Abstract

Background and Purpose

Corticosteroid resistance poses a major barrier to an effective anti‐inflammatory therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The present study aimed to investigate potential corticosteroid re‐sensitization actions of andrographolide, a bioactive molecule from the herb Andrographis paniculata, in COPD models, particularly in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from COPD patients.

Experimental Approach

Corticosteroid sensitivity in PBMCs collected from COPD patients, or in human monocytic U937 cells exposed to cigarette smoke extract (CSE), was determined by measuring LPS‐induced IL‐8 production, in the presence and absence of andrographolide. The mechanisms of corticosteroid re‐sensitization action of andrographolide were evaluated in a mouse cigarette smoke (CS)‐induced acute lung injury model.

Key Results

Impaired inhibition of IL‐8 production by dexamethasone was detected in PBMCs from COPD patients and in CSE‐exposed U937 cells, together with reduced levels of nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2 (Nrf2) and histone deacetylase‐2 (HDAC2). In both PBMCs and CSE‐exposed U937 cells, andrographolide restored dexamethasone inhibition of IL‐8 production, accompanied by the up‐regulation of Nrf2 and HDAC2 levels. In the U937 cells, andrographolide was able to block CSE‐induced Akt and reduce the level of c‐Jun. Besides, andrographolide also augmented dexamethasone actions on lowering total and neutrophil counts, cytokine levels, and oxidative damage markers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from CS‐exposed mice.

Conclusion and Implications

We report here for the first time a novel corticosteroid re‐sensitization property of andrographolide in human PBMCs and provide mechanistic evidence to support clinical evaluation of andrographolide in reversing steroid resistance in COPD.

Abbreviations

- AP‐1

activator protein 1

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

cigarette smoke

- CSE

cigarette smoke extract

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- HAT

acetyltransferase

- HDAC2

histone deacetylase‐2

- LABA

long‐acting β2 agonist

- LAMA

long‐acting muscarinic antagonist

- 3‐NT

3‐nitrotyrosine

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TBP

TATA‐box binding protein

What is already known

COPD is generally corticosteroid‐insensitive, probably due to a reduction of cellular Nrf2 or HDAC2 level.

Restoration of cellular Nrf2 or HDAC2 level helps regain corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD.

What this study adds

Andrographolide, a labdane diterpenoid bioactive molecule, could reverse corticosteroid resistance in COPD models.

Andrographolide acts by inhibiting PI3K/Akt pathway and restoring Nrf2 and HDAC2 levels in COPD models.

What is the clinical significance

Andrographolide may be a novel compound for corticosteroid re‐sensitization in COPD treatment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), manifested with lung inflammation, alveolar wall destruction, and irreversible airway obstruction, is projected to become the third leading cause of death by 2020 (May & Li, 2015). Exposure to tobacco smoke remains the single most important risk factor for the development of COPD. It is driven by T helper cell type 1 (Th1) and type 17 (Th17), and CD8+ cytotoxic T cell (Tc1) immune responses with elevated IL‐1β, IL‐17A, TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐8 levels with predominant neutrophil and CD8 lymphocyte infiltration into the lung (Barnes, 2016). Currently, there is no effective treatment for COPD that can halt the disease progression. Roflumilast, a PDE 4‐selective inhibitor, confers very limited therapeutic benefit to COPD with dose‐limiting major side effects (Wedzicha, Calverley, & Rabe, 2016). Combined inhaled long‐acting β2 agonist (LABA) and long‐acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) is currently the mainstay therapy for stable COPD, which could relieve disease symptoms but do not significantly influence the underlying disease progression (Montuschi & Ciabattoni, 2015). In contrast to asthma that can be well‐controlled by inhaled corticosteroids, the clinical symptoms and inflammatory response in COPD patients are notably unresponsive to the anti‐inflammatory benefits of corticosteroids, even at high inhaled or oral doses (Barnes, 2013). A number of reports have shown that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from COPD patients are corticosteroid‐insensitive, making PBMCs a good in vitro model to study corticosteroid resistance (Mitani, Ito, Vuppusetty, Barnes, & Mercado, 2016; To et al., 2010). Besides, cigarette smoke (CS) exposure to mice induced marked influx of neutrophils and elevation of KC and IL‐6 levels in the airway, which were refractory to corticosteroid treatment, making CS‐induced lung injury model a suitable tool to investigate corticosteroid resistance in vivo (Marwick et al., 2009; To et al., 2010).

Corticosteroids act by binding to their cognate glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and forming homodimers, which are then translocated into the nucleus to modulate target gene expression mediated by transcription factors such as NF‐κB and activator protein 1 (AP‐1; Oakley & Cidlowski, 2013). It is the recruitment of transcription corepressor histone deacetylase‐2 (HDAC2) by the GR homodimers that inhibits the NF‐κB‐histone acetyltransferase (HAT) transcriptome activator complex to achieve optimum anti‐inflammatory effects by corticosteroids (Barnes, 2009b). A number of molecular mechanisms have been identified to contribute to corticosteroid resistance in COPD (Barnes, 2013; Jiang & Zhu, 2016). Decreased GR nuclear translocation as a result of receptor phosphorylation at Ser226 by p38 MAPK (MAPK) can induce steroid resistance (Mercado et al., 2012). Reduced level or impaired activity of HDAC2 or of the antioxidative transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2 (Nrf2) can also confer steroid insensitivity (Barnes, 2009a). It has been shown that CS‐heightened oxidative stress leads to activation of the phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway to phosphorylate HDAC2, resulting in its inactivation and degradation (To et al., 2010). Excessive accumulation of AP‐1, a heterodimer of c‐Fos and c‐Jun, has been shown as a mechanism of corticosteroid resistance due to its physical interaction with GRs, preventing GRs from executing its anti‐inflammatory action (Barnes, 2010). Therefore, agents that can restore HDAC2 or Nrf2 level, inhibit PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, or reduce AP‐1 level may be effective in promoting corticosteroid anti‐inflammatory activities (Al‐Harbi et al., 2019; Mitani et al., 2016; Mitani et al., 2017).

Andrographolide, a labdane diterpene lactone bioactive molecule isolated from the plant Andrographis paniculata, has long been used as natural remedy for the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract infection in Asian countries and in Scandinavia (Tan, Liao, Zhou, & Wong, 2017). We have previously demonstrated the protective effects of andrographolide in experimental COPD and COPD exacerbation models (Guan et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2016). More recently, we have reported the corticosteroid re‐sensitization capability of andrographolide in an experimental LPS/IFN‐γ‐induced severe asthma model (Liao, Tan, & Wong, 2016).

In this study, we investigated if andrographolide could restore corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD and explored the potential mechanisms involved in andrographolide‐mediated steroid re‐sensitization. Our findings revealed for the first time that andrographolide was able to restore corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD, and it accompanied by the restoration of HDAC2 and Nrf2 levels in COPD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Human subjects

Human subjects were recruited to the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine of the Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore. The human study was approved by the Institutional Domain‐Specific Review Board (DSRB) of the Tan Tock Seng Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Twelve healthy subjects (HS) and 11 COPD patients were successfully recruited for the study, and their profiles are summarized in Table 1. COPD patients were staged based on the GOLD criteria. Lung function spirometry was performed in all COPD patients according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines. None of the COPD patients was treated with systemic corticosteroids. PBMCs were isolated using Lymphoprep and SepMate‐50 (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada).

