Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was originally devised as a novel diagnostic technique to enable endoscopists to stage malignancies and acquire tissue. However, it rapidly advanced toward therapeutic applications and has provided gastroenterologists with the ability to effectively treat and manage advanced diseases in a minimally invasive manner. EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has gained considerable attention as an approach to provide relief in malignant and benign biliary obstruction for patients when endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) fails or is not feasible. Such instances occur in those with surgically altered anatomy, gastroduodenal obstruction, periampullary diverticulum or prior transampullary duodenal stenting. While ERCP remains the gold standard, a multitude of studies are showing that EUS-BD can be used as an alternative modality even in patients who could successfully undergo ERCP. This review will shed light on recent EUS-guided advancements and techniques in malignant and benign biliary obstruction.

Keywords: diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy, biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography, endoscopic ultrasonography, stents

Introduction

For the management of malignant biliary obstruction (MBO), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with transpapillary stenting is the gold standard for providing symptomatic relief and biliary decompression. While ERCP is a widely used and effective technique, its success can be hindered in up to 10% of patients because of surgically altered anatomy (SAA), periampullary diverticulum, large tumour involvement of the papilla, prior duodenal stenting or duodenal stenosis.1–4 Historically, when ERCP failed, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) was the conventional rescue therapy. However, its use is associated with high morbidity and a significantly reduced quality of life.5

Since its introduction in 2001, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has evolved as a reliable alternative in cases where conventional ERCP is unsuccessful.6 Randomised comparative trials and meta-analyses of EUS-BD and PTBD have demonstrated that while clinical and technical success show comparable efficacy, there are lower rates of reintervention and fewer post procedure adverse events (AEs) with EUS-BD.5 7 8 For instance, one randomised trial conducted by highly experienced endoscopists showed that compared with PTBD, EUS-BD demonstrated fewer procedure-related AEs (31% vs 9%) in addition to lower frequencies of unscheduled reintervention (0.93 vs 0.34).9

In addition to MBO, EUS-guided treatment has increasingly been incorporated in managing benign biliary diseases (BBD). While data are still limited, EUS-BD can provide a unique window of opportunity to treat patients with BBD, especially in those with SAA in cases where ERCP is not feasible. A recent long-term, multicentre study (with median follow-up 749 days) demonstrated the safety and feasibility of such an approach.10

Hence, with increasing operator use, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that EUS-BD may emerge as first-line therapy in treating MBO. Furthermore, its role in managing benign biliary obstruction is evolving with the advent of new step-by-step techniques. The focus of this review is to compare and describe recent advancements in EUS-BD and ERCP treatment modalities for managing malignant and benign biliary obstruction.

EUS-BD Techniques

EUS-guided biliary interventions can be accomplished through three different methods via a rendez-vous (RV), antegrade or transluminal (intrahepatic or extrahepatic) route. Of note, there is still insufficient evidence to determine which of the routes should be used.11

Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Rendezvous Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

EUS-RV is typically reserved as salvage therapy after failed ERCP with biliary access in patients with intact gastroduodenal anatomy. It involves transgastric, transduodenal short (second portion of duodenum), or transduodenal long (duodenal bulb) creation of a temporary pathway in which a guidewire is advanced through the biliary tree across the ampulla and into the duodenum in order to achieve access to allow conventional ERCP (figure 1). Unfortunately, EUS-RV has a limited success rate, with one prospective study reporting overall success and AE rates of 80% and 11.6%, respectively.12 Similarly, in comparing the technique among 247 published cases, EUS-RV was found to have an overall success rate of 74% with an 11% incidence of AEs—including major AEs of bleeding, bile leakage, peritonitis, pneumoperitoneum and pancreatitis.13 In general, this method is better served for managing BBD, particularly for patients with bile duct stones and post-cholecystectomy bile leaks.14

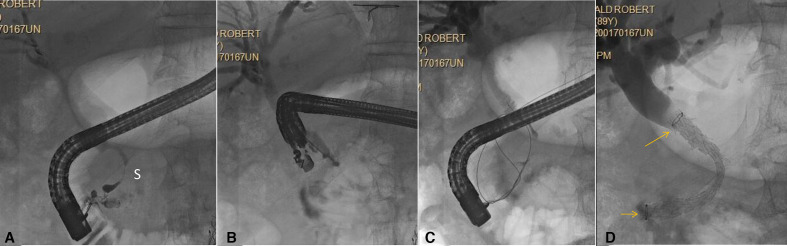

Figure 1.

Biliary rendezvous. Patient with history of chronic pancreatitis, CBD stricture (S) and failed ERCP. (A) ERCP shows distal CBD stricture (S). Deep cannulation failed; (B) EUS-guided injection for rendezvous. Note the needle is pointing distally, which is optimal for this approach; (C) wire passed antegrade into the duodenum; (D) duodenoscope has been reinserted and covered self-expandable metal stent is placed transpapillary (stent ends seen at arrows). CBD, common bile duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound.

Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Choledochoduodenostomy and Hepaticogastrostomy Biliary Drainage

Direct drainage methods include antegrade stenting through a transpapillary or transanastomotic fashion or transmural drainage via choledochoduodenostomy (CDS) or hepaticogastrostomy (HGS).

