Abstract

This study focuses on patterns and influences of return migration behavior in mainland China, (n = 468 individuals ages 50 and above) from a life-course perspective, using the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Utilizing spatial analysis, we found return migration geographic patterns mainly from the frontier and urban centers to central provinces, involving migrant workers returning to their rural homes. We used logistic linear modeling to examine the correlations between personal attributes (e.g., age, gender, marital status), environmental aspects (e.g., community characteristics, housing conditions, geographic attributes), and return migration. Historical and socioeconomic factors affected return migration, including availability parents to provide care, declining personal health, improved housing infrastructures, and better access to community services. Our findings also show the productive social role of caregiving as a reason for migration, calling for flexible policies in China’s social welfare system, comprehensive senior living facilities, and adequate support systems in rural communities.

Keywords: Return migrants, Rural area, Migration patterns, China, Relocation, Caregiving

Introduction

Relocation and migration research often intersect, aiming to understand an older adult’s relationship with his/her home and possessions, kin network and community and the experiences of exchanging one cultural and social milieu for another (Perry et al. 2013; Perry 2014; Rowles and Watkins 2003). In this paper, rather than relocation/migration towards something new, we focus on experiences of “returning back” to familiar locations. We aim to understand the complexities of returning to such territory and the impact on one’s social roles and housing opportunities. Return migration behavior in China in later life is occurring increasingly, due to changing family support systems and diversified elder care choices (Dou and Liu 2015; Lu and Song 2006; Omelaniuk 2005; Tong and Piotrowski 2012). The motivations that influence return migration behavior and the experience after the migration have rarely been discussed.

This study aims to understand the characteristics of return migrants and identify factors and patterns associated with return migration. Using data from the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) national baseline, we used logistic linear modeling to examine the correlations between personal attributes (e.g., age, gender, and marital status), environmental aspects (e.g., community characteristics, housing conditions, and geographic attributes) and return behavior. In addition, we applied spatial analysis to explore the geographical patterns of return migration, using Geographic Information System (GIS) technology. This study fulfills gaps in the literature on return migration in China using such detailed analytical approaches on a country-wide scale. In the conclusion, we discuss implications for guiding policymakers and government administrators to recognize and understand issues confronting return migrants, and how to create aging-friendly communities that help return migrants achieve their goal of moving and improve their quality of life.

Theoretical Framework

Life Course Theory

The framework for this study is life course theory, which acknowledges varying life pathways for those of different cohorts, due to differing social and political historical moments. This perspective is especially applicable for older Chinese who have witnessed governmental and economic changes (e.g., modernization of industries) in their lifetime. Older Chinese, like many elderly persons around the globe, have also experienced unprecedented urbanization, along with concomitant changes in family structures and living arrangements.

Our selection of variables and analysis of the older adults return migration motivations was driven by the major tenets and assumptions of the life-course perspective. Cohort focuses on a group of persons who were born at the same historical time or who experience particular social changes within a given culture or at the same age. Transition refers to changes in roles and statuses. Trajectory considers the long-term pattern of stability and change, (usually involves multiple transitions.) Life event refers to significant events with relatively dramatic changes that may lead to serious and long-lasting effects. Turning points, which refer to life events that produce lasting shifts in the life-course trajectory (Elder 1998). Therefore, the cohort we are using in this study are those born between 1920s and 1960s, who have experienced social changes within the culture of China. Analyzing the personal attributes and environmental aspect variables reveals whether participants have experienced changes in roles and statuses due to migration. Furthermore, the CHARLS helps to analyze long-term patterns of housing stability or change.

Life course theory emphasizes the interplay of human lives and historical times, so historical economic and social events should be considered to explain the motivations for return migration in later life. In addition, life-course theory emphasizes human agency in making choices; return migration is constrained by the choices and actions that elderly migrants take within the opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstances. Life-course theory incorporates diversity, developmental risk, and protection in life-course trajectories, so we assume that older adults’ return migration patterns and influences are diverse, due to cohort variations, social class, culture, gender, and individual differences. In terms of consequences, the elder return migrants’ experiences in earlier life have an impact later in life, and may bring either positive or negative effects (Elder 1998). By using life-course theory in our study, we integrate rapid historical change into understanding return migration.

Background

Influencing Factors

Since the 1970s, research has focused on migration and return migration in later life in Europe and America. Previous researchers concluded that the major reasons for relocation in later life include residential style and satisfaction, economic factors, and geographic attributes, among other factors (Conway and Rork 2010; Lawton 1980; Litwak and Longino Jr. 1987; Walters 2002; Wiseman and Roseman 1979; Gubernskaya 2015).

Residential Style and Satisfaction

Residential satisfaction is directly contingent upon background circumstances such as individual needs, housing quality and housing facilities, neighborhood factors, and social ties to one’s community (Markides and Eschbach 2005; Stoller and Longino 2001). Dissatisfaction with current residential conditions and expectations of ideal housing facilities are common motivations for moving; older people with higher levels of residential satisfaction tended to remain in their current living arrangements (Lawton 1980; Speare et al. 1991; Walters 2002). Older adults move for a variety of reasons, depending on their health conditions, preferences, and financial means (Perry 2015; Wiseman 1980). Litwak and Longino Jr. (1987) suggest that amenity- or lifestyle-driven moves, or pursuit of an ideal retirement lifestyle, are the first typical conditions underlying relocation in late life. Two other types of relocations are assistance moves, that is moving closer to kin to achieve assistance demanded by decreasing competence. The second ones are nursing home moves, which occur to secure specific care for older adults who need attention beyond family support (Litwak and Longino Jr. 1987). We apply these relocation factors to understand return migration.

