Abstract

Introduction

Living with and beyond a diagnosis of a low- and intermediate-grade glioma (LIGG) can adversely impact many aspects of people’s lives and their quality of life (QoL). In people with chronic conditions, self-management can improve QoL. This is especially true if people are supported to self-manage. Supported self-management programmes have been developed for several cancers, but the unique challenges experienced by LIGG survivors mean these programmes may not be readily transferable to this group. The Ways Ahead study aims to address this gap by exploring the needs of LIGG survivors to develop a prototype for a supported self-management programme tailored to this group.

Methods and analysis

Ways Ahead will follow three sequential phases, underpinned by a systematic review of self-management interventions in cancer. In phase 1, qualitative methods will be used to explore and understand the issues faced by LIGG survivors, as well as the barriers and facilitators to self-management. Three sets of interviews will be conducted with LIGG survivors, their informal carers and professionals. Thematic analysis will be conducted with reference to the Theoretical Domains Framework and Normalisation Process Theory. Phase 2 will involve co-production workshops to generate ideas for the design of a supported self-management programme. Workshop outputs will be translated into a design specification for a prototype programme. Finally, phase 3 will involve a health economic assessment to examine the feasibility and benefits of incorporating the proposed programme into the current survivorship care pathway. This prototype will then be ready for testing in a subsequent trial.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been reviewed and approved by an National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (REC ref: 20/WA/0118). The findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations, broadcast media, the study website, The Brain Tumour Charity and stakeholder engagement activities.

Keywords: health economics, neurological oncology, adult oncology, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Ways Ahead will develop an evidence-based and theoretically-informed supported self-management programme specifically designed to improve quality of life in adult primary brain tumour survivors.

The methodological approach benefits from the use of recognised frameworks for systematic intervention development, and the incorporation of key stakeholder perspectives through all stages of intervention development, to optimise programme relevance, acceptability, usability and feasibility.

The inclusion of an economic assessment at the development stages affords the opportunity to consider how the programme might integrate with existing pathways and to optimise its efficiency.

The outcome of the study will be a prototype programme ready to be taken forward for testing. In the meantime, dissemination of findings may stimulate survivors to initiate new self-management strategies and encourage clinical teams to place greater emphasis on supporting self-management in brain tumour follow-up.

While the findings will be specifically applicable to those with low- and intermediate-grade gliomas, some may be generalisable to other groups with brain tumours.

Introduction

Each year in the UK, more than 10 000 new primary brain tumours are diagnosed. Over the past 40 years, survival has doubled; 5-year survival is now 60% for those aged 15 to 39 years at diagnosis and 35% for those aged 40 to 49 years. These trends mean that there is a growing population of people, in particular younger adults, living with and beyond a primary brain tumour diagnosis.1

A brain tumour can have a devastating impact on an individual’s life, and many of the problems and needs are specific to this form of cancer. Patients can experience a range of common cancer-related symptoms (e.g. fatigue, sleep disorders and pain) as well as others specifically related to the tumour and its treatment (e.g. cognitive limitations, seizures, visual impairment, changes in personality and behaviour, speech problems and mobility problems).2–4 These symptoms can occur in clusters and get worse as the disease progresses.5–7 Cognitive deficits, in particular, increase as the disease progresses, hampering communication and decision-making.6 This can contribute to changing social roles, loss of independence and isolation.4 Patients often experience significant distress, depression and anger.8–10 These, in turn, adversely impact physical and psychosocial quality of life (QoL).11 12

As a result of the tumour, its treatment and treatment side-effects, those living with a brain tumour often have multi-faceted and complex supportive care needs. However, these needs often go unmet, in part due to poor communication with, and information from, healthcare providers, as well as low referral to and use of psychosocial services.6 13 14 Given this burden, it is essential to identify effective ways to empower and support adults living with a primary brain tumour to manage the specific problems that they face, adjust to life after treatment, and optimise their well-being and QoL.

