Abstract

Objectives

The manipulation of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is associated with differential mortality and neurological injury in intensive care and cardiac arrest patients, however few studies have investigated this relationship in patients on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO). We investigated the association between the initial PaCO2 and change over 24 hours, on mortality and neurological injury in patients undergoing VA ECMO for cardiac arrest and refractory cardiogenic shock.

Design

Retrospective cohort analysis of adult patients recorded in the international Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry.

Setting

Data reported to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization from all international extracorporeal membrane oxygenation centers during 2003–2016.

Patients

Adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) supported with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

7168 patients had sufficient data for analysis at initiation of VA ECMO, 4918 of these had PaCO2 data available at 24 hours on support. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 59.9%. A U-shaped relationship between PaCO2 tension at ECMO initiation and in-hospital mortality was observed. Increased mortality was observed with a PaCO2 tension less than 30 mmHg (odds ratio [OR], 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08 – 1.47, p=0.003) and greater than 60 mmHg; OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10 – 1.50; (p=0.002). Large reductions (greater than 20 mmHg) in PaCO2 over 24 hours were associated with important neurological complications: intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke and/or brain death, as a composite outcome (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.03 – 2.59, p=0.04), independent of the initial PaCO2.

Conclusions

Initial PaCO2 tension were independently associated with mortality in this cohort of VA ECMO patients. Reductions in PaCO2 (>20 mmHg) from initiation of ECMO were associated with neurologic complications. Further prospective studies testing these associations are warranted.

Keywords: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO, carbon dioxide, ELSO, Neurological complications

Introduction

Circulatory failure and cardiac arrest result in inadequate tissue perfusion and widespread ischemic injury (1). Interventions such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) have tended to focus on the maintenance of oxygenation and perfusion pressures. In comparison, there has been relatively little systematic investigation concerning the role of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2). PaCO2 is known to have significant biological effects on vascular tone, organ perfusion and outcomes, however the optimal PaCO2 for brain and systemic perfusion in patients with circulatory failure is unknown (2).

Hypocarbia (PaCO2 <35mmHg) on the one hand can cause vasoconstriction and ischemic injury. In traumatic brain injury, hyperventilation for this reason, is no longer recommended in the first 24 hours (3). Hypercarbia (PaCO2 >50mmHg) on the other hand is associated with worse outcomes compared to normocarbia in general ICU patients (4). However, there may be a subset of patients who might derive benefit from deliberate mild hypercarbia (5). A recent large observational study of cardiac arrest patients found mild hypercarbia to be associated with an increased probability of discharge home (6). Vasodilatation with hypercarbia (7) leading to improved cerebral perfusion (8) is thought to be the underlying mechanism (9). Other physiological benefits from CO2 such as anti-convulsive, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects may play an additional role (7, 10). As such, mild hypercarbia is currently being investigated as a therapeutic target to improve outcomes in cardiac arrest patients (11, 12). To date, patients on ECMO have generally been excluded from these analyses (6, 13, 14).

In venoarterial (VA) ECMO PaCO2 is regulated by adjusting the fresh gas flow to the oxygenator (15). Interestingly, the relationship of PaCO2 with cerebral perfusion may be altered whilst on ECMO through impaired autoregulation and generally lower cerebral blood flow but data is limited (16, 17). More recently CO2 has more directly been implicated in neurological complications and outcomes (17–21). Given the wide range of potential PaCO2 tensions that can generally be achieved by regulating the fresh gas flow (15, 22) PaCO2 would represent an attractive target to potentially improve organ perfusion and outcomes.

The aims of this study were to investigate the relationship between the initial PaCO2 and change over the first 24 hours after initiation of ECMO, and mortality and neurological outcomes, in a large cohort of VA ECMO patients in the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) international registry. Our primary hypothesis was that moderate hypocarbia would be associated with differential in-hospital mortality in patients receiving VA ECMO.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a retrospective study of all adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) supported with VA ECMO entered into the international ELSO registry. The study was supported by a research grant from ELSO (request # 1980) and approved by The Alfred Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (project number 488–17, Melbourne, Australia), with a waiver of individual patient consent.

De-identified data was extracted from 2003–2016. Only the first ECMO run was analyzed in the case of multiple runs. Patients were excluded if initial PaCO2 levels were unavailable, if PaCO2 readings were >200 or <15 mmHg (levels possibly related to non-conversion from kPa units or representing PaO2) or where a primary diagnosis was not recorded. Variables included patient demographic data, details about the ECMO run including year and timing of initiation, diagnostic codes according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-09 and ICD-10), as well as hospital outcome. Further pre-ECMO variables included: vital parameters, blood gases, ventilator settings, and diagnosed organ failure. Diagnoses were grouped into acute myocardial infarction, aortic disease, congenital heart disease, fulminant myocarditis, post-transplantation, pulmonary embolism, refractory ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation, sepsis, valvular heart disease, chronic heart disease and other post-operative diagnoses as previously described (23).

