Abstract

Major stratospheric sudden warmings (SSWs) are the largest instance of wintertime variability in the Arctic stratosphere. Due to their relevance for the troposphere-stratosphere system, several previous studies have focused on their potential response to anthropogenic forcings. However, a wide range of results have been reported, from a future increase in the frequency of SSWs to a decrease. Several factors might explain these contradictory results, notably the use of different metrics for the identification of SSWs, and the impact of large climatological biases in single-model studies. Here we revisit the question of future SSWs changes, using an identical set of metrics applied consistently across 12 different models participating in the Chemistry Climate Model Initiative. From analyzing future integrations we find no statistically significant change in the frequency of SSWs over the 21st century, irrespective of the metric used for the identification of SSWs. Changes in other SSWs characteristics, such as their duration and the tropospheric forcing, are also assessed: again, we find no evidence of future changes over the 21st century.

1. Introduction

Stratospheric sudden warmings (SSWs) are the largest events of the wintertime polar stratospheric variability in the Northern Hemisphere, consisting of a very rapid temperature increase leading to a reversal of the westerly wintertime circulation (the polar vortex). In observations, SSWs occur roughly with a frequency of 6 SSWs per decade (e.g., Charlton and Polvani, 2007). However, large variability on intra- and inter-decadal time scales has been reported (Labitzke and Naujokat, 2000; Schimanke et al., 2011).

SSWs also play an important role in the dynamical coupling between the stratosphere and troposphere. Their main precursors are known to originate in the troposphere, as SSWs are triggered by an anomalously high injection of tropospheric waves that propagate into the stratosphere where they deposit momentum and energy, decelerating the mean flow (Matsuno, 1971; Polvani and Waugh, 2004). More importantly, their effects are not restricted to the stratosphere: SSWs also impact the tropospheric circulation and surface climate for up to two months (e.g., Baldwin and Dunkerton, 2001). Given their importance for seasonal forecasting, SSWs have been studied with great interest, as they are likely to provide a source of improved weather forecasts at intraseasonal scales (Sigmond et al., 2013).

One question of particular relevance is whether SSWs will change in the future climate, as a consequence of increasing greenhouse gases (GHG) concentrations and ozone recovery. The answer to this question has proven elusive since the first studies nearly 20 years ago. While Mahfouf et al. (1994) found an increase in the frequency of SSWs under doubled CO2 conditions, Rind et al. (1998) reported a decrease, and Butchart et al. (2000) did not find any change that might be attributed to increasing GHG concentrations. And, in spite of an improved stratospheric representation and more realistic model features in the last decade, a clear consensus as to future SSW changes is still missing (Charlton-Perez et al., 2008; Bell et al., 2010; SPARC CCMVal, 2010; Mitchell et al. 2012a and b; Hansen et al., 2014).

Several potential reasons that might explain the uncertainty in the projections of SSW changes have been proposed in the literature. One is the combination of different aspects of future climate change with opposing effects on the Arctic stratosphere, such as the projected ozone recovery, increasing GHG concentrations and their induced changes in global sea surface temperatures. These result in a weak polar stratospheric response to climate change (Mitchell et al., 2012a, Ayarzagüena et al., 2013). Consequently, individual models yield different future projections of SSW changes, depending on the relative importance of these competing effects in each model. Hence, any result obtained with a single model needs to be taken with much caution.

Another potential explanation for the discrepancies stems from the criterion chosen for the identification of SSWs. As shown in Butler et al. (2015), the identification of SSWs is sensitive to the method used. It was found to strongly depend on the meteorological variable chosen for analysis, and also on whether the identification criterion entails total fields and a fixed threshold (absolute criterion), or anomalies relative to a changing climatology (relative criterion). For instance, the traditional criterion of the World Meteorological Criterion (hereafter WMO criterion, McInturff, 1978) requires the reversal of both zonal-mean zonal wind at 60°N and 10hPa and the meridional gradient of zonal mean temperature between 60°N and the pole at the same level. This criterion was empirically developed given the observations in recent decades and was applied in historical stratospheric analyses (e.g., Labitzke, 1981). Recent studies have continued using the WMO criterion although many of them have only imposed the reversal of the wind for the SSW identification (e.g., Charlton and Polvani, 2007). Because of its simplicity and its dynamical insight, WMO criterion or even its recent simplified version is the most commonly used criterion in modelling studies as well. However, such an absolute metric might suffer from model biases in the polar vortex climatology, or due to changes in this climatology in the future might lead to an inappropriate measure of the change in the polar stratospheric variability (McLandress and Shepherd, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2012a; Butler et al., 2015). An analysis with the Canadian Middle Atmosphere Model by McLandress and Shepherd (2009) showed that the frequency of SSWs may or may not change depending on the detection index.

The purpose of this study, therefore, is to revisit the question of possible future SSW changes taking these issues into consideration. Seeking a robust answer, we employ three different SSW identification criteria (both absolute and relative) and apply them uniformly to the output from 12 state-of-the-art climate models (contributing to the Chemistry Climate Model Initiative, CCMI). The interactive stratospheric chemistry present in all the CCMI models makes them the most realistic in terms of stratospheric processes, and in general, the CCMI models are improved compared to their counterparts which participated in the previous Chemistry Climate Model Validation-2 programme (CCMVal-2). In particular, several CCMI models are coupled to interactive ocean modules and the vertical resolution of many models (Morgenstern et al. 2017). The structure of the paper is as follows: In Section 2 the data and methodology used in the analysis are described. The main results are shown in Section 3, and Section 4 includes the discussion and the most important conclusions derived from the analysis.