Self-management is an ‘individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition’.15 There is a large and growing evidence base indicating that self-management programmes can improve various clinical and psychosocial outcomes—including QoL, psychological well-being and healthcare utilisation—in people with long-term conditions.16 However, to successfully self-manage, patients need a set of skills (such as problem solving, action planning/goal setting and communicating with healthcare providers) as well as the motivation and confidence to manage their condition. Self-management interventions seek to equip people with these skills and confidence, usually by improving self-efficacy.17

Self-management is not—and should not be—the sole responsibility of the patient.18 They need support from a network of health professionals, family and friends, and fellow patients.19 Thus, self-management programmes must consider what health professionals and health services can do to support people to self-manage, and how best to mobilise social resources.20 Indeed, self-management strategies co-created with patients and providers are more likely to have positive effects.16

There is emerging evidence that both problem-focussed and adjustment-focussed programmes can improve cancer survivors’ self-efficacy, social, physical and psychological well-being, and QoL.21–26 However, the potential for self-management in adults living with a primary brain tumour has not been well investigated. The unique and complex needs of this group means that programmes developed for other conditions or cancers are unlikely to be suitable or easily transferable.

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim of the Ways Ahead study is to design an evidence-based and theoretically-informed supported self-management programme to improve QoL in adults living with a specific form of brain tumour—low- and intermediate-grade glioma (LIGG).

Objectives

The objectives of the Ways Ahead study are to:

Identify the characteristics and components of successful self-management interventions that have been tested in adult cancer survivors.

Identify self-management strategies currently used by people living with LIGGs.

Explore individual-level barriers to, and enablers of, self-management by people living with LIGGs.

Identify health system/service-level factors that would help or hinder implementation of a supported self-management programme for people living with LIGGs.

Co-produce a prototype for a supported self-management programme with survivors, informal carers and professionals.

Estimate the potential costs and benefits of implementing a supported self-management programme for LIGG survivors, and assess how this programme would change the current survivorship care pathway.

