Abstract

Internalizing symptoms are prevalent in students as they enter and complete college. Considering research suggesting mental health benefits of pet ownership, this study explores the relationship between pet ownership, social support (SS), and internalizing symptoms (IS) in a cohort of students across their 4-year college experience. With no differences at college entry, students growing up with pets had greater IS through the fourth year, and greater SS through the third year, than those without pets. Currently living with a pet, gender, SS and personality predicted IS in the fourth year. Females experiencing higher IS in their first year are more likely to live with pets in their fourth year, and fourth year females living with pets or greatly missing absent pets have higher IS than females without pets or missing pets less. Findings suggest a unique relationship between IS in female students and their pet relationships not seen in males.

Keywords: pet ownership, college student mental health, internalizing symptoms

Going to college represents a significant developmental milestone, but college students face a unique set of environmental pressures and socio-developmental context (Evans, Fomey, Guido, Renn, & Patton, 2010). The transition to college and navigating in a collegiate setting often involve significant stress associated with increased academic demands and expectations, leaving home and adjusting to new environments, establishing new peer groups and social support networks, and physical separation from family and friends (e.g., Grace, 1997; Jackson & Finney, 2002; Ross, Niebling, & Heckert, 1999). College students are thus at heightened risk for elevated emotional distress and mental health challenges (American College Health Association, 2017).

Large-scale national surveys document the prevalence of depression and anxiety in college age adults. The 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates 10.3% of college age (age 18–25) adults in the United States experienced a major depressive episode in the previous 12 months (SAMHSA, 2015). Similar results were found in an analysis of college-age (19–25) adults interviewed in the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (Blanco et al., 2008). The past-year prevalence rates of a mood disorder and an anxiety disorder among college students were 10.62% and 11.94%, respectively. Combining anxiety and depressive disorders, a randomized web survey at one university reported slightly higher prevalence rates of these internalizing disorders at 15.6% for undergraduates and 13.0% for graduate students (Eisenberg, Gollust, Golberstein, & Hefner, 2007).

Although these studies assessed anxiety and depression disorders in college age students, higher prevalence rates are reported from studies assessing anxiety and depression symptoms. The 2015 National College Health Assessment results reveal that 56.9% of college students felt overwhelming anxiety at some point during the previous 12 months and 34.5% felt so depressed that it was difficult to function (ACHA, 2015). Based on scores on the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, a university based study reported 15% of students were experiencing severe or extremely severe anxiety, 10% experiencing moderate anxiety, and 15% mild anxiety (Beiter et al., 2015). Depression scores revealed 11% of students were experiencing severe or extremely severe depression, 12% experiencing moderate depression, and 10% mild depression.

It is well recognized that internalizing symptoms of depression and anxiety negatively impact college students and interfere with college success and quality of life (Beiter et al., 2015; Brandy, Penckofer, Solari-Twadell, & Velsor-Friedrich, 2015). The prevalence of these internalizing symptoms in college students highlights the importance of identifying factors that mitigate these symptoms.

Lower levels of depression and anxiety in college students are associated with higher levels of social support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). Higher social support in college students has been associated with decreased depression in several studies (Brandy et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2014). Further, social support is recognized as moderating the impact of stressful events on physiological and psychological outcomes (Bonas, McNicholas, & Collis, 2000; Friedmann, Thomas, & Son, 2011; Grav, Hellzèn, Romild, & Stordal, 2012; Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004).

Pet Ownership and Social Support

Social support theory posits that social support buffers the impact of stressful events, thereby contributing to well-being (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Pets are considered by some as a form of social support (Allen, Blascovich, Tomaka, & Kelsey, 1991; McCune et al., 2014) and social support theory has been proposed as one theory explaining beneficial effects of human-animal interaction (Beetz, 2017). Human-pet relationships are reported to 1) be similar to human-human relationships (Bonas, McNicholas, & Collas, 2000), 2) provide a stable source of attachment security (Beck & Madresh, 2008), and 3) embody emotional closeness equivalent to close family relationships; (Barker & Barker, 1988; Cain, 1985). An early study found that dog owners were as emotionally close to their pet dogs as to their closest family member (Barker & Barker, 1988). The pet’s close place in the family is also supported in results of a national survey of military families, with 68% of respondents indicating pets are considered full family members (Cain, 2008). A recent study extended this area of inquiry to college students with findings consistent with the original Barker & Barker study. Using the same assessment strategy, investigators found students were as close to their pets as to their closest family member with 43% closer to their pet than to any family member (Barker, Barker, McCain & Schubert, 2017). Many students are separated from their pets while attending college and it is unknown how this separation may contribute to anxiety and depression in college students.

Any benefit of social support provided by pets may or may not extend to lessening symptoms of anxiety and depression. Studies of the relationship between pet ownership and depression have yielded mixed results. Some studies associate pet ownership with lower depression (in single women; Tower, 2006), less loneliness (Stanley, Conwell, Bowen, & Van Orden, 2014), and enhanced well-being (Cline, 2010), although others report increased depression in pet owners (in unmarried men; Tower, 2006). Similarly, pet attachment in older women has been both positively associated with depression (Miltiades & Shearer, 2011) and also with mediating the relationship between loneliness and depression (Krause-Parello, 2012; Miltiades & Shearer, 2011). The causal factors driving the mixed results in these correlational studies are unclear. Females who are lonely or depressed may acquire pets for companionship and comfort or some unobserved variable associated with pet ownership may account for levels of depression. The mixed findings may also be explained by methodological differences in these studies.

Several studies suggest that childhood pets provide a form of social support for children (Van Houtte & Jarvis, 1995). Children are reported to be emotionally close to their pets (Barker & Barker, 1988; Vidovic, Stetic, & Bratko, 1999) and to view their pets as companions and confidants (Melson, Peet, & Sparks, 1991; Vidovic et al., 1999), potentially providing a complement or substitute for other relationships (Van Houtte & Jarvis, 1995). Although not conclusive, some studies report benefits of growing up with pets, including increased empathy, self-esteem, self-concept, prosocial orientation, social competence, autonomy and less loneliness, particularly for children with higher attachment to pets (Barker & Wolen, 2008; Daly & Morton, 2006; Melson et al., 1991; Purewal, Christley, Kordas, Joinson, Meints, Gee & Westgarth, 2017; Van Houtte & Jarvis, 1995; Vidovic et al., 1999). Recent research lends further support in finding childhood pet ownership associated with decreased childhood anxiety (Gadomski et al., 2015) and pet attachment associated with adaptive coping strategies in children facing a major stressor, family member deployment (Mueller & Callina, 2014).

