Abstract

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is a distinct oculorenal disorder of immune origin and accounts for some cases of unexplained recurrent uveitis. We report three cases of TINU syndrome, one of which had primarily come to us with uveitis. It is the occurrence of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in a patient in the absence of other systemic diseases that can cause either interstitial nephritis or uveitis. TINU syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. Our aim in reporting these cases is to highlight the association of nephritis and uveitis, which together form a distinct clinical disorder called the TINU syndrome.

Keywords: Immunomodulatory agents, steroids, tubulointerstitial nephritis, uveitis

Introduction

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is an oculorenal inflammatory condition, first described by Dobrin et al. in 1975,[1] and is defined by the combination of biochemical abnormalities, tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), and uveitis.[2] More than 200 cases have been reported worldwide in medical literature.[3]

In TINU syndrome, ocular findings may precede, develop concurrently with, or follow the onset of nephritis.[4] A definite diagnosis requires histopathological confirmation.[5]

We report three cases of TINU syndrome, of which the first case had primarily come to us with uveitis. On routine urine examination, she had proteinuria and was subsequently referred to a nephrologist who made a diagnosis of TINU syndrome. The other two were biopsy-proven cases of TINU Syndrome. The second patient was put on topical steroids, but uveitis recurred on every attempt to withdraw steroids; hence, this patient was subsequently put on immunomodulatory agents. The third case had developed complicated cataract due to prolonged usage of steroids.

