Abstract

Background

Small open reading frames (smORF/sORFs) that encode short protein sequences are often overlooked during the standard gene prediction process thus leading to many sORFs being left undiscovered and/or misannotated. For many genomes, a second round of sORF targeted gene prediction can complement the existing annotation. In this study, we specifically targeted the identification of ORFs encoding for 80 amino acid residues or less from 31 fungal genomes. We then compared the predicted sORFs and analysed those that are highly conserved among the genomes.

Results

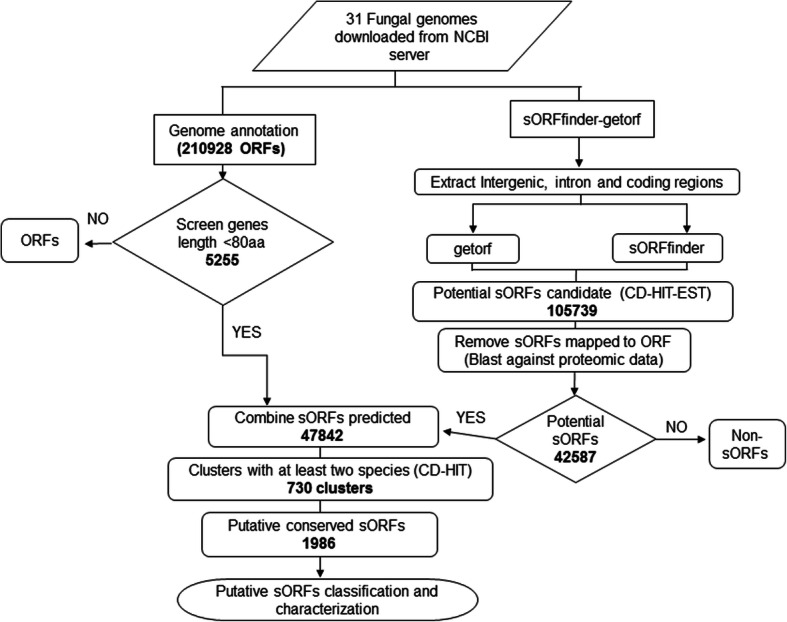

A first set of sORFs was identified from existing annotations that fitted the maximum of 80 residues criterion. A second set was predicted using parameters that specifically searched for ORF candidates of 80 codons or less in the exonic, intronic and intergenic sequences of the subject genomes. A total of 1986 conserved sORFs were predicted and characterized.

Conclusions

It is evident that numerous open reading frames that could potentially encode for polypeptides consisting of 80 amino acid residues or less are overlooked during standard gene prediction and annotation. From our results, additional targeted reannotation of genomes is clearly able to complement standard genome annotation to identify sORFs. Due to the lack of, and limitations with experimental validation, we propose that a simple conservation analysis can provide an acceptable means of ensuring that the predicted sORFs are sufficiently clear of gene prediction artefacts.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12859-018-2550-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Small open Reading frames, sORFs, smORF, Conserved, Fungal

Background

Small open reading frames (smORF) are sequences that potentially encode for proteins but are shorter than other more commonly translated genomic DNA sequences [1]. Such protein sequences can theoretically range from a minimum of two to ~ 100 residues. Various values have been reported for what can be acceptable as the limits to be a small and functional protein. The problem of determining what constitutes the minimum number of codons to be considered as protein coding has been discussed since the earliest genome sequences for Saccharomyces cerevisiae were published [2, 3]. In addition to the term smORF, these sequences have also been referred to as short open reading frames (sORFs) and the proteins that they encode have at times been referred to as microproteins.

Despite the term sORF turning up only in more recent literature, the existence of genes that code for proteins of 150 residues and less have been known for more than three decades. Functional sORFs have been identified in a wide range of organisms from prokaryotes to humans. The Sda protein (46 residues) found in Bacillus subtilis is known to inhibit sporulation by preventing the activation of a required transcription factor [4, 5]. Proteins such as TAL (11 residues), found in Drosophila melanogaster, are known to be important for leg development [6, 7]. The Cg-1 protein (< 33 amino acids) is involved in controlling tomato-nematode interaction [8]. In Homo sapiens, the humanin (24 amino acids) protein is involved in mitochondria-nuclear retrograde signalling that controls apoptosis [9, 10]. Possibly the smallest ORF reported to date encodes a six residue polypeptide – MAGDIS; this ORF is referred to as the upstream open reading frame (uORF) in the mRNA of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC), a key enzyme in the polyamine biosynthesis pathway [11].

As genome sequencing capabilities steadily progressed from the late 90s, through the 2000s to the present, many studies have identified and annotated sORFs directly from genome sequence data [12]. Various reports of sORFs discovered from such efforts have been published such as in Escherichia coli (15–20 amino acids) [13]; in yeast - Saccharomyces cerevisiae (less than 100 amino acids) [12, 14]; in plants - Arabidopsis thaliana (100–150 amino aicds) [15] and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (less than 80 amino acids) [16]; in insects - Drosophila (less than 100 amino acids) [17]; in mouse (less than 100 amino acids) [18] and in human (less than 100 amino acids) [19]. More recently, Erpf and Fraser reviewed the diverse roles of sORF encoded peptides (less than 150 amino acids) in fungi [20].

Nevertheless, it has also been shown that many ORFs with lengths of 100 or less amino acids may have been missed during gene prediction from whole genome sequences because the gene prediction tools are tuned to ignore small genes perceived to be ‘junk’ or non-protein coding [21]. For example, the early genome annotations of S. cerevisiae had defined 100 residues and 150 residues as the minimum number to be encoded by an ORF thus in a way setting a parameter value for future gene predictions and annotation work [2, 3]. Perhaps as a consequence of such practices being integrated as part of standard gene prediction protocols, the number of sORFs that have been identified over the years has remained relatively small. Although the parameters for the gene prediction can be tweaked and changed in light of a better understanding regarding the existence of sORFs, the challenge of ascertaining that the annotated sORFs are indeed protein coding and not artefacts remains [17].

In this work, we have identified potential sORFs from fungal genomes by specifically repeating the gene prediction and annotation processes based on a residue length cutoff of 80 amino acids or less and specified the range of sORFs length distribution among homologs to avoid false positives. The cutoff of 80 residues was chosen as a simplistic means of selecting ORFs that were most likely to have been overlooked by previous gene predictions. The identification of 1986 putative predicted sORFs involved a large sequence dataset extracted from 31 fungal genome sequences with a total of 210,928 ORFs from existing gene prediction and annotation. The predicted sORFs were then compared to identify highly conserved examples within the fungal genomes dataset by adopting the assumption that such highly conserved sequences may code for common or even essential functions and are thus unlikely to be artefacts or randomly matched examples. This can potentially be a quick and inexpensive means of identifying subsets of sORFs that are classified as hypothetical proteins for experimental characterization.