However, it is largely unknown how growing up with a pet may affect children as they mature and leave home. As pets are increasingly seen as family members (Barker & Barker, 1988; Cain, 1985) and a form of social support, this new focus of research is appropriate and important, given the potential stress associated with being away from family members while attending college and changes in social support. There is a gap in the literature, largely due to cross-sectional studies of benefits of pet ownership for adults, without controlling for previous pet ownership (Podberscek & Gosling, 2000), and cross-sectional studies of pet ownership in children (Purewal, et al., 2017). Little research exists on the effect of growing up with a pet on college students. One study of undergraduates found those who grew up with dogs and/or cats had lower distress and higher social skills than those growing up without dogs (Daly & Morton, 2009). Another study looked at internalizing symptoms in college students with a focus on the relationship between childhood pet attachment and exposure to pet aggression on internalizing symptoms (Girardi & Pozzulo, 2015). Significant relationships were only found for those with medium attachment levels, but not those with high or low attachment levels. Students with medium levels of childhood pet attachment who were exposed to pet aggression had higher internalizing symptoms than those not exposed. Students with medium attachment levels who were not exposed to aggression had lower internalizing symptoms that those with low attachment levels.

The aim of the current study was to build on prior research and to investigate the relationship between pet ownership, social support, and internalizing symptoms in a cohort of students as they enter college and through their 4-year college experience. Focusing on this developmental period is important as college students face a host of unique challenges and elevated levels of stress associated with their increased autonomy and responsibilities, and new social roles. Specifically, we explore 1) the relationship between growing up with a pet, social support, and internalizing symptoms through the 4 year college experience, 2) the relationship between currently living with a pet, social support, and internalizing symptoms, and 3) pet ownership variables as predictors of internalizing symptoms. In addition to addressing the gap in existing research, this study responds to a recent critical review of human-animal interaction research calling for the inclusion of pet questions in large health surveys and conducting longitudinal studies to address limitations resulting from small samples and cross-sectional studies relying on a single measurement time (McCune et al., 2014).

This study included pet ownership related questions in a multi-year, university-wide survey on substance use and mental health outcomes. Existing survey items enabled the examination of internalizing symptoms and social support across the four years of college as well as potential covariates represented by personality and gender. Personality and gender were considered as potential covariates, given evidence that these variables may differ between pet owners and non-owners and also be associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Personality is assessed in the context of the first college year and not as a consistent trait. Studies document the lack of consistency in personality characteristics over context and time (Caspi & Roberts, 2001; Lewis, 2001). However, since several studies note differences in personality characteristics and gender associated with pet owners and pet attachment (Cline, 2010; Gosling & Bonnenburg, 1998; Gosling, Sandy, & Potter, 2010; Herzog, 2007; Podberscek & Gosling, 2000; Westgarth et al., 2010), it is important to consider this potential covariate. Also, differences in personality characteristics and social support have been associated with depression and anxiety (Bienvenu et al., 2004; Brandy et al., 2015; Davidson, Begley, & Amari, 2012; Grav et al., 2012; Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Stice et al., 2004). Therefore, we used personality as assessed in Year 1 as a best estimate of personality to contribute to the discussion of the relationship between pet ownership and internalizing symptoms and inform the design of future studies.

Methods

Background

The study took place at a mid-Atlantic, urban university in the United States. Data collection was part of a university-wide, research project, “Spit for Science” (S4S). The project’s purpose was to investigate the effect of genetic, developmental, and environmental factors on substance use and mental health outcomes across time (Dick et al., 2014). Students were invited to participate in an online survey as they enter their first year of college, with follow-up surveys in spring of their first, second, third, and fourth years. Surveys were administered through the university’s REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Harris et al., 2009) system, a secure web-based system. Students were offered $10 and a S4S themed tee-shirt for survey completion. Students completing the initial survey were invited to provide saliva samples for DNA analysis and provided an additional $10 for doing so. Participation rate for the freshman year was 68% (n=2715), much higher participation than similar U.S. studies and survey participants were found to be representative of the gender and racial/ethnic distribution of the underlying study body (Dick, et al., 2014).

Social activities promoting S4S were held on campus as were educational forums educating students about mental health and substance abuse and identifying available campus resources. Flyers providing summaries of survey results were disseminated widely through various outlets and posted in common student areas, including restroom stalls. All materials included contact information for campus counseling resources.

Survey participation rates varied year-to-year for the student cohort enrolling in Year 1 with 57.5% participating in the spring survey in Year 1, 49.6% in Year 2, 36.5% in Year 3, and 32.2% in Year 4.

The S4S survey included a broad range of items to assess mental health, alcohol and substance use outcomes as well as related protection and risk factors. The authors were initially able to include brief items on growing up with pet and pet attachment in the second year survey with brief follow-up items on currently living with a pet and missing a pet included in the fourth year survey.

Participants

Study participants included the cohort of 466 males and 865 female students who completed the pet ownership items on the S4S second year survey. Although gender of all S4S survey participants were representative of the underlying student body, in this pet ownership study, female participation (65%) was overrepresented compared with the overall student body (57%). The average age of participants was 18.47 in the first year with ages ranging from 18 to 20.6. For those students reporting ethnicity, a slight majority of students were non-white (53%, n=696) with 22% African-American, 18% Asian, 13% other races or combination of races, and 47% white. Twelve students did not respond. The percentage of white and non-white participation is identical to the overall student body.

Measures

Except for the addition of six pet-related items, all other measures were part of the existing S4S survey.

Internalizing Symptoms.

A subset of anxiety and depression scale items from the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90, Derogatis, Lipman, & Covi, 1977) were included in the fall and spring surveys. The SCL-90 is a widely used 90-item self-report symptom inventory with validity and reliability well established (Derogatis & Cleary, 1977; Derogatis et al., 1977; Derogatis, Rickels, & Rock, 1976). Empirically derived items from the anxiety and depression subscales were included in the surveys using a past month timeframe with response options ranging from “1=not at all” to “5=extremely”. Average responses from those with complete responses to over half of the items were used to create anxiety (α=0.85) and depression (α=0.89) subscales. For this study, four items were used for anxiety (fall α=0.82, spring α=0.84) and four for depression (fall α=0.80, spring α=0.82) with Cronbach’s alphas calculated from first year fall and spring surveys. Because of the high comorbidity between anxiety and depression (Nottelmann & Jensen, 1995) with comorbidity rates reported to be as high as 70% (Zahn–Waxler, Klimes–Dougan, & Slattery, 2000), scores on the two scales were combined in this study to provide a measure of internalizing symptoms. Prior factor analysis provides additional rationale for combining these scales (Achenbach, 1991).

Personality.

The Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999) was included in the fall survey of Year 1 to assess personality. The BFI has five subscales measuring Openness (α=0.74), Agreeableness (α=0.76), Extraversion (α=0.84), Conscientiousness (α=0.79), and Neuroticism (α=0.81). Test-retest reliabilities for the 44-item inventory range from 0.80 to 0.90 with strong convergent and divergent validity (John & Srivastava, 1999). Five response options range from “disagree strongly” to “agree strongly”. Cronbach’s alphas in our sample ranged from 0.63 for agreeableness to 0.79 for extraversion.

