Abstract

The World Health Organization (WHO) undertook the development of a rapid guide on the use of chest imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19. The rapid guide was developed over two months using standard WHO processes, except for the use of ‘rapid reviews’ and online meetings of the panel. The evidence review was supplemented by a survey of stakeholders regarding their views on the acceptability, feasibility, impact on equity and resource use of the relevant chest imaging modalities (chest radiography, chest CT and lung ultrasound). The guideline development group had broad expertise and country representation. The rapid guide includes three diagnosis recommendations and four management recommendations. The recommendations cover patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 with different levels of disease severity, throughout the care pathway from outpatient facility or hospital entry, to home discharge. All recommendations are conditional and are based on low certainty evidence (n=2), very low certainty evidence (n=2), or expert opinion (n=3). The remarks accompanying the recommendations suggest which patients are likely to benefit from chest imaging and what factors should be considered when choosing the specific imaging modality. The guidance also offers considerations about implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and identifies research needs.

Summary

The guide includes seven recommendations covering patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 with different levels of disease severity, throughout the care pathway from outpatient facility or hospital entry, to home discharge.

Key Results

■ The rapid guide includes three diagnosis recommendations and four management recommendations covering patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 with different levels of disease severity, throughout the care pathway from outpatient facility or hospital entry, to home discharge.

■ The rapid guide offers considerations about implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and identifies research needs.

■ The guide will be relevant for clinicians, hospital managers and planners, policy-makers, hospital architects, biomedical engineers, medical physicists, logistics staff, and control officers involved in water/sanitation and infection prevention.

Introduction

A cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China was first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) Country Office in China on 31st of December 2019 [1]. Soon thereafter, a novel coronavirus was identified as the causative agent [2-4]. This virus was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the associated disease was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [5]. Since December 2019, COVID-19 has rapidly spread from Wuhan to other parts of China and throughout the world. On 30 January 2020, WHO declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern and on 11 March 2020, WHO characterized the outbreak as a pandemic [6,7].

The diagnosis of COVID-19 is currently confirmed by identification of viral RNA in reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Chest imaging has been considered as part of the diagnostic workup of symptomatic subjects with suspected COVID-19 in settings where laboratory testing (RT-PCR) is not available or results are delayed or are initially negative in the presence of symptoms attributable to COVID-19.

COVID-19 manifests with non-respiratory symptoms as well as respiratory symptoms which are non-specific and of variable severity, ranging from mild to life threatening, which may demand advanced respiratory assistance and artificial ventilation. Imaging has been also considered to complement clinical evaluation and laboratory parameters in the management of patients already diagnosed with COVID-19 (1).

A recent international survey conducted by the International Society of Radiology and the European Society of Radiology found important variations in imaging practices related to COVID-19 [8]. Several countries requested WHO’s advice on the role of chest imaging in the diagnostic workup of subjects with suspected or probable COVID-19 disease and in the clinical management of patients with confirmed COVID-19. As a consequence, WHO undertook the development of a rapid guide on the use of chest imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19 [9].

Methods

The development of this rapid advice guide followed the process outlined in the WHO handbook for guideline development [10], which used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology [11]. Given the nature of the emergency, the process was implemented within a time frame of two months. The reporting of this guide followed the Reporting Items for practice Guidelines in HealThcare (RIGHT) checklist [12]. The main target audience of the guidance are health professionals involved in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19.

Group composition

In conformity with the WHO process, the following bodies were established: a core group (coordination role), a steering group (advisory role), a guideline development group (GDG; the expert panel) and an external review group (peer review role). Membership of the GDG and the external review group included experts from 10 high income countries and 14 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In addition, a systematic review team was contracted to conduct a rapid systematic review for each of the guidance’s questions. Appendix E1 provides the details on group composition and roles and list of contributors.

Management of declaration of interests

All experts declared their interests prior to participation in the guideline development processes and meetings. All declarations were managed following WHO regulations, on a case-by-case basis and communicated to the experts at the start of the first GDG meeting. A summary was included in Appendix E2. All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at ww.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no conflicts.