Economic Factors

Economic factors influence return migration (Crown 1988; Haas et al. 2006; Stark and Taylor 1989). Stark and Taylor (1989, 1991) used the concept of “relative deprivation” to explain return migration between Mexico and the United States; they suggested that an important motivation of return migration is to reduce the sense of relative poverty. Individuals with relatively low income compared to the average income level would experience economic challenges, which might motivate (Stark and Taylor 1991). They assumed the decision of migration was based on both the pulling force of the income gap, and the relative income gap between households. Dustmann (1997) built an individual welfare maximization model to analyze the life cycle of relocation and return migration, based on the phenomenon of migrant workers in Switzerland, Germany, France, and other European countries. He believed that three factors influenced the flow of migrant workers: (1) the ratio of the relative prices between the hometown and the current living city, (2) the migrants’ subjective preferences, and (3) accumulated resources in the current living cities, which can play a significant role deciding to live in rural areas. When workers made migration decisions by the comparison of benefits and cost, assessment of maximization of career earnings occurred (Dustmann 1997).

Geographic Attributes and Population Attributes

Previous researchers also indicated that geographic attributes, aging populations, and racial similarity were important factors impacting return migration (Gubernskaya 2015; Newbold 1999; Hogan and Steinnes 1998; Smith and House 2006; Serow 2001; Stoller and Perzynski 2003). Newbold (1996) examined the behaviors and living preferences of with a cohort of returning and ongoing interstate U.S. migrants in the Older adults tended to leave areas with less access to health care, less aging population, colder climate, and less racial similarities. In regard to migration destination traits, the findings indicate that the most attractive factors included warmer climate, higher proportion of aging population, and more racial similarity (Newbold 1996). The moving rates declined from 8.4% for young old (65–74) to 6.0% for those 75 and older. Individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to move, compared to those with low or middle education levels. Separated, divorced, or widowed people were more inclined to migrate, compared to those still married (Newbold 1996). However, the impact of economic conditions and health status were not analyzed, nor was within-state migration taken into consideration (Newbold 1996).

Socio-Historical Chinese Contexts

Native Chinese who were 50 and over in 2011 have experienced dramatic historical changes in their lives. In the late 1970s, China entered a new stage of development, with economic and social structures started to transform. When the People’s Commune System, an administrative system in rural China, was eliminated, the opportunity for rural individuals to migrate increased, so the flow of rural farmers to urban locations grew at an unprecedented rate (Zhao 2002). Massive investment and supportive policies led to the rapid development of the economy, which led to employment of local labor and created new demand for labor resources (Zhao 2002). In addition, the Hukou system, a household registration system, was revised in 1985 to address the income gap between urban and rural areas, leading to the emergence of “temporary residence permits”, which provided policy support for rural farmers to migrate to cities (Liang et al. 2010).

In recent years, regional development and policy changes resulted in frontier areas welcoming a large number of migrant workers, mainly in mining, smelting, planting, and other resource-based industries, as well as in the urban construction industry. However, compared to Coastal areas, living conditions in frontier provinces were relatively poor, so therefore less attractive to older migrants Possessing more attractive factors, rural workers were less likely to move out of coastal areas making migration and return migration behaviors less visible than central and frontier areas (Zhang and Zhou 2013).

The research on older adults becoming return migrants in China has just begun, examining reasons for both initial and return migration. These migrations occurred both voluntarily and involuntarily. A number of studies support the combined effect of multiple factors that influenced workers to consider whether to return home (Liu 2014; Zhang and Zhou 2013). Some chose to migrate due to increasing needs for medical care associated with aging, while others were forced to move because their residential areas were transformed as part of urban renewal projects (Liu 2014; Tian 2012). Family factors, regional economics, and social welfare differences also influenced the migration situations. Older people tended to move to places with complete medical care and social welfare systems (Chunyu et al. 2013). Family factors, such as providing care for parents or grandchildren tend to be migration motivations among urban older adults (Lu and Song 2006). Adults who are 60 years and older may have parents who are still alive, and it is traditional in China for children to provide care for their aging parents (Zhang and Zhou 2013).

The elimination of migration restrictions in the late 1970s led to a surge of internal migration from rural to urban areas in China (Lu and Song 2006.) This type of migration tends to be temporary and circular, rather than permanent. Experienced farmers went to work in cites during the off seasons, and returned to farm during the busy seasons (Lu and Song 2006; Tong and Piotrowski 2012). Even though the increase of manufacturing industries added many working positions in the central rural areas, it did not prevent interprovincial migration (He & Ye 2014). Further, the Chinese government implemented a unique family planning policy over 30 years ago. Compared to prior generations, the current generation of Chinese elders tends to seek emotional support by moving close to their adult children (Wu 2013). The urban-rural disparity in social welfare also led elders living in rural areas to move to cities (Hu et al. 2011).

Regional income discrepancy was the strongest influence on rural older adults to relocate (Zhang and Zhou 2013). Older migrant workers were more likely to return when working conditions changed (i.e., retirement or dismissal), personal working capacity declined (i.e., could not bear physical labor demands or suffered injuries), family demands occurred (i.e., need to take care of parents or children) or hometown economic conditions improved (i.e., better employment opportunities). Research on the back flow of migrant workers indicates that these factors impact return migration behavior: unemployment, which was the main reason for a large proportion of return migration of rural workers (Chunyu et al. 2013); personal and family issues, which includes needing to care for elderly parents, family marriages and births; housing construction; health condition; and other factors (Murphy 2000; Zhao 2002). For instance, many rural workers returned to their hometowns after they had earned enough to support their children (Wang and Fan 2006; Wang and Yang 2013). Institutional reasons and policy changes are also influencing factors. For instance, the current Hukou system and social security system limit the chances of rural migrant workers to stay in large cities permanently. Rural migrants lack access to health care and their precarious social positions as urban dwellers leaves them few options but to return home if they become ill (Wang, 2006). In addition, employment discrimination against rural migrant workers also leads to returning (Fan 1996). Preferential policies for agricultural work also attract rural migrant workers to return (Fan 1999; Wu 2013; Xu 2010). Older migrants were more likely to intend to return home and have uncertain living preferences, compared to local older residents (Ye and Wu 2016).