Antegrade stenting involves a transgastric puncture into the left intrahepatic biliary system with passage of a guidewire into the duodenum. The track is dilated to allow passage of a stent into the bile duct and across the papilla without creating an anastomosis at the puncture site. There are limited data involving antegrade stenting, though pooled studies have demonstrated an overall technical success rate of 77% and associated AE rate of 5%, including hepatic haematoma and pancreatitis.15–20 This approach is not commonly used and is generally believed to be inferior to transmural drainage.8 Reasons for this may include the complicated and cumbersome nature of guidewire placement and the theoretical concern for peritoneal bile leakage at the site of puncture.8 11 Yet, it appears that the antegrade technique is best suited for cases where ERCP is not possible in the setting of duodenal stenosis secondary to a periampullary tumour, SAA or an anastomosis site.17 21 22

As seen in figure 2, HGS access typically involves the creation of a fistula from the gastric cardia or lesser curvature of the stomach to a left intrahepatic duct, while CDS (figure 3) creates a fistula between the duodenum and extrahepatic bile duct.1 23 In cases of malignant distal common bile duct obstruction, both transmural routes are preferred and have demonstrated technical success rates up to 95%; however, at this point, there is no clear consensus on what method should be favoured.6 8 23–28 In an effort to compare the two methods, a prospective randomised trial of 49 patients (25 HGS, 24 CDS) found that while both techniques were similar in efficacy and safety, there was higher clinical success in the HGS cohort at the expense of slightly more AEs (table 1), however, these outcomes were not statistically significant.29

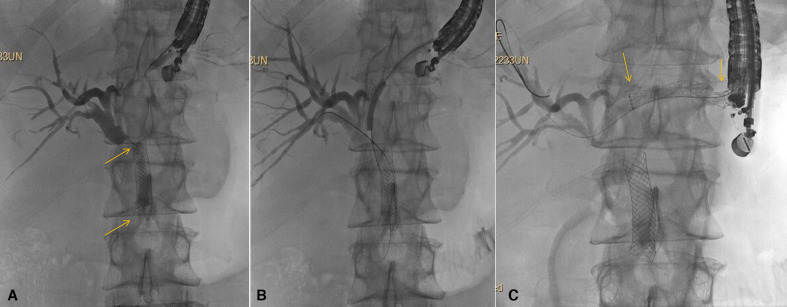

Figure 2.

Hepaticogastrostomy (HGS). Patient with pancreatic cancer for more than 1 year and prior ERCP with metal stent placement (stent ends seen at arrows). Now with occluded stent and complete duodenal obstruction due to cancer progression. (A) Transgastric puncture and cholangiogram show indwelling self-expandable metal biliary stent (stent ends seen at arrows) with tumour overgrowth and tumour ingrowth; (B) Guidewire passage into the biliary tree with balloon dilation being performed. Note balloon dilation always begins well distal to the puncture site and progresses proximally; (C) Placement of covered self-expandable metal stent across the HGS (stent ends seen at arrows). A 7 Fr double pigtail was subsequently placed through the SEMS (not shown). Note, the patient underwent endoscopic gastrojejunostomy at the same session following HGS. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SEMS, self-expanding metal stents.

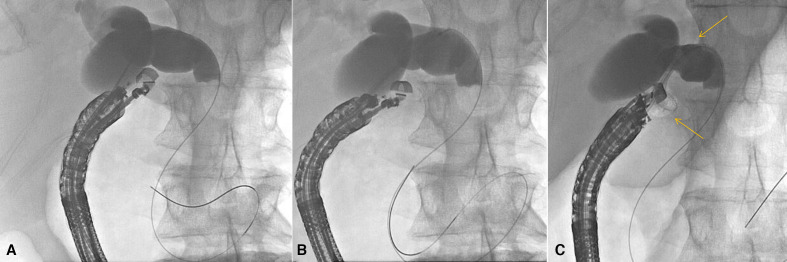

Figure 3.

Choledochoduodenostomy. Patient with malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP due to periampullary mass. (A) Transduodenal injection of contrast followed by wire placement. Note in this case the wire passes distally in the duct but preferably is passed proximally toward the bifurcation; (B) the delivery system of a cautery-enhanced LAMS is passed into the bile duct; (C) radiograph immediately after deployment of LAMS across choledochoduodenostomy (stent ends seen at arrows). A 7Fr double pigtail was subsequently placed through the LAMS (not shown). ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; LAMS, lumen-apposing metal stents.

Table 1.

Summary of studies comparing CDS versus HGS

| Author (year) | Study design | Total no subjects | Type of stent used (n=#) | Technical success CDS versus HGS rate, % (n=#) | Clinical success CDS versus HGS rate, % (n=#) | Total adverse events CDS versus HGS rate, % (n=#) |

| Kim34 (2012) |

Single Centre, Retrospective | 13 (9 CDS; 4 HGS) | SEMS (13) | 100 (9/9) vs 75 (3/4) | 100% (9/9) vs 50 (2/4) | 22 (3/9) vs 50 (2/4) |

| Prachayakul35 (2013) | Single Centre, Retrospective | 21 (6 CDS; 15 HGS) | SEMS (21) | 100 (6/6) vs 93 (14/15) | 100 (6/6) vs 93 (14/15) | 33 (2/6) vs 0 |

| Kawakubo36 (2014) | Multicentre, Retrospective | 64 (44 CDS; 20 HGS) | Plastic (27) pigtail (8) and SEMS (26) | 95 (42/44) vs 95 (19/20) | 93 (41/44) vs 95 (19/20) | 15 (7/44) vs 4 (7/20) |

| Park37 (2015) |

Multicentre, Prospective | 32 (12 CDS; 20 HGS) | SEMS (16) Hybrid Metal Stent (16) | 92 (11/12) vs 100 (20/20) | 92 (11/12) vs 90 (18/20) | 33 (4/12) vs 25 (5/20) |

| Artifon29 (2015) |

Single Centre, RCT | 49 (24 CDS; 25 HGS) | SEMS (49) | 91 (22/24) vs 96 (24/25) | 70 (17/24) vs 88 (22/25) | 13 (3/24) vs 20 (5/25) |

| Khashab38 (2016) | Multicentre, Retrospective | 121 (60 CDS; 61 HGS) | SEMS (109), Plastic (12) | 93 (56/60) vs 92 (56/61) | 85 (51/60) vs 82 (50/61) | 13 (8/60) vs 20 (12/61) |

| Guo39 (2016) |

Single Centre, Retrospective | 21 (14 CDS; 7 HGS) | SEMS (21) | 100 (14/14) vs 100 (7/7) | 100 (14/14) vs 100 (7/7) | 14 (2/14) vs 14 (1/7) |