Identification of the key questions

The core group reviewed formal consensus statements from professional bodies and/or national health authorities on the use of chest imaging in COVID-19, with the assistance of the GDG and the International Society of Radiology. Informed by these statements [8,13], the core group formulated the key questions using the PICO format (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes), with the help of the steering group, the GDG and the systematic review team (see Appendix E3). The intended populations are those in whom a COVID-19 diagnosis need to be established and those in whom the diagnosis is already established. The questions addressed three chest imaging modalities (chest radiography, chest computed tomography [CT] and lung ultrasound); three questions addressed diagnosis while four questions addressed management. These key questions formed the basis of the systematic reviews and of the development of recommendations.

Identification of the critical outcomes

The core group drafted a list of outcomes relevant for each PICO question which was circulated to the GDG for importance rating [14]. The list included three types of outcomes: diagnostic accuracy, clinical outcomes and health systems outcomes (see Appendix E3).

The outcomes selected for each question and the scores assessing their importance are included in the evidence-to-decision tables presented in Appendix E4.

Evidence identification and retrieval, quality assessment and synthesis of evidence

A systematic review team performed a rapid review (initial search on 15 April 2020, with subsequent literature surveillance through 29 April 2020, and update on 28 May 2020). Refer to the full guideline publication for more information on the systematic review [15]. The systematic review team produced a GRADE evidence profile for each PICO question [16]. According to the GRADE methodology, the certainty of evidence is categorized into “high”, “moderate”, “low” and “very low”, based on study limitations, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and other factors [17,18].

The core group conducted an online cross-sectional survey of stakeholders asking them to rate (i) the importance of the outcomes and (ii) their views on the acceptability, feasibility, impact on equity and resource use of the relevant chest imaging modalities (chest radiography, CT and lung ultrasound) in the different clinical scenarios.

Formulation of the recommendations

The GDG formulated the recommendations using the GRADE framework, with explicit consideration of specific factors that may affect the direction and strength of each recommendation (benefits and harms, the certainty of the evidence, values and preferences, resource use, equity, acceptability and feasibility) [11,19]. The direction (whether “in favour of” or “against” an intervention) and strength (whether “conditional” or “strong”) of the recommendations reflects the GDG’s degree of confidence as to whether the desirable effects of the intervention being considered outweigh the undesirable effects.

The methodologist (EAA) developed an evidence-to-decision table for each PICO question (using the GRADEpro software), [17] and used them to guide online discussions [18]. The GDG voted on each of the evidence-to-decision factors, then on the direction and strength of the recommendation using an online voting tool (menti.com). The voting results served as the starting point for building consensus. None of the GDG members expressed opposition to the final strength or direction of any of the recommendations. The recommendation was termed as “based on expert opinion” when the systematic review identified no relevant evidence.

Peer review and quality assurance

The members of the External Review Group provided peer review on the draft report of the guidance. The core group considered and addressed all comments with detailed documentation of the responses. The WHO COVID-19 Publications Review Committee provided oversight and approved the final version of the report.

Results

The literature review identified 28 studies that met the eligibility criteria. Out of the seven PICO questions, four had no identified evidence (PICO 1, 3, 6, 7), one had low certainty evidence (PICO 2), and two had very low certainty evidence (PICO 4, 5). The summary of the evidence by PICO question is as follows:

PICO 1: The systematic review identified no eligible study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of imaging in asymptomatic contacts of patients with COVID-19.