TABLE 1.

The profile of HS and patients with COPD

| Profile | HS (n = 12) | COPD (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, years) | 30.0 (25.5–48.5) | 67.0 (62.0–71.0) * |

| Sex (M/F) | 8/4 | 11/0 |

| FVC (median, % predicted) | 107 (91–114) | 73.0 (66.0–92.0) * |

| FEV1 (median, % predicted) | 99.5 (90–107) | 47.0 (35.0–66.0) * |

| GOLD stage (1/2/3/4) | ‐ | 0/5/5/1 |

| Smoking (current/ex) | ‐ | 7/4 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HS, healthy subjects.

P < 0.05 compared with HS.

2.2. In vitro corticosteroid sensitivity assays

PBMCs were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in 96‐well plates. After 4‐h incubation with andrographolide (1 μM) or 0.01% DMSO as a vehicle control, cells were treated with increasing concentrations (10−10 to 10−5 M) of dexamethasone 21‐phosphate disodium (≥98%) for 1 h before overnight stimulation with 1 ng˙ml−1 LPS. Human monocytic U937 cells (ATCC Cat# CRL‐1593.2, RRID:CVCL_0007) were maintained in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS but starved with 1% FBS overnight before treatment. In the preliminary study, we found that higher concentrations of andrographolide were needed to be effective in U937 cells than in PBMCs. U937 cells were pretreated with andrographolide (10, 20, and 30 μM) or 0.05% DMSO as vehicle control for 30 min and then incubated with 2% cigarette smoke extract (CSE; Tan et al., 2016) for another 4 h. Cells were then stimulated with 100 ng˙ml−1 LPS overnight in the presence or absence of dexamethasone (10−10 to 10−5 M). Supernatants were collected, and IL‐8 level was measured by elisa (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Corticosteroid sensitivity is presented as the dexamethasone concentrations required to inhibit 30% of LPS‐induced IL‐8 production in PBMCs (Dex‐IC30).

2.3. Animals

Female BALB/c mice of 6 to 8 weeks old (20–25 g) were purchased from the InVivos Pte Ltd (Singapore) and maintained in a 12‐h light–dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. A euthanasia protocol based on an intraperitoneal injection of an anaesthetic mixture of ketamine and medetomidine was used at the end of the animal study to minimize pain and distress. Animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the International Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the National University of Singapore (Animal protocol number: R14‐0347). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny, Browne, Cuthill, Emerson, & Altman, 2010; McGrath & Lilley, 2015) and with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology.

2.4. CS‐induced acute lung injury mouse model and treatment protocol

Mice were randomly divided into six groups of eight mice per group (Figure 4b). The sample size was determined based on our previous study (Peh et al., 2017). Mice were placed in a ventilated chamber filled with 4% CS delivered using peristaltic pumps (Masterflex, Cole‐Parmer Instrument Co., Niles, IL) at a constant rate of 1 L˙min−1 as described (Guan et al., 2013). Mice were exposed to three sticks of 3R4F research cigarettes thrice per day for 2 weeks (five consecutive days per week) to induce lung injury (Peh et al., 2017). Mice in the sham air group were simultaneously placed in another ventilated chamber but exposed to fresh air. Dexamethasone 21‐phosphate disodium (1 mg˙kg−1), andrographolide (0.3 mg˙kg−1 in DMSO), or vehicle control (2% DMSO) in 0.1‐ml PBS was given 2 h before CS exposure in the second week via intraperitoneal injection. Mice were killed 24 h after the last CS or sham air exposure, and lung samples were collected for analysis.

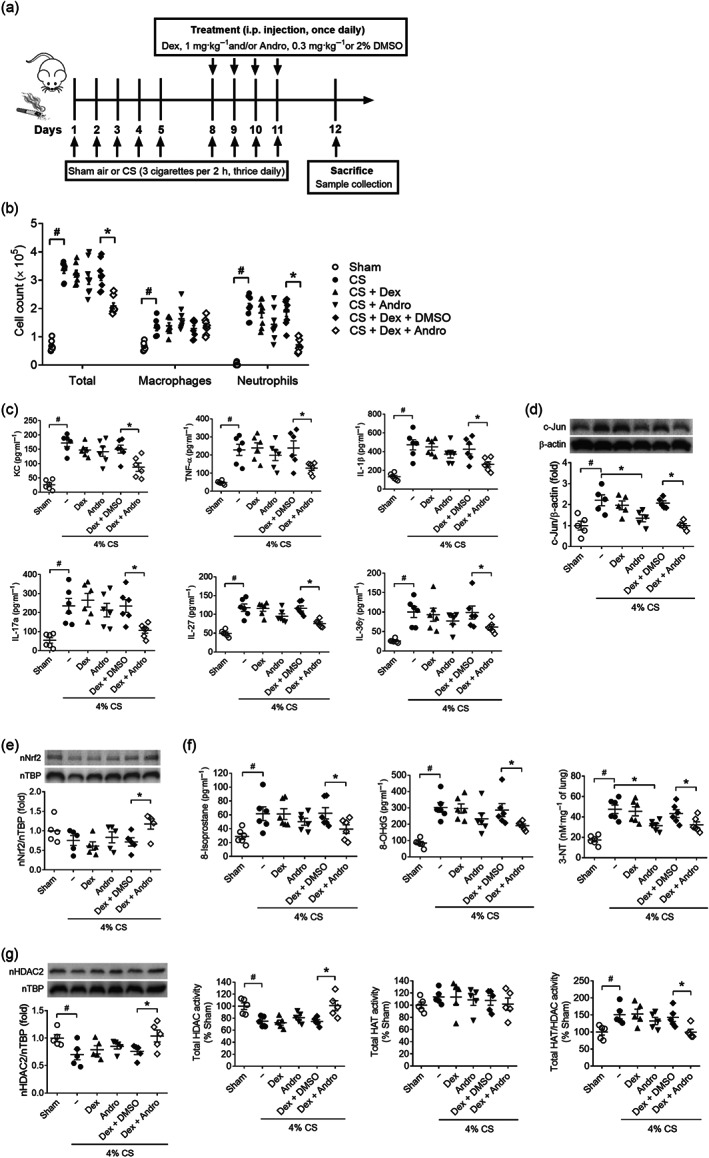

FIGURE 4.

