Abstract

Isoprene emitted by vegetation is an important precursor of secondary organic aerosol (SOA), but the mechanism and yields are uncertain. Aerosol is prevailingly aqueous under the humid conditions typical of isoprene-emitting regions. Here we develop an aqueous-phase mechanism for isoprene SOA formation coupled to a detailed gas-phase isoprene oxidation scheme. The mechanism is based on aerosol reactive uptake coefficients (γ) for water-soluble isoprene oxidation products, including sensitivity to aerosol acidity and nucleophile concentrations. We apply this mechanism to simulation of aircraft (SEAC4RS) and ground-based (SOAS) observations over the Southeast US in summer 2013 using the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model. Emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx ≡ NO + NO2) over the Southeast US are such that the peroxy radicals produced from isoprene oxidation (ISOPO2) react significantly with both NO (high-NOx pathway) and HO2 (low-NOx pathway), leading to different suites of isoprene SOA precursors. We find a mean SOA mass yield of 3.3 % from isoprene oxidation, consistent with the observed relationship of total fine organic aerosol (OA) and formaldehyde (a product of isoprene oxidation). Isoprene SOA production is mainly contributed by two immediate gas-phase precursors, isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX, 58% of isoprene SOA) from the low-NOx pathway and glyoxal (28%) from both low- and high-NOx pathways. This speciation is consistent with observations of IEPOX SOA from SOAS and SEAC4RS. Observations show a strong relationship between IEPOX SOA and sulfate aerosol that we explain as due to the effect of sulfate on aerosol acidity and volume. Isoprene SOA concentrations increase as NOx emissions decrease (favoring the low-NOx pathway for isoprene oxidation), but decrease more strongly as SO2 emissions decrease (due to the effect of sulfate on aerosol acidity and volume). The US EPA projects 2013–2025 decreases in anthropogenic emissions of 34% for NOx (leading to 7% increase in isoprene SOA) and 48% for SO2 (35% decrease in isoprene SOA). Reducing SO2 emissions decreases sulfate and isoprene SOA by a similar magnitude, representing a factor of 2 co-benefit for PM2.5 from SO2 emission controls.

Keywords: isoprene, SOA yield, IEPOX, glyoxal, SEAC4RS, SOAS, formaldehyde

1. Introduction

Isoprene emitted by vegetation is a major source of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) (Carlton et al., 2009, and references therein) with effects on human health, visibility, and climate. There is large uncertainty in the yield and composition of isoprene SOA (Scott et al., 2014; McNeill et al., 2014), involving a cascade of species produced in the gas-phase oxidation of isoprene and their interaction with pre-existing aerosol (Hallquist et al., 2009). We develop here a new aqueous-phase mechanism for isoprene SOA formation coupled to gas-phase chemistry, implement it in the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model (CTM) to simulate observations in the Southeast US, and from there derive new constraints on isoprene SOA yields and the contributing pathways.

Organic aerosol is ubiquitous in the atmosphere, often dominating fine aerosol mass (Zhang et al., 2007), including in the Southeast US where it accounts for more than 60% in summer (Attwood et al., 2014). It may be directly emitted by combustion as primary organic aerosol (POA), or produced within the atmosphere as SOA by oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Isoprene (C5H8) from vegetation is the dominant VOC emitted globally, and the Southeast US in summer is one of the largest isoprene-emitting regions in the world (Guenther et al., 2006). SOA yields from isoprene are low compared with larger VOCs (Pye et al., 2010), but isoprene emissions are much higher. Kim et al. (2015) estimated that isoprene accounts for 40% of total organic aerosol in the Southeast US in summer.

Formation of OA from oxidation of isoprene depends on local concentrations of nitrogen oxide radicals (NOx ≡ NO + NO2) and pre-existing aerosol. NOx concentrations determine the fate of organic peroxy radicals originating from isoprene oxidation (ISOPO2), leading to different cascades of oxidation products in the low-NOx and high-NOx pathways (Paulot et al., 2009a; 2009b). Uptake of isoprene oxidation products to the aerosol phase depends on their vapor pressure (Donahue et al., 2006), solubility in aqueous media (Saxena and Hildeman, 1996), and subsequent condensed-phase reactions (Volkamer et al., 2007). Aqueous aerosol provides a medium for reactive uptake (Eddingsaas et al., 2010; Surratt et al., 2010) with dependences on acidity (Surratt et al., 2007a), concentration of nucleophiles such as sulfate (Surratt et al., 2007b), aerosol water (Carlton and Turpin, 2013), and organic coatings (Gaston et al., 2014).

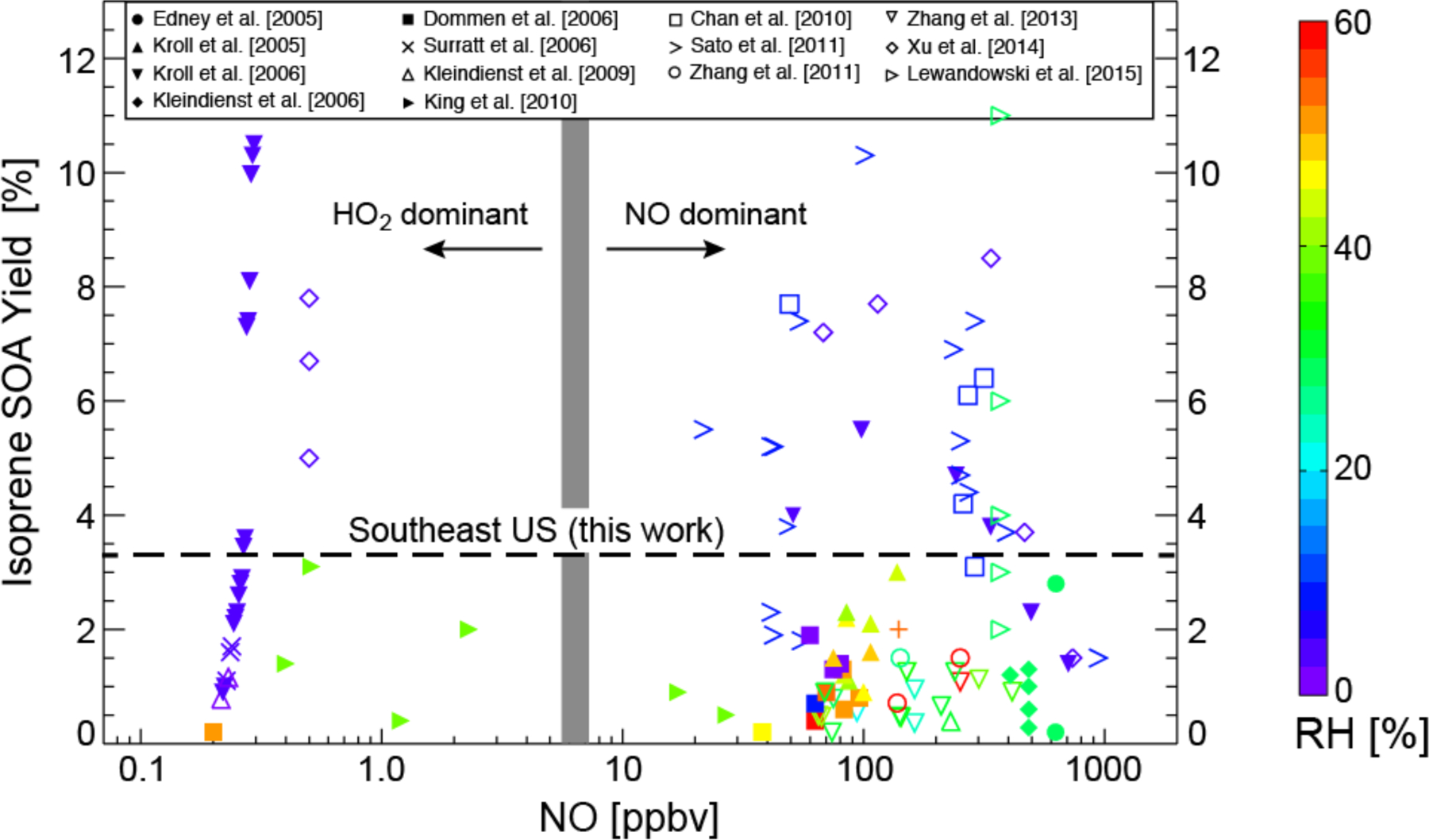

We compile in Fig. 1 the published laboratory yields of isoprene SOA as a function of initial NO concentration and relative humidity (RH). Here and elsewhere, the isoprene SOA yield is defined as the mass of SOA produced per unit mass of isoprene oxidized. Isoprene SOA yields span a wide range, from <0.1% to >10%, with no systematic difference between low-NOx and high-NOx pathways. Yields tend to be higher in dry chambers (RH < 10%). Under such dry conditions isoprene SOA is expected to be solid (Virtanen et al., 2010; Song et al., 2015). At humid conditions more representative of the summertime boundary layer, aerosols are likely aqueous (Bateman et al., 2014). Standard isoprene SOA mechanisms used in atmospheric models assume reversible partitioning onto pre-existing organic aerosol, fitting the dry chamber data (Odum et al., 1996). However, this may not be appropriate for actual atmospheric conditions where aqueous-phase chemistry with irreversible reactive uptake of water-soluble gases is likely the dominant mechanism (Ervens et al., 2011; Carlton and Turpin, 2013). Several regional/global models have implemented mechanisms for aqueous-phase formation of isoprene SOA (Fu et al., 2008, 2009; Carlton et al., 2008; Myriokefalitakis et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Pye et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Yields of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) from isoprene oxidation as reported by chamber studies in the literature and plotted as a function of the initial NO concentration and relative humidity (RH). Yields are defined as the mass of SOA produced per unit mass of isoprene oxidized. For studies with no detectable NO we plot the NO concentration as half the reported instrument detection limit, and stagger points as needed for clarity. Data are colored by relative humidity (RH). The thick grey line divides the low-NOx and high-NOx pathways as determined by the fate of the ISOPO2 radical (HO2 dominant for the low-NOx pathway, NO dominant for the high-NOx pathway). The transition between the two pathways occurs at a higher NO concentration than in the atmosphere because HO2 concentrations in the chambers are usually much higher. Also shown as dashed line is the mean atmospheric yield of 3.3% for the Southeast US determined in our study.

Here we present a mechanism for irreversible aqueous-phase isoprene SOA formation integrated within a detailed chemical mechanism for isoprene gas-phase oxidation, thus linking isoprene SOA formation to gas-phase chemistry and avoiding more generic volatility-based parameterizations that assume dry organic aerosol (Odum et al., 1996; Donahue et al., 2006). We use this mechanism in the GEOS-Chem CTM to simulate observations from the SOAS (surface) and SEAC4RS (aircraft) field campaigns over the Southeast US in summer 2013, with focus on isoprene SOA components and on the relationship between OA and formaldehyde (HCHO). HCHO is a high-yield oxidation product of isoprene (Palmer et al., 2003) and we use the OA-HCHO relationship as a constraint on isoprene SOA yields. SOAS measurements were made at a ground site in rural Centreville, Alabama (Hu et al., 2015; http://soas2013.rutgers.edu/). SEAC4RS measurements were made from the NASA DC-8 aircraft with extensive boundary layer coverage across the Southeast (Toon et al., 2016; SEAC4RS Archive).

2. Chemical mechanism for isoprene SOA formation

The default treatment of isoprene SOA in GEOS-Chem at the time of this work (v9–02; http://geos-chem.org) followed a standard parameterization operating independently from the gas-phase chemistry mechanism and based on reversible partitioning onto pre-existing OA of generic semivolatile products of isoprene oxidation by OH and NO3 radicals (Pye et al., 2010). Here we implement a new mechanism for reactive uptake by aqueous aerosols of species produced in the isoprene oxidation cascade of the GEOS-Chem gas-phase mechanism. This couples SOA formation to the gas-phase chemistry and is in accord with increased evidence for a major role of aqueous aerosols in isoprene SOA formation (Ervens et al., 2011).

The standard gas-phase isoprene oxidation mechanism in GEOS-Chem v9–02 is described in Mao et al. (2013) and is based on best knowledge at the time building on mechanisms for the oxidation of isoprene by OH (Paulot et al., 2009a; 2009b) and NO3 (Rollins et al., 2009). Updates implemented in this work are described below and in companion papers applying GEOS-Chem to simulation of observed gas-phase isoprene oxidation products over the Southeast US in summer 2013 (Fisher et al., 2016; Travis et al., 2016). Most gas-phase products of the isoprene oxidation cascade in GEOS-Chem have high dry deposition velocity, competing in some cases with removal by oxidation and aerosol formation (Nguyen et al., 2015a; Travis et al., 2016).