PICO 2: The systematic review identified 23 studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of three imaging modalities in symptomatic patients with suspected COVID-19, against a reference standard, chest radiography (n=3), chest CT (n=19) and lung ultrasound (n=1). None of these studies compared two imaging modalities against each other. The systematic review team judged those studies to be at either high risk of bias (n=17) or moderate risk of bias (n=6). The studies provided limited information regarding clinical presentation (e.g. the severity of symptoms at presentation) and few reported specific criteria for a positive imaging test for COVID-19. Eleven studies did not describe a reference standard to diagnose COVID-19 that included serial RT-PCR or clinical follow-up. The median sensitivity and specificity reported by the included studies were 0.64 and 0.82 for chest radiography; 0.92 and 0.56 for chest CT; and 0.95 and 0.83 for lung ultrasound. The systematic review team judged the certainty of this evidence to be low for chest radiography, chest CT and lung ultrasound. The corresponding evidence-to-decision table available in Appendix E4 provides the counts for true positives, true negatives, false positives and false negatives for four hypothetical prevalence values of COVID-19 infection which were assumed to be 20%, 40%, 60% and 80% among symptomatic patients with suspected COVID-19. The update of the review conducted before the publication of the guide identified five new studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of chest radiography, chest CT and lung ultrasound in symptomatic patients with suspected COVID-19. The synthesized evidence as well as its associated certainty were judged to remain unchanged.

PICO 3: The systematic review identified no eligible study that evaluated any chest imaging modality in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 not yet hospitalized to support decisions on hospital admission versus home discharge on health outcomes.

PICO 4: The systematic review identified no eligible study that evaluated any chest imaging modality in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 not yet hospitalized to support decisions on regular admission versus intensive care unit admission on health outcomes. The update of the review conducted before the publication of the guide identified one new study that evaluated the use of chest imaging in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 not yet hospitalized. The certainty of the evidence was judged as very low.

PICO 5: The systematic review team identified three studies that evaluated chest imaging in patients currently hospitalized with moderate or severe symptoms and suspected or confirmed COVID-19, for predicting mortality or admission at the intensive care unit. The certainty of evidence was judged to be very low.

PICO 7: The systematic review team identified no study that evaluated any chest imaging modality to support the decision on discharge home.

Refer to the full guideline publication for the citations of studies referred in the summary of evidence [15].