Social Support.

Three social support subscales from the RAND Medical Outcomes Study (Hays, Sherbourne, & Mazel, 1995), were adapted for the S4S survey (Dick et al., 2014). Empirical evidence supports the reliability and validity of this scale (Shelbourne & Stewart, 1991). One item assesses each of the dimensions of emotional/informational support, positive social support, and availability for confiding with responses summed for a total score. Participants indicate how often (“one, some, most, or all of the time”) someone was available to 1) give good advice about a crisis 2) get together with for relaxation, and 3) confide in or talk about your problems. Cronbach’s alphas for this study were 0.83 (first year fall) and 0.84 (first year spring).

Pet Ownership.

In order to explore the relationship between pet ownership, social support, and internalizing symptoms, we were permitted to include brief items consistent with the existing item format in the S4S Survey. In the second year survey, growing up with a pet was assessed by three questions with “yes” and “no” response options: “Did you grow up with a dog?”, “Did you grow up with a cat?”, and “Did you grow up with another pet?” These items were selected to control for potential outcome differences by species of pet. Since level of attachment to a pet may moderate any effect of pet ownership, a subsequent question for those responding affirmatively to the pet ownership item assessed pet attachment: “How attached were you to your favorite pet(s)?” using a visual analog scale with response anchors of “0 = Not at all attached”, “50 = moderately attached”, and “100 = extremely attached”. Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

The S4S survey length prohibited inclusion of a published pet attachment scale, however, single item scales are widely used in clinical research and have been used to assess many psychological outcomes, including attachment style (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003). Single item measures are a viable means of collecting data for constructs that are universally understood with little ambiguity and their psychometrics have been empirically supported for measuring many constructs including, self-esteem (Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001), job satisfaction (Wanous & Reichers, 1996), symptom severity, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life (Zimmerman et al., 2006), anxiety (Barker, Pandurangi & Best, 2003), feelings (Aitken, 1969), and mood (Ahearn, 1997).

After a preliminary analysis of first year data suggested increased internalizing symptoms in students who grew up with a pet, we were interested in determining the potential confound of currently living with pets. We were permitted to add two additional questions to the fourth year survey to probe current pet ownership and level of missing a pet for students not living with their pets. Living with a pet was assessed by one question: “If you own a pet, is it currently living with you?” with response options of “yes” and “no”. For those owning, but not living with a pet, a subsequent question assessed missing a pet: “How much do you miss your pet?” using a visual analog scale with response anchors of “0 = Not at all”, “50 = moderately”, and “100 = extremely”. Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

Visual Analog Scales have been successfully used in human-animal interaction research with empirically-based support for the validity and reliability of these scales. (Barker, Knisely, McCain & Best, 2005; Barker, Knisely, McCain, Schubert, & Pandurangi, 2010; Barker, Pandurangi & Best, 2003). The six pet ownership items included in the survey are listed in the Appendix.

Demographics.

Existing survey items on gender and race were assessed by single items. Gender response options were “male” and “female” Race response options were: “American Indian/Alaskan Native”, “Asian”, Black/African American”, “Hispanic/Latino”, “More than one race”, “Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”, “Unknown”, and “White”. All survey items included a response option of “I choose not to answer”.

Procedures

The study design and procedures were approved by the senior author’s university Institutional Review Board. Incoming first year students and their parents were informed of the S4S survey two weeks before the fall semester through mailed letters. The week before classes began, an invitation to participate, with a link to the online informed consent and survey, was sent to the university email of all incoming first year students ages 18 and older. Procedures for the spring follow-up surveys were the same as for the initial first year fall survey with letters mailed followed by emailed invitations mid-semester for first, second, third, and fourth years.

Data Analysis

Analysis was conducted on the four year survey responses of the cohort of students who answered the childhood pet questions in the second year. Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic variables. Cronbach’s alphas were computed for all measures. Following an analysis of variance showing no significant differences on internalizing symptoms in the first year by pet species, pet ownership was treated as a categorical independent variable, combining pet species into those who answered “yes” to growing up with a pet versus those who answered “no.”

Initial independent t-tests were used to explore trends in internalizing symptoms, personality, and social support by growing up with a pet. A fixed regression model was used to examine simultaneously the effects of three possible predictor variables (currently living with a pet (yes/no), having grown up with a pet (yes/no), and the interaction between the two, in addition to possible covariates of gender, personality, and social support on internalizing symptoms in the fourth year. Stepwise procedures were used to create a parsimonious model for internalizing symptoms, removing covariates which were not statistically significant. Model R2 values and partial R2 values were computed to determine the relative contribution of each variable to the total explained variance.

This follow-up design, rather than a longitudinal design, was used in the data analysis for several reasons. First, the original S4S study was designed as a follow-up study, tracking cohorts over four years of higher education and allowing new individuals to join and to leave (not respond) in each year. As such, the study was designed to observe outcomes on students for each year of education as a whole and not designed to solely monitor specific individuals responding in the first year. Our use of the follow-up design is meant to replicate the design of the larger study. Second, we were not able to include a question about whether or not the student is currently living with their pet until year 4 of the study. Therefore, the influence of living with a pet or missing the pet could not be discerned until year 4. Although we can, and did, look at the influence of growing up with a pet across all 4 years, we are not able to model individual trajectories for internalizing symptoms across all 4 years while adjusting for the possibly time-varying influence of living with a pet, or further, missing a pet. The most comprehensive information with respect to current pet influence occurs only in year 4 when this information was collected and thus a follow-up analysis was conducted.

All analyses were conducted using SASv9.3 and statistical procedures using a type I error rate of 0.05.

