Abstract

It is well documented that Epichloë endophytes can enhance the resistance of grasses to herbivory. However, reports on resistance to pathogenic fungi are limited, and their conclusions are variable. In this study, we chose pathogenic fungi with different trophic types, namely, the biotrophic pathogen Erysiphales species and the necrotrophic pathogen Curvularia lunata, to test the effects of Epichloë on the pathogen resistance of Achnatherum sibiricum. The results showed that, compared to Erysiphales species, C. lunata caused a higher degree of damage and lower photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) in endophyte−free (E−) leaves. Endophytes significantly alleviated the damage caused by these two pathogens. The leaf damaged area and Fv/Fm of endophyte−infected (E+) leaves were similar between the two pathogen treatments, indicating that the beneficial effects of endophytes were more significant when hosts were exposed to C. lunata than when they were exposed to Erysiphales species. We found that A. sibiricum initiated jasmonic acid (JA)−related pathways to resist C. lunata but salicylic acid (SA)–related pathways to resist Erysiphales species. Endophytic fungi had no effect on the content of SA but increased the content of JA and total phenolic compounds, which suggest that endophyte infection might enhance the resistance of A. sibiricum to these two different trophic types of pathogens through similar pathways.

Keywords: Achnatherum sibiricum, endophyte, jasmonic acid, pathogens, trophic type

Introduction

Plant diseases are consistently among the important factors restricting the quality and yield of crops. It is estimated that plant diseases, 70∼80% of which are caused by pathogenic fungi, lead to an average loss of 10∼15% of the world’s major cash crops and direct economic losses of hundreds of billions of dollars each year (Strange and Scott, 2005; Kang, 2010). Depending on the ways in which nutrients are obtained from host cells, plant pathogenic fungi are classified as biotrophs, necrotrophs, or hemibiotrophs (Niks and Marcel, 2009). Biotrophic fungi obtain nutrients only from living host cells; necrotrophic fungi kill the host cells and then extract nutrients from the dead cells for their own growth and reproduction, and hemibiotrophic fungi grow like biotrophs in the initial stage of host cell infection and then turn into a necrotrophic phase (Perfect and Green, 2001; Niks and Marcel, 2009; Kou and Naqvi, 2016).

Phytohormones, such as jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA), are the central defense signaling molecules that regulate the defense responses of plants to pathogens. In Arabidopsis thaliana, Thomma et al. (1998) found that the npr1 mutation, which blocked SA signaling, resulted in greater susceptibility to the biotrophic fungus Peronospora parasitica but had no effect on resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria brassicicola. Conversely, the coi1 mutation, which blocked JA signaling, severely compromised resistance to the necrotrophic fungus A. brassicicola but had no effect on resistance to P. parasitica. Such results indicated that plants may initiate different defense mechanisms in response to different trophic types of pathogenic fungi, with SA−dependent defenses acting against biotrophs and JA−dependent responses acting against necrotrophs (Glazebrook, 2005). Both SA and JA can enhance the activity of enzymes in the phenylpropane pathway in plants and induce the synthesis of phenolic compounds (Neerja et al., 2013; Islam et al., 2019b). Plant phenolics are involved in disease resistance mechanisms in a variety of pathosystems, and phytohormones act as significant regulatory factors of disease tolerance (Cheynier et al., 2013; Islam et al., 2019a).

Endophytic fungi of genus Epichloë form symbiotic relationships with cold−season grasses (Tanaka et al., 2012). Endophytes obtain nutrients from host plants (Clay and Schardl, 2002) and in return might promote host growth (Malinowski et al., 1998; Li et al., 2012) and enhance the tolerance of host plants to abiotic and biotic stresses such as drought (Bouton et al., 1993; Tanaka et al., 2012) and herbivory (Tanaka et al., 2005; Baldauf et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2016). In addition, Epichloë can affect the disease resistance of host plants, but the direction of influence is not consistent. To date, positive, neutral, and even negative effects have been reported. For example, Epichloë enhanced the resistance of Festuca arundinacea and Lolium perenne hosts to Rhizoctonia zeae (Christensen, 1996; Pańka et al., 2013b) but had no significant effects on the resistance of Festuca pratensis to Puccinia graminis or Fusarium oxysporum (Welty et al., 1993; Trevathan, 1996; Pańka et al., 2011). Wäli et al. (2006) even found that Lolium pratense infected by Epichloë was more sensitive than uninfected L. pratense to Typhula ishikariensis. We hypothesize that the inconsistencies in the effects of Epichloë on the resistance of host grasses are related not only to the species of symbiont but also to the trophic mode of pathogenic fungi.

It is well known that endophyte infection can improve herbivore resistance of the host grasses due to production of alkaloids (Clay and Cheplick, 1989; Ball et al., 1997; Bush et al., 1997; Schardl et al., 2013). However, alkaloids are not likely directly associated with fungal pathogen resistance (Siegel and Latch, 1991; Holzmann et al., 2000; Schardl et al., 2013; Bastías et al., 2017). Then, how does endophyte infection improve pathogen resistance of the host? The pioneering research by Malinowski et al. (1998) found that Epichloë endophytes increased the production of phenolic compounds in roots of F. arundinacea, and similar results were reported in L. perenne (Pańka et al., 2013a; Pierre et al., 2015). Thus, the elevated levels of total phenolic compounds might be correlated with plant resistance to pathogenic fungi. Recently, Bastías et al. (2018a, b) found that symbiotic plants had lower concentrations of SA than their non-symbiotic plants, and SA/JA treatment decreased the endophyte-conferred resistance against aphids. These results indicated that SA/JA might play a critical role in regulating the endophyte-conferred resistance against herbivores. Therefore, studies on this subject about SA/JA involved in pathogen resistance of Epichloë-infected grasses are very limited (Wang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2019).