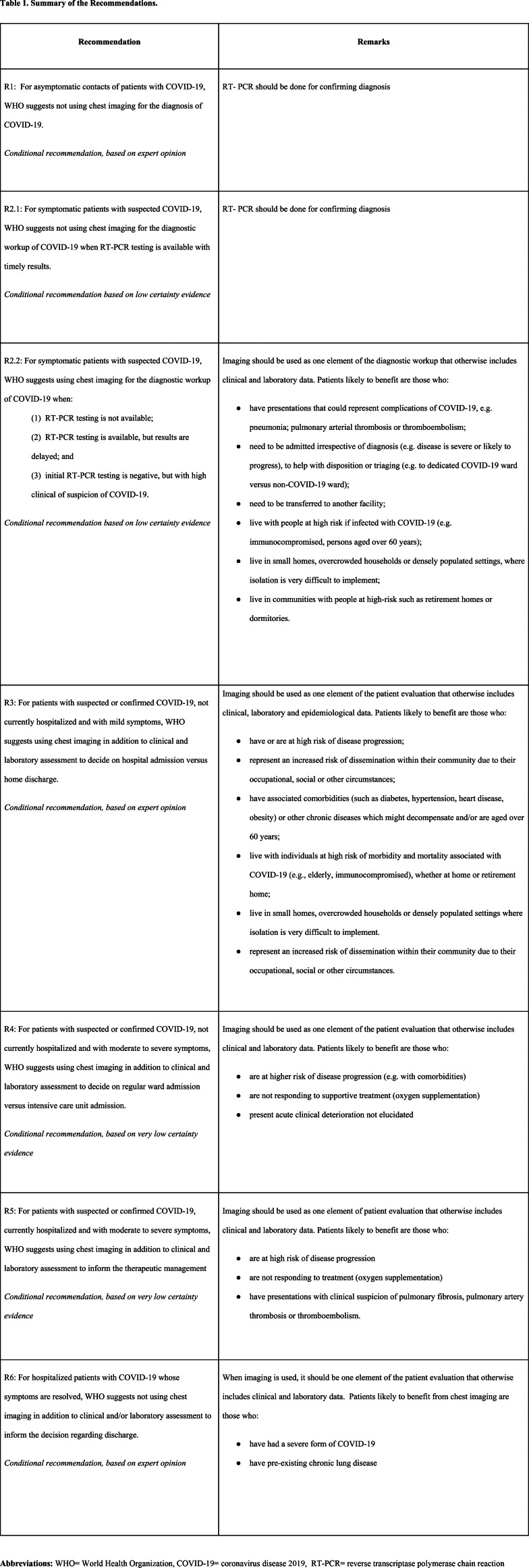

The GDG developed one recommendation for each PICO question with two exceptions: it developed two recommendations for PICO 2 and developed no recommendation for PICO 6 (due to lack of evidence and the rapidly evolving knowledge related to that question). The recommendations for which no evidence meeting inclusion criteria was identified were labelled as based on expert opinion. Table 1 presents a summary of the recommendations. All developed recommendations are conditional, which means that the desirable effects were judged to likely outweigh the undesirable effects under certain conditions. One set of these conditions relates to the characteristics of patients who are likely to benefit from the recommended interventions (listed in Table 1 for each recommendation).

Table 1:

Summary of the Recommendations.

Another set of conditions relates the factors to consider when choosing a specific imaging modality (included in Table 2 for all recommendations). Appendix E5 provides implementation considerations, monitoring and evaluation considerations, and research priorities for the different recommendations. Table 3 lists only those implementation considerations that are common across all recommendations. The evidence-to-decision tables for the different recommendations are included in Appendix E4.

Table 2:

Factors to consider when choosing the specific imaging modality (applies to all recommendations).

Table 3:

Implementation considerations that are common across recommendations.

Discussion

The purpose of the guide is to support WHO Member States in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic by providing up-to-date guidance on use of chest imaging in adult patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, including chest radiography, computed tomography and lung ultrasound. It covers the care pathway from outpatient facility or hospital entry to home discharge. The guidance is provided for patients with different levels of disease severity, from asymptomatic individuals to critically ill patients. Additional guidance on infection prevention and control (IPC) in medical imaging procedures for COVID-19 management is provided in Appendix E6. The IPC guidance addresses both general measures for all imaging procedures and specific precautions for chest radiography, chest CT and lung ultrasound. The guide also promotes quality and safety of radiation use in health facilities, thus enhancing protection and safety of patients and health workers (Appendix E6).

The guide has a number of strengths including its development based on standard methodology [20], the consideration of contextual factors [11], its reporting according the RIGHT statement, and the consideration of stakeholders views [21]. Limitations include that the evidence on which the recommendations are based is either lacking or at best of low certainty, and that scope is relatively narrow (e.g., excluded children, did not address the systemic aspects of the disease). However, the latter was necessary to allow the rapid development of recommendations addressing the most pressing questions.

The recommendations address chest imaging in general, but not specific imaging modalities. While there is accumulating evidence about typical findings with each imaging modality [22], evidence about comparative diagnostic and prognostic value of the different modalities is still lacking. The experience indicates that in most cases chest radiography with portable equipment can provide the information needed at the point of care. In addition to limiting patient transfers it gives the possibility of adapting procedures to reduce staff exposure and increase operational efficiencies (e.g. portable chest radiography obtained through the glass of an isolation room door) [23]. Preliminary studies on lung ultrasound seem promising, in particular for use of portable ultrasound scanners at the point of care, but further evidence still needs to be generated. A CT scan may be the indicated modality for particular patient groups (e.g. those with suspected thrombotic/thromboembolic disease, multi-systemic disease). In health facilities, particularly in LMICs, where CT scans are not available for those patients, policy makers should consider provisions to facilitate patient transfer to reference hospitals where CT scans can be performed. In the long-term, the assessment of clinical, social, economic, organizational and ethical issues should inform decision-making about procurement of imaging technology [24,25]. There is wide variability of the contextual factors across settings (e.g., availability and cost of each modality and availability of the required expertise). Along with other technical considerations, the guide refers to the choice of a chest imaging modality in the remarks that apply to all recommendations (see Table 2). Indeed, the GDG gave due consideration to resource use, impact on equity, acceptability and feasibility when drafting the recommendations.