Results

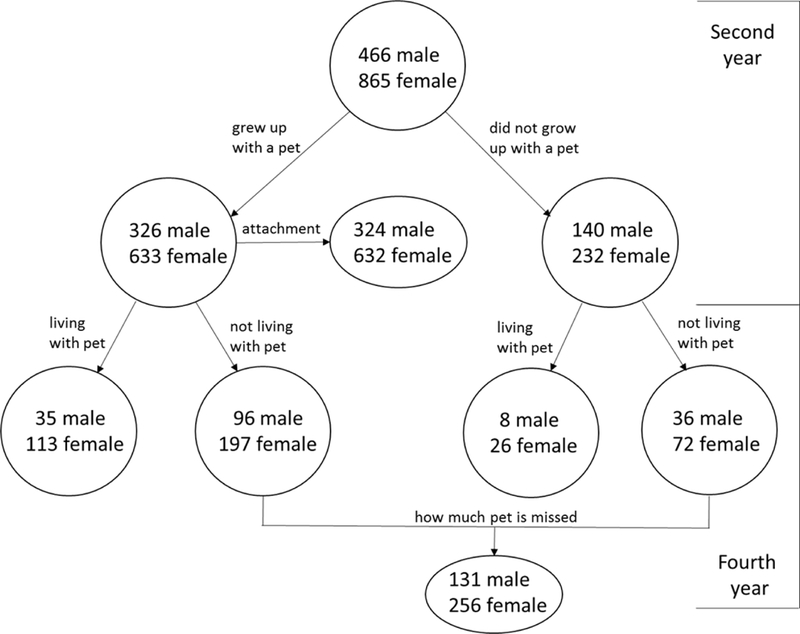

A total of 1331 participants (466 males and 865 females) completed the pet ownership items on the S4S second year survey. Table 1 shows the sample demographics by gender. In the fourth year survey, 175 males and 408 females in the cohort responded to the question of whether or not they were currently living with their pet. Figure 1 provides a graphical presentation of the flow of the student sample surveyed in this cohort according to their responding to the second and fourth year pet related questions.

Table 1.

Student Sample Demographics by Gender

| Male | Female | Total Responding |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) |

| Year 1 Age | 358 | 18.50 (0.35) | 683 | 18.45 (0.36) | 1041 | 18.47 (0.36) |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 102 | 21.94 | 134 | 15.69 | 236 | 17.89 |

| Black/AA | 71 | 15.27 | 215 | 25.18 | 286 | 21.68 |

| Other | 46 | 9.89 | 128 | 14.99 | 174 | 13.19 |

| White | 246 | 52.90 | 377 | 44.15 | 623 | 47.23 |

| Grew Up with Pet | ||||||

| Yes | 326 | 69.96 | 633 | 73.18 | 959 | 72.05 |

| No | 140 | 30.04 | 232 | 26.82 | 372 | 27.95 |

Note. AA=African-American

Figure 1.

Flow of College Student Cohort Responding to Pet Questions in the Second and Fourth Year of College

Most of the 1331 participants grew up with at least one pet (72%, n=959). Most childhood pets were dogs (54%, n=732), followed by a pet other than cat or dog (39%, n=527), and cats (33%, n=440). Many participants (58%, n=558) grew up with more than one type of pet. All but 3 participants who grew up with pets responded to the attachment question with most indicating strong attachment to their childhood pet (M=75.2, SD=22.6). Following an analysis of variance showing no significant differences on internalizing symptoms in the first year by pet species (F=0.14, df=2,394, p=0.86), species were combined into a single childhood pet ownership category.

Personality was assessed by the Big Five Personality Inventory in the first year. Significant personality differences were found between participants growing up with and without pets on openness (t=4.99, df=1319, p<0.001) and neuroticism (t=2.39, df=1320, p=0.016). Participants who grew up with a pet had higher average scores on both openness and neuroticism. No significant differences between groups were found for conscientiousness (t=0.66, df=1320, ns), agreeableness (t=1.00, df=1320, ns), or extraversion (t=0.93, df=1320, ns).

Growing up with a pet, internalizing symptoms, and social support across 4 years of college

Table 2 shows comparisons in internalizing symptoms and social support across the four years for participants who grew up with and without pets. As evident in Table 2, response rates for these items varied from year to year for the 1331 participants completing the pet ownership items in the second year. Most students in our sample completed the first year Spring survey (90%), second year spring survey (97%) and third year spring survey (62%) with over half still completing the fourth year spring survey (53%). In the fall of the first year, there were no significant differences between those growing up with or without pets in mean level of internalizing symptoms. Internalizing symptoms differed significantly starting in the spring of the first year (t=2.73, df=1198, p=0.006) and continuing through the second (t=5.07, df=765, p<0.001), third (t=2.21, df=819, p=0.027) and fourth (t=2.93, df=701, p=0.003) years, with participants growing up with a pet scoring consistently higher on internalizing symptoms. Although significant, effect sizes for the differences are generally small, ranging from 0.17 to 0.29. Figure 2 shows the trend in internalizing symptoms across the four years.

Table 2.

Student Cohort Internalizing Symptoms and Social Support across All Four Years of College by Growing Up with a Pet

| Did not grow up with pet |

Grew up with pet | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | T(df) | P | d | |

| Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||

| First year, fall | 288 | 14.34 (5.88) | 753 | 14.87 (5.99) | 1.27 (1039) | 0.205 | 0.09 |

| First year, spring | 331 | 15.66 (6.32) | 869 | 16.76 (6.22) | 2.73 (1198) | 0.006 | 0.18 |

| Second year, spring | 359 | 14.34 (5.56) | 934 | 16.19 (6.61) | 5.07 (7.65) | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| Third year, spring | 240 | 14.89 (6.35) | 581 | 15.93 (6.06) | 2.21 (819) | 0.027 | 0.17 |

| Fourth year, spring | 213 | 14.78 (6.17) | 490 | 16.39 (6.90) | 2.93 (701) | 0.003 | 0.24 |

| Social Support | |||||||

| First year, fall | 279 | 6.58 (2.35) | 745 | 6.80 (2.16) | 1.40 (1022) | 0.163 | 0.10 |

| First year, spring | 319 | 5.61 (2.33) | 845 | 5.96 (2.27) | 2.30 (1162) | 0.021 | 0.15 |

| Second year, spring | 349 | 5.95 (2.22) | 929 | 6.24 (2.24) | 2.05 (1276) | 0.040 | 0.13 |

| Third year, spring | 230 | 5.77 (2.36) | 578 | 6.39 (2.19) | 3.60 (806) | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Fourth year, spring | 206 | 6.05 (2.48) | 479 | 6.30 (2.28) | 1.30 (683) | 0.194 | .011 |

Note: Fall and spring refer to semesters during which student surveys were completed.

Higher scores reflect greater internalizing symptoms and greater social support.

Figure 2.