PaCO2 tensions in the ELSO database

Initial PaCO2 tension refers to a pre-ECMO arterial blood gas closest to the time of ECMO initiation but not more than 6 hours before. The 24-hour value is indicative of the blood gas closest to 24 hours but not more than 6 hours before or beyond the 24-hour mark.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was mortality at hospital discharge. We also examined the development of neurological complications (brain death, ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage, as defined as per the ELSO dataset) as a composite secondary outcome.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed with STATA 14.2 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP). Patients were grouped into 5 categories according to the PaCO2 prior to initiation of ECMO and at 24-hours; less than 30 mmHg (moderate hypocarbia), 30–34 mmHg (mild hypocarbia), 35–44 mmHg (normal reference range), 45–59 mmHg (mild hypercarbia), and 60mmHg or greater (moderate hypercarbia). These thresholds were chosen as there is no consistent definition for mild, moderate, or severe hypo/hypercarbia, and these cut-points roughly represent the inflection points of the sigmoid relationship between PaCO2 and cerebral blood flow (24). For the change in PaCO2 over 24 hours, five categories were generated approximating quintiles with rounded cut-offs to achieve similar sized groups. Results are reported as mean +/− standard deviation for continuous, normally distributed data, median (interquartile range) for continuous non-parametric data or percent (number) for categorical data. Comparisons between survivors and non-survivors were conducted with student’s t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test or χ2 tests as appropriate for each type of data.

Severity of illness prior to ECMO was assessed using the SAVE score (23). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was undertaken to determine the relationship between initial Pa CO2 and outcome, adjusting for severity of illness prior to ECMO; using the SAVE score (23) and support type (VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock or ECMO-cardiopulmonary resuscitation). To determine the relationship between outcomes and the change in PaCO2 over the first 24hours, initial PaCO2 category was further added as an independent variable to the regression. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and comparison of survivors and non-survivors

11726 patients were identified in the database and 423 were excluded for multiple ECMO runs. A further 3367 patients were excluded for missing initial PaCO2 tensions, 397 for implausible PaCO2 readings, and a further 371 who did not have a primary diagnosis. This left 7168 patients who formed the study population. PaCO2 at 24 hours was reported for 4918 patients. Survivors were younger, had less days in the intensive care unit prior to the initiation of ECMO, had a shorter duration on ECMO, and more commonly were diagnosed with myocarditis or post heart or lung transplantation. Diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction, aortic disease, congenital heart disease or other acute organ failures were more common in non-survivors. Non-survivors also had lower systemic blood pressures, higher peak ventilator pressures and lower oxygen saturations prior to ECMO (Table 1). A comparison of included and excluded populations based on initial CO2 demonstrated shorter times to ECMO and more frequent prior cardiac arrest in the excluded patients but no difference in SAVE score or mortality (Supplementary Table1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Study Population and Univariate Analysis Between Survivors and Non-survivors

| Characteristics | Total (n=7168) | Dead in hospital (n=4293) | Alive at hospital discharge (n=2875) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 53.3 (16.0) | 54.9 (15.9) | 51.0 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 4806 (67.5) | 2876 (67.5) | 1930 (67.6) | 0.89 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 81.2 (22.6) | 81.9 (23.5) | 80.2 (21.2) | 0.002 |

| Details of ECMO run | ||||

| Interval ICU admission-ECMO, h, median, (IQR) | 24 (5–109) | 27 (6–122) | 20 (5–85) | <0.001 |

| Ventilation prior to ECMO, h, median, (IQR) | 9 (2–24) | 9 (2–26) | 8 (2–20) | <0.001 |

| Duration of ECMO support, h, median, (IQR) | 96 (47–169) | 89 (35–173) | 105 (64–165) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ECMO support | ||||

| Cardiac arrest prior to ECMO, n (%) | 2804 (39.2) | 1828 (42.6) | 976 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 2038 (28.4) | 1215 (28.3) | 823 (28.6) | 0.77 |

| Vasopressor/ inotropic support, n (%) | 4120 (57.5) | 2548 (59.4) | 1572 (54.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 350 (4.9) | 252 (5.9) | 98 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Diagnoses associated with cardiogenic shock | ||||

| Acute myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1563 (21.8) | 986 (23.0) | 577 (20.0) | 0.004 |

| Aortic disease, n (%) | 251 (3.5) | 182 (4.2) | 69 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 540 (7.5) | 351 (8.2) | 189 (6.6) | 0.01 |