Achnatherum sibiricum is a perennial, sparse bunchgrass that is widely distributed in Northeast China and is usually colonized by Epichloë endophytes with high infection rates (86–100%) in natural habitats (Wei et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). Within the genus Achnatherum, two other species, Achnatherum inebrians and Achnatherum robustum, have been reported to be infected by Epichloë endophytes. Both are notorious for their narcotic properties in livestock and hence are named as “drunken horse grass” and “sleepy grass,” respectively (Petroski et al., 1992; Bruehl et al., 1994). Achnatherum inebrians can be infected by Epichloë gansuensis and Epichloë inebrians (Chen L. et al., 2015), and A. robustum by Epichloë funkii (Moon et al., 2007). As for A. sibiricum, it can harbor two different Epichloë species, Epichloë sibirica and E. gansuensis. The phenomenon of double infections by both Epichloë species in the same plant has not been observed in A. sibiricum (Zhang et al., 2009; Li et al., 2015). Both E. sibirica and E. gansuensis improved the growth and competitive ability of A. sibiricum (Li et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2019), and their main metabolites were also similar (our unpublished data). According to many years of observations in our laboratory, A. sibiricum exhibits no obvious herbivore deterrence, but its pathogen damage is usually less serious than in most neighboring plants of other species. In this study, Epichloë−infected and Epichloë−free A. sibiricum were used as plant materials, and a biotrophic fungus, Erysiphales species (powdery mildew), and the necrotrophic fungus, Curvularia lunata were selected as pathogens. The following questions were addressed: (1) Can Epichloë improve the resistance of A. sibiricum to pathogens? (2) Is the influence of endophytic fungi on the disease resistance of host plants related to the trophic types of pathogens? (3) What is the possible mechanism?

Materials and Methods

Plant and Pathogenic Fungi Materials

Seeds of A. sibiricum were collected from the Stipa baicalensis sampling area of Yimin in the National Hulunbuir Grassland Ecosystem Observation and Research Station of China (119.669°E, 48.493°N). Detection of endophytic fungus was carried out on the seeds by the aniline blue–lactic acid staining method (Latch et al., 1984), and their endophyte infection rates were 100%. Endophyte−free (E−) seeds were obtained from endophyte−infected (E+) seeds by high−temperature treatment (60°C) for 30 days (Li et al., 2010). Earlier work in our laboratory showed that the high−temperature processing had no significant effects on the seed germination rate (Li et al., 2010) and was an effective disinfection method for A. sibiricum (Ren et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012). In the previous study of our laboratory, the effect of different species of endophytes on fungal disease resistance of A. sibiricum was studied, and the results showed that the resistance of A. sibiricum was not affected by endophyte species (Niu et al., 2016). Therefore, in this study, we did not discriminate endophyte species, and the seeds were infected by either E. sibirica or E. gansuensis.

The seeds were surface sterilized with 2% NaClO solution for 5 min, flushed with sterile water for 3 times, and then placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Sangon Biotech Company, Shanghai, China) in the dark at 25°C. After 4 weeks, only E. sibirica or E. gansuensis was isolated from E+ seeds, but no microbe was isolated from E− seeds. Thirty sterilized seeds were evenly spread in each pot (200 mm in diameter and 220 mm in depth) filled with sterilized vermiculite. After 45 days, the endophyte status of all plants was checked microscopically by examining the upper epidermis of leaf sheaths stained with lactophenol containing aniline blue (Latch and Christensen, 1985). The endophyte−infected proportions of E+ plants were 100%, and endophyte−free proportions of E− plants were zero. Twenty plants of approximately equal size (approximately 15 cm high) were maintained in one pot.

Erysiphales species was collected from the diseased leaves of A. sibiricum. To purify the pathogen, we cut from the margins of actively growing fungal colonies and immediately placed in petri dishes containing 1% (wt/vol) distilled water agar and 8.5 mM benzimidazole (Wang et al., 2014). A single colony of Erysiphales species was transferred to inoculate a healthy plant, and this process was repeated three times. Curvularia lunata was purchased from the Agricultural Culture Collection of China. A spore suspension of C. lunata, which was cultured on PDA for 15 days at 28°C, was prepared by washing the hyphae of the pathogenic fungus with sterile water (containing 0.02% Tween 20) and filtering with double layers of sterile gauze. The concentration of the pathogen spore suspension counted by hemocytometer was 1.4 × 106 spores/mL, and the spore germination rate was 87%.

Experimental Design

The experiment followed a randomized block design with two factors. The first factor was the Epichloë endophyte status, including E+ and E−. The second factor was the inoculation of pathogenic fungi, including the following three treatments: control (CK), C. lunata, and Erysiphales species. Each combination was replicated 10 times, yielding a total of 60 pots. The experiment was conducted in the greenhouse at Nankai University, Tianjin, China. Plants were subjected to ambient light, and the room temperature was 20–30°C. During the experiment, each pot was watered once a week with one-half strength Hoagland nutrient solution. The experiment began on November 1, 2018, and lasted for 3 months.

Inoculation of Pathogenic Fungi

The leaves were inoculated with C. lunata by spraying them with the spore suspension until liquid dripped from them, and CK was sprayed with sterile water containing 0.02% Tween 20. For the inoculation of Erysiphales species, the conidia collected from the cultured plants were blown uniformly onto E+ and E− plants with a hair dryer according to Li’s method (Li et al., 2018). After inoculation, all tested plants were transferred to transparent storage boxes, where high humidity was maintained to promote the disease on leaves.

Observation of Leaf Damage

Fully expanded diseased leaves collected randomly 0, 3, and 7 days after pathogen inoculation were examined by scanning electron microscopy (Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope, FEI; Portland, Oregon, United States) (Becker et al., 2016), and the tissue structure and mycelia on the blade surface were observed.

On the seventh day, 10 plant leaves were randomly sampled and stained by trypan blue under each treatment (Michael et al., 2018). The damaged leaf areas were stained blue, whereas the healthy areas were colorless. These stained leaves were photographed one by one with a digital camera. Then, we calculated the proportion of the trypan blue–stained area of leaf photos using ImageJ software (Taheri and Kakooee, 2017).

Measurement of Response Variables

After 7 days of pathogen infection, Fv/Fm, the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II in the dark−adapted state, was recorded on the disease spot with a Fluorpen FP 110 handheld fluorometer (Pneumatic System International; Brno, Czech Republic), and Fv/Fm of CK leaves on the same site was also recorded.

Freeze−dried leaf samples of 0.3–0.5 g (fresh weight) were taken for quantification of SA and JA. The SA content was quantified using high−performance liquid chromatography (Waters 1500−series; Micromass UK Ltd., Manchester, United Kingdom) on a C18 reverse−phase column following Wang’s method with modification (Wang et al., 2016). The JA content was quantified by enzyme−linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (JA ELISA Kit; Shanghai Yingxin Laboratory, Shanghai, China).

