Abstract

Zingiber montanum (Z. montanum) and Zingiber zerumbet (Z. zerumbet) are important medicinal and ornamental herbs in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae. Chloroplast-derived markers are useful for species identification and phylogenetic studies, but further development is warranted for these two Zingiber species. In this study, we report the complete chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet, which had lengths of 164,464 bp and 163,589 bp, respectively. These genomes had typical quadripartite structures with a large single copy (LSC, 87,856–89,161 bp), a small single copy (SSC, 15,803–15,642 bp), and a pair of inverted repeats (IRa and IRb, 29,393–30,449 bp). We identified 111 unique genes in each chloroplast genome, including 79 protein-coding genes, 28 tRNAs and 4 rRNA genes. We analyzed the molecular structures, gene information, amino acid frequencies, codon usage patterns, RNA editing sites, simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and long repeats from the two chloroplast genomes. A comparison of the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes detected 489 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 172 insertions/deletions (indels). Thirteen highly divergent regions, including ycf1, rps19, rps18-rpl20, accD-psaI, psaC-ndhE, psbA-trnK-UUU, trnfM-CAU-rps14, trnE-UUC-trnT-UGU, ccsA-ndhD, psbC-trnS-UGA, start-psbA, petA-psbJ, and rbcL-accD, were identified and might be useful for future species identification and phylogeny in the genus Zingiber. Positive selection was observed for ATP synthase (atpA and atpB), RNA polymerase (rpoA), small subunit ribosomal protein (rps3) and other protein-coding genes (accD, clpP, ycf1, and ycf2) based on the Ka/Ks ratios. Additionally, chloroplast SNP-based phylogeny analyses found that Zingiber was a monophyletic sister branch to Kaempferia and that chloroplast SNPs could be used to identify Zingiber species. The genome resources in our study provide valuable information for the identification and phylogenetic analysis of the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae.

Introduction

Zingiber Boehm., belonging to the family Zingiberaceae, consists of between 100 and 150 species, all of which are widely distributed in southern and southeastern Asia, with particular concentrations in Thailand and southern China [1–4]. There are more than 40 Zingiber species in China, among which 13 are reported to have medicinal value [1, 2, 5]. In addition, most species have an assemblage of tightly clasped, overlapping bracts that often age to yellow, red, or chestnut brown and are often highly showy and long-lived, leading to the cultivation of a number of species for landscaping and cut-flower uses [2–4]. Both Zingiber montanum (J. König) A. Dietr and Zingiber zerumbet (Linnaeus) Rosc. ex Smith are useful medicinal and ornamental plants in this genus [2–5]. Z. montanum is endemic to the Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and Yunnan provinces of China [4]. Chemical compositions of the Z. montanum rhizome have antidiarrheal, antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, allelopathic and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties [3, 4, 6–8]. Z. zerumbet, commonly known as “shampoo ginger”, is found across southern China (Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and Yunnan provinces), most of Southeast Asia, Myanmar, India, and Sri Lanka [1–4]. Zerumbone from the Z. zerumbet rhizome has been reported to suppress the phagocytic activity of human neutrophils [9], to prevent and treat tooth decay disease [10], to cure osteoarthritis of the knee [11], and to treat various immune-inflammatory related disorders [12].

Zingiber species have been known taxonomically, with many species based on both vegetative and floral characteristics [1–5]. However, a number of defining morphological features are often inconsistent and variable [1–4, 13]. Visually, Zingiber species are relatively similar to one another’s vegetative parts in nonflowering seasons [1–4], making it highly difficult to morphologically distinguish among species in the nonflowering stage. Recently, several studies have also used molecular data to identify some Zingiber species [13, 14]. The results showed a weak resolution among six Zingiber species (Zingiber corallinum, Zingiber wrayi, Zingiber sulphureum, Zingiber gramineum, Zingiber ellipticum and Zingiber species) using nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and chloroplast matK regions [13]. Through amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)-based DNA markers, the results have indicated that Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet are phylogenetically closer to each other than to Zingiber officinale [14]. These analyses have succeeded in clarifying the phylogenetic relationships and degrees of variation among Zingiber species, but in general have been limited in breadth of resolution. Therefore, a more accurate method of plant identification is essential for Zingiber species. The complete chloroplast genome contains more effective DNA markers, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertion/deletions (indels) and hotspot variable regions, which can be used for accurate species identification. In recent years, more than 25 complete chloroplast genomes have been sequenced in the family Zingiberaceae [15–26]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet have not yet been elucidated. To date, only two Zingiber species’ whole chloroplast genomes have been reported, namely, Zingiber spectabile (GenBank JX088661) and Z. officinale (NC_044775) [18], hindering the molecular plant identification of Zingiber species.

Chloroplasts are photosynthetic organelles that can transform light energy into chemical energy in green plants [27–29]. These organelles have their own chloroplast genomes that encode 110–130 genes with a size range of 120–180 kb and have a typical quadripartite structure consisting of a large single copy (LSC) region, a small single copy (SSC) region, and two copies of inverted repeats (IRs) [18–26]. Whole chloroplast genomes have been widely exploited to resolve plant phylogenies, origin problems and species identification [15–17, 22–26, 30].

In this study, we first sequenced and assembled the complete chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet using combinations of Illumina and PacBio sequencing platforms, respectively. Second, we explored the molecular features of each genome and compared them with eight other members of the family Zingiberaceae. Third, we analyzed the codon usage, RNA editing, SNPs and indels in the chloroplast genome sequences of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet. Fourth, we detected simple sequence repeats (SSRs), long repeats, highly divergent hotspot regions and phylogenetic relationships of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet and compared them with two reported Zingiber species (Z. officinale and Z. spectabile). Our findings are expected to be useful for species identification and phylogenetic studies in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

No specific permits were required for the collection of specimens for this study. This research was carried out in compliance with the relevant laws of China.

Plant material, chloroplast DNA extraction and sequencing

Fresh leaves were collected from Z. zerumbet and Z. montanum plants from the resource garden of the environmental horticulture research institute (23° 23' N, 113° 26' E), Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou, China. Total chloroplast DNA was extracted from these leaves using the improved sucrose gradient centrifugation method [31]. The quality and quantity of extracted chloroplast DNA were estimated using an ND-2000 spectrometer (Wilmington, DE, USA) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. Chloroplast DNA samples of good integrity with both optical density (OD) 260/280 and OD 260/230 ratios greater than 1.8 were used for sequencing.

Two libraries with insert sizes of 300 bp and 10 kb were constructed after DNA purification for each sample. Then, the samples were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten instrument (Biozeron, Shanghai, China) and a PacBio Sequel platform (Biozeron, Shanghai, China), respectively. The qualities of Illumina raw reads and PacBio raw reads were determined using FastQC. After filtering the raw data, 43.4 M and 73.9 M clean data from 150 bp Illumina paired-end reads were generated for Z. zerumbet and Z. montanum, respectively, and 0.85 M and 0.98 M clean data from 8–10 kb subreads were generated from the two species, respectively.