Methods and analysis

Overview of study design

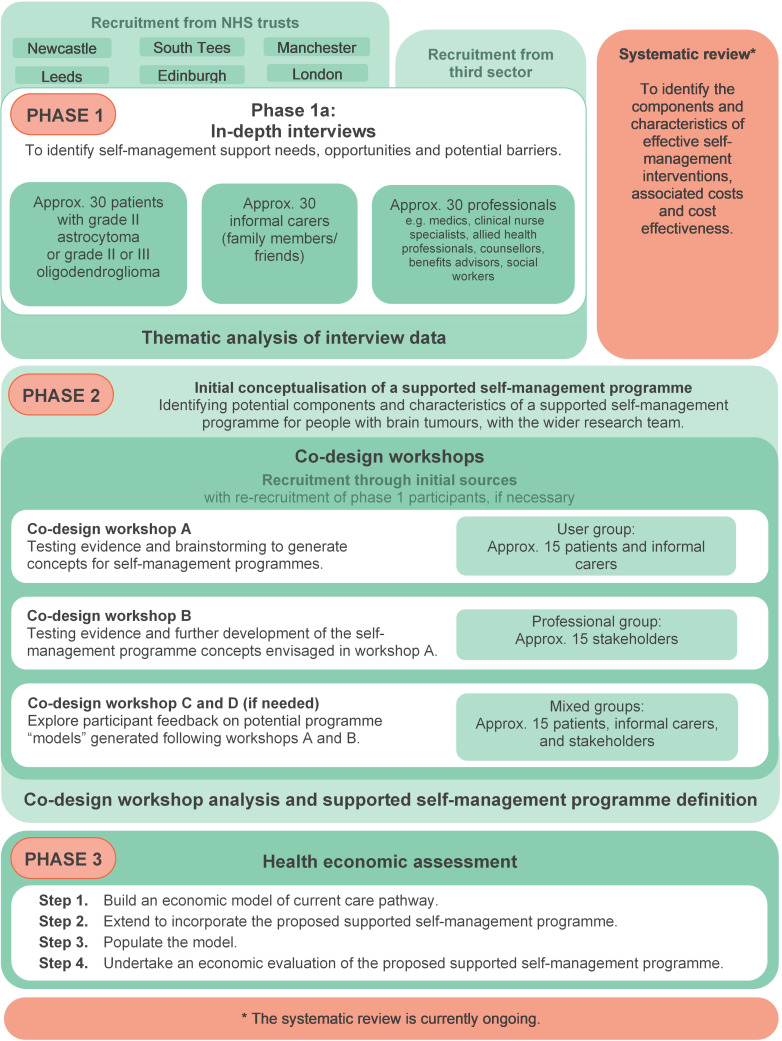

Ways Ahead is a 3-year multi-method study (2019 to 2022), involving three sequential phases, underpinned by a systematic review (figure 1). We are following established frameworks for the systematic development of interventions.27 28 In the first phase, three sets of semi-structured interviews will be conducted with patients, informal carers and professionals. These will identify barriers to, and enablers of, self-management, as well as self-management strategies currently used by people with LIGGs. The second phase will include co-production activities (namely workshops), in accordance with the sequential and systematic co-design approach of O’Brien et al.29 These workshops will integrate evidence, expert knowledge and experience, and stakeholder involvement to develop a prototype for a supported self-management programme. For the third phase, an economic model of current care pathways will be developed and extended to incorporate the proposed supported self-management programme, to assess its acceptability and feasibility. These three phases will be underpinned by an updated systematic review of components and characteristics of supported self-management interventions which have been tested among adults living with cancer.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the phases of the Ways Ahead study.

Table 1 summarises how the activities for each interview set and co-design workshop will be tailored to the different samples involved in this study.

Table 1.

Summary of data collection activities for phases 1 and 2

| Phase (component) | Description |

| P1 (patients) | The survivor topic guide will cover: the impact of the brain tumour on health and well-being; understanding and views of self-management; self-management strategies currently and previously used by the individual; other self-management strategies the individual might like to, or be willing to use; experience of formal and informal support for self-management; difficulties experienced with, and barriers to, self-management; and what would help the individual better self-manage. |

| P1 (informal carers) | The informal carer topic guide will cover: their views and attitudes towards self-management for their support recipient; their contributions to support the recipient’s self-management; and barriers and facilitators to support the recipient self-managing. |

| P1 (professionals) | The professionals’ topic guide will cover: views on main areas of unmet needs among LIGG survivors; potential for self-management among LIGG survivors; own experiences of patients who have used self-management; and what would be needed to successfully deliver supported self-management for LIGG survivors. |

| P2 (workshop A) | Workshop A with survivors and informal carers will generate ideas for what is needed to improve self-management in LIGG survivors and what support would be useful. Potential activities include presenting evidence statements based on the systematic review and phase 1, asking participants to review and prioritise these. To generate intervention design ideas, personas66 (‘characters’ representing different people affected by LIGG) will be generated prior to the workshop. Workshop participants will be asked to consider what an intervention for each specific persona might involve (components, mode of delivery and so on). De Bono’s ‘Six hats’ approach67 may also be used to encourage participants to reflect on the needs and perspectives of patients, informal carers and professionals. |

| P2 (workshop B) | Workshop B with professionals and other stakeholders will follow a similar format to workshop A, and develop the ideas generated by survivors and informal carers. Participants will also discuss the feasibility of implementing the concepts from workshop A into current care pathways. |

| P2 (workshop C and D) | Workshop C and, if needed, D, with survivors, informal carers, professionals and stakeholders will seek participant feedback on supported self-management programme prototypes, developed following workshops A and B. Participants will discuss potential challenges around acceptability and feasibility of survivors’ effectively engaging with the programme. |

LIGG, low- and intermediate-grade glioma.

Systematic review

The review, which has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019154115), will follow PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.30

MEDLINE/Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Scopus will be searched for papers published in English, which evaluate: an intervention which is described as self-management or as seeking to develop self-management skills; targeted at adults diagnosed with cancer; during the survivorship phase (i.e. after completion of primary treatment and not at end-of-life); studies using design with a comparator (eg, controlled trials, feasibility or pilot studies with control groups, and pre–post design) will be eligible.

Abstracts and titles will be sifted independently by two team members. Full texts of articles deemed potentially eligible will be obtained and reviewed by two team members. Reference lists of eligible articles and relevant reviews will be searched to identify any articles missed. Eligible studies will be assessed for risk of bias using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for randomised studies,31 and the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for non-randomised studies.32 The TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) checklist will be used to describe the characteristics of the interventions; that is, systematically describe each intervention in terms of (i) mode of delivery (e.g. face-to-face or web-based); (ii) personnel delivering the support (e.g. healthcare professionals or lay educators); (iii) targeting (e.g. individually tailored or group-based); and (iv) intervention intensity, frequency and duration.33 The PRISMS (Practical Reviews in Self-Management Support) taxonomy18 will be used to abstract the self-management components of the interventions (e.g. information about condition/management, provision of equipment and social support). Data will be abstracted on health-related QoL (HRQoL), self-efficacy, as well as any other primary outcomes and any health economic outcomes. Narrative synthesis of eligible studies will be undertaken together with—if appropriate—meta-analysis, undertaken in RevMan, to identify which components or characteristics of the interventions are associated with improved HRQoL and self-efficacy.