Growing Up with and without a Pet and Mean Level of Internalizing Symptoms with Confidence Intervals Across Four Years of College

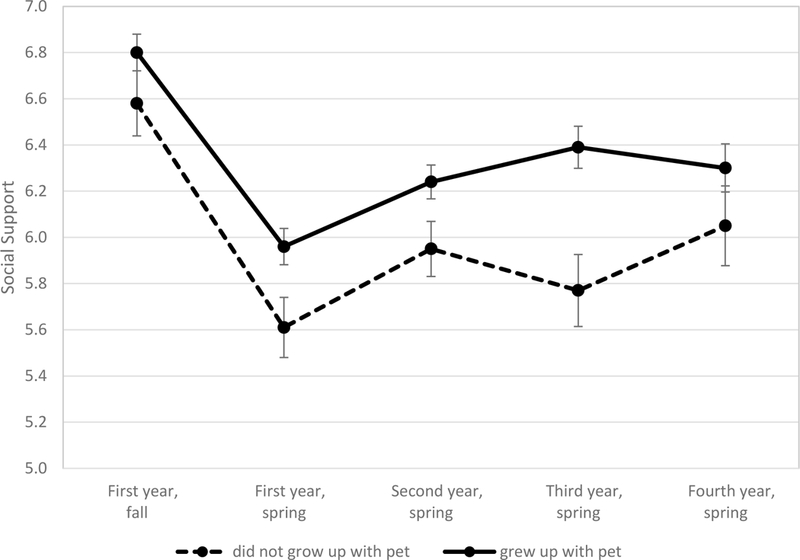

As with internalizing symptoms, social support did not significantly differ in the fall first survey between those participants who grew up with and without pets. Social support differed significantly in the spring of first year (t=2.30, df=1162, p=0.021) through the second (t=2.05, df=1276, p=0.040) and third (t=3.60, df=806, p<0.001) year. Effect sizes were generally small, ranging from 0.15 to 0.28. As shown in Figure 3, those who grew up with a pet scored higher on social support from spring of first year through spring of third year, but not in the spring of fourth year.

Figure 3.

Growing Up with and without a Pet and Mean Level of Social Support with Confidence Intervals across Four Years of College

Currently living with a pet and internalizing symptoms

Of the 1331 participants in the cohort, 43% (n=583) indicated they owned a pet in their fourth year with 31% (n=182) responding they were living with their pet and 69% (n=401) responding they were not living with their pet. Significant gender differences were found with a larger proportion of females living with their pet than males (34% vs 24.6%; χ2=5.14, df=1, p=0.023). Further, females living with their pet reported a higher mean level of internalizing symptoms than those who were not (t=2.81, df=239.86, p<0.001), although no differences were noted for males living with and without their pets (t=1.12, df=170, ns).

For the 401 participants not currently living with their pet, no significant difference was detected in the proportion of males or females who missed their pet a great deal (scoring at or above the 75th percentile; 21.1% male, 29.7% female, χ2=2.73, df=1, ns). Although no significant differences were found in mean level of internalizing symptoms between male participants who miss their pet a great deal; and those who do not (t=0.00, df=105, ns), significant differences were found in females (t=2.79, df=216, p=0.005). On average, females who miss their pet a great deal have higher levels of internalizing symptoms than females who do not.

Pet ownership variables as predictors of internalizing symptoms

A regression model was used to examine simultaneously the effects of three possible pet ownership predictor variables (currently living with a pet, having grown up with a pet, and the interaction between the two) in addition to possible covariates of gender, social support, and personality, on internalizing symptoms in the fourth year. In the initial fit of this model, the interaction between living with a pet and growing up with a pet was not significant and subsequently dropped from the model. In addition, personality dimensions that were non-significant were excluded from the final model. The final model is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fitted Regression Model for the Relationship between Internalizing Symptoms in the Fourth Year of College and Growing Up with a Pet, Currently Living with a Pet, Social Support, Gender, and Personality

| Parameter | β | SE | p | Partial R2 | F-statistic* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.17 | 2.84 | <0.0001 | - | |

| Social Support | −0.68 | 0.11 | <0.0001 | 0.0732 | 38.73 |

| Gender (Male) | −1.53 | 0.60 | 0.0105 | 0.0416 | 6.59 |

| Living with a pet (no) | −1.14 | 0.55 | 0.0392 | 0.0103 | 4.27 |

| Grew up with a pet (no) | −1.03 | 0.60 | 0.0843 | 0.0086 | 2.99 |

| Neuroticism | 0.73 | 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.0131 | 61.26 |

| Openness | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.0003 | 0.0796 | 13.22 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.38 | 0.15 | 0.0102 | 0.0179 | 6.65 |

| Model R2 | 0.2444 | ||||

| Model RMSE | 5.9915 | ||||

df = 1557

Regression results revealed that living with a pet was a significant predictor of internalizing symptoms in the fourth year (F=4.27, df=1, 1557, p=0.039). Gender (F=6.59, df=1, 1557, p=0.010), social support (F=38.73, df=1, 1557, p<0.001), neuroticism (F=61.26, df=1,1557, p<0.001), openness (F=61.26, df=1, 1557, p<0.001) and conscientiousness (F=6.65, df=1, 1557, p=0.010) also contributed significantly to the model. The model variables accounted for 24.4% of the internalizing symptom variance with modest contributions by each variable. Participants living with a pet in their fourth year had higher levels of internalizing symptoms on average than those who did not (16.48 versus 15.32 respectively) and females had higher average levels of internalizing symptoms than males (16.59 versus 15.21). In addition, higher social support and conscientiousness were associated with lower internalizing symptoms on average, while higher levels of neuroticism and openness were associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms (see Table 3).

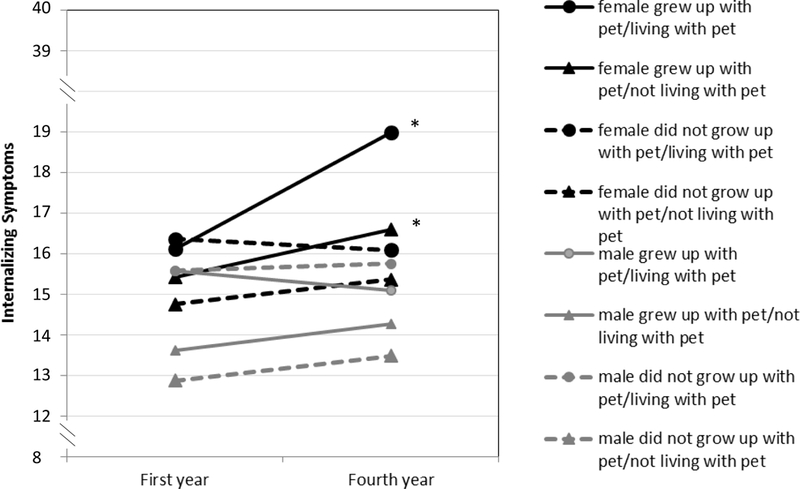

Figure 4 plots the model estimated least square means of internalizing symptoms in the first and fourth year by growing up with a pet, living with a pet and gender. The increased internalizing symptoms for females growing up with pets is apparent, with paired difference results (adjusted for significant covariates) showing significant differences between Years 1 and 4 for females who grew up with pets and are currently living with (t=5.54, df=553, p<0.005) or without pets (t=3.52, df=553, p<0.005). No differences in internalizing symptoms between Years 1 and 4 were found for females not growing up with pets and for males growing up with or without pets, regardless of whether or not they lived with pets in Year 4.

Figure 4.