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotations

First, the clean Illumina reads were assembled using SOAPdenova (version 2.04) with default parameters into principal contigs [32], and all contigs were sorted and joined into a single draft sequence using the Geneious version 11.0.4 software [33]. Next, the BLASR software was used to compare the PacBio clean data with the single draft sequence and to extract the correction and error correction [34]. Next, the corrected PacBio clean data were assembled using Celera Assembler (version 8.0) with default parameters, generating scaffolds [35]. Next, the assembled scaffolds were mapped back to the Illumina clean reads using GapCloser (version 1.12) for gap closing [32]. Finally, the redundant fragment sequences were removed, thereby generating the final assembled chloroplast genomic sequence.

Annotations of the chloroplast genomes were conducted using the online tool DOGMA (Dual Organellar Genome Annotator) [36] with default parameters and checked manually. BLASTn searches of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website were used to identify and confirm both tRNA and rRNA genes. Last, further verification of the tRNA genes was carried out using tRNAscanSE with default settings [37]. Circular maps of the chloroplast genomes were drawn using OGDRAWv1.3.1 with default parameters and subsequent manual editing [38].

Codon usage and RNA editing site prediction

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in protein-coding genes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet was calculated using the MEGA7 software [39]. Amino acid frequency was also calculated and expressed by the percentage of the codons encoding the same amino acid divided by the total codons. RNA editing sites of 21 protein-coding genes from the two species were investigated using the online program Predictive RNA Editor for Plants (PREP) suite (http://prep.unl.edu/) with a cutoff value of 0.8 [40].

SNPs and indel detection

To develop specific markers for distinguishing Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet, the whole chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet were aligned using the MUMmer software [41] and adjusted manually where necessary using Se-Al 2.0 [42]. The Z. montanum chloroplast genome was used as the reference for the SNP and indel analyses.

SSRs and long repeat analyses of four Zingiber species

SSRs of the four Zingibers chloroplast genomes, including Z. montanum, Z. zerumbet, Z. officinale and Z. spectabile, were identified using MIcroSAtellite (MISA) (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/) [43] with the following settings: 8 for mono-, 5 for di-, 4 for tri-, and 3 for tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotide repeat motifs. The online REPuter software [44] was used to establish the size and location of long repeat sequences, including forward, palindrome, reverse and complement repeat units in the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes. The minimal repeat size was set as 30 bp with a repeat identity of 90% and a Hamming distance of 3.

Sequence divergence analyses of the four Zingiber species

To compare the chloroplast genome of Z. montanum with three other Zingiber species (Z. zerumbet, Z. officinale and Z. spectabile), the mVISTA tool in Shuffle-LAGAN mode [45] was performed using the annotated chloroplast genome of Z. montanum as the reference. To detect the variation in the boundaries between the IR and SC regions of the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes, the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes were compared and analyzed. The nucleotide variability (Pi) among the four whole Zingiber chloroplast genomes was calculated using DnaSP version 5.1 [46] with the following settings: window length of 600 bp and step size of 200 bp.

Selection pressure analysis of the four Zingiber species

To estimate selection pressures, nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates of protein-coding genes between the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and the other three Zingiber species (Z. zerumbet, Z. spectabile and Z. officinale) were calculated. The Ka/Ks values for each protein-coding gene were estimated by the KaKs_Calculator [47] with default parameters.

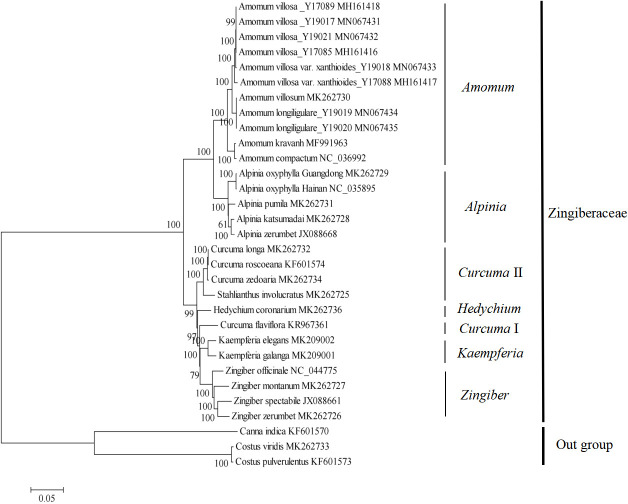

Phylogeny in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae

In this study, a total of 29 whole chloroplast genome sequences were downloaded from the NCBI database to determine the phylogenetic positions of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae. Costus pulverulentus, Costus viridis and Canna indica were used as outgroups of the family Zingiberaceae. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the population SNP matrix of the studied plants, which was obtained using a previously described method [16, 17]. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis based on the nucleotide substitution model of Tamura-Nei was conducted to construct the phylogenetic tree with MEGA7 software [39]. The ML analysis was performed with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Results and discussion

Chloroplast genome features of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet

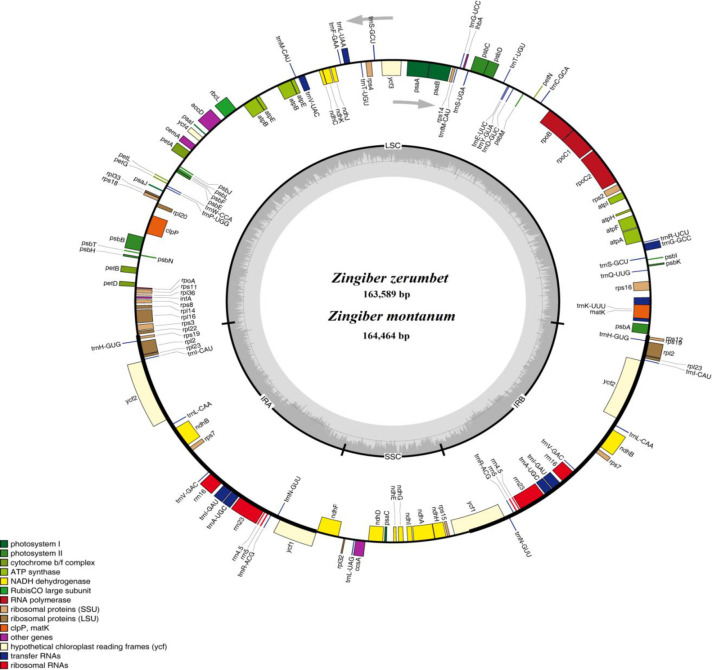

The raw Illumina and PacBio chloroplast sequencing data had been submitted to the NCBI with SRA numbers SRR8185396 and SRR8184511 for Z. montanum, respectively, and SRA numbers SRR8185094 and SRR8184512 for Z. zerumbet, respectively. All of these raw data were in the bioproject PRJNA498576. The two whole chloroplast genome sequences had been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MK262727 and MK262726 for Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet, respectively. The Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes were 164,464 bp and 163,589 bp in length, respectively (Fig 1). Similar to most other angiosperms, the two genomes had typical quadripartite structure circle molecules consisting of a LSC of 87,856 bp in Z. montanum and 89,161 bp in Z. zerumbet, a SSC region of 15,803 bp in Z. montanum and 15,642 bp in Z. zerumbet, and two IR regions of 30,356 bp and 30,449 bp in Z. montanum and each 29,393 bp in Z. zerumbet (Fig 1 and Table 1). The overall GC contents in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet were 35.75% and 36.27%, respectively (Table 1 and S1 Table). Additionally, the GC contents of the two species were the highest (40.46%-41.02%) in the IR regions, the lowest (29.24%-29.64%) in the SSC regions, and moderate (33.63%-34.31%) in the LSC regions (Table 1), which were similar to the chloroplast genomes of other reported species in the family Zingiberaceae [15–26]. Approximately 50.76%-51.37% of the two Zingiber species chloroplast genomes consisted of protein-coding genes (83,496 bp in Z. montanum and 84,042 bp in Z. zerumbet), 1.74%-1.75% of tRNAs (2,876 bp Z. montanum and 2,877 bp in Z. zerumbet), and 5.50%-5.52% of rRNAs (9,046 bp in Z. montanum and 9,046 bp in Z. zerumbet) (S1 Table). For the protein-coding genes, the AT contents of the first, second, and third codons were 55.57%, 62.99%, and 71.26% in Z. montanum, respectively, and 55.35%, 62.61%, and 71.20% in Z. zerumbet, respectively (S1 Table).

Fig 1. Circular gene map of the chloroplast genomes of two Zingiber species.

The gray arrowheads indicate the direction of the genes. Genes shown inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outside the circle are transcribed counterclockwise. Different genes are color coded. The innermost darker gray corresponds to GC content, whereas the lighter gray corresponds to AT content. IR, inverted repeat; LSC, large single copy region; SSC, small single copy region.

Table 1. Characteristics of the chloroplast genomes of ten Zingiberaceae species.

| Genome characteristics | Zingiber montanum | Zingiber zerumbet | Zingiber officinale | Kaempferia galanga | Kaempferia elegans | Curcuma zedoaria | Curcuma longa | Hedychium coronarium | Stahlianthus involucratus | Amomum villosum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank number | MK262727 | MK262726 | NC_044775 | MK209001 | MK209002 | MK262734 | MK262732 | MK262736 | MK262725 | MK262730 |

| Genome size (bp) | 164,464 | 163,589 | 162,621 | 163,811 | 163,555 | 162,135 | 162,176 | 163,949 | 163,300 | 163,608 |

| LSC length (bp) | 87,856 | 89,161 | 87,486 | 88,405 | 88,020 | 86,966 | 86,984 | 88,581 | 87,498 | 88,680 |

| SSC length (bp) | 15,803 | 15,642 | 15,577 | 15,812 | 15,989 | 15,737 | 15,694 | 15,808 | 15,568 | 15,288 |

| IR length (bp) | 30,356/30,449 | 29,393 | 29,779 | 29,797 | 29,773 | 29,716 | 29,749 | 29,780 | 30,117 | 29,820 |

| Total genes (unique) | 141(111) | 141(111) | 133(113) | 133(111) | 133(113) | 141 (111) | 141 (111) | 141(111) | 141(111) | 133(111) |

| CDS (unique) | 87(79) | 87(79) | 87(79) | 87(79) | 87(79) | 87 (79) | 87 (79) | 87(79) | 87(79) | 87(79) |

| tRNA genes (unique) | 46(28) | 46(28) | 38(30) | 38(28) | 38(30) | 46 (28) | 46 (28) | 46(28) | 46(28) | 38(28) |

| rRNA genes(unique) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) |

| GC content (%) | ||||||||||

| Genome | 35.75 | 36.27 | 36.10 | 36.10 | 36.10 | 36.20 | 36.21 | 36.09 | 36.00 | 36.08 |

| CDS | 36.72 | 36.95 | 37.10 | 36.90 | 37.20 | 36.94 | 36.92 | 36.96 | 36.85 | 36.91 |

| LSC | 33.63 | 34.31 | 33.80 | 33.90 | 33.90 | 34.02 | 34.00 | 33.85 | 33.78 | 33.71 |

| SSC | 29.24 | 29.64 | 29.70 | 29.50 | 29.40 | 29.60 | 29.66 | 29.53 | 29.59 | 30.06 |

| IR | 40.51/40.46 | 41.02 | 41.10 | 41.00 | 41.10 | 41.14 | 41.16 | 41.15 | 40.89 | 41.14 |

| Genes with introns | 19 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| CDS in LSC | 61 | 61 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 |

| CDS in SSC | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| CDS in IRa | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| CDS in IRb | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Genes in IRs(unique) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) | 40(20) |

CDS, protein-coding genes; LSC, large single copy region; SSC, small single copy region; IR, inverted repeat.

We detected a total of 141 functional genes consisting of 87 protein-coding genes, 46 tRNAs, and eight rRNAs in the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes, which included 111 unique genes (Tables 1 and 2). Among the 111 unique genes, there were 79 protein-coding genes, 28 tRNAs and four rRNAs in the chloroplast genomes of the two Zingiber species (Table 1). Of the protein-coding genes in the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes, 61 genes were located in the LSC region, 12 genes were in the SSC region and 8 genes were duplicated in the IR regions (Table 1). Eight complete chloroplast genomes, those of Z. officinale, Kaempferia galanga, Kaempferia elegans, Curcuma zedoaria, Curcuma longa, Hedychium coronarium, Stahlianthus involucratus, and Amomum villosum, belonging to six different genera in the family Zingiberaceae were selected for comparisons with Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the Z. zerumbet chloroplast genome had the highest GC content (36.27%), while the Z. montanum chloroplast genome had the lowest GC content (35.75%). Interestingly, the two IR regions in Z. zerumbet (each 29,393 bp) were the shortest, whereas the two IR regions in Z. montanum (30,356 bp and 30,449 bp) were the longest (Table 1). There were no significant variations in the numbers of unique total genes, unique protein-coding genes, unique tRNAs and unique rRNAs observed in comparisons of the two Zingiber chloroplast genomes with those of the other eight selected chloroplast genome sequences (Table 1).