| Ogura40 (2016) |

Single Centre, Retrospective | 39 (13 CDS; 26 HGS) | SEMS (39) | 100 (13/13) vs 100 (26/26) | 100 (13/13) vs 92 (24/26) | 46 (6/13) vs 8 (2/26) |

| Amano41 (2017) |

Single Centre, Prospective | 20 (11 CDS; 9 HGS) | CSEMS (20) | 100 (11/11) vs 100 (9/9) | 100 (11/11) vs 100 (9/9) | 18 (2/11) vs 11 (1/9) |

| Cho42 (2017) |

Single Centre, Prospective | 54 (33 CDS; 21 HGS) | CSEMS (54) | 100 (33/33) vs 100 (21/21) | 100 (33/33) vs 86 (18/21) | 15 (5/33) vs 19 (4/21) |

CDS, choledochoduodenostomy; CSEMS, covered self-expanding metal stents; HGS, hepaticogastrostomy; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SEMS, self-expandable metal stents.

In an effort to further evaluate these two methods, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have set out to compare these intrahepatic and extrahepatic approaches and have found largely similar technical and clinical success rates.30–33 In addition, overall AE rates ranged from 16% to 29%.30–33 In terms of which approach is safer, there remains conflicting data.29 34–42 One subgroup analysis reported less frequent rates of AE when using the extrahepatic approach.31 On the other hand, another study reported higher AE rates for the transhepatic route (30.5% vs 9.3%) without any differences in success rates.43 Yet, another meta-analysis and randomised prospective trial found that both routes displayed similar safety profiles.44 In cases of duodenal obstruction, it has been suggested that HGS may provide longer periods of stent patency with fewer AEs.40 Consequently, a Japanese multicentre study, in which 54/64 subjects underwent EUS-BD (40 CDS, 14 HGS) due to periampullary tumour invasion, found higher rates of stent dysfunction (32% vs 21%) and 3-month dysfunction-free stent patency (51% vs 80%) were observed in the HGS cohort compared with the CDS group, respectively.36 In light of these findings, it has been suggested that the technical feasibility of a CDS approach may be preferred in cases where the second part of the duodenum is affected, while the HGS route preferred when there is tumour invasion at the duodenal bulb.14 At our centre, we prefer to use HGS, especially when the patient is a candidate for curative pancreaticoduodenectomy as some surgeons have suggested that a transduodenal approach may make resection more technically difficult.

Learning Curve

An important consideration that may explain the heterogeneity in these findings is the steep learning curve with EUS-BD, and as a result, the more recent studies demonstrate lower AE rates.1 For example, one centre found a declining rate in AEs from 53% in the first 3 years to 22% in the last year of the study.45 Additionally, a single-centre study reported interesting data that show a significant reduction in morbidity over time, as one endoscopist gained more experience.46 During the first 5 years of the study, there were five procedure-related deaths in the first 50 patients treated. However, over the next 2 years, there was only one procedure-related death in the subsequent 51 patients.46 Using an HGS approach, another study proposed that 33 cases were needed in order for an endoscopist to achieve the technical proficiency needed to reduce procedure duration and AE.47 In terms of comparing HGS and CDS approaches over time, it has been reported that studies published after 2013 demonstrated higher success rates with fewer AEs.30

Types of Stents

While a learning curve seems to influence EUS-guided BD procedure outcomes, the type of stents used may also influence clinical, technical and AE rates. It is evident that the evolution of stent selection in treating MBO has influenced overall procedure rates. Due to issues with stent patency, plastic stents were initially used but quickly replaced by covered self-expanding metal stents (CSEMS) which offered better qualities of stent patency and improved BD owing to their larger diameters.28 48 49 Most importantly, these stents minimise bile leakage at the anastomotic site. In addition, CSEMSs also prevent tissue hyperplasia and make it easier for an endoscopist to conduct stent revision, when needed.48 One meta-analysis showed that compared with plastic stents, metal stents were significantly associated with lower AE rates (17% vs 31%).30

One cause for recurrent biliary obstruction following EUS-BD is stent migration. Recent advancements in metal stents have lowered these stent-related AEs.50 Yet, the use of large calibre stents can cause hyperplasia, making stent removal and reintervention difficult. To further examine this, a recent prospective study deployed smaller, 6 mm diameter CSEMS using the HGS method, and reported that 50% (10/20) of patients experienced obstruction due to biliary sludge (n=6) and stent dislocation (n=4).51 Reassuringly, a new stent was successfully inserted in 9/10 cases. While this was not a direct comparison to ERCP methods, this additional data provide further support that in scenarios in which there is papillary inaccessibility or failed cannulation secondary to duodenal obstruction or altered anatomy, EUS-BD can indeed serve as a reliable salvage method, and potentially a primary modality, in managing MBO.8 23

However, due to their larger size, tubular shape and rigid properties CSEMS may result in stent migration.52–54 As a result, the development and application of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) created a new opportunity to theoretically decrease stent migration, bile leak and reduce AEs. LAMS are short, dumbbell shaped stents composed of braided nitinol wire, covered with silicone and flanked with anti-migratory flanges that enable the device to anchor itself between non-adherent lumens and prevent tissue overgrowth.1 52 55 Newer versions of LAMS have an added advantage of an electrocautery-enhanced delivery system (EC-LAMS) which provides puncture and stent releases in a single step.1 56