Restoration of corticosteroid sensitivity in cigarette smoke‐induced airway inflammation in vivo. (a) A schematic diagram of 2‐week cigarette smoke (CS)‐induced acute lung injury model and treatment protocol. (b) Total and differential cell count in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid obtained from CS‐exposed mice after Andro and/or Dex treatment (n = 8). (c) BAL fluid cytokine and chemokine levels measured by sandwich elisa (n = 6). (d) Immunoblot of c‐Jun protein level in mouse lung mononuclear cells (n = 5). (e) Immunoblot of nuclear Nrf2 protein levels in mouse lung mononuclear cells (n = 5). (f) Oxidative damage markers 8‐isoprostane and 8‐OHdG measured in mouse BAL fluid and 3‐nitrotyrosine (3‐NT) assayed in mouse lung tissue homogenate (n = 6). (g) Immunoblot of nuclear HDAC2 protein levels in mouse lung mononuclear cells and total HDAC and HAT activity in mouse lung nuclear homogenate (n = 5). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. # P < 0.05 compared with sham control and *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control DMSO by nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test

2.5. BAL fluid and lung tissues

Tracheotomy was performed, and a cannula was inserted into the mouse trachea. Ice‐cold PBS (0.5 ml × 3) was instilled into the lungs, and BAL fluid was collected. BAL fluid total and differential cell counts (Figure 4b) were determined as described in a blinded manner (Bao et al., 2009; Peh et al., 2017). BAL fluid supernatants were analysed for cytokines including TNF‐α (BD Biosciences), IL‐1β (BD Biosciences), IL‐17A (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), IL‐27 p28 (R&D Systems, Inc.), KC (R&D Systems, Inc.) and IL‐36γ (MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA), and oxidative damage markers 8‐isoprostane and 8‐OHdG (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), using sandwich elisa. Mouse lungs were excised, snap‐frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored in −80°C for subsequent analysis.

2.6. Mouse lung mononuclear cell preparation

Five mice per treatment group were used to prepare mouse lung mononuclear cells. For this experiment, mouse whole lung was perfused with 5‐ml PBS and minced into 2‐ to 3‐mm pieces. Full RPMI‐1640 medium containing collagenase type I (2 mg˙ml−1) and DNase I (100 U˙ml−1) was used to digest lungs into single cell suspension. Lung mononuclear cells were harvested using Percoll™ density gradient (40% over 80%) centrifugation by collecting the mononuclear cells from the interphase. These primary cells were pelleted and stored in −80°C for further analysis.

2.7. RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAzol according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNAs were synthesized using qScript™ cDNA SuperMix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA). cDNA synthesis was performed by the Biometra gradient thermal cycler (Goettingen, Germany). qPCR was performed with SYBR Green qPCR MasterMix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a detection dye in the ABI 7900 Real‐Time PCR machine and presented as fold differences over the controls by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The efficiency of all used primer pairs was pretested. The fold change of mRNA level was adjusted to the efficiency of primer pairs used. Human β‐actin gene ACTB was used as an endogenous control. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The primer pairs are listed as following: human ACTB: forward 5′‐CAT GTA CGT TGC TAT CCA GGC‐3′, reverse 5′‐ CTC CTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT‐3′; human HMOX1: forward 5′‐ AAG ACT GCG TTC CTG CTC AAC‐3′, reverse 5′‐AAA GCC CTA CAG CAA CTG TCG‐3′; human NQO1: forward 5′‐GAA GAG CAC TGA TCG TAC TGG C‐3′, reverse 5′‐GGA TAC TGA AAG TTC GCA GGG‐3′.

2.8. Total lysate, nuclear fractionation, and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in M‐PER® Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent containing Pierce™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein were extracted from cells or mouse lung tissues using Nuclear Extraction Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Protein extracts were separated by 10% SDS‐PAGE or 4–15% Mini‐PROTEAN® TGX™ precast protein gels (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, RRID:SCR_008426), transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with antibodies. Immunoblots were visualized and documented with ChemiDoc™ Touch Gel Imaging System (Bio‐Rad Laboratories). Band intensity was quantitated using ImageJ software (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070). The immuno‐related procedures used comply with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2018). Anti‐β‐actin (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3700, RRID:AB_2242334), anti‐HDAC2 (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2545, RRID:AB_2116819), anti‐Akt (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 4685, RRID:AB_2225340), anti‐phospho‐Akt (Ser473; Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 4060, RRID:AB_2315049), anti‐p70S6K (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2708, RRID:AB_390722), anti‐phospho‐p70S6K (Ser389; Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 9234, RRID:AB_2269803), anti‐c‐Jun (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 9165, RRID:AB_2130165), anti‐TATA box binding protein (TBP; Abcam Cat# ab51841, RRID:AB_945758), anti‐p‐HDAC2 (Abcam Cat# ab75602, RRID:AB_1310303), and anti‐Nrf2 (Abcam Cat# ab62352, RRID:AB_944418) antibodies were used for immunoblotting.

2.9. Immunoprecipitation of HDAC2

Total U937 cell lysates were prepared by using 200 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Triton X‐100, 0.5% CHAPS, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor. Cell lysates were pre‐cleared with 20‐μl Dynabeads™ Protein G for 30 min. After removal of the beads with DynaMag™‐Spin Magnet (Thermo Fisher Scientific), the cell lysates were further incubated with 2‐μg anti‐HDAC2 (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2545, RRID:AB_2116819) or anti‐rabbit lgG (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2729, RRID:AB_1031062) antibodies, together with another 30‐μl Dynabeads™ Protein G overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. The immune complexes were pelleted with DynaMag™‐Spin Magnet, washed twice with 1 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer, and divided equally after the final wash for the HDAC2 activity assay and immunoblotting.

2.10. HAT and HDAC activity assays

Nuclear lysates were extracted from U937 cells or mouse lung tissues (Active Motif). FLUOR DE LYS® HDAC fluorometric and HAT colorimetric activity assay kits were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY). Total HAT activity and HDAC activity were assayed according to the manufacturer's instructions, respectively. HDAC2‐specific activity assay was performed using immune complex pulled down by anti‐HDAC2 antibody. The raw data were normalized to the medium or sham air control. Total HAT/HDAC activity ratio was calculated using the normalized values.

2.11. Data and statistical analysis

Graphs and statistical analyses were made with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism, RRID:SCR_002798) version 8.0. All Dex‐IC30 values were calculated using nonlinear regression and sigmoidal inhibition‐response curve fit by GraphPad Prism and presented as log‐transformed values (Figures 1b and 5a). Corticosteroid sensitivity was presented as percentage of inhibition of IL‐8 in response to log‐transformed dexamethasone concentration (Figures 2b and 3a). Some results such as RT‐PCR data were normalized to control to avoid unwanted sources of variation. Outliers were included in all data analyses. Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare the statistical difference between two unpaired treatment groups. Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed rank test was used to compare the statistical difference between two paired treatment groups. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test was used for comparison between multiple treatment groups. P values below 0.05 were considered to be significant. The data shown are expressed as means ± SEM. Analysis of significance was performed only for group size or independent value with n ≥ 5. Due to limited remaining COPD PBMC protein lysate samples, we only included n = 2 data for Nrf2 immunoblot analysis (Figure 5c). The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018).