This guide is primarily intended for health professionals working in emergency departments, imaging departments, clinical departments, intensive care units and other health care settings involved in the diagnosis of COVID-19 and in the management of COVID-19 patients. The document can also be useful for hospital managers and planners, policy-makers, hospital architects, biomedical engineers, medical physicists, logistics staff, water/sanitation and infection prevention and control officers. Health authorities and radiation regulators can use the guide to develop specific national standards relevant to COVID-19 outbreak preparedness, readiness and response in different contexts. Finally, it can be useful to funders that wish to donate equipment and devices as well as funding priority research.

We were able to develop the guideline in about 10 weeks, which fits the 3-month timeframe of ‘rapid’ guidelines [26]. Two main facilitating factors include the existence of a clear and detailed process in place (as described in the WHO handbook for guideline development) [10], and the use of a rapid review process [27]. The latter factor is important considering that conducting the systematic review typically consumes a number of months. In addition, we used a staggered approach when developing the guide: e.g., we started training the GDG members even before the findings of the rapid review were available, and we sent out recommendations for peer review (by the external review group) even before all recommendations were developed. Finally, the most critical factor was probably having a dedicated core group that developed and followed a very strict timeline and worked on keeping a steady momentum. The core group members met almost daily (including weekends) and maintained an intense email communication.

While the guide was developed within a relatively short timeframe, we do not believe this has affected the quality of the recommendations. Indeed, we followed standard WHO process, including proper development of PICO questions, determination and prioritization of outcomes of interest, conflicts of interest declaration and management, reliance on systematically collected evidence, use of GRADE methodology, and use of Evidence to Decision tables. While the rapid review could have missed relevant studies, it is very unlikely that any impactful studies have been missed. We did have all members of the GDG verify eligible studies, and we continually monitored the literature over the period of the project. The online format of the GDG meetings, due to the travel restrictions during the pandemic, did not impede proper discussions. On the contrary, GDG discussions were lively constructive and allowed all members the opportunity to contribute.

Moreover, we conducted a survey of stakeholders to capture their views on factors that were very important to the development of recommendations, namely resource use, impact on equity, acceptability and feasibility. The panel paid attention to the resource implications for low resource settings.

As growing body of literature is confirming the multi-systemic nature of COVID-19 (including the nervous, vascular and cardiac systems, kidneys) [28], this raises questions on whether/when/how imaging other than that of the chest (e.g., cardiac ultrasound, brain MRI, vascular imaging, abdominal imaging) may contribute to early diagnosis and/or management of patients with COVID-19. Specifically, pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 is gaining attention with its relatively high prevalence and the ongoing discussion about its embolic versus intravascular thrombotic mechanism [29,30]. When addressing this question, the GDG members felt that both the published literature and the collective clinical experience were not adequate to justify any recommendation. We are aiming to address it in the next update of the guide.

In the future, guidance and policies for procurement of imaging equipment are needed. There is also a need for research on diagnostic accuracy, and desirable and undesirable impact of the different modalities on clinical and health systems outcomes. Ideally, the clinical studies should consist of well-designed clinical trials that are registered [31], and reported according to standard guidelines [22].

Finally, there is a need for studies addressing contextual factors, including cost, cost effectiveness, impact on equity, acceptability and feasibility of the different imaging modalities. In summary, the guide provides up-to-date guidance on the use of chest imaging in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 for clinicians, and other stakeholders. It also provides research recommendations that can hopefully provide a better evidence base for future updates of the guide.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The Radiation and Health Unit of the World Health Organization (WHO) thank the government of Japan for funding the development of this guide. The funder’s views have not influenced the development and content of this guide. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

We thank the members of the external review group, the systematic review team, and the steering group (see Appendix E1). We also acknowledge Xuan Yu from Lanzhou University (for searching the Chinese language databases and translation); the International Society of Radiology (ISR) (for conducting a survey to inform this guide); Martina Szucsich and Monika Hierath from the European Society of Radiology (ESR) (for technical assistance); Joanne Khabsa from the American University of Beirut (AUB) (for assisting in the virtual panel sessions); Donna Newman and Stewart Whitley from the International Society of Radiographers and Radiological Technologists (ISRRT), Jacques Abramowicz from the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (WFUMB) and the International Society of Radiology (ISR) (for assisting in the development of the guidance on infection prevention and control in imaging practices); April Baller from the Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) pillar (for technical advice); Victoria Willet and Fernanda Lessa and Jocelyne Basseal from the WHO IPC (for reviewing Appendix E6); and Susan Norris from the Guideline Review Secretariat (for technical advice). MDRP affirms that she has listed everyone who contributed significantly to the work.