Given the above mentioned factors, this study addresses these questions: What are the characteristics of return migrants? What are the factors associated with return migration in later life? What are the geographical patterns of return migration?

Methods

Sample

This data was from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), based on the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The baseline wave of CHARLS was collected in 2011 and included about 10,000 households—17,500 individuals in 28 provinces, 150 counties/districts, and 450 villages/communities. The CHARLS sample is composed of people 45 years and older, living in communities. Four province-level units lack data because the systematical screening methods automatically excluded provinces without enough population, including Tibet, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Hainan. We defined return migrants as individuals that had lived outside of the county/city that they lived before age 16 for at least 6 months and returned home when they were 50 or older. According to the Chinese census, relocating for more than 6 months changes an individuals’ residency. These location changes reflect important social and economic changes in people’s lives with significant ramifications for both the places they leave and those they move to (He and Gober 2003; Zhao 1997).

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 describes the general demographic characteristics of return migrants aged 50 years and older (n = 468; m = 61.6). There were 388 (82.9%) individuals who lived in rural areas and 80 individuals (17.1%) who lived in urban areas in 2011 when they were interviewed. The average return age was 56.5, with an average absence from home of 9.0 years. There were no significant differences between age groups. Compared to all participants aged 50 years and older in CHARLS data, return migrants showed significant gender difference; 339 (72.4%) of the migrants were male, almost three times the number of females (n = 129; 27.6%). It was worth noting that a large percentage (n = 114; 24.4%) were married, but not living with spouses. Fewer return migrants were illiterate, (n = 95; 20.30%) compared to the rest of the participants who were 50 and older (n = 4325; 31.4%), indicating that individuals who migrated from their hometown usually had some, but not a lot, of education.

Table 1.

General demographic characters of return migrants

| Characteristic | Number of all participants 50 + older (%) | Number of return migrants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Urban | 3325 (24.16) | 80(17.09) |

| Rural | 10,438(75.84) | 388(82.91) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6835(49.66) | 339(72.44) |

| Female | 6946(50.47) | 129(27.56) |

| Age | ||

| <60 | 6122(44.48) | 218(46.58) |

| 60–69 | 4742(34.45) | 171(36.54) |

| 70–79 | 2264(16.45) | 67(14.32) |

| > = 80 | 663(4.82) | 12(2.56) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 10,848(78.82) | 296(63.25) |

| Married, not living with spouse | 826(6.00) | 114(24.36) |

| Divorced | 177(1.29) | 7(1.49) |

| Windowed | 1800(13.08) | 47(10.04) |

| Never Married | 132(0.96) | 4(0.85) |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 4325(31.42) | 95(20.30) |

| Primary School | 5573(40.49) | 217(46.37) |

| Middle School | 3242(23.56) | 132(28.21) |

| Vocational School | 353(2.56) | 14(2.99) |

| College and above | 281(2.04) | 10(2.14) |

| Total | 13,763(100.00) | 468(100.00) |

Previous work experience, an important factor that affected people’s returning behavior, is shown in Tables 2 and 3. The majority (63.3%) of the participants in the overall sample (79.6%) worked in agriculture, which reflects the importance of that field in China’s economic structure. However, compared to all the participants who were 50 years and older (13.7% n = 1833), almost 30% of the return migrants (n = 138) had previously worked in other occupations. In addition, 32.6% of the return migrants (n = 44) had previously worked for enterprises, compared to only 26.4% (n = 478) among the total population.

Table 2.

Categories of previous occupations of return migrants

| Category | Number of all participants 50+ (%) | Number of elderly return migrants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-agricultural employees | 1833 (13.7) | 138(29.8) |

| Non-agricultural employers | 687(5.1) | 26(5.6) |

| Household Work | 202(1.5) | 6(1.3) |

| Agricultural Work | 10,651(79.6) | 293(63.3) |

| Total* | 13,373(100.0) | 463(100.0) |

Due to missing data, the total number may be smaller than the total sample size

Table 3.

Types of previous workplace among return migrants

| Type | Total sample (%) | Elder return migrants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Government | 113(6.3) | 5(3.7) |

| Public institution | 215(11.9) | 2(1.5) |

| Nonprofit | 17(0.9) | 0(0) |

| Enterprise | 478(26.4) | 44(32.6) |

| Individual business | 745(41.2) | 62(45.9) |

| Rural cooperation | 87(4.8) | 6(4.4) |

| Household | 62(3.4) | 4(3.0) |

| Others | 93(5.1) | 12(8.9) |

| Total* | 1810(100.00) | 135(100.0) |

Due to missing data, the total number may be smaller than the total sample size

In sum, the majority of return migrants were between the ages of 51–70 years. Compared to the overall sample, about 80% completed at least a primary education, even though level of education above the high school was not significantly different among participants. Most of the return migrants had middle-level average incomes, grew up in rural areas and returned to those communities. The return migrants have a relatively high degree of attachment to their children, have strong family values, and prefer to live with their families.

Statistical Analysis

We used a Binary Logit model for the binary variable of return migration. In preparation for conducting logistic regression, tests for outliers were run, and outliers were corrected or removed. Interviews conducted by others than the selected participants were also removed (questions were answered by other people in the household). In the end, we analyzed 13,763 out of 17,500 observations.

As the subset database from CHARLS is a large dataset consisting of a mixture of different variable types or data outliers, we applied iterative regression imputation, using Stata 14 to account for possible bias due to missing data (Templ, Kowarik, & Filzmoser, 2011). In each step of the iteration, one variable was used as a response variable and the remaining variables served as the regressors. We repeated the procedure until all the missing values were imputed. To adjust for potential bias in the data, we applied multiple imputations for 1725 cases with missing data. Then we conducted descriptive analyses, using Stata 14. When participants answered yes to “have you ever lived outside this county/city for more than 6 months?” it was coded as 1; if they answered no, it was coded as 0. To incorporate the influence of other factors associated with older adults return migration, we examined the influence of housing conditions, living arrangements, community facilities, and geographic attributes. We used a forward selection approach to eliminate the impact of these various factors. Model 1 included the impact of housing conditions. Building on the previous model, Model 2 added living arrangements, and Model 3 added both living arrangements and community facilities. Model 4 added geographic attributes to include all four factors.

