Abstract

Introduction

The importance of menstrual health has been historically neglected, mostly due to taboos and misconceptions around menstruation and androcentrism within health knowledge and health systems around the world. There has also been a lack of attention on ‘period poverty’, which refers to the financial, social, cultural and political barriers to access menstrual products and education. The main aim of this research is to explore menstrual health and experiences of period poverty among young people who menstruate (YPM).

Methods and analysis

This is a convergent mixed-methods study, which will combine a quantitative transversal study to identify the prevalence of period poverty among YPM (11–16 years old), and a qualitative study that will focus on exploring menstruation-related experiences of YPM and other groups (young people who do not menstruate (YNM); primary healthcare professionals; educators and policy-makers). The study will be conducted in the Barcelona metropolitan area between 2020 and 2021. Eighteen schools and 871 YPM will be recruited for the quantitative study. Sixty-five YPM will participate in the qualitative study. Forty-five YNM and 12 professionals will also be recruited to take part in the qualitative study. Socioeconomic and cultural diversity will be main vectors for recruitment, to ensure the findings are representative to the social and cultural context. Descriptive statistics will be performed for each variable to identify asymmetric distributions and differences among groups will be evaluated. Thematic analysis will be used for qualitative data analyses

Ethics and dissemination

Several ethical issues have been considered, especially as this study includes the participation of underage participants. The study has received ethical approval by the IDIAPJGol Research Ethics Committee (19/178 P). Research findings will be disseminated to key audiences, such as YPM, YNM, parents/legal tutors, health professionals, educators, youth (and other relevant) organisations, general community members, stakeholders and policy-makers, and academia.

Keywords: menstrual health, health services, education, young people, social medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will address an important research gap on menstrual health and period poverty in high-income settings, from a gender and intercultural approach.

A mixed-methods design will allow for the integration of quantitative (descriptive) and qualitative (in-depth) data.

This study includes collaborations with a variety of key actors, following Responsible and Research Innovation (RRI) guidelines.

The dissemination strategy includes a variety of audiences and will be cocreated with study participants.

The combination of data collection methods, and using an RRI and participatory research approach will require increased resources and time.

Introduction

Research on menstrual health is still scarce. Moreover, most research has been conducted in low-income countries,1–3 neglecting its need in high-income regions. Menstrual health is associated with the access of people who menstruate to accurate information on menstruation, menstrual products and clean and safe washing facilities. Menstrual health also needs to be understood as a tool for health promotion, and it is linked to experiences related to the menstrual cycle. Good menstrual health also includes tackling menstruation-related taboos, stigma and discrimination.4 Promoting menstrual health is key to reach gender equity and promote health among people who menstruate. Menstrual health has even been suggested as a vital sign.5 6 Despite the growing international commitment to focus on promoting menstrual health, there is still much to be done.2 In this study, we will focus on ‘people who menstruate’ rather than ‘women’ not to exclude people who have a menstrual cycle but are not women/do not identify as women (eg, male transsexual or male transgender).

Activist-led movements have increased awareness on the negative impact on the cost of menstrual products, sociocultural practices and views on menstruation have on women’s health and well-being. These movements aim at promoting a ‘menstrual culture’ that demystifies the menstrual cycle and are based on feminist and sociocultural paradigms. Together with some health professionals, activism in Spain is already suggesting body awareness and knowledge about one’s menstrual cycle as tools for health promotion. Menstrual health education is crucial to understand and improve how people who menstruate relate to their menstrual cycle.4 7 However, the role of the ‘menstrual products’ and pharmaceutical industries in women’s menstrual health is strong. These are the companies which are delivering menstrual health education in schools in Spain. Considering that these events are enough for ‘menstrual health education’ is questionable, as these companies rather focus on selling their products and on medicalising menstruation instead of delivering high-quality education on the menstrual cycle and the wide range of products available.8 In the meantime, many people who menstruate in Spain seem to still be unaware of how their menstrual cycle works and its relationship with their overall health.8