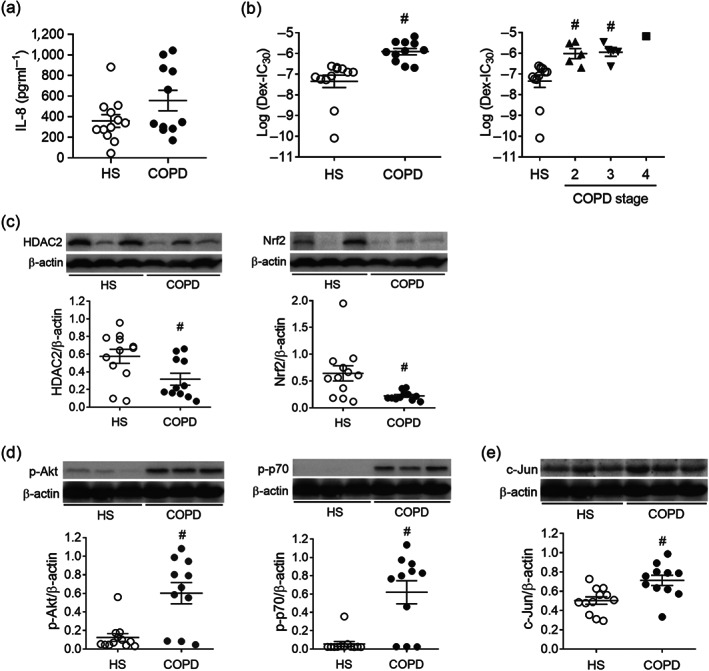

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy subjects (HS) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. (a) IL‐8 production by PBMCs upon LPS stimulation overnight. IL‐8 production in supernatant was measured by elisa. (b) Corticosteroid sensitivity was evaluated as the concentration of dexamethasone (Dex) required to inhibit 30% of LPS‐induced IL‐8 production (Dex‐IC30). PBMCs were plated in the presence and absence of various concentrations of Dex for 1 h before overnight stimulation with 1 ng˙ml−1 LPS. IL‐8 production in supernatant was measured by elisa. (c) Nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2 (Nrf2) and histone deacetylase‐2 (HDAC2) protein levels from the total lysates of PBMCs were detected by immunoblotting. (d) PI3K pathway activity in PBMCs was measured as phosphorylated Akt (p‐Akt) and p70S6K (p‐p70S6K) by immunoblotting. (e) Transcription factor activator protein‐1 (AP‐1) subunit c‐Jun level in PBMCs were evaluated by immunoblotting. (n = 12 for HS; n = 11 for COPD). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. # P < 0.05 compared with HS by nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test

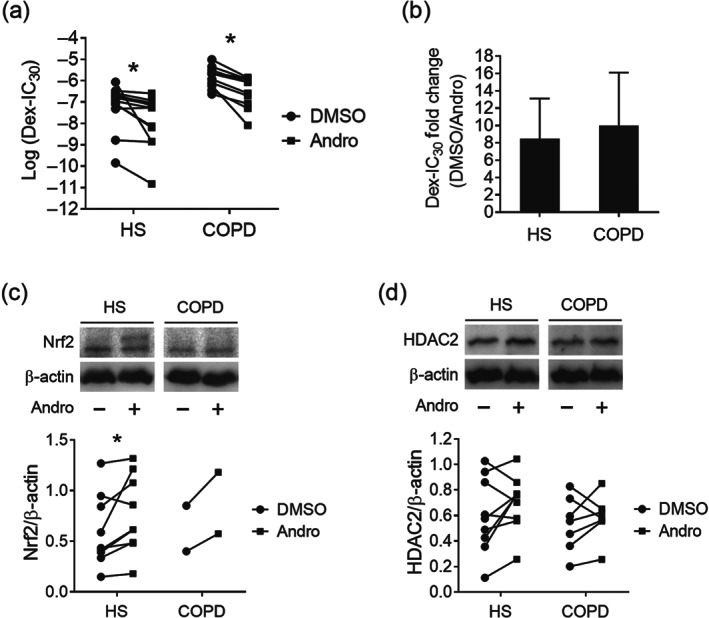

FIGURE 5.

Improvement of corticosteroid sensitivity in PBMCs by andrographolide. (a) Corticosteroid sensitivity was evaluated as the concentration of Dex required to inhibit 30% of LPS‐induced IL‐8 production (Dex‐IC30). PBMCs were pretreated with Andro or DMSO for 4 h, followed by Dex for 1 h before overnight stimulation with 1 ng˙ml−1 LPS. IL‐8 production in supernatant was measured by elisa (n = 12 for HS; n = 11 for COPD). (b) Fold change of Dex‐IC30 value upon Andro treatment in PBMCs from both HS and COPD groups (n = 12 for HS; n = 11 for COPD). (c) Immunoblot of Nrf2 level in PBMCs after Andro treatment (n = 9 for HS; n = 2 for COPD). (d) Immunoblot of HDAC2 level in PBMCs after Andro treatment (n = 9 for HS; n = 7 for COPD). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control DMSO by nonparametric Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed rank test

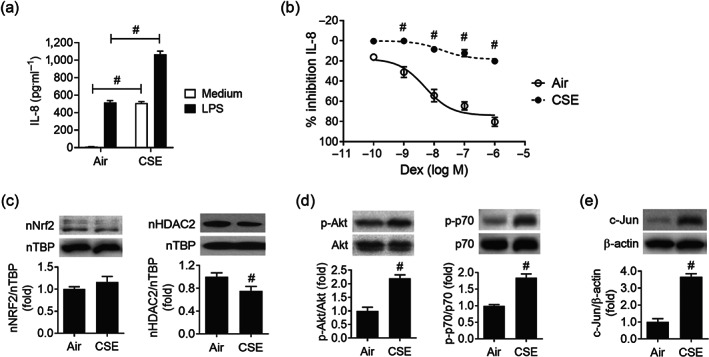

FIGURE 2.

Induction of corticosteroid resistance in human monocytic cell line U937 upon cigarette smoke extract exposure. (a) Cigarette smoke extract (CSE, 2%) exposure augmented LPS‐stimulated IL‐8 production in U937 cells. (b) Corticosteroid sensitivity was calculated as the percentage of inhibition of LPS‐stimulated IL‐8 production by Dex. U937 cells were exposed to 2% CSE for 4 hours, followed by treatment of various concentrations of Dex for 1 h before overnight stimulation with 100 ng˙ml−1 LPS. IL‐8 production in supernatant was measured by elisa (n = 6). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. # P < 0.05 compared with air control by unpaired Student t test. (c) Immunoblots of nuclear Nrf‐2 and HDAC2 protein levels upon 2% CSE exposure (n = 6). (d) CSE‐induced PI3K pathway activity was reflected by downstream Akt (n = 6) and p70S6K (n = 5) phosphorylation by immunoblotting. (e) AP‐1/c‐Jun (n = 6) level was evaluated by immunoblotting after CSE exposure. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. # P < 0.05 compared with HS by nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test