| Myocarditis, n (%) | 236 (3.3) | 103 (2.4) | 133 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Post heart or lung transplantation, n (%) | 345 (4.8) | 249 (3.5) | 196 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 305 (4.3) | 175 (4.1) | 130 (4.5) | 0.36 |

| Refractory ventricular arrhythmias VT/VF, n (%) | 583 (8.1) | 351 (8.2) | 232 (8.1) | 0.87 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 522 (7.3) | 367 (8.6) | 155 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 976 (13.6) | 591 (13.8) | 385 (13.4) | 0.65 |

| Chronic heart failure of other causes, n (%) | 2020 (28.2) | 1229 (28.6) | 791 (27.5) | 0.3 |

| Other post-operative diagnoses, n (%) | 95 (1.3) | 64 (1.5) | 31 (1.1) | 0.13 |

| Others acute pre-ECMO organ failure | ||||

| Liver failure, n (%) | 45 (0.6) | 32 (0.8) | 13 (0.5) | 0.12 |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 1533 (21.4) | 950 (22.1) | 583 (20.3) | 0.06 |

| Central nervous system dysfunction, n (%) | 487 (6.8) | 361 (8.4) | 126 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 1216 (17.0) | 849 (19.8) | 367 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ECMO blood pressure and ventilator settings | ||||

| Systolic pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 80.8 (27.3) | 79.2 (27.5) | 83.2 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 49.3 (17.5) | 47.7 (17.4) | 51.5 (17.3) | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 30 (20–41) | 29 (19–41) | 30 (20–40) | 0.20 |

| PIP, cmH2O, mean (SD) | 24.6 (6.9) | 25.4 (7.3) | 23.5 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| PEEP, cmH2O, median (SD) | 7.5 (5–10) | 7.5 (5–10) | 8 (5–10) | 0.29 |

| Pre-ECMO blood gas | ||||

| PaCO2, mmHg, mean (SD) | 45.5 (19.6) | 46.5 (20.6) | 44.1 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| PaO2, mmHg, median (IQR) | 89 (60–182) | 86 (58–172) | 95 (63–200) | <0.001 |

| HCO3, mmol/L , median (IQR) | 19.4 (16–23) | 19 (15–23) | 20 (17–23) | <0.001 |

| SaO2, %, mean (SD) | 88.7 (16.7) | 87.3 (18.2) | 90.7 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| 24 hour ECMO blood gas (n=4918) | ||||

| PaCO2, mmHg, mean (SD) | 37.4 (8.5) | 37.4 (7.6) | 37.4 (9.1) | 0.74 |

| PaCO2 reduction in 24 hours, mmHg, mean (SD) | 8.1 (19.2) | 8.6 (19.8) | 7.2 (28.2) | 0.004 |

IQR = interquartile range

Overall, initial PaCO2 levels were higher in non-survivors versus survivors (46.5 vs 44.1 mmHg, p <0.001). At 24 hours there was no difference in PaCO2 levels between survivors and non-survivors (Table 1). Non-survivors had a greater reduction in PaCO2 between initiation and 24 hours.