This all comes in to play because the majority of EUS-BD studies have reported using CSEMS. However, LAMS are increasingly being used. There have been several, recent LAMS studies that have reported technical and clinical success rates ranging from 88.5% to 100% and 94.6% to 100%, respectively.56–60 A subgroup meta-analysis of five studies (involving 201 subjects) using EC-LAMS, demonstrated favourable technical (93.8%) and clinical (95.9%) success with a 5.6% postprocedure AEs rate.61 Thanks to its efficient, one step deployment technique, LAMSs have also been associated with shorter procedure times as well.56–59 One review, which analysed a total of 92 patients across 13 different studies, reported a 98.9% clinical success rate and 12 procedure related AEs (2 perforation, 1 bleeding, 7 stent obstruction and 1 stent migration).52 In France, a retrospective multicentre study of EUS-guided CDS with EC-LAMS reported the same rate of technical and clinical success (97.1%) with no short-term postprocedural AEs.60 The authors demonstrated that the use of direct fistulotomy, pure cut current, and 6 mm stent are reliable and safe techniques to follow.60 To date, there has been one preliminary study that directly compared LAMS to CSEMS.62 While LAMSa were indeed comparable to CSEMS, there was a faster learning curve—as measured by procedure time—towards the end of the study in the LAMS cohort (75 min vs 44.2 min).62 However, LAMS can only be used for the EUS-CDS approach since long-length CSEMS are needed for the HGS approach. For CDS, LAMSs have resulted in shorter procedure times, reliable efficacy and a good safety profile.56 58 The downside to LAMS is that their large flanges are often oversized for the duct as the 10 mm device has 21 mm flanges. Eight mm devices with smaller flanges are available outside the USA.

In an effort to overcome the large diameter and biflanged shape of LAMS, hybrid stents were specifically customised for EUS-BD in order to reduce the risk of stent migration and minimise the interruption of bile flow.42 By design, the proximal portion is uncovered to prevent obstruction of side branches, and the distal portion is covered with silicone-covered nitinol wire to prevent bile leakage.63 Additionally, both ends are equipped with antimigratory flaps to prevent stent migration.64 There is also a one-step metal stent placement delivery system—tailored for HGS and CDS procedures—that bypasses additional fistula dilation.64 In a randomised noninferiority study, Park et al showed this dedicated one-step device was technically feasible, safe and could shorten procedure times.37 Furthermore, studies investigating hybrid metal stents have demonstrated promising technical and clinical success rates of 100% and 95%, respectively.42 50 In a long-term study of 54 patients, stent migration was not observed over a median of 148.5 days.42

Which EUS-Guided Biliary Technique to choose:

In the context of the currently available literature, the optimal EUS method is still unclear. However, several approaches and EUS dedicated tools enable endoscopists to make a well-informed decision when factoring in personal expertise in relation to the patients’ disease (distal obstruction vs hilar) and anatomy (intact vs surgically altered), degree of duct dilation and stent patency.

EUS-BD versus ERCP in Malignant Biliary Obstruction

Currently, ERCP remains the gold standard and primary method for relief of MBO. Due to its wide use, familiarity and standardisation, ERCP BD in patients with native gastrointestinal and biliary anatomy has a remarkably low failure rate of <1% when conducted at high volume centres by an experienced endoscopist.65 66 When repeat ERCP is undertaken a recent guideline cited 442/537 (82%) were successfully completed with no difference in morbidity compared with those undergoing an initially successful ERCP.4 Repeating the procedure within 2–4 days is believed to provide improved bile duct visualisation due to decreased oedema and absence of submucosal injection as well as better overall multidisciplinary team preparation (ie, sedation, specialised guidewire availability and referral to another skilled endoscopist).4 Yet, ERCP is not without its own AEs and risks, with the most concerning major AE being post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).67 Although the incidence of PEP is relatively low (3.5%, range 1.6%–15.7%), it is associated with a significant degree of morbidity, financial costs and longer hospital stays.68–70 In addition, if EUS-BD is undertaken at the same session as ERCP, a delay in treatment care is avoided and may result in substantial cost savings for hospitalised patients.7 71

In the few instances of ERCP failure, presence of SAA or duodenal tumour invasion, EUS-BD is a viable alternative to PTBD. While success rates between ERCP and EUS-BD are similar, EUS-BD is associated with fewer AEs, lower reintervention rates and a higher degree of stent patency.72–75 A few recent EUS-BD meta-analyses reported promising rates of technical success (90%–94%), clinical success (87%–94%) and rates of AEs (16%–29%).30–32 Of note, one recent prospective study reported a 10% rate of AEs, which is likely due to more familiarity with the procedure.49

Recently, there have been three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing EUS-BD to ERCP. Two of these studies compared EUS-CDS to ERCP, and reported no significant differences in terms of technical (90.9%–93% vs 94.1%–100%) and clinical (93%–97% vs 91.2%–100%) success rates.74 75 In addition to reporting no difference in technical or clinical success, one meta-analysis comparing all three RCTs found that EUS-BD was associated with a lower rate of stent dysfunction requiring reintervention, tumour in-growth and postprocedure pancreatitis.76 This is important to highlight because a lower degree of stent reintervention may enable the oncologist to provide longer durations of uninterrupted systemic chemotherapy.76 Another meta-analysis involving 10 studies of 756 subjects reported a cumulative AE rate of 16.3% (54/331) and 18.3% (78/425) for EUS-BD and ERCP, respectively.69 While PEP is a major concern with ERCP, bile peritonitis is a feared complication in EUS-BD that has a reported incidence of 2.4%.69 In general, the majority of AEs are mild to moderate in severity, with one study reporting AEs in 21.2% (6.1% moderate severity) for EUS-BD subjects and 14.7% (5.9% moderate severity) in the ERCP cohort.

With growing evidence and better technical expertise, EUS-BD could indeed serve as first line therapy in distal MBO (table 2).14 77–80 A large study (n=208 subjects) comparing ERCP to EUS-BD, noted similar technical success rates (94% vs 93%) but notably lower rates of PEP (4.8% vs 0%) and shorter procedure times (30 min vs 36 min) in the EUS-BD cohort.77 A recent prospective study, involving 10 different Japanese centres, found that when EUS-CDS was compared with ERCP for primary BD, EUS-BD demonstrated high technical (97%) and functional (100%) success rates as well as shorter procedure times (25 min vs 52 min).81 Lastly, in a multicentre study involving 39 subjects with indwelling duodenal stents, EUS-BD displayed technical and clinical superiority over endoscopic transpapillary stenting with no major differences in AEs.82 Since EUS-BD approaches avoid traversing a diseased bile duct, they can theoretically provide longer periods of stent patency when compared with transpapillary stenting.