Housing Conditions

To assess the housing situation, participants were asked about their housing area (i.e., What is the construction area of your residence?), the number of floors in their house (i.e., Is the building one story or multi-level building?; How many stories?), and whether or not there is an elevator or other accessible facilities (i.e., Are there any handicapped facilities, such as non-stair ramp?). To assess housing infrastructure, participants were asked whether it included water supply, drainage, electricity, heating, ventilation, telephone, and internet connection, with a maximum possible score of 7.

Living Arrangements

An examination of the family living structure was based primarily on older adults’ current living arrangements, within these possibilities: live alone, live only with their spouse, live only with their parents, live only with their children, live with multiple generations or other.

Community Facilities

Our examination of community features included the availability of organizations for older adults and institutions for older-adult care, and the distance to public transportation (i.e., bus/train station) and to a main hospital/clinic. For example, the community questionnaire asked whether there were certain facilities in their community. To evaluate the distance between the community and the main external traffic stops, we asked What is the distance from the village/community office to the most commonly used bus stop if this bus stop locates in this village/community? (answer 0 if this train station locates in this village/community), with the distance measured in kilometers. In addition, participants were asked about the availability of public facilities, such as organizations for helping the older adults and people with disabilities, older adults associations, nursing homes, and exercise and entertainment facilities. Participants responded yes (1) /no (0) as to availability of each specific community facility. Distance to specific community facilities was recorded in kilometers, and used as a continuous variable.

Geographic Attributes

We examined several geographic attributes identified in previous literature to potentially influence older adults return migration. To measure geographical attributes, the community questionnaire asked: terrain (i.e., plains, mountainous region, hills, or plateaus), annual precipitation (i.e., number of rainy or snowy days in 2010), and the annual average temperature differences: What is the main terrain/topography of your village/community?, How many days are rainy days in your village/community for the last calendar year (2010)?, How many days are snowy days in your village/community for the last calendar year (2010)?,and What is the highest and lowest temperature for the last calendar year (2010)?

Geographic Analysis

We categorized participants as either inner- or inter- province migrants. Inner-province migration involved elders who had lived in areas other than their hometown before, but were still in the same province; inter-province migration describes elders who had lived in a different province. To reveal the redistributive effects of population movement, we used the concept of Migration Efficiency (ME), which was created by Plane (1992). McHugh and Gober (1992) extended the concept to specific region-to-region flows. We computed it by dividing the net flow between a pair of provinces by the sum of the gross flow in both directions, multiplied by 100:

where MEijis the efficiency of migration exchange between provinces i and j; FLijand FLji represent the migration flow from province i to province j and from province j to i, respectively. Migration flow efficiency ranges from −100 to +100%. An efficiency value of 100% indicates that all movement is unidirectional, while zero efficiency suggests that equal numbers of migrants are moving in each direction, resulting in no population redistribution between the two provinces (McHugh and Gober 1992).

Results

The geographical analysis provided a general picture of geographic flow of return migration in China. Using the Logit model, we identified the determinants of return behavior, which we assumed to be a combination of cultural, historical, social, and geographical factors, as show in Table 4. We also took into account the role of return migrants’ living preferences.

Table 4.

Logistic regression odds ratio of return migration in later life

| Independent variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Arrangement | OR | 95% Cl | OR | 95% Cl | OR | 95% Cl | OR | 95% Cl |

| Live only with parents | 4.323*** | (4.13, 5.45) | 4.125*** | (4.05, 5.68) | 4.059*** | (4.01, 5.98) | 4.075*** | (3.17, 5.05) |

| Live with multiple generations | 1.328 | (−0.80, 1.62) | 1.317 | (−0.86, 1.93) | 1.323 | (−0.78, 2.02) | 1.320 | (−0.70, 1.82) |

| Alone/only with spouse | 1.351 | (−0.67, 1.92) | 1.315 | (−0.60, 2.02) | 1.283 | (−0.60, 2.54) | 1.285 | (−0.80, 2.02) |

| Live with others | 2.105** | (2.01, 3.21) | 2.070** | (2.00, 3.32) | 1.991** | (1.30, 2.00) | 1.982** | (1.31, 2.05) |

| Live only with childrena | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Physical Health | ||||||||

| No ADL limitation | 0.596 | (−0.20, 0.62) | 0.953 | (−0.53, 1.02) | 0.599 | (−0.37, 0.98) | 0.598 | (−0.89. 1.30) |

| One ADL limitation | 0.555 | (−0.32, 0.70) | 1.695 | (−0.69. 1.73) | 0.578 | (−0.80, 1.03) | 0.580 | (−0.54, 0.73) |

| Two or more ADLs limitationsa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No IADL limitation | 1.375 | (−0.74, 1.52) | 1.409 | (−0.48, 1.97) | 1.340 | (−0.75, 1.79) | 1.323 | (−0.94. 1.92) |

| One IADL limitation | 1.228 | (−0.89. 1.63) | 1.156 | (−0.40, 1.78) | 1.115 | (−0.97. 1.12) | 1.117 | (−0.49. 1.78) |

| Two or more IADLs limitationsa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Self-reported very good or good health condition | 2.551*** | (1.78, 3.60) | 2.577*** | (2.30, 3.40) | 2.671*** | (1.81, 3.47) | 2.681*** | (2.02, 3.35) |

| Self-reported íair health | 1.533 | (−0.50, 1.47) | 1.492 | (−0.51, 1.78) | 1.510 | (−0.47, 1.85) | 1.498 | (−0.53, 1.96) |

| Self-reported poor or very Poor health conditiona | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mental Health | ||||||||