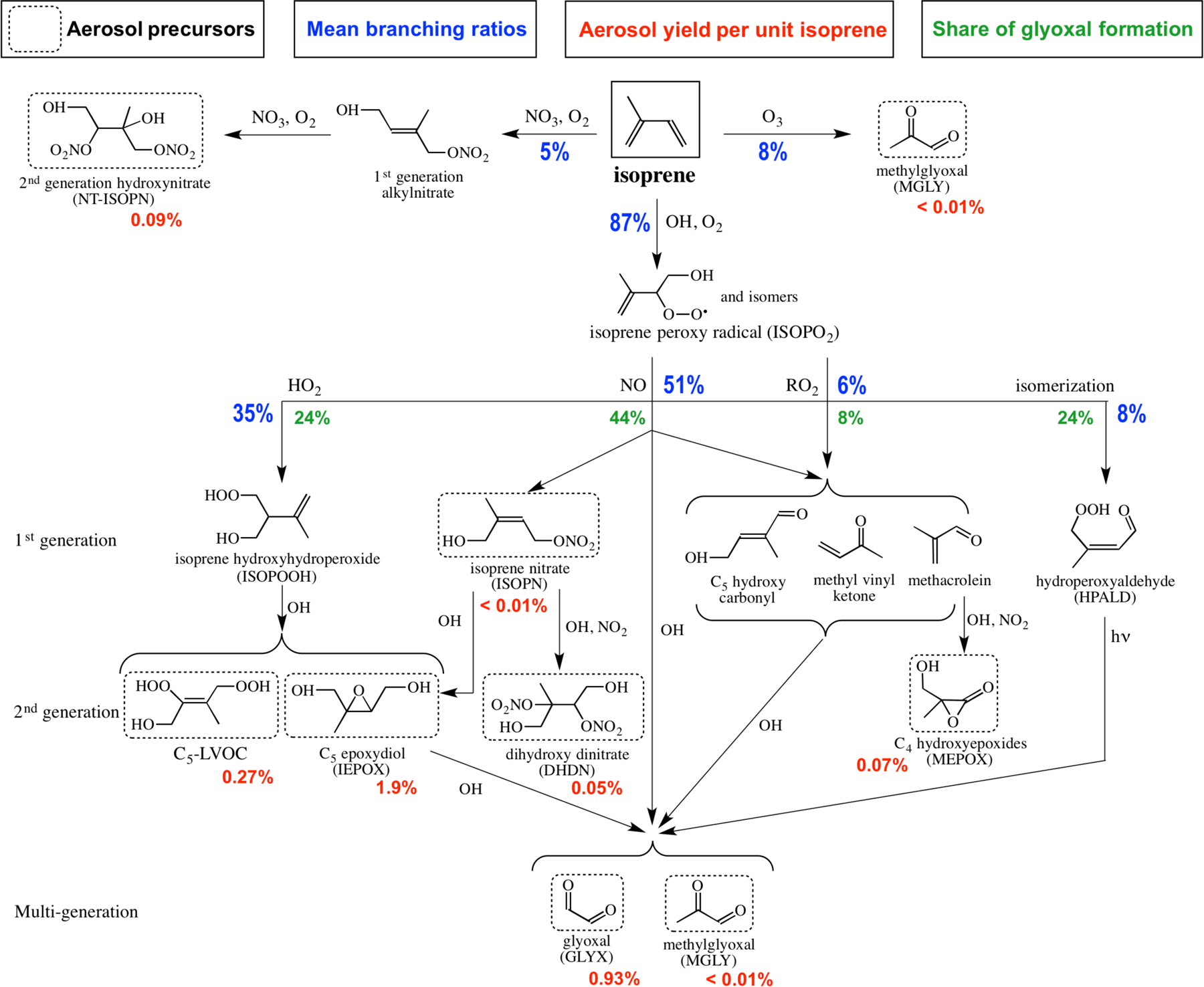

Figure 2 shows the isoprene oxidation cascade in GEOS-Chem leading to SOA formation. Reaction pathways leading to isoprene SOA precursors are described below. Yields are in mass percent, unless stated otherwise. Reactive ISOPO2 isomers formed in the first OH oxidation step react with NO, the hydroperoxyl radical (HO2), other peroxy radicals (RO2), or undergo isomerization (Peeters et al., 2009). The NO reaction pathway (high-NOx pathway) yields C5 hydroxy carbonyls, methyl vinyl ketone, methacrolein, and first-generation isoprene nitrates (ISOPN). The first three products go on to produce glyoxal and methylglyoxal, which serve as SOA precursors. The overall yield of glyoxal from the high-NOx pathway is 7 mol % (yield on a molar basis). Oxidation of ISOPN by OH and O3 is as described by Lee et al. (2014). Reaction of ISOPN with OH produces saturated dihydroxy dinitrates (DHDN), 21 and 27 mol % from the beta and delta channels respectively (Lee et al., 2014), and 10 mol % isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX) from each channel (Jacobs et al., 2014). We also adopt the mechanism of Lin et al. (2013) to generate C4 hydroxyepoxides (methacrylic acid epoxide and hydroxymethylmethyl-α-lactone, both denoted MEPOX) from OH oxidation of a peroxyacylnitrate formed when methacrolein reacts with OH followed by NO2. Only hydroxymethylmethyl-α-lactone is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Gas-phase isoprene oxidation cascade in GEOS-Chem leading to secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation by irreversible aqueous-phase chemistry. Only selected species relevant to SOA formation are shown. Immediate aerosol precursors are indicated by dashed boxes. Branching ratios and SOA yields (aerosol mass produced per unit mass isoprene reacted) are mean values from our GEOS-Chem simulation for the Southeast US boundary layer in summer. The total SOA yield from isoprene oxidation is 3.3% and the values shown below the dashed boxes indicate the contributions from the different immediate precursors adding up to 3.3%. Contributions of high- and low-NOx isoprene oxidation pathways to glyoxal are indicated.

The HO2 reaction pathway for ISOPO2 leads to formation of hydroxyhydroperoxides (ISOPOOH) that are oxidized to IEPOX (Paulot et al., 2009b) and several low-volatility products, represented here as C5-LVOC (Krechmer et al., 2015). The kinetics of IEPOX oxidation by OH is uncertain, and experimentally determined IEPOX lifetimes vary from 8 to 28 h for an OH concentration of 1 × 106 molecules cm−3 (Jacobs et al., 2013; Bates et al., 2014). In GEOS-Chem we apply the fast kinetics of Jacobs et al. (2013) and reduce the yield of IEPOX from ISOPOOH from 100 to 75%, within the range observed by St. Clair et al. (2016), to address a factor of 4 overestimate in simulated IEPOX pointed out by Nguyen et al. (2015a). The IEPOX discrepancy could alternatively be addressed with an order-of-magnitude increase in uptake by aerosol (see below) but the model would then greatly overestimate the observed IEPOX SOA concentrations in SOAS and SEAC4RS (Section 4).

IEPOX oxidizes to form glyoxal and methylglyoxal (Bates et al., 2014). The overall glyoxal yield from the ISOPO2 + HO2 pathway is 6 mol %. Krechmer et al. (2015) report a 2.5 mol % yield of C5-LVOC from ISOPOOH but we reduce this to 0.5 mol % to reproduce surface observations of the corresponding aerosol products (Section 4). Methyl vinyl ketone and methacrolein yields from the ISOPO2 + HO2 pathway are 2.5 and 3.8 mol %, respectively (Liu et al., 2013), sufficiently low that they do not lead to significant SOA formation.

Minor channels for ISOPO2 are isomerization and reaction with RO2. Isomerization forms hydroperoxyaldehydes (HPALD) that go on to photolyze, but products are uncertain (Peeters and Müller, 2010). We assume 25 mol % yield each of glyoxal and methylglyoxal from HPALD photolysis in GEOS-Chem following Stavrakou et al. (2010). Reaction of ISOPO2 with RO2 leads to the same suite of C4–C5 carbonyls as reaction with NO (C5 hydroxy carbonyls, methacrolein, and methyl vinyl ketone) and from there to glyoxal and methylglyoxal.

Immediate aerosol precursors from the isoprene + OH oxidation cascade are identified in Fig. 2. For the high-NOx pathway (ISOPO2 + NO channel) these include glyoxal and methylglyoxal (McNeill et al., 2012), ISOPN (Darer et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011), DHDN (Lee et al., 2014), MEPOX (Lin et al., 2013), and IEPOX (Jacobs et al., 2014). For the low-NOx pathway (ISOPO2 + HO2 channel) aerosol precursors are IEPOX (Eddingsaas et al., 2010), C5-LVOC (Krechmer et al., 2015, in which the aerosol-phase species is denoted ISOPOOH-SOA), glyoxal, and methylglyoxal. Glyoxal and methylglyoxal are also produced from the ISOPO2 + RO2 and ISOPO2 isomerization channels.

Ozonolysis and oxidation by NO3 are additional minor isoprene reaction pathways (Fig. 2). The NO3 oxidation pathway is a potentially important source of isoprene SOA at night (Brown et al., 2009) from the irreversible uptake of low-volatility second-generation hydroxynitrates (NT-ISOPN) (Ng et al., 2008; Rollins et al., 2009). We update the gas-phase chemistry of Rollins et al. (2009) as implemented by Mao et al. (2013) to include formation of 4 mol % of the aerosol-phase precursor NT-ISOPN from first-generation alkylnitrates (Rollins et al., 2009). Ozonolysis products are volatile and observed SOA yields in chamber studies are low (< 1%; Kleindienst et al., 2007). In GEOS-Chem only methylglyoxal is an aerosol precursor from isoprene ozonolysis.

We implement uptake of isoprene oxidation products to aqueous aerosols using laboratory-derived reactive uptake coefficients (γ) as given by Anttila et al. (2006) and Gaston et al. (2014):

| (1) |

Here α is the mass accommodation coefficient (taken as 0.1 for all immediate SOA precursors in Fig. 2), ω is the mean gas-phase molecular speed (cm s−1), r is the aqueous particle radius (cm), R is the universal gas constant (0.08206 L atm K−1 mol−1), T is temperature (K), H* is the effective Henry’s Law constant (M atm−1) accounting for any fast dissociation equilibria in the aqueous phase, and kaq is the pseudo first-order aqueous-phase reaction rate constant (s−1) for conversion to non-volatile products.

Precursors with epoxide functionality, IEPOX and MEPOX, undergo acid-catalyzed epoxide ring opening and nucleophilic addition in the aqueous phase. The aqueous-phase rate constant formulation is from Eddingsaas et al. (2010),

| (2) |

and includes three channels: acid-catalyzed ring opening followed by nucleophilic addition of leading to methyltetrols, acid-catalyzed ring opening followed by nucleophilic addition of sulfate and nitrate ions (nuc ≡ SO42− + NO3−, knuc in M−2 s−1) leading to organosulfates and organonitrates, and concerted protonation and nucleophilic addition by bisulfate, HSO4− (kHSO4− in M−1 s−1), leading to organosulfates.

Precursors with nitrate functionality (−ONO2), ISOPN and DHDN, hydrolyze to form low-volatility polyols and nitric acid (Hu et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2014), so kaq in Eq. (1) is the hydrolysis rate constant.

Glyoxal and methylglyoxal form SOA irreversibly by surface uptake followed by aqueous-phase oxidation and oligomerization to yield non-volatile products (Liggio et al., 2005; Volkamer et al., 2009; Nozière et al., 2009; Ervens et al., 2011; Knote et al., 2014). Glyoxal forms SOA with higher yields during the day than at night due to OH aqueous-phase chemistry (Tan et al., 2009; Volkamer et al., 2009; Summer et al., 2014). We use a daytime γ of 2.9 × 10−3 for glyoxal from Liggio et al. (2005) and a nighttime γ of 5 × 10−6 (Waxman et al., 2013; Sumner et al., 2014). The SOA yield of methylglyoxal is small compared with that of glyoxal (McNeill et al., 2012). A previous GEOS-Chem study by Fu et al. (2008) used the same γ (2.9 × 10−3) for glyoxal and methylglyoxal. Reaction rate constants are similar for aqueous-phase processing of glyoxal and methylglyoxal (Buxton et al., 1997; Ervens et al., 2003), but H* of glyoxal is about 4 orders of magnitude higher. Here we scale the γ for methylglyoxal to the ratio of effective Henry’s law constants: H* = 3.7 × 103 M atm−1 for methylglyoxal (Tan et al., 2010) and H* = 2.7 × 107 M atm−1 for glyoxal (Sumner et al., 2014). The resulting uptake of methylglyoxal is very slow and makes a negligible contribution to isoprene SOA.

The species C5-LVOC from ISOPOOH oxidation and NT-ISOPN from isoprene reaction with NO3 have very low volatility and are assumed to condense to aerosols with a γ of 0.1 limited by mass accommodation. Results are insensitive to the precise value of γ since uptake by aerosols is the main sink for these species in any case.