Results

Identification of potential sORFs

The fungal genomes selected were required to have associated annotations for predicted genes thus limiting our dataset to only 31 genomes at the time the work was initiated. These annotations were utilized to identify 5255 sORFs genes that had already been identified in the original annotation to encode for a maximum of 80 amino acid residues. The ORF prediction process was then repeated for all 31 fungal genomes using the computer programs getorf [22, 23] and sORFfinder [24] as detailed in methods section. This process resulted in 16,156,945 sORFs identified by getorf and 902,110 found by sORFfinder. The results of both searches were overlapped to yield a consensus of 42,587 potential sORFs sequences encoding for 80 residues or less. The ORFs predicted by getorf with a cutoff of 240 nt were considered as genes that can either be a region that is free of STOP codons or a region that begins with a START codon and ends with a STOP codon [22, 23]. However, all the sORFs identified in this study have both START as well as STOP codons.

Characterization of the fungal conserved sORFs

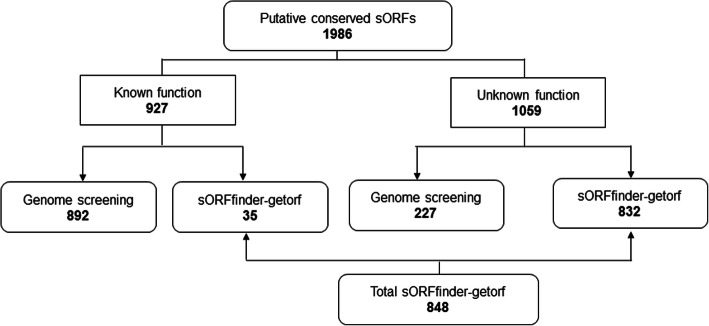

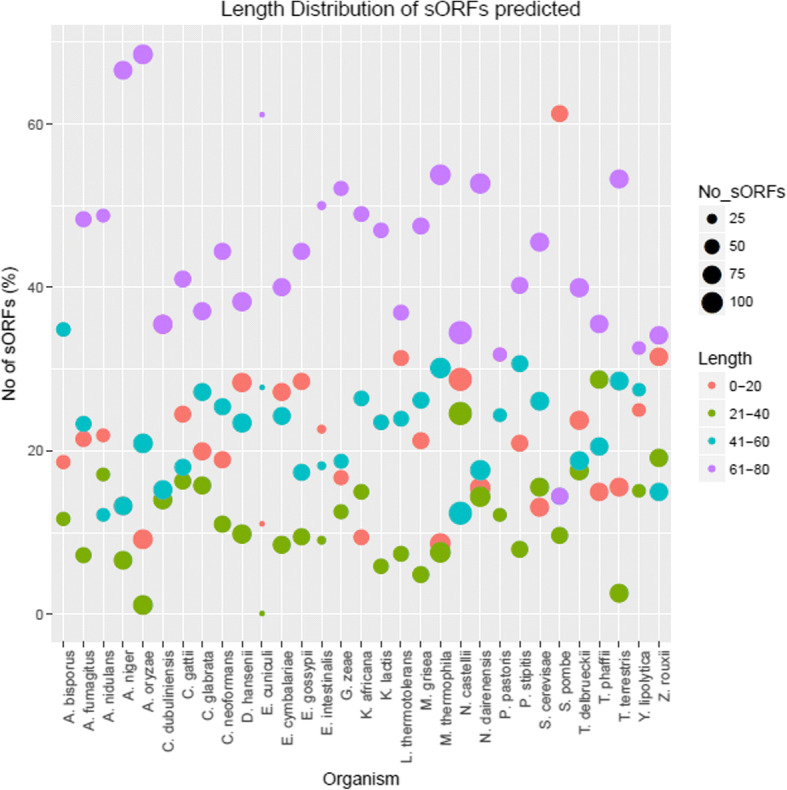

CD-HIT [25] clustering of the combined 47,842 potential sORFs at 70% sequence identity resulted in 730 sORFs clusters that comprised of 1986 sequences putatively conserved in at least two fungal species (Fig. 1). Four of the sORFs predicted have Kozak sequences based on an ORF integrity value that was derived by calculating their coding potential using CPC2 [26]. The majority of the sORFs predicted were in the under 40 residues range with the shortest sORF in this dataset being composed of only 11 amino acids (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Research workflow

Fig. 2.

Distribution of sORFs according to length for all 31 fungal genomes

The clustering based on 70% similarity of the 47,842 potential sORFs resulted in a total of 1986 putative sORFs that are conserved within at least two fungal species (Additional file 1). Among the 1986 putatively conserved sORFs, 927 have homologs with known functions (35 from the purpose built sORF prediction process; 892 from existing genome annotations) (Fig. 3). The remainder 1059 putatively conserved sORFs have uncharacterized functions and can be further divided into two categories: the first set - 23 sORFs with homologs outside of the 31 fungal genomes; and the second set - 1036 sORFs with no detectable sequence homologs outside of the 31 fungal genomes. The latter set can thus be considered as fungi specific sORFs.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of total of conserved sORFs across fungal genomes

Discussion

The standard gene prediction process may miss ORFs that encode for protein sequences of less than 100 residues [12, 27]. In order to address this, we carried out a two pronged approach using a dataset of 31 available fungal genomes to carry out: (i) identification of ORFs that have already been annotated to be below 80 residues in length and (ii) repeating the gene prediction process for each genome to specifically identify genes that encode for sORFs of 80 residues or less.

The bias of the parameter often used to predict genes that require a minimum of 100 codons may bypass the sequences in the intergenic spaces, especially when such regions are less than 100 residues in length, but yet they may actually encode for functional proteins of less than 80 residues. Intronic sequences may also hypothetically code for such sORFs. Therefore, these sequences were used as the target for sORF searches in this work. Predicted sORFs that were found to occur in multiple genomes were selected for further characterization. However, it was anticipated that such searches can return a large number of predicted genes, many of which could be artefacts of the search process itself. In order to address this, the pool of predicted sORFs were then compared to each other to find potentially homologous sequences within the predicted sORFs dataset. It is expected that such short sequences that are conserved in several genomes can be assumed to be of functional importance and thus not an artefact of the gene prediction process, especially more so if those sequences were also extracted from the intronic regions as was the case in this study.

At the time this work was initiated, 31 fungal genomes were selected because they had relatively complete genome sequences and had accompanying annotations. All the selected genomes were from the kingdom fungi and from various phyla including Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Microsporidia (Table 1). Due to this diversity, we therefore believe that the workflow developed would be widely applicable for all fungi and possibly for other kingdoms as well.

Table 1.