Target population

The Ways Ahead study will focus on LIGGs, which are most commonly diagnosed in young adults in their 30s and 40s.34–37 In almost all cases, LIGGs will progress to high-grade gliomas or recur: they are rarely cured.38 Consequently, life expectancy following diagnosis with a LIGG is limited to around 5 to 15 years, depending on the subtype.36 37 39 Living for extended periods with a terminal condition can affect people’s ability to recuperate, cope with and resume everyday activities such as returning to work.40 Therefore, the development of a supported self-management programme is likely to be particularly beneficial for this patient group, but to achieve this, their distinct experiences and needs must be understood.

Setting and eligibility criteria

Ways Ahead will be conducted in partnership with several National Health Service (NHS) trusts, including Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and NHS Lothian. The study will also collaborate closely with The Brain Tumour Charity.

Table 2 summarises the inclusion criteria for participants in each interview set.

Table 2.

Summary of eligibility criteria for each participant group

| Group | Eligibility criteria |

| Patients |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Exclude if they: | |

| |

| |

| |

| Informal carers |

|

| |

| Professionals |

|

| |

| |

|

LIGG, low- and intermediate-grade glioma; NHS, National Health Service.

In accordance with Dworkin’s sample size policy,41 each interview set will likely require 25 to 30 participants for reasonable saturation, though this cannot be entirely pre-determined ahead of analysis.42 Purposive sampling strata will be defined for each interview set to ensure sample heterogeneity and elicitation of a broad range of views and experiences. The sampling strata for survivors and informal carers will be: time since diagnosis; treatment modality(ies); and gender. The sampling strata for professionals will be the clinical centre and discipline. We will also seek a maximum diversity sample of other professionals, in terms of organisation and role.

For phase 2, we will seek diversity among co-production workshop participants.

Recruitment procedures

Recruitment of survivors: phase 1

Identification and recruitment of survivors will happen in collaboration with healthcare professionals within the collaborating sites. Depending on site preference, two processes may be used.

Recruitment process 1: Potentially eligible survivors will be identified from their medical records and provided with an information sheet and reply slip, either face-to-face at a clinic visit, or by post. If the individual would like to take part or find out more information, they can return the reply slip to a member of clinic staff or post it to the study coordinator, and give permission for their contact details to be passed onto the study team or contact the study coordinator directly.

Recruitment process 2: Survivors may also be recruited via follow-up clinics. Information packs will be sent out, as above. Survivors will be informed that, at their next clinic visit, the researcher will be present and with their permission, will tell them more about the study and answer any questions. During the clinic conversation, the individual will be asked if they would be happy to take part and, if so, the interview will be scheduled. If they require more time to consider, the co-ordinator will telephone them in a few days for a final decision.

Recruitment of informal carers: phase 1

Survivors who have been interviewed will be asked to nominate someone who has been involved in helping care for/support them since diagnosis. The study team will provide the survivor with a carer study pack and ask them to pass it on to the carer. Informal carers may also be identified through collaborating sites, as healthcare professional sometimes know carers from their attendance to support a patient at a clinic visit.

Other recruitment routes for survivors and carers

If required, we will also use other routes to recruit patients and informal carers, including advertising through The Brain Tumour Charity’s Research Involvement Network (RIN) and on the Ways Ahead study website. We may also post on relevant online forums and social media platforms.

Recruitment of professionals: phase 1

Healthcare professionals who are members of the brain cancer multidisciplinary teams at collaborating sites will be invited to interview. Those interested will be asked to call, email or return a reply slip using a prepaid envelope to the study team. We will also promote the study through The Brain Tumour Charity healthcare professional network and invite potentially interested healthcare professionals to contact the study coordinator by email or telephone.

Cancer support professionals will be identified through patient support organisations or charities (i.e. Maggie’s Centre Newcastle, Brain Tumour Support, and The Brain Tumour Charity). We will write inviting them to be interviewed, with an information sheet attached. We will also allow for snowball sampling among this group.

Recruitment to phase 2

Recruitment for phase 2 co-production workshops will follow the same routes as phase 1. Participants from phase 1 will be invited to register their interest in taking part in phase 2, but we will also seek to include some survivors, informal carers and professionals who did not take part in phase 1.