Approximately 0.3 g leaf samples (dry weight) were taken for qualification of total phenolic compounds. The total phenolic compounds content was determined by Folin−Ciocalteu colorimetry with Shimadzu UV-1800 double-beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu; Kyoto, Japan) (Chen L. Y. et al., 2015).

Data Analyses

All data analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, New York, United States). Two−way analysis of variance was used to analyze the effects of endophyte infection and pathogen inoculation on all response variables of A. sibiricum. The differences among means were compared using Duncan multiple−range test, with significance at P < 0.05.

Results

Microscopic Observations

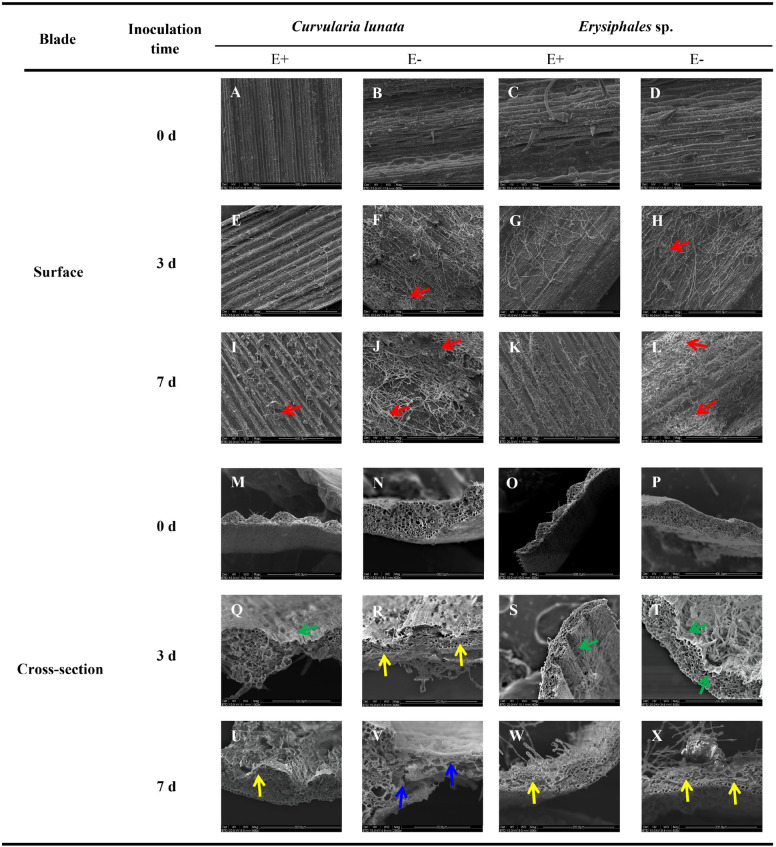

Before pathogen inoculation, the surface structure was similar in E+ and E- leaves (Figures 1A–D). After pathogen inoculation, scanning electron microscopy revealed that the mycelial density of pathogens in E− leaves was higher than that in E+ leaves at the same time after inoculation of C. lunata or Erysiphales species (Figures 1E–L). When inoculated with C. lunata, infection cushions first appeared on the surface of E− leaves on the third day (Figures 1F,H). For E+ leaves, no infection cushions were observed in response to infection by C. lunata until 7 days after inoculation (Figures 1E,G,I,K), and the levels were lower than those observed on E− leaves (Figures 1I,J). When inoculated with Erysiphales species, infection cushions appeared on the surface of E− leaves on the third and seventh day (Figures 1H,L), but no infection cushions were observed on E+ leaves (Figures 1G,K).

FIGURE 1.

Scanning electron microscopy observation of structures of E+ and E− A. sibiricum leaves infected by pathogens. Images A-L indicate the surface of E+ and E- leaves inoculated by C. lunata or Erysiphales sp. on Day 0 (A–D), 3 (E–H), and 7 (I–L), respectively. Images M-X indicate the cross-section of E+ and E- leaves inoculated by C. lunata or Erysiphales sp. on Day 0 (M–P), 3 (Q–T) and 7 (U–X), respectively. Red arrows indicate infection cushions; green arrows indicate crumpling cell walls; yellow arrows indicate collapsed cell walls, and blue arrows indicate fragmented cell walls.

The degree of damage to leaf cell walls (integrity, crumpling, collapse, and fragmentation) was an important indicator of plant disease resistance. The cross-section structure of E+ and E- leaves was integrity before pathogen inoculation (Figures 1M–P). The damage to leaf structure caused by C. lunata inoculation was more severe than that caused by Erysiphales species, and the endophytic fungi alleviated the damage caused by both pathogens (Figures 1Q–X). When inoculated with C. lunata, crumpling cell walls were observed on the third day (Figure 1Q), and the mesophyll cells began to collapse on the seventh day in E+ leaves (Figure 1U). For E− leaves, the mesophyll cells began to collapse on the third day (Figure 1R), and the whole cross−section cell structure was completely fragmented on the seventh day (Figure 1V). Under inoculation with Erysiphales species, crumpling cell walls were observed at the infection site on the third day (Figures 1S,T), and the epidermal cells showed collapse on the seventh day in both E+ and E− leaves (Figures 1W,X), but the degree of crumpling and collapse was more severe in E− leaves.