Table 1 gives input variables used to calculate γ for IEPOX, ISOPN, and DHDN by Eqs. (1) and (2). Rate constants are from experiments in concentrated media, representative of aqueous aerosols, so no activity correction factors are applied. Reported experimental values of kH+ vary by an order of magnitude from 1.2 × 10−3 M−1 s−1 (Eddingsaas et al., 2010) to 3.6 × 10−2 M−1 s−1 (Cole-Filipiak et al., 2010). Values of knuc vary by 3 orders of magnitude from 2 × 10−4 M−2 s−1 (Eddingsaas et al., 2010) to 5.2 × 10−1 M−2 s−1 (Piletic et al., 2013). Reported values of IEPOX H* vary by two orders of magnitude (Eddingsaas et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2014). We chose values of kH+, knuc, and H* to fit the SOAS and SEAC4RS observations of total IEPOX SOA and IEPOX organosulfates, as discussed in Section 4.

Table 1.

Constants for reactive uptake of isoprene SOA precursorsa

| Speciesb | H* [M atm−1] | kH+ [M−1 s−1] | knuc [M−2 s−1] | kHSO4- [M−1 s−1] | kaq [s−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEPOX | 3.3 × 107, c | 3.6 × 10−2, d | 2.0 × 10−4, e | 2.0 × 10−4, e | Equation (2) |

| ISOPNβf | 3.3 × 105, g | - | - | - | 1.6 × 10−5, h |

| ISOPNδf | 3.3 × 105, g | - | - | - | 6.8 × 10−3, h |

| DHDN | 3.3 × 105, g | - | - | - | 6.8 × 10−3, i |

Effective Henry’s law constants H* and aqueous-phase rate constants used to calculate reactive uptake coefficients γ for isoprene SOA precursors IEPOX, ISOPNβ, ISOPNδ, and DHDN following Eqs. (1) and (2). Calculation of γ for other isoprene SOA precursors in Fig. 2 is described in the text.

See Fig. 2 for definition of acronyms.

Best fit to SOAS and SEAC4RS IEPOX SOA and consistent with Nguyen et al. (2014).

ISOPN species formed from the beta and delta isoprene oxidation channels (Paulot et al., 2009a) are treated separately in GEOS-Chem.

By analogy with 4-nitrooxy-3-methyl-2-butanol (Rollins et al., 2009).

Assumed same as for ISOPNδ (Hu et al., 2011).

Table 2 lists average values of γ for all immediate aerosol precursors in the Southeast US boundary layer in summer as simulated by GEOS-Chem (Section 3). γ for IEPOX is a strong function of pH and increases from 1 × 10−4 to 1 × 10−2 as pH decreases from 3 to 0. Gaston et al. (2014) reported order-of-magnitude higher values of γ for IEPOX, reflecting their use of a higher H*, but this would lead in our model to an overestimate of IEPOX SOA observations (Section 4). The value of γ for MEPOX is assumed to be 30 times lower than that of IEPOX when the aerosol is acidic (pH < 4), due to slower acid-catalyzed ring opening (Piletic et al., 2013; Riedel et al., 2015). At pH > 4 we assume that γ for IEPOX and MEPOX are the same (Riedel et al., 2015), but they are then very low.

Table 2.

Mean reactive uptake coefficients γ of isoprene SOA precursorsa

| Speciesb | γ | pH dependencec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH > 3 | 2 < pH < 3 | 1< pH < 2 | 0 < pH < 1 | ||

| IEPOX | 4.2 × 10−3 | 8.6 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−2 |

| MEPOX | 1.3 × 10−4 | 2.7 × 10−8 | 6.4 × 10−6 | 3.6 × 10−5 | 3.2 × 10−4 |

| ISOPNβ | 1.3 × 10−7 | - | |||

| ISOPNδ | 5.2 × 10−5 | - | |||

| DHDN | 6.5 × 10−5 | - | |||

| GLYX | 2.9 × 10−3, d | - | |||

| MGLY | 4.0 × 10−7 | - | |||

| C5-LVOC | 0.1 | - | |||

| NT-ISOPN | 0.1 | - | |||

Mean values computed in GEOS-Chem for the Southeast US in summer as sampled along the boundary-layer (< 2 km) SEAC4RS aircraft tracks and applied to aqueous aerosol. The reactive uptake coefficient γ is defined as the probability that a gas molecule colliding with an aqueous aerosol particle will be taken up and react in the aqueous phase to form non-volatile products.

See Fig. 2 for definition of acronyms.

γ for IEPOX and MEPOX are continuous functions of pH (Eq. (2)). Values shown here are averages for different pH ranges sampled along the SEAC4RS flight tracks. Aqueous aerosol pH is calculated locally in GEOS-Chem using the ISORROPIA thermodynamic model (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007).

Daytime value. Nighttime value is 5 × 10−6.

Isoprene SOA formation in clouds is not considered here. Acid-catalyzed pathways would be slow. Observations show that the isoprene SOA yield in the presence of laboratory-generated clouds is low (0.2–0.4%; Brégonzio-Rozier et al., 2015). Wagner et al. (2015) found no significant production of SOA in boundary layer clouds over the Southeast US during SEAC4RS.

3. GEOS-Chem simulation and isoprene SOA yields

Several companion papers apply GEOS-Chem to interpret SEAC4RS and surface data over the Southeast US in summer 2013 including Kim et al. (2015) for aerosols, Fisher et al. (2016) for organic nitrates, Travis et al. (2016) for ozone and NOx, and Zhu et al. (2016) for HCHO. These studies use a model version with 0.25° × 0.3125° horizontal resolution over North America, nested within a 4° × 5° global simulation. Here we use a 2° × 2.5° global GEOS-Chem simulation with no nesting. Yu et al. (2016) found little difference between 0.25° × 0.3125° and 2° × 2.5° resolutions in simulated regional statistics for isoprene chemistry.

The reader is referred to Kim et al. (2015) for a general presentation of the model, the treatment of aerosol sources and sinks, and evaluation with Southeast US aerosol observations; and to Travis et al. (2016) and Fisher et al. (2016) for presentation of gas-phase chemistry and comparisons with observed gas-phase isoprene oxidation products. Isoprene emission is from the MEGAN v2.1 inventory (Guenther et al., 2012). The companion papers decrease isoprene emission by 15% from the MEGAN v2.1 values to fit the HCHO data (Zhu et al., 2016), but this is not applied here.

Our SOA simulation differs from that of Kim et al. (2015). They assumed fixed 3% and 10% mass yields of SOA from isoprene and monoterpenes, respectively, and parameterized SOA formation from anthropogenic and open fire sources as a kinetic irreversible process following Hodzic and Jimenez (2011). Here we use our new aqueous-phase mechanism for isoprene SOA coupled to gas-phase chemistry as described in Section 2, and otherwise use the semivolatile reversible partitioning scheme of Pye et al. (2010) for monoterpene, anthropogenic, and open fire SOA. Kim et al. (2015) found no systematic bias in detailed comparisons to OA measurements from SEAC4RS and from surface networks. We find a low bias, as shown below, because the reversible partitioning scheme yields low anthropogenic and open fire SOA concentrations.

Organic aerosol and sulfate contribute most of the aerosol mass over the Southeast US in summer, while nitrate is negligibly small (Kim et al., 2015). GEOS-Chem uses the ISORROPIA thermodynamic model (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007) to simulate sulfate-nitrate-ammonium (SNA) aerosol composition, water content, and acidity as a function of local conditions. Simulated aerosol pH along the SEAC4RS flight tracks in the Southeast US boundary layer averages 1.3 (interquartiles 0.92 and 1.8). The aerosol pH remains below 3 even when sulfate aerosol is fully neutralized by ammonia (Guo et al., 2015).

We consider that the aqueous aerosol population where isoprene SOA formation can take place is defined by the sulfate aerosol population. This assumes that all aqueous aerosol particles contain some sulfate, and that all sulfate is aqueous. Clear-sky RH measured from the aircraft in the Southeast US boundary layer during SEAC4RS averaged 72 ± 17%, and the corresponding values in GEOS-Chem sampled along the flight tracks averaged 66 ± 16%). These RHs are sufficiently high that sulfate aerosol can reliably be expected to be aqueous (Wang et al., 2008). The rate of gas uptake by the sulfate aerosol is computed with the pseudo-first order reaction rate constant khet (s−1) (Schwartz, 1986; Jacob, 2000):

| (3) |

where Dg is the gas-phase diffusion constant (taken to be 0.1 cm2 s−1) and n(r) is the number size distribution of sulfate aerosol (cm−4). The first and second terms in parentheses describe the limitations to gas uptake from gas-phase diffusion and aqueous-phase reaction, respectively.

The sulfate aerosol size distribution including RH-dependent hygroscopic growth factors is from the Global Aerosol Data Set (GADS) of Koepke et al. (1997), as originally implemented in GEOS-Chem by Martin et al. (2003) and updated by Drury et al. (2010). The GADS size distribution compares well with observations over the eastern US in summer (Drury et al., 2010), including for SEAC4RS (Kim et al., 2015). We compute n(r) locally in GEOS-Chem by taking the dry SNA mass concentration, converting from mass to volume with a dry aerosol mass density of 1700 kg m−3 (Hess et al., 1998), applying the aerosol volume to the dry sulfate size distribution in GADS, and then applying the GADS hygroscopic growth factors. We verified that the hygroscopic growth factors from GADS agree within 10% with those computed locally from ISORROPIA.

Figure 2 shows the mean branching ratios for isoprene oxidation in the Southeast US boundary layer as calculated by GEOS-Chem. 87% of isoprene reacts with OH, 8% with ozone, and 5% with NO3. Oxidation of isoprene by OH produces ISOPO2 of which 51% reacts with NO (high-NOx pathway), 35% reacts with HO2, 8% isomerizes, and 6% reacts with other RO2 radicals.

Glyoxal is an aerosol precursor common to all isoprene + OH pathways in our mechanism with yields of 7 mol % from the ISOPO2 + NO pathway, 6 mol % from ISOPO2 + HO2, 11 mol % from ISOPO2 + RO2, and 25 mol % from ISOPO2 isomerization. For the Southeast US conditions we thus find that 44% of glyoxal is from the ISOPO2 + NO pathway, 24% from ISOPO2 + HO2, 8% from ISOPO2 + RO2, and 24% from ISOPO2 isomerization.

The mean total yield of isoprene SOA computed in GEOS-Chem for the Southeast US boundary layer is 3.3%, as shown in Fig. 2. IEPOX contributes 1.9% and glyoxal 0.9%. The low-NOx pathway involving ISOPO2 reaction with HO2 contributes 73% of the total isoprene SOA yield, mostly from IEPOX, even though this pathway is only 35% of the fate of ISOPO2. The high-NOx pathway contributes 16% of isoprene SOA, mostly from glyoxal. MEPOX contribution to isoprene SOA is small (2%) and consistent with a recent laboratory study that finds low SOA yields from this pathway under humid conditions (Nguyen et al., 2015b). The minor low-NOx pathways from ISOPO2 isomerization and reaction with RO2 contribute 8% of isoprene SOA through glyoxal. The remainder of isoprene SOA formation (3%) is from nighttime oxidation by NO3.

The dominance of IEPOX and glyoxal as precursors for isoprene SOA was previously found by McNeill et al. (2012) using a photochemical box model. Both IEPOX and glyoxal are produced photochemically, and both are removed photochemically in the gas phase by reaction with OH (and photolysis for glyoxal). The mean lifetimes of IEPOX and glyoxal against gas-phase photochemical loss average 1.6 and 2.3 h respectively for SEAC4RS daytime conditions; mean lifetimes against reactive uptake by aerosol are 31 and 20 hours, respectively. For both species, aerosol uptake is thus a minor sink competing with gas-phase photochemical loss. Although we have assumed here the fast gas-phase kinetics from Jacobs et al. (2013) for the IEPOX + OH reaction, this result would not change if we used the slower kinetics from Bates et al. (2014).

The dominance of gas-phase loss over aerosol uptake for both IEPOX and glyoxal implies that isoprene SOA formation is highly sensitive to their reactive uptake coefficients γ and to the aqueous aerosol mass concentration (in both cases, γ is small enough that uptake is controlled by bulk aqueous-phase rather than surface reactions). We find under SEAC4RS conditions that γ for IEPOX is mainly controlled by the H+ concentration (kH+[H+] in Eq. (2)), with little contribution from nucleophile-driven and HSO4−-driven channels, although this is based on highly uncertain rate constants (Section 2). Consistency with SOAS and SEAC4RS observations will be discussed below.

The 3.3% mean yield of isoprene SOA from our mechanism is consistent with the fixed yield of 3% assumed by Kim et al. (2015) in their GEOS-Chem simulation of the SEAC4RS period, including extensive comparisons to OA observations that showed a 40% mean contribution of isoprene to total OA. We conducted a sensitivity simulation using the default isoprene SOA mechanism in GEOS-Chem based on reversible partitioning of semivolatile oxidation products onto pre-existing OA (Pye et al., 2010). The isoprene SOA yield in that simulation was only 1.1%. The observed correlation of OA with HCHO in SEAC4RS supports our higher yield, as shown below.

