of pNIPAAm and GMA and its properties were previously demonstrated by our group in both in vitro and in vivo applications [14, 15, 17]. It is also reported that cell sheet retrieved from NGMA recovers ocular surface damage in animal models [44]. pNIPAAm is a well-demonstrated thermo-responsive polymer and is used for corneal epithelial sheet generation in corneal surface reconstruction procedures [45]. Transplantation of cells as a sheet offer several advantages over other methods as the cells are in tight contact with each other, maintain cell–cell junction, cell surface proteins, and the extracellular matrix remains intact. This enables maximum cell density and direct transplantation to the target site without any sutures [46].

This is one of the first reports to demonstrate peripheral blood mononuclear cell sheets using a thermo-responsive cell culture surface. The sheets thus developed were also demonstrated for their integrity, compatibility and potential to use in transplantation procedures. The cell sheet developed on NGMA surface was transferred to new substrates and was demonstrated for their viability and morphology. The detached cell sheet was viable and the cells within the sheet seemed to have round morphology. The reattached cell sheets were found to be viable and maintained their cytoskeletal morphology. The transfer of cell sheet to ex vivo LSCD eye of rabbit with a damaged corneal surface shows that mechanical manipulation of retrieved cell sheet is not affecting the integrity after transfer. Cell sheet transfer was successful technically, thereby demonstrating a novel strategy for corneal surface reconstruction.

In conclusion, use of PBMNCs as an alternative cell source with additional benefits such as potential to differentiate to corneal epithelial lineage along with cell sheet formation ability will be a logical and implementable approach to treat bilateral LSCD in regenerative therapy in near future. Further, moving on to in vivo studies for evaluating the functional efficacy of the PBMNC sheet, it would be interesting to characterize the limbal condition medium and then fine tune differentiation by selecting specific differentiation cues. It would be also beneficial to identify the functional role of each corneal epithelial differentiation markers in the functional survival of the cell sheet on the cornea injury surface and to modulate their expression accordingly. PBMNCs allow a noninvasive cell harvesting method along with exhibiting multi-lineage differentiation potential and cell sheet formation ability which allows greater donor cell presence in damaged sites makes this cell source a vital player in the near future of regenerative cell therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Figure 1: PBMNC colonies stained with crystal violet. (A) Colonies with less than 50, considered small colonies (B) Colonies with cells between 50 and 100, considered as medium sized colonies (C) Colonies with more than 100 cells, considered as large colonies (TIF 960 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Department of Science and Technology, Goverment of India (SR/SO/HS-0042/2012). The authors acknowledge the technical support extended by Dr. Sachin J. Shenoy and Mr. Manoj for collection of rabbit blood, cornea and Ms. Deepa K. Raj for the flow cytometry experiments.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The study involving collection of cornea and blood from rabbits were approved and monitored by the Institute Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology (SCT/IAEC-060/AUGUST/2013/81).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Balu Venugopal and Sumitha Mohan have equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1.Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, Das A, Jonas JB, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e888–e897. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay MP. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Tandon R, Gupta SK, Sreenivas V, Vashist P. Burden of corneal blindness in India. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:198–206. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.120153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saghizadeh M, Kramerov AA, Svendsen CN, Ljubimov AV. Concise review: stem cells for corneal wound healing: stem cells for corneal wound healing. Stem Cells. 2017;35:2105–2114. doi: 10.1002/stem.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfister RR, Burstein NL. The normal and abnormal human corneal epithelial surface: a scanning electron microscope study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:614–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, Zingirian M, Cancedda R, De Luca M. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet. 1997;349:990–993. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homma R, Yoshikawa H, Takeno M, Kurokawa MS, Masuda C, Takada E, et al. Induction of epithelial progenitors in vitro from mouse embryonic stem cells and application for reconstruction of damaged cornea in mice. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4320–4326. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Y, Peng H, Lavker RM. Emerging therapeutic strategies for limbal stem cell deficiency. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:7894647. doi: 10.1155/2018/7894647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F, Zhao SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells: potential role in corneal wound repair and transplantation. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6:296–304. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer-Blazejewska EA, Call MK, Yamanaka O, Liu H, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Kruse FE, et al. From hair to cornea: toward the therapeutic use of hair follicle-derived stem cells in the treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. Stem Cells. 2011;29:57–66. doi: 10.1002/stem.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu WL, Zhang JY, Fu X, Duan XN, Leung KKM, Jia ZQ, et al. Comparative study of the biological characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and peripheral blood of rats. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1793–1803. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satija NK, Singh VK, Verma YK, Gupta P, Sharma S, Afrin F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: a new paradigm in regenerative medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:4385–4402. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, Huang B. The multi-differentiation potential of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;3:48. doi: 10.1186/scrt139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph N, Prasad T, Raj V, Anil Kumar PR, Sreenivasan K, Kumary TV. A cytocompatible poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-glycidylmethacrylate) coated surface as new substrate for corneal tissue engineering. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2010;25:58–74. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madathil BK, Kumar PR, Kumary TV. N-Isopropylacrylamide-co-glycidylmethacrylate as a thermoresponsive substrate for corneal endothelial cell sheet engineering. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:450672. doi: 10.1155/2014/450672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sehic A, Utheim ØA, Ommundsen K, Utheim TP. Pre-clinical cell-based therapy for limbal stem cell deficiency. J Funct Biomater. 2015;6:863–888. doi: 10.3390/jfb6030863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venugopal B, Fernandez FB, Harikrishnan VS, John A. Post implantation fate of adipogenic induced mesenchymal stem cells on type I collagen scaffold in a rat model. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2017;28:28. doi: 10.1007/s10856-016-5838-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polymeri A, Giannobile WD, Kaigler D. Bone marrow stromal stem cells in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Horm Metab Res. 2016;48:700–713. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-118458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris DT. Stem cell banking for regenerative and personalized medicine. Biomedicines. 2014;2:50–79. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines2010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma S, Cabana R, Shariatmadar S, Krishan A. Cellular volume and marker expression in human peripheral blood apheresis stem cells. Cytometry A. 2008;73:160–167. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xian B, Zhang Y, Peng Y, Huang J, Li W, Wang W, et al. Adult human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are capable of producing neurocyte or photoreceptor-like cells that survive in mouse eyes after preinduction with neonatal retina. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:1515–1524. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pochampally R. Colony forming unit assays for MSCs. In: Prockop DJ, Bunnell BA, Phinney DG, editors. Mesenchymal stem cells. Totowa: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Digirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samsonraj RM, Rai B, Sathiyanathan P, Puan KJ, Rötzschke O, Hui JH, et al. Establishing criteria for human mesenchymal stem cell potency: establishing criteria for hMSC potency. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1878–1891. doi: 10.1002/stem.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu G, Liu P, Feng J, Jin Y. A novel population of mesenchymal progenitors with hematopoietic potential originated from CD14-peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8:16–29. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mijovic A, Pamphilon D. Harvesting, processing and inventory management of peripheral blood stem cells. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2007;1:16–23. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.28068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopper N, Wardale J, Brooks R, Power J, Rushton N, Henson F. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells enhance cartilage repair in in vivo osteochondral defect model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Via AG, Frizziero A, Oliva F. Biological properties of mesenchymal stem cells from different sources. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2:154–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidney LE, Branch MJ, Dunphy SE, Dua HS, Hopkinson A. Concise review: evidence for CD34 as a common marker for diverse progenitors: CD34 as a common marker for diverse progenitors. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1380–1389. doi: 10.1002/stem.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CS, Ning H, Lin G, Lue TF. Is CD34 truly a negative marker for mesenchymal stromal cells? Cytotherapy. 2012;14:1159–1163. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.729817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Angelis B, Gentile P, Orlandi F, Bocchini I, Di Pasquali C, Agovino A, et al. Limb rescue: a new autologous-peripheral blood mononuclear cells technology in critical limb ischemia and chronic ulcers. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21:423–435. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2014.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad S, Stewart R, Yung S, Kolli S, Armstrong L, Stojkovic M, et al. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into corneal epithelial-like cells by in vitro replication of the corneal epithelial stem cell niche. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1145–1155. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathews S, Prasad T, Venugopal B, Palakkan AA, Anil Kumar PR, Kumary TV. Standardizing transdifferentiation of rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to corneal lineage by simulating corneo-limbal cues. J Stem Cell Res Med. 2017 doi: 10.15761/JSCRM.1000119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaloin-Dufau C, Pavitt I, Delorme P, Dhouailly D. Identification of keratins 3 and 12 in corneal epithelium of vertebrates. Epithelial Cell Biol. 1993;2:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushnerev E, Shawcross SG, Sothirachagan S, Carley F, Brahma A, Yates JM, et al. Regeneration of corneal epithelium with dental pulp stem cells using a contact lens delivery system. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5192–5199. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li W, Chen YT, Hayashida Y, Blanco G, Kheirkah A, He H, et al. Down-regulation of Pax6 is associated with abnormal differentiation of corneal epithelial cells in severe ocular surface diseases. J Pathol. 2008;214:114–122. doi: 10.1002/path.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morita M, Fujita N, Takahashi A, Nam ER, Yui S, Chung CS, et al. Evaluation of ABCG2 and p63 expression in canine cornea and cultivated corneal epithelial cells. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015;18:59–68. doi: 10.1111/vop.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos T, Scott D, Ahmad S. An update on ocular surface epithelial stem cells: cornea and conjunctiva. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:601731. doi: 10.1155/2015/601731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dua HS, Saini JS, Azuara-Blanco A, Gupta P. Limbal stem cell deficiency: concept, aetiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000;48:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Secker GA, Daniels JT. Limbal epithelial stem cells of the cornea. In: StemBook [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard Stem Cell Institute; 2009. [PubMed]