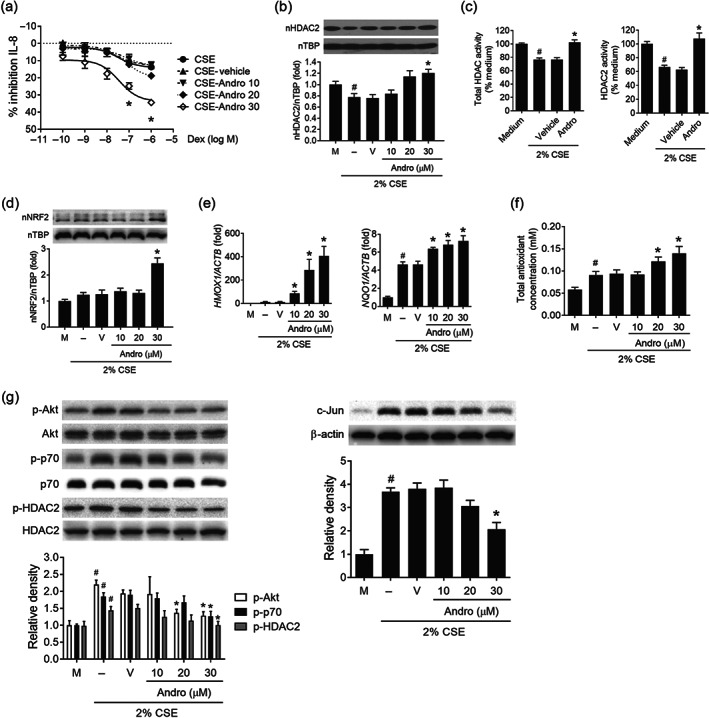

FIGURE 3.

Re‐sensitization of corticosteroid resistance by andrographolide in U937 cells. (a) Corticosteroid sensitivity was calculated as the percentage of inhibition of LPS‐stimulated IL‐8 production by Dex. U937 cells were pretreated with andrographolide (Andro) or vehicle control (0.05% DMSO) for 30 min before exposure to CSE for another 4 h. Cells were then stimulated with 100 ng˙ml−1 LPS overnight in the presence or absence of Dex. IL‐8 production in supernatant was measured by elisa (n = 6). (b) Immunoblot of nuclear HDAC2 level upon CSE exposure in response to various concentrations of Andro (n = 6). (c) Effects of Andro (30 μM) on total HDAC and HDAC2‐specific activity upon CSE exposure (n = 5). (d) Immunoblot of nuclear Nrf2 level upon CSE exposure in response to various concentrations of Andro (n = 6). (e) Effects of Andro on mRNA expression of Nrf2‐regulated genes upon CSE exposure (n = 5). (f) Effect of Andro on total antioxidant capacity in CSE‐exposed U937 cells (n = 6). (g) Immunoblots of p‐Akt (n = 6), p‐p70S6K (n = 5), p‐HDAC2 (n = 5), and c‐Jun (n = 6) levels by various concentrations of Andro in CSE‐exposed U937 cells. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. # P < 0.05 compared with medium control, and *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control by nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test

2.12. Materials

Dexamethasone 21‐phosphate disodium salt (98%), andrographolide (98%), DMSO (99% cell culture grade), LPS [0111: B4], RNAzol, and Percoll™ reagent were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Lymphoprep was purchased from STEMCELL Technologies (Vancouver, Canada). Collagenase type I, DNase I, Dynabeads™ Protein G, M‐PER® Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent, and Pierce™ Protease and Phosphoatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets came from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). 3R4F research cigarettes were purchased from Tobacco and Health Research Institute, University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY).

2.13. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 (Alexander et al., 2019; Alexander et al., 2019).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Corticosteroid insensitivity in PBMCs from patients with COPD

PBMCs were isolated from blood samples collected from non‐smoking HS and COPD patients. Figure 1a showed the absolute levels of LPS‐induced IL‐8 production by PBMCs from HS and COPD patients. Corticosteroid sensitivity was indicated as the dexamethasone concentration required to inhibit 30% of LPS‐induced IL‐8 production (Dex‐IC30) in PBMCs. The log (Dex‐IC30) values obtained from COPD PBMCs were significantly higher than those from HS (−7.35 ± 0.30 vs. −5.91 ± 0.15), implicating that PBMCs from COPD patients were on average 27‐fold less sensitive to dexamethasone (Figure 1b). There was also a trend of increased corticosteroid insensitivity levels with clinically diagnosed COPD (Figure 1b).

The protein levels of the transcription corepressor HDAC2 and the antioxidative transcription factor Nrf2 were down‐regulated in the total lysates of PBMCs from COPD patients (Figure 1c). Besides, the PI3K/Akt pathway was activated in COPD, with markedly elevated Akt and p70S6K phosphorylation detected in the COPD PBMCs (Figure 1d). In addition, transcription factor AP‐1 subunit c‐Jun accumulation was identified in the PBMCs from COPD patients (Figure 1e). These data provide potential molecular mechanisms responsible for corticosteroid insensitivity in COPD.

3.2. Induction of corticosteroid resistance upon CS extract exposure in vitro

To recapitulate the corticosteroid resistance feature of PBMCs from COPD patients, a human monocytic cell line U937 was exposed to 2% CSE for 4 h before corticosteroid sensitivity was assessed (Mitani et al., 2016; To et al., 2010). CSE exposure alone increased IL‐8 release, but CSE markedly augmented LPS‐induced IL‐8 production in U937 cells (Figure 2a). In CSE‐exposed U937 cells, dexamethasone failed to block LPS‐induced IL‐8 production (Figure 2b). We also observed that in these CSE‐exposed U937 cells, the nuclear HDAC2 level was reduced, a similar finding observed in COPD PBMCs (Figure 2c). In contrast to a drastic drop in Nrf2 level in PBMCs from COPD patients with chronic CS exposure, there was no significant change in nuclear Nrf2 level in U937 cells upon acute CSE exposure, implying an active process such as endogenous antioxidative mechanism counteracting the acute oxidative stress (Figure 2c). In line with the COPD PBMCs, phosphorylation of Akt and p70S6K (Figure 2d) and accumulation of c‐Jun (Figure 2e) were recapitulated in CSE‐exposed U937 cells.

3.3. Mechanisms of andrographolide in restoring corticosteroid sensitivity in vitro

At 30 μM, andrographolide significantly restored the anti‐inflammatory actions of dexamethasone on LPS‐induced IL‐8 production in CSE‐exposed U937 cells (Figure 3a). Andrographolide was able to enhance nuclear HDAC2 level and HDAC2 activity in U937 cells pre‐exposed to CSE (Figure 3b,c). In addition, andrographolide was found to increase nuclear Nrf2 level (Figure 3d), gene expression of Nrf2‐regulated genes: haem oxygenase (HMOX)‐1 and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) (Figure 3e), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC; Figure 3f), in CSE‐exposed U937 cells. Furthermore, andrographolide significantly inhibited phospho‐Akt/phospho‐p70S6K/phospho‐HDAC2 and c‐Jun accumulation in a concentration‐dependent manner in U937 cells exposed to CSE (Figure 3g).