4. Observational constraints on isoprene SOA yields

Isoprene is the largest source of HCHO in the Southeast US (Millet et al., 2006), and we use the observed relationship between OA and HCHO to evaluate the GEOS-Chem isoprene SOA yields. The SEAC4RS aircraft payload included measurements of OA from an Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS; DeCarlo et al, 2006; Canagaratna et al, 2007) concurrent with HCHO from a laser-induced fluorescence instrument (ISAF; Cazorla et al., 2015). Column HCHO was also measured during SEAC4RS from the OMI satellite instrument (González Abad et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016), providing a proxy for isoprene emission (Palmer et al., 2003; 2006).

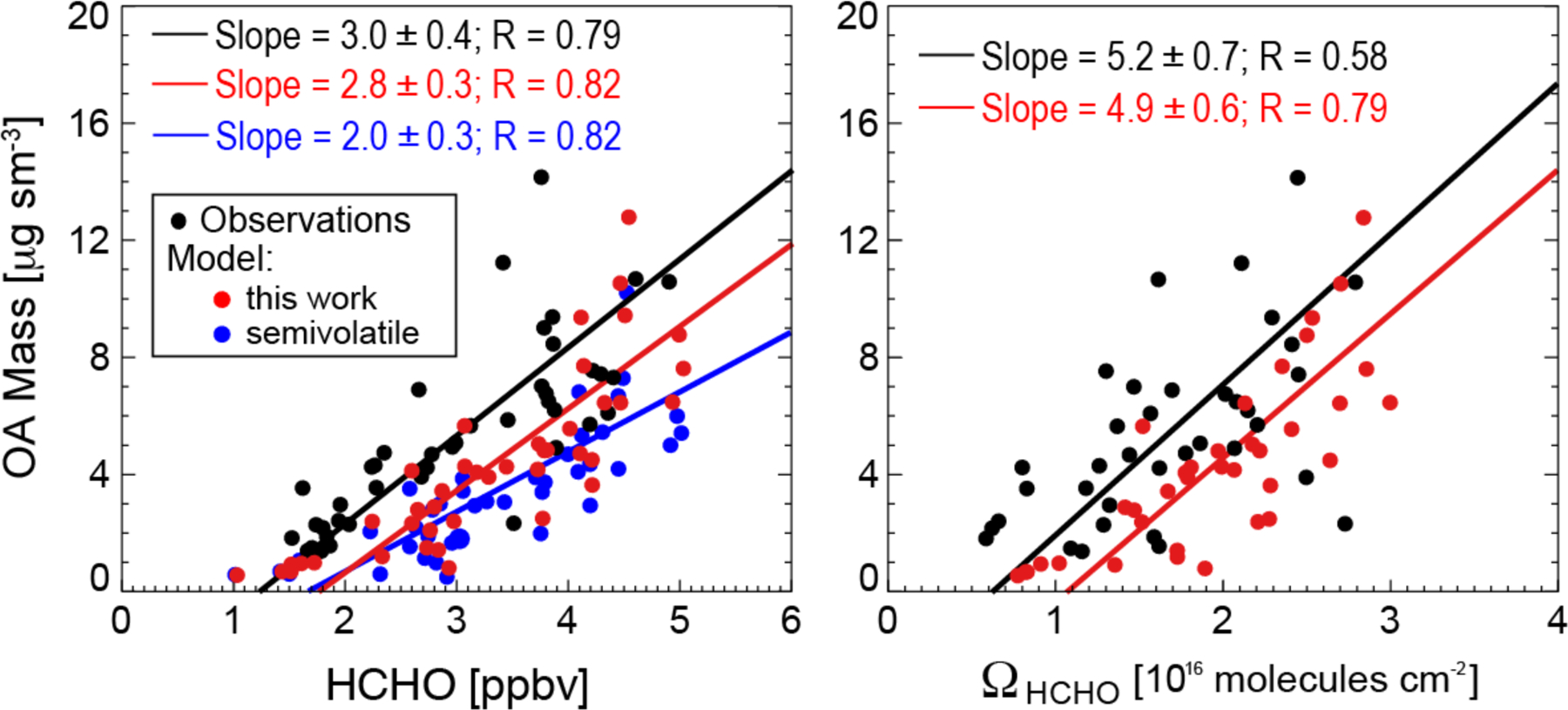

Figure 3 (left) shows the observed and simulated relationships between OA and HCHO mixing ratios in the boundary layer. There is a strong correlation in the observations and in the model (R = 0.79 and R = 0.82, respectively). OA simulated with our aqueous-phase isoprene SOA mechanism reproduces the observed slope (2.8 ± 0.3 μg sm−3 ppbv−1, vs. 3.0 ± 0.4 μg sm−3 ppbv−1 in the observations). Similarly strong correlations and consistency between model and observations are found with column HCHO measured from OMI (Fig. 3, right). The estimated error on individual OMI HCHO observations is about 30% (Millet et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

Relationship of organic aerosol (OA) and formaldehyde (HCHO) concentrations over the Southeast US in summer. The figure shows scatterplots of SEAC4RS aircraft observations of OA concentrations in the boundary layer (< 2 km) vs. HCHO mixing ratios measured from the aircraft (left), and column HCHO (ΩHCHO) retrieved from OMI satellite observations (right). Individual points are data from individual SEAC4RS flight days (August 8 – September 10), averaged on the GEOS-Chem grid. OMI data are for SEAC4RS flight days and coincident with the flight tracks. GEOS-Chem is sampled for the corresponding locations and times. Results from our simulation with aqueous-phase isoprene SOA chemistry are shown in red, and results from a simulation with the Pye et al. (2010) semivolatile reversible partitioning scheme are shown in blue. Aerosol concentrations are per m3 at standard conditions of temperature and pressure (STP: 273 K; 1 atm), denoted sm−3. Reduced major axis (RMA) regressions are also shown with regression parameters and Pearson’s correlation coefficients given inset. 1σ standard deviations on the regression slopes are obtained with jackknife resampling.

Also shown in Fig. 3 is a sensitivity simulation with the default GEOS-Chem mechanism based on reversible partitioning with pre-existing organic aerosol (Pye et al., 2010) and producing a 1.1% mean isoprene SOA yield, as compared to 3.3% in our simulation with the aqueous-phase mechanism. That sensitivity simulation shows the same OA-HCHO correlation (R = 0.82) but underestimates the slope (2.0 ± 0.3 μg sm−3 ppbv−1). The factor of 3 increase in our isoprene SOA yield does not induce a proportional increase in the slope, as isoprene contributes only ~ 40% of OA in the Southeast US. But the slope is sensitive to the isoprene SOA yield, and the good agreement between our simulation and observations supports our estimate of a mean 3.3% yield for the Southeast US.

Figure 3 shows an offset between the model and observations illustrated by the regression lines. We overestimate HCHO by 0.4 ppbv on average because we did not apply the 15% downward correction to MEGAN v2.1 isoprene emissions (Zhu et al., 2016). We also underestimate total OA measured by the AMS in the boundary layer by 1.1 μg sm−3 (mean AMS OA is 5.8 ± 4.3 μg sm−3; model OA is 4.7 ± 4.4 μg sm−3). The bias can be explained by our omission of anthropogenic and open fire SOA, found by Kim et al. (2015) to account on average for 18% of OA in SEAC4RS.

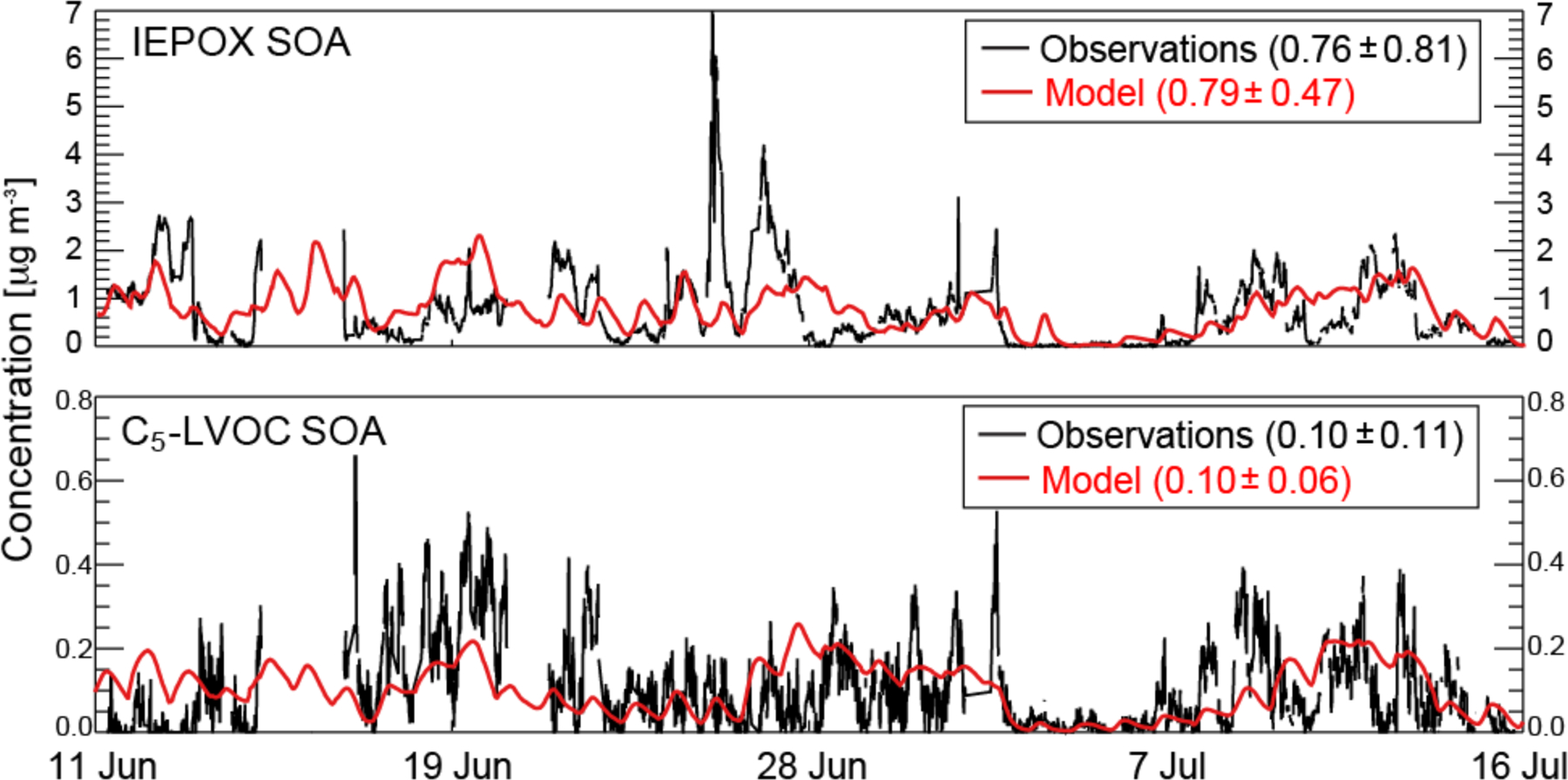

Figure 4 shows time series of the isoprene SOA components IEPOX SOA and C5-LVOC SOA at Centreville, Alabama during SOAS. AMS observations from Hu et al. (2015) and Krechmer et al. (2015) are compared to model values. IEPOX SOA and C5-LVOC SOA are on average 17% and 2% of total AMS OA, respectively (Hu et al., 2015; Krechmer et al., 2015). The model reproduces mean IEPOX SOA and C5-LVOC SOA without bias, supporting the conclusion that IEPOX is the dominant contributor to isoprene SOA in the Southeast US (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Time series of the concentrations of isoprene SOA components at the SOAS site in Centreville, Alabama (32.94°N; 87.18°W) in June–July 2013: measured (black) and modeled (red) IEPOX SOA (top) and C5-LVOC SOA (bottom) mass concentrations. Means and 1σ standard deviations are given for the observations and the model.