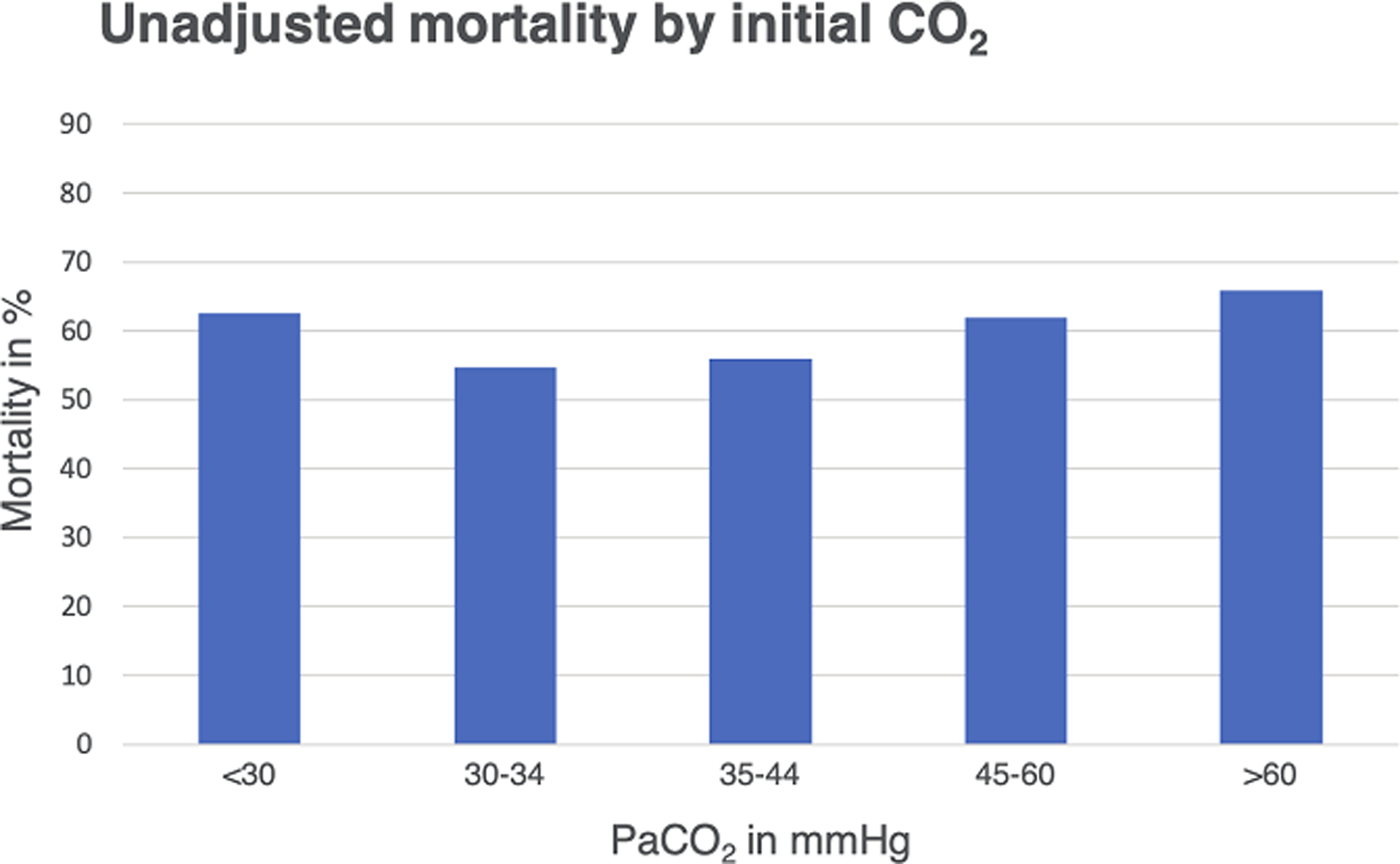

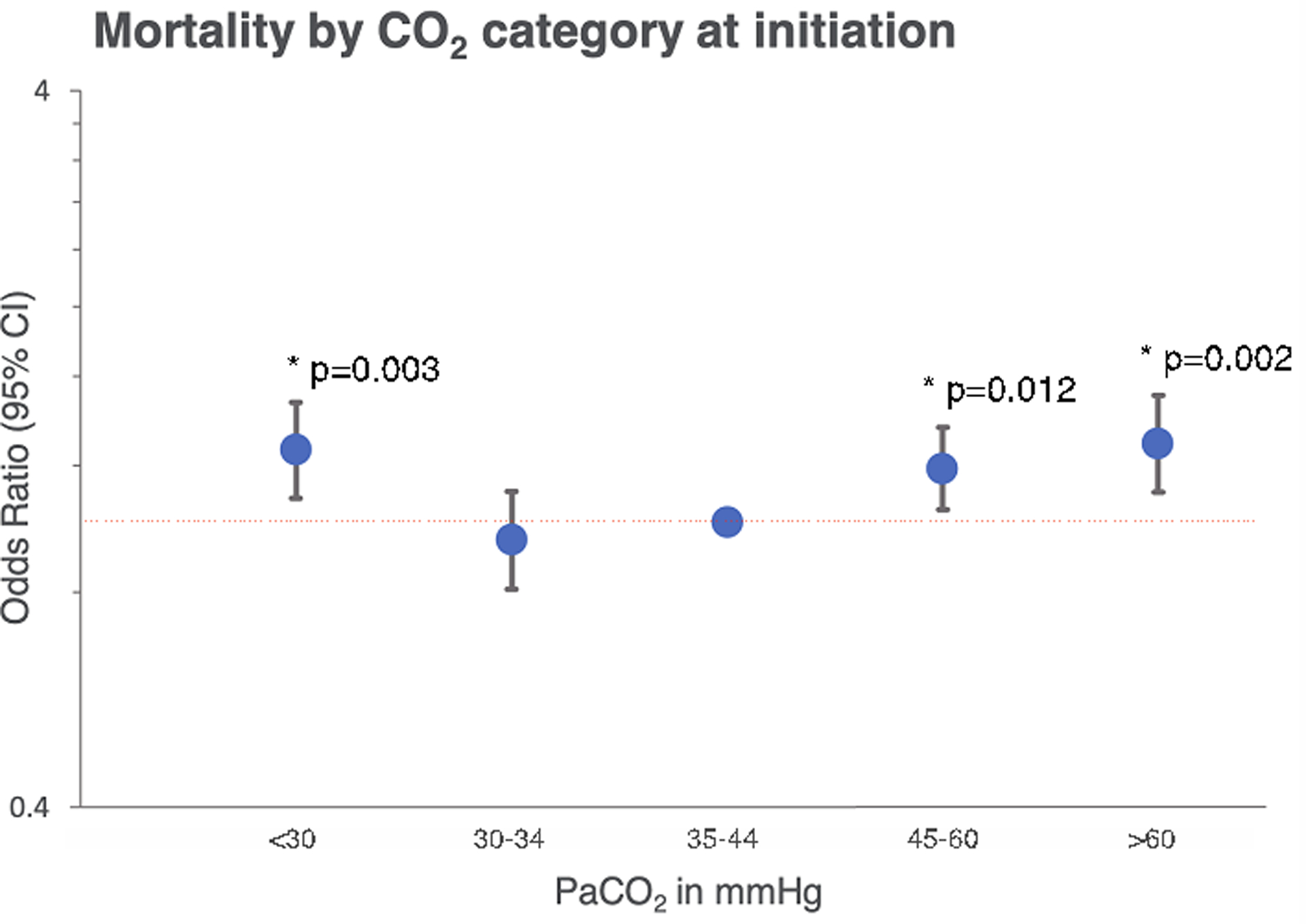

Hospital mortality and PaCO2

Overall in-hospital mortality rate was 59.9%. A “U” shaped relationship was observed, with mortality over 60% in patients with a PaCO2 less than 30mmHg and over 45mmHg at initiation of ECMO (Figure 1). After adjusting for confounders, there was a higher risk of mortality at both extremes of PaCO2 at initiation of ECMO; moderate hypocarbia (<30 mmHg) OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.08 – 1.47; (p=0.003) and moderate hypercarbia (>60 mmHg) OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10 – 1.50; (p=0.002) (see Figure 2). Adjusted sub-group analyses of patients support for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) and refractory cardiogenic shock (non ECPR) are provided in the appendix (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Variations of unadjusted mortality according to the initial PaCO2 category are shown.

Figure 2.

Hospital mortality in relation to the initial pre-ECMO PaCO2 category is shown. Data is adjusted for SAVE score and support type+ and displayed on a logarithmic scale in reference to patients with normocarbia (odds ratio, 1; red dotted line). Differences in mortality with P values <0.05 are displayed (*). Complete data can be found in Supplemental Table 2. +Support type differentiates VA ECMO for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and refractory cardiogenic shock.