3.4. Andrographolide restores corticosteroid sensitivity in CS‐induced airway inflammation in vivo

BALB/c mice were exposed to 4% CS for 2 weeks to induce lung injury (Peh et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2016), and dexamethasone (1 mg˙kg−1) was given with and without andrographolide (0.3 mg˙kg−1) once daily in the second week of CS inhalation (Figure 4a). CS markedly increased bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid levels of inflammatory cells, mainly alveolar macrophages and neutrophils. Dexamethasone and andrographolide when given alone failed to block CS‐induced inflammatory cell infiltration, whereas dexamethasone in combination with andrographolide significantly blocked BAL fluid neutrophil counts (Figure 4b). In a similar manner, andrographolide facilitated dexamethasone inhibition of CS‐induced increases in BAL fluid levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines including KC, TNF‐α, IL‐17A, IL‐1β, IL‐27, and IL‐36γ (Figure 4c).

In line with the findings from U937 cells and COPD PBMCs, CS markedly increased c‐Jun protein levels in primary mononuclear cells isolated from mouse lung. Dexamethasone alone did not alter CS‐induced c‐Jun protein accumulation (Figure 4d). In combination with andrographolide, dexamethasone was able to significantly reduce c‐Jun levels in the lung mononuclear cells (Figure 4d). Two‐week CS inhalation moderately depleted nuclear Nrf2 level in mouse lung mononuclear cells. Dexamethasone alone failed to restore the Nrf2 level, whereas combined andrographolide and dexamethasone significantly raised nuclear Nrf2 protein accumulation (Figure 4e). Andrographolide has been shown to be a potent Nrf2 activator (Smirnova et al., 2011) and is anticipated to increase HDAC2 stability and facilitate corticosteroid actions. In consequence, dexamethasone in the presence of andrographolide markedly suppressed the levels of oxidative damage markers such as 8‐isoprostane and 8‐OHdG in BAL fluid and 3‐nitrotyrosine (3‐NT) in lung tissue from CS‐challenged mice (Figure 4f). In addition, dexamethasone in combination with andrographolide completely restored CS depletion of nuclear HDAC2 in isolated lung mononuclear cells and promoted total HDAC activities in CS‐challenged lungs (Figure 4g). Acetylation of histones by the transcriptional coactivator histone acetyltransferase (HAT) leads to chromatin opening for inflammatory gene transcription. In CS‐exposed lungs, total HAT and total HAT/HDAC activity ratios were elevated. While combined dexamethasone and andrographolide had no direct effects on CS‐induced HAT activity, they significantly reduced the total HAT/HDAC activity ratio, contributing to its corticosteroid re‐sensitization capability in vivo (Figure 4g).

3.5. Restoration of corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD PBMCs by andrographolide

Pretreatment of COPD PBMCs with andrographolide restored dexamethasone anti‐inflammatory effects on LPS‐induced IL‐8 production with a significant decrease in log (Dex‐IC30) value from −5.84 ± 0.15 to −6.50 ± 0.22 (Figure 5a). Andrographolide also facilitated dexamethasone anti‐inflammatory actions in PBMCs from healthy subjects. Overall, andrographolide promoted corticosteroid sensitivity by 8.5 ± 4.6‐fold in healthy subjects and 10.0 ± 6.1‐fold in COPD (Figure 5b).

With limited remaining PBMC samples and very low expression levels of Nrf2 in COPD PBMCs (Figure 1c), total Nrf2 lysate levels were detectable in only two of the COPD samples (one stage 2 and one stage 3), and their levels were slightly up‐regulated by andrographolide (Figure 5c, preliminary data). Andrographolide was found to significantly enhance Nrf2 levels in PBMCs from HS. Likewise, an overall trend of augmented HDAC2 levels upon andrographolide treatment was seen in the PBMCs from both HS and COPD patients, though statistical significance was not achieved (Figure 5d).

4. DISCUSSION

Exposure to tobacco smoke remains the single most important risk factor for COPD. Corticosteroid resistance is a challenging problem in COPD treatment. CS‐induced oxidative stress plays a critical role in the development of corticosteroid resistance in severe asthma and COPD (Barnes, 2013). In this study, we have explored the role of monocytes/macrophages in corticosteroid insensitivity using COPD PBMCs, CSE‐exposed human U937 monocytic cells, and CS‐induced acute lung injury model and confirmed the effectiveness of andrographolide in regaining corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD accompanied by restoration of the Nrf2 and HDAC2 levels in mononuclear cells. This is the first report to show corticosteroid re‐sensitizing capability of andrographolide in modulating Nrf2 and HDAC2 in the context of COPD.

Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is considered a contributing mechanism to corticosteroid insensitivity in COPD, which is supposed to induce HDAC2 phosphorylation, activity impairment, and protein degradation (To et al., 2010). Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway has been shown to restore corticosteroid sensitivity in steroid‐resistant experimental models and in PBMCs from COPD patients through restoration of the HDAC2 level and activity (To et al., 2010). In this study, we observed increases in Akt and p70S6K phosphorylation in PBMCs from COPD patients and CSE‐exposed U937 cells. In U937 cells, CSE could enhance phosphorylation of HDAC2. In consequence, HDAC2 level and activity were found down‐regulated in PBMCs from COPD patients, CSE‐exposed U937 cells, and CS‐exposed mouse lungs. Andrographolide blocked CSE‐induced Akt, p70S6K, and HDAC2 phosphorylation in the U937 cells and was found to recover HDAC2 level and enhance HDAC2 activity in COPD samples and in CS‐exposed in vitro and in vivo models. As a result, andrographolide enabled dexamethasone to regain its inhibitory actions against LPS‐induced IL‐8 production in CSE‐exposed U937 cells and against CS‐induced lung neutrophil infiltration and pro‐inflammatory cytokine production including IL‐17A, IL‐1β, IL‐27, and IL‐36γ.

Nrf2, a potent antioxidant transcription factor that regulates a wide array of antioxidant genes, can minimize degradation of HDAC2 by reducing oxidative and nitrosative stress and restoring HDAC2 level and activity (Adenuga et al., 2010; Mercado et al., 2011). A recent report shows that activation of Nrf2 by sulforaphone reversed corticosteroid resistance in a mixed granulocytic mouse model of asthma by up‐regulating endogenous antioxidants and attenuating Th17 immune responses in airways (Al‐Harbi et al., 2019). Andrographolide has been reported to be the most robust Nrf2 activator from a spectrum library of 2,000 biologically active compounds using a Neh2‐luciferase reporter gene assay (Smirnova et al., 2011). In this study, andrographolide has demonstrated its potent Nrf2 activator function in CSE‐induced U937 cells and in PBMCs from COPD patients in vitro, and in a CS‐exposed lung injury model in vivo, by increasing Nrf2 nuclear accumulation, up‐regulating antioxidant gene (e.g., HMOX1 and NQO1) expression, leading to enhanced total antioxidant capacity in vitro and reduced oxidative damage markers in vivo. Our findings implicate that andrographolide can also execute its corticosteroid re‐sensitization effect via Nrf2 pathway to restore HDAC2 levels in COPD.