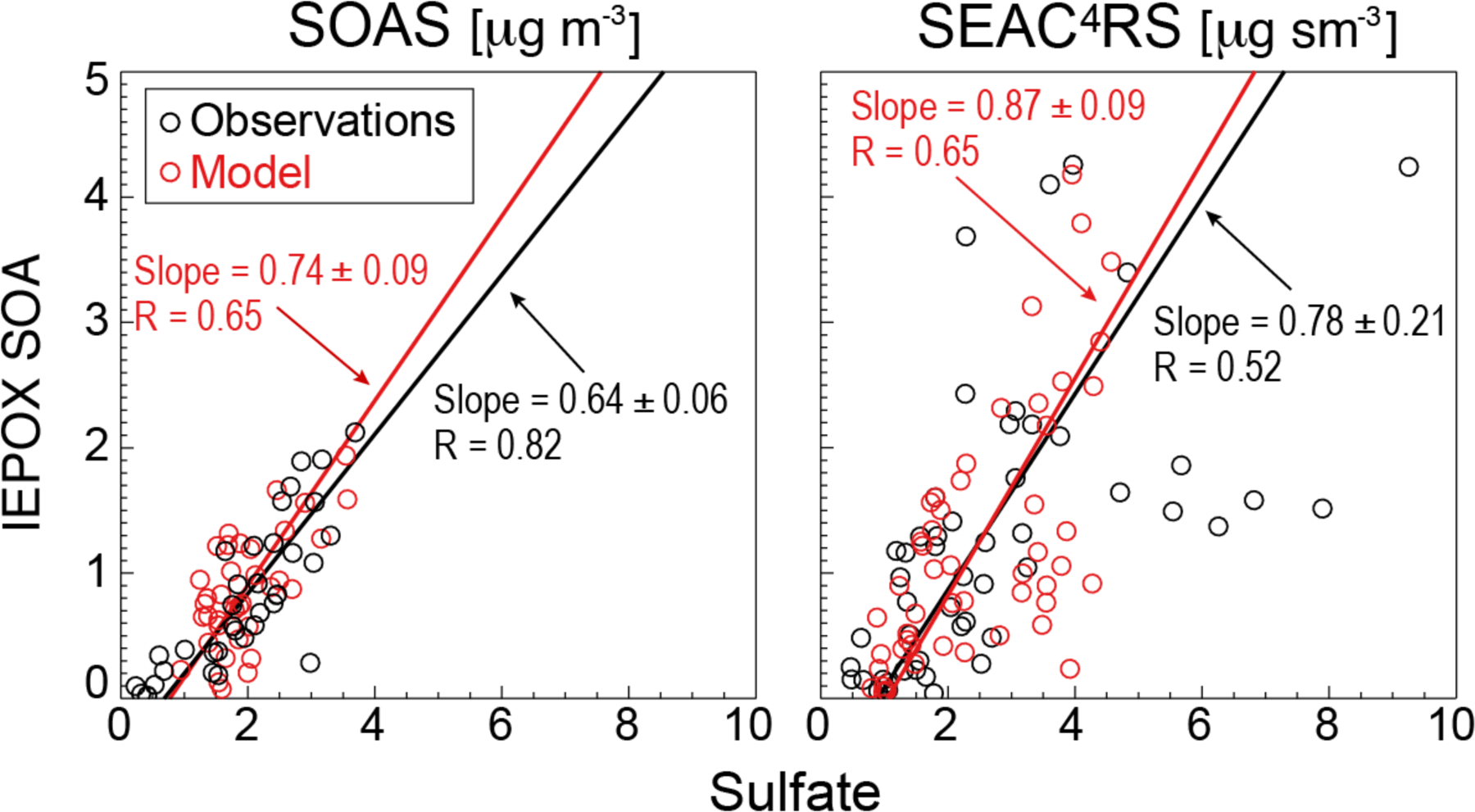

Figure 5 shows the relationships of daily mean IEPOX SOA and sulfate concentrations at Centreville and in the SEAC4RS boundary layer. The same factor analysis method was used to derive IEPOX SOA in SEAC4RS as in SOAS, however the uncertainty is larger for the aircraft observations due to the much wider range of conditions encountered. There is a strong correlation between IEPOX SOA and sulfate, both in observations and the model, with similar slopes. Correlation between IEPOX SOA and sulfate has similarly been observed at numerous Southeast US monitoring sites (Budisulistiorini et al., 2013; 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2015). Xu et al. (2015) concluded that IEPOX SOA may form by nucleophilic addition of sulfate (sulfate channels in Eq. (2)) leading to organosulfates. However, we find in our model that the H+-catalyzed channel (kH+[H+] term in Eq. (2)) contributes 90% of IEPOX SOA formation throughout the Southeast US boundary layer, and that sulfate channels play only a minor role. The correlation of IEPOX SOA and sulfate in the model is because increasing sulfate drives an increase in aqueous aerosol volume and acidity. Although dominance of the H+-catalyzed channel is sensitive to uncertainties in the rate constants (Section 2), measurements from the PALMS laser mass spectrometer during SEAC4RS (Liao et al., 2015) show a mean IEPOX organosulfate concentration of 0.13 μg sm−3, amounting to at most 9% of total IEPOX SOA. The organosulfate should be a marker of the sulfate channels because its hydrolysis is negligibly slow (Hu et al., 2011).

Figure 5.

Relationship of IEPOX SOA and sulfate concentrations over the Southeast US in summer. Observed (black) and simulated (red) data are averages for each campaign day during SOAS (left), and boundary layer averages (< 2 km) for 2° × 2.5° GEOS-Chem grid squares on individual flight days during SEAC4RS (right). RMA regression slopes and Pearson’s correlation coefficients are shown. 1σ standard deviations on the regression slopes are obtained with jackknife resampling.

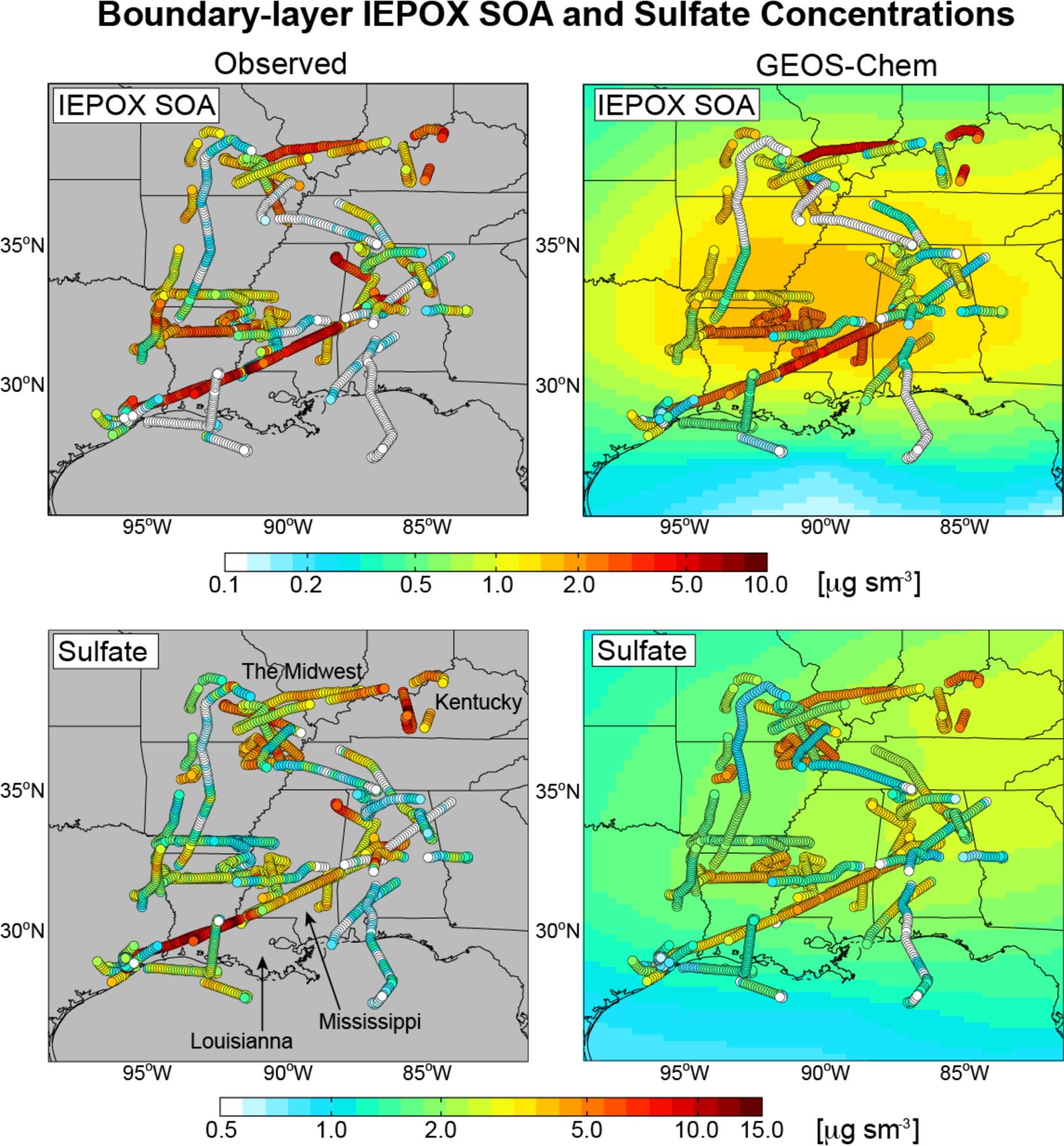

Correlation between IEPOX SOA and sulfate is also apparent in the spatial distribution of IEPOX SOA, as observed by the SEAC4RS aircraft below 2 km and simulated by GEOS-Chem along the aircraft flight tracks (Fig. 6). The correlation between simulated and observed IEPOX SOA in Fig. 6 is R = 0.70. Average (mean) IEPOX SOA is 1.4 ± 1.4 μg sm−3 in the observations and 1.3 ± 1.2 μg sm−3 in the model. The correlation between IEPOX SOA and sulfate is 0.66 in the observations and 0.77 in the model. IEPOX SOA concentrations are highest in the industrial Midwest and Kentucky, and in Louisiana-Mississippi, coincident with the highest sulfate concentrations sampled on the flights. We also see in Fig. 6 frequent observations of very low IEPOX SOA (less than 0.4 μg sm−3) that are well captured by the model. These are associated with very low sulfate (less than 1 μg sm−3).

Figure 6.

Spatial distributions of IEPOX SOA and sulfate concentrations in the boundary layer (<2 km) over the Southeast US during SEAC4RS (August–September 2013). Aircraft AMS observations of IEPOX SOA (top left) and sulfate (bottom left) are compared to model values sampled at the time and location of the aircraft observations (individual points) and averaged during the SEAC4RS period (background contours). Data are on a logarithmic scale.

The mean IEPOX SOA concentration simulated by the model for the SEAC4RS period (background contours in Fig. 6) is far more uniform than IEPOX SOA simulated along the flight tracks. This shows the importance of day-to-day variations in sulfate in driving IEPOX SOA variability. IEPOX SOA contributed on average 24% of total OA in the SEAC4RS observations, and 28% in GEOS-Chem sampled along the flight tracks and as a regional mean. With IEPOX SOA accounting for 58% of isoprene SOA in the model (Fig. 2), this amounts to a 41–48% contribution of isoprene to total OA, consistent with the previous estimate of 40% by Kim et al. (2015).

5. Effect of Anthropogenic Emission Reductions

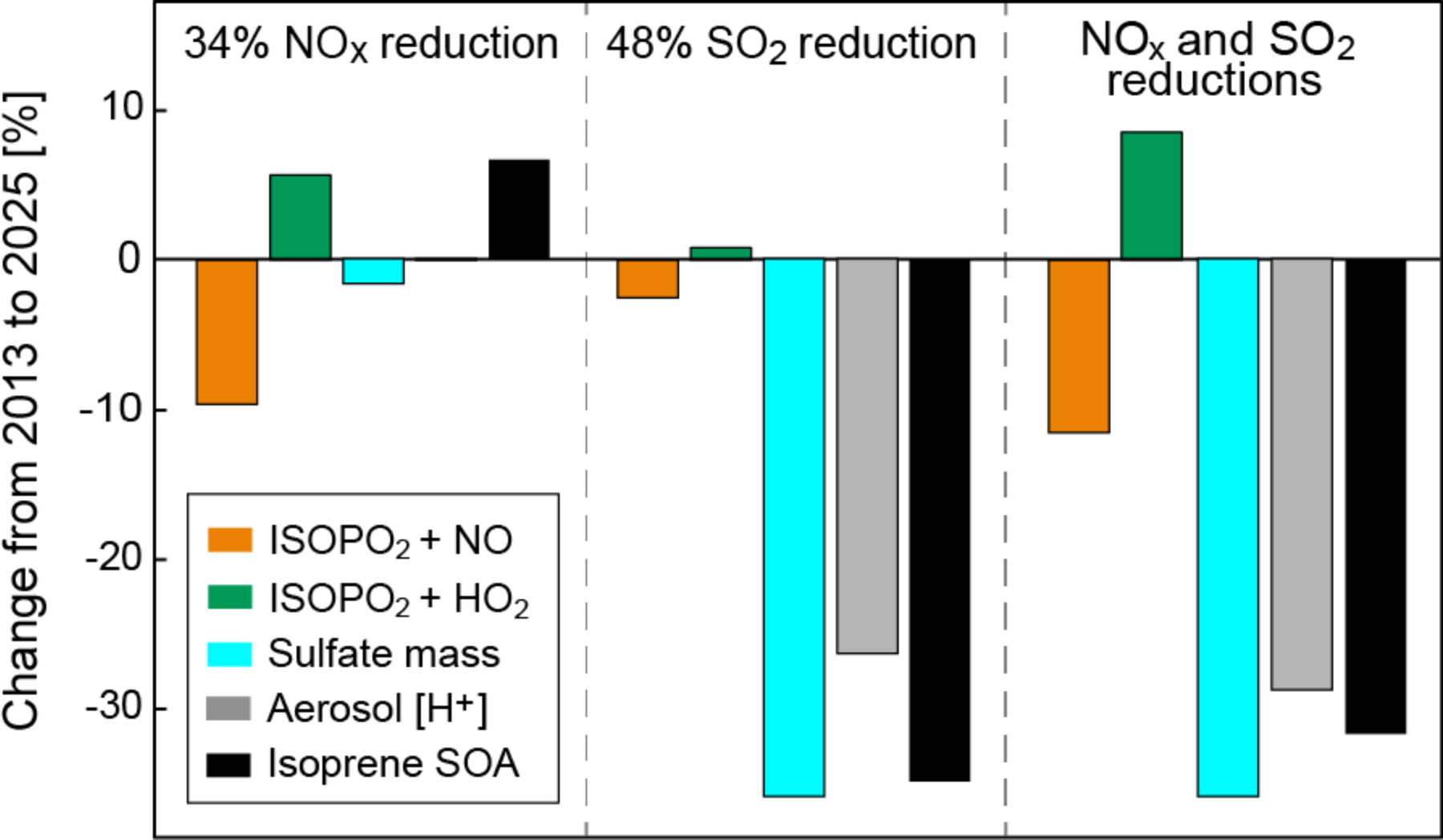

The EPA projects that US anthropogenic emissions of NOx and SO2 will decrease respectively by 34% and 48% from 2013 to 2025 (EPA, 2014). We conducted a GEOS-Chem sensitivity simulation to examine the effect of these changes on isoprene SOA, assuming no other changes and further assuming that the emission decreases are uniform across the US.

