Highlights

-

•

The clinical presentaion of early abdominal pregnancy is similar to that of tubal ectopic pregnancy in the majority of cases.

-

•

Surgical laparoscopy must be the first choice in management of early abdominal pregnancy.

-

•

Medical treatment should be reserved when a surgical intervention is deemed to be potentially very hemorrhagic.

Keywords: Abdominal, Pregnancy, Laparoscopy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Abdominal pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancies associated with a high mortality rate. Symptoms are not specific and usually resemble the other types of ectopic pregnancies. Medical management is used in cases where a potentially lethal hemorrhage can be anticipated. Nowadays, laparoscopic surgery has become the most common choice especially in cases diagnosed during the first trimester.

Presentation of case

A 35-year-old woman consulted for a pelvic pain and menstruation delay. She had a stable hemodynamic status and hypogastric tenderness during deep abdominal palpation. The βHCG rate was at 16041 IU/l. Pelvic ultrasonography revealed a gestational sac next to the right adnexa of 1.2 cm. Laparoscopic exploration was performed finding normal fallopian tubes and ovaries with a 2 cm mass on the vesical peritoneum. Resection of ectopic pregnancy was successfully performed and patient was discharged the next day with no postoperative complications.

Discussion

To date, there is no therapeutic protocol that has been established and there are no predictive criteria of success concerning medical management for ectopic pregnancy. Surgery is the most common choice in the therapeutic management of ectopic abdominal pregnancy. Laparotomy was preferred to the laparoscopic surgery because of the high risk of perioperative hemorrhage which can be uncontrollable from the implantation site. Nowadays, laparoscopic surgery should be the first measure if the abdominal pregnancy is diagnosed at an early stage (< 12 weeks) or if the implantation site allows a non-hemorrhagic surgical excision.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic management of abdominal pregnancies is an encouraging choice to laparotomy.

1. Introduction

Primary abdominal pregnancy occurs when the gestational sac attaches directly in the abdominal peritoneum. Most of cases, abdominal pregnancies are secondary, the most common mechanism is an implantation on the peritoneum after a tubal abortion. The abdominal pregnancy rates range between 1:10,000 and 1:30,000 in the population, and it represents 1% of extrauterine pregnancies [1]. Abdominal pregnancies are related to a high-risk of maternal morbidity and mortality [2]. The management of early form is based on surgery. Laparotomy is the most common type of surgery especially in hemorrhagic forms [3]. We report a case of primary abdominal pregnancy incidentally diagnosed at an early stage. The work has been reported in accordance with SCARE criteria [4].