Procedures

Table 1 provides a summary of the topics covered in each interview set, as well as the content of each workshop.

Phase 1: semi-structured interviews

Interviews will be conducted by research staff and take place either by phone, video call or face-to-face. Interviews will occur at a time and place convenient for the interviewee. Where possible, survivors and their informal carers will be interviewed separately so that each can be fully open and honest. Each interview is expected to last 60 to 90 minutes, or as long as the participant wishes. Once consent has been obtained, each participant will complete an ‘About you’ form, to collect some key demographic details such as age, education and employment status. The demographic questions asked vary appropriately for the survivors, informal carers and professionals.

Interviews will be informed by topic guides, which will be used flexibly to allow interviewees to raise issues they consider important. The interviewer will ask ‘headline’ open-ended questions for each area of interest on the topic guide; probes will then be used to explore issues in more depth. The topic guide may evolve as the interviews progress to examine emerging themes.

Phase 2: co-production workshops

Each workshop will take place in a neutral location and will be facilitated by members of the study team. It is expected that each workshop will last approximately 3 hours. Care will be taken to make sure participants understand that discussions taking place within the workshop are confidential. The researchers will ensure an atmosphere which is welcoming and non-judgemental, and it will be clear that all participants are treated as equals. Several activities will be used at each workshop (table 1) to engage participants, ensure workshops are interactive and interesting, and to facilitate discussion and interaction among participants.

Planned analysis

Analysis of the phase 1 interviews will occur in parallel with data collection to ensure that any new issues raised are explored in subsequent interviews. The first few interviews in each set will be independently coded by two team members, who will discuss and arrange the emerging codes and themes to be applied to the remainder of the interview set. Each interview set will be analysed separately using both inductive and deductive approaches. For inductive analysis, thematic analysis, within the framework approach, will be used.43–45 For the more deductive phases, self-management strategies used by survivors and informal carers will be identified and classified following Yun et al46 and Dunne et al.47 The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)48 will also be used to identify which domains influence the self-management behaviours of people with LIGG.

Normalisation Process Theory (NPT)49 will be used to aid the analysis of professional interviews. This will identify key service/system issues, which might help or hinder implementation of a supported self-management programme. For analytical rigour, the classification of self-management strategies, belief statements to the TDF domains, and NPT constructs will be discussed and agreed within the team.

Findings from the interviews and the systematic review will be combined into a ‘theoretical model’ of supported self-management in LIGGs. This will identify which influences on self-management are potentially modifiable to determine what needs to be done to change survivors’ self-management behaviours. The behaviour change wheel (BCW)50 will be used to map the TDF domains within the theoretical model onto intervention functions that might be effective in changing self-management behaviours. Associated behaviour change techniques (BCT) will be identified from the BCT taxonomy,51 that is, the techniques that can be used to overcome barriers to, and enhance enablers of, self-management.

As regards phase 2, the workshop outputs will be critically examined and evaluated to generate a design brief and intervention specification. This will detail the aim of the intervention, the design features it will include and how these will be operationalised, overall constituting the prototype intervention. A logic model, including a graphical and textual representation of how the intervention is intended to work, linking outcomes with processes and the underlying theoretical assumptions will be developed.52

Phase 3: health economic assessment

An early-stage health technology assessment will be undertaken to assess the feasibility of the prototype intervention. This will involve developing an Excel-based economic model that compares resource utilisation and outcomes from the routine survivorship care pathway (i.e. standard of care) with the proposed intervention. In order to understand the standard of care comparator pathway, a pragmatic review of cancer survivorship literature will be undertaken and combined with expert elicitation techniques from a range of stakeholders. This will involve overlap with phase 1 and 2 data collection methods as well as further independent evidence gathering, including focussed discussions or a brief survey with health professionals who care for patients with LIGGs.

The intervention pathway will include resource utilisation associated with the delivery and follow-up of the supported self-management programme. Expected clinical and QoL outcomes will also be included. The programme characteristics will be costed using a microcosting framework, itemising each identified component of the implementation and sustainability of the programme. Resource utilisation consistent with the programme features will also be costed using national reference costing approaches. Expected changes to resource utilisation, and disease-specific and QoL outcomes will be explored through expert elicitation techniques guided by available evidence on self-management programmes for cancer survivors.