Figure 7 shows the individual and combined effects of NOx and SO2 emission reductions on the branching pathways for isoprene oxidation, sulfate mass concentration, aerosol pH, and isoprene SOA in the Southeast US boundary layer in summer. Reducing NOx emission by 34% decreases the mean NO concentration by only 23%, in part because decreasing OH increases the NOx lifetime and in part because decreasing ozone increases the NO/NO2 ratio. There is no change in HO2. We find a 10% decrease in the high-NOx pathway and a 6% increase in the low-NOx pathway involving ISOPO2 + HO2. Aerosol sulfate decreases by 2% and there is no change in [H+]. The net effect is a 7% increase in isoprene SOA, as the major individual components IEPOX SOA and glyoxal SOA increase by 17% and decrease by 8%, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect of projected 2013–2025 reductions in US anthropogenic emissions on the formation of isoprene secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Emissions of NOx and SO2 are projected to decrease by 34% and 48%, respectively. Panels show the resulting percentage changes in the branching of ISOPO2 between the NO and HO2 oxidation channels, sulfate mass concentration, aerosol [H+] concentration, and isoprene SOA mass concentration. Values are summer means for the Southeast US boundary layer.

A 48% decrease in SO2 emissions drives a 36% reduction in sulfate mass concentration, leading to a decline in aerosol volume (31%) that reduces uptake of all isoprene SOA precursors. The decrease in aerosol [H+] (26%) further reduces IEPOX uptake. Decline in aerosol volume and [H+] have a comparable effect on IEPOX SOA, as the change in each due to SO2 emission reductions is similar (~30%) and uptake of IEPOX SOA is proportional to the product of the two (Section 4). IEPOX SOA and glyoxal SOA decrease by 45% and 26%, respectively, and total isoprene SOA decreases by 35%. Pye et al. (2013) included uptake of IEPOX to aqueous aerosols in a regional chemical transport model and similarly found that SO2 emissions are more effective than NOx emissions at reducing IEPOX SOA in the Southeast US. Remarkably, we find that reducing SO2 emissions decreases sulfate and isoprene SOA with similar effectiveness (Fig. 7). With sulfate contributing ~30% of present-day PM2.5 in the Southeast US and isoprene SOA contributing ~25% (Kim et al., 2015), this represents a factor of 2 co-benefit on PM2.5 from reducing SO2 emissions.

6. Conclusions

Standard mechanisms for formation of isoprene secondary organic aerosol (SOA) in chemical transport models assume reversible partitioning of isoprene oxidation products to pre-existing dry OA. This may be appropriate for dry conditions in experimental chambers but not for typical atmospheric conditions where the aerosol is mostly aqueous. Here we developed an aqueous-phase reactive uptake mechanism coupled to a detailed gas-phase isoprene chemistry mechanism to describe the reactive uptake of water-soluble isoprene oxidation products to aqueous aerosol. We applied this mechanism in the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model to simulate surface (SOAS) and aircraft (SEAC4RS) observations over the Southeast US in summer 2013.

Our mechanism includes different channels for isoprene SOA formation by the high-NOx pathway, when the isoprene peroxy radicals (ISOPO2) react with NO, and in the low-NOx pathway where they react mostly with HO2. The main SOA precursors are found to be isoprene epoxide (IEPOX) in the low-NOx pathway and glyoxal in the high- and low-NOx pathways. Both of these precursors have dominant gas-phase photochemical sinks, and so their uptake by aqueous aerosol is nearly proportional to the reactive uptake coefficient γ and to the aqueous aerosol mass concentration. The γ for IEPOX is mostly determined by the rate of H+-catalyzed ring opening in the aqueous phase.

Application of our mechanism to the Southeast US indicates a mean isoprene SOA yield of 3.3% on a mass basis. By contrast, a conventional mechanism based on reversible uptake of semivolatile isoprene oxidation products yields only 1.1%. Simulation of the observed relationship of OA with formaldehyde (HCHO) provides support for our higher yield. We find that the low-NOx pathway is 5 times more efficient than the high-NOx pathway for isoprene SOA production. Under Southeast US conditions, IEPOX and glyoxal account respectively for 58% and 28% of isoprene SOA.

Our model simulates well the observations and variability of IEPOX SOA at the surface and from aircraft. The observations show a strong correlation with sulfate that we reproduce in the model. We find this is due to the effect of sulfate on aerosol pH and volume concentration, increasing IEPOX uptake by the H+-catalyzed ring-opening mechanism. Low concentrations of sulfate are associated with very low IEPOX SOA, both in the observations and the model, and we attribute this to the compounding effects of low sulfate on aerosol [H+] and on aerosol volume.

The US EPA has projected that US NOx and SO2 emissions will decrease by 34 and 48% respectively from 2013 to 2025. We find in our model that the NOx reduction will increase isoprene SOA by 7%, reflecting greater importance of the low-NOx pathway. The SO2 reduction will decrease isoprene SOA by 35%, due to decreases in both aerosol [H+] and volume concentration. The combined effect of these two changes is to decrease isoprene SOA by 32%, corresponding to a decrease in the isoprene SOA mass yield from 3.3% to 2.3%. Decreasing SO2 emissions by 48% has similar relative effects on sulfate (36%) and isoprene SOA (35%). Considering that sulfate presently accounts for about 30% of PM2.5 in the Southeast US in summer, while isoprene SOA contributes 25%, we conclude that decreasing isoprene SOA represents a factor of 2 co-benefit when reducing SO2 emissions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the entire NASA SEAC4RS team for their help in the field, in particular Paul Wennberg, John Crounse, Jason St. Clair, and Alex Teng for their CIT-CIMS measurements. Thanks also to Jesse Kroll for assisting in the interpretation of chamber study results. This work was funded by the NASA Tropospheric Chemistry Program, the NASA Air Quality Applied Sciences Team, and a South African National Research Foundation Fellowship and Schlumberger Faculty for the Future Fellowship to EAM. WH, JEK, PCJ, DAD, and JLJ were supported by NASA NNX12AC03G/NNX15AT96G and NSF AGS-1243354. JEK was supported by EPA STAR (FP-91770901-0) and CIRES Fellowships. JAF acknowledges support from a University of Wollongong Vice Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship. HCHO observations were acquired with support from NASA ROSES SEAC4RS grant NNH10ZDA001N. Although this document has been reviewed by U.S. EPA and approved for publication, it does not necessarily reflect U.S. EPA’s policies or views.

References

- Anttila T, Kiendler-Scharr A, Tillmann R, and Mentel TF: On the reactive uptake of gaseous compounds by organic-coated aqueous aerosols: Theoretical analysis and application to the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110, 10435–10443, doi: 10.1021/jp062403c, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood AR, Washenfelder RA, Brock CA, Hu W, Baumann K, Campuzano-Jost P, Day DA, Edgerton ES, Murphy DM, Palm BB, McComiskey A, Wagner NL, de Sá SS, Ortega A, Martin ST, Jimenez JL, and Brown SS: Trends in sulfate and organic aerosol mass in the Southeast U.S.: Impact on aerosol optical depth and radiative forcing, Geophys. Res. Lett, 41, 7701–7709, doi: 10.1002/2014gl061669, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AP, Bertram AK, and Martin ST: Hygroscopic influence on the semisolid-to-liquid transition of secondary organic materials, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 4386–4395, doi: 10.1021/jp508521c, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates KH, Crounse JD, St Clair JM, Bennett NB, Nguyen TB, Seinfeld JH, Stoltz BM, and Wennberg PO: Gas phase production and loss of isoprene epoxydiols, J. Phys. Chem. A, 118, 1237–1246, doi: 10.1021/jp4107958, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brégonzio-Rozier L, Giorio C, Siekmann F, Pangui E, Morales SB, Temime-Roussel B, Gratien A, Michoud V, Cazaunau M, DeWitt HL, Tapparo A, Monod A, and Doussin J-F: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation during cloud condensation–evaporation cycles, Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss, 15, 20561–20596, doi: 10.5194/acpd-15-20561-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SS, De Gouw JA, Warneke C, Ryerson TB, Dubé WP, Atlas E, Weber RJ, Peltier RE, Neuman JA, Roberts JM, Swanson A, Flocke F, McKeen SA, Brioude J, Sommariva R, Trainer M, Fehsenfeld FC, and Ravishankara AR: Nocturnal isoprene oxidation over the Northeast United States in summer and its impact on reactive nitrogen partitioning and secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 3027–3042, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-3027-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budisulistiorini SH, Canagaratna MR, Croteau PL, Marth WJ, Baumann K, Edgerton ES, Shaw SL, Knipping EM, Worsnop DR, Jayne JT, Gold A, and Surratt JD: Real-time continuous characterization of secondary organic aerosol derived from isoprene epoxydiols in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, using the Aerodyne aerosol chemical speciation monitor, Environ. Sci. Technol, 47, 5686–5694, doi: 10.1021/es400023n, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budisulistiorini SH, Li X, Bairai ST, Renfro J, Liu Y, Liu YJ, McKinney KA, Martin ST, McNeill VF, Pye HOT, Nenes A, Neff ME, Stone EA, Mueller S, Knote C, Shaw SL, Zhang Z, Gold A, and Surratt JD: Examining the effects of anthropogenic emissions on isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol formation during the 2013 Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study (SOAS) at the Look Rock, Tennessee ground site, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 8871–8888, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-8871-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton GV, Malone TN, and Salmon GA: Oxidation of glyoxal initiated by •OH in oxygenated aqueous solution, J Chem. Soc. Faraday T, 93, 2889–2891, doi 10.1039/A701468f, 1997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canagaratna MR, Jayne JT, Jimenez JL, Allan JD, Alfarra MR, Zhang Q, Onasch TB, Drewnick F, Coe H, Middlebrook A, Delia A, Williams LR, Trimborn AM, Northway MJ, DeCarlo PF, Kolb CE, Davidovits P, Worsnop DR: Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 26, 185–222, doi: 10.1002/mas.20115, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton AG, Turpin BJ, Altieri KE, Seitzinger SP, Mathur R, Roselle SJ, and Weber RJ: CMAQ model performance enhanced when in-cloud secondary organic aerosol is included: Comparisons of organic carbon predictions with measurements, Environ. Sci. Technol, 42, 8789–8802, doi:1021/es801192n, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton AG, Wiedinmyer C, and Kroll JH: A review of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation from isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 4987–5005, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-4987-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton AG, and Turpin BJ: Particle partitioning potential of organic compounds is highest in the Eastern US and driven by anthropogenic water, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 13, 10203–10214, doi: 10.5194/acp-13-10203-2013, 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, Wolfe GM, Bailey SA, Swanson AK, Arkinson HL, and Hanisco TF: A new airborne laser-induced fluorescence instrument for in situ detection of formaldehyde throughout the troposphere and lower stratosphere, Atmos. Meas. Tech, 8, 541–552, doi: 10.5194/amt-8-541-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWH, Chan MN, Surratt JD, Chhabra PS, Loza CL, Crounse JD, Yee LD, Flagan RC, Wennberg PO, and Seinfeld JH: Role of aldehyde chemistry and NOx concentrations in secondary organic aerosol formation, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 10, 7169–7188, doi: 10.5194/acp-10-7169-2010, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Filipiak NC, O’Connor AE, and Elrod MJ: Kinetics of the hydrolysis of atmospherically relevant isoprene-derived hydroxy epoxides, Environ. Sci. Technol, 44, 6718–6723, doi: 10.1021/es1019228, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darer AI, Cole-Filipiak NC, O’Connor AE, and Elrod MJ: Formation and stability of atmospherically relevant isoprene-derived organosulfates and organonitrates, Environ. Sci. Technol, 45, 1895–1902, doi: 10.1021/es103797z, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo PF, Kimmel JR Trimborn A, Northway MJ, Jayne JT, Aiken AC, Gonin M, Fuhrer K, Horvath T, Docherty KS, Worsnop DR, and Jimenez JL: Field-deployable, High-Resolution, Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, Anal. Chem, 78, 8281–8289, doi: 10.1021/ac061249n, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dommen J, Metzger A, Duplissy J, Kalberer M, Alfarra MR, Gascho A, Weingartner E, Prévôt ASH, Verheggen B, and Baltensperger U: Laboratory observation of oligomers in the aerosol from isoprene/NOx photooxidation, Geophys. Res. Lett, 33, L13805, doi: 10.1029/2006gl026523, 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue NM, Robinson AL, Stanier CO, and Pandis SN: Coupled partitioning, dilution, and chemical aging of semivolatile organics, Environ. Sci. Technol, 40, 2635–2643, doi: 10.1021/es052297c, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury E, Jacob DJ, Spurr RJD, Wang J, Shinozuka Y, Anderson BE, Clarke AD, Dibb J, McNaughton C, and Weber R: Synthesis of satellite (MODIS), aircraft (ICARTT), and surface (IMPROVE, EPA-AQS, AERONET) aerosol observations over eastern North America to improve MODIS aerosol retrievals and constrain surface aerosol concentrations and sources, J. Geophys. Res, 115, D14204, doi: 10.1029/2009jd012629, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA: U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Technical Support Document (TSD): Preparation of Emissions Inventories for the Version 6.1, 2011 Emissions Modeling Platform, available at: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/emch/2011v6/2011v6.1_2018_2025_base_EmisMod_TSD_nov2014_v6.pdf (Accessed on July 15, 2015), 2014.