Table 2. Genes present in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet.

| Category | Function | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | Photosystem Ⅰ | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Photosystem Ⅱ | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, lhbA | |

| Cytochrome b/f | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | |

| NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB(×2)*, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Rubisco | rbcL | |

| Self-replication | RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 |

| Large subunit ribosomal proteins | rpl2(×2)*, rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23(×2), rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | |

| Small subunit ribosomal proteins | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7(×2), rps8, rps11, rps12(×2)*, rps14, rps15, rps16*, rps18, rps19(×2) | |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5(×2), rrn5(×2), rrn16(×2), rrn23(×2) | |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC (×4)*, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnfM-CAU, trnG-GCC (×2)*, trnG-UCC, trnH-GUG (×2), trnI-CAU (×2), trnI-GAU (×4)*, trnK-UUU (×2)*, trnL-CAA (×2), trnL-UAA (×2)*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU (×2), trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG (×2), trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU (×2), trnS-UGA, trnT-UGU (×2), trnV-GAC (×2), trnV-UAC (×2)*, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA | |

| Others | Other proteins | accD*, ccsA, cemA, clpP**, infA, matK |

| Proteins of unknown function | ycf1(×2), ycf2(×2), ycf3**, ycf4 |

×2, Gene with two copies; ×4, Gene with four copies

*, Genes containing one intron

**, Genes containing two introns.

A total of 20 genes were duplicated in the IR regions, including eight protein-coding genes (ndhB, rpl2, rpl23, rps7, rps12, rps19, ycf1 and ycf2), eight tRNA genes (trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnL-CAA, trnV-GAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC, trnR-ACG and trnN-GUU), and all four rRNAs (rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16 and rrn23) (Fig 1 and S2 Table). Seventeen genes (trnA-UGC, trnI-GAU, trnG-GCC, trnK-UUU, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, accD, atpF, ndhA, ndhB, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl2, rpl16, rps12 and rps16) contained one intron, while ycf3 and clpP each contained two introns (S3 Table). Among the 19 intron-containing genes, 4 genes (trnA-UAC, trnI-GAU, rpl2 and ndhB) occurred in both IRs, 13 genes (trnG-GCC, trnK-UUU, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, atpF, accD, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl16, rps16, ycf3 and clpP) were distributed in the LSC, one gene (ndhA) was in the SSC, and one gene (rps12) had its first exon in the LSC and the other two exons in both IRs (Fig 1 and S3 Table). In addition, the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes had the longest introns of trnK-UUU (2,683 bp and 2,606 bp, respectively), all of which were included in the coding region of matK (S2 and S3 Tables).

Codon usage and predicted RNA editing site analyses

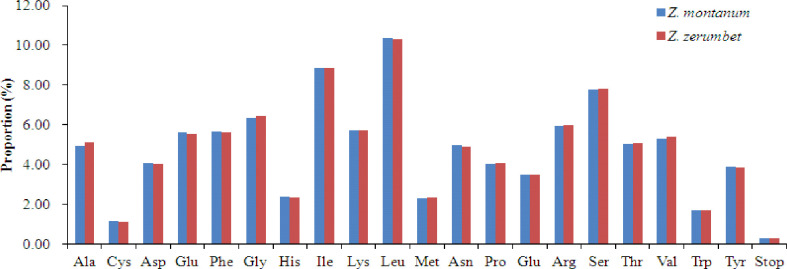

All chloroplast protein-coding genes from Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet were encoded by 27,832 codons and 28,014 codons, respectively. Similar to most reported Zingiberaceae plants [15–18, 20–21], leucine (Leu) was the most prevalent amino acid in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum (2888, 10.37%) and Z. zerumbet (2896, 10.33%). Conversely, cysteine (Cys), which contained 320 codons in Z. montanum (1.14%) and 309 codons in Z. zerumbet (1.10%), was the least frequent amino acid in the chloroplast genomes of these two Zingiber species (Fig 2 and S4 Table). In the chloroplast genes of the two Zingiber species, thirty codons with RSCU>1 were all A/T-ending codons, except for one codon (UUG) that coded for trnL-CAA (S4 Table). Stop codon usage was found to be biased toward TAA (RSCU>1.00). Two amino acids, methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp), showed no codon bias with RSCU values of 1.00 (S4 Table).

Fig 2. Amino acid proportion in Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet protein-coding sequences.

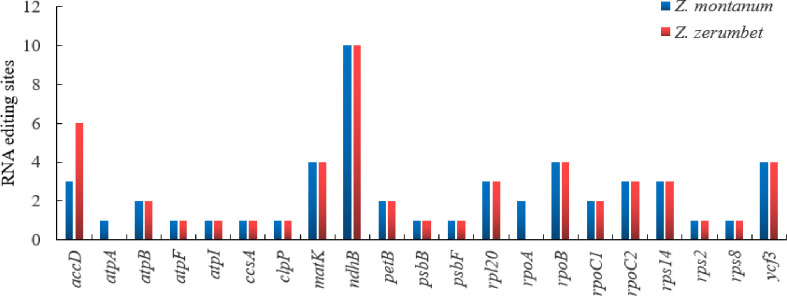

A total of 51 editing sites were identified in 21 protein-coding genes from Z. montanum and 19 protein-coding genes from Z. zerumbet (Fig 3 and S5 Table). In the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes that we sequenced, the ndhB gene had the highest number of potential editing sites (10, 10), followed by accD (3, 6), matK (4, 4), rpoB (4, 4) and ycf3 (4, 4) (Fig 3 and S5 Table). Similar to other reported species, such as two Kaempferia species [16] and three Alpinia species [17], the ndhB gene contained the highest number of editing sites. Of these editing sites, all were C-to-T transitions and occurred at the codon first or second positions (S5 Table). In addition, most RNA editing sites in both species led to hydrophobic amino acids, such as leucine (Leu, L), isoleucine (Ile, I), tryptophan (Trp, W), tyrosine (Tyr, Y), valine (Val, V), methionine (Met, M), and phenylalanine (Phe, F) (S5 Table). Similar RNA editing results have already been revealed by previous reports [16, 17].

Fig 3. Predicted RNA editing sites of protein-coding genes in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet.

SNP and indel detection between Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet

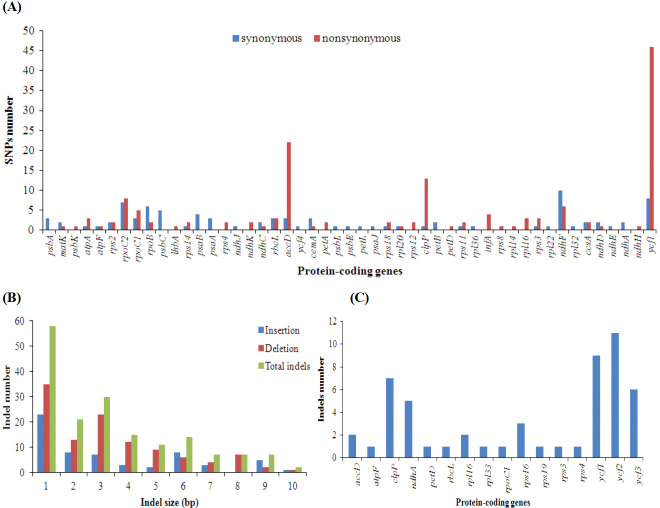

Using the Z. montanum chloroplast genome as the reference, we compared the SNP/indel loci of the chloroplast genome of Z. zerumbet. Two hundred thirty-eight and 251 SNP markers were detected between Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet in protein-coding genes and intergenic regions, respectively (S6 Table). SNP markers were detected in 49 protein-coding genes in the chloroplast genome of Z. zerumbet (Fig 4A and S6 Table). There were 90 synonymous and 148 nonsynonymous SNPs in the protein-coding genes of the Z. zerumbet chloroplast genome (S6 Table). Sixty insertions and 112 deletions were detected between the Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet chloroplast genomes, respectively (Fig 4B and S7 Table). Sixteen protein-coding genes from the Z. zerumbet chloroplast genome contained indels, including accD, atpF, clpP, ndhA, petD, rbcL, rpl16, rpl33, rpoC1, rps16, rps19, rps3, rps4, ycf1, ycf2 and ycf3 (Fig 4C). These results indicated that there were more nucleotide substitutions than between Alpinia species but fewer than observed for Kaempferia species in the family Zingiberaceae. Comparative analyses of chloroplast genomes revealed 304 SNPs between Alpinia pumila and A. katsumadai, 367 SNPs between A. pumila and A. oxyphylla sampled from Guangdong, 331 SNPs between A. pumila and A. zerumbet, 371 SNPs between A. pumila and A. oxyphylla sampled from Hainan [17], and 536 SNPs between K. galanga and K. elegans [16]. By comparison, there were more indels in the two Zingiber species than in two Kaempferia species and three Alpinia species [16, 17]. There were 107 indels between K. galanga and K. elegans [16], 118 indels between A. pumila and A. katsumadai, 122 indels between A. pumila and A. oxyphylla sampled from Guangdong, 115 indels between A. pumila and A. zerumbet, and 120 indels between A. pumila and A. oxyphylla sampled from Hainan [17]. The SNP and indel resources produced in this study could be used for phylogenetic analysis and species identification in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae in the future.

Fig 4. SNP and indel statistics for the Z. zerumbet chloroplast genome.

The Z. montamum chloroplast genome was used as the reference sequence for SNP and indel analyses. (A) Synonymous and nonsynonymous SNPs belonging to different protein-coding genes. The genes with zero SNP were not shown. (B) Insertion, deletion and total indel statistics. (C) Indels belonging to different protein-coding genes.

SSR and long repeat analyses

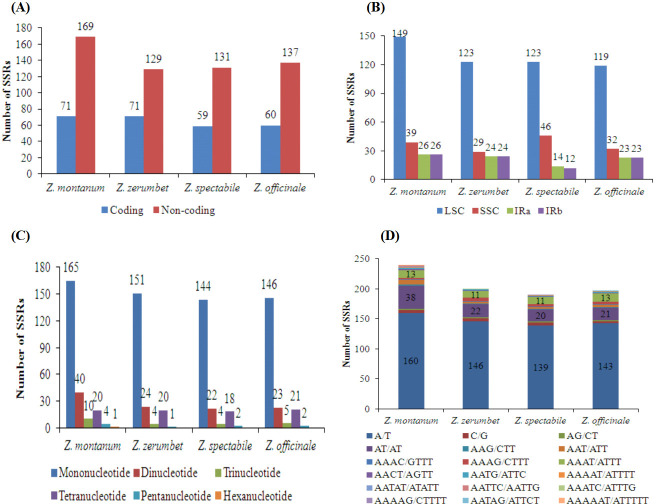

SSRs, with a repeat unit length ranging from one to six nucleotides or more, are widely distributed in chloroplast genomes [15–18, 21]. A total of 240, 200, 190 and 197 SSRs were detected in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum, Z. zerumbet, Z. spectabile, and Z. officinale, respectively (Fig 5A and S8 Table). Among these SSRs, the noncoding region had the most SSRs (129–169 loci, 64.50%-70.41%), whereas the coding region had the fewest SSRs (59–71 loci, 29.59%-35.50%) (Fig 5A). The majority of SSRs were located in the LSC regions (119–149 loci, 60.40%-64.73%); only a small portion were located in the SSC regions (29–46 loci, 14.50%-24.21%) and IR regions (12–26 loci, 6.31%-11.67%) of the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes (Fig 5B). Mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and penta-nucleotide SSRs were all detected in the four chloroplast genomes (Fig 5C). Additionally, only one hexanucleotide SSR was detected in the chloroplast genome of Z. montanum (Fig 5C). Among the different types of SSRs, mononucleotide repeats were the most abundant, accounting for 68.75%-75.78% of all SSRs, followed by dinucleotide (11.57%-16.66%) and tetranucleotide (8.33%-10.65%) repeats (Fig 5D and S8 Table). Mononucleotide SSRs were especially rich in A/T repeats (96.52%-97.94%) among the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes (Fig 5D). These results were consistent with most reported Zingiberaceae species [15–18, 21]. The second most abundant SSR types were AT/AT repeats, which were the majority of dinucleotide repeats (90.90%-95.00%). AAAT/ATTT repeats were the third most abundant SSR types in the four chloroplast genomes (55.00%-65.00%) (Fig 5D).

Fig 5. Comparison of simple sequence repeats among four chloroplast genomes of Zingiber species.

(A) SSRs distribution between coding and noncoding regions detected in the four Zingiber species chloroplast genomes. (B) Frequencies of identified SSRs in LSC, SSC and IR regions. (C) Number of different SSR types detected in four Zingiber species chloroplast genomes. (D) Frequency of identified SSRs in different repeat class types.

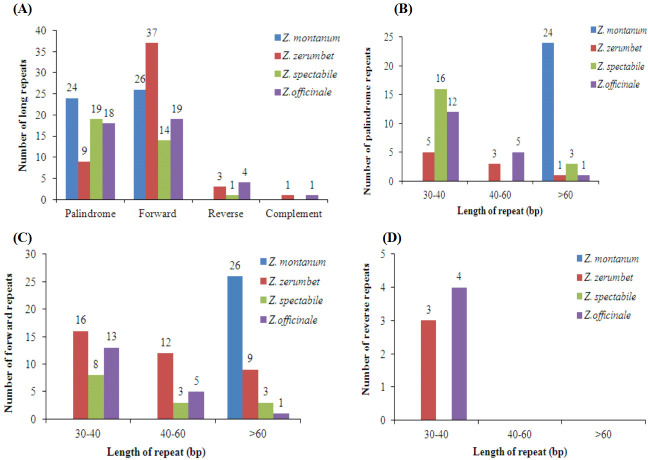

We also analyzed long repeats by REPuter and found the following four categories of long repeats: palindromic, forward, reverse, and complement. A total of 176 long repeats were found among the four chloroplast genomes. In detail, there were 50 (24 palindromic and 26 forward), 50 (9 palindromic, 37 forward, 3 reverse and 1 complement), 34 (19 palindromic, 14 forward and 1 reverse) and 42 (18 palindromic, 19 forward, 4 reverse, and 1 complement) long repeats in Z. montanum, Z. zerumbet, Z. spectabile and Z. officinale, respectively (Fig 6A and S9 Table). Interestingly, there were no complement repeats in the chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. spectabile (Fig 6A). With 24 palindromic repeats, Z. montanum contained the highest number of palindromic repeats, while Z. zerumbet contained the highest number of forward repeats at 37; Z. officinale contained 4 reverse repeats, the highest among the four compared chloroplast genomes (Fig 6B–6D). Palindromic and forward repeats measuring > 60 bp were found to be the most common in the chloroplast genome of Z. montanum (Fig 6B and 6C). Conversely, 30–60 bp palindromic and forward repeats were the most common in the other three chloroplast genomes (Fig 6B and 6C). Furthermore, almost all of the reverse repeats were less than 60 bp in the four chloroplast genomes (Fig 6D).