Funding: Government of Japan

Abbreviations:

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- SARS-CoV-2

- severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- COVID-19

- coronavirus disease 2019

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- GRADE

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- RIGHT

- Reporting Items for practice Guidelines in HealThcare

- GDG

- guideline development group

- LMICs

- low- and middle-income countries

- PICO

- population, intervention, comparison, outcomes

- CT

- computed tomography

- IPC

- infection prevention and control

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus – China: WHO; 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10224):565-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(8):727-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) - Situation Report 22.: WHO; 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200211-sitrep-22-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=fb6d49b1_2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- 8.Blazic I, Brkljacic B, Frija G. The use of imaging in COVID-19 – results of a global survey by the International Society of Radiology. Eur Radiol. Forthcoming; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Use of chest imaging in COVID-19: a rapid advice guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (WHO/2019-nCoV/Clinical/Radiology_imaging/2020.1). Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO.

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development 2014 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/handbook_2nd_ed.pdf?ua=1.

- 11.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;353:i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Yang K, Marušic A, Qaseem A, Meerpohl JJ, Flottorp S, et al. A Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care: The RIGHT Statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;166(2):128-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB, Sverzellati N, Kanne JP, Raoof S, et al. The Role of Chest Imaging in Patient Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multinational Consensus Statement From the Fleischner Society. Chest. 2020;158(1):106-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64(4):395-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapid advice guide: Use of chest imaging in COVID-19: a rapid advice guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (WHO/2019-nCoV/Clinical/Radiology_imaging/2020.1). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64(4):383-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt GH, Thorlund K, Oxman AD, Walter SD, Patrick D, Furukawa TA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 13. Preparing summary of findings tables and evidence profiles-continuous outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2013;66(2):173-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaminski-Hartenthaler A, Meerpohl JJ, Gartlehner G, Kien C, Langer G, Wipplinger J, et al. [GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations]. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2014;108(7):413-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2014;186(3):E123-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petkovic J, Riddle A, Akl EA, Khabsa J, Lytvyn L, Atwere P, et al. Protocol for the development of guidance for stakeholder engagement in health and healthcare guideline development and implementation. Systematic Reviews. 2020;9(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mossa-Basha M, Medverd J, Linnau K, Lynch JB, Wener MH, Kicska G, et al. Policies and Guidelines for COVID-19 Preparedness: Experiences from the University of Washington. Radiology. 2020:201326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health technology assessment of medical devices. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO compendium of innovative health technologies for low-resource settings, 2016-2017. Geneva: World Health Organization.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thayer KA, Schunemann HJ. Using GRADE to respond to health questions with different levels of urgency. Environ Int. 2016;92-93:585-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC medicine. 2015;13:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaim S, Chong JH, Sankaranarayanan V, Harky A. COVID-19 and Multiorgan Response. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45(8):100618-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deshpande C. Thromboembolic Findings in COVID-19 Autopsies: Pulmonary Thrombosis or Embolism? Annals of internal medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lax SF, Skok K, Zechner P, Kessler HH, Kaufmann N, Koelblinger C, et al. Pulmonary Arterial Thrombosis in COVID-19 With Fatal Outcome: Results From a Prospective, Single-Center, Clinicopathologic Case Series. Annals of internal medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasrallah AA, Farran SH, Nasrallah ZA, Chahrour MA, Salhab HA, Fares MY, et al. A large number of COVID-19 interventional clinical trials were registered soon after the pandemic onset: a descriptive analysis. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Atomic Energy Agency . Radiation Protection and Safety in Medical Uses of Ionizing Radiation. IAEA Safety Standards Series No; SSG-46. 2018. [Google Scholar]