2. Observation

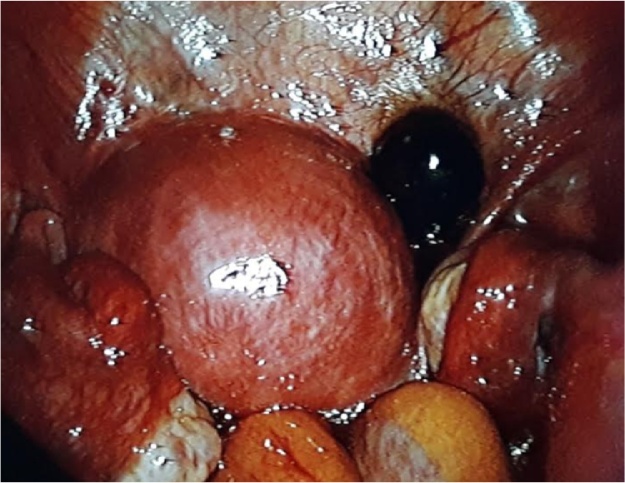

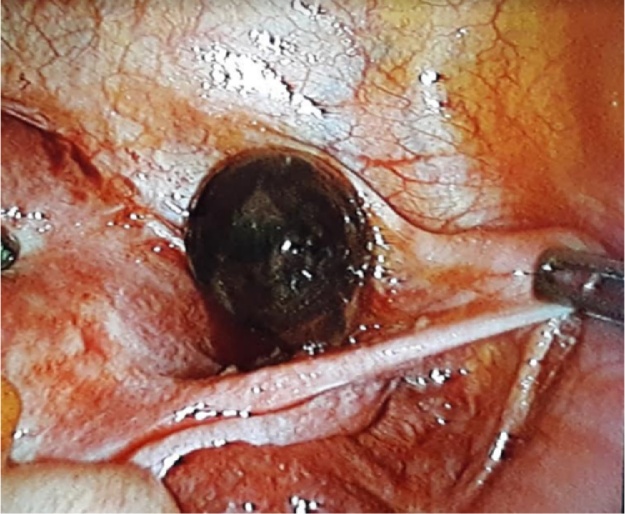

A 35-year-old woman, who is primigravida trying to get pregnant since 6 months. She was doing a follow-up for a myomatous uterus and did not have any particular surgical history. No contraception was used in the past. The patient presented on his one into Emergency room with a pelvic pain and late periods (5th week of amenorrhea.). No particular pharmacological history or family history were founded in anamnesis. During the examination, she was in good general condition. She had a stable hemodynamic status and hypogastric tenderness during deep abdominal palpation. Gynaecological examination showed a long closed posterior cervix with no macroscopic abnormalities and no bleeding. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed and revealed an empty uterus that was increased in size, a posterior leiomyoma measuring 4 cm, a gestational sac next to the right adnexa of 1.2 cm with no associated fluid in the pouch of Douglas (Fig. 1). The beta chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) rate was 16041 IU/l. Laparoscopy was performed immediately following conventional techniques: under general anaesthesia, using a 10 mm umbilical trocar and 3 trocars of 5 mm (2 lateral trocars and a median hypogastric trocar). The procedures assessment were a slight increase of the size of uterus with a posterior intramural leiomyoma of 4 cm, normal fallopian tubes and ovaries with a corpus luteum on the right and a 2 cm mass on the vesical peritoneum (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). We proceeded with a progressive excision and dissection of the peritoneum on which the ectopic sac was implanted using monopolar hook. Haemostasis was then ensured by a bipolar forceps. The surgical procedure was not hemorrhagic (blood loss was estimated at few milliliters) and no complications happened (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Frontal section of pelvic ultrasound (latero uterine masse related to extra uterine pregnancy).

Fig. 2.

Laparoscopic view showing a mass adhering to the vesical peritoneum with a strictly normal appearance of the tubes.

Fig. 3.

Laparoscopic view showing a mass adhering to the vesical peritoneum.

Fig. 4.

Laparoscopic view of pelvic (surgical site after excision of the ectopic sac and after achieving haemostasis).

The resection specimen was sent for an anatomopathological examination and the patient was discharged the next day and resumption of activity was authorized after 48 h. Contraception was not recommended. The patient was checked up 1 month later at the consultation with histopathology result which confirm the diagnosis. There was no complaint and physical examination was totally normal. The postoperative evolution was favorable where complications were noted.

3. Discussion

Abdominal pregnancy represents about 1% of extrauterine pregnancies with an incidence of 1:10.000–1:30.000 of all pregnancies [1]. The level of maternal mortality is estimated to be at 7.7 times that of other ectopic tubal pregnancies and is 90 times higher than intrauterine pregnancies. In a review of 5221 cases of abdominal pregnancy, Atrash HK showed that the mortality rate was 5.1 per 1000 cases, 54.5% of them were early abdominal pregnancies [2].

Multiple locations of ectopic abdominal pregnancies were reported, the most common ones were: recto-uterine and vesico-uterine pouchs (24.3%), uterine and tubal serosa (23.9%). No specific risk factors were particularly associated to abdominal pregnancy. Some authors have reported higher occurrences in countries with a low socioeconomic status due to the high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections causing tubes’ damage [4]. Other authors have reported abdominal pregnancy cases occurring after assisted reproductive technology [5].

The first classification of abdominal pregnancies divided them into 2 groups based on the physiopathological mechanism [6]

-

-

Primary abdominal pregnancies: this form is exceptional, the fertilized ovum implants directly on the peritoneal surface. The diagnosis is based on the following criteria defined by Studdiford: normal fallopian tubes and ovaries, absence of uteroperitoneal fistula, and pregnancy that is attached only to the peritoneal surface and is diagnosed early (less than 12 weeks of amenorrhea), excluding the possibility of secondary abdominal pregnancy. The implantation site is variable, it can be pelvic (rectouterine pouch, fundus or posterior side of the uterus), abdominal (diaphragm, liver, spleen, omentum) or even retroperitoneal.

-

-

Secondary abdominal pregnancy is the most common form. It can result from tubal rupture or from a tubo-abdominal abortion. It can also be the consequence of an intrauterine pregnancy after a rupture of a hysterotomy scar, or a uterine perforation or a rupture of a rudimentary horn.

This classification does not have any practical interest in opposition to the classification based on the pregnancy term. Therefore, we call early abdominal pregnancy when the term is less than 20 weeks of amenorrhea and advanced abdominal pregnancy when that limit exceeds 20 weeks [7].