Focusing on young people is crucial to understand their conceptions and experiences of menarche (first menstruation). Good health education among young people is a priority as their bodies are changing while reaching adulthood. As previously reported in a study by Plan International UK,4 it is essential that young people get access to menstrual health education, health services and products that protect their health and well-being. In this study, menstrual-related myths and taboos were prevalent among young people. Stigma and embarrassment were a reality for many girls as, for example, most of them did not feel comfortable discussing menstruation with their school teachers. Besides and very importantly, most girls explained how they were unaware of what was happening in their bodies and what to do when they first got their menstruation.4 Another reason to focus on children and adolescents is that they are vulnerable groups to experience stigma, discrimination, and social and health inequities.

Inequities between people who menstruate and people who do not menstruate are also to be highlighted. These are, for example, visible through the (still prevailing) stigma and discrimination towards people who menstruate and menstruation itself.4 In line with this argument, productivity loss due to presentism and absenteeism at schools and workplaces among people who experience menstrual pain needs to be considered too.9 Social and health inequities among people who menstruate (compared with people who do not menstruate) can be also explained when menstruating is a source of social (eg, normalisation of menstrual pain) and structural (eg, not being able to get sick leave for menstrual pain) sanctions.

The menstrual cycle is not a health condition to be medicalised. However, this is not how it seems to be conceived within society and healthcare systems. This project stems from an opposition to the predominant androcentrism in health science and healthcare systems. The concept of androcentrism refers to having men (male humans) as the reference, the norm and the example for all humans. In the health context this has translated into the invisibilisation of women, the female body and women’s health in health science, policy and practice.8 10–12 As briefly mentioned already, this project also questions the role of the industry (menstrual products and pharmaceutical) in the medicalisation and sociocultural conceptualisations of the menstrual cycle and menstruation.8 Instead, it is important that the menstrual cycle is understood as a natural process that is associated with good health. This means that educating society and professionals is a priority to promote health among young people who menstruate (YPM). Increased education and a more positive conceptualisation of the menstrual cycle and menstruation could help YPM being more aware of their bodies. In turn, this could help encourage menstruators to care for their menstrual and general health, and aid the identification of some health conditions such as endometriosis.13 Improved education could also lead the disassociation of menstruation and pain, and challenge myths and beliefs around the menstrual cycle and the use of hormonal contraception. Last but not least, education could reduce menstruation-related stigma and discrimination.

One aspect of menstrual health is the access to menstrual products. Research in other countries, such as Uganda3 and the UK4 has highlighted experiences of period poverty among young women. This term refers to barriers (financial, social, cultural and political) in accessing menstrual products, menstrual education and access to healthcare services. Plan International UK4 recently explored period poverty in a high-income country through focus groups with 64 adolescents. Their report revealed that 1 in 10 adolescents experience period poverty in the UK. However, and to our knowledge, there have been no attempts to identify the prevalence of period poverty at a community or population level.

Despite social movements to promote menstrual health and to reduce menstrual products’ taxes in the last few years, menstrual health in Spain continues to be ignored. This is reflected in national and regional public health strategies, in which menstrual health is never present. Even when 27.7% of children were at risk of poverty in Catalunya in 2017,14 experiences of period poverty among children and adolescents have not been explored. Social, cultural, financial and political barriers to promote menstrual health, stigma and discrimination and the elimination of period poverty have also been overlooked. Besides, menstrual products are not considered necessity goods by law in Spain, holding a 10% tax (Spanish Law 37/1992, 28 December 2018). Although in October 2018 the Spanish government guaranteed that tax retentions on menstrual products should be reduced to 4%, this tax reduction has not been applied yet.

This study will explore menstrual health and experiences of period poverty among YPM. We also hope to identify barriers and facilitators that could promote menstrual health through the access of good-quality education and healthcare. Also, to explore ways to improve menstrual health experiences in YPM and reduce period poverty. This study will provide recommendations for future research, policy and practice, aiming at addressing social inequities of health in YPM (and especially among those that may be experiencing period poverty) in Spain and other high-income countries with similar sociocultural contexts. The views of young people who do not menstruate (YNM) and professionals will also be considered in this project. Through this research, our team aims to start a line of research on menstrual health and period poverty in the area of Barcelona, hoping to scale up the study to other areas in Spain.