Fig 6. Analysis of long repeat sequences in the chloroplast genomes of the four Zingiber species.

(A) Total of four long repeat types; (B) frequency of palindromic repeats by length; (C) frequency of forward repeats by length; and (D) frequency of reverse repeats by length.

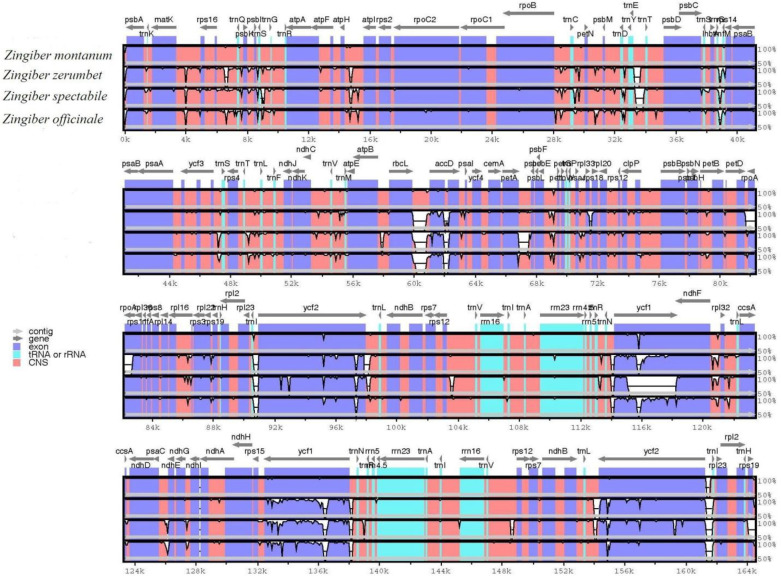

Comparative genomic analysis

The whole chloroplast genomes of the two sequenced Zingiber species and two published Zingiber species were compared using mVISTA, with Z. montanum being used as the reference (Fig 7). The mVISTA results indicated that the LSC and SSC regions were more divergent than the two IR regions. This phenomenon also occurred in most land plants [15–18]. The divergence level of the noncoding regions was higher than that of the coding regions. Approximately 13 highly divergent regions were found in mVISTA, and they were mainly distributed in noncoding regions, including start-psbA, trnfM-CAU-rps14, ycf1-ndhF, rbcL-accD, accD-psaI, atpI-atpH, ccsA-ndhD, rps18-rpl20, and trnE-UUC-trnT-UGU, and in 4 genes, namely, ycf1, ycf2, accD, and rps19 (Fig 7). Among these regions, accD-psaI, atpI-atpH, ccsA-ndhD, trnE-UUC-trnT-UGU, ycf1, and ycf2 have also been observed in other Zingiberaceae plant chloroplast genomes [15–18, 20]. Furthermore, the four junctions of LSC/IRa, LSC/IRb, SSC/IRa and SSC/IRb for the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes are shown in a detailed comparison (S1 Fig). In the four junctions, the genes in the border regions, including rpl22, rps19, Ψycf1, ndhF, ycf1, rps19, and psbA, were the same in Z. montanum, Z. zerumbet, and Z. officinale. However, in Z. spectabile, the trnM- ycf2 sequence was located in the junctions of the LSC/IRa region, which was missing the rpl22 and rps19 genes. The trnH gene was at one end of the IRb region in Z. spectabile instead of the rps19 gene in the LSC/IRb junction.

Fig 7. Sequence alignment of the four Zingiber chloroplast genomes in mVISTA.

The chloroplast genome of Z. montanum was used as a reference. Gray arrows and thick black lines above the alignment indicate gene orientation. Purple bars represent exons, sky-blue bars represent transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and red bars represent noncoding sequences (CNS). The horizontal axis indicates the coordinates within the chloroplast genome. The vertical scale represents the identity percentage ranging from 50% to 100%. White represents regions with sequence variation among the four species.

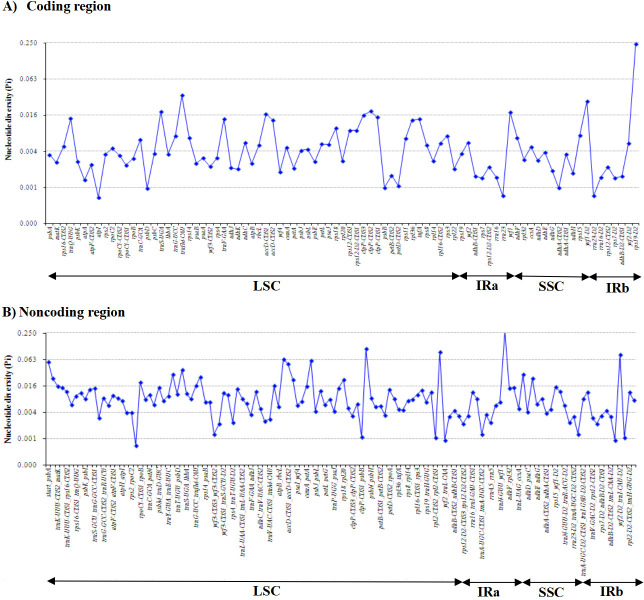

Moreover, the four Zingiber species were detected to have highly divergent regions in their chloroplast genomes using DnaSP by sliding window analysis (Fig 8). Among the 85 protein-coding regions (CDS), nucleotide diversity (Pi) values ranged from 0.0006 (atpI) to 0.2394 (rps19) and had an average value of 0.0084. Three protein-coding regions (ycf1, trnfM-CAU, and rps19) showed remarkably high values (Pi>0.02; Fig 8A and S10 Table). For the 128 noncoding regions, Pi values ranged from 0.00069 (rpoC1-CDS2-rpoC1-CDS1) to 0.2777 (ycf1-ndhF) and had an average of 0.01406. These results also proved that the average value of Pi in the noncoding regions was more than 1.5 times that in the coding regions. Sixteen of these regions had remarkably high values (Pi>0.0215), including rps18-rpl20, accD-psaI, psaC-ndhE, psbA-trnK-UUU, trnfM-CAU-rps14, trnE-UUC-trnT-UGU, ccsA-ndhD, psbC-trnS-UGA, start-psbA, petA-psbJ, rbcL-accD, ycf2-trnI-CAU, accD-CDS1-accD-CDS2, trnI-CAU-ycf2, psbT-psbN and ycf1-ndhF (Fig 8B and S10 Table). However, for the selection of effective and useful markers, both the length and Pi values of the highly variable regions must be considered. Among the nineteen regions, six regions (trnfM-CAU, accD-CDS1-accD-CDS2, ycf2-trnI-CAU, trnI-CAU-ycf2, psbT-psbN and ycf1-ndhF) were too short to be used as molecular markers. Finally, the other thirteen highly divergent regions could be suitable DNA markers for species identification in the genus Zingiber.