- 41.Sasamoto Y, Ksander BR, Frank MH, Frank NY. Repairing the corneal epithelium using limbal stem cells or alternative cell-based therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:505–513. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1443442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsu CC, Peng CH, Hung KH, Lee YY, Lin TC, Jang SF, et al. Stem cell therapy for corneal regeneration medicine and contemporary nanomedicine for corneal disorders. Cell Transplant. 2015;24:1915–1930. doi: 10.3727/096368914X685744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narita T, Shintani Y, Ikebe C, Kaneko M, Campbell NG, Coppen SR, et al. The use of scaffold-free cell sheet technique to refine mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapy for heart failure. Mol Ther. 2013;21:860–867. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venugopal B, Shenoy SJ, Mohan S, Anil Kumar PR, Kumary TV. Bioengineered corneal epithelial cell sheet from mesenchymal stem cells—a functional alternative to limbal stem cells for ocular surface reconstruction. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2020;108:1033–1045. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Umemoto T, Yamato M, Nishida K, Okano T. Regenerative medicine of cornea by cell sheet engineering using temperature-responsive culture surfaces. Chin Sci Bull. 2013;58:4349–4356. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel NG, Zhang G. Responsive systems for cell sheet detachment. Organogenesis. 2013;9:93–100. doi: 10.4161/org.25149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: PBMNC colonies stained with crystal violet. (A) Colonies with less than 50, considered small colonies (B) Colonies with cells between 50 and 100, considered as medium sized colonies (C) Colonies with more than 100 cells, considered as large colonies (TIF 960 kb)