Aims and objectives

This project aims to explore menstrual health and experiences of period poverty among YPM (11–16 years old). The study will be conducted in the Barcelona metropolitan area between 2019 and 2021.

The objectives will be:

To identify the prevalence of period poverty in YPM.

To explore sociocultural understandings of menstruation and menstrual health in YPM, YNM of the same age, health professionals, teachers, activists and policy-makers.

To explore experiences of menstruation and period poverty among YPM.

To explore menstruation-related stigma and discrimination.

To identify barriers and facilitators to promote menstrual health, and to access education and healthcare for menstrual health.

To identify opportunities to improve menstrual health-related experiences of YPM and reduce period poverty.

Provide recommendations for future research, policy and practice.

Methods and analysis

The study will be coordinated by the research team at the (Research Centre name). However, a working group of women that includes health professionals, educators, youth representatives and menstrual health activists has been composed, considering responsible research and innovation (RRI) guidelines.15 The members of the working group will regularly contribute to the development of the project attending regular meetings. They will also be involved in developing key study materials (eg, study protocol, non-validated questionnaire, topic guides) and writing research publications and other dissemination materials. Taking this RRI approach will be key to conduct inclusive research not only for but with the community and other key agents. This research is based on a gender-based8 16 17 and intercultural approach.18–20 These approaches go in line with acknowledging sociocultural differences and embracing a respectful and non-discriminatory perspective on research.

Study design

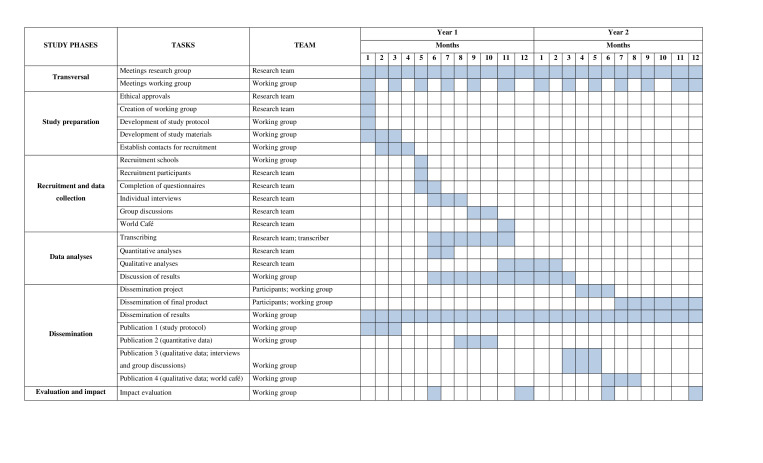

This research is a convergent mixed-methods study that will include a quantitative study and a qualitative study. Quantitative research will allow to quantify the extent of period poverty and some menstrual health experiences. Qualitative research will provide an in-depth exploration of these phenomena. It will start in September 2019 and end in September 2021. A Gantt chart is provided in figure 1. Data will be collected in Catalan and Spanish, the two official languages in the Barcelona metropolitan area.

Figure 1.

Gantt chart.

Quantitative study

This is a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study. A non-standardised questionnaire (see online supplementary material) will be used to calculate the composite main variable ‘period poverty’. Other variables that will be measured and will be used to develop the variable ‘period poverty’. These will be: (1) use of menstrual products, (2) financial (and other) barriers to access menstrual products, (3) use of hormonal contraception, (4) period pain and menstrual disorders, (5) mental health, (6) access to menstrual health consultations, (7) menstruation-related school absenteeism, (8) menstruation-related interference on school performance and other activities, (9) menstruation-related stigma and discrimination, (10) access to menstrual health education and (11) menstrual hygiene and management.

bmjopen-2019-035914supp001.pdf (158.5KB, pdf)