2. Data and methodology

2.1. Data description

Our study is based on the analysis of the transient REF-C2 simulation of 12 CCMI models (cf. Table 1; for more details see Morgenstern et al., 2017). The REF-C2 runs extend from 1960 to 2099 or 2100 for most models (except for the IPSL-LMDZ-REPROBUS model that terminates the run in 2095), and include natural and anthropogenic forcings following the CCMI specifications (Eyring et al., 2013). In particular, GHG concentrations and surface mixing ratios of ozone depleting substances (ODS) are based on observations until 2000, and on the Representative Concentration Pathway 6.0 (RCP6.0, Meinshausen et al., 2011) and A1 (WMO, 2011) scenarios, respectively, from 2000 to 2100. Solar variability is included in most of the models. Depending on the characteristics and performance of the models, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO) are prescribed or internally generated. Future changes in frequency and other features of SSWs are obtained by comparing the last 40 winters of each run (denoted as “the future”) to the first 40 winters (denoted as “the past”). Unless otherwise stated, anomalies are calculated from the climatology of the corresponding 40-year period. A Student’s t-test is applied to determine if the future changes are statistically significant in all cases except for the duration of SSWs where we applied a Wilcoxon ranked-sum test. The performance of the models in reproducing SSWs characteristics for the past period (1960–2000) is assessed by comparing the models to the ERA-40 and JRA-55 reanalyses (Uppala et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2015). Both reanalyses extend back of 1979, covering the past period of our study. Among the few reanalyses that have available data in the pre-satellite era, ERA-40 and JRA-55 are the most suitable for middle atmosphere analyses because they have a higher top level and vertical resolution (Fujiwara et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Main characteristics relative to the models and their REF-C2 simulations used in this study.

| CCMI models | Model resolution | QBO | Solar variability | SSTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEOS-CCM | 2.5° x 2°, L72 (top:0.01hPa) |

Internally generated | No | Prescribed (CESM1) |

| CNRM-CCM | T42L60 (top: 0.07 hPa) | Internally generated | Yes | Prescribed (CNRM) |

| NIWA-UKCA | 3.75° x 2.5°, L60 (top: 84 km) | Internally generated | No | Coupled to ocean model |

| CCSRNIES-MIROC 3.2 | T42L34 (top: 0.012 hPa) | Nudged | Yes | Prescribed (MIROC 3.2) |

| IPSL-LMDZ-REPROBUS | 3.75° x 2.5°, L39 (top: 70 km) | Nudged | -- | Prescribed (SRES A1b IPSL) |

| ACCESS-CCM | 3.75° x 2.5°, L60 (top: 84 km) | Internally generated | No | Prescribed (HadGEM-ES2) |

| HadGEM3-ES | 1.875°x1.25°, L85 (top: 85 km) | Internally generated | Yes | Coupled to ocean model |

| SOCOL3 | T42L39 (top: 0.01hPa) | Nudged | Yes | Prescribed (CESM1(CAM5)) |

| MRI-ESM1r1 | TL159L80 (top: 0.01hPa) | Internally generated | Yes | Coupled to ocean model |

| EMAC-L47 | T42L47 (top: 0.01hPa) | Nudged | Yes | Prescribed (HadGEM2-ES) |

| EMAC-L90 | T42L90 (top: 0.01hPa) | Internally generated (slightly nudged) | Yes | Prescribed (HadGEM2-ES) |

| CMAM | T47L71 (top: 0.0575 hPa) | Internally generated | No | Prescribed (CanCM4) |

2.2. Criteria for the detection of SSWs

As the detection of SSWs is somewhat sensitive to the chosen criterion, we use three different criteria to ensure that the conclusions regarding future changes are the same irrespective of the metric. The criteria we use are described in Butler et al. (2015) and as follows.

1). WMO (World Meteorological Organization) criterion

SSWs are identified when the zonal-mean zonal wind at 10 hPa and 60°N and the zonal-mean temperature difference between 60°N and the pole at the same level reverse. Two events must be separated by at least 20 consecutive days of westerly winds. Only events from November to March are considered. Stratospheric final warmings are excluded by imposing at least 10 days with westerly winds after the occurrence of a SSW and before 30 April, to ensure the recovery of the polar vortex before its final breakup. The onset date of the event corresponds to the first day of the wind reversal.

2). Polar cap zonal wind reversal (u6090N)

SSWs are identified when the zonal wind at 10 hPa averaged over the polar cap (60°N-90°N) reverses. The separation of events and the exclusion of stratospheric final warmings are done in the same way as for the WMO criterion.

3). Polar cap 10hPa geopotential (ZPOL)

SSWs are identified based on the polar cap standardized anomalies of 10 hPa geopotential height. The anomalies are detrended and computed following Gerber et al. (2010). A SSW is detected if the anomalies exceed three standard deviations of the climatological January to March geopotential height (Thompson et al. 2002).