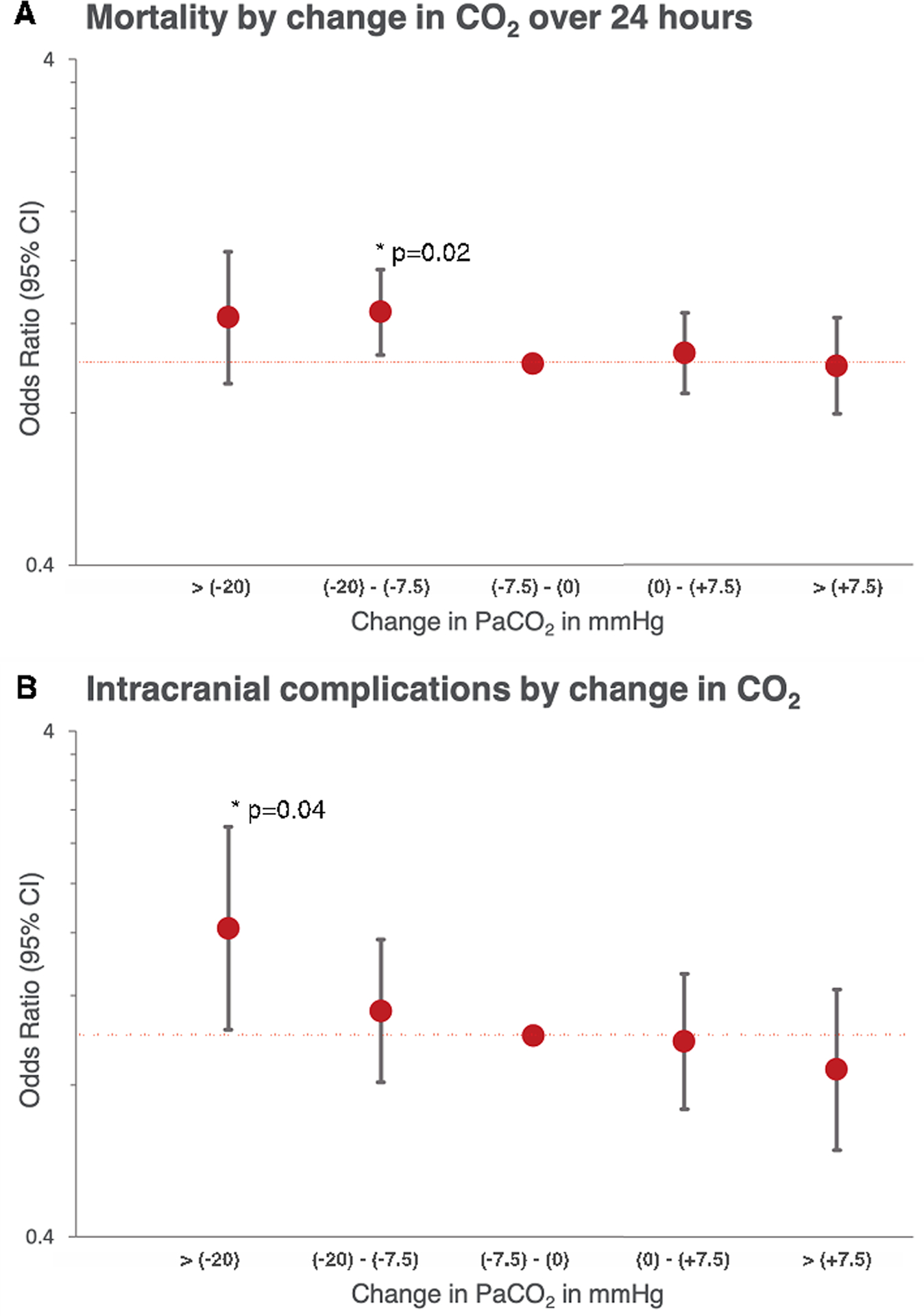

At 24 hours, only moderate hypocarbia (<30 mmHg) remained significantly associated with increased mortality (Supplementary Figure 2). Analyzing the change in PaCO2 over the first 24 hours, larger reductions in PaCO2, tended to be associated with higher mortality, independent of the initial PaCO2 level. This was significant for reductions in PaCO2 of 7.5 – 20 mmHg; OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.04 – 1.54, p=0.02 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Displayed is (A) adjusted mortality and (B) intracranial complications (intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke and brain death) in similar sized groups stratified by the absolute change in PaCO2 from pre-initiation of ECMO to 24 hours on support. Displayed is the odds ratio and 95% CI for mortality and neurologic complications, both adjusted for SAVE score, support type+ and initial PaCO2. P values <0.05 are displayed (*). Complete data in Supplemental Table 3. +Support type differentiates VA ECMO for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and all other VA ECMO.

Neurological complications

Table 2. shows observed incidence of important neurological complications: intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke and brain death according to each category of change in PaCO2. The percentages of ischemic stroke and brain death were highest with reductions of more than 20 mmHg in PaCO2. Adjusting for confounders, a reduction in PaCO2 of more than 20 mmHg was significantly associated with worse neurological outcomes; OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.03 – 2.59, p=0.04 (Figure 3). This was independent of the initial PaCO2.

TABLE 2.

Number of neurological complications on VA ECMO by category of change in PaCO2

| > (−20) n=910 |

(−20) - (−7.5) n=1146 |

(−7.5) - (0) n=1041 |

(0) - (+7.5) n=1036 |

> (+7.5) n=801 |

Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracranial hemorrhage, n (%) | 25 (2.8) | 26 (2.3) | 21 (2.0) | 29 (2.8) | 34 (4.2) | 0.45 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 62 (6.8) | 55 (4.9) | 44 (4.2) | 43 (4.2) | 32 (4.0) | 0.02 |

| Brain death, n (%) | 79 (8.8) | 43 (3.8) | 37 (3.6) | 40 (3.9) | 23 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Combined neurological complications, n (%) | 150 (16.6) | 110 (9.7) | 93 (8.9) | 97 (9.4) | 74 (9.2) | <0.001 |

Multiple complications may be present in individual patient hence combined numbers less than the sum of the complications

Discussion

Key findings

This study has identified a U-shaped relationship between initial PaCO2 before the initiation of VA ECMO and in-hospital mortality. Greater reductions in PaCO2 levels over the first 24 hours of ECMO support were also associated with increased mortality. Moreover, a large decrease in PaCO2 over the first 24 hours correlated with a greater risk of neurological complications.