Fig 8. Sliding window analysis of the whole chloroplast genomes among four Zingiber species.

Window length: 800 bp; step size: 200 bp. X-axis: position of the window midpoint.

Selection events in unique protein-coding genes

The Ka/Ks ratio is useful for measuring selection pressure on a specific gene [48–50]. In most cases, the Ka/Ks ratio is less than 1, indicating a purifying selection; when Ka/Ks = 1, it reveals a neutral selection; and if Ka/Ks>1, it means a positive selection on the specific gene [48–50]. In this study, we compared the Ka/Ks ratios of 78 shared unique protein-coding genes in the Z. montanum chloroplast genome and the chloroplast genomes of the following three other related Zingiber species: Z. officinale, Z. spectabile, and Z. zerumbet (S2 Fig). The results indicated that the Ka/Ks values of some genes were NA or 50. These phenomena values occurred when the Ks values were notably low or the two aligned sequences exhibited 100% perfect matches. In these circumstances, we replaced NA or 50 with 0. As a result, ATP synthase (atpA and atpB), RNA polymerase (rpoA), small subunit ribosomal protein (rps3) and other protein-coding genes (accD, clpP, ycf1, and ycf2) with Ka/Ks>1 were detected, indicating that these genes were undergoing positive selection (S2 Fig). Moreover, the Ka/Ks ratios of three genes (clpP, ycf1 and ycf2) in three pairwise comparisons of Z. montanum-Z. officinale, Z. montanum-Z. spectabile, and Z. montanum-Z. zerumbet, respectively, were all >1, indicating that the three genes clpP, ycf1 and ycf2 exhibited critical adaptation evolution to diverse environments.

Inferring phylogeny in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae

The chloroplast genome sequences provided useful genomic resources for phylogenetic studies [51, 52]. Several previous studies have successfully used protein-coding genes, whole chloroplast genome sequences, or chloroplast SNP-based matrices for phylogenetic inference in the family Zingiberaceae [13, 15–26]. In the present study, a phylogenetic tree was reconstructed with a chloroplast SNP matrix from 31 chloroplast genomes using the ML method with C. pulverulentus, C. viridis and C. indica as outgroups. As shown in Fig 9, plants belonging to six genera from the family Zingiberaceae were basically divided into the following two clusters with high bootstrap values of 100%: one included two genera, Amomum and Alpinia, and the other included four genera, Curcuma, Hedychium, Kaempferia and Zingiber. The chloroplast SNP-based phylogeny analyses also showed that Zingiber was a monophyletic genus that was sister to the genus Kaempferia with moderate bootstrap values of 79% (Fig 9). In the genus Zingiber, Z. spectabile and Z. zerumbet were grouped in a sister branch with high bootstrap values of 100% and then clustered step by step with Z. montanum and Z. officinale with high bootstrap values of 100% (Fig 9). Interestingly, Z. zerumbet first grouped with Z. spectabile, rather than Z. montanum. Nevertheless, our molecular phylogeny analyses were congruent with a previous AFLP-based DNA marker study, which showed that Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet were phylogenetically closer to each other than to Z. officinale [14]. Our findings also confirmed that chloroplast SNPs were useful resources for phylogenetic analyses in the genus Zingiber and family Zingiberaceae.

Fig 9. Phylogenetic relationships constructed with SNPs from 31 chloroplast genomes using the maximum likelihood method.

The bootstrap values were based on 1,000 replicates and are indicated next to the branches.

Conclusions

We sequenced and analyzed the complete chloroplast genomes of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet from the family Zingiberaceae. The genome structures, gene information, amino acid frequencies, codon usage patterns and RNA editing sites of the two Zingiber species were determined. Comparative chloroplast genome analyses of Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet detected 489 SNPs and 172 indels. A total of 827 SSRs and 176 long repeats were identified in four Zingiber species chloroplast genomes. Thirteen divergent regions (ycf1, rps19, rps18-rpl20, accD-psaI, psaC-ndhE, psbA-trnK-UUU, trnfM-CAU-rps14, trnE-UUC-trnT-UGU, ccsA-ndhD, psbC-trnS-UGA, start-psbA, petA-psbJ, and rbcL-accD) were identified and might be useful for future species identification and phylogeny analysis in the genus Zingiber. Selection pressure analysis in the genus Zingiber indicated that the atpA, atpB, rpoA, rps3, accD, clpP, ycf1, and ycf2 genes were under positive selection. The chloroplast SNP-based phylogeny analyses determined that Zingiber was a monophyletic sister branch to Kaempferia and that phylogenetic relationships of the four Zingiber species could be clearly identified.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLS)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Ψ, pseudogenes. Boxes above the main line indicate the adjacent border genes. The figure is not to scale with respect to sequence length and shows relative changes only at or near the IR/SC borders.

(DOCX)

Ka, nonsynonymous; Ks, synonymous; Zm, Z. montanum; Zo, Z. officinale; Zs, Z. spectabile; Zz, Z. zerumbet.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

We deposited the raw Illumina and PacBio reads into the NCBI. The Z. montanum chloroplast sequencing data have SRA numbers SRR8185396 and SRR8184511. The Z. zerumbet chloroplast sequencing data have SRA numbers SRR8185094 and SRR8184512. The final assembled chloroplast genomic sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MK262727 and MK262726 for Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet, respectively. The bioproject number is PRJNA498576. We have also added the bioproject number in the manuscript. At this time, we declare that once this manuscript has published, all these relevant data were as soon as relieved from GenBank database.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (No.201607010101), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31501788), Guangdong Science and Technology Project (No.2015A020209078) and the special financial fund of Foshan--Guangdong Agricultural Science and technology demonstration city project in 2019.