| Very satisfied | 1.125 | (−0.45, 1.87) | 1.287 | (−0.82, 1.47) | 1.271 | (−0.54, 1.98) | 1.248 | (−0.90. 1.74) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 0.760 | (−0.41, 1.08) | 0.791 | (−0.40, 1.07) | 0.760 | (−0.42, 1.05) | 0.758 | (−0.41, 1.02) |

| Not satisfieda | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Housing Condition | ||||||||

| One storey | 0.869 | (−0.40, 1.02) | 0.835 | (−0.40, 1.02) | 0.891 | (−0.40, 1.02) | ||

| More than two storesa | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Good facility condition | 1.278* | (1.04, 3.01) | 1.289* | (1.03, 2.02) | 1.259* | (0.97. 1.58) | ||

| Fair facility condition | 1.164 | (−0.51, 1.72) | 1.171 | (−0.44, 1.45) | 1.149 | (−0.72, 1.84) | ||

| Poor facility conditiona | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Flave elevator | 0.787 | (−0.45, 1.06) | 0.694 | (−0.46, 1.65) | 0.623 | (−0.47, 1.62) | ||

| No elevatora | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Flave accessible facilities | 0.995 | (−0.47, 1.54) | 0.835 | (−0.78, 1.96) | 0.977 | (−0.74, 1.54) | ||

| No accessible facilitiesa | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Community Services | ||||||||

| Flave senior services | 1.122* | (1.11, 2.05) | 1.123* | (1.10, 2.03) | ||||

| No senior servicesa | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Geographic Features | ||||||||

| Terrain-Flills | 1.256 | (−0.94. 1.67) | ||||||

| Terrain-Mountainous region | 1.065 | (−0.85, 1.50) | ||||||

| Terrain-Basin | 1.813* | (1.15, 2.01) | ||||||

| Terrain-Plateau | 0.439* | (0.10, 0.56) | ||||||

| Terrain-Flat areasa | - | - | ||||||

| Log Likelihood | −993.48 | −981.39 | −982.25 | −977.76 | ||||

| Number of Cases | 6943 | 6838 | 6405 | 6253 |

a Designates reference category;

*P < 0.1;

**P < 0.05;

***P < 0.01; CI: Confidence Interval

Geographical Flows of Return Migration

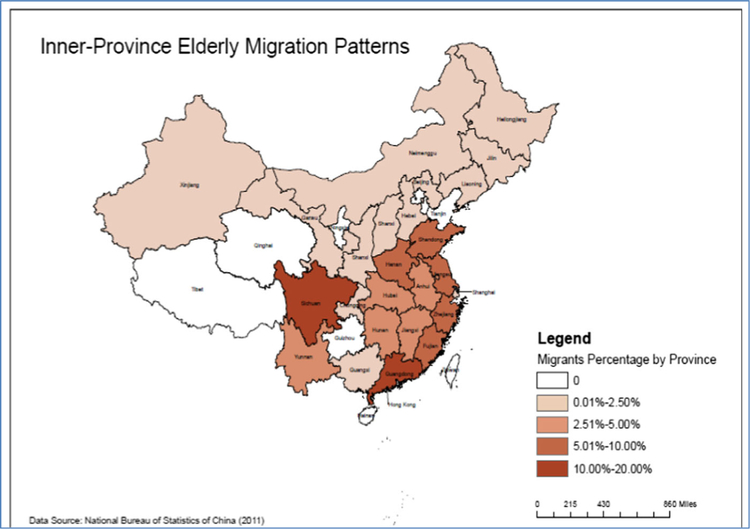

In our study, there were 202 inner-province migrants and 266 inter-province migrants. The original data did not indicate their specific return city, but spatial distributions at the province level reflect mobility of return migrants. We measured migration distribution using the proportion of all migrants in all provinces, which ranged from 0.5 to 19.70%. The spatial distribution pattern is indicated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of inner-province return migrants

We found that most inner-province migration occurred in the south or eastern coast regions, both with thriving economies. Among them, the highest inner-province ratio occurred in Sichuan (19.8%), which included almost one fifth of all the migrants, followed by Guangdong province (13.9%), Fujian (9.4%), Zhejiang (6.9%), Jiangsu (6.93%) and Shandong (5.9%). However, migration in the Central region also occurred, including Henan (6.9%), Jiangxi (4.0%), Hunan (4.0%), Anhui (3.0%), Hubei (3.0%), and Yunnan (3.0%). Provinces in the northern region had a relatively small proportion of inner-province return migrants.

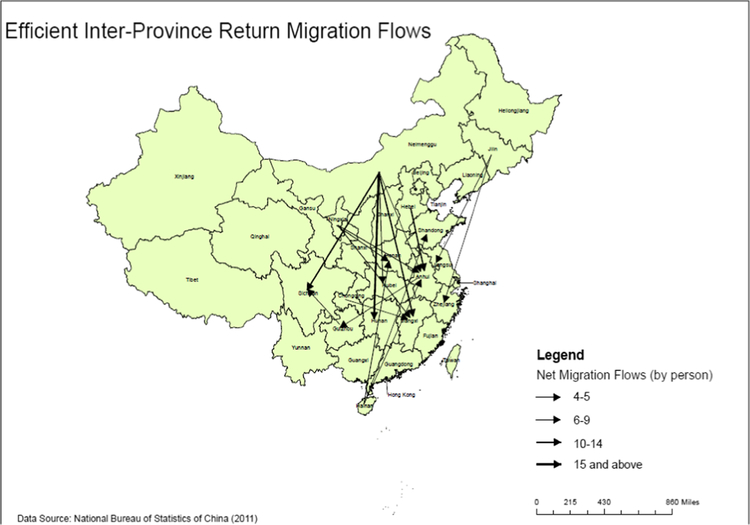

Figure 2 shows geographic flow with enough net migrants, (above 5) and with significant Migration Efficiency (ME>0.75). As indicated on the map, the largest outflow province was Inner Mongolia, followed by the Ningxia, Hainan, and Jilin regions, which experience migrants moving out. Most of the migrants came back to the central region, such as Henan, Anhui, Sichuan, Jiangxi and Hubei. In general, the majority of elder migrants returned from border regions with abundant natural resources and relatively small populations, to the inland agricultural provinces.