Mean Level of Internalizing Symptoms (IS) in the First and Fourth Year of College by Childhood Pet Ownership and Gender (IS scale range = 8 – 40) , *p-values < 0.005

Intrigued by these results, we took a closer look at levels of internalizing symptoms by gender in the first year and living with a pet in the fourth year. We were interested in whether higher levels of internalizing symptoms in the first year were related to living with a pet in the fourth year and if any relationship found was moderated by gender. Two levels of internalizing symptoms were compared. A higher level of internalizing symptoms was defined by achieving the 75th percentile of the sum of anxiety and depression scores in the fall first year.

About 23% (n=37) of males and 30.4% (n=112) of females with lower levels of internalizing symptoms lived with their pet in their fourth year and 26% (n=14) of males and 46.2% (n=55) of females with higher internalizing symptoms lived with their pet in their fourth year. There was no significant difference in males with respect to level of internalizing symptoms and whether or not they lived with a pet in their fourth year (χ2=0.19, df=1, ns), however, the proportion of females with higher internalizing symptoms living with a pet in their fourth year was higher (about 16% higher) than for females with a lower level of internalizing symptoms (χ2=8.06, df=1, p=0.001,). Overall, females with higher levels of internalizing symptoms were 1.52 times more likely (95% CI: 1.16, 2.01) to live with a pet in their fourth year. Males with higher levels of internalizing symptoms were just as likely to live with a pet in their fourth year as they were to not live with a pet (RR=1.13, 95% CI: 0.65, 1.97).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to advance human-animal interaction research with a longitudinal investigation of the relationship between pet ownership, social support, and mental health outcomes in a cohort of students as they enter college their first year and through their 4-year college experience. Results reveal interesting gender differences in the relationship between pet ownership variables and internalizing symptoms in this student cohort.

Students who grew up with a pet maintained higher social support (except for their fourth year), but also greater internalizing symptoms throughout the remainder of their college years. The pattern of increased internalizing symptoms for students with childhood pets contrasts with a prior study showing less personal distress in students growing up with pets compared with those who did not (Daly & Morton, 2009). Personal distress in that study was measured as a dimension of empathy, assessed by the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, and measurement differences may explain the differences in results.

There is some precedence for finding increased internalizing symptoms associated with pet ownership, albeit with current pet ownership in adults. Two studies reported increased depression in some adult pet owners (Miltiades & Shearer, 2011; Tower, 2006), but a dearth of research exists in this area, particularly for pet ownership and college students. These results suggest that any benefit to social support that may be provided by growing up with pets does not extend to lessening internalizing symptoms once students enter college.

Pronounced gender differences were found in internalizing symptoms for students living with a pet in the fourth year. By the time students were completing their fourth year, more females were living with their pets than males and these females had higher levels of internalizing symptoms than females who did not live with their pets. And although similar proportions of males and females not living with their pets missed them a great deal, females who missed their pets a great deal had higher levels of internalizing symptoms than females who missed their pets less, whereas no such differences were found for males. These results suggest a possible unique relationship between internalizing symptoms in females and their relationship with their pets not seen in male students. Again however, any social support provided by living with a pet does not appear to mitigate internalizing symptoms.

The importance of gender was further confirmed in the regression model predicting internalizing symptoms in the fourth year. Only one of the three predictor variables, currently living with a pet, was found to predict internalizing symptoms in the fourth year, with gender, social support, and three personality dimensions making significant contributions to the model as well. Living with a pet, being female, having lower social support, increased neuroticism and openness, and decreased conscientiousness contributed to increased internalizing symptoms in the fourth year. The model variables accounted for 24% of the internalizing symptom variance in this model and the contribution of significant variables was modest. Other known variables contributing to internalizing symptoms, such as substance abuse, and socioeconomic status, were not addressed in this study and are important to consider in future studies.

It is unclear what causal factors drive the results, highlighting the need for further research. Although females currently living with a pet had greater internalizing symptoms, the relationship is associational and not causal. Females with higher internalizing symptoms in their first year were 1.5 times more likely to live with a pet in their fourth year. Perhaps females experiencing higher levels of internalizing symptoms choose to live with pets for comfort and/or companionship. An alternative explanation may be that the responsibility of owning a pet may disproportionately increase stress in female students and thereby contribute to internalizing symptoms. Also, females living with pets may substitute pets for human companionship, negatively impacting available social support and contributing to increased internalizing symptoms. Future studies assessing motivation for living with a pet may shed more insight into this relationship.

Females not living with their pets and who miss their pets a great deal also had higher internalizing symptoms than females who miss their pets less. Greatly missing a pet after entering college may contribute to the increased internalizing symptoms seen from the first year through the fourth spring semesters. We were not able to assess missing a pet (or living with a pet) other than in the fourth year but further study of the contribution of missing a pet to internalizing symptoms is warranted. If further research supports the relationship between pet ownership variables and internalizing symptoms, particularly for female college students, asking incoming students about current and past pet ownership could prompt early screening for internalizing symptoms.

Recent research documents the emotional closeness between college students and their pets with no significant differences found in closeness between students and their pets and students and their closest family members (S. B. Barker, Barker, McCain, et al., 2017). With many students unable to live with their pets during the college years, the effect of separation from a close pet warrants further research. One early study of college student homesickness noted that students included missing pets in defining homesickness (Fisher & Hood, 1987).

Practical application of these results support the relatively recent trend in bringing dogs on campus to reduce student stress. Animal-assisted interventions (AAI) have been found to be very popular with students (S. B. Barker, Barker, & Schubert, 2017) and shown to reduce college student stress (S. B. Barker, Barker, McCain, & Schubert, 2016) and homesickness (Binfet & Passmore, 2016) and increase life satisfaction (Binfet, 2017). Further development and evaluation of AAI programs on campus are needed to further our understanding of the potential of AAI to moderate the impact of stressful college experiences on mental health outcomes.

One aim of this study was to build on prior research to investigate the relationship between pet ownership, social support, and internalizing symptoms in college students. This aim was accomplished in using a longitudinal design, large sample size, strong minority participation, and several known covariates. Although students self-selected to participate in the survey, a high level of participation was achieved with 68% of incoming freshmen participating in the fall semester and 88% completing the follow-up survey in the spring. Although many pet ownership studies are limited by predominantly white participants, approximately half of our survey respondents were non-white students. The sample, although generally representative of the larger student body at this university, may not be representative of other higher education institutions.

Study limitations and directions for future research

This survey relied on self-report and students responded to the pet ownership and attachment questions retrospectively. Although students’ recall of whether they grew up with a pet is less likely to be affected by time, their level of attachment to their pet may be influenced by time and separation from the pet. The S4S survey length prevented us from asking more detailed questions about pet ownership: when and for how long students lived with childhood pets, how many students left pets to enter college, and how many lived with pets in each year of college. Further studies are needed to assess detailed pet ownership data, past and present, along with regular assessment of missing one’s pet, in part to address heterogeneity in pet ownership that may dilute ownership effects, but to further explore the relationship between pet ownership characteristics and mental health outcomes.