AP‐1 is a well‐characterized pro‐inflammatory transcription factor, regulating a variety of inflammatory mediators together with NF‐κB (Fujioka et al., 2004). CS exposure has been shown to up‐regulate AP‐1 activity in three‐dimensional human bronchial epithelial cells and in mouse lungs (Sekine et al., 2019). Increased c‐Fos and c‐Jun expression levels were reported in the PBMCs and lung tissues from severe asthmatics and COPD patients, implicating the potential role of AP‐1 in corticosteroid resistance (Adcock, Lane, Brown, Lee, & Barnes, 1995; Mitani et al., 2016). In the present study, elevated c‐Jun levels were observed in PBMCs from COPD patients, CSE‐exposed U937 cells, and CS‐exposed mouse lung tissues. We observed that andrographolide not only suppressed CSE‐stimulated JNK phosphorylation and c‐Jun expression in U937 cells but also decreased CS‐induced c‐Jun protein level in mouse lung, which may be partly responsible for restoring the anti‐inflammatory actions of dexamethasone in CS‐induced lung injury model.

Andrographolide is a naturally occurring labdane diterpenoid with known anti‐inflammatory activities. It possesses an inhibitory α,β‐unsaturated lactone to form a Michael acceptor system, which is an electrophilic structure that can covalently react with nucleophilic thiol groups in target proteins (Tran, Wong, & Chai, 2017). Andrographolide has been shown to form a covalent adduct with the reduced Cys62 residue of the p50 subunit of the transcription factor NF‐κB through Michael addition reaction, leading to inhibition of the NF‐κB transcriptional activity (Nguyen et al., 2015). In a similar fashion, andrographolide has been shown to covalently bind to Keap1 to release Nrf2 to promote nuclear Nrf2 accumulation and endogenous antioxidant defence system (Yuan et al., 2012).

Several technical concerns are noticed in this study. The healthy subjects are generally younger than the COPD patients. Although a correlation analysis of the 12 healthy subjects of varying age did not reveal any age‐dependent corticosteroid insensitivity (data not shown), and to date, there is no literature available to address the impact of age difference on corticosteroid resistance, we speculate that age difference may partially contribute to the significant difference in corticosteroid sensitivity observed between the healthy subjects and the COPD patients in the present study. In addition, the current study did not include a healthy smoker group that the significant difference observed between the healthy subjects and the COPD patients may actually be due to cigarette smoking per se, instead of COPD. Nevertheless, To et al. (2010) reported that PBMCs from healthy non‐smokers and from healthy smokers did not show significant difference in corticosteroid sensitivity. Also, due to limited PBMC samples remaining for andrographolide studies, we had difficulty in detecting Nrf2 band in some samples for Figure 5c. A statistically insignificant but a clear upward trend of HDAC2 level induced by andrographolide, in the PBMCs from both HS and COPD patients in Figure 5c, might also be attributed to the limited PBMC samples remaining for andrographolide studies.

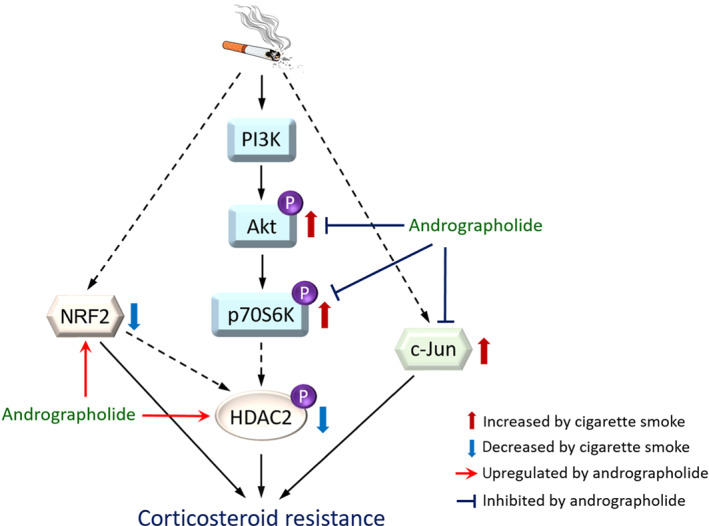

In conclusion, we report here for the first time that andrographolide could restore corticosteroid sensitivity in COPD models, at least partially through inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/p70S6K signalling pathway, leading to the restoration of nuclear HDAC2 level and activity, and reduction of nuclear c‐Jun level. Besides, andrographolide promotes the nuclear level of antioxidative transcription factor Nrf2, which helps to reduce oxidative stress and subsequently contributes to enhanced HDAC2 level as well (Figure 6). In summary, our findings support a novel therapeutic value for andrographolide to restore corticosteroid sensitivity in the treatment of COPD.

FIGURE 6.

A proposed corticosteroid re‐sensitization mechanism of andrographolide in COPD. Cigarette smoke down‐regulates Nrf2 level, up‐regulates c‐Jun expression, and stimulates PI3K/Akt/p706K signalling pathway, which leads to reduction of HDAC2 level, resulting in corticosteroid resistance in COPD. Andrographolide up‐regulates Nrf2 expression, reduces c‐Jun level, and blocks PI3K/Akt/p70S6K signalling pathway, resulting in restoration of HDAC2 level in COPD. HDAC2: histone deacetylase‐2; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2‐related factor 2; PI3K: phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase; p70S6K: p70 S6 kinase

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.S.F.W., J.A., A.Y.H.L., and W.L. participated in conception or design of the work. W.L. and W.S.D.T. conducted experiments and data acquisition. W.S.F.W. contributed reagents or analytic tools. W.L., W.S.D.T., and W.S.F.W. analysed and interpreted data. W.L., A.Y.H.L., and W.S.F.W. wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for Design & Analysis, Immunoblotting and Immunochemistry, and Animal Experimentation, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research work was supported by a grant R‐184‐000‐269‐592 from the National Research Foundation of Singapore (W.S.F.W.) and a bridging grant R‐184‐000‐267‐733 from NUHS (W.S.F.W.).

Liao W, Lim AYH, Tan WSD, Abisheganaden J, Wong WSF. Restoration of HDAC2 and Nrf2 by andrographolide overcomes corticosteroid resistance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:3662–3673. 10.1111/bph.15080