List of sORFs predicted from the whole genome and intergenic regions of fungal genomes

| Microorganisms (yeast/fungi) | Phylum | Genome size (Mb) | Scaffolds(sc)/ Chromosomes | Intergenic region | Intron | ORF | sORFs from genome annotation | sORF from ab initio prediction | Total sORFs predicted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GetORF | sORFfinder | Combined 1st & 2nd approached | sORFs match ORF homolog | sORFs ab initio predicted | ||||||||||

| Genome | Intergenic | |||||||||||||

| Agaricus bisporus | Basidiomycetes | 30.78 | 29sc | 10,606 | 50,859 | 10,450 | 575 | 423,332 | 113,990 | 902,110 | 2808 | 1952 | 856 | 1431 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Ascomycetes | 29.39 | 16 | 9916 | 18,630 | 9630 | 180 | 329,750 | 644,099 | 746,886 | 6665 | 5212 | 1453 | 1633 |

| Aspergillus nidulans | Ascomycetes | 29.83 | 17 | 9410 | 25,192 | 9410 | 83 | 376,689 | 533,546 | 288,159 | 3031 | 1803 | 1228 | 1311 |

| Aspergillus niger | Ascomycetes | 38.50 | 20sc | 10,828 | 25,160 | 10,609 | 90 | 454,556 | 645,989 | 431,379 | 2950 | 1690 | 1260 | 1350 |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Ascomycetes | 37.91 | 27sc | 12,937 | 29,686 | 12,818 | 172 | 508,537 | 639,035 | 361,674 | 3336 | 2042 | 1294 | 1466 |

| Candida dubliniensis | Ascomycetes | 14.62 | 8 | 5499 | 169 | 5213 | 45 | 180,147 | 249,542 | 181,108 | 4591 | 2046 | 2545 | 2590 |

| Candida glabrata | Ascomycetes | 12.34 | 14 | 6580 | 33,084 | 6575 | 159 | 153,883 | 203,269 | 290,815 | 2593 | 1271 | 1322 | 1481 |

| Cryptococcus gattii | Basidiomycetes | 18.37 | 14 | 6617 | 34,336 | 6475 | 94 | 250,564 | 331,357 | 263,216 | 2447 | 1864 | 583 | 677 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Basidiomycetes | 2.50 | 14 | 6658 | 479 | 6290 | 110 | 254,930 | 329,135 | 247,268 | 2266 | 1673 | 593 | 703 |

| Debaryomyces hansenii | Ascomycetes | 2.25 | 8 | 2029 | 32 | 1996 | 300 | 153,782 | 190,959 | 165,774 | 4179 | 2540 | 1639 | 1939 |

| Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Microsporidia | 2.22 | 11 | 1892 | 14 | 1833 | 13 | 28,102 | 33,715 | 53,062 | 554 | 396 | 158 | 171 |

| Encephalitozoon intestinalis | Microsporidia | 2.19 | 11 | 4853 | 239 | 4434 | 18 | 26,156 | 28,950 | 54,302 | 543 | 412 | 131 | 149 |

| Eremothecium cymbalariae | Microsporidia | 9.67 | 8 | 5356 | 276 | 4776 | 61 | 119,153 | 153,876 | 171,154 | 3384 | 1865 | 1519 | 1580 |

| Eremothecium gossypii | Microsporidia | 9.12 | 8 | 11,624 | 25,808 | 11,628 | 80 | 94,967 | 117,788 | 121,934 | 3529 | 2265 | 1264 | 1344 |

| Gibberella zeae | Ascomycetes | 38.05 | 11 | 5649 | 1040 | 5378 | 104 | 488,905 | 698,951 | 151,211 | 4487 | 2265 | 1832 | 1936 |

| Kazachstania africana | Ascomycetes | 11.13 | 12 | 5649 | 1040 | 5378 | 88 | 144,748 | 186,855 | 141,681 | 1894 | 1247 | 647 | 735 |

| Kluyveromyces lactis | Ascomycetes | 10.73 | 7 | 5412 | 182 | 5085 | 73 | 139,746 | 182,755 | 81,044 | 3006 | 1636 | 1370 | 1443 |

| Lachancea thermotolerans | Ascomycetes | 10.39 | 8 | 5498 | 284 | 5091 | 53 | 114,598 | 145,278 | 155,291 | 3134 | 1628 | 1506 | 1559 |

| Magnaporthe grisea | Ascomycetes | 40.30 | 8 | 14,210 | 25,265 | 14,014 | 1105 | 506,420 | 699,033 | 217,609 | 4466 | 2735 | 1731 | 2836 |

| Myceliophthora thermophila | Ascomycetes | 38.74 | 7 | 9294 | 15,500 | 9099 | 419 | 343,719 | 540,155 | 140,855 | 4738 | 2547 | 2191 | 2610 |

| Naumovozyma castellii | Ascomycetes | 11.22 | 10 | 5870 | 203 | 5592 | 102 | 147,551 | 187,871 | 187,462 | 5691 | 3430 | 2261 | 2363 |

| Naumovozyma dairenensis | Ascomycetes | 13.53 | 12 | 6057 | 177 | 5772 | 99 | 185,531 | 251,917 | 231,996 | 2841 | 1323 | 1518 | 1617 |

| Pichia pastoris | Ascomycetes | 9.60 | 4 | 5040 | 578 | 5040 | 89 | 112,299 | 138,917 | 61,604 | 4161 | 2872 | 1289 | 1378 |

| Pichia stipitis | Ascomycetes | 15.44 | 8 | 5816 | 2567 | 5816 | 61 | 186,356 | 259,185 | 79,673 | 2146 | 1008 | 1138 | 1199 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Ascomycetes | 12.16 | 17 | 6349 | 366 | 5906 | 224 | 153,187 | 200,252 | 398,979 | 3478 | 2196 | 1282 | 1506 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Ascomycetes | 12.59 | 4 | 6991 | 3793 | 5133 | 124 | 165,857 | 165,864 | 33,542 | 6027 | 3304 | 2723 | 2847 |

| Tetrapisispora phaffii | Ascomycetes | 12.12 | 16 | 5460 | 141 | 5250 | 89 | 153,895 | 206,397 | 825,322 | 2959 | 1410 | 1549 | 1638 |

| Thielavia terrestris | Ascomycetes | 36.91 | 6 | 9958 | 17,290 | 9802 | 72 | 296,185 | 443,166 | 163,032 | 3291 | 1966 | 1325 | 1397 |

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | Ascomycetes | 9.22 | 8 | 5176 | 203 | 4972 | 402 | 113,250 | 138,118 | 509,930 | 4521 | 3074 | 1447 | 1849 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Ascomycetes | 20.55 | 7 | 7357 | 1120 | 6472 | 106 | 242,726 | 369,856 | 127,236 | 1594 | 456 | 1138 | 1244 |

| Zygosaccharomyces rouxii | Ascomycetes | 9.76 | 7 | 5332 | 166 | 4991 | 65 | 123,372 | 154,232 | 353,232 | 4429 | 2634 | 1795 | 1860 |

| TOTAL | 210,928 | 5255 | 6,972,893 | 9,184,052 | 902,110 | 105,739 | 42,587 | 47,842 | ||||||

The first approach merely involved identifying ORFs from the existing available annotations for sequences that fitted the maximum 80 residues criterion used for this study. This approach was dependent on parameters had been set by the annotators of the deposited data as the minimum number of codons that were to be considered as protein coding. The sORFs retrieved from this extraction provided a reference for what had already been identified. The second approach, which can be considered as the major feature of this work, involved repeating the gene prediction and annotation process by specifically identifying potential ORFs in the intronic, exonic and intergenic regions. We had opted to focus the searches on sequences extracted from the intronic and intergenic regions because a relatively high number of sORFs can be found within these regions as demonstrated by the discoveries of 3241 putative sORFs in the intergenic regions of Arabidopsis thaliana [28] and 15 sORFs in the intronic regions of Drosophila [29].