Table 2.

Summary of studies comparing EUS-BD to ERCP in malignant biliary obstruction

| Author (year) | Study design | Total no subjects | Type of EUS-BD | Type of stent used | Technical success EUS versus ERCP rate, % (n=#) | Clinical success EUS versus ERCP rate, % (n=#) | Total Adverse Events EUS-BD versus ERCP rate, % (n=#) |

| Tonozuka72 (2013) | Single Centre, Retrospective | 11 (8 EUS-BD; 3 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-HGS EUS‐CAS |

FCSEMS | 100 (8/8) vs 100 (3/3) | 100 (8/8) vs 100 (3/3) | 37.5 (3/8) vs 0 |

| Hamada78 (2014) | Multicentre, Retrospective | 20 (7 EUS-BD; 13 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-HGS |

SEMS Plastic |

— | — | 14 (1/7) vs 7.6 (1/13) |

| Dhir77 (2015) |

Multicentre, Retrospective | 208 (104 EUS-BD;104 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-AG |

FCSEMS UCSEMS |

93.3 (97/104) vs 94.2 (98/104) | 89.4 (93/104) vs 91.3 (95/104) | 8.7 (9/104) vs 8.7 (9/104) |

| Kawakubo80 (2016) | Single Centre, Retrospective | 82 (26 EUS-BD; 56 ERCP) | EUS-CDS | PCSEMS | - | 96.2 (25/26) vs 98.2 (55/56) | 26.9 (7/26) vs 35.7 (20/56) |

| Bang75 (2018) |

Single Centre, Prospective, RCT | 67 (33 EUS-BD; 34 ERCP) | EUS-CDS | FCSEMS | 90.9 (30/33) vs 94.1 (32/34) | 97 (32/33) vs 91 (31/34) | 21.2 (7/33) vs 14.7 (5/34) |

| Hamada79 (2018) | Multicentre, Retrospective | 110 (20 EUS; 90 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-HGS |

FCSEMS PCSEMS UCSEMS |

- | - | 35% (7/20) vs 8.8% (8/90) |

| Paik73 (2018) |

Multicentre, Prospective, RCT | 125 (64 EUS-BD; 61 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-HGS |

Hybrid PCSEMS | 93.8 (60/64) vs 90.2 (55/61) | 90 (54/60) vs 94.5 (52/55) | 10.9 (7/64) vs 39 (24/61) |

| Park74 (2018) |

Single Centre, Prospective, RCT | 28 (14 EUS-BD; 14 ERCP) | EUS-CDS | PCSEMS | 92.8 (13/14) vs 100 (14/14) | 92.8 (13/14) vs 100 (14/14) | 0 vs 0 |

| Yamao82 (2018) |

Multicentre, Retrospective | 39 (14 EUS-BD; 25 ERCP) | EUS-CDS EUS-HGS |

FCSEMS PCSEMS Plastic |

100 (14/14) vs 56 (14/25) | 92.9 (13/14) vs 52 (13/25) | 57 (8/14) vs 32 (8/25) |

| Nakai81 (2019) | Multicentre, Prospective | 59 (34 EUS-BD; 25 ERCP) | EUS-CDS | FCSEMS PCSEMS |

97 (33/34) | 100 (34/34) | 15 (5/34) |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-AG, EUS-guided antegrade stenting; EUS-BD, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage; EUS-CAS, EUS‐guided choledochoantrostomy; EUS-CDS, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy; EUS-HGS, EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy; FCSEMS, fully covered SEMS; PCSEMS, partially covered SEMS; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SEMS, self-expanding metal stents; UCSEMS, uncovered SEMS.

Benign Biliary Disease

As technical expertise and experience with EUS-BD continue to accumulate, many endoscopist are considering this approach as potential alternative to treat BBD in cases of ERCP failure or SAA. While successful stone extraction is achieved in more than 90% of cases with normal anatomy, anatomical changes can make ERCP extraordinarily difficult or impossible.83 Such examples include Roux-en-Y biliary anastomosis or gastric bypass and pancreaticoduodenectomy.84 While ERCP with balloon-assisted enteroscopy has been used to overcome anatomic restrictions, variable success rates have been reported ranging from 67% to 95%.11 84 85 Typically, PTBD is the salvage therapy. However, in addition to the high morbidity and reduced quality of life with PTBD, a recent international survey demonstrated that many patients (not surprisingly) would prefer internal BD over an external drain.86 As a result, a growing number of studies have explored EUS-BD role in managing BBD.10 11 21 83 87–92

Two initial small, single-centre studies reported a cumulative technical success rate of 63.6% (range, 60%–67%) with a total of 11 subjects undergoing stone removal in cases of SAA.11 83 A subsequent multicentre study involving 29 patients described a 72% technical success rate with only five reported AEs that were successfully managed conservatively.21 In that study, technical failure when using EUS antegrade stenting was attributed to failed bile duct puncture (n=6), unsuccessful guide wire manipulation (n=1) and failed stone extraction (n=1).21 Three recent studies demonstrated an improvement in procedural and clinical success ranging from 91.9% to 100%.87 89 90 In one of these studies by James et al, 20 patients with SAA due to Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses (RYGB) (n=9), Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (n=6), Billroth II procedures (n=2) and Whipple procedures (n=3) underwent EUS-BD through a transgastric or transjejunal approach.87 In addition to its promising 100% clinical success rate there were only three mild AE reported with no reported deaths during a follow-up.87 Furthermore, the study suggested that a hepaticojejunostomy approach may be preferred when treating patients with a partial gastrectomy or RYGB.87