The disaggregated costs and benefits of implementing the self-management programme, compared with the current care pathway will be analysed and reported, consistent with a cost-consequence analytical framework. Costs will be reported in 2020 (£). A deterministic cost-effectiveness analysis will also be highlighted using average costs and effects across both the intervention and the current care pathways; the base case analysis will adopt an NHS healthcare payer perspective. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios describing the ratio of cost difference to effectiveness difference for the range of outcomes identified will be estimated and reported for the base case analysis along with a series of sensitivity and scenario analyses, including the adoption of a societal cost perspective. The net benefit of the intervention will also be examined and a summary of the drivers of uncertainty in costs and benefits will be presented.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement (PPI) panel comprising brain tumour survivors and informal carers who support a brain tumour survivor has been established. We have also consulted members of The Brain Tumour Charity’s RIN. Throughout Ways Ahead, patients will be consulted on the design and conduct of research activities, as well as the interpretation and dissemination of findings. To date, PPI input has been obtained on the protocol, study information sheets (including appropriateness and sensitivity of language), topic guides and the study website.

As the project progresses, the panel will be invited to: comment and reflect on findings from the interviews; identify what they see as the key messages that need to be disseminated to survivors, informal carers and the public; co-design the lay summary of findings; and advise on other dissemination activities. They will also be invited to contribute to the design of the supported self-management programme (via the co-production workshops).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics and safety

All data from the interviews and workshops will be treated with strict confidence, anonymised, password protected and stored in secure facilities at the Population Health Sciences Institute at Newcastle University. Detailed information sheets will preface participation. Participants who provide informed consent (which will be written for face-to face interviews/workshops and audio-recorded when these take place remotely) and meet the inclusion criteria will be assigned a pseudonym. Any identifiable data will be stored securely behind the NHS firewall, using REDCap software, which is Health and Social Care Network (HSCN) compliant and only accessible to authorised members of the study team.

Dissemination plan

Study findings will be prepared for a range of stakeholder audiences. The study website has been established (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/waysahead/), which will be used to disseminate all outputs and materials.

For scientific dissemination, findings will be presented at relevant national and international conferences. Papers will be submitted to journals in neuro-oncology, cancer survivorship and psycho-oncology/behavioural science.

For lay dissemination, participants will have the option to receive a lay summary of the results. To reach patient and general populations, updates will be posted on the study website, with key messages (crafted together with the PPI Panel) highlighted. We will also embed podcasts within the website, with members of the team talking about the study, what it means and what survivors can do to self-manage. We will also seek to discuss the study findings with Brain and Central Nervous System Expert Advisory Groups in Cancer Alliances across different regions. Finally, we will hold a dissemination event for all stakeholders.

Discussion

Little research has been conducted to understand people’s everyday experiences of living with and managing a LIGG. Previous research has tended to combine people with low-grade and high-grade gliomas.53–58 Since those with high-grade gliomas face different symptoms, significantly shorter life-expectancy and tend to be older, these findings are insufficient to inform an intervention aimed at LIGGs. To address this evidence gap, and inform the development of a supported self-management programme, this study will generate considerable empirical data on the experiences of those living with a LIGG, both survivors and informal carers.

To date, self-management interventions in cancer have tended to focus on either breast or prostate cancer survivors59 60—where prognosis is very good—or aimed, more broadly, at survivors of common types of cancer.61 Far less is known about the self-management needs resulting from cancers with more complex/challenging outcomes, such as those experienced by people with LIGGs. Arguably, these groups need programmes specifically targeted to their complex needs and experiences, particularly since targeted self-management interventions have been found to be successful.62

It is also increasingly recognised that interventions which are systematically developed from the bottom-up, based on evidence and theoretically-informed are more likely to be effective.27 28 By adopting this approach in the Ways Ahead study, we will be able to identify the factors affecting a patient’s capacity to self-manage. From this, the theoretical constructs can be selected, and we can determine what BCTs are likely to be effective in addressing these constructs. Consequently, we can then evaluate why any behavioural changes have occurred in future testing of the prototype.