Sociodemographic data will also be collected (age, school, primary healthcare centre, deprivation index, household composition). All variables and sociodemographic data (except for the deprivation index) will be collected using the self-reported questionnaire. The deprivation index will be calculated based on available databases such as the MEDEA (Mortalidad en áreas pequeñas Españolas y Desigualdades Socioeconómicas y Ambientales) deprivation index.21

Qualitative study

There will be three phases of data collection for the qualitative study:

Phase I. Semistructured interviews using photo elicitation techniques22: 20 YPM will take part in semistructured interviews using photo elicitation techniques. These interviews will take place in schools making sure that participants are in a familiar and comfortable environment. The interviews will focus on objectives 2–4.

Phase II. Group discussions: Nine group discussions (three with YPM only, three with YNM and three mixed) will be run with an estimate of 45 YPM and 45 YNM. Participants for the group discussions will be stratified by age (11–12 years old, 13–14 years old and 15–16 years old). Group discussions will be conducted within the natural context of a classroom. Observation and group discussion techniques will be used to collect data. Objectives 2–6 will be covered in this phase of data collection.

Phase III. World Café23 Health professionals, teachers, policy-makers, activists and youth representatives will be invited to participate in a world café. There will be a maximum of 12 professionals in the session. The aim of phase III will be to mainly address objectives 4–6.

Materials

Quantitative study

A non-standarised questionnaire has been devised for this study by the working group (see online supplementary file S1). Several meetings were organised to work on the development of the variables and the questionnaire, following the guidance of previous research and published work on questionnaire design.24

Qualitative study

Topic guides will be developed for each phase of the qualitative study. Developing the topic guides will be a collaborative process between the research team and the working group. The topic guides will be based on the aims of this research, previous evidence, the team’s expertise and data previously collected for this study (phase II and phase III).

The main topic areas will be (1) sociocultural understandings of menstruation and menstrual health; (2) personal experiences of menstruation; (3) experiences of period poverty; (4) experiences of menstruation-related stigma and discrimination; (5) barriers and facilitators to promote menstrual health, and to access education and healthcare for menstrual health; and (6) opportunities to improve menstrual health-related experiences of YPM and reduce period poverty.

All materials for the quantitative and qualitative studies will be piloted with the target population before using them for data collection.

Participants

There will be different groups of participants: YPM, YNM and professionals (health professionals, teachers, policy-makers, activists and youth representatives).

Participant selection

For both the quantitative and qualitative studies recruitment will be non-probabilistic (as not all schools and individuals will have the same probability of being recruited) and purposive (as schools and participants will be selected based on the requirements of the study).

YPM and YNM will be recruited from (public, private and semiprivate) schools in the Barcelona metropolitan area. Schools will be identified to be representative of the socioeconomic diversity in the Barcelona metropolitan area. The MEDEA index21 will be used to determine the socioeconomic level of each school. Cultural diversity will also be a factor for recruiting schools and individuals. The team will ensure that the experiences of socially excluded communities, such as the gipsy community and migrants, are represented in this research. Considering that around 18 schools will be recruited, we will aim to recruit three or four schools from each of the five MEDEA levels. First, permission will be requested from the council of each municipality where recruitment will take place. Then, schools will be contacted and informed about the study, based on a list of schools in the Barcelona metropolitan area and professional contacts of the working group. The research team will organise meetings at participating schools to inform staff and adolescents about the study. Information sheets and consent forms will be given to adolescents to inform and ask parents and legal tutors for consent to participate. An adapted information sheet will be given to minors. Parents and legal tutors will be asked to return a signed copy of the consent form if they want their children to participate. This procedure will be used for each stage of the project involving adolescents (quantitative study and phase I and II of the qualitative study).