It is important to note that causation cannot be established based on study results. Although pet ownership in females is associated with increased internalizing symptoms, it is not known whether females choose to live with pets in their fourth year of college because of these symptoms. Assessing student motivation for living with pets in future studies will inform our understanding of this association.

Another limitation is the binary variable used in the survey to assess gender. All students may not have been represented in the male-female dichotomous variable. However, less than 1% (n=12) of participants failed to respond to the gender item. Female participation (65%) in the study was overrepresented compared with the overall student body (57%) although racial/ethnic diversity was identical.

Internal consistency in our sample was low on several BFI scales. Cronbach alpha levels on Openness and Agreeableness were below 0.70 which is generally considered poor reliability. Therefore results from these two scales should be interpreted with caution.

There are pros and cons of contributing items to a larger survey. Imbedding the few pet-related items in the larger S4S survey minimized item order bias and the transparency of our research aim. The pet-related items did not appear until later in the survey after many substance use, behavioral, and personality questions. Although we gained access to a much larger and representative sample, we were limited to adding a few items because of S4S survey length and concerns regarding measurement burden. We were also confined to the existing S4S survey items. For example, personality was only assessed in the Year 1 survey and lack of personality results in Year 4 prevented us from addressing the possible effect of changes in continuity on living with a pet in Year 4. We were also unable to assess the socioeconomic status (SES) of students or their parents. Students growing up with pets or currently living with pets may be from families of higher SES. Including SES in future studies is important to address this potential confound. However, the longitudinal study offered a rich opportunity for a preliminary query of pet ownership and mental health outcomes in a large student cohort across the 4-year college experience. The complex data collection method afforded by the longitudinal design is uncommon in the human-animal interaction literature and addresses the call to go beyond short-term impact to assess outcomes over time.

Conclusion

Although the majority of U.S. households include pets, we know little about the effect of growing up with a pet on mental health outcomes in young adults as they enter and complete college or why some students choose to live with pets during college and the effect of that decision on mental health outcomes. This study contributes to that discussion, showing distinct gender differences in the relationship between pet ownership and internalizing symptoms. Although a positive relationship was found for internalizing symptoms and female students who either live with their pets or who miss their pets a great deal, more study is needed to advance our knowledge of this relationship and to determine whether some aspect of pet ownership contributes to female vulnerability to internalizing symptoms or if females experiencing higher levels of internalizing symptoms choose to live with pets for comfort or companionship.

Acknowledgements

Spit for Science: The VCU Student Survey has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA017828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. We would like to thank the VCU students for making this study a success, as well as the many VCU faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project. This study was also supported by the VCU School of Medicine Center for Human-Animal Interaction.

Appendix

Pet Ownership Items

First College Year Survey Items

-

1.

Did you grow up with a dog?

( ) yes

( ) no

( ) I choose not to answer

-

2.

Did you grow up with a cat?

( ) yes

( ) no

( ) I choose not to answer

-

3.

Did you grow up with another pet?

( ) yes

( ) no

( ) I choose not to answer

[If the answers to 1, 2, and 3 are all “no” skip to next section.]

-

4.How attached were you to your favorite pet(s)?*

*Note: Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

*Note: Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

Fourth College Year Survey Items

1. If you own a pet, is it currently living with you? Yes___ No___

- 1a. If no, how much do you miss your pet?*

*Note: Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

*Note: Online this item is displayed as a sliding bar. As students move the sliding bar, the locations on the scale are associated with a value from 0 to 100.

Contributor Information

Sandra B. Barker, Email: Sandra.barker@vcuhealth.org, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Human-Animal Interaction, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

Christine M. Schubert, Email: christine.schubertkabban@afit.edu, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, USA.

Randolph T. Barker, Email: rbarker@vcu.edu, School of Business, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

Sally I-Chun Kuo, Email: ickuo@vcu.edu, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Kenneth S. Kendler, Email: Kenneth.kendler@vcuhealth.org, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Danielle M. Dick, Email: ddick@vcu.edu, Departments of Psychology, African American Studies, and Human and Molecular Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University.

References

- American College Health Association (2017). American College Health Association-national college health assessment II: Spring 2017 reference group data report. Retrieved: http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II_SPRING_2017_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf

- American College Health Associaiton. (2015). National college health assessment: Spring 2015 reference group executive summary. Retrieved from http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2015_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Interactive guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–8, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT.

- Ahearn E 1997. The use of visual analog scales in mood disorders: A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 31, 569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RC 1969. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 62, 989–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KM, Blascovich J, Tomaka J, & Kelsey RM (1991). Presence of human friends and pet dogs as moderators of autonomic responses to stress in women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 582–589. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, & Barker RT (1988). The human-canine bond: Closer than family ties. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 10, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Barker RT, McCain NL, & Schubert CM (2016). A randomized crossover exploratory study of the effect of visiting therapy dogs on college student stress before final exams. Anthrozoös, 29, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Barker RT, McCain NL, & Schubert CM (2017). The effect of a canine-assisted activity on college student perceptions of family supports and current stressors. Anthrozoös, 30, 595–606. [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Barker RT & Schubert CM (2017).Therapy dogs on campus: A counseling outreach activity for students preparing for final exams. The Journal of College Counseling, 20, 278–288. [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Knisely JS, McCain NL & Best AM (2005). Measuring stress and imune response in healthcare professionals following interaction with at therapy dog: A pilot study. Psychological Reports, 96, 713–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Knisely JS, McCain NL, Schubert CM, & Pandurangi AK (2010). Exploratory study of stress-buffering response patterns from interaction with a therapy dog. Anthrozoös, 23, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, Pandurangi AK and Best AM (2003). Effects of animal-assisted therapy on patients’ anxiety, fear, and depression before ECT. Journal of ECT, 19, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker SB, & Wolen AR (2008). The benefits of human–companion animal interaction: A review. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 35(4), 487–495. doi: 10.3138/jvme.35.4.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck L, & Madresh EA (2008). Romantic partners and four-legged friends: An extension of attachment theory to relationships with pets. Anthrozoös, 21(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beetz AM (2017). Theories and possible processes of action in animal assisted interventions. Applied Developmental Science, 21(2), 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, & Sammut S (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, & Nestadt G (2004). Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five‐factor model of personality: A higher‐and lower‐order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety, 20(2), 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binfet JT (2017). The effects of group-administered canine therapy on university students’ wellbeing: A randomized controlled trial. Anthrozoös, 30, 397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Binfet JT, & Passmore HA (2016). Hounds and homesickness: The effects of an animal-assisted therapeutic intervention for first-year university students. Anthrozoös, 29, 441–454. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2016.1181364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S-M, & Olfson M (2008). Mental health of college students and their non–college-attending peers: results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonas S, McNicholas J, & Collis GM (2000). Pets in the network of family relationships: An empirical study. Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets, 209–236. [Google Scholar]