Leaf Damage

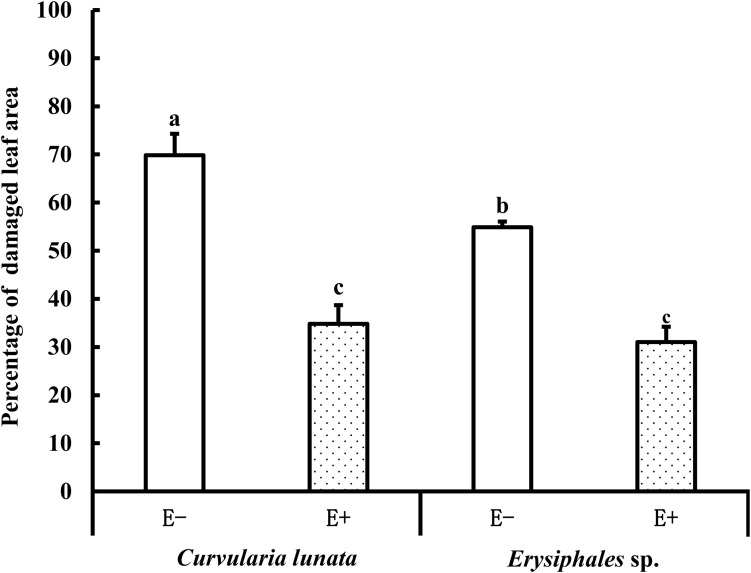

The proportions of damaged leaf area were affected by endophytes and pathogens (Table 1 and Figure 2). In E− leaves, C. lunata caused a significantly higher proportion of damaged leaf area (70%) than Erysiphales species (55%). Endophytes significantly alleviated the damage caused by these two pathogens. In E+ leaves, the proportion of damaged leaf area was similar for the two pathogens. These results indicated that the beneficial effects of endophytes were more significant when hosts were exposed to C. lunata than when they were exposed to Erysiphales species.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of variance of the effects of the endophyte (E) and pathogens (P) on the leaf damage area, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, total phenolic compounds content, and SA/JA content of A. sibiricum.

| Leaf damage | Total phenolic | |||||||||

| Treatment | area |

Fv/Fm |

compounds |

SA |

JA |

|||||

| F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | |

| Endophyte (E) | 74.75 | <0.001 | 117.088 | <0.001 | 43.264 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.934 | 79.429 | <0.001 |

| Pathogens (P) | 7.573 | 0.009 | 213.647 | <0.001 | 108.609 | <0.001 | 442.789 | <0.001 | 17.663 | <0.001 |

| E*P | 2.692 | 0.110 | 52.973 | <0.001 | 13.973 | <0.001 | 1.151 | 0.333 | 1.035 | 0.370 |

Significant P-values (P < 0.05) are shown in bold font.

FIGURE 2.

The leaf damage area of E+ and E− A. sibiricum leaves infected by pathogens. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Bars represent mean values ± standard error (SE) (n = 10).

Chlorophyll Fluorometry

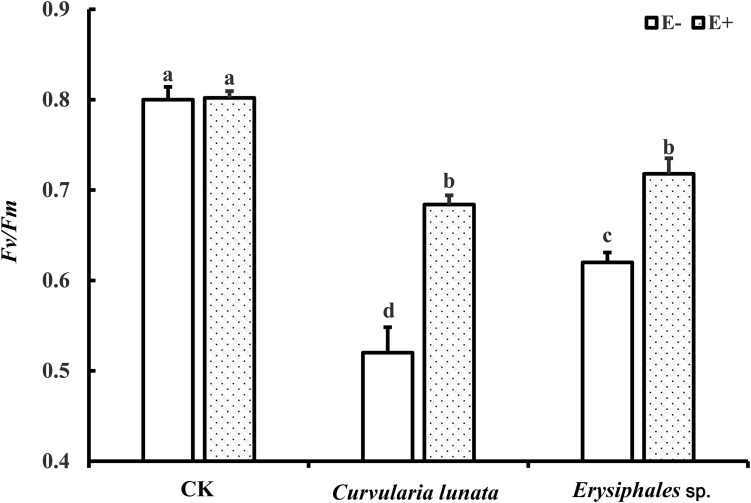

The endophyte, pathogens, and their interaction all had significant effects on Fv/Fm (Table 1). In the control group without pathogens, the Fv/Fm of A. sibiricum leaves showed no significant difference between E+ and E− leaves (Figure 3). Pathogen inoculation significantly reduced the Fv/Fm of both E+ and E− leaves. For E− leaves, the adverse effect of C. lunata (reduced by 35% compared to that in CK) was significantly stronger than that of Erysiphales species (reduced by 23% compared to that in CK). The endophyte alleviated the decline in Fv/Fm in leaves infected by both pathogens. For E+ leaves, similar Fv/Fm values were observed in leaves infected by both pathogens, which suggested that the beneficial effect of endophyte infection was more significant when leaves were inoculated by C. lunata than when they were inoculated by Erysiphales species.

FIGURE 3.

The Fv/Fm of E+ and E− A. sibiricum leaves infected by pathogens. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5).

Content of SA and JA

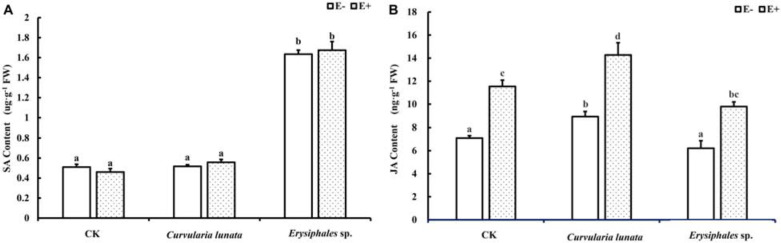

Both endophytic fungi and pathogens significantly affected the content of JA in A. sibiricum, whereas the content of SA was only affected by pathogens (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the SA content between E+ and E− leaves in CK (Figure 4A), but the JA content in E+ was significantly higher than in E− (increased 63%) (Figure 4B). Compared with CK, inoculation by C. lunata did not affect the SA content in either E+ or E− leaves, but increased the JA content in both E+ and E− leaves, and the JA content in E+ was 60% higher than that in E−. When inoculated by Erysiphales species, the SA content was significantly increased in both E+ and E−, and there was no significant difference between E+ and E−. Inoculated by Erysiphales species did not affect the JA content in either E+ or E−, but the JA content in E+ was 58% higher than that in E−.

FIGURE 4.

The salicylic acid (A) and jasmonic acid (B) content of E+ and E− A. sibiricum leaves infected by pathogens. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5).