- Eddingsaas NC, VanderVelde DG, and Wennberg PO: Kinetics and products of the acid-catalyzed ring-opening of atmospherically relevant butyl epoxy alcohols, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 8106–8113, doi: 10.1021/jp103907c, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edney EO, Kleindienst TE, Jaoui M, Lewandowski M, Offenberg JH, Wang W, and Claeys M: Formation of 2-methyl tetrols and 2-methylglyceric acid in secondary organic aerosol from laboratory irradiated isoprene/NOx/SO2/air mixtures and their detection in ambient PM2.5 samples collected in the eastern United States, Atmos. Environ, 39, 5281–5289, doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.05.031, 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ervens B, Gligorovski S, and Herrmann H: Temperature-dependent rate constants for hydroxyl radical reactions with organic compounds in aqueous solutions, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 5, 1811–1824, doi: 10.1039/b300072a, 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ervens B, Turpin BJ, and Weber RJ: Secondary organic aerosol formation in cloud droplets and aqueous particles (aqSOA): A review of laboratory, field and model studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 11, 11069–11102, doi: 10.5194/acp-11-11069-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JA, Jacob D, Travis KR, Kim PS, Marais EA, Miller CC, Yu K, Zhu L, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Mao J, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, Teng AP, Nguyen TB, Cohen RC, Romer P, Nault BA, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Shepson PB, Xiong F, Blake DR, Goldstein AH, Hanisco TF, Ryerson TB, Wisthaler A, and Mikoviny T: Organic nitrate chemistry and its implications for nitrogen budgets in and isoprene- and monoterpene-rich atmosphere: constraints from aircraft (SEAC4RS) and ground-based (SOAS) observations in the Southeast US, in preparation, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fountoukis C, and Nenes A: ISORROPIA II: A computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+-Ca2+-Mg2+-NH4+-Na+-SO42--NO3--Cl−-H2O aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 7, 4639–4659, doi: 10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007, 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T-M, Jacob DJ, Wittrock F, Burrows JP, Vrekoussis M, and Henze DK: Global budgets of atmospheric glyoxal and methylglyoxal, and implications for formation of secondary organic aerosols, J. Geophys. Res, 113, D15303, doi: 10.1029/2007jd009505, 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T-M, Jacob DJ, and Heald CL: Aqueous-phase reactive uptake of dicarbonyls as a source of organic aerosol over eastern North America, Atmos. Environ, 43, 1814–1822, doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.12.029, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston CJ, Riedel TP, Zhang Z, Gold A, Surratt JD, and Thornton JA: Reactive uptake of an isoprene-derived epoxydiol to submicron aerosol particles, Environ. Sci. Technol, 48, 11178–11186, doi: 10.1021/es5034266, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Abad GG, Liu X, Chance K, Wang H, Kurosu TP, and Suleiman R: Updated Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Ozone Monitoring Instrument (SAO OMI) formaldehyde retrieval, Atmos. Meas. Tech, 8, 19–32, doi: 10.5194/amt-8-19-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A, Karl T, Harley P, Wiedinmyer C, Palmer PI, and Geron C: Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature), Atmos. Chem. Phys, 6, 3181–3210, doi: 10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006, 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther AB, Jiang X, Heald CL, Sakulyanontvittaya T, Duhl T, Emmons LK, and Wang X: The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): An extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions, Geosci. Model Dev, 5, 1471–1492, doi: 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012, 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Xu L, Bougiatioti A, Cerully KM, Capps SL, Hite JR Jr., Carlton AG, Lee S-H, Bergin MH, Ng NL, Nenes A, and Weber RJ: Fine-particle water and pH in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 5211–5228, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-5211-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist M, Wenger JC, Baltensperger U, Rudich Y, Simpson D, Claeys M, Dommen J, Donahue NM, George C, Goldstein AH, Hamilton JF, Herrmann H, Hoffmann T, Iinuma Y, Jang M, Jenkin ME, Jimenez JL, Kiendler-Scharr A, Maenhaut W, McFiggans G, Mentel Th. F., Monod A, Prévôt ASH, Seinfeld JH, Surratt JD, Szmigielski R, and Wildt J: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: Current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 5155–5236, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-5155-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess M, Koepke P, and Schult I: Optical properties of aerosols and clouds: The software package OPAC, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc, 79, 831–844, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hodzic A, and Jimenez JL: Modeling anthropogenically controlled secondary organic aerosols in a megacity: A simplified framework for global and climate models, Geosci. Model. Dev, 4, 901–917, doi: 10.5194/gmd-4-901-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu KS, Darer AI, and Elrod MJ: Thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydrolysis of atmospherically relevant organonitrates and organosulfates, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 11, 8307–8320, doi: 10.5194/acp-11-8307-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WW, Campuzano-Jost P, Palm BB, Day DA, Ortega AM, Hayes PL, Krechmer JE, Chen Q, Kuwata M, Liu YJ, de Sá SS, Martin ST, Hu M, Budisulistiorini SH, Riva M, Surratt JD, Clair JM St., Isaacman-Van Wertz G, Yee LD, Goldstein AH, Carbone S, Artaxo P, de Gouw JA, Koss A, Wisthaler A, Mikoviny T, Karl T, Kaser L, Jud W, Hansel A Docherty KS, Robinson NH, Coe H, Allan JD, Canagaratna MR, Paulot F, and Jimenez JL: Characterization of a real-time tracer for isoprene epoxydiols-derived secondary organic aerosol (IEPOX-SOA) from aerosol mass spectrometer measurements, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 11807–11833, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-11807-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob DJ: Heterogeneous chemistry and tropospheric ozone, Atmos. Environ, 34, 2131–2159, doi: 10.1016/s1352-2310(99)00462-8, 2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MI, Darer AI, and Elrod MJ: Rate constants and products of the OH reaction with isoprene-derived epoxides, Environ. Sci. Technol, 47, 12868–12876, doi: 10.1021/es403340g, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MI, Burke WJ, and Elrod MJ: Kinetics of the reactions of isoprene-derived hydroxynitrates: Gas phase epoxide formation and solution phase hydrolysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 14, 8933–8946, doi: 10.5194/acp-14-8933-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PS, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Travis K, Yu K, Zhu L, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Froyd KD, Liao J, Hair JW, Fenn MA, Butler CF, Wagner NL, Gordon TD, Welti A, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, Clair JM St., Teng AP, Millet DB, Schwarz JP, Markovic MZ, and Perring AE: Sources, seasonality, and trends of southeast US aerosol: an integrated analysis of surface, aircraft, and satellite observations with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 10411–10433, doi: 10.5194/acpd-15-10411-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Rosenoern T, Shilling JE, Chen Q, Wang Z, Biskos G, McKinney KA, Pöschl U, and Martin ST: Cloud droplet activation of mixed organic-sulfate particles produced by the photooxidation of isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 10, 3953–3964, doi: 10.5194/acp-10-3953-2010, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst TE, Edney EO, Lewandowski M, Offenberg JH, and Jaoui M: Secondary organic carbon and aerosol yields from the irradiations of isoprene and α-pinene in the presence of NOx and SO2, Environ. Sci. Technol, 40, 3807–3812, doi: 10.1021/es052446r, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst TE, Lewandowski M, Offenberg JH, Jaoui M, and Edney EO: Ozone-isoprene reaction: Re-examination of the formation of secondary organic aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett, 34, L01805, doi: 10.1029/2006gl027485, 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst TE, Lewandowski M, Offenberg JH, Jaoui M, and Edney EO: The formation of secondary organic aerosol from the isoprene + OH reaction in the absence of NOx, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 6541–6558, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-6541-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knote C, Hodzic A, Jimenez JL, Volkamer R, Orlando JJ, Baidar S, Brioude J, Fast J, Gentner DR, Goldstein AH, Hayes PL, Knighton WB, Oetjen H, Setyan A, Stark H, Thalman R, Tyndall G, Washenfelder R, Waxman E, and Zhang Q: Simulation of semi-explicit mechanisms of SOA formation from glyoxal in aerosol in a 3-D model, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 14, 6213–6239, doi: 10.5194/acp-14-6213-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke P, Hess M, Schult I, and Shettle EP: Global aerosol data set, report, Max-Planck Inst. für Meteorol., Hamburg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krechmer JE, Coggon MM, Massoli P, Nguyen TB, Crounse JD, Hu W, Day DA, Tyndall GS, Henze DK, Rivera-Rios JC, Nowak JB, Kimmel JR, Mauldin RL III, Stark H, Jayne JT, Sipilä M, Junninen H, Clair JM St., Zhang X, Feiner PA, Zhang L, Miller DO, Brune WH, Keutsch FN, Wennberg PO, Seinfeld JH, Worsnop DR, Jimenez JL, and Canagaratna MR: Formation of low volatility organic compounds and secondary organic aerosol from isoprene hydroxyhydroperoxide low-NO oxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol, 49, 10330–10339, doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02031, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JH, Ng NL, Murphy SM, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation under high-NOx conditions, Geophys. Res. Lett, 32, L18808, doi: 10.1029/2005gl023637, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JH, Ng NL, Murphy SM, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol, 40, 1869–1877, doi: 10.1021/es0524301, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Teng AP, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, and Cohen RC: On rates and mechanisms of OH and O3 reactions with isoprene-derived hydroxy nitrates, J. Phys. Chem. A, 118, 1622–1637, doi: 10.1021/jp4107603, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski M, Jaoui M, Offenberg JH, Krug JD, and Kleindienst TE: Atmospheric oxidation of isoprene and 1,3-butadiene: Influence of aerosol acidity and relative humidity on secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 3773–3783, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-3773-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Froyd KD, Murphy DM, Keutsch FN, Yu G, Wennberg PO, St Clair JM, Crounse JD, Wisthaler A, Mikoviny T, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Day DA, Hu W, Ryerson TB, Pollack IB, Peischl J, Anderson BE, Ziemba LD, Blake DR, Meinardi S, and Diskin G: Airborne measurements of organosulfates over the continental U.S., J. Geophys. Res, 120, 2990–3005, doi: 10.1002/2014jd022378, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggio J, Li S-M, and McLaren R: Reactive uptake of glyoxal by particulate matter, J. Geophys. Res, 110, D10304, doi: 10.1029/2004jd005113, 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y-H, Zhang H, Pye HOT, Zhang ZF, Marth WJ, Park S, Arashiro M, Cui T, Budisulistiorini SH, Sexton KG, Vizuete W, Xie Y, Luecken DJ, Piletic IR, Edney EO, Bartolotti LJ, Gold A, and Surratt JD: Epoxide as a precursor to secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation in the presence of nitrogen oxides, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 6718–6723, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221150110, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Herdlinger-Blatt I, McKinney KA, and Martin ST: Production of methyl vinyl ketone and methacrolein via the hydroperoxyl pathway of isoprene oxidation, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 13, 5715–5730, doi: 10.5194/acp-13-5715-2013, 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Sillman S, Penner JE, and Ito A, Global modeling of SOA: the use of different mechanisms for aqueous-phase formation, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 14, 5451–5475, doi: 10.5194/acp-14-5451-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Horowitz LW, Fan S, Carlton AG, and Levy II H, Global in-cloud production of secondary organic aerosols: implementation of a detailed chemical mechanism in the GFDL atmospheric model AM3, J. Geosphys. Res, D117, D15303, doi: 10.1029/2012JD017838, 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Paulot F, Jacob DJ, Cohen RC, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO, Keller CA, Hudman RC, Barkley MP, and Horowitz LW: Ozone and organic nitrates over the eastern United States: Sensitivity to isoprene chemistry, J. Geophys. Res, 118, 11256–11268, doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50817, 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RV, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Chin M, and Ginoux P: Global and regional decreases in tropospheric oxidants from photochemical effects of aerosols, J. Geophys. Res, 108, 4097, doi: 10.1029/2002jd002622, 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill VF, Woo JL, Kim DD, Schwier AN, Wannell NJ, Sumner AJ, and Barakat JM: Aqueous-phase secondary organic aerosol and organosulfate formation in atmospheric aerosols: A modeling study, Environ. Sci. Technol, 46, 8075–8081, doi: 10.1021/es3002986, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill VF, Sareen N, and Schwier AN: Surface-active organics in atmospheric aerosols, Top. Curr. Chem, 339, 201–259, doi: 10.1007/128_2012_404, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet DB, Jacob DJ, Turquety S, Hudman RC, Wu S, Fried A, Walega J, Heikes BG, Blake DR, Singh HB, Anderson BE, and Clarke AD: Formaldehyde distribution over North America: Implications for satellite retrievals of formaldehyde columns and isoprene emission, J. Geophys. Res, 111, D24S02, doi: 10.1029/2005jd006853, 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myriokefalitakis S, Tsigaridas K, Mihalopoulos N, Sciare J, Nenes A, Kawamura K, Segers A, and Kanakidou M: In-cloud oxalate formation in the global troposphere: a 3-D modeling study, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 11, 5761–5782, doi: 10.5194/acp-11-5761-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng NL, Kwan AJ, Surratt JD, Chan AWH, Chhabra PS, Sorooshian A, Pye HOT, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation from reaction of isoprene with nitrate radicals (NO3), Atmos. Chem. Phys, 8, 4117–4140, doi: 10.5194/acp-8-4117-2008, 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TB, Coggon MM, Bates KH, Zhang X, Schwantes RH, Schilling KA, Loza CL, Flagan RC, Wennberg PO, and Seinfeld JH: Organic aerosol formation from the reactive uptake of isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX) onto non-acidified inorganic seeds, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 14, 3497–3510, doi: 10.5194/acp-14-3497-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TB, Crounse JD, Teng AP, Clair JM St., Paulot F, Wolfe GM, and Wennberg PO: Rapid deposition of oxidized biogenic compounds to a temperate forest, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, E392–E401, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418702112, 2015a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TB, Bates KH, Crounse JD, Schwantes RH, Zhang X, Kjaergaard HG, Surratt JD, Lin P, Laskin A, Seinfeld JH, and Wennberg PO: Mechanism of the hydroxyl radical oxidation of methacryloyl peroxynitrate (MPAN) and its pathway toward secondary organic aerosol formation in the atmosphere, Phys Chem Chem Phys, 17, 17914–17926, doi: 10.1039/c5cp02001h, 2015b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozière B, Dziedzic P, and Córdova A: Products and kinetics of the liquid-phase reaction of glyoxal catalyzed by ammonium ions (NH4+), J. Phys. Chem. A, 113, 231–237, doi: 10.1021/jp8078293, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum JR, Hoffmann T, Bowman F, Collins D, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Gas/particle partitioning and secondary organic aerosol yields, Environ. Sci. Technol, 30, 2580–2585, doi: 10.1021/es950943+, 1996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer PI, Jacob DJ, Fiore AM, Martin RV, Chance K, and Kurosu TP: Mapping isoprene emissions over North America using formaldehyde column observations from space, J. Geophys. Res, 108, 4180, doi: 10.1029/2002jd002153, 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer PI, Abbot DS, Fu T-M, Jacob DJ, Chance K, Kurosu TP, Guenther A, Wiedinmyer C, Stanton JC, Pilling MJ, Pressley SN, Lamb B, and Sumner AL: Quantifying the seasonal and interannual variability of North American isoprene emissions using satellite observations of the formaldehyde column, J. Geophys. Res, 111, D12315, doi: 10.1029/2005jd006689, 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulot F, Crounse JD, Kjaergaard HG, Kroll JH, Seinfeld JH, and Wennberg PO: Isoprene photooxidation: New insights into the production of acids and organic nitrates, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 1479–1501, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-1479-2009, 2009a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulot F, Crounse JD, Kjaergaard HG, Kürten A, St Clair JM, Seinfeld JH, and Wennberg PO: Unexpected epoxide formation in the gas-phase photooxidation of isoprene, Science, 325, 730–733, doi: 10.1126/science.1172910, 2009b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J, Nguyen TL, and Vereecken L: HOx radical regeneration in the oxidation of isoprene, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 11, 5935–5939, doi: 10.1039/b908511d, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J, and Müller J-F: HOx radical regeneration in isoprene oxidation via peroxy radical isomerisations. II: Experimental evidence and global impact, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 12, 14227–14235, doi: 10.1039/c0cp00811g, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piletic IR, Edney EO, and Bartolotti LJ: A computational study of acid catalyzed aerosol reactions of atmospherically relevant epoxides, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 15, 18065–18076, doi: 10.1039/c3cp52851k, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pye HOT, Chan AWH, Barkley MP, and Seinfeld JH: Global modeling of organic aerosol: The importance of reactive nitrogen (NOx and NO3), Atmos. Chem. Phys, 10, 11261–11276, doi: 10.5194/acp-10-11261-2010, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pye HOT, Pinder RW, Piletic IR, Xie Y, Capps SL, Lin Y-H, Surratt JD, Zhang Z, Gold A, Luecken DJ, Hutzell WT, Jaoui M, Offenberg JH, Kleindienst TE, Lewandowski M, and Edney EO: Epoxide pathways improve model predictions of isoprene markers and reveal key role of acidity in aerosol formation, Environ. Sci. Technol, 47, 11056–11064, doi: 10.1021/es402106h, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel TP, Lin Y-H, Budisulistiorini SH, Gaston CJ, Thornton JA, Zhang ZF, Vizuete W, Gold A, and Surratt JD: Heterogeneous reactions of isoprene-derived epoxides: Reaction probabilities and molar secondary organic aerosol yield estimates, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett, 2, 38–42, doi: 10.1021/ez500406f, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins AW, Kiendler-Scharr A, Fry JL, Brauers T, Brown SS, Dorn H-P, Dubé WP, Fuchs H, Mensah A, Mentel TF, Rohrer F, Tillmann R, Wegener R, Wooldridge PJ, and Cohen RC: Isoprene oxidation by nitrate radical: Alkyl nitrate and secondary organic aerosol yields, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 6685–6703, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-6685-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SEAC4RS Archive, doi: 10.5067/Aircraft/SEAC4RS/Aerosol-TraceGas-Cloud. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Nakao S, Clark CH, Qi L, and Cocker III DR: Secondary organic aerosol formation from the photooxidation of isoprene, 1,3-butadiene, and 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene under high NOx conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 11, 7301–7317, doi: 10.5194/acp-11-7301-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P, and Hildemann LM: Water-soluble organics in atmospheric particles: A critical review of the literature and application of thermodynamics to identify candidate compounds, J. Atmos. Chem, 24, 57–109, doi: 10.1007/bf00053823, 1996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SE: Mass-transport considerations pertinent to aqueous-phase reactions of gases in liquid-water clouds In: Jaechske W (Ed.), Chemistry of Multiphase Atmospheric Systems, Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 415.–471, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CE, Rap A, Spracklen DV, Forster PM, Carslaw KS, Mann GW, Pringle KJ, Kivekäs N, Kulmala M, Lihavainen H, and Tunved P: The direct and indirect radiative effects of biogenic secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 14, 447–470, doi: 10.5194/acp-14-447-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Liu PF, Hanna SJ, Li YJ, Martin ST, and Bertram AK: Relative humidity-dependent viscosities of isoprene-derived secondary organic material and atmospheric implications for isoprene-dominant forests, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 5145–5159, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-5145-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakou T, Peeters J, and Müller J-F: Improved global modelling of HOx recycling in isoprene oxidation: Evaluation against the GABRIEL and INTEX-A aircraft campaign measurements, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 10, 9863–9878, doi: 10.5194/acp-10-9863-2010, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clair JM St., Rivera-Rios JC, Crounse JD, Knap HC, Bates KH, Teng AP, Jørgensen S, Kjaergaard HG, Keutsch FN, Wennberg PO: Kinetics and products of the reaction of the first-generation isoprene hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH) with OH, J. Phys. Chem. A, doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06532, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner AJ, Woo JL, and McNeill VF: Model Analysis of secondary organic aerosol formation by glyoxal in laboratory studies: The case for photoenhanced chemistry, Environ. Sci. Technol, 48, 11919–11925, doi: 10.1021/es502020j, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt JD, Murphy SM, Kroll JH, Ng NL, Hildebrandt L, Sorooshian A, Szmigielski R, Vermeylen R, Maenhaut W, Claeys M, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Chemical composition of secondary organic aerosol formed from the photooxidation of isoprene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110, 9665–9690, doi: 10.1021/jp061734m, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt JD, Lewandowski M, Offenberg JH, Jaoui M, Kleindienst TE, Edney EO, and Seinfeld JH: Effect of acidity on secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene, Environ. Sci. Technol, 41, 5363–5369, doi: 10.1021/es0704176, 2007a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt JD, Kroll JH, Kleindienst TE, Edney EO, Claeys M, Sorooshian A, Ng NL, Offenberg JH, Lewandowski M, Jaoui M, Flagan RC, and Seinfeld JH: Evidence for organosulfates in secondary organic aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol, 41, 517–527, doi: 10.1021/es062081q, 2007b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt JD, Chan AWH, Eddingsaas NC, Chan M, Loza CL, Kwan AJ, Hersey SP, Flagan RC, Wennberg PO, and Seinfeld JH: Reactive intermediates revealed in secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6640–6645, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911114107, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Perri MJ, Seitzinger SP, and Turpin BJ: Effects of precursor concentration and acidic sulfate in aqueous glyoxal-OH radical oxidation and implications for secondary organic aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol, 43, 8105–8112, doi: 10.1021/es901742f, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Carlton AG, Seitzinger SP, and Turpin BJ: SOA from methylglyoxal in clouds and wet aerosols: Measurement and prediction of key products, Atmos. Environ, 44, 5218–5226, doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.08.045, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toon OB and the SEAC4RS science team: Planning, implementation, and scientific goals of the Studies of Emissions and Atmospheric Composition, Clouds, and Climate Coupling by Regional Surveys (SEAC4RS) field mission, submitted to J. Geosphys. Res, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Travis KR, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Kim PS, Marais EA, Zhu L, Miller CC, Wennberg PO, Crounse J, Hanisco TA, Ryerson T, Yu K, Wolfe GM, Thompson A, Mao J, Paulot F, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio M, and Neuman A: NOx emissions, isoprene oxidation pathways, and implications for surface ozone in the Southeast United States, in preparation, 2016.