Fig. 2.

Efficient inter-province return migration flows

Living Arrangements and Caregiving Roles

The regression results show that there is a significant relationship between return behavior and the need to support parents. Living only with parents was significantly correlated with return migration (p = 0.054 < 0.01); living only with their children (p = 0.375 > 0.01) or multi-generational living (p = 0.388 > 0.01) had no significant impact. This finding may signify a need to be involved in caregiving for either parents or parents-in-law by either the respondents or their spouses. Of the 468 participants, 103 indicated that they were providing care for their parents at the time they were surveyed. The mean age was 58 (SD = 5.485, Age Range 50–72). Care included assisting parents with daily activities, such as performing chores, obtaining groceries and managing finances. While we do not know if they returned home to provide care, the geographical space change may have facilitated the caregiving role.

Housing Conditions

In general, the majority of the houses in rural communities were single-story houses with few multi-story buildings; elevators or accessible facilities were rare. Among the housing indicators, numbers of floors, having an elevator, accessibility of facility, and housing space have no significant influence on older adults return migration. However, the housing infrastructure (p = 0.009 < 0.01) has significant impact on this population.

Community Services

As indicated in Table 4, the distance to transportation stops and distance to medical facilities do not significantly impact return migration. In rural areas, major medical facilities are generally referred to as community health centers (In the CHARLS questionnaire, if there is a community health station in town, then the distance between community and medical facilities is set to 0). Most better equipped and staffed medical facilities were generally located in the town or county relatively distant from rural communities. Therefore, it was hard for return migrants to select migration location based on the proximity to medical facilities. However, within the community organization, “whether there are facilities for senior citizens” (p = 0.012 < 0.1) showed a positive effect (95% confidence intervals).

Geographic Attributes

Different from other types of migration, the geographic terrain has no significant influence on return migration. Annual precipitation (p = 0.003 < 0.01) is positively related to return migration and annual temperature difference (p = 0.000 < 0.01) is negatively related, indicating that these migrants tend to move to places with higher annual precipitation and lower annual temperature differences.

Discussion

This paper gives reasons for relocation that are interpersonal. Unlike gerontological models of relocation discussing self-interest (amenity moves) or moves toward kin to receive care from them, we found that possibilities of productive aging may influence (e.g., caregiving) older adults’ return migration. The main motivations include providing care for their parents, access to improved living conditions, preference of the harmonious and familiar living community, and more habitable natural environments. In conclusion, many older people have a desire of “returning to their roots,” whether the impetus is due to family structure or geographical and social living environments.

Family Structure

Traditional Chinese society is a clan kinship society, with family as the basic organizational unit. The most important concept is maintenance of a harmonious family, or filial piety. Our analysis shows that the majority are migrant workers who return home, and their average age is lower than the average retirement age among urban residents. Away from home for an average of nine years, those from rural areas defied the old traditional Chinese belief of “no travel far away when parents are alive” and moved to large cities to obtain greater resources. Consequently, individuals may feel worried or guilty about leaving their aging parents at home (Liang et al. 2010; Lu and Song 2006). Filial culture has a strong internal impetus for the studied population. When their parents were old or in need of care, returning home becomes the only option, since there is a lack of facilities and services for older adults in rural communities. We found that people living with their parents only are more likely to be caregivers and people living with children only are more likely to be care recipients; multi-generational families reflect the diversity of family care and provision structure, while living alone or only with their spouses reflect the “empty nest” syndrome common in modern society.

Geographical and Social Living Environment

The findings indicated that return migrants tend to move to places with higher annual precipitation and lower annual temperature, compared to their original locations. Considering how many return migrants seek agricultural work, that move seems logical, since most plants need high annual precipitation and lower annual temperatures. In addition, compared to environments in big cities, this type of environment is more habitable, so older adults are more likely to migrate there. Even though these persons lived outside of their hometown for a while, they may still have a strong sense of attachment to their hometown and its environment. The sense of familiarity may reinforce a sense of belonging. In addition, the need for ease of transportation for external connection among older adults returned to rural areas from urban cities was not high, as they were in the age group who were less likely to migrate.

Limitations

First, the study is limited by the age range of both middle-age and older adults included in the study. Thus, reasons for return migration may differ by cohort effect as well as by geography. Second, this survey approach only captured binary answers to some of the most interesting parts of this investigation, even though CHARLS is a database with a comprehensive questionnaire, specific and detailed questions about life experiences after relocation are not included. We were not able to capture details about what the experience was like to create a new life in a familiar place and provide care to kin after living so many years away. Last, we need more information about the particular experiences of the subgroups identified: those who migrated from the coastal areas and those who migrated from the frontier (boarder regions of China).

Future researchers could conduct a qualitative study with interviews and observations to follow up and explore experiences and life quality after return migration. In addition, researchers could explore how older return migrants’ needs are met, specifically inquiring about social welfare, housing conditions, and community facilities and services. The CHARLS data has been collected every other year since 2011; thus future longitudinal research could study the physical and cognitive health trajectories and compare/contrast the experiences of older migrants, return migrants and non-migrants.

Implications and Conclusions

As people age, chronic illnesses and declining physical functions will increase the need for community services and facilities. Community-based, long-term care services and supports are an integral part of elder care. Integrated community services not only reduce relocation among older adults, but can also help older adults who migrated adapt to a new environment more smoothly (Chunyu et al. 2013; Reichert et al. 2014). Policy should focus on care services for these migrants to help them re-establish formal or informal social networks in their hometowns, if they are returning and assuming caregiving roles or needing services for themselves in the future.