Improving technical outcomes in patients with BBD has been aided by the introduction of a two-step EUS-guided drainage approach when stone extraction or biliary stricture access is difficult due to limited biliary ductal dilation or long distances for the guidewire to travel. Using this method, the first step involves stent placement (typically with EUS-HGS), followed by antegrade stone extraction once the fistula matures.93 One of the initial pilot studies using this approach in seven patients with anastomotic strictures reported clinical and technical success rates of 100% and 57%, respectively.91 In terms of AE, three stent migrations and three episodes of bleeding occurred. Another group applied this technique in nine patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy and achieved technical success in all subjects, with only one reported AE of cholangitis following prolonged lithotripsy.92 In the absence of an acute infection or pancreatitis, we recommend that EUS-guided gastrogastrostomy be considered in patients with RYGB anatomy. Initially described in 2014, this novel technique enables an endoscopist to exclude the stomach by creating a fistulous tract via LAMS in order for the duodenoscope to pass through so conventional ERCP can be utilised.94–96

At this point in time, there are currently no head to head studies comparing ERCP to EUS-BD in instances of BBD. However, it is generally agreed on that ERCP should remain the first line treatment option. In scenarios of SAA, enteroscopy-assisted ERCP should be strongly considered. Though when such attempts fail, EUS-BD is becoming a reliable option to PTBD. As more studies are conducted, the clinical success and safety profile of the two-step approach will likely catapult EUS-guided intervention as a potential first line tool in cases of SAA. Though standardisation of the procedure with dedicated devices are still needed.97 Additionally, a few contraindications to EUS-BD include severe coagulopathy, inability to visualise the biliary tract, and presence of intervening vessels or large volume ascites.23 97

Conclusion

EUS-guided BD is becoming an accepted approach for the relief of MBO when ERCP fails in centres with expertise. EUS-BD may eventually become accepted as a primary approach for malignant disease. EUS-BD is increasingly used for benign disease as an alternative to percutaneous approaches in centres with expertise. At the present time, patients with MBO or BBD should be evaluated on a case by case basis. Ultimately, EUS-BD expertise will be disseminated to community centres, though it is expected this will not occur for many years.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC: conception and design, generation, collection, assembly, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.THB: Conception and design, generation, collection, assembly, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: THB: consultant and speaker for Boston Scientific, WLG, Cook Endoscopy, Medtronic and Olympus America.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article.