In phase III of the qualitative study, professionals will be recruited using snowballing techniques and by identifying key informants for this study. Diversity in the professionals’ background and expertise will be considered to ensure diversity in the discourses. Participants will be required to sign an informed consent to take part in the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in tables 1–3. The researchers will not actively exclude people with functional diversities, unless they do not meet the inclusion criteria (eg, they cannot give consent or communicate with the researchers).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of young people who menstruate (YPM)

| YPM | |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Are between 11 and 16 years old | Are below 11 or above 16 years old |

| Are attending a participating school | Have not (and will not) menstruate |

| Have (or will) menstruate | Cannot understand and/or provide consent |

| Have given their consent to participate | Cannot communicate well in Catalan or Spanish |

| Parents or legal tutors have signed the consent form | |

| Have a good command of Catalan or Spanish | |

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of young people who do not menstruate (YNM)

| YNM | |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Are between 11 and 16 years old | Are below 11 or above 16 years old |

| Are attending a participating school | Have (or will) menstruate |

| Have not (and will not) menstruate | Cannot understand and/or provide consent |

| Have given their consent to participate | Cannot communicate well in Catalan or Spanish |

| Parents or legal tutors have signed the consent form | |

| Have a good command of Catalan or Spanish | |

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of professionals

| Professionals | |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Have experience working in relevant areas of/for menstrual health | Do not have experience working in relevant areas of/for menstrual health |

| Have signed the consent form | Cannot understand and/or provide consent |

| Have a good command of Catalan or Spanish | Cannot communicate well in Catalan or Spanish |

Sample size

Quantitative study

A total of 871 YPM will be recruited for the quantitative study in 18 schools in the Barcelona Metropolitan area. The sample size is based on power calculations considering the composite variable ‘period poverty’ as the main variable. Maximum indetermination of the main variable (proportion of 50%) was assumed. It was also considered that there are 53 354 young girls attending schools in the Barcelona metropolitan area between 11 and 16 years old. These assumptions were considered in order to obtain a precision of 5%, expecting that 50 young girls of each participating school will take part in the study. Also, due to the effect of the design an interclass correlation of 0.0263 will require a minimum of 871 participants (and 18 schools). These estimates have been calculated assuming an alfa risk of 5%. PASS software was used for the sample size calculations (PASS V.15).

Qualitative study

Sixty-five YPM, 45 YNM and 12 professionals (health professionals, teachers, policy-makers, activists and youth representatives) will be recruited for the qualitative study. The sample size will be dependent on data saturation.

Data analysis plan

Quantitative study

Descriptive statistics will be used for each variable to identify asymmetric distributions. The continuous variables will be analysed as mean (SD) or median (25th and 75th centiles) based on the normality/non-normality of the distribution, and categorical variables will be described as percentages. To evaluate differences among groups, the appropriate statistics will be applied based on the type of variable and their distribution (χ2, F-distribution, Student’s t-distribution, analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis). To estimate the magnitude of the associations between the selected variables and period poverty, prevalence ratios and their 95% CIs will be computed by general linear models (Poisson regression models with robust variance and logistics models).

Qualitative study

Qualitative data will be analysed using thematic content analysis.23 Once the audio recordings are transcribed, the researchers will familiarise themselves with the data. This will lead to preanalytical insights of the data. The next step will be to (1) identify relevant themes within the text, (2) divide the text into units of meaning, (3) coding of the data, (4) generation of categories by grouping codes, (5) analysis of each category and (6) elaboration of new text. Results will then be discussed with the working group until consensus is reached (triangulation).

Patient and public involvement

The research questions and aims of this study were driven by community-led social movements on menstrual health and period poverty. Key agents and community members were consulted to design the study, being some of these agents part of the working group. The working group will be actively involved in all stages of the study. Together with participants, the working group will also contribute to the communication and dissemination of the findings (see Dissemination Strategy section on page 12). All materials used for this study (eg, questionnaire and topic guides) will be designed and piloted with the target population.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

We have obtained the necessary ethical approvals prior to the start of the research from our organisation (IDIAPJGoL) (19/178 P). We have considered a number of ethical issues. A main consideration is that this research involves the participation of individuals who are not able to give consent (minors). Adolescents’ consent will be granted through representation (ie, parents or legal tutors) according to the Spanish Law on Biomedical Research (14/2007).