The sORF identification in the second approach involved the use of two computer programs, sORFfinder and getorf. The sORFfinder program was specifically designed to detect small ORFs. The getorf program, which is available as part of the emboss package, employs a less stringent approach that simply involves setting the sequence length parameter for genes to be below 240 nucleotides within the start to stop codons reading frame. In order to throw a wider net, we specifically included intronic and intergenic sequences as inputs for sORF identification. It is not unexpected that the output of both programs would contain false positives. In order to narrow down the selection, we had only selected outputs that were agreed on by both sORFfinder and our getorf runs at the 240 nt cap. This filtering was done in order to reduce the number of sequences for further characterization. It is however possible that true sORFs are present in the dataset that were predicted by only one of the programs and thus not investigated further as a part of this work. This is a clear limitation of the process that we had introduced as a means to acquire a more manageable number of sequences for further characterization.

The bypassing of sORFs that are located in the intergenic regions can occur during what is considered as the standard gene prediction process because these stretches of sequence only have sufficient length to encode for polypeptides that may be shorter than 100 residues [12, 27] and are thus overlooked as simply being non-coding filler sequences between two coding sequences. In order to address the possibility that a large number of sORFs in the intergenic regions may have been missed during a standard gene prediction process as demonstrated by the work of Hanada et al. that identified novel small open reading frames that were confirmed to at least be transcribed [28], our analysis also specifically targeted for the presence of sORFs in those sequences.