- Brady EU, & Kendall PC (1992). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 244–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandy JM, Penckofer S, Solari-Twadell PA, & Velsor-Friedrich B (2015). Factors predictive of depression in first-year college students. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing Mental Health Services, 53(2), 38–44. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20150126-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain AO (1985). Pets as family members. Marriage & Family Review, 8, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Roberts BW (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12(2), 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cline KMC (2010). Psychological effects of dog ownership: Role strain, role enhancement, and depression. Journal of Social Psychology, 150(2), 117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly B, & Morton LL (2006). An investigation of human-animal interactions and empathy as related to pet preference, ownership, attachment and attitudes in children. Anthrozoös, 19(2), 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Daly B, & Morton LL (2009). Empathic differences in adults as a function of childhood and adult pet ownership and pet type. Anthrozoös, 22(4), 371–382. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Begley S, & Amari F (2012). The emotional life of your brain: Brilliance Audio. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Cleary PA (1977). Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90: A study in construct validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(4), 981–989. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, & Covi L (1977). SCL-90 Administration, scoring and procedures manual-I for the R (revised) version and other instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scales Series. Chicago: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Rickels K, & Rock A (1976). The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, . . . Kendler KS (2014). Spit for science: launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics, 5, 47. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E, & Hefner JL (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NJ, Forney D, Guido F, Renn K, & Patton L (2010). Student development in college: Theory, research and practice (2nd Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rankin MA, Wright EC, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Pava J, & Rosenbaum JF (2000). Anxiety disorders in major depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 41(2), 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S and Hood B (1987). The stress of the transition to university: A longitudinal study of psychological disturbance, absent-mindedness and vulnerability to homesickness. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 425–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann E, Thomas SA, & Son H (2011). Pets, depression and long-term survival in community living patients following myocardial infarction. Anthrozoös, 24(3), 273–285. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadomski AM, Scribani MB, Krupa N, Jenkins P, Nagykaldi Z, & Olson AL (2015). Pet dogs and children’s health: Opportunities for chronic disease prevention? Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, E205. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi A, & Pozzulo JD (2015). Childhood experiences with family pets and internalizing symptoms in early adulthood. Anthrozoös, 28(3), 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, & Bonnenburg AV (1998). An integrative approach to personality research in anthro-zoology: Ratings of six species of pets and their owners. Anthrozoös, 11(3), 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, & Swann WB (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in personality, 37(6), 504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Sandy CJ, & Potter J (2010). Personalities of self-identified “dog people” and “cat people”. Anthrozoös, 23(3), 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Grace TW (1997). Health problems of college students. Journal of American College Health, 45, 243–251. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1997.9936894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grav S, Hellzèn O, Romild U, & Stordal E (2012). Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(1–2), 111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, & Mazel R (1995). User’s manual for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) core measures of health-related quality of life. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog HA (2007). Gender differences in human-animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös, 20(1), 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB, & Finney M (2002). Negative life events and psychological distress among young adults. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 186–201. doi: 10.2307/3090100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2, 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, & Watson D (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 768–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Parello CA (2012). Pet ownership and older women: The relationships among loneliness, pet attachment support, human social support, and depressed mood. Geriatric Nursing, 33(3), 194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M (2001). Issues in the study of personality development. Psychological Inquiry, 12(2), 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- McCune S, Kruger KA, Griffin JA, Esposito L, Freund LS, Hurley KJ, & Bures R (2014). Evolution of research into the mutual benefits of human-animal interaction. Animal Frontiers, 4(3), 49–58. doi: 10.2527/af.2014-0022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melson GF, Peet S, & Sparks C (1991). Children’s attachment to their pets: Links to socio-emotional development. Children’s Environments Quarterly, 8(2), 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Miltiades H, & Shearer J (2011). Attachment to pet dogs and depression in rural older adults. Anthrozoös, 24(2), 147–154. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MK, & Callina KS (2014). Human–animal interaction as a context for thriving and coping in military-connected touth: The Role of Pets During Deployment. Applied Developmental Science, 18(4), 214–223. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2014.955612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nottelmann ED, & Jensen PS (1995). Comorbidity of disorders in children and adolescents. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, 17, 109–155. [Google Scholar]

- Podberscek AL, & Gosling SD (2000). Personality research on pets and their owners: Conceptual issues and review In Podberscek AL, Paul ES, & Serpell JA (Eds.), Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets (pp. 143–167). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Purewal R, Christley R, Kordas K, Joinson C, Meints K, Gee N, & Westgarth C (2017). Companion animals and child/adolescent development: a systematic review of the evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(3), 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, & Trzesniewski KH (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ross SE, Niebling BC, & Heckert TM (1999). Sources of stress among college students. Social Psychology, 61(5), 841–846. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2015). Reports and detailed tables from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/samhsa-data-outcomes-quality/major-data-collections/reports-detailed-tables-2015-NSDUH

- Sherbourne CD, & Stewart AL (1991). MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32, 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Conwell Y, Bowen C, & Van Orden KA (2014). Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging & Mental Health, 18(3), 394–399. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.837147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, & Randall P (2004). Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower RB & Nokota M (2006). Pet companionship and depression: Results from a United States Internet Samples. Anthrozoös, 19(2), 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtte BA, & Jarvis PA (1995). The role of pets in preadolescent psychosocial development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Vidovic VV, Stetic VV, & Bratko D (1999). Pet ownership, type of pet and socio-emotional development of school children. Anthrozoös, 12(4), 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous JP, & Reichers AE (1996). Estimating the reliability of a single-item measure. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 631–634. [Google Scholar]

- Westgarth C, Heron J, Ness AR, Bundred P, Gaskell RM, Coyne KP, . . . Dawson S (2010). Family pet ownership during childhood: Findings from a UK birth cohort and implications for public health research. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 7(10), 3704–3729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7103704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KT, Bohnert AE, Ambrose A, Davis DY, Jones DM, & Magee MJ (2014). Social, behavioral, and sleep characteristics associated with depression symptoms among undergraduate students at a women’s college: a cross-sectional depression survey, 2014. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn–Waxler C, Klimes–Dougan B, & Slattery MJ (2000). Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: Prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Development and Psychopathology, 12(03), 443–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, & Farley GK (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, Young D, Posternak MA, Friedman M, ... & Attiullah N (2006). Developing brief scales for use in clinical practice: the reliability and validity of single-item self-report measures of depression symptom severity, psychosocial impairment due to depression, and quality of life. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 1536–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]