All activities included in the study will be carried out according to existing guidance in ethics as indicated in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights adopted by UNESCO (19/10/2005); the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine (1997) and its additional protocol on biomedical research (2005); the Helsinki Declaration (2013) and relevant EU laws (European Parliament and Council Directive 2001/20/EC); the Spanish Law on Biomedical Research (14/2007); and the LOPD (Spanish Law on Personal Data Protection) (3/2018).

Informed consent

Verbal and written informed consent will be requested from all participants prior to their participation in the study. Most participants will be minors. This has important ethical implications. All information will be given to underage participants in a comprehensive way, and study materials will be adapted to ensure readability and comprehensiveness. Parents or legal guardians will be notified of their adolescents’ invitation to the study. A signed written consent will be requested from all parents or legal guardians for all underage participants. The researchers will ensure that participants are able to consent, and that they understand what their participation entails.

Confidentiality and anonymity

Confidentiality and anonymity will be carefully ensured. Contact details will only be requested to those participants that are willing to take part in succeeding stages of the study. Physical identifiable data will be securely stored at the IDIAPJGoL in a locked cabinet. Digital information will be securely stored at the IDIAPJGoL secure portal. Only the research team will have access to the data. All data presented when disseminating the findings from this study will be anonymised. All identifiable data will be removed from transcriptions and participants will be assigned a participant code. Anonymity in the photographs used in the photo-elicitation interviews will also be ensured. The team will do this by not using photographs in which people are identifiable, unless written consent is given from identifiable people in the photographs. Anonymised data will be made available on request to the authors.

Potential risks

Taking part in this study will involve the discussion of sensitive topics (ie, menstrual health, situations of inequity, sexual relationships and other related topics) and involves the inclusion of a vulnerable group (minors). Discussing sensitive topics and the inclusion of minors are necessary for the purposes of this study. In order to minimise these issues, information about the nature of the study will be disclosed prior to seeking consent and before data collection. The researchers will conduct the study sensitively at all times.

A protocol has been prepared in case the researchers had immediate concerns of harm, or a participant gets distressed during their participation in the study. If this happened with underage participants, their school tutor and parents will be informed (with the participants’ permission). Participation will be paused or stopped if a participant gets distressed. It will be the participant’s decision whether they decide to continue taking part in the study. The research team will ensure that all participants are able to seek support and/or advice if needed.

All participants will be made aware of their right to withhold information that they are not willing to share, as well as withdrawing from the study or removing their data at any time (prior to data analyses).

Participants taking part in the interviews, group discussions and World Café will receive a €10 voucher as a token of thanks for their participation. Participants will also receive a debriefing form that includes a list of resources (books, websites and Instagram accounts) to learn about menstrual health.

Dissemination strategy

Findings will be disseminated to key audiences. These will be YPM, YNM, parents and legal tutors, health professionals, educators, youth (and other relevant) organisations, general community members, stakeholders and policy-makers, and academia. Back translation methods will be used to ensure the quality of any translations to English.

The dissemination strategy will include a dissemination project produced by YPM and YNM, with the support of the research team. The content and format will be chosen by YPM and YNM involved in the development of this dissemination project. Examples of formats would be an art exhibition or a book.

The working group will also organise meetings and workshops at ‘citizen science’ events and schools, aimed at several key audiences. These meetings and workshops will involve study participants (YPM, YNM and professionals) who will colead the sessions.

The working group will prepare short reports, policy briefs, presentations and meetings with stakeholders and policy-makers, activists, health professionals, educators and youth (and other relevant) organisations. The materials, presentations and meetings will be prepared in collaboration with study participants.