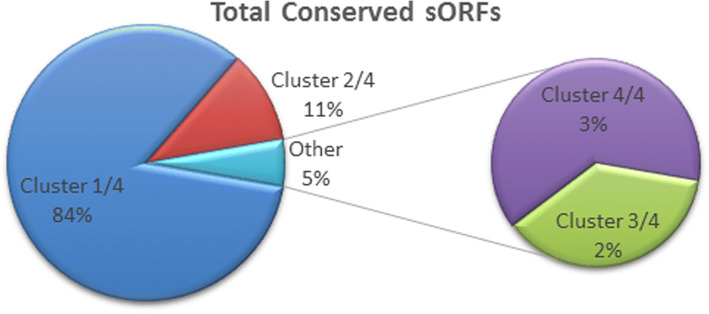

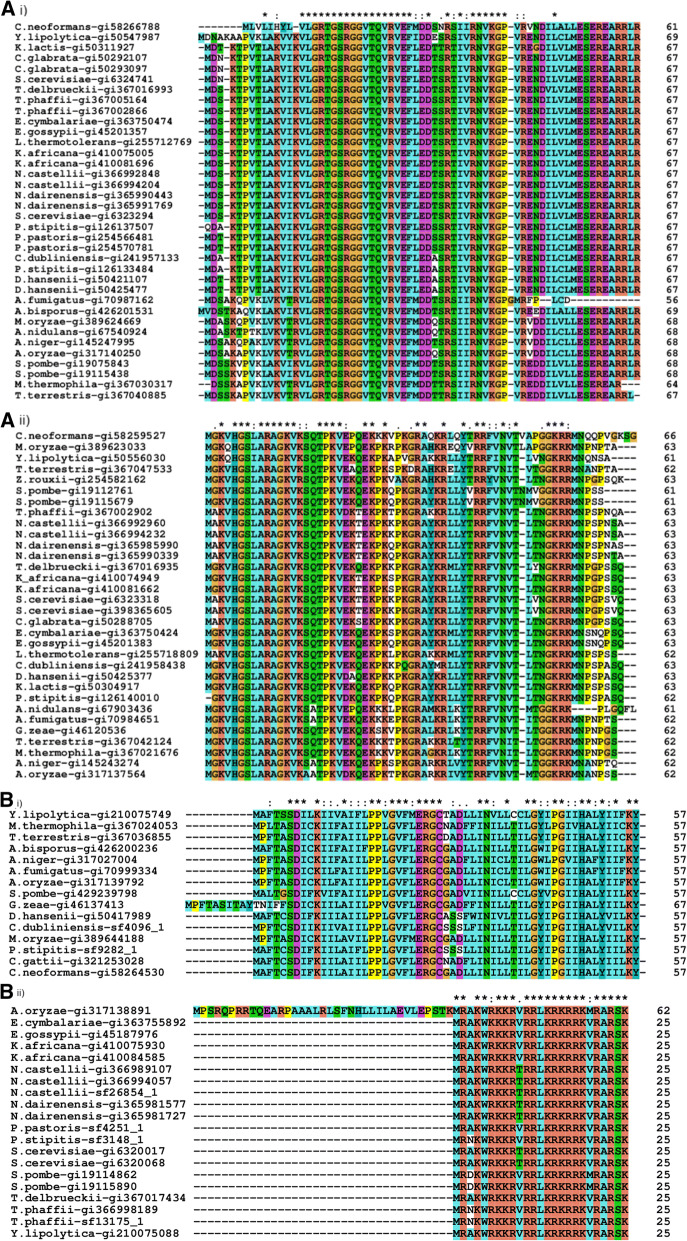

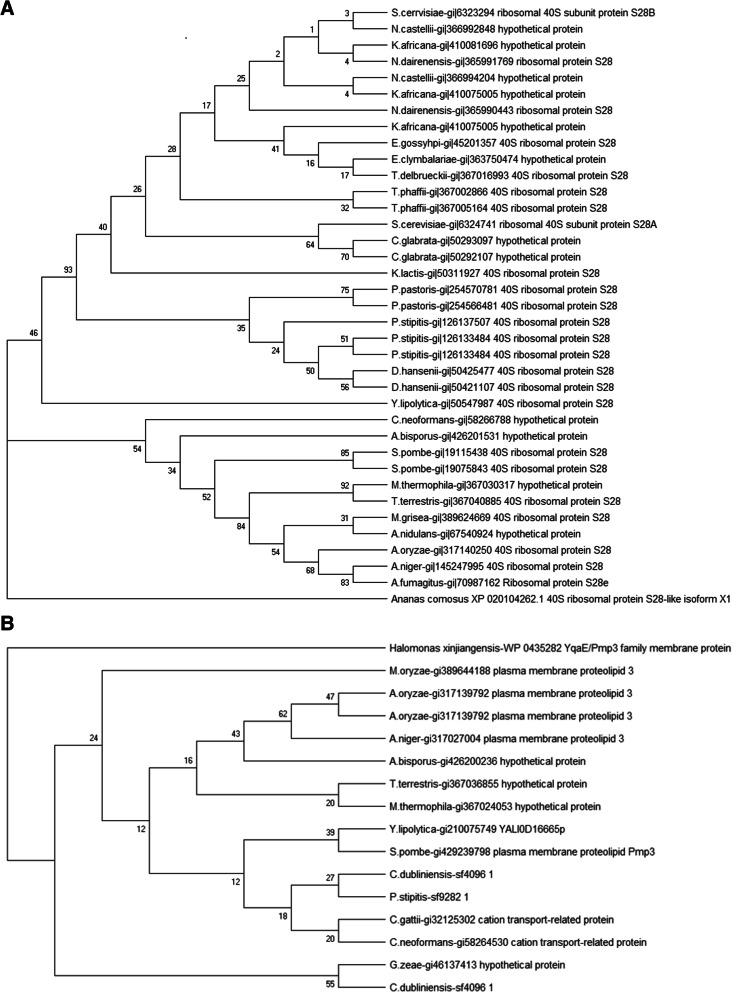

Although there were no predicted sORFs that were conserved in all 31 genomes, there were 68 sORFs from two homologous clusters that were present in 26 of the 31 fungal genomes. Additionally, there are 1663, 215, and 40 sORFs that could be found in ¼, ½ and ¾ of the 31 genomes, respectively (Fig. 4). The two clusters identified by the genome screening approach consist of sORFs that are homologous to 40S ribosomal protein S28 (Fig. 5a i) and 40S ribosomal protein S30 (Fig. 5a ii). In the first cluster, 11 sORFs from eight species, Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida glabrata, Eremothecium cymbalariae, Kazachstania africana, Naumovozyma castellii, Agaricus bisporus, Aspergillus nidulans and Myceliopthora thermophila that were originally annotated as hypothetical proteins, were updated to be homologs of 40S ribosomal protein S28. The annotation for this homology assignment was obtained using BLAST and domain analysis using InterProScan. Furthermore, the evolutionary analysis on this cluster showed that all of these sORFs are conserved in fungi and are closely related in the fungal group when compared against the outgroup, Ananas comosus (pineapple) (Fig. 6a). This demonstrates the utility of reannotation projects in general and especially when they are designed to identify specific targets such as the one we have carried out in updating the existing annotation.

Fig. 4.

Clustered conserved sORFs

Fig. 5.

Multiple sequence alignments for sORFs that are conserved within (a) 26 fungal genomes (i-xx3497 and ii-xx4629) and (b) 2/4 fungal genomes (i-xx4249 and ii-xx6165) based on clustering. The sORFs extracted from genome annotations have identifiers with ‘*gi*’ while those computed from this work have identifiers with ‘*sf*’

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetics of conserved sORFs within (a) 26 fungal genomes (xx3497) and (b) 2/4 fungal genomes (xx4249) based on clustering

The function of sORFs in the first alignment set, which are conserved in about half of the 31 genomes (Fig. 5b i), are proteolipid membrane potential modulators that modulate the membrane potential, particularly to resist high cellular cation concentration. In eukaryotic organisms, stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinases normally play crucial roles in transmitting environmental signals that will regulate gene expression for allowing the cell to adapt to cellular stress [30]. This protein is an evolutionarily conserved proteolipid in the plasma membrane which, in S. pombe, is transcriptionally regulated by the Spc1 stress MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinases) pathway. There are two sORFs (C. dubliniensis-sf4096_1 and P. pastoris-sf9282_1) from the computational reannotation that were clustered together with conserved alignments, and thus indicating they may have the same function (Table 2). Further evolutionary analysis of this cluster showed that all of the sORFs in this cluster are closely related in fungal group against bacteria, Halmonas xinjiangensis (Fig. 6b).

Table 2.

Characterization of sORFs conserved in 15 fungal genomes

| sORFs ID | Access Number | Existed Description | New Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| A.bisporus-gi426200236 | EKV50160.1 | hypothetical protein AGABI2DRAFT_115218 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| A.fumigatus-gi70999334 | XP_754386.1 | stress response RCI peptide | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| A.niger-gi317027004 | XP_001399936.2 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| A.oryzae-gi317139792 | XP_003189201.1 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| C.dubliniensis-sf4096_1 | NA | NA | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| C.gattii-gi321253028 | XP_003192603.1 | cation transport-related protein | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| C.neoformans-gi58264530 | XP_569421.1 | cation transport-related protein | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| D.hansenii-gi50417989 | XP_457739.1 | DEHA2C01320p | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| G.zeae-gi46137413 | XP_390398.1 | hypothetical protein FG10222.1 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| M.oryzae-gi389644188 | XP_003719726.1 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| M.thermophila-gi367024053 | XP_003661311.1 | hypothetical protein MYCTH_2314489 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| P.stipitis-sf9282_1 | NA | NA | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| S.pombe-gi429239798 | NP_595350.2 | plasma membrane proteolipid Pmp3 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| T.terrestris-gi367036855 | XP_003648808.1 | hypothetical protein THITE_2106674 | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

| Y.lipolytica-gi210075749 | XP_502906.2 | YALI0D16665p | plasma membrane proteolipid 3 |

The second alignment in Fig. 5b ii shows four sORFs predicted from the reannotation that are homologs to the 60S ribosomal protein. This is a possible indicator that sORFs may have been missed during a standard genome annotation process. Our analysis identified a higher number of sORFs candidates in S. cerevisiae compared to that published by Kastenmayer et al. [14]. The total of 77 sORFs predicted for S. cerevisiae contained all the 16 sORFs predicted by Kastenmayer et al. There are 20 sORFs in this set that were predicted by the sORFfinder and getorf integrated prediction process (Table 3). The other 57 sORFs predicted for S. cerevisiae have already been previously identified and was extracted from the genome screening approach.

Table 3.

List of sORFs predicted in S. cerevisiae

| from this study | Kastenmayer et al | from this study | Kastenmayer et al |

|---|---|---|---|

| S.cerevisiae-gi14318502 | YFL017W-A | S.cerevisiae-gi6323292 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398364355 | YFR032C-A | S.cerevisiae-gi6323318 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365385 | YNL024C-A | S.cerevisiae-gi6323506 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365605 | YLR287C-A | S.cerevisiae-gi6323558 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365775 | YOR210W | S.cerevisiae-gi6323634 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365789 | YDR139C | S.cerevisiae-gi6323912 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398366075 | YLR388W | S.cerevisiae-gi6324184 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6321622 | YGR183C | S.cerevisiae-gi6324259 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6321937 | YHR143W-A | S.cerevisiae-gi6324313 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6323294 | YLR264W | S.cerevisiae-gi6324619 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6323357 | YLR325C | S.cerevisiae-gi6324877 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6324070 | YNL259C | S.cerevisiae-gi6325391 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6324360 | YNR032C-A | S.cerevisiae-gi73858744 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6324741 | YOR167C | S.cerevisiae-gi7839147 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi7839181 | YHR072W-A | S.cerevisiae-sf1119_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi12621478 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf19568_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi147921768 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf21_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438768 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf21973_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438785 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf22173_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438820 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf23868_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438821 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf27242_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438834 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf27243_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438835 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf27714_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438838 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf3100_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi33438839 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf31758_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365465 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf32431_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398365709 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf32615_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398366109 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf34463_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398366483 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf35098_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398366543 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf4587_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi398366617 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf7880_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi41629681 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf85063_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6226526 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf85096_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6226533 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-sf9229_1 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6320017 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-gi6320482 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6320068 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-gi6320734 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6320142 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-gi6320819 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6320291 | #N/A | S.cerevisiae-gi6322272 | #N/A |

| S.cerevisiae-gi6323020 | #N/A |

In 274 clusters predicted from the 31 fungal genomes, 892 putative conserved sORFs have been annotated previously as a gene and have known functions. Characterization of the putative conserved sORFs revealed that approximately 3.8% of the newly predicted sORFs have known functions but were not annotated as genes in the available genome annotations. Our sORF annotation workflow also determined that 832 of the putative conserved sORFs predicted are hypothetical proteins or have no characterized function (Fig. 3). Even though these sORFs do not have a known function, their conservation across multiple species imply that their presence is of some functional importance. Out of the total of 848 predicted sORFs from the 31 genomes (Fig. 3), 93 sORFs from the sORFfinder-getorf integration output have homologs in other organisms (Additional file 2).