Note that WMO and u6090N Note that WMO and u6090N are absolute SSWs criteria, whereas ZPOL is a relative SSW one.

2.2. Other SSW characteristics

Beyond their frequency, we also study if the other key characteristics of SSWs, such as duration and tropospheric forcing, will change in the future. The considered events in all features are those identified by the WMO criterion, because it is a popular criterion and, as will be shown later, the conclusions relative to the frequency results are not different from those obtained for the other two criteria. These are the metrics/diagnostics applied:

1. Duration:

The duration of the events is computed by the number of consecutive days of easterly wind regime at 60°N and 10 hPa as in Charlton et al. (2007).

2. Tropospheric forcing

The analysis of the tropospheric forcing is based on the evolution of the anomalous eddy heat flux at 100 hPa averaged between 45° and 75°N (aHF100) before and after the occurrence of SSWs. aHF100 is a measure of the injection of tropospheric wave activity into the stratosphere (Hu and Tung, 2003).

3. Future changes in the main characteristics of SSWs

3.1. Mean frequency

We start by considering the frequency of SSWs, and whether it is projected to change as a consequence of anthropogenic forcings. For this purpose, we have identified SSWs in the 12 models listed in Table 1, for the past and future periods, according to the three identification criteria presented in Section 2.2. Figure 1 shows the mean frequency of SSWs for each case.

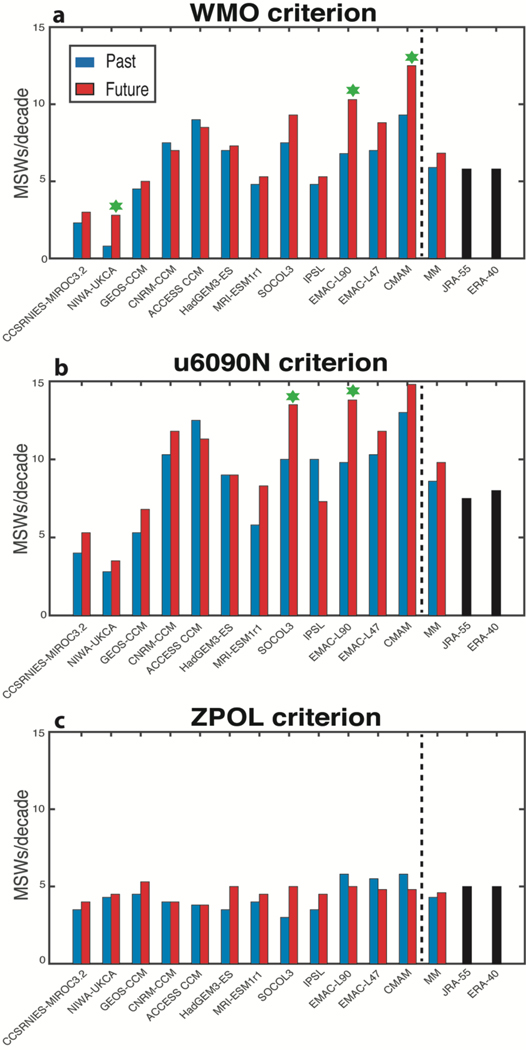

Figure 1:

(a) Mean frequency of major stratospheric warmings per decade for the past (blue bars) and the future (red bars) for all models, the multimodel mean (MM) and JRA-55 and ERA-40 reanalyses (black bars) according to the WMO criterion. (b) – (c) Same as (a) but for the u6090N and ZPOL, respectively. Green stars on top of the future bar denote a statistically significant change in the frequency of SSWs in the future at the 95% confidence level.

In spite of some differences among the criteria, there appears to be a suggestion of a small increase in frequency in the multimodel mean (hereafter MM), but this tendency is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level for any of the criteria, either absolute or relative. Also, while most models show a small increase in the frequency of SSWs in the future (10 of 12 models for the WMO criterion; 9 of 12 in the u6090N criterion; and 7 of 12 for the ZPOL), most of those changes are not statistically significant. Specifically, none of the models displays a statistically significant future change for the relative criterion (ZPOL) (Fig. 1c), only 3 out of 12 models show a significant increase for the WMO criterion (NIWA-UKCA, EMAC-L90 and CMAM) (Fig. 1a), and only 2 out of 12 models for the u6090N criterion (SOCOL3, EMAC-L90) (Fig. 1b). It is, however, important to note that the NIWA-UKCA and CMAM models do not simulate a realistic frequency of SSWs in comparison with reanalyses in the current climate, so they may not be a reliable indicator of a possible future change. Additionally, none of the four models (NIWA-UKCA, SOCOL3, EMAC-L90 and CMAM) shows an increase in SSWs for the three criteria simultaneously, indicating the lack of consistency for those models across the different methods. This confirms the absence of a robust future change in the frequency of SSWs.

A further comparison of the results for AA further comparison of the results for the different criteria in the past period confirms the findings of previous studies (e.g. McLandress and Shepherd, 2009) which showed that models’ biases in mean state and variability affect the frequency values for the absolute criteria, since the different models show a wide range of SSW frequency values in the past period (see Fig. S1).