Case Reports

Case 1

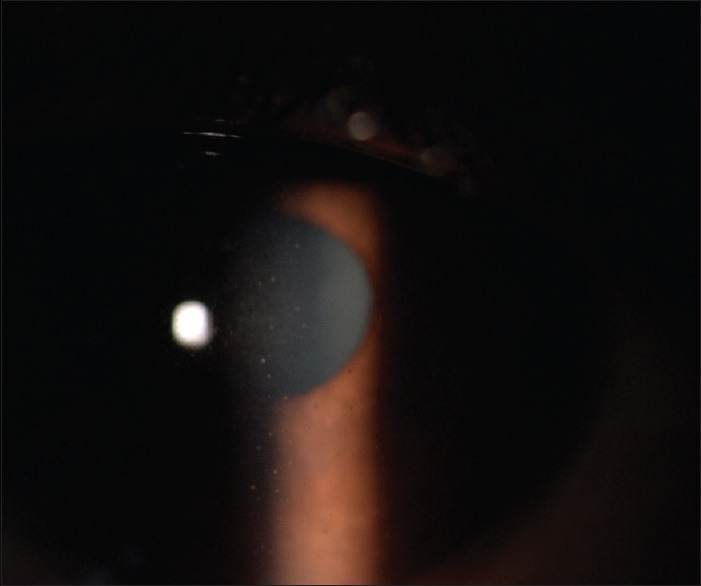

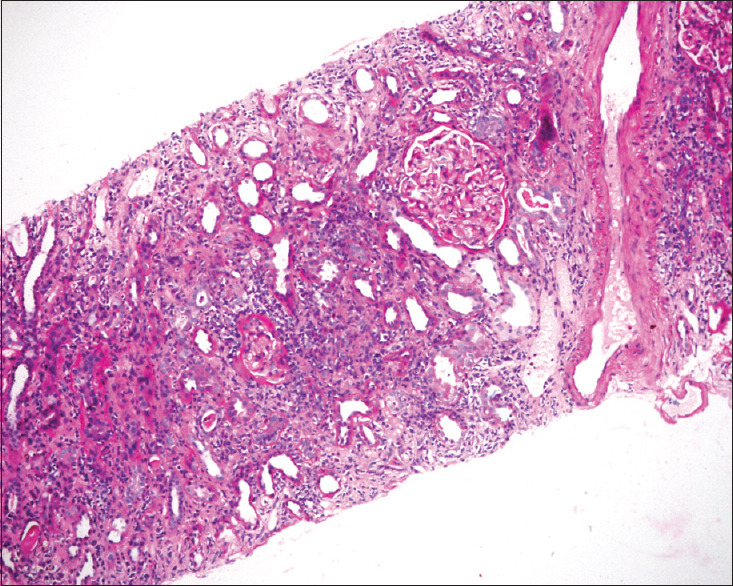

A 19-year-old female patient presented to us with a chief complaint of redness and pain in the right eye (RE) along with low-grade fever and headache for the last few weeks. On examination, her corrected visual acuity at distance was 20/25 in RE and 20/20 in the left eye (LE). Slit-lamp examination revealed circumciliary injection in RE with 2+ flare and 1+ cells. Keratic precipitates (KPs) were nongranulomatous in appearance as shown in Figure 1. Dilated fundus examination was within normal limits. She was started on topical prednisolone eye drops 1% QID and cylcoplegics BD. Systemic examination was unremarkable. On routine laboratory investigation, urine examination revealed low to moderate grade proteinuria. She was subsequently referred to the department of nephrology where percutaneous renal biopsy was performed, which showed features of chronic inflammatory tubulointerstitial nephritis [Figure 2] and a diagnosis of TINU syndrome was made. The patient was put on oral steroids. On follow-up for a period of 9 months, there is no relapse of uveitis in RE.

Figure 1.

Slit-lamp examination revealing nongranulomatous keratic precipitates

Figure 2.

Renal biopsy histopathology showing features of tubulointerstitial lesions with no glomerular or vascular lesions

Case 2

A 20-year-old male patient who had acute interstitial nephritis, diagnosed by renal biopsy, responded well to oral steroid treatment. Three months later, the patient developed painful red eyes. On examination, his visual acuity was 20/40 bilaterally. Slit-lamp examination showed marked circumciliary congestion, 3+ flare, 2+ cells, granulomatous KPs in both eyes. Fundus examination was normal. All other causes of granulomatous uveitis were ruled out. He was put on topical prednisolone acetate 1% eye drops QID and cycloplegics BD. The uveitis persisted for 10 months, and on every attempt to discontinue topical steroids, it again flared up. The patient was subsequently put on methotrexate, 7.5 mg/week, and the steroids were tapered. Regular clinical examination was carried out along with laboratory tests as complete hemograms, liver function test, and kidney function test. The steroids were discontinued and uveitis was controlled on methotrexate. The patient responded well and was relapse free for a period of 7 months on the last examination.

Case 3

A 20yearold female, who was a biopsy proven case of chronic renal failure on dialysis was referred to us for the decreased vision in RE. Her visual acuity was 20/200 RE and 20/25 LE. Slit-lamp examination revealed Grade 1 flare, atrophic iris, and complicated cataract in RE and Grade 1 flare in LE. Fundus was normal. Previous ophthalmic records showed chronic uveitis. She underwent cataract surgery under steroid cover and is relapse free for 12 months.

Discussion

TINU syndrome is an oculorenal inflammatory condition defined by the combination of biochemical abnormalities, TIN, and uveitis.[2]

A review of 133 cases with TINU syndrome reported in the survey of ophthalmology ocular findings preceded (21%), developed concurrently with (15%), or followed (65%) the onset of interstitial nephritis. Uveitis was documented up to 2 months before or up to 14 months after the onset of systemic symptoms.[4] As the diagnosis of TINU syndrome is one of the exclusions, a clinician must be vigilant to diagnose it.

Uveitis mostly involves the anterior segment and may be bilateral. Common ocular symptoms are eye pain and redness, decreased vision, and photophobia. Visual impairment occurs in only few cases, typically in the presence of posterior uveitis.[4]

Anterior segment findings include anterior chamber cells and flare, conjunctival injection, and keratic precipitates. The uveitis is typically nongranulomatous, but granulomatous uveitis has also been reported.[4] Posterior segment findings may include panuveitis, disc edema,[5] and neuroretinitis.[6]

Recurrence of uveitis can occur and may persist for several years in a group of cases. The visual prognosis is mostly good.