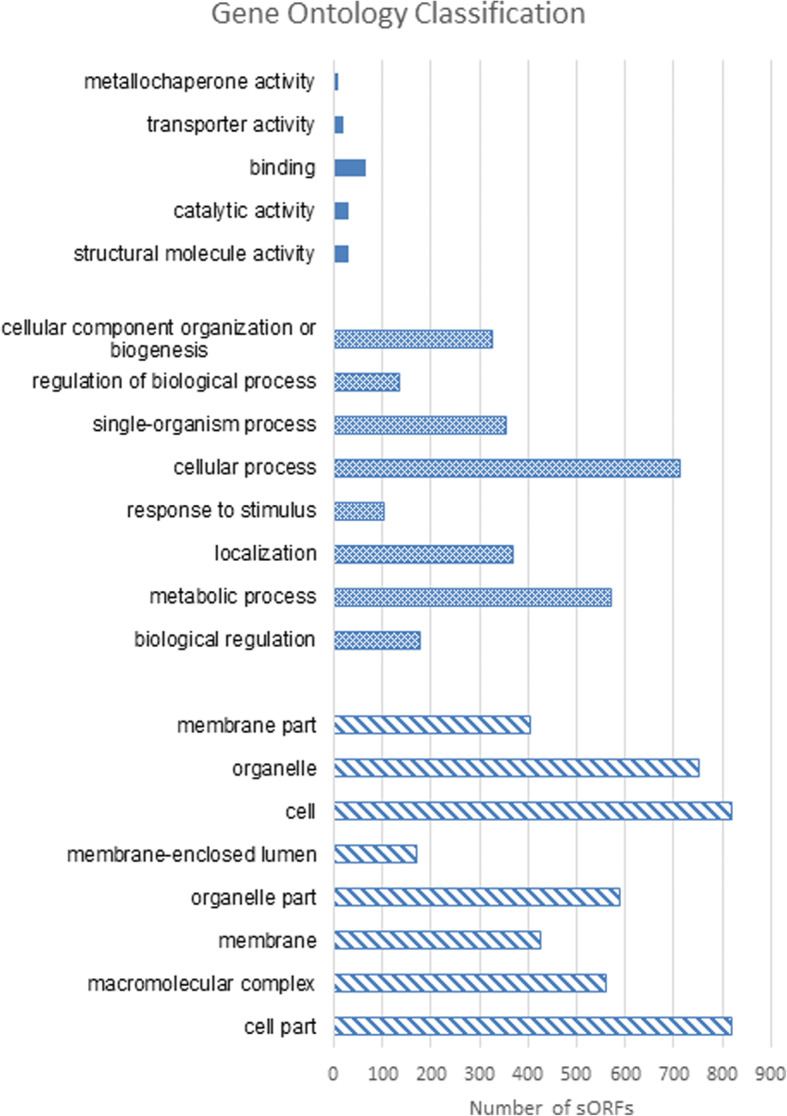

The total 1986 predicted sORFs were blast searched against the refseq database [31] and classified according to the three major Gene Ontology (GO) classes of molecular function, biological process and cellular component. Of the 1986 sORFs predicted, only 617 predicted sORFs could not be classified according to GO classes. This resulted in 2746 putative sORFs being classified into biological process, 4546 putative sORFs classified as cellular components and 155 predicted sORFs classified to be involved in molecular function (Fig. 7). The number of genes resulting from the Gene Ontology classification are higher than the total number of predicted sORFs predicted because one gene can be associated with multiple classes. The overall classification showed that most of the sORFs predicted have roles in biosynthesis and nucleic acid metabolism.

Fig. 7.

Classification of predicted conserved sORFs based on Gene Ontology. The solid colors represents cellular components, the dot patterns represents biological processes and cross patterns represents molecular functions

In the cellular component classification - there were 184 predicted sORFs classified into mitochondria (59), nucleus (57), endoplasmic reticulum (13), integral component of membrane (33) and Ssh1 translocon complex (22). Under the molecular function classification - the predicted sORFs were assigned to functions associated to mating pheromone activity (11), DNA and RNA binding (41), ribosome (145), cytochrome (7), protein binding (31), zinc ion binding (22), hydrogen ion transmembrane transporter activity (39), metal ion binding (16), protein heterodimerization activity (1), oxidoreductase activity (1), ATP binding (1), GTP binding (1) and ligase activity (1). For biological process GO classification, the 115 predicted sORFs in this group were classified into ribosome biogenesis (26), carbohydrate metabolic process (2), mitochondrial electron transport (4), DNA repair (1), mRNA export from nucleus (4), translation (10), protein N-linked glycosylation (1), protein targeting and targeting (3), copper ion transport (5), nucleocytoplasmic transport (14), response to stress (2), protein secretion (3), protein import into mitochondrial matrix (7), mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV assembly (14), regulation of catalytic activity (8), transmembrane transport (1), vacuolar proton-transporting V-type ATPase complex assembly (5) and mitochondrial outer membrane translocase complex assembly (1).

Based on the cellular component classification, the secreted sORFs are associated with roles in communication, differentiation and establishing clonal behaviour. The secreted sORFs predicted that was associated to mating pheromone activity were 34–35 amino acids in length. There are 51 predicted sORFs that were associated with functions as membrane features or even in modulating cell membrane thickness or fluidity to respond to changing environmental conditions. One such example is the predicted sORF encoding 52 residues that is associated with plasma membrane proteolipid 3 (Pmp3p), which is part of the phosphoinositide-regulated stress sensor that has a role in the modulation of plasma membrane potential and in the regulation of intracellular ion homeostasis [32].

The methods that we have developed from available and proven tools are expected to be easily deployable to other genomes as and when they become available with minimal modifications. Recently, a psychrophilic yeast genome had been reported [33] that has other functional data also available such as gene expression during cold stress [34, 35] and the characterization of proteins involved in cold adaptation [36–38]. The mining of such genomes for sORFs that can then be integrated to the functional data may be a cost-effective means of identifying sORFs that are involved in psychrophily or other relevant extremophilic adaptations.

Conclusions

The results of our work reveal that a high number of potential sORFs could be overlooked by the standard gene prediction workflow. We therefore recommend that the standard genome annotation process be complemented by analyses that specifically target the annotation of sORFs [39, 40], and then have both results integrated to provide a more complete genome annotation. This workflow is applicable for big data analysis because this study involved a large number of sequences from 31 completed fungal genomes that consisted of intergenics, introns, ORFs and genome sequences. Although the functional validation for predicted sORFs cannot be done based solely on the genome sequence without any corresponding transcriptomic or proteomic data, it is still possible to imply a putative status for the predicted sORFs by evaluating their conservation with the assumption, albeit a very simplistic one, that the observed conservation implies a conserved function of some biological importance and thus less likely to be artefacts of the gene prediction process. Furthermore, the predicted sORFs predicted will be incorporated into a database consisting of sORFs from fungal genomes.