For instance, CCSRNIES-MIROC3.2 and NIWA-UKCA show very low SSW frequencies in agreement with the fact that the polar vortex in these models is much stronger than in the reanalyses, and the opposite is seen for ACCESS CCM, CMAM and CNRM-CCM (Fig S2). Note the good agreement between the JRA-55 and ERA-40 reanalyses. Conversely, SSW frequencies computed with the relative ZPOL criterion are more similar across the models, as they are less affected by climatological model biases. Interestingly, note how the values for the relative criterion are somewhat lower in models than in the reanalyses. Since the threshold for selecting events is based on observations, this suggests that the models may be underestimating the variability of the Arctic polar stratosphere.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that nearly identical results to the ones obtained with the WMO criterion are found, in both the past and future periods, when only the reversal of the wind at 60°N and 10hPa (Charlton and Polvani, 2007) is used as the identification criterion. It is reassuring to report that the additional temperature constraint imposed in the WMO criterion does not significantly alter the frequency of SSWs, even for the future warmer climates. This means that most recent studies, which have used the simpler method and considered the reversal of the wind as the sole quantity for identifying SSWs, would have certainly reached the same conclusions had they used the more precise WMO criterion, and can thus be considered valid.

3.2. Duration

Next, we turn to the duration of SSWs, for which the results are shown in Fig. 2, for the past and future. In each period, we notice a considerable spread across the models; nonetheless, the MM value for the past period falls within the interval of reanalyses values ±1.5 standard deviation. Note, however, the variability within each model is larger than that across the models. This is particularly true for the NIWA-UKCA and CCSRNIES-MIROC3.2 models, possibly as a consequence of the low number of SSWs simulated by these two models. MRI-ESM1r1 also shows a large variability in SSW duration, but only in the past period.

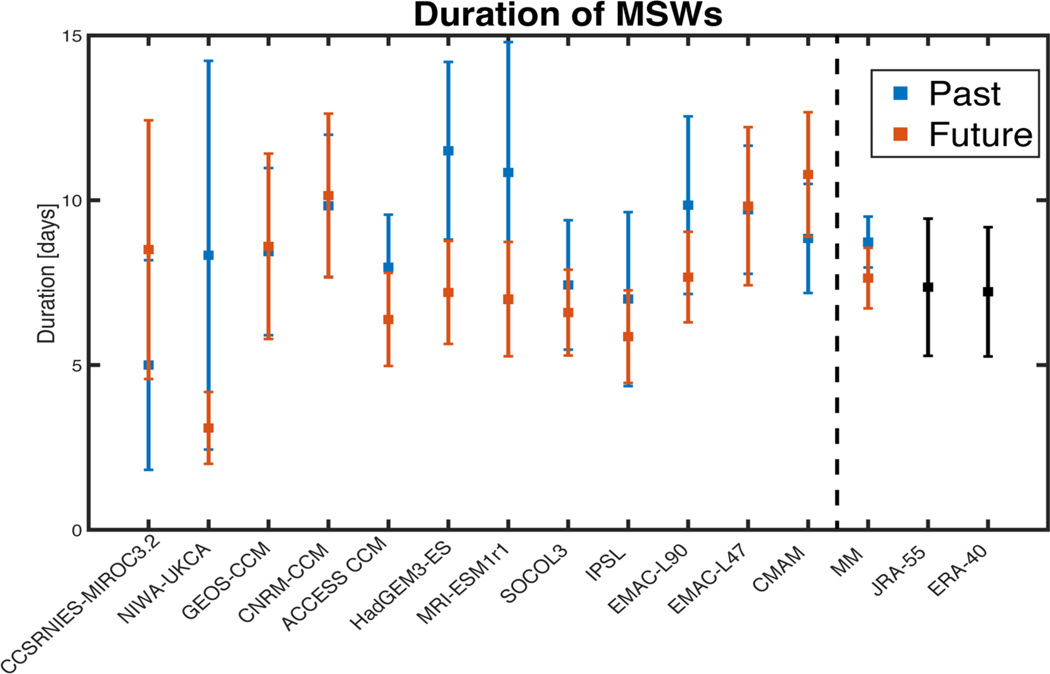

Figure 2.

Duration of SSWs (in days) in each model for both periods of study. Bars denote ±1.5 standard deviation divided by the square root of the number of events and green stars indicate future values that are statistically significantly different from the past ones at the 95% confidence level.

The key message from Fig. 2 is that the duration of SSWs does not change in the future, using the canonical 95% confidence level. Nevertheless, as in the case of the mean frequency, more than half of the models (7 out of 12) agree on the sign of the future change in the SSW duration (they indicate that it will be slightly shorter), but this change in the MM is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

3.3. Tropospheric forcing

Since SSWs are usually triggered by anomalously high tropospheric wave activity entering the stratosphere in the weeks preceding the events (Matsuno, 1971; Polvani and Waugh 2004), we have analyzed the possible future changes in the injection of wave activity (aHF100) in the course of the occurrence of these events for the MM (Fig.3). The results do not show a statistically significant change in any aspect of the anomalous wave activity preceding SSWs in the MM and in the individual models (not shown). In particular, neither the strong peak of aHF100 of the MM in the 10 days prior to the occurrence of events nor the general time evolution of the aHF100 are projected to change in the future (Fig.3a). Hence the common, but not statistically significant, trend of models towards shorter future SSWs mentioned above cannot be explained by changes in tropospheric forcing. Additionally, when examining the two first zonal wavenumber components of the anomalous HF100, no significant future changes are found either (Fig.3b).