REFERENCES

- Adcock, I. M. , Lane, S. J. , Brown, C. R. , Lee, T. H. , & Barnes, P. J. (1995). Abnormal glucocorticoid receptor‐activator protein 1 interaction in steroid‐resistant asthma. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 182, 1951–1958. 10.1084/jem.182.6.1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adenuga, D. , Caito, S. , Yao, H. , Sundar, I. K. , Hwang, J. W. , Chung, S. , & Rahman, I. (2010). Nrf2 deficiency influences susceptibility to steroid resistance via HDAC2 reduction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 403, 452–456. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , & Veale, E. L. (2019). The concise guide to pharmacology 2019/20: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S297–S396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , & Armstrong, J. F. (2019). The concise guide to pharmacology 2019/20: Introduction and other protein targets. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S1–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Roberts, R. E. , Broughton, B. R. S. , Sobey, C. G. , George, C. H. , Stanford, S. C. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Goals and practicalities of immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry: A guide for submission to the British Journal of Pharmacology . British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 407–411. 10.1111/bph.14112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Harbi, N. O. , Nadeem, A. , Ahmad, S. F. , AlThagfan, S. S. , Alqinyah, M. , Alqahtani, F. , … Al‐Harbi, M. M. (2019). Sulforaphane treatment reverses corticosteroid resistance in a mixed granulocytic mouse model of asthma by upregulation of antioxidants and attenuation of Th17 immune responses in the airways. European Journal of Pharmacology, 855, 276–284. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Z. , Guan, S. , Cheng, C. , Wu, S. , Wong, S. H. , Kemeny, D. M. , … Wong, W. S. (2009). A novel antiinflammatory role for andrographolide in asthma via inhibition of the nuclear factor‐κB pathway. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 179, 657–665. 10.1164/rccm.200809-1516OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. (2009a). Histone deacetylase‐2 and airway disease. Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease, 3, 235–243. 10.1177/1753465809348648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. (2009b). Role of HDAC2 in the pathophysiology of COPD. Annual Review of Physiology, 71, 451–464. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. (2010). Mechanisms and resistance in glucocorticoid control of inflammation. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 120, 76–85. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. (2013). Corticosteroid resistance in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 131, 636–645. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. (2016). Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 138, 16–27. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Alexander, S. , Cirino, G. , Docherty, J. R. , George, C. H. , Giembycz, M. A. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: Updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 987–993. 10.1111/bph.14153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka, S. , Niu, J. , Schmidt, C. , Sclabas, G. M. , Peng, B. , Uwagawa, T. , … Chiao, P. J. (2004). NF‐κB and AP‐1 connection: Mechanism of NF‐κB‐dependent regulation of AP‐1 activity. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 24, 7806–7819. 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7806-7819.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S. P. , Tee, W. , Ng, D. S. , Chan, T. K. , Peh, H. Y. , Ho, W. E. , … Wong, W. S. (2013). Andrographolide protects against cigarette smoke‐induced oxidative lung injury via augmentation of Nrf2 activity. British Journal of Pharmacology, 168, 1707–1718. 10.1111/bph.12054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR . (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS guide to pharmacology in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to immunopharmacology. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z. , & Zhu, L. (2016). Update on molecular mechanisms of corticosteroid resistance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 37, 1–8. 10.1016/j.pupt.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny, C. , Browne, W. , Cuthill, I. C. , Emerson, M. , & Altman, D. G. (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: The ARRIVE guidelines. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160, 1577–1579. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W. , Tan, W. S. , & Wong, W. S. (2016). Andrographolide restores steroid sensitivity to block lipopolysaccharide/IFN‐γ‐induced IL‐27 and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Journal of Immunology, 196, 4706–4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, J. A. , Caramori, G. , Stevenson, C. S. , Casolari, P. , Jazrawi, E. , Barnes, P. J. , … Papi, A. (2009). Inhibition of PI3Kδ restores glucocorticoid function in smoking‐induced airway inflammation in mice. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 179, 542–548. 10.1164/rccm.200810-1570OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, S. M. , & Li, J. T. C. (2015). Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Healthcare costs and beyond. Allergy and Asthma Proc., 36, 4–10. 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, J. C. , & Lilley, E. (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): New requirements for publication in BJP . British Journal of Pharmacology, 172, 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado, N. , Hakim, A. , Kobayashi, Y. , Meah, S. , Usmani, O. S. , Chung, K. F. , … Ito, K. (2012). Restoration of corticosteroid sensitivity by p38 mitogen activated protein kinase inhibition in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from severe asthma. PLoS ONE, 7, e41582 10.1371/journal.pone.0041582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado, N. , Thimmulappa, R. , Thomas, C. M. , Fenwick, P. S. , Chana, K. K. , Donnelly, L. E. , … Barnes, P. J. (2011). Decreased histone deacetylase 2 impairs Nrf2 activation by oxidative stress. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 406, 292–298. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani, A. , Azam, A. , Vuppusetty, C. , Ito, K. , Mercado, N. , & Barnes, P. J. (2017). Quercetin restores corticosteroid sensitivity in cells from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Experimental Lung Research, 43, 417–425. 10.1080/01902148.2017.1393707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani, A. , Ito, K. , Vuppusetty, C. , Barnes, P. J. , & Mercado, N. (2016). Restoration of corticosteroid sensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 193, 143–153. 10.1164/rccm.201503-0593OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuschi, P. , & Ciabattoni, G. (2015). Bronchodilating drugs for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Current status and future trends. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 58, 4131–4164. 10.1021/jm5013227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. S. , Loh, X. Y. , Wijaya, H. , Wang, J. , Lin, Q. , Lam, Y. , … Mok, Y. K. (2015). Specificity and inhibitory mechanism of andrographolide and its analogues as antiasthma agents on NF‐κB p50. Journal of Natural Products, 78, 208–217. 10.1021/np5007179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, R. H. , & Cidlowski, J. A. (2013). The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: New signaling mechanisms in health and disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 132, 1033–1044. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peh, H. Y. , Tan, W. S. D. , Chan, T. K. , Pow, C. W. , Foster, P. S. , & Wong, W. S. F. (2017). Vitamin E isoform gamma‐tocotrienol protects against emphysema in cigarette smoke‐induced COPD. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 110, 332–344. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine, T. , Hirata, T. , Ishikawa, S. , Ito, S. , Ishimori, K. , Matsumura, K. , & Muraki, K. (2019). Regulation of NRF2, AP‐1 and NF‐κB by cigarette smoke exposure in three‐dimensional human bronchial epithelial cells. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 39, 717–725. 10.1002/jat.3761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, N. A. , Haskew‐Layton, R. E. , Basso, M. , Hushpulian, D. M. , Payappilly, J. B. , Speer, R. E. , … Gazaryan, I. G. (2011). Development of Neh2‐luciferase reporter and its application for high throughput screening and real‐time monitoring of Nrf2 activators. Chemistry & Biology, 18, 752–765. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W. S. , Peh, H. Y. , Liao, W. , Pang, C. H. , Chan, T. K. , Lau, S. H. , … Wong, W. S. (2016). Cigarette smoke‐induced lung disease predisposes to more severe infection with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: Protective effects of andrographolide. Journal of Natural Products, 79, 1308–1315. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W. S. D. , Liao, W. , Zhou, S. , & Wong, W. S. F. (2017). Is there a future for andrographolide to be an anti‐inflammatory drug? Deciphering its major mechanisms of action. Biochemical Pharmacology, 139, 71–81. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To, Y. , Ito, K. , Kizawa, Y. , Failla, M. , Ito, M. , Kusama, T. , … Barnes, P. J. (2010). Targeting Phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase‐δ with theophylline reverses corticosteroid insensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 182, 897–904. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0937OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Q. T. N. , Wong, W. S. F. , & Chai, C. L. L. (2017). Labdane diterpenoids as potential anti‐inflammatory agents. Pharmacological Research, 124, 43–63. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedzicha, J. A. , Calverley, P. M. , & Rabe, K. F. (2016). Roflumilast: A review of its use in the treatment of COPD. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 11, 81–90. 10.2147/COPD.S89849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. , Ji, L. , Luo, L. , Lu, J. , Ma, X. , Ma, Z. , & Chen, Z. (2012). Quinone reductase (QR) inducers from Andrographis paniculata and identification of molecular target of andrographolide. Fitoterapia, 83, 1506–1513. 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]