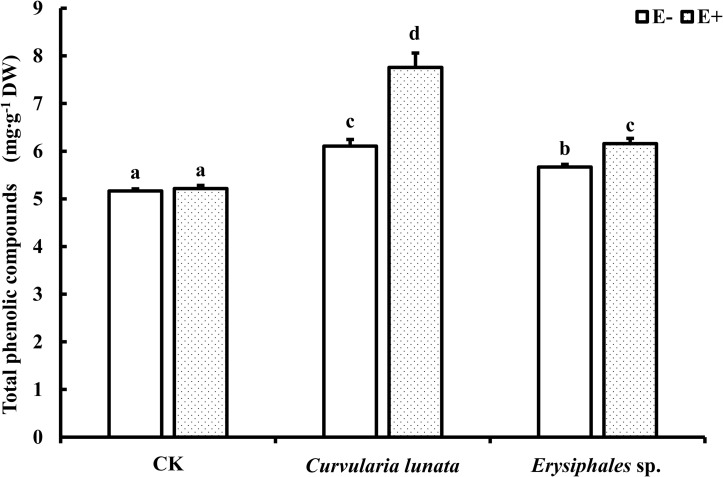

Total Phenolic Compounds Content

The endophyte, pathogens, and their interaction significantly affected the content of total phenolics (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the total phenolic content between E+ and E− leaves in CK (Figure 5). Compared with CK, inoculation by the two pathogens caused a significant increase in the total phenolic content in leaves, and the total phenolic content of the leaves infected by C. lunata was higher than that of the leaves infected by Erysiphales species. The endophyte significantly increased the content of total phenolics in leaves infected by C. lunata and Erysiphales species by 27 and 8.7%, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

The total phenolic compounds content of E+ and E− A. sibiricum leaves infected by pathogens. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05). Bars represent mean values ± SE (n = 5).

Discussion

Since Shimanuki and Sato (1983) first found that endophytic Epichloë could significantly reduce damage caused by Blastocladia pringsheimii in Phleum pratense, at least 15 grass–endophyte symbioses have been studied in the context of resistance to pathogens (Wiewióra et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2018). Most studies reported that Epichloë can improve the disease resistance of host, but several studies have found that endophytes have no effect on the disease resistance of the host or even have adverse effects (Welty et al., 1993; Wäli et al., 2006; Pańka et al., 2013a). Considering that pathogenic capacity differs among pathogen trophic types, necrotrophic pathogens are more destructive than biotrophic pathogens (Joanna et al., 2012; Kou and Naqvi, 2016). Therefore, is the effect of endophyte infection on host plant disease resistance related to the trophic types of pathogens? Previous research focused on pathogens of different trophic types by using different grass–Epichloë symbioses. For necrotrophic pathogenic fungi, the beneficial effects of endophyte infection have been reported in many grass species (Clarke et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2015; Wiewióra et al., 2015). For biotrophic pathogenic fungi, however, there are limited and varied results. Endophyte infection enhanced the resistance of A. inebrians to Blumeria graminis (Xia et al., 2015) and Lolium multiflorum to Claviceps purpurea (Perez et al., 2017), but had no effect on F. pratensis against B. graminis (Sabzalian et al., 2012).

The leaf spot diseases are widely distributed around northern China and can damage a variety of plants including grasses (Liu, 2011; Wei et al., 2011; Yue et al., 2019). In this study, we chose pathogens of different trophic types to inoculate the host in A. sibiricum–Epichloë symbiosis. The results showed that, compared to Erysiphales species, C. lunata caused a higher degree of damage and lower photochemical efficiency in E− leaves. The endophyte significantly alleviated the damage caused by these two pathogens to plant leaves. Similar Fv/Fm values and percentage of damaged leaf areas were observed between the two pathogen inoculation treatments in E+ leaves, indicating that the beneficial effects of the endophyte were greater against C. lunata than against Erysiphales species.

Salicylic acid is a plant signaling molecule that acts in response to biotrophic pathogens (White, 1979; Michael et al., 2018). In this study, we found that the content of SA in A. sibiricum leaves did not significantly change in response to inoculation by C. lunata but was significantly induced by Erysiphales species. The presence of endophytic fungi had no significant effect on the SA content in A. sibiricum leaves. In previous studies in our laboratory, Wang et al. (2016) also found that endophytes had no effect on the concentration of SA in Leymus chinensis infected by C. lunata or Bipolaris sorokiniana, indicating that the improvement of host disease resistance due to the endophyte was not regulated by SA.

Jasmonic acid is also an important signaling molecule in plant disease resistance responses. Many studies have shown that plants initiate JA−dependent responses upon exposure to necrotrophs (Mengiste, 2012; Qi et al., 2012; Pandey et al., 2016; Islam et al., 2018). In the present study, the content of JA in E+ and E− leaves was not affected by the biotrophic pathogen Erysiphales species but was increased by the necrotrophic pathogen C. lunata, which was consistent with the conclusions of previous research. In this study, we found that endophyte infection significantly increased the JA content in infected host grass leaves, regardless of which pathogen was inoculated, indicating that endophytic fungi may enhance the disease resistance of A. sibiricum hosts via the JA−mediated pathway.

Plants reportedly respond to inoculation of necrotrophic pathogens and biotrophic pathogens via the JA and SA pathways, respectively (Glazebrook, 2005; Vos et al., 2013), which was also demonstrated in this study. In this study, we further found that Epichloë enhanced the disease resistance of A. sibiricum host, probably via the JA−mediated pathway, not the SA pathway. Similar results have also been reported by Wang et al. (2016), who found endophyte infection enhanced the disease resistance of L. chinensis without affecting SA concentration of the host. Unfortunately, JA was not tested in that study. In contrast, Guo et al. (2019) found that endophyte infection improved the pathogen resistance of L. perenne but did not induce the increase of JA content. In addition, the effects of endophyte infection on SA/JA content have been reported by other studies, although their relationship with pathogen resistance was not considered. For example, Epichloë occultans significantly reduced SA concentrations but had no effect on the JA concentration in L. multiflorum (Bastías et al., 2018a, 2019). On the contrary, Ambrose et al. (2015) found that Epichloë endophyte in red fescue had a null or positive effect on SA concentration, depending on the plant tissue (leaf/sheath) and the endophyte. The diverse effects of endophyte infection on SA/JA concentration suggest that different pathogen resistance mechanisms might occur in different Epichloë–grass symbionts.