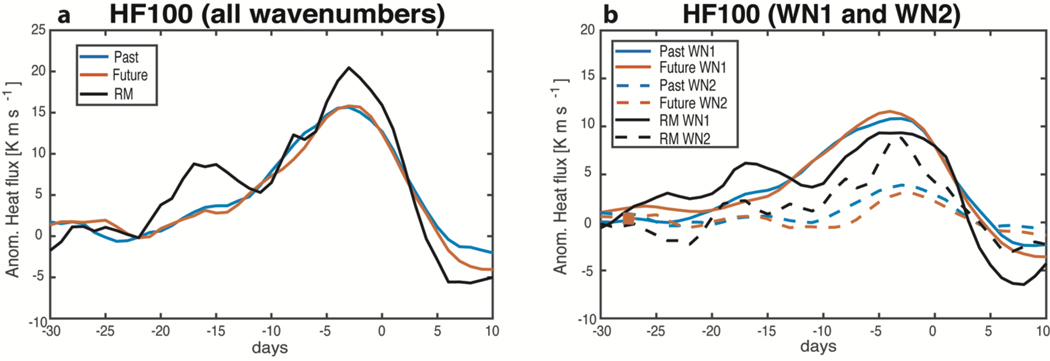

Figure 3.

(a) Multimodel mean of anomalous heat flux (K m s−1) at 100hPa averaged over 45°N-75°N from 30 days before until 10 days after the occurrence of SSWs. (b) Same as (a) but for WN1 (solid lines) and WN2 (dashed lines) wave components. Thick lines denote statistically significant future values different from the past ones at the 95% confidence level. RM stands for the Reanalyses (JRA-55 and ERA-40) Mean.

Model projections of future aHF100 are reliable because models are able to simulate the tropospheric forcing of these events reasonably well (Fig.3). Only a few discrepancies can be seen between the MM and the mean of JRA-55 and ERA-40 reanalyses (Reanalyses Mean, RM, black curve). Note that we include the average of JRA-55 and ERA-40 because they show very similar results. One of the discrepancies between MM and RM is that the strong peak in aHF100 in the 5 days prior to the occurrence of SSWs is weaker in the models than in observations. The reanalyses also show a secondary peak of aHF100 between −20 and - 10 days that does not appear in the MM. Additionally, the contribution of the wavenumber 1 (WN1) component to the strongest wave pulse is similar or even stronger than in the reanalyses (Fig.3b), but the wavenumber 2 (WN2) in the models is much weaker than in the RM. This explains the weaker total value of aHF100 in the MM than in the RM. Nevertheless, the RM is only one realization averaged over 40years and the MM corresponds to the average over many more realizations. Thus, the multi-model/individual realization spread possibly account for at least partially these two mismatches between MM and RM. In any case, the models show no changes between the past and the future.

4. Discussion and conclusions

We have revisited the question of whether SSWs will change in the future, analysing 12 state-of-the-art stratosphere resolving models that participated in CCMI. To obtain robust results, we have used three different identification methods (two absolute and one relative) and have applied them consistently across all 12 models. In summary, our analysis reveals that:

No statistically significant changes in the frequency of occurrence of SSWs are to be expected in the coming decades. This result is robust, as it is obtained with three different identification criteria.

Other features of SSWs, such as their duration and the tropospheric precursor wave fluxes, do not change in the future either in the model simulations, in agreement with other studies such as McLandress and Shepherd (2009) or Bell et al. (2010).