Methods

A workflow was created to predict sORFs from fungal genomes (Fig. 1) and the components and steps involved are provided below. The source code for the programs in this workflow have been deposited on GitHub - https://github.com/firdausraih/sORFs-fungal-genomes (Additional file 3). The data for sORFs were sourced from two datasets: (i) existing annotations made available with the genome sequences and (ii) a purpose built search.

Source of genome data

The data for 31 fungi genomes were downloaded via FTP from the NCBI at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/archive/old_refseq/Fungi/ (Table 1). These 31 fungi genomes were selected from 36 fungi genomes in NCBI based on the completeness of their genome analysis and annotation.

Screening sORFs from genome annotation

Known or existing sORF annotations were first extracted from the existing genome annotations available for the fungal genomes used. This dataset was restricted to annotations for a maximum length of less than 240 nucleotides or 80 amino acids.

Identification of intergenic, intronic and coding regions

The intronic and coding regions for the genomes were identified using Artemis [41] [https://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/tools/artemis] based on the chromosome, scaffold or contig sequences and the protein coding sequences for each genome. The intergenic regions were extracted from the genome annotations in the General Feature Format (GFF) format using a Perl script. The intergenic regions were extracted from both the forward and reverse strands.

Identification of sORF using sORFfinder-getorf approaches

Gene predictions that specifically targeted the identification of sORFs were done by using sORFfinder-getorf approaches that combined two programs: getorf and sORFfinder. The prediction of the sORFs were carried out for each scaffold and/or chromosome. The sORFs predictions using getorf from the EMBOSS package [23, 42] were restricted to a maximum length of 240 nucleotides. Identification of sORFs by sORFfinder [24] was carried out using a 0.5 probability parameter. The results of sORFfinder, which by default is set at a maximum of 100 amino acids, were then filtered for output containing 80 amino acids in length.

Determining existing homologs for the predicted sORFs

The predicted sORFs from getorf and sORFfinder search outputs for each fungi genome were combined and clustered using CD-HIT-EST [25, 43] and those with 100% identify were removed. Unique sequences that represented each cluster were then used as BLAST queries to search against a database of open reading frames (ORFs) for 31 fungal genomes using BLASTX [44, 45]. BLAST hits that aligned to less than two thirds of the query sequences and with less than 30% sequence identity were removed and the remainder were used as a potential sORFs dataset.

Identification of conserved sORFs

The pre-annotated sORFs and those that were predicted as potential sORFs were then combined and clustered using CD-HIT at 70% identity to remove clusters that contained only a single sequence. For each cluster, sORFs that have homologs in at least two different species in one cluster were considered as potentially conserved sORFs. All conserved sORFs were identified their Kozak sequences using CPC2 [26].

Multiple sequence alignments and evolutionary analysis

Identification of conserved sORFs in the clusters were carried out using the MUSCLE [46] sequence alignment program. A multiple sequence alignment generated using MUSCLE, which included one out group identified by PSI-BLAST [45], was used as input to construct a phylogenetic tree with 1000 bootstrap replications using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model based on the Neighbor joining method using PHYLIP 3.695 [47, 48].

Function prediction and classification

The predicted sORFs were annotated using blast, interpro and classified using BLAST2GO into the three main Gene Ontology classes of molecular function, biological processes and cellular component [49–51].

Additional files

A listing of 1986 putative conserved sORFs predicted. This file contains a list of 1986 putative conserved sORFs predicted from all fungal genomes that can be viewed using Microsoft excel or text viewer. (TXT 151 kb)

List of predicted sORFs with homologs. This file contains a list of sORFs predicted from all fungal genomes with their homologs that can be viewed using Microsoft excel or a text viewer. (TXT 118 kb)

Pseudocode for sORFs workflow. This file contains a pseudocode for finding sORFs workflow using Linux environment using BASH, PYTHON and the Perl programming language. (ZIP 8 kb)

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the use of computational resources at the Malaysia Genome Institute, and computing facilities at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Funding

These investigations were supported by the grants 02–05-20-SF0007/3 from the Ministry of Science, Technology & Innovation (MOSTI) and DIP-2017-013 from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia as well as a MyPHD scholarship and attachment funding via LEP 2.0/14/UKM/BT/02/2 from the Ministry of Education Malaysia to SMS. Publication costs are funded by Centre for Research Instrumentation and Management (CRIM) and the Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the NCBI at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/archive/old_refseq/Fungi/ and all sORFs identified in this study are in the Additional file 2 provided.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Bioinformatics, Volume 19 Supplement 13, 2018: 17th International Conference on Bioinformatics (InCoB 2018): bioinformatics. The full contents of the supplement are available at https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-13.

Abbreviations

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CD-HIT

Cluster Database at High Identity with Tolerance

- EMBOSS

The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite

- FTP

File Transfer Protocol is a standard network protocol used for the transfer data

- MUSCLE

MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ORFs

Open Reading Frames

- PHYLIP

PHYLogeny Inference Package

- PSI-BLAST

Position-Specific Iterated BLAST

- sORFs

small Open Reading Frames

Authors’ contributions

MFR conceived the project. SMS carried out the analysis. MFR and SMS wrote the paper. MFR and SMS approved of the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shuhaila Mat-Sharani, Email: shuhaila@mfrlab.org.

Mohd Firdaus-Raih, Email: firdaus@mfrlab.org.