Phenolic compounds are important secondary metabolites in the plant disease resistance response (Cheynier et al., 2013). Plants can synthesize phenolic compounds such as tannins, coumaric acid, and ferulic acid to inhibit pathogenic activity (Blodgett et al., 2003; Yang and Gao, 2009; Bento et al., 2018) and produce lignin to resist pathogen invasion (Hématy et al., 2009). In the present study, the endophyte did not significantly affect the content of total phenolic compounds in the control but promoted the accumulation of total phenolic compounds in plant leaves regardless of which pathogen was inoculated. These results suggested that Epichloë could improve the disease resistance of A. sibiricum by promoting the synthesis of phenolic compounds. The enhancement of total phenolic compounds content of host grasses by endophyte infection to resist pathogens has also been reported in perennial ryegrass (Pańka et al., 2013a).

Conclusion

Our study found that A. sibiricum initiated JA−related pathways to resist the necrotrophic pathogen C. lunata, while initiated SA−related pathways to resist the biotrophic pathogen Erysiphales species. Epichloë endophytes significantly alleviated the leaf damage caused by the two trophic types of pathogens, and the beneficial effects were more significant when hosts were exposed to C. lunata than when they were exposed to Erysiphales species. Endophytic fungi had no effect on the SA content but increased the content of JA and total phenolic compounds, which suggest that endophyte infection might probably enhanced the resistance of A. sibiricum to different trophic types of pathogens through similar pathways. It is worth noting that our results might have been different if different Epichloë–grass symbionts were studied, but the present study highlights that the interaction between the plant JA hormone and endophytes infection can affect the pathogen resistance of symbiotic plants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

AR, XS, and YG designed the research. XS, MW, HL, TQ, JL and YS performed the experiments. XS and AR analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. AR revised and polished the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0500702), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971425), and Ph.D. Candidate Research Innovation Fund of Nankai University.