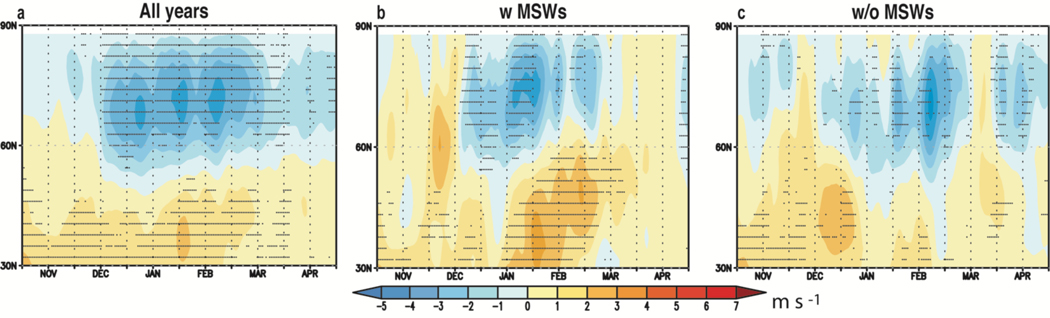

Despite the lack of statistical significant changes in the frequency of SSWs, both the MM and the majority of the models analysed show a slight increase across all criteria. A similar result was reported by Kim et al. (2017), who analysed the change in SSW frequency in some CMIP5 models by identifying the events based either on the reversal of the wind or the vortex deceleration. Looking at changes in the daily climatology of the zonal mean zonal wind at 10 hPa (Figs. 4a and S3), the MM and individual model simulations also provide a consistent picture, with a robust weakening of the polar night jet (PNJ) from mid-December until mid-March, the deceleration being particularly strong between mid-December and mid-February; this is in agreement with previous CMIP5 results (Manzini et al., 2014).This deceleration is, however, only statistically significant in less than half of the models, explaining that we do not find a significant change in the tropospheric forcing of SSWs (Fig. S3). To determine whether these changes in the climatology of wintertime PNJ might be associated with changes in SSWs frequency, the future-minus-past difference plots of the climatological wind are shown separately for winters with and without SSWs (Fig. 4b and c, respectively). We find a weakening of the PNJ in midwinter in both cases and hence, the future deceleration of the PNJ is not strictly a consequence of a higher frequency of SSWs. This deceleration might be related though to a general increase in the total stratospheric variability that, in the case of winters without SSWs, would correspond to a higher frequency of minor warmings. However, this possibility is unlikely because we have not identified a robust future increase in the standard deviation of zonal-mean zonal wind at 10hPa across the models (not shown). What could be possible is that the future deceleration of the PNJ might explain the statistically significant increase in SSWs in a few models using the absolute criteria. In any case, these signals are small and it is nearly impossible to untangle the cause and the effect, as these changes occur simultaneously.

Figure 4.

(a) Multimodel mean of future-minus-past differences in the daily climatology of 5-day running mean of zonal mean zonal wind at 10 hPa. (b) Same as (a) but only for winters with SSWs. (c) Same as (a) but for winters without SSWs. Shading interval: 1 m s−1. Dots indicate where at least 75% of the models coincide in sign with the multimodel mean.

More importantly our findings dispel, to a large degree, the confusion in the literature regarding future SSW changes, and suggest that previous reports of significant changes are likely to be artefacts, caused by biases associated with individual models, or by flaws in the identification methods used (or both). Note that although the key finding of our study – i.e. that anthropogenic forcings will not affect SSWs over the 21st century – is a null result, it is by no means uninteresting. Just to offer one example: Kang and Tziperman (2017) have recently proposed that future changes in the Madden Julian Oscillation (which are expected to occur with increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere) will cause an increased occurrence of SSWs. While their conclusion may be correct, our findings indicate that it can be misleading to project changes in the SSWs on the basis of a single mechanism: the complexity of the climate system is such that multiple mechanisms may be at play, with likely opposite effects which may result in change in SSWs that are not statistically significant.

One may argue that the lack of a statistically significant future change in our study could be explained, at least partially by the high interannual variability of the boreal polar stratosphere in 40-year periods (e.g., Langematz and Kunze, 2006), or perhaps by the natural variability on longer time-scales coming from other subcomponents of the climate system (e.g.: Schimanke et al., 2011). As shown in a recent paper, 10 identically forced model integrations over the 50-year period 1952–2003 exhibit great differences in the number of SSWs (Polvani et al, 2017), and these differences are solely due to internal variability. This means that the 40 years of observations at our disposal may not represent the mean of a distribution but could be an outlier. Needless to say, we have no means to determine whether this is the case, as we do not have long enough observations.

Another argument against the non-significant future changes is that the climate change scenario of our runs (RCP6.0) is not extreme enough to produce a significant signal in the frequency and duration of SSWs. Thus, one may think that this signal might become significant under the RCP8.5 scenario. Although we cannot rule out this possibility, it seems improbable based on a similar lack of significance in the results documented for that extreme scenario by previous studies (Mitchell et al. 2012a; Ayarzagüena et al. 2013, Hansen et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2017). Nevertheless, it would be hard to verify the hypothesis because of the low number of CCMI RCP8.5 simulations.