In recent years, policies and programs like New Rural Community Building, Home Replacement, and Farmer Upstairs have been launched to change the living style of some rural communities. In addition, most of the return migrants were in good health when they moved, so accessibility features were not required (e.g., elevators) because of single level housing. However, differences between rural housing and urban housing exist. For example, in rural settings, because the community is wide-ranging, as is the population, the cost of building facilities and providing services tends to be higher than in urban areas. Most rural communities only have centralized power and telecommunications, with water, gas, and heat supply provided by the individual community. In some areas, individual households need to provide them individually, through the use of water wells or burning stoves. Drainage and waste disposal systems are not well constructed and universal access to the Internet is not always available.

The different infrastructure experienced in rural communities was a considerable challenge for long-term older migrant workers who had adapted to the urban life. They might not be able to take on rigorous physical tasks as they could when they were younger. The higher the level of infrastructure in their home communities, the easier for the older adults to adapt upon returning, and when they wanted to return home, the easier it would be for them decide to do so.

The strong cultural tradition assures that families will continue to serve as the main support for older adults in China. However, it is important to explore and create innovative, comprehensive and diverse ways of providing elder care especially in the central regions, where the percentage of return older migrants is high. Community amenities, such as social services, health services, and recreational facilities are important means for increasing community livability and influencing peoples’ feelings of attachment. Our findings affirm that stronger incentives to return home include improved care and residential communities. To serve the older return migrants in regions where mobility and migration rates are high, public service facilities and social security systems should be improved.

The proportion of older return migrants in the overall population is relatively low. However, with the accelerated aging process, urban and rural construction and industrial restructuring, the number of older return migrants will undoubtedly increase and this will impact economic and social development. Thus, understanding the factors influencing the flow of return migration among elders will positively affect the promotion of social development, service delivery, and increased living standards of rural older adults.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the comments and contribution of Dr. Jon Pynoos, Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California; Dr. Changchun Feng, School of Urban and Environmental Science, Peking University, Beijing; Dr. Karen A. Roberto, Center for Gerontology Virginia Tech; Raven H. Weaver, PhD candidate. Center for Gerontology Virginia Tech; The Wayne State University Institute of Gerontology, the National Institutes of Health, P30 AG015281, and the Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biography

Yujun Liu is a postdoctoral fellow at Department of Psychology at Brandeis University. She got her PhD in Human Development with a simultaneous degree in MPH from Virginia Tech. She holds a Master of Social Work from Washington University in St. Louis. Yujun’s research interests include community services for older adults, healthy aging, and family caregiving.

Xiaolu Dou got her PhD in human geography, School of Urban and Environment, Peking University (PKU), Beijing, China. She is a lecturer of Capital University of Economics and Business in Beijing, China and the research director of Beijing Bridata Technology co.,Ltd. She was a visiting scholar in Davis school of gerontology, university of Southern California. She was a research assistant in center of real estate research and appraisal in PKU. Her research interests include urban and regional development, elderly housing, migration and urban policy.

Tam E. Perry is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at Wayne State University. She received her PhD in Social Work and Anthropology from the University of Michigan. Her ethnographic research addresses housing transitions of older adults from a network perspective. As health, mobility and kin and peer networks alter, she explores how older adults contemplate their homes and its contents. She studies housing transitions because, while aging in place is often preferred and cost-effective, inevitably some older adults will undertake the emotional and physical labor, as well as the negotiation of medical, financial and long-term care infrastructures, involved in relocation. Her research has been supported by the National Institute on Aging, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the University of Michigan and Wayne State University.

Footnotes

Conflict Interests Yujun Liu declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Xiaolu Dou declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Tam E. Perry declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained by the CHARLS database researchers from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Treatment of Experimental Subjects (Animal and Human) This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Yujun Liu, Email: lyujun@brandeis.edu.

Xiaolu Dou, Email: selphie.dou@gmail.com.

Tam E. Perry, Email: teperry@wayne.edu.