References

- 1.Andrews SJ, Rothnagel JA. Emerging evidence for functional peptides encoded by short open reading frames. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(3):193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrg3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dujon B, Alexandraki D, André B, Ansorge W, Baladron V, Ballesta JPG, Banrevi A, Bolle PA, Bolotin-Fukuhara M, Bossier P, et al. Complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome XI. Nature. 1994;369:371. doi: 10.1038/369371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274(5287):546. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkholder WF, Kurtser I, Grossman AD. Replication initiation proteins regulate a developmental checkpoint in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2001;104(2):269–279. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita M, Losick R. Evidence that entry into sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is governed by a gradual increase in the level and activity of the master regulator Spo0A. Genes Dev. 2005;19(18):2236–2244. doi: 10.1101/gad.1335705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pueyo JI, Couso JP. The 11-aminoacid long tarsal-less peptides trigger a cell signal in Drosophila leg development. Dev Biol. 2008;324(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galindo MI, Pueyo JI, Fouix S, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Peptides encoded by short ORFs control development and define a new eukaryotic gene family. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(5):e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleason CA, Liu QL, Williamson VM. Silencing a candidate nematode effector gene corresponding to the tomato resistance gene mi-1 leads to acquisition of virulence. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008;21(5):576–585. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-5-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee C, Wan J, Miyazaki B, Fang Y, Guevara-Aguirre J, Yen K, Longo V, Bartke A, Cohen P. IGF-I regulates the age-dependent signaling peptide humanin. Aging Cell. 2014;13(5):958–961. doi: 10.1111/acel.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Yen K, Cohen P. Humanin: a harbinger of mitochondrial-derived peptides? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24(5):222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law GL, Raney A, Heusner C, Morris DR. Polyamine regulation of ribosome pausing at the upstream open reading frame of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(41):38036–38043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basrai MA, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Small open reading frames: beautiful needles in the haystack. Genome Res. 1997;7(8):768–771. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.8.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemm MR, Paul BJ, Schneider TD, Storz G, Rudd KE. Small membrane proteins found by comparative genomics and ribosome binding site models. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70(6):1487–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kastenmayer JP, Ni L, Chu A, Kitchen LE, Au W-C, Yang H, Carter CD, Wheeler D, Davis RW, Boeke JD, et al. Functional genomics of genes with small open reading frames (sORFs) in S. cerevisia. Genome Res. 2006;16(3):365–373. doi: 10.1101/gr.4355406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanada K, Higuchi-Takeuchi M, Okamoto M, Yoshizumi T, Shimizu M, Nakaminami K, Nishi R, Ohashi C, Iida K, Tanaka M, et al. Small open reading frames associated with morphogenesis are hidden in plant genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(6):2395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213958110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn J, Tsoy OV, Thalmann S, Čuklina J, Gelfand MS, Evguenieva-Hackenberg E. Small open Reading frames, non-coding RNAs and repetitive elements in Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladoukakis E, Pereira V, Magny E, Eyre-Walker A, Couso JP. Hundreds of putatively functional small open reading frames in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2011;12(11):R118. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frith MC, Forrest AR, Nourbakhsh E, Pang KC, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Bailey TL, Grimmond SM. The abundance of short proteins in the mammalian proteome. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(4):e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slavoff SA, Mitchell AJ, Schwaid AG, Cabili MN, Ma J, Levin JZ, Karger AD, Budnik BA, Rinn JL, Saghatelian A. Peptidomic discovery of short open reading frame–encoded peptides in human cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;9:59. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erpf PE, Fraser JA. The long history of the diverse roles of short ORFs: sPEPs in Fungi. Proteomics. 2018;18(10):1700219. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201700219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sopko R, Andrews B. Small open reading frames: not so small anymore. Genome Res. 2006;16(3):314–315. doi: 10.1101/gr.4976706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson SA. EMBOSS opens up sequence analysis. European molecular biology open software suite. Brief Bioinform. 2002;3(1):87–91. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanada K, Akiyama K, Sakurai T, Toyoda T, Shinozaki K, Shiu S-H. sORF finder: a program package to identify small open reading frames with high coding potential. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(3):399–400. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang YJ, Yang DC, Kong L, Hou M, Meng YQ, Wei L, Gao G. CPC2: a fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W12–W16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Li S, Zhang Y, Zheng H, Xu Z, Ye J, Yu J, Wong GK. Vertebrate gene predictions and the problem of large genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4(9):741–749. doi: 10.1038/nrg1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanada K, Zhang X, Borevitz JO, Li W-H, Shiu S-H. A large number of novel coding small open reading frames in the intergenic regions of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome are transcribed and/or under purifying selection. Genome Res. 2007;17(5):632–640. doi: 10.1101/gr.5836207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyberg KG, Machado CA. Comparative expression dynamics of intergenic long noncoding RNAs in the genus Drosophila. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(6):1839–1858. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudd KE, Humphery-Smith I, Wasinger VC, Bairoch A. Low molecular weight proteins: a challenge for post-genomic research. Electrophoresis. 1998;19(4):536–544. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Block J, Szopinska A, Guerriat B, Dodzian J, Villers J, Hochstenbach J-F, Morsomme P. Yeast Pmp3p has an important role in plasma membrane organization. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(19):3646–3659. doi: 10.1242/jcs.173211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Firdaus-Raih M, Hashim NHF, Bharudin I, Abu Bakar MF, Huang KK, Alias H, Lee BKB, Mat Isa MN, Mat-Sharani S, Sulaiman S, et al. The Glaciozyma Antarctica genome reveals an array of systems that provide sustained responses towards temperature variations in a persistently cold habitat. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh JSP, Wong CMVL, Najimudin N, Mahadi NM. Gene expression patterns of Glaciozyma antarctica PI12 in response to cold- and freeze-stresses. Polar Science. 2018;1-39. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1873965218301464. (in press)

- 35.Bharudin I, Zolkefli R, Bakar MFA, Kamaruddin S, Illias RM, Najimudin N, Mahadi NM, Bakar FDA, Murad AMA. Identification and expression profiles of amino acid biosynthesis genes from psychrophilic yeast, Glaciozyma antarctica. Sains Malaysiana. 2018;47(8):1675–1684. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2018-4708-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashim NH, Bharudin I, Nguong DL, Higa S, Bakar FD, Nathan S, Rabu A, Kawahara H, Illias RM, Najimudin N, et al. Characterization of Afp1, an antifreeze protein from the psychrophilic yeast Glaciozyma antarctica PI12. Extremophiles. 2013;17(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s00792-012-0494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashim NHF, Sulaiman S, Bakar FDA, Illias RM, Kawahara H, Najimudin N, Mahadi NM, Murad AMA. Molecular cloning, expression and characterisation of Afp4, an antifreeze protein from Glaciozyma antarctica. Polar Biol. 2014;37(10):1495–1505. doi: 10.1007/s00300-014-1539-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusof NA, Hashim NH, Beddoe T, Mahadi NM, Illias RM, Bakar FD, Murad AM. Thermotolerance and molecular chaperone function of an SGT1-like protein from the psychrophilic yeast, Glaciozyma antarctica. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21(4):707–715. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0696-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohd-Padil H, Damiri N, Sulaiman S, Chai S-F, Nathan S, Firdaus-Raih M. Identification of sRNA mediated responses to nutrient depletion in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17356-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoo J-S, Chai S-F, Mohamed R, Nathan S, Firdaus-Raih M. Computational discovery and RT-PCR validation of novel Burkholderia conserved and Burkholderia pseudomallei unique sRNAs. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(Suppl 7):S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S7-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream M-A, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(10):944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullan LJ, Bleasby AJ. Short EMBOSS user guide. European molecular biology open software suite. Brief Bioinform. 2002;3(1):92–94. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Y, Niu B, Gao Y, Fu L, Li W. CD-HIT suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):680–682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(2):20–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altschul S, Madden T, Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D, Gapped BLAST. PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdennadher N, Boesch R. Porting PHYLIP phylogenetic package on the desktop GRID platform XtremWeb-CH. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;126:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package) version 3.6. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conesa A, Gotz S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int J Plant Genomics. 2008;2008:619–832. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, Robles M, Talon M, Dopazo J, Conesa A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(10):3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aparicio G, Gotz S, Conesa A, Segrelles D, Blanquer I, Garcia JM, Hernandez V, Robles M, Talon M. Blast2GO goes grid: developing a grid-enabled prototype for functional genomics analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;120:194–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A listing of 1986 putative conserved sORFs predicted. This file contains a list of 1986 putative conserved sORFs predicted from all fungal genomes that can be viewed using Microsoft excel or text viewer. (TXT 151 kb)

List of predicted sORFs with homologs. This file contains a list of sORFs predicted from all fungal genomes with their homologs that can be viewed using Microsoft excel or a text viewer. (TXT 118 kb)

Pseudocode for sORFs workflow. This file contains a pseudocode for finding sORFs workflow using Linux environment using BASH, PYTHON and the Perl programming language. (ZIP 8 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the NCBI at ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/archive/old_refseq/Fungi/ and all sORFs identified in this study are in the Additional file 2 provided.