Finally, in the last years much activity has been devoted to search for novel criteria for the identification of SSWs (Butler et al., 2015). One of the reasons given to justify the implementation of a new metrics was that the traditional WMO criterion was not appropriate for modelling studies, as it was based on observational parameters, such as the location of the polar night jet. However, our results show that this criterion performs well under a changing climate, provided models are able to reproduce correctly the past stratospheric variability. Thus, considering the good agreement among the three criteria used here on the lack of change in future SSWs, and given the dynamical implications for the propagation of planetary waves into the stratosphere, we suggest that the WMO criterion is appropriate for the study of SSWs in the future if the model can represent well the stratospheric variability. Futhermore, since the simplest (and most commonly used) criterion, involving only the zonal winds (Charlton and Polvani, 2007), yields identical results as the WMO criterion, one could argue that the simplest method may suffice in most cases for the study of SSWs, and that more complex criteria might not be worth the trouble. A similar conclusion was reached, independently, by Butler and Gerber (2018) who methodically assessed different metrics and concluded that the simplest algorithm is within the optimal range.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the modeling groups for making their simulations available for this analysis, the joint WCRP SPARC/IGAC Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) for organizing and coordinating the model data analysis activity, and the British Atmospheric Data Centre (BADC) for collecting and archiving the CCMI model output. BA was funded by the European Project 603557-STRATOCLIM under the FP7-ENV.2013.6.1–2 programme and “Ayudas para la contratación de personal postdoctoral en formación en docencia e investigación en departamentos de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid”. LMP is grateful for the continued support of the US National Science Foundation. The work of NB, SCH, and FOC was supported by the Joint BEIS/Defra Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme (GA01101). NB and SCH were supported by the European Community within the StratoClim project (Grant 603557). OM and GZ acknowledge the UK Met Office for use of the MetUM. This research was supported by the NZ Government’s Strategic Science Investment Fund (SSIF) through the NIWA programme CACV. OM acknowledges funding by the New Zealand Royal Society Marsden Fund (grant 12-NIW-006) and by the Deep South National Science Challenge (http://www.deepsouthchallenge.co.nz). The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of NeSI high-performance computing facilities to the results of this research. New Zealand’s national facilities are provided by the New Zealand eScience Infrastructure (NeSI) and funded jointly by NeSI’s collaborator institutions and through the Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment’s Research Infrastructure programme (https://www.nesi.org.nz). The EMAC simulations have been performed at the German Climate Computing Centre (DKRZ) through support from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). DKRZ and its scientific steering committee are gratefully acknowledged for providing the HPC and data archiving resources for the consortial project ESCiMo (Earth System Chemistry integrated Modelling). CCSRNIES’s research was supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Funds of the Ministry of the Environment (2–1303) and Environment Restoration and Conservation Agency (2–1709), Japan, and computations were performed on NEC-SX9/A(ECO) and NEC SX-ACE computers at the CGER, NIES.

References

- Ayarzagüena B, Langematz U, Meul S, Oberländer S, Abalichin J, and Kubin A: The role of climate change and ozone recovery for the future timing of major stratospheric warmings, Geophys. Res. Lett, 40, 2460–2465, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MP and Dunkerton TJ: Stratospheric harbingers of anomalous weather regimes, Science, 294, 581–583, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CJ, Gray LJ, and Kettleborough J: Changes in Northern Hemisphere stratospheric variability under increased CO2 concentrations, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc, 136, 1181–1190, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butchart N, Austin J, Knight JR, Scaife AA, and Gallani ML: The response of the stratospheric climate to projected changes in the concentrations of well-mixed greenhouse gases from 1992 to 2015, J. Climate, 13, 2142–2159, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AH, Seidel DJ, Hardiman SC, Butchart N, Birner T, and Match A: Defining sudden stratospheric warmings, Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc, 96, 1913–1928, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AH, Gerber EP: Optimizing the definition of a sudden stratospheric warming. J. Climate, in press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton AJ, and Polvani LM: A new look at stratospheric sudden warmings. Part I: Climatology and modelling benchmarks, J. Climate, 20, 449–469, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton AJ, Polvani LM, Perlwitz J, Sassi F, Manzini E, Shibata K, Pawson S, Nielsen JE, and Rind D: A new look at stratospheric sudden warmings. Part II: Evaluation of numerical model simulations, J. Climate, 20, 470–488, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton-Perez AJ, Polvani LM, Austin J, and Li F: The frequency and dynamics of stratospheric sudden warmings in the 21st century, J. Geophys. Res, 113, D16116, doi: 10.1029/2007JD009571, 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyring V, Lamarque J-F, Hess P, Arfeuille F, Bowman K, Chipperfield MP, Duncan B, Fiore A, Gettelman A, Giorgetta MA, Granier C, Hegglin M, Kinnison D, Kunze M, Langematz U, Luo B, Martin R, Matthes K, Newman PA, Peter T, Robock A, Ryerson T, Saiz-Lopez A, Salawitch R, Schultz M, Shepherd TG, Shindell D, Staehelin J, Tegtmeier S, Thomason L, Tilmes S, Vernier J–P, Waugh DW, and Young PJ,: Overview of IGAC/SPARC Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) community simulations in support of upcoming ozone and climate assessments, SPARC Newsletter, 40, 48–66, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M, et al. : Introduction to the SPARC Reanalysis Intercomparison Project (S-RIP) and overview of the reanalysis systems, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 17, 1417–1452, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber EP, Baldwin MP, Akiyoshi H, Austin J, Bekki S, Braesicke P, Butchart N, Chipperfield M, Dameris M, Dhomse S, Frith SM, Garcia RR, Garny H, Getterlman A, Hardiman SC, Karpechko A, Marchand M, Morgenstern O, Nielsen JE, Pawson S, Peter T, Plummer DA, Pyle JA, Rozanov E, Scinnocca JF, Shepherd TG, and Smale D: Stratosphere-troposphere coupling and annular mode variability in chemistry-climate models, J. Geophys. Res, 115, doi: 10.1029/2009JD013770, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen F, Matthes K, Petrick C, and Wang W: The influence of natural and anthropogenic factors on major stratospheric sudden warmings, J. Geophys. Res, 119, 8117–8136, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, and Tung KK: Possible ozone-induced long-term changes in planetary wave activity in late winter, J. Climate, 16, 3027–3038, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kang W. and Tziperman E: More frequent sudden stratospheric warming events due to enhanced MJO forcing expected in a warmer climate. Journal of Climate, 30, 8727–8743, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Son S-W, Gerber EP, and Park H-S: Defining sudden stratospheric warming in climate models: Accounting for biases in model climatologies, J. Climate, 30, 5529–5546, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S. et al. : The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics, J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 93, 5–48, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Labitzke K: Stratospheric-mesospheric midwinter disturbances: A summary of observed characteristics, J. Geophys. Res 86:9665–9678, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Labitzke K, and Naujokat B: The lower arctic stratosphere in winter since 1952, SPARC Newsl., 15, 11–14, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Langematz U, and Kunze M: An update on dynamical changes in the Arctic and Antarctic stratospheric polar vortices, Clim. Dyn, 27, 647–660, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouf JF, Cariolle D, Geleyn J-F, Timbal B.: Response of the Météo-France climate model to changes in CO2 and sea surface temperature, Clim. Dyn, 9, 345–362, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini E, Karpechko AY, Anstey J, Baldwin MP, Black RX, Cagnazzo C, Calvo N, Charlton-Perez A, Christiansen B, Davini P, Gerber E, Giorgetta M, Gray L, Hardiman SC, Lee Y-Y, Marsh DR, McDaniel BA, Purich A, Scaife AA, Shindell D, Son S–W, Watanabe S, and Zappa G: Northern winter climate change: Assessment of uncertainty in CMIP5 projections related to stratosphere-troposphere coupling, J. Geophys. Res, 119, 7979–7998, doi: 10.1002/2013JD021403, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno T: A dynamical model of stratospheric sudden warming, J. Atmos. Sci, 28, 1479–1494, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- McLandress C, and Shepherd TG: Impact of climate change on stratospheric sudden warmings as simulated by the Canadian Middle Atmosphere Model, J. Climate, 22, 5449–5463, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McInturff RM, Ed.: Stratospheric warmings:Synoptic, dynamic and general-circulation aspects. NASA Reference Publ. NASA-RP-1017, 174 pp, 1978[Available online at http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19780010687.pdf.] [Google Scholar]