The Diagnosis of an early abdominal pregnancy does not always seem to be obvious because during the first trimester, the clinical presentation is similar to that of tubal ectopic pregnancy in the majority of cases. Clinical, ultrasonographic and biological criteria do not always allow the clear diagnosis of an abdominal pregnancy and in most of the cases, the diagnosis is pronounced in the preoperative stage during a laparoscopy or a laparotomy performed following a suspicion of a tubal pregnancy. Pathological kinetics of serum βHCG allows to suggest the diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy but does not help to confirm the diagnosis of an abdominal pregnancy [7]. Although Ultrasound is the tool of choice, it does not always allow to distinguish an abdominal pregnancy from other types of extrauterine pregnancies. In only 50% of cases, ultrasound allows to pronounce the diagnosis of an early abdominal pregnancy. Ultrasonographic criteria were suggested for the diagnosis of an abdominal pregnancy [8]: fetus and a gestational sac observed outside the uterine cavity, or the visualisation of an abdominal or pelvic mass identifiable as an uterus and separated from the fetus, absence of the uterine wall between the bladder and the fetus, adherence of the fetus to an abdominal organ and abnormal location of placenta outside the uterine cavity.

Medical treatment of abdominal pregnancy has been reported by some authors [9]. This solution is suggested when a surgical intervention is deemed to be potentially very hemorrhagic especially in abdominal pregnancies with a hepatic or splenic location [7].

Patients should be closely monitored due to the possibility of a surgery in case of a hemorrhagic complication. No therapeutic protocol has been established and there are no predictive criteria of success concerning medical management [4]. The most common protocols in literature reviews are based on In situ or systemic methotrexate injection or in situ potassium chloride injection [5,10]. In a literature review published in 2012, among the nine patients diagnosed with an abdominal pregnancy located on the vesical serosa, only three received medical treatment at first and all the patients needed an adjuvant therapy (one case of embolisation and two cases of surgical resection) [4]. Other authors have reported deceiving results concerning methotrexate use in retroperitoneal abdominal pregnancies [9].

Surgery is the most common choice in the therapeutic management of ectopic abdominal pregnancy. Laparotomy was chosen to be better than laparoscopic surgery because of the risk of perioperative hemorrhage which can be uncontrollable from the implantation site [2].

The laparoscopic surgery is chosen instead of laparotomy if the abdominal pregnancy is diagnosed at an early age (< 12 weeks) or if the implantation site allows a non-hemorrhagic surgical excision. Peroperative haemostasis control is ensured by electrocoagulation using bipolar forceps. Shaw and al. have published multiple cases (1994–2005) on laparoscopic surgical management of ectopic abdominal pregnancies [10]. Global rate of laparoscopic surgery was 55%. The study has shown that with technologie progress and improving operator skills, the surgical management of abdominal pregnancies could be ensured by laparoscopy. The authors have reported significant reduction of blood loss and hospitalization.

4. Conclusion

Abdominal pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancies that can be potentially serious due to the hemorrhagic complications. The early diagnosis offers a better prognosis. However, clinical polymorphism makes early diagnosis difficult. Surgical laparoscopic management has been increasingly used in the previous years. It allows an initial diagnosis approach, an evaluation of the size and the exact location of the pregnancy. Therefore it offers a better view of the possibility of laparoscopic excision and the potential hemorrhagic complications.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Sources of funding

The study sponsors had no such involvement.

Ethical approval

The study is exempt from ethical approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Ahmed Hajji: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft.

Dhekra Toumi: Writing - Original Draft, Visualization.

Ons Laakom: Writing - Original Draft.

Ons Cherif: Supervision.

Raja Faleh: Writing - Review & Editing.

Registration of research studies

NA.

Guarantor

Ahmed Hajji.

Raja Faleh.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Yoder N., Tal R., Martin J.R. Abdominal ectopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and single embryo transfer: a case report and systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2016;14:69. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0201-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atrash H.K., Friede A., Hogue C.J. Abdominal pregnancy in the United States: frequency and maternal mortality. Obstet. Gynecol. 1987;69:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cristalli B., Guichaoua H., Heid M., Izard V., Levardon M. Grossesse ectopique abdominale. Limites du traitement cœlioscopique. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 1992;21:751–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaron P., David H., Everett F.M. Early abdominal ectopic pregnancies: a systematic review of the literature. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2012;74:249–260. doi: 10.1159/000342997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferland R.J., Chadwick D.A., O’Brien J.A., Granai C.O. An ectopic pregnancy in the upper retroperitoneum following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;78:544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beacham W.D., Hernquist W.C., Beacham W.D., Webster H.D. Abdominal pregnancy; discussion, classification, and case presentation. Obstet. Gynecol. 1954;4(Oct. (4)):435–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilesh A., Funlayo O. Early abdominal ectopic pregnancy: challenges, update and review of current management. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;16:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allibone G.W., Fagan C.J., Porter S.C. The sonographic features of intra-abdominal pregnancy. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 1981;9:383–387. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870090706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okorie C.O. Retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy: is there any place for non-surgical treatment with methotrexate? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2010;36:1133–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]