The Ways Ahead study responds to NHS England’s recommendations that cancer patients be provided with information and education to prepare for self-management, including advice on healthy lifestyles, information on managing the long-term side effects of treatment, signposting to rehabilitation, work and other support services.63 The study is also consistent with the objectives of the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative, which moved the focus of cancer care from treatment delivery to recovery, health and well-being,64 and the English Cancer Strategy, which aspires to a recovery package being available to every person with cancer by 2020.65

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Morven Brown, Tumi Sotire, Fiona Beyer and Catherine Richmond for their assistance with the systematic review, which forms a part of the Ways Ahead study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LS, JL, SW, RB, PG, VAS and TF developed the idea for the study and secured the funding. BR, LD and LS developed the detailed protocol. LS is the Chief Investigator. BR and LD will conduct the fieldwork. JL and SW will facilitate recruitment. RB, PG, VAS and TF will provide methodological input and expertise. BR drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by The Brain Tumour Charity, grant number: GN-000435.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.cancer research UK Brain, other CNS and intracranial tumours statistics, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu R, Page M, Solheim K, et al. . Quality of life in adults with brain tumors: current knowledge and future directions. Neuro Oncol 2009;11:330–9. 10.1215/15228517-2008-093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boele FW, Klein M, Reijneveld JC, et al. . Symptom management and quality of life in glioma patients. CNS Oncol 2014;3:37–47. 10.2217/cns.13.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Brain Tumour Charity Losing myself: the reality of life with a brain tumour. Farnborough: The Brain Tumour Charity, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox SW, Lyon D, Farace E. Symptom clusters in patients with high-grade glioma. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:61–7. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford E, Catt S, Chalmers A, et al. . Systematic review of supportive care needs in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol 2012;14:392–404. 10.1093/neuonc/nor229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan F, Amatya B. Factors associated with long-term functional outcomes, psychological sequelae and quality of life in persons after primary brain tumour. J Neurooncol 2013;111:355–66. 10.1007/s11060-012-1024-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackworth N, Fobair P, Prados MD. Quality of life self-reports from 200 brain tumor patients: comparisons with Karnofsky performance scores. J Neurooncol 1992;14:243–53. 10.1007/BF00172600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janda M, Steginga S, Langbecker D, et al. . Quality of life among patients with a brain tumor and their carers. J Psychosom Res 2007;63:617–23. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keir ST, Calhoun-Eagan RD, Swartz JJ, et al. . Screening for distress in patients with brain cancer using the NCCN's rapid screening measure. Psychooncology 2008;17:621–5. 10.1002/pon.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang ME, Wartella J, Kreutzer J, et al. . Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with brain tumours: a review of the literature. Brain Inj 2001;15:843–56. 10.1080/02699050010013653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, et al. . Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol 2002;57:41–9. 10.1023/A:1015728825642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L. Psychosocial and supportive-care needs in high-grade glioma. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:884–91. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70230-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langbecker D, Janda M. Systematic review of interventions to improve the provision of information for adults with primary brain tumors and their caregivers. Front Oncol 2015;5:1. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, et al. . Self-Management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:177–87. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Silva D. Helping people help themselves: a review of the evidence considering whether it is worthwhile to support self-management. Health Foundation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A, Vasta R. Annals of child development : Six theories of child development. Vol. 6 JAI Press Greenwich, CT, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce G, Parke HL, Pinnock H, et al. . The prisms taxonomy of self-management support: derivation of a novel taxonomy and initial testing of its utility. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016;21:73–82. 10.1177/1355819615602725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dwarswaard J, Bakker EJM, van Staa A, et al. . Self-Management support from the perspective of patients with a chronic condition: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Health Expect 2016;19:194–208. 10.1111/hex.12346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vassilev I, Rogers A, Kennedy A, et al. . The influence of social networks on self-management support: a metasynthesis. BMC Public Health 2014;14:719. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, et al. . Self-Management education for patients with cancer: evidence summary. Toronto (ON: Cancer Care Ontario, 2016: 20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster C, Calman L, Grimmett C, et al. . Managing fatigue after cancer treatment: development of restore, a web-based resource to support self-management. Psychooncology 2015;24:940–9. 10.1002/pon.3747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulman-Green D, Jeon S. Managing cancer care: a psycho-educational intervention to improve knowledge of care options and breast cancer self-management. Psychooncology 2017;26:173–81. 10.1002/pon.4013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Berg SW, Gielissen MFM, Custers JAE, et al. . Breath: web-based self-management for psychological adjustment after primary breast Cancer—Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JCO 2015;33:2763–71. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.9386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krouse RS, Grant M, McCorkle R, et al. . A chronic care ostomy self-management program for cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2016;25:574–81. 10.1002/pon.4078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M, Zrim S, Lawn S, et al. . A pilot study of Self-Management-based nutrition and physical activity intervention in cancer survivors. Nutr Cancer 2016;68:762–71. 10.1080/01635581.2016.1170169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:587–92. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E, et al. . Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029954. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Brien N, Heaven B, Teal G, et al. . Integrating evidence from systematic reviews, qualitative research, and expert knowledge using co-design techniques to develop a web-based intervention for people in the retirement transition. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e210. 10.2196/jmir.5790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casp U. Critical appraisal skills programme: checklists, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joanna Briggs Institute The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: checklist for quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies), 2017. Available: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/critical-appraisal-tools.JBI_QuasiExperimental_Appraisal_Tool2017.pdf