In all the three of our cases, uveitis was confined to anterior segment only, two had bilateral involvement, and one was unilateral. Visual complication was in one of our patients who had complicated cataract. Mostly, uveitis is nongranulomatous, rarely it can be granulomatous,[6] as seen in our second case.

Initial laboratory testing in patients with TINU syndrome typically revealed poor renal function, including elevated blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels. If the serum creatinine or urinalysis is found to be anomalous, a urinary beta-2-microglobulin level should be measured.[7]

Renal function typically returned to normal or near-normal values upon recovery. Mandeville et al. have set out the diagnostic criteria for “definite” TINU, which requires the presence of histopathologically confirmed acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and typical uveitis.[4]

The acute interstitial nephritis of TINU syndrome usually resolves spontaneously.[8] The treatment for anterior uveitis of TINU syndrome has been with topical corticosteroids and cycloplegic agents. Uveitis in the setting of TINU syndrome appears to be more persistent and bothersome than the nephritis.

Immunomodulatory chemotherapeutic agents may be used when uveitis is resistant to systemic steroids or to reduce ocular or systemic toxicity from corticosteroids.[9] In one of our cases, we had put the patient on methotrexate as recurrence was reported every time we tried to taper steroids.

Diseases which can present with acute interstitial nephritis along with ocular abnormalities need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of TINU syndrome and include Sjogren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and toxoplasmosis.[10]

The clinician must have a high index of suspicion to diagnose TINU syndrome, as the renal disease and uveitis may occur many months apart. Recent studies do not show any gender predisposition. For patients presenting initially with uveitis, the constitutional symptoms listed prompt the ophthalmologist to investigate renal function with a serum creatinine level and routine urinalysis.

The present understanding shows that subclinical signs of uveitis must be aggressively looked for, especially in those patients who have tubulointerstitial disease of unknown origin.[2]

Urinary beta-2 microglobulin has emerged as a new laboratory screening test, and the role of kidney biopsy in differentiating TINU from sarcoidosis continues to evolve and hold its importance. Genetic studies have identified HLA-DQA1*01, HLA-DQB1*05, and HLA-DRB1*01 as high-risk alleles. The identification of anti-mCRP antibodies suggests a role for humoral immunity in disease pathogenesis.[11]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/ have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dobrin RS, Vernier RL, Fish AL. Acute eosinophilic interstitial nephritis and renal failure with bone marrow-lymph node granulomas and anterior uveitis. xsA new syndrome. Am J Med. 1975;59:325–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han JM, Lee YJ, Woo SJ. A case of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in an elderly patient. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:398–401. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2012.26.5.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parameswaran S, Mittal N, Joshi K, Rathi M, Kohli HS, Jha V, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Nephrol. 2010;20:103–5. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.65307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandeville JT, Levinson RD, Holland GN. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46:195–208. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menezo V, Ram R. Tubulo-interstitial nephritis and uveitis with bilateral optic disc oedema. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:536–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khochtali S, Harzallah O, Hadhri R, Hamdi C, Zaouali S, Khairallah M. Neuroretinitis: A rare feature of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:629–33. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepple KL, Lam DL, Finn LS, Gelder VR. Urinary ß2-microglobulin testing in pediatric uveitis: A case report of a 9-year-old boy with renal and ocular sarcoidosis. Ophthalmol. 2015;20:101–5. doi: 10.1159/000381092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortajil F, Rezki H, Hachim K, Zahiri K, Ramdani B, Zaid D, et al. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and anterior uveitis (TINU syndrome): A report of two cases. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2006;17:386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gion N, Stavrou P, Foster CS. Immunomodulatory therapy for chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis-associated uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:764–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto K, Fukunari K, Ikeda Y, Miyazono M, Kishi T, Matsumoto R, et al. A report of an adult case of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome, with a review of 102 Japanese cases. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:119–23. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.892788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakzad-Vaezi K, Pepple KL. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28:629–35. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]