On the other hand, scientific publications will be prepared. The study will also be presented at national and international conferences. This part of the strategy will be led by the research team, with the collaboration of the working group and study participants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all women (and men) from the community who contributed to the ideas captured in this protocol. We would like to specially thank Carmen Revuelta Lisa, Ramona Ortiz López and Mònica Isido Albaladejo for their contributions to elaborating the materials and setting up recruitment and data collection. Also, we want to acknowledge Patryk Bialoskorski for his contributions revising the language in this article.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Lauramedp, @ABerenguera

Contributors: LM-P has led and coordinated the conception and design of this study. She has written this manuscript. AB has been involved in the conception and design in this study. She has reviewed and made substantial contributions to this manuscript. TL-J has contributed to the design of the quantitative study, performed power calculations and written the plan for the quantitative data analyses. He has reviewed and made substantial contributions to this manuscript. CJ-A, CV-L, RT-V, DP, LH, PBC, ESL and JMF have contributed to the design of this study. She has reviewed and made substantial contributions to this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health, project number P-2019-A-01.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Haque SE, Rahman M, Itsuko K, et al. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: an intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004607–9. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommer M, Schmitt M, Gruer C, et al. Neglect of menarche and menstruation in the USA. Lancet 2019;393:2302. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30300-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery P, Hennegan J, Dolan C, et al. Menstruation and the cycle of poverty: a cluster Quasi-Randomised control trial of sanitary pad and puberty education provision in Uganda. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166122. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tingle C, Vora S. Break the Barriers : Girls ’ Experiences of menstruation in the UK. Plan Int UK 2018:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matteson KA, Zaluski KM. Menstrual health as a part of preventive health care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2019;46:441–53. 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care ACOG Committee opinion no. 651: menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e143–6. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botello Hermosa A, Casado Mejía R. Significado cultural de la Menstruación en Mujeres Españolas. Cienc Enferm 2017;23:89–97. 10.4067/S0717-95532017000300089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valls-Llobet C. Mujeres, salud Y poder. Madrid: Cátedra (Feminismos), 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoep ME, Adang EMM, Maas JWM, et al. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32 748 women. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026186:10. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levinson R. Sexism in medicine. Am J Nurs 1976;76:426–31. 10.2307/3423886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiebinger L. Skeletons in the closet: the first illustrations of the female skeleton in eighteenth-century anatomy. Representations 1986:42–82. 10.2307/292843511618033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin E. The egg and the sperm: how science has constructed a romance based on Stereotypical male-female roles. Signs 1991;16:485–501. 10.1086/494680 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Women's experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2015;41:225–34. 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IDESCAT Encuesta de condiciones de vida 2017, 2018. Available: https://www.idescat.cat/novetats/?id=2991&lang=es

- 15.Owen R, Macnaghten P, Stilgoe J. Responsible research and innovation: from science in society to science for Society, with Society. Science and Public Policy 2012;39:751–60. 10.1093/scipol/scs093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ussher JM. The madness of women. New York: Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler J. Gender trouble. New York: Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kastoryano R. Multiculturalism and interculturalism: redefining nationhood and solidarity. Comp Migr Stud 2018;6:17. 10.1186/s40878-018-0082-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleckman JM, Dal Corso M, Ramirez S, et al. Intercultural competency in public health: a call for action to incorporate training into public health education. Front Public Health 2015;3:210. 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapata-Barrero R. Interculturalism in the post-multicultural debate: a defence. Comp Migr Stud 2017;5:14. 10.1186/s40878-017-0057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felícitas Domínguez-Berjón M, Borrell C, Cano-Serral G, et al. Construcción de un índice de privación a partir de datos censales en grandes ciudades españolas (Proyecto Medea). Gac Sanit 2008;22:179–87. 10.1157/13123961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research for health: process to outcomes. 2nd ed San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berenguera A, Fernández de Sanmamed MJ, Pons M, et al. To listen, to observe and to understand. Bringing back narrative into the health sciences. Contributions of qualitative research. Barcelona: Institut Universitari d’Investigació en Atenció Prim ria Jordi Gol (IDIAPJGol), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boynton PM, Greenhalgh T. Hands-on guide to questionnaire research: selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. Br Med J 2004;328:1312–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035914supp001.pdf (158.5KB, pdf)