References

- 1.Wu D, Larsen K. Zingiberaceae vol 24 Flora of China. Science Press, Beijing, China, 2000; pp 322–377. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu D, Liu N, Ye Y. The Zingiberaceous resources in China. Huazhong university of science and technology university press, Wuhan, China, 2016; pp 143. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branney TME. Hardy Gingers: including Hedychium, Roscoea and Zingiber; Timber Press, Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 2005; pp. 44–45, 230, 241–242. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao JY, Xia YM, Huang JY, Li QJ. ZHONGGUO JIANGKE HUAHUI, Science press, Beijing, China, 2006; pp 40, 41,43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ai TM, Dai LK. ZHONGUO YAOYONG ZHIWUZHI, Volume 12, Peking university medical press, Beijing, China, 2013; pp 400–415. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamir K, Seshagirirao K. Purification, biochemical characterization and antioxidant property of ZCPG, a cysteine protease from Zingiber montanum rhizome. Int J Biol Macromol 2018; 106, 719–729. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma RS, Joshi N, Padalia RC, Singh VR, Goswami P, Verma SK, et al. Chemical composition and antibacterial, antifungal, allelopathic and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of cassumunar-ginger. J Sci Food Agric 2018; 98: 321–327. 10.1002/jsfa.8474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddique H, Pendry B, Rahman MM. Terpenes from Zingiber montanum and their screening against muti-drug resistant and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2019; 24: 385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhtar NMY, Jantan I, Arshad L, Haque MA. Standardized ethanol extract, essential oil and zerumbone of Zingiber zerumbet rhizome suppress phagocytic activity of human neutrophils. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019; 19: 331 10.1186/s12906-019-2748-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreira da Silva T, Pinheiro CD, Puccinelli Orlandi P, Pinheiro CC, Soares Pontes G. Zerumbone from Zingiber zerumbet (L.) smith: a potential prophylactic and therapeutic agent against the cariogenic bacterium Streptococcus mutans. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018; 18: 301 10.1186/s12906-018-2360-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadabadi HK, Vaez-Mahdavi MR, Kamalinejad M, Shariatpanahi SS, Ghazanfari T, Jafari F. Pharmacological and biochemical properties of Zingiber zerumbet (L.) Roscoe ex Sm. and its therapeutic efficacy on osteoarthritis of knee. J Family Med Prim Care 2019; 8: 3798–3807. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_594_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jantan I, Haque MA, Ilangkovan M, Arshad L. Zerumbone from Zingiber zerumbet inhibits innate and adaptive immune responses in Balb/C mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019; 73: 552–559. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kress WJ, Prince LM, Williams KJ. The phylogeny and a new classification of the gingers (Zingiberaceae) evidence from molecular data. Am. J. Bot. 2002; 89: 1682–1696. 10.3732/ajb.89.10.1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh S, Majumder PB, Sen Mandi S. Species-specific AFLP markers for identification of Zingiber officinale, Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet (Zingiberaceae). Genet Mol Res 2011; 10: 218–229. 10.4238/vol10-1gmr1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Y, Chen X, Nie L, Sun W, Hu H, Lin Y, et al. Comparison and phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast genomes of three medicinal and edible Amomum species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019; 20: 4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li DM, Zhao CY, Liu XF. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Kaempferia galanga and Kaempferia elegans: molecular structures and comparative analysis. Molecules 2019; 24: 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li DM, Zhu GF, Xu YC, Ye YJ, Liu JM. Complete chloroplast genomes of three medicinal Alpinia species: genome organization, comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationships in family Zingiberaceae. Plants 2020; 9: 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui Y, Nie L, Sun W, Xu Z, Wang Y, Yu J, et al. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in the family Zingiberaceae based on the complete chloroplast genome. Plants 2019; 8: 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Deng J, Li Y, Gao G, Ding C, Zhang L, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Curcuma flaviflora (Curcuma). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2016; 27: 3644–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu M, Li Q, Hu Z, Li X, Chen S. The complete Amomum kravanh chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the commelinids. Molecules 2017; 22: 1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao B, Yuan L, Tang T, Hou J, Pan K, Wei N. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Alpinia oxyphylla Miq. and comparison analysis within the Zingiberaceae family. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0218817 10.1371/journal.pone.0218817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li DM, Xu YC, Zhu GF. Complete Chloroplast genome of the plant Stahlianthus involucratus (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019; 4: 2702–2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li DM, Zhao CY, Zhu GF, Xu YC. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Hedychium coronarium. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019; 4: 2806–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li DM, Zhao CY, Xu YC. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Curcuma longa (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019; 4: 2974–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li DM, Zhao CY, Zhu GF, Xu YC. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Amomum villosum. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019; 4: 2673–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li DM, Zhu G F, Xu YC, Ye YJ, Liu JM. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Curcuma zedoaria (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2020; 5: 1329–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, DePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011; 76: 273–297. 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunkard JO, Runkel AM, Zambryski PC. Chloroplast extend stromules independently and in response to internal redox signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015; 112: 10044–10049. 10.1073/pnas.1511570112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: Diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016; 17: 134 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chomicki G, Renner SS. Watermelon origin solved with molecular phylogenetics including Linnaen material: another example of museomics. New Phytol. 2015; 205: 526–532. 10.1111/nph.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Hu Z, Lin X, Li Q, Gao H, Luo G, et al. High-throughput pyrosequencing of the complete chloroplast genome of Magnolia officinalis and its application in species identification. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2012; 47: 124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-end de novo assembler. Gigascience 2012; 1: 18 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stoneshavas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012; 28: 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaisson MJ, Tesler G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): application and theory. BMC Bioinformatics 2012; 13: 238 10.1186/1471-2105-13-238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denisov G, Walenz B, Halpern AL, Miller J, Axerlrod N, Levy S, et al. Consensus generation and variant detection by celera assembler. Bioinformatics 2008; 24: 1035–1040. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 2004; 20: 3252–3255. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowe TM, Chan PP. tRNAscan-SE On-line: search and contextual analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44: W54–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkw413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47: W59–W64. 10.1093/nar/gkz238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. Mega7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016; 33: 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mower JP. The PREP Suite: Predictive RNA editors for plant mitochondrial genes, chloroplast genes and user-defined alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37: W253–W259. 10.1093/nar/gkp337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018; 14: e1005944 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rambaut A. Se-Al: Sequence Alignment Editor; Version 2.0. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software (accessed on 30 September 2017).

- 43.MISA-Microsatellite Identification Tool. Available online: http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/ (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- 44.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29: 4633–4642. 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32: W273–W279. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1451–1452. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010; 8: 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z, Nielsen R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000; 17: 32–43. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin K, Zhang Y, Li Y, Du FK. Different natural selection pressures on the atpF gene in evergreen sclerophyllous and deciduous oak species: evidence from comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Quercus aquifolioides with other oak species. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2018; 19: 1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Zhang J, Li L, Gao L, Xu J, Yang M. Structural and comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Pyrus hopeiensis-“wild plants with a tiny population”-and three other Pyrus species. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2018; 19: 3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huo YM, Gao LM, Liu BJ, Yang YY, Kong SP, Sun YQ, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of four Allium species: comparative and phylogenetic analyses. Sci. Rep. 2019; 9: 12250 10.1038/s41598-019-48708-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li W, Zhang C, Guo X, Liu Q, Wang K. Complete chloroplast genome of Camellia japonica genome structures, comparative and phylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0216645 10.1371/journal.pone.0216645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]