- Meinshausen M, Smith SJ, Calvin K, Daniel JS, Kainuma MLT, Lamarque J-F, Matsumoto K, Montzka SA, Raper SCB, Riahi K, Thomson A, Velders GJM, and van Vuuren DPP: The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300, Climatic Change, 109, 213–241, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DM, Osprey SM, Gray LJ, Butchart N, Hardiman SC, Charlton-Perez AJ, and Watson P: The effect of climate change on the variability of the Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex, J. Atmos. Sci, 69, 2608–2618, 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DM, Charlton-Perez AJ, Gray LJ, Akiyoshi H, Butchart N, Hardiman SC, Morgenstern O, Nakamura T, Rozanov E, Shibata K, Smale D, and Yamashita Y: The nature of Arctic polar vortices in chemistry-climate models, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc, 138, 1681–1691, 2012b. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern O, Hegglin MI, Rozanov E, O’Connor FM, Abraham NL, Akiyoshi H, Archibald AT, Bekki S, Butchart N, Chipperfield MP, Deushi M, Dhomse SS, Garcia RR, Hardiman SC, Horowitz LW, Jöckel P, Josse B, Kinnison D, Lin M, Mancini E, Manyin ME, Marchand M, Marécal V, Michou M, Oman LD, Pitari G, Plummer DA, Revell LE, Saint-Martin D, Schofield R, Stenke A, Stone K, Sudo K, Tanaka TY, Tilmes S, Yamashita Y, Yoshida K, and Zeng G: Review of the global models used within the phase 1 of the Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI), Geosci. Model Dev, 10, 639–671, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Polvani LM, Waugh DW: Upward wave activity flux as a precursor to extreme stratospheric events and subsequent anomalous surface weather regimes, J. Climate, 17, 3548–3554, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Polvani LM, Sun L, Butler AH, Richter JH and Deser C: Distinguishing stratospheric sudden warmings from ENSO as key drivers of wintertime climate variability over the North Atlantic and Eurasia, J. Climate, 30, 1959–1969, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rind D, Shindell D, Lonergan P, Balachandran NK: Climate change and the middle atmosphere. Part III: The doubled CO2 climate revisited, J. Climate, 11, 876–894, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schimanke S, Körper J, Spangehl T, and Cubasch U: Multi-decadal variability of sudden stratospheric warmings in an AOGCM, Geophys. Res. Lett, 38, L01801, doi: 10.1029/2010GL045756, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmond M, Scinocca JF, Kharin VV, and Shepherd TG: Enhanced seasonal forecast skill following stratospheric sudden warmings, Nat. Geos, 6, 98–102, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SPARC CCMVal, SPARC Report on the Evaluation of Chemistry-Climate Models, edited by Eyring V, Shepherd TG, and Waugh DW, SPARC Report No. 5, WCRP-132, WMO/TD-No. 1526, pp 109–148, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DWJ, Baldwin MP, and Wallace JM: Stratospheric connection to Northern Hemisphere wintertime weather: Implications for prediction, J. Climate, 15, 1421–1428, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uppala SM, et al. : The ERA-40 re-analysis, Q. J. R. Meteor. Soc, 131, 2961–3012, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- WMO (World Meteorological Organization): Scientific assessment of ozone depletion: 2010, Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.