- Virtanen A, Joutsensaari J, Koop T, Kannosto J, Yli-Pirilä P, Leskinen J, Mäkelä JM, Holopainen JK, Pöschl U, Kulmala M, Worsnop DR, and Laaksonen A: An amorphous solid state of biogenic secondary organic aerosol particles, Nature, 467, 824–827, doi: 10.1038/nature09455, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkamer R, Martini FS, Molina LT, Salcedo D, Jimenez JL, and Molina MJ: A missing sink for gas-phase glyoxal in Mexico City: Formation of secondary organic aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett, 34, L19807, doi: 10.1029/2007gl030752, 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volkamer R, Ziemann PJ, and Molina MJ: Secondary organic aerosol formation from acetylene (C2H2): Seed effect on SOA yields due to organic photochemistry in the aerosol aqueous phase, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 1907–1928, doi: 10.5194/acp-9-1907-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner NL, Brock CA, Angevine WM, Beyersdorf A, Campuzano-Jost P, Day D, de Gouw JA, Diskin GS, Gordon TD, Graus MG, Holloway JS, Huey G, Jimenez JL, Lack DA, Liao J, Liu X, Markovic MZ, Middlebrook AM, Mikoviny T, Peischl J, Perring AE, Richardson MS, Ryerson TB, Schwarz JP, Warneke C, Welti A, Wisthaler A, Ziemba LD, and Murphy DM: In situ vertical profiles of aerosol extinction, mass, and composition over the southeast United States during SENEX and SEAC4RS: Observations of a modest aerosol enhancement aloft, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 7085–7102, doi: 10.5194/acp-15-7085-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]