Relationship to previous studies

Multiple previous studies have investigated the relationship between PaCO2 and mortality in critically ill patients. Helmerhorst et al. (14) and Roberts et al. (25) found U-shaped relationships between hospital mortality (14), poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge (25) and PaCO2 in cardiac arrest populations. The nadir was in the normal range for PaCO2 (35–45 mmHg) and was around 43 mmHg in the study by Helmerhorst. Schneider et al (6) also demonstrated a U-shaped relationship between in-hospital mortality and PaCO2 levels in a large cardiac arrest population of 16542 consecutive patients. Similar to our study, the association with mortality was stronger with hypocarbia than with elevated PaCO2. Indeed, this has substantial biological plausibility, given the established relationship between PaCO2, and cerebrovascular tone, such that moderate hypocarbia is associated with cerebral vasoconstriction and reduced cerebral blood flow, which may worsen ischemic injury (26).

Previous dedicated ECMO studies that have investigated the relationship between PaCO2 and mortality have demonstrated conflicting results. In an unadjusted analysis of the ELSO database, Munshi et al (18) did not show any relationship between respiratory alkalosis or acidosis and mortality in venovenous (VV) or VA ECMO patients. In contrast, in a small pediatric population of VV ECMO patients, a change in PaCO2 >25 mmHg was associated with greater mortality (21).

The association between PaCO2 and neurologic complications in ECMO has only been investigated in a few small retrospective studies. In a single center study of VA ECMO patients, the rate of change in PaCO2 from ‘before-to-after’ ECMO was associated with intracranial bleeding and mortality (20). In a small VV ECMO study by Luyt et al. (19), a decrease in CO2 by more than 27 mmHg was found to be associated with brain hemorrhage. Neurological complications are twice as common in VA ECMO than in VV ECMO (27), yet an incidence of 7.1% in VV ECMO (28) may also in part be an effect of changes in CO2. In addition, specific subgroups of patients (e.g. VA ECMO for cardiac arrest), may be particularly vulnerable to neurological injury with changes in PaCO2, although our findings were independent of the type of support provided. Overall these findings support a clinically relevant influence of PaCO2 on brain perfusion.

CO2 as a potential therapeutic target has recently been evaluated in the CCC pilot RCT (12) and is part of an ongoing multinational randomized controlled trial (11). This pilot study (excluding ECMO patients) randomized 83 post cardiac arrest patients to either 24 hours of mild hypercarbia (PaCO2 50 – 55mmHg) or normocarbia. Mild hypercarbia was associated with lower levels of neuron specific enolase, a surrogate marker for neurological injury (29). It is interesting to note that whilst hypercarbia was not associated with a survival benefit at 24 hours in our data, a large reduction in CO2 tensions did increase neurological injury. This may support the hypothesis that avoiding a large reduction in CO2 levels post cardiac arrest may be protective, although further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Strengths and Limitations

This study analyzed the largest currently available dataset regarding the associations between PaCO2 and in-hospital mortality in VA ECMO patients. Its findings build on prior research in non ECMO patients and are consistent with previous physiological studies.

This study however is limited by its retrospective nature, and it remains to be determined whether these associations are mere reflections of the pathophysiological state in circulatory failure or whether abnormal PaCO2 levels or their change are promoters of secondary injury and mortality. Other, non-measured factors, may in fact be driving this relationship, including the duration of cardiac arrest/ cardiogenic shock with metabolic derangement, inadequate ventilation or poor CPR performance. Other limitations include; 1) PaCO2 levels were missing in a quarter of the patients. 2) The exact timing of the PaCO2 level was not known, and no contextual data e.g. the duration of cardiac arrest or ventilation strategy was available. 3) 2250 patients could not be included in the multivariable analysis as data at 24 hours were missing 4) The effects of other therapies and site-based variation in practice on outcomes are unknown. 5) The ELSO data base is limited by voluntary data entry by member sites and does not capture ECMO outside of ELSO centers.

Implications

The U-shaped relationship with PaCO2 and mortality suggests that there may be a “physiological sweet spot” for PaCO2, and large decreases over 24 hours are associated with worse outcomes. It is not clear if manipulation of PaCO2 in the first 24 hours will result in improved hospital survival, however further studies should investigate this, particularly given CO2 can be safely and relatively easily manipulated in VA-ECMO patients. Although we would caution against wide reaching conclusions from our analyses, closely monitoring PaCO2 tensions post initiation of VA ECMO and aiming for gradual transition to normocarbia, would seem a prudent strategy. Of note, this is similar to previous conclusions in cardiac arrest populations (30, 31).

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that an abnormal initial PaCO2 was independently associated with increased mortality in a cohort of VA ECMO patients. Moreover, large reductions in PaCO2 over 24 hours were associated with neurological complications, correlating with the known physiologic effects of PaCO2 on brain perfusion. Future research regarding the optimal rate of change of PaCO2 once established on ECMO as well as prospective data from cardiac arrest patients will further inform about potential therapeutic PaCO2 targets in VA ECMO.