- 33.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG, et al. . The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a "state of the science" review. Neuro Oncol 2014;16:896–913. 10.1093/neuonc/nou087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forst DA, Nahed BV, Loeffler JS, et al. . Low-Grade gliomas. Oncologist 2014;19:403–13. 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauchet L. Epidemiology of diffuse low grade gliomas. Diffuse low-grade gliomas in adults. Springer, 2017: 13–53. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dixit K, Raizer J. Newer strategies for the management of low-grade gliomas. Oncology 2017;31:680–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claus EB, Walsh KM, Wiencke JK, et al. . Survival and low-grade glioma: the emergence of genetic information. Neurosurg Focus 2015;38:E6. 10.3171/2014.10.FOCUS12367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Epidemiology and etiology of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 2005;109:93–108. 10.1007/s00401-005-0991-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Affronti ML, Randazzo D, Lipp ES, et al. . Pilot study to describe the trajectory of symptoms and adaptive strategies of adults living with low-grade glioma. Semin Oncol Nurs 2018;34:472–85. 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dworkin SL. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Arch Sex Behav 2012;41:1319–20. 10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2019;2:1–16. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, et al. . Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students & Researchers. Sage Publications, Inc, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019;11:589–97. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yun YH, Jung JY, Sim JA, et al. . Patient-Reported assessment of self-management strategies of health in cancer patients: development and validation of the smart management strategy for health assessment tool (SAT). Psychooncology 2015;24:1723–30. 10.1002/pon.3839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunne S, Mooney O, Coffey L, et al. . Self-Management strategies used by head and neck cancer survivors following completion of primary treatment: a directed content analysis. Psychooncology 2017;26:2194–200. 10.1002/pon.4447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:37. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. . Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010;8:63. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. . The behavior change technique taxonomy (V1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:81–95. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mills T, Lawton R, Sheard L. Advancing complexity science in healthcare research: the logic of logic models. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:55. 10.1186/s12874-019-0701-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janda M, Eakin EG, Bailey L, et al. . Supportive care needs of people with brain tumours and their carers. Support Care Cancer 2006;14:1094–103. 10.1007/s00520-006-0074-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, et al. . Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. CMAJ 2012;184:E373–82. 10.1503/cmaj.111622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SC, et al. . Adjustment and support needs of glioma patients and their relatives: serial interviews. Psychooncology 2013;22:1299–305. 10.1002/pon.3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cavers DG. Understanding the supportive care needs of glioma patients and their relatives: a qualitative longitudinal study, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ownsworth T, Chambers S, Hawkes A, et al. . Making sense of brain tumour: a qualitative investigation of personal and social processes of adjustment. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2011;21:117–37. 10.1080/09602011.2010.537073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strang S, Strang P. Spiritual thoughts, coping and 'sense of coherence' in brain tumour patients and their spouses. Palliat Med 2001;15:127–34. 10.1191/026921601670322085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-Management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1585–95. 10.1007/s00520-017-3999-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim SH, Kim K, Mayer DK. Self-Management intervention for adult cancer survivors after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:719–28. 10.1188/17.ONF.719-728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim AR, Park H-A. Web-Based self-management support interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;216:142–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, et al. . Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 63.NHS England Implementing the cancer Taskforce recommendations: commissioning person centred care for people affected by cancer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and National Health Service Improvement . The National cancer survivorship initiative vision. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taskforce IC. Achieving World-class cancer outcomes. A strategy for England 2015-2020. Independent Cancer Taskforce 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valaitis R, Longaphy J, Ploeg J, et al. . Health TAPESTRY: co-designing interprofessional primary care programs for older adults using the persona-scenario method. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:122. 10.1186/s12875-019-1013-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Bono E. Six thinking hats, back Bay books. 2 edn, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.