References

- Ambrose K. V., Tian Z., Wang Y., Smith J., Belanger F. C. (2015). Functional characterization of salicylate hydroxylase from the fungal endophyte Epichloë festucae. Sci. Rep. 5:10939. 10.1038/srep10939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf M. W., Mace W. J., Richmond D. S. (2011). Endophyte-mediated resistance to black cutworm as a function of plant cultivar and endophyte strain in tall fescue. Environ. Entomol. 40 639–647. 10.1603/EN09227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball O. J. P., Miles C. O., Prestidge R. A. (1997). Ergopeptine alkaloids and Neotyphodium lolii-mediated resistance in perennial ryegrass against adult Heteronychus arator (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 90 1382–1391. 10.1093/jee/90.5.1382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías D. A., Alejandra M. G. M., Ballaré C. L., Gundel P. E. (2017). Epichloë fungal endophytes and plant defenses: not just alkaloids. Trends Plant Sci. 22 939–948. 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías D. A., Alejandra M. G. M., Newman J. A., Card S. D., Mace W. J., Gundel P. E. (2018a). The plant hormone salicylic acid interacts with the mechanism of anti-herbivory conferred by fungal endophytes in grasses. Plant Cell Environ. 41 395–405. 10.1111/pce.13102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías D. A., Alejandra M. G. M., Newman J. A., Card S. D., Mace W. J., Gundel P. E. (2018b). Jasmonic acid regulation of the anti-herbivory mechanism conferred by fungal endophytes in grasses. J. Ecol. 106 2365–2379. 10.1111/1365-2745.12990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías D. A., Alejandra M. G. M., Newman J. A., Card S. D., Mace W. J., Gundel P. E. (2019). Sipha maydis sensitivity to defences of Lolium multiflorum and its endophytic fungus Epichloë occultans. PeerJ 7:e8257. 10.7717/peerj.8257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M., Becker Y., Green K., Scott B. (2016). The endophytic symbiont Epichloë festucae establishes an epiphyllous net on the surface of Lolium perenne leaves by development of an expressorium, an appressorium-like leaf exit structure. New Phytol. 211 240–254. 10.1111/nph.13931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento S. A., Patto M. C. V., Do R. B. M. (2018). Relevance, structure and analysis of ferulic acid in maize cell walls. Food Chem. 246 360–378. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett J. T., Bonello P., Stanosz G. R. (2003). An effective medium for isolating Sphaeropsis sapinea from asymptomatic pines. Forest Pathol. 33 395–404. 10.1046/j.1437-4781.2003.00342.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton J., Gates R., Belesky D., Owsley M. (1993). Yield and persistence of tall fescue in the southeastern coastal plain after removal of its endophyte. Agron. J. 85 52–55. 10.2134/agronj1993.00021962008500010011x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl G., Kaiser W., Klein R. (1994). An endophyte of Achnatherum inebrians, an intoxicating grass of northwest China. Mycologia 86 773–776. 10.1080/00275514.1994.12026482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush L. P., Wilkinson H. H., Schardl C. L. (1997). Bioprotective alkaloids of grass-fungal endophyte symbioses. Plant Physiol. 114:1. 10.1104/pp.114.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Li X., Li C., Swoboda G. A., Young C. A., Sugawara K., et al. (2015). Two distinct Epichloë species symbiotic with Achnatherum inebrians, drunken horse grass. Mycologia 107 863–873. 10.3852/15-019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Y., Cheng C. W., Liang J. Y. (2015). Effect of esterification condensation on the Folin–Ciocalteu method for the quantitative measurement of total phenols. Food Chem. 170 10–15. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheynier V., Comte G., Davies K. M., Lattanzio V., Martens S. (2013). Plant phenolics: recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 72 1–20. 10.3852/15-019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. (1996). Antifungal activity in grasses infected with Acremonium and Epichloë endophytes. Austral. Plant Pathol. 25 186–191. 10.1071/AP96032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke B. B., James F., White J., Richard H., Hurley A., Torres M. S. (2006). Endophyte-mediated suppression of dollar spot disease in fine fescues. Plant Dis. 90 994–998. 10.1094/PD-90-0994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay K., Cheplick G. P. (1989). Effect of ergot alkaloids from fungal endophyte-infected grasses on fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). J. Chem. Ecol. 15 169–182. 10.1007/BF02027781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay K., Schardl C. (2002). Evolutionary origins and ecological consequences of endophyte symbiosis with grasses. Am. Nat. 160 S99–S127. 10.1086/342161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43 205–227. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Gao P., Li F., Duan T. (2019). Effects of AM fungi and grass endophytes on perennial ryegrass Bipolaris sorokiniana leaf spot disease under limited soil nutrients. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 154 659–671. 10.1007/s10658-019-01689-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hématy K., Cherk C., Somerville S. (2009). Host–pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 406–413. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzmann W. A., Dapprich P., Eierdanz S., Heerz D., Paul V. (2000). “Anti-fungal substances extracted from Neotyphodium endophytes,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Harmful and Beneficial Microorganisms in Grassland, Pasture and Turf, Soest, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Islam M., Hussain H., Rookes J., Cahill D. (2018). Transcriptome analysis, using RNA-Seq of Lomandra longifolia roots infected with Phytophthora cinnamomi reveals the complexity of the resistance response. Plant Biol. 20 130–142. 10.1111/plb.12624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. T., Lee B. R., Lee H., Jung W. J., Bae D. W., Kim T. H. (2019a). p-Coumaric acid induces jasmonic acid-mediated phenolic accumulation and resistance to black rot disease in Brassica napus. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 106 270–275. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. T., Lee B. R., Park S. H., Jung W. J., Bae D. W., Kim T. H. (2019b). Hormonal regulations in soluble and cell-wall bound phenolic accumulation in two cultivars of Brassica napus contrasting susceptibility to Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Plant Sci. 285 132–140. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna L., Macioszek V. K., Kononowicz A. K. (2012). Plant-fungus interface: the role of surface structures in plant resistance and susceptibility to pathogenic fungi. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 78 24–30. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2012.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z. S. (2010). Current status and development strategy for research on plant fungal diseases in China. Plant Protect. 36 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kou Y., Naqvi N. I. (2016). Surface sensing and signaling networks in plant pathogenic fungi. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 57 84–92. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latch G. C., Christensen M. J. (1985). Artificial infection of grasses with endophytes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 107 17–24. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1985.tb01543.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latch G. C., Christensen M. J., Samuels G. J. (1984). Five endophytes of Lolium and Festuca in New Zealand. Mycotaxon 20 535–550. [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Xia C., Zhong R., Ju Y., Nan Z., Christensen M. J., et al. (2018). Interactive effects of water stress and powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis) on the alkaloid production of Achnatherum inebrians infected by Epichloë endophyte. Sci. China Life Sci. 61 1–2. 10.1007/s11427-017-9245-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Han R., Ren A. Z., Gao Y. B. (2010). Using high-temperature treatment to construct endophyte-free Achnatherum sibiricum. Microbiol. China 37 1395–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Ren A., Han R., Yin L., Wei M., Gao Y. (2012). Endophyte-mediated effects on the growth and physiology of Achnatherum sibiricum are conditional on both N and P availability. PLoS One 7:e48010. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhou Y., Wade M., Qin J., Liu H., Chen W., et al. (2016). Endophyte species influence the biomass production of the native grass Achnatherum sibiricum (L.) Keng under high nitrogen availability. Ecol. Evol. 6 8595–8606. 10.1002/ece3.2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhou Y., Zhu M., Qin J., Ren A., Gao Y. (2015). Stroma-bearing endophyte and its potential horizontal transmission ability in Achnatherum sibiricum. Mycologia 107 21–31. 10.3852/13-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. (2011). Flora diversity of powdery mildews in Inner Mongolia. J. Fungal Res. 9 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski D. P., Alloush G. A., Belesky D. P. (1998). Evidence for chemical changes on the root surface of tall fescue in response to infection with the fungal endophyte Neotyphodium coenophialum. Plant Soil 205 112 10.1023/A:1004331932018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Christensen M. J., Nan Z. B. (2015). Effects of the endophyte Epichloë festucae var. lolii of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) on indicators of oxidative stress from pathogenic fungi during seed germination and seedling growth. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 141 571–583. 10.1007/s10658-014-0563-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mengiste T. (2012). Plant immunity to necrotrophs. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50 267–294. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael H., Tatyana Z., Friederike B., Vanessa R. D., Denis K., Michele H., et al. (2018). Flavin monooxygenase-generated N-hydroxypipecolic acid is a critical element of plant systemic immunity. Cell 173 456–469. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C. D., Guillaumin J. J., Ravel C., Li C., Craven K. D., Schardl C. L. (2007). New Neotyphodium endophyte species from the grass tribes Stipeae and Meliceae. Mycologia 99 895–905. 10.1080/15572536.2007.11832521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neerja S., Sohal B., Lore J. (2013). Foliar application of benzothiadiazole and salicylic acid to combat sheath blight disease of rice. Rice Sci. 20 349–355. 10.1016/S1672-6308(13)60155-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niks R. E., Marcel T. C. (2009). Nonhost and basal resistance: how to explain specificity? New Phytol. 182 817–828. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y., Gao Y., Li G. P., Ren A. Z., Gao Y. B. (2016). Effect of different species of endophytes on fungal disease resistance of Achnatherum sibiricum. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 40 925–932. 10.17521/cjpe.2015.0417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D., Rajendran S. R. C. K., Gaur M., Sajeesh P., Kumar A. (2016). Plant defense signaling and responses against necrotrophic fungal pathogens. J. Plant Growth Regul. 35 1159–1174. 10.1007/s00344-016-9600-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pańka D., Jeske M., Troczyński M. (2011). Effect of Neotyphodium uncinatum endophyte on meadow fescue yielding, health status and ergovaline production in host-plants. J. Plant Protect. Res. 51 362–370. 10.2478/v10045-011-0059-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pańka D., Piesik D., Jeske M., Baturo C. A. (2013a). Production of phenolics and the emission of volatile organic compounds by perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.)/ Neotyphodium lolii association as a response to infection by Fusarium poae. J. Plant Physiol. 170 1010–1019. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pańka D., West C. P., Guerber C. A., Richardson M. D. (2013b). Susceptibility of tall fescue to Rhizoctonia zeae infection as affected by endophyte symbiosis. Ann. Appl. Biol. 163 257–268. 10.1111/aab.12051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perez L. I., Gundel P. E., Marrero H. J., Arzac A. G., Omacini M. (2017). Symbiosis with systemic fungal endophytes promotes host escape from vector-borne disease. Oecologia 184 237–245. 10.1007/s00442-017-3850-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect S. E., Green J. R. (2001). Infection structures of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungal plant pathogens. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2 101–108. 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski R. J., Powell R. G., Clay K. (1992). Alkaloids of Stipa robusta (sleepygrass) infected with an Acremonium endophyte. Nat. Toxins 1 84–88. 10.1002/nt.2620010205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre Y. D., Eaton C. J., Wargent J. J., Susanne F., Peter S., Jan S., et al. (2015). Fungal endophyte infection of ryegrass reprograms host metabolism and alters development. New Phytol. 208 1227–1240. 10.1111/nph.13614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Yan J., Li Y., Jiang H., Sun J., Chen Q., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis thaliana plants differentially modulate auxin biosynthesis and transport during defense responses to the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria brassicicola. New Phytol. 195 872–882. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Gao Y., Liu H., Zhou Y., Ren A., Gao Y. (2016). Effect of endophyte infection and clipping treatment on resistance and tolerance of Achnatherum sibiricum. Front. Microbiol. 7:1988. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren A. Z., Li X., Han R., Yin L. J., Wei M. Y., Gao Y. B. (2011). Benefits of a symbiotic association with endophytic fungi are subject to water and nutrient availability in Achnatherum sibiricum. Plant Soil 346 363–373. 10.1007/s11104-011-0824-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabzalian M. R., Mirlohi A., Sharifnabi B. (2012). Reaction to powdery mildew fungus, Blumeria graminis in endophyte-infected and endophyte-free tall and meadow fescues. Austral. Plant Pathol. 41 565–572. 10.1007/s13313-012-0147-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl C. L., Florea S., Pan J., Nagabhyru P., Bec S., Calie P. J. (2013). The epichloae: alkaloid diversity and roles in symbiosis with grasses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16 480–488. 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimanuki T., Sato T. (1983). Occurrence of the choke disease on timothy caused by Epichloë typhina (Pers. ex Fr.) Tul. in Hokkaido and location of the endophytic mycelia with plant tissue. Res. Bull. Hokkaido Nat. Agric. Exp. Stn. 183 87–97. 10.1002/j.1834-4461.1991.tb02382.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. R., Latch G. C. (1991). Expression of antifungal activity in agar culture by isolates of grass endophytes. Mycologia 83 529–537. 10.1080/00275514.1991.12026047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strange R. N., Scott P. R. (2005). Plant disease: a threat to global food security. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43 83–116. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.113004.133839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri P., Kakooee T. (2017). Reactive oxygen species accumulation and homeostasis are involved in plant immunity to an opportunistic fungal pathogen. J. Plant Physiol. 216 152–163. 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A., Takemoto D., Chujo T., Scott B. (2012). Fungal endophytes of grasses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15 462–468. 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A., Tapper B. A., Popay A., Parker E. J., Scott B. (2005). A symbiosis expressed non-ribosomal peptide synthetase from a mutualistic fungal endophyte of perennial ryegrass confers protection to the symbiotum from insect herbivory. Mol. Microbiol. 57 1036–1050. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma B. P., Eggermont K., Penninckx I. A., Mauch M. B., Vogelsang R., Cammue B. P., et al. (1998). Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 15107–15111. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevathan L. E. (1996). Performance of endophyte-free and endophyte infected tall fescue seedlings in soil infested with Cochliobolus sativus. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 18 415–418. 10.1080/07060669609500597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vos I. A., Pieterse C. M., Van W. S. C. (2013). Costs and benefits of hormone-regulated plant defences. Plant Pathol. 62 43–55. 10.1111/ppa.12105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wäli P. R., Helander M. O., Saikkonen K. (2006). Susceptibility of endophyte-infected grasses to winter pathogens (snow molds). Can. J. Bot. 84 1043–1051. 10.1139/B06-075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Qin J., Chen W., Zhou Y., Ren A., Gao Y. (2016). Pathogen resistant advantage of endophyte-infected over endophyte-free Leymus chinensis is strengthened by pre-drought treatment. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 144 477–486. 10.1007/s10658-015-0788-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. P., Cheng X., Shan Q. W., Zhang Y., Liu J. X., Gao C. X., et al. (2014). Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploidy bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 947–951. 10.1038/nbt.2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Hui D., Niu Y., Zhao X., Jie G. (2011). A survey of pathogenic fungi on four common gramineous weeds in northeastern China. Plant Protect. 37 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. K., Gao Y. B., Zhang X., Su D., Wang Y. H., Xu H., et al. (2007). Distribution and diversity of Epichloë/Neotyphodium fungal endophytes from different populations of Achnatherum sibiricum (Poaceae) in the Inner Mongolia Steppe, China. Fungal Divers. 24 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Welty R., Barker R., Azevedo M. (1993). Reaction of tall fescue infected and noninfected by Acremonium coenophialum to Puccinia graminis subsp. graminicola. Plant Dis. 75:883 10.1094/PD-75-0883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White R. (1979). Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) induces resistance to tobacco mosaic virus in tobacco. Virology 99 410–412. 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90019-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiewióra B., Żurek G., Żurek M. (2015). Endophyte-mediated disease resistance in wild populations of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Fungal Ecol. 15 1–8. 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C., Li N., Zhang Y., Li C., Zhang X., Nan Z. (2018). Role of Epichloë endophytes in defense responses of cool-season grasses to pathogens: a review. Plant Dis. 102 2061–2073. 10.1094/PDIS-05-18-0762-FE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C., Zhang X., Christensen M. J., Nan Z., Li C. (2015). Epichloë endophyte affects the ability of powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis) to colonise drunken horse grass (Achnatherum inebrians). Fungal Ecol. 16 26–33. 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Gao W. (2009). Effects of phenolic allelochemicals on the pathogen of Panax quiquefolium L. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 25 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yue F., Duan T., Cai Y., Cai S. (2019). Occurrence and prevention of grassland pests in China. Forest Pest Dis. 38 27–31. 10.19688/j.cnki.issn1671-0886.20190023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ren A., Wei Y., Lin F., Li C., Liu J., et al. (2009). Taxonomy, diversity and origins of symbiotic endophytes of Achnatherum sibiricum in the Inner Mongolia Steppe of China. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 301 12–20. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Li X., Liu H., Gao Y., Mace W. J., Card S. D., et al. (2019). Effects of endophyte infection on the competitive ability of Achnatherum sibiricum depend on endophyte species and nitrogen availability. J. Plant Ecol. 12 815–824. 10.1093/jpe/rtz017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.