References

- 1.Leung Ki E-L, Napoleon B. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage: a change in paradigm? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019;11:345–53. 10.4253/wjge.v11.i5.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SL, Perez-Miranda M, Kahaleh M, et al. Updates in therapeutic endoscopic ultrasonography. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018;52:765–72. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarantino I, Barresi L, Fabbri C. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012;4:306–11. 10.4253/wjge.v4.i7.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumonceau J-M, Tringali A, Papanikolaou IS, et al. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline - Updated October 2017. Endoscopy 2018;50:910–30. 10.1055/a-0659-9864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baniya R, Upadhaya S, Madala S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2017;10:67–74. 10.2147/CEG.S132004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy 2001;33:898–900. 10.1055/s-2001-17324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharaiha RZ, Khan MA, Kamal F, et al. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage in comparison with percutaneous biliary drainage when ERCP fails: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:904–14. 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukai S, Itoi T, Baron TH, et al. Indications and techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis in updated Tokyo guidelines 2018. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017;24:537–49. 10.1002/jhbp.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee TH, Choi J-H, Park DH, et al. Similar efficacies of endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous drainage for malignant distal biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1011–9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogura T, Takenaka M, Shiomi H, et al. Long-Term outcomes of EUS-guided transluminal stent deployment for benign biliary disease: multicenter clinical experience (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound 2019;8:398–403. 10.4103/eus.eus_45_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwashita T, Doi S, Yasuda I. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage: a review. Clin J Gastroenterol 2014;7:94–102. 10.1007/s12328-014-0467-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuno N, Hara K, Mizuno N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: which approach route is the best? Intern Med 2017;56:3135–43. 10.2169/internalmedicine.8677-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isayama H, Nakai Y, Kawakubo K, et al. The endoscopic ultrasonography-guided rendezvous technique for biliary cannulation: a technical review. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:413–20. 10.1007/s00534-012-0577-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: who, when, which, and how? World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1297–303. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artifon ELA, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ferreira FC, et al. EUS-guided antegrade transhepatic placement of a self-expandable metal stent in hepatico-jejunal anastomosis. JOP 2011;12:610–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Doi S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided antegrade treatments for biliary disorders in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:2417–22. 10.1007/s10620-013-2645-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen-Tang T, Binmoeller K, Sanchez-Yague A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transhepatic anterograde self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placement across malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy 2010;42:232–6. 10.1055/s-0029-1243858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park DH, Jeong SU, Lee BU, et al. Prospective evaluation of a treatment algorithm with enhanced guidewire manipulation protocol for EUS-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:91–101. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, et al. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:56–64. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park DH, Jang JW, Lee SS, et al. EUS-guided transhepatic antegrade balloon dilation for benign bilioenteric anastomotic strictures in a patient with hepaticojejunostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:692–3. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwashita T, Nakai Y, Hara K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided antegrade treatment of bile duct stone in patients with surgically altered anatomy: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2016;23:227–33. 10.1002/jhbp.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto K, Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, et al. EUS-guided antegrade metal stenting with hepaticoenterostomy using a dedicated plastic stent with a review of the literature (with video). Endosc Ultrasound 2018;7:404–12. 10.4103/eus.eus_51_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teoh AYB, Dhir V, Kida M, et al. Consensus guidelines on the optimal management in interventional EUS procedures: results from the Asian EUS group RAND/UCLA expert panel. Gut 2018;67:1209–28. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saad WEA, Wallace MJ, Wojak JC, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, biliary drainage, and percutaneous cholecystostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21:789–95. 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy in patients with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2008;14:6078–82. 10.3748/wjg.14.6078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, et al. Interventional EUS-guided cholangiography: evaluation of a technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:52–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horaguchi J, Fujita N, Noda Y, et al. Endosonography-guided biliary drainage in cases with difficult transpapillary endoscopic biliary drainage. Dig Endosc 2009;21:239–44. 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park DH, Koo JE, Oh J, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with one-step placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective feasibility study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2168–74. 10.1038/ajg.2009.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artifon ELA, Marson FP, Gaidhane M, et al. Hepaticogastrostomy or choledochoduodenostomy for distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP: is there any difference? Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:950–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Zhu J, Xing L, et al. Assessment of efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:1218–27. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan MA, Akbar A, Baron TH, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:684–703. 10.1007/s10620-015-3933-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moole H, Bechtold ML, Forcione D, et al. A meta-analysis and systematic review: success of endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary stenting in patients with inoperable malignant biliary strictures and a failed ERCP. Medicine 2017;96:e5154. 10.1097/MD.0000000000005154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabbri C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided treatments: Are we getting evidence based - a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:8424–48. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim TH, Kim SH, Oh HJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage with placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:2526–32. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prachayakul V, Aswakul P. A novel technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:4758–63. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kato H, et al. Multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2014;21:328–34. 10.1002/jhbp.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park DH, Lee TH, Paik WH, et al. Feasibility and safety of a novel dedicated device for one-step EUS-guided biliary drainage: a randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:1461–6. 10.1111/jgh.13027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Penas I, et al. International multicenter comparative trial of transluminal EUS-guided biliary drainage via hepatogastrostomy vs. choledochoduodenostomy approaches. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E175–81. 10.1055/s-0041-109083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo J, Sun S, Liu X, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage using a fully covered metallic stent after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016;2016:1–6. 10.1155/2016/9469472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogura T, Chiba Y, Masuda D, et al. Comparison of the clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy and hepaticogastrostomy for bile duct obstruction with duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy 2016;48:156–63. 10.1055/s-0034-1392859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amano M, Ogura T, Onda S, et al. Prospective clinical study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage using novel balloon catheter (with video). J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:716–20. 10.1111/jgh.13489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho DH, Lee SS, Oh D, et al. Long-term outcomes of a newly developed hybrid metal stent for EUS-guided biliary drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:1067–75. 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhir V, Artifon ELA, Gupta K, et al. Multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided expandable biliary metal stent placement: choice of access route, direction of stent insertion, and drainage route. Dig Endosc 2014;26:430–5. 10.1111/den.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uemura RS, Khan MA, Otoch JP, et al. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus Hepaticogastrostomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018;52:123–30. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Attasaranya S, Netinasunton N, Jongboonyanuparp T, et al. The spectrum of endoscopic ultrasound intervention in biliary diseases: a single center's experience in 31 cases. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/680753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poincloux L, Rouquette O, Buc E, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP: cumulative experience of 101 procedures at a single center. Endoscopy 2015;47:794–801. 10.1055/s-0034-1391988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh D, Park DH, Song TJ, et al. Optimal biliary access point and learning curve for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy with transmural stenting. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2017;10:42–53. 10.1177/1756283X16671671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu L, Tang X, Jin H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage using Self-Expandable metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2017;2017:1–10. 10.1155/2017/6284094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khashab MA, Van der Merwe S, Kunda R, et al. Prospective international multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E487–96. 10.1055/s-0042-102648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song TJ, Lee SS, Park DH, et al. Preliminary report on a new hybrid metal stent for EUS-guided biliary drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:707–11. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.05.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okuno N, Hara K, Mizuno N, et al. Efficacy of the 6-mm fully covered self-expandable metal stent during endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy as a primary biliary drainage for the cases estimated difficult endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a prospective clinical study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33:1413–21. 