Supplementary Material

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

The study was supported by a research grant from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) request (# 1980). Dr R. Barbaro discloses to be the ELSO Registry Chair. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, et al. : Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation 2008; 118:2452–2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marhong J, Fan E: Carbon dioxide in the critically ill: too much or too little of a good thing? Respir Care 2014; 59:1597–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, et al. : Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 2017; 80:6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiruvoipati R, Pilcher D, Buscher H, et al. : Effects of Hypercapnia and Hypercapnic Acidosis on Hospital Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:e649–e656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kregenow DA, Rubenfeld GD, Hudson LD, et al. : Hypercapnic acidosis and mortality in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider AG, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R, et al. : Arterial carbon dioxide tension and outcome in patients admitted to the intensive care unit after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2013; 84:927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curley G, Laffey JG, Kavanagh BP: Bench-to-bedside review: carbon dioxide. Crit Care Lond Engl 2010; 14:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brian JE: Carbon dioxide and the cerebral circulation. Anesthesiology 1998; 88:1365–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eastwood GM, Young PJ, Bellomo R: The impact of oxygen and carbon dioxide management on outcome after cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014; 20:266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolner EA, Hochman DW, Hassinen P, et al. : Five percent CO₂ is a potent, fast-acting inhalation anticonvulsant. Epilepsia 2011; 52:104–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parke RL, McGuinness S, Eastwood GM, et al. : Co-enrolment for the TAME and TTM-2 trials: the cerebral option. Crit Care Resusc J Australas Acad Crit Care Med 2017; 19:99–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eastwood GM, Schneider AG, Suzuki S, et al. : Targeted therapeutic mild hypercapnia after cardiac arrest: A phase II multi-centre randomised controlled trial (the CCC trial). Resuscitation 2016; 104:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaahersalo J, Bendel S, Reinikainen M, et al. : Arterial blood gas tensions after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: associations with long-term neurologic outcome. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:1463–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmerhorst HJF, Roos-Blom M-J, van Westerloo DJ, et al. : Associations of arterial carbon dioxide and arterial oxygen concentrations with hospital mortality after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Lond Engl 2015; 19:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett R, Conrad S: The Physiology of Extracorporeal Life Support, Chapter 4. In: Brogan TV, Lequier L, Lorusso R, et al. , editor(s). . Ann Arbor: Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation; 2017. p. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien NF, Hall MW: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and cerebral blood flow velocity in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc 2013; 14:e126–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cashen K, Reeder R, Dalton HJ, et al. : Hyperoxia and Hypocapnia During Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Associations With Complications, Mortality, and Functional Status Among Survivors. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc 2018; 19:245–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munshi L, Kiss A, Cypel M, et al. : Oxygen Thresholds and Mortality During Extracorporeal Life Support in Adult Patients. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:1997–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luyt C-E, Bréchot N, Demondion P, et al. : Brain injury during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42:897–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Guennec L, Cholet C, Huang F, et al. : Ischemic and hemorrhagic brain injury during venoarterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care 2018; 8:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bembea MM, Lee R, Masten D, et al. : Magnitude of arterial carbon dioxide change at initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support is associated with survival. J Extra Corpor Technol 2013; 45:26–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toomasian J, Vercaemst L, Bottrell S, et al. : The Circuit, Chapter 5 In: Brogan TV, Lequier L, Lorusso R, et al., editor(s). Extracorporeal Life Support: The ELSO Red Book 5th Edition Ann Arbor: Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation; 2017. p. 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, et al. : Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordström C-H, Koskinen L-O, Olivecrona M: Aspects on the Physiological and Biochemical Foundations of Neurocritical Care. Front Neurol 2017; 8:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts BW, Kilgannon JH, Chansky ME, et al. : Association between postresuscitation partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide and neurological outcome in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. Circulation 2013; 127:2107–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts BW, Karagiannis P, Coletta M, et al. : Effects of PaCO2 derangements on clinical outcomes after cerebral injury: A systematic review. Resuscitation 2015; 91:32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorusso R: Extracorporeal life support and neurologic complications: still a long way to go. J Thorac Dis 2017; 9:E954–E956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O, et al. : Neurologic Injury in Adults Supported With Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure: Findings From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Database. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:1389–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronberg T, Rundgren M, Westhall E, et al. : Neuron-specific enolase correlates with other prognostic markers after cardiac arrest. Neurology 2011; 77:623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, et al. : European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine 2015 guidelines for post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41:2039–2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie N, Williams TA, Tohira H, et al. : A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between arterial carbon dioxide tension and outcomes after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2017; 111:116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.