References

- Chunyu MD, Liang Z, & Wu Y (2013). Interprovincial return migration in China: Individual and contextual determinants in Sichuan province in the 1990s. Environment and Planning A, 45, 2939– 2958. 10.1068/a45360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KS, & Rork JC (2010). “Going with the flow”—A comparison of interstate older adults migration during 1970–2000 using the (I) PUMS versus full census data. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B, 767–771. 10.1093/geronb/gbp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown WH (1988). State economic implications of older adults interstate migration. The Gerontologist, 28,533–539. 10.1093/geront/28.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou X, & Liu Y (2015). Elderly migration patterns in China: Types, patterns and determinants. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 6, 1–21. 10.1177/0733464815587966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustmann C (1997). Return migration, uncertainty and precautionary savings. Journal of Development Economics, 52, 295–316 Retrieved from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpb21/Cpapers/returnmigrationun.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(1), 1–12. 10.2307/1132065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C (1996). Economic opportunities and internal migration: A case study of Guangdong province, China. The Professional Geographer, 48, 28–45. 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1996.00028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C (1999). Migration in a socialist transitional economy: Heterogeneity, socioeconomic and spatial characteristics of migrants in China and Guangdong Province. International Migration Review, 33(4), 954–987. 10.2307/2547359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubernskaya Z (2015). Age at migration and self-rated health trajectories after age 50: Understanding the older immigrant health paradox. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 279–290. 10.1093/geronb/gbu049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas WH, Bradley DE, Longino CF, Stoller EP, & Serow WJ (2006). In retirement migration, who counts? A methodological question with economic policy implications. The Gerontologist, 46, 815–820. 10.1093/geront/46.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, & Gober P (2003). Gendering interprovincial migration in China. International Migration Review, 11, 1220–1251. 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00176.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He C, & Ye J (2014). Lonely sunsets: Impacts of rural-urban migration on the left-behind elderly in rural China. Population, Space and Place, 20, 352–369. 10.1002/psp.1829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan TD, & Steinnes DN (1998). A logistic model of the seasonal migration decision for older adults households in Arizona and Minnesota. The Gerontologist, 38, 152–158. 10.1093/geront/38.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Xu Z, & Chen Y (2011). Circular migration, or permanent stay? Evidencefrom China’s rural-urban migration. China Economic Review, 22, 64–74. 10.1016/j.chieco.2010.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M (1980). Housing the elderly: Residential quality and residential satisfaction. Research on Aging, 2, 309–328. 10.1177/016402758023002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Li J, & Ma Z (2010). Migration and remittances in rural China. Population Association of America, 1–19 Retrieved from http://paa2010.princeton.edu/papers/100874. [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E, & Longino CF Jr. (1987). Migration patterns among the older adults: A developmental perspective. The Gerontologist, 27, 266–272. 10.1093/geront/27.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J (2014). Ageing, migration and familial support in rural China. Geoforum, 51, 305–312. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, & Song S (2006). Rural urban migration and wage determination: The case of Tianjin, China. China Economic Review, 17, 337–345. 10.1016/j.chieco.2006.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, & Eschbach K (2005). Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(Special Issue 2), S68–S75. 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh K, & Gober P (1992). Short-term dynamics of the U.S. interstate migration system, 1980–1988. Growth And Change, 23, 428–445. 10.1111/j.1468-2257.1992.tb00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R (2000). Return migration, entrepreneurship and local state corporatism in rural China: The experience of two counties in South Jiangxi. Journal of Contemporary China, 9, 231–247. 10.1080/713675936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold KB (1996). Determinants of older adults interstate migration in the United States, 1985–1990. Research on Aging, 18, 451–476. 10.1177/0164027596184004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold KB (1999). Spatial distribution and redistribution of immigrants in the metropolitan United States, 1980 and 1990. Economic Geography, 75(3), 254–271. 10.1111/j.1944-8287.1999.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelaniuk I (2005). Best practices to manage migration: China. International Migration, 43, 189–206. 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry TE (2014). Moving as a gift: Relocation in older adulthood. Journal of Aging Studies, 31, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry T (2015). Make mine home: Spatial modification with functional implications in older adulthood. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 453–461. 10.1093/geronb/gbu059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry TE, Andersen TC, & Kaplan DB (2013). Relocation remembered: Perspectives on senior transitions in the living environment. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 75–81. 10.1093/geront/gnt070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane D (1992). Age-composition change and the geographical dynamics of interregional migration in the U.S. Annuals of the Association of American Geographers, 82(1), 64–85 Retrieve from http://district.bluegrass.kctcs.edu/clovis.perry/GEO_172/Chapter_3/Age-Composition_Change_and_the_Geographical_Dynamics_of_Interegional_Migration_in_the_US.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert C, Cromartie JB, & Arthun RO (2014). Impacts of return migration on rural U.S. communities. Rural Sociology, 79, 200–226. 10.1111/ruso.12024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles GD, & Watkins JF (2003). History, habit, heart and hearth: On making spaces into places In Schaie KW, Wahl H-W, Mollenkopf H, & Oswald F (Eds.), Aging independently: Living arrangements and mobility, 77–96. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Serow WJ (2001). Retirement migration counties in the southeastern United States: Geographic, demographic, and economic correlates. The Gerontologist, 41, 220–228. 10.1093/geront/41.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, & House M (2006). Snowbirds, sunbirds, and stayers: Seasonal migration of older adults adults in Florida. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S232– S239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speare A, Avery R, & Lawton L (1991). Disability, residential mobility, and changes in living arrangements. Journal of Gerontology, 46, S133–S142. 10.1093/geronj/46.3.S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark O, & Taylor JE (1989). Relative deprivation and international migration. Demography, 26, 1–14. 10.2307/2061490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark O, & Taylor JE (1991). Migration incentives, migration types: The role of relative deprivation. The Economic Journal, 101, 1163–1178 Retrieved from http://down.cenet.org.cn/upfile/43/2006119215845104.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller EP, & Longino CF (2001). “Going home” or “leaving home”? The impact of person and place ties on anticipated counterstream migration. The Gerontologist, 41, 96–102. 10.1093/geront/41.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller EP, & Perzynski AT (2003). The impact of ethnic involvement and migration patterns on long-term care plans among retired sunbelt migrants: Plans for nursing home placement. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, S369–S376. 10.1093/geronb/58.6.S369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templ M, Kowarik A, & Filzmoser P (2011). Iterative stepwise regression imputation using standard and robust methods. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 55(10), 2793–2806. [Google Scholar]

- Tian M (2012). Children’s migration decisions and elderly support in China: Evidences from CHARLS pilot data. Front Economics China, 7, 122–140. 10.3868/s060-001-012-0006-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, & Piotrowski M (2012). Migration and health selectivity in the context of internal migration in China, 1997–2009. Population Research and Policy Review, 31, 497–543. 10.1007/s11113-012-9240-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters WH (2002). Later-life migration in the United States: A review of recent research. Journal of Planning Literature, 17, 37–66. 10.1177/088541220201700103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, & Fan C (2006). Success or failure: Selectivity and reasons of return migration in Sichuan and Anhui, China. Environment and Planning A, 38, 939–958. 10.1068/a37428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, & Yang W (2013). Self-employment or wage-employment? On the occupational choice of return migration in rural China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 5, 231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RF (1980). Why older people move: Theoretical issues. Research on Aging, 2, 141–154. 10.1177/016402758022003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RF, & Roseman CC (1979). A typology of older adults migration based on the decision making process. Economic Geography, 55(4), 324–337 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/143164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y (2013). One-child policy and older adults migration. Sociology Study, 4, 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H (2010). Return migration, occupational change, and self-employment. China Perspectives, 4, 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, & Wu X (2016). Location preference in migration decision: Evidence from 2013 China household finance survey. The Chinese Economy, 49(5), 359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, & Zhou S (2013). An analysis of the migration selectivity of the elderly in China. South China Population, 3, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y (1997). Labor migration and returns to rural education in China. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79, 1278–1287. 10.2307/1244284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y (2002). Causes and consequences of return migration: Recent evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 30, 376–394. 10.1006/jcec.2002.1781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]