10.1111/jgh.14112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jain D, Shah M, Patel U, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided Choledocho-Enterostomy by using lumen Apposing metal stent in patients with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a literature review. Digestion 2018;98:1–10. 10.1159/000487185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prachayakul V, Aswakul P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage as an alternative to percutaneous drainage and surgical bypass. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015;7:37–44. 10.4253/wjge.v7.i1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park DH, Jang JW, Lee SS, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:1276–84. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binmoeller K, Shah J. A novel lumen-apposing stent for transluminal drainage of nonadherent extraintestinal fluid collections. Endoscopy 2011;43:337–42. 10.1055/s-0030-1256127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacques J, Privat J, Pinard F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy with electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing stents: a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy 2019;51:540–7. 10.1055/a-0735-9137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuchiya T, Teoh AYB, Itoi T, et al. Long-term outcomes of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy using a lumen-apposing metal stent for malignant distal biliary obstruction: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1138–46. 10.1016/j.gie.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderloni A, Fugazza A, Troncone E, et al. Single-stage EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy using a lumen-apposing metal stent for malignant distal biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:69–76. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kunda R, Pérez-Miranda M, Will U, et al. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant distal biliary obstruction using a lumen-apposing fully covered metal stent after failed ERCP. Surg Endosc 2016;30:5002–8. 10.1007/s00464-016-4845-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacques J, Privat J, Pinard F, et al. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy by use of electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stents: a French multicenter study after implementation of the technique (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92:134–41. 10.1016/j.gie.2020.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krishnamoorthi R, Dasari CS, Thoguluva Chandrasekar V, et al. Effectiveness and safety of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy using lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2020;34:2866–77. 10.1007/s00464-020-07484-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shah SL, Hajifathalian K, Issa D, et al. Tu1392 a multicenter matched comparative analysis of EUS-GUIDED biliary drainage with LUMEN-APPOSING metal stents versus fully covered metal stents. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:AB606 10.1016/j.gie.2019.03.1049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogura T, Higuchi K. Technical tips for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:3945–51. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.3945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leung Ki E-L, Napoleon B. EUS-specific stents: available designs and probable lacunae. Endosc Ultrasound 2019;8:S17–27. 10.4103/eus.eus_50_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ardengh JC, Lopes CV, Kemp R, et al. Different options of endosonography-guided biliary drainage after endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography failure. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018;10:99–108. 10.4253/wjge.v10.i5.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holt BA, Hawes R, Hasan M, et al. Biliary drainage: role of EUS guidance. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:160–5. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Logiudice FP, Bernardo WM, Galetti F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided vs endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography biliary drainage for obstructed distal malignant biliary strictures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019;11:281–91. 10.4253/wjge.v11.i4.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mine T, Morizane T, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Clinical practice guideline for post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2017;52:1013–22. 10.1007/s00535-017-1359-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han SY, Kim S-O, So H, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage versus ERCP for first-line palliation of malignant distal biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019;9:16551 10.1038/s41598-019-52993-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li D-F, Zhou C-H, Wang L-S, et al. Is ERCP-BD or EUS-BD the preferred decompression modality for malignant distal biliary obstruction? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2019;111:953–60. 10.17235/reed.2019.6125/2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Afghani E, et al. A comparative evaluation of EUS-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous drainage in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:557–65. 10.1007/s10620-014-3300-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tonozuka R, Itoi T, Sofuni A, et al. Endoscopic double stenting for the treatment of malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction due to pancreatic cancer. Dig Endosc 2013;25 Suppl 2:100–8. 10.1111/den.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paik WH, Lee TH, Park DH, et al. EUS-Guided biliary drainage versus ERCP for the primary palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:987–97. 10.1038/s41395-018-0122-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park JK, Woo YS, Noh DH, et al. Efficacy of EUS-guided and ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: prospective randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:277–82. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bang JY, Navaneethan U, Hasan M, et al. Stent placement by EUS or ERCP for primary biliary decompression in pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:9–17. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller CS, Barkun AN, Martel M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for distal malignant obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Endosc Int Open 2019;7:E1563–73. 10.1055/a-0998-8129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhir V, Itoi T, Khashab MA, et al. Multicenter comparative evaluation of endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for malignant distal common bile duct obstruction by ERCP or EUS-guided approach. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:913–23. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamada T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Transmural biliary drainage can be an alternative to transpapillary drainage in patients with an indwelling duodenal stent. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:1931–8. 10.1007/s10620-014-3062-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hamada T, Nakai Y, Lau JY, et al. International study of endoscopic management of distal malignant biliary obstruction combined with duodenal obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018;53:46–55. 10.1080/00365521.2017.1382567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawakubo K, Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy vs. transpapillary stenting for distal biliary obstruction. Endoscopy 2016;48:164–9. 10.1055/s-0034-1393179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Kawakami H, et al. Prospective multicenter study of primary EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy using a covered metal stent. Endosc Ultrasound 2019;8:111–7. 10.4103/eus.eus_17_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamao K, Kitano M, Takenaka M, et al. Outcomes of endoscopic biliary drainage in pancreatic cancer patients with an indwelling gastroduodenal stent: a multicenter cohort study in West Japan. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:66–75. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal in patients with surgically altered anatomy: case series and technical review (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2014;21:E86–93. 10.1002/jhbp.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saleem A, Baron T, Gostout C, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with altered Roux-en-Y anatomy. Endoscopy 2010;42:656–60. 10.1055/s-0030-1255557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Itoi T, Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, et al. TG13 indications and techniques for biliary drainage in acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:71–80. 10.1007/s00534-012-0569-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nam K, Kim DU, Lee TH, et al. Patient perception and preference of EUS-guided drainage over percutaneous drainage when endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage fails: an international multicenter survey. Endosc Ultrasound 2018;7:48–55. 10.4103/eus.eus_100_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.James TW, Fan YC, Baron TH. EUS-guided hepaticoenterostomy as a portal to allow definitive antegrade treatment of benign biliary diseases in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:547–54. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.2353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Kubota Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided antegrade bile duct stone treatment followed by direct peroral transhepatic cholangioscopy in a patient with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Endoscopy 2015;47:E340–1. 10.1055/s-0034-1392507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pizzicannella M, Caillol F, Pesenti C, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage for the management of benign biliary strictures in patients with altered anatomy: a single-center experience. Endosc Ultrasound 2020;9:45–52. 10.4103/eus.eus_55_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mukai S, Itoi T, Sofuni A, et al. EUS-guided antegrade intervention for benign biliary diseases in patients with surgically altered anatomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:399–407. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miranda-García P, Gonzalez JM, Tellechea JI, et al. EUS hepaticogastrostomy for bilioenteric anastomotic strictures: a permanent access for repeated ambulatory dilations? results from a pilot study. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E461–5. 10.1055/s-0042-103241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hosmer A, Abdelfatah MM, Law R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy and antegrade clearance of biliary lithiasis in patients with surgically-altered anatomy. Endosc Int Open 2018;6:E127–30. 10.1055/s-0043-123188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Koike K. Two-Step endoscopic ultrasonography-guided antegrade treatment of a difficult bile duct stone in a surgically altered anatomy patient. Dig Endosc 2018;30:125–7. 10.1111/den.12965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kedia P, Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, et al. Internal EUS-directed transgastric ERCP (edge): game over. Gastroenterology 2014;147:566–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Krafft MR, Hsueh W, James TW, et al. The EDGI new take on edge: EUS-directed transgastric intervention (EDGI), other than ERCP, for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass anatomy: a multicenter study. Endosc Int Open 2019;7:E1231–40. 10.1055/a-0915-2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang G, Liu X, Wang S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: a promising alternative to surgery. J Transl Int Med 2019;7:93–9. 10.2478/jtim-2019-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nakai Y, Kogure H, Isayama H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for benign biliary diseases. Clin Endosc 2019;52:212–9. 10.5946/ce.2018.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]