Abstract

A substantial amount of research indicates precocious pubertal development is associated with delinquent behavior in girls. However, no clear consensus on theoretical mechanisms underlying this association has been established. Using a prospective panel study of 480 African American girls, the current study uses latent growth curve analysis to compare two competing models—context of risk (CR) and life history (LH) theory—offering potential explanations of this phenomenon. The CR model suggests that early pubertal development substantially shapes girls’ social worlds such that they are exposed to more risk factors for delinquency; whereas, LH theory argues environmental unpredictability and harshness in childhood cause accelerated physical development, which predicts risky behavior. Results indicate that girls with precocious pubertal timing have more deviant peers and are exposed to harsher parenting, and that risk factors do not predict pubertal timing, providing more support for the CR model. Implications and future directions for research are discussed.

Keywords: Puberty, Pubertal Timing, Life History Theory, Context of Risk, Delinquency

A significant amount of empirical evidence suggests that precocious pubertal development is associated with externalizing behaviors in youth (Ge, Brody, Conger, & Simons, 2006; Haynie, 2003). In a recent meta-analysis, Dimler and Natsuaki (2015) found a modest but statistically significant mean correlation between pubertal timing and externalizing behavior (r = 0.123), although studies that examined concurrent effects reported significantly stronger associations than longitudinal investigations. The authors of this review note that important questions remain regarding the mechanisms whereby pubertal timing influences behavior and how long this effect lasts (Dimler & Natsuaki, 2015). The present study strives to address these issues.

Although there have been some studies focusing on deviant and delinquent outcomes of earlier pubertal timing (e.g. Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1993; Felson & Haynie, 2002; Haynie, 2003; Jackson, 2012), the majority of the empirical research examining the link between puberty and externalizing behavior has come from the fields of human development and psychology (e.g. Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murry, 2002; L. G. Simons, Sutton, Simons, Gibbons, & Murry, 2016). This body of research has developed a range of models explaining the connection between precocious somatic development and deviant behavior. We examine two models that arguably are the most relevant for criminology, the context of risk (CR) model (Haynie, 2003) and life history (LH) theory (Belsky, Schlomer, & Ellis, 2012; Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991). Puberty has been identified as an important sensitive period—particularly for girls—in which expectations and social relationships are dramatically reshaped (Obeidallah, Brennan, Brooks-Gunn, Kindlon, & Earls, 2000). Indeed, prior research has suggested that puberty may be an essential developmental stage in the development of various psychopathologies generally (Mendle, 2014b) and externalizing and delinquent behaviors particularly (Haynie, 2003).

The focus of the present study is limited to girls and young women. We have two reasons for this decision. First, initial research in both the LH and CR models focused on how girls who experience precocious development are at risk for externalizing problems (Ellis, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999; Haynie, 2003). Because these initial formulations examined mechanisms and social processes that are likely unique to girls (e.g. earlier development of secondary sexual characteristics may lead to increased attention from older and more delinquent boys), one would expect a theoretical model connecting boys’ pubertal timing and delinquency to be substantially different (Mendle & Ferrero, 2012). Second, as many have noted (Broidy & Agnew, 1997; Carbone-Lopez & Miller, 2012; Kaufman, 2009), there is a need for more research on the etiology of women’s antisocial behavior as the field of criminology devoted most of its attention to males. The present study investigates competing models of the processes whereby precocious pubertal development increases girls’ and young women’s risk for delinquency.

Theory

A substantial literature has linked earlier pubertal timing to increased delinquency and other externalizing behaviors among girls (e.g. Ge, et al., 2002; Haynie, 2003; Najman et al., 2009). Previous studies have implicated parenting behaviors (Mrug et al., 2008) and peer delinquency (Mrug et al., 2014) as potentially important factors explaining this association. However, no consensus has emerged on the theoretical mechanisms underlying these associations. Two substantially different theoretical explanations have been proffered, each proposing conflicting processes to explain these phenomena.

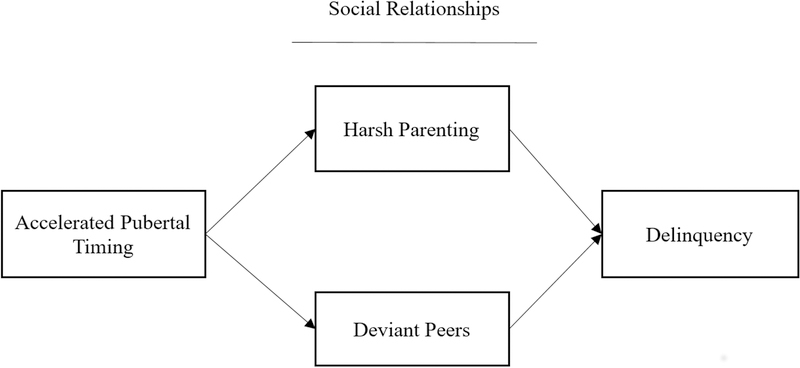

The CR model, first developed by Haynie (2003), argues that early pubertal development substantially shapes girls’ social worlds such that they are exposed to more risk factors for delinquency including harsh parenting and delinquent peer context. Alternatively, LH theory argues that girls will physically develop faster as a response to signals (discussed below) of environmental harshness and uncertainty (Ellis, 2004). As part of this developmental process, girls exposed to harsh and uncertain environment will develop behavioral proclivities associated with delinquent behavior (Dunkel, Mathes, & Beaver, 2013). These theoretical perspectives are elaborated below.

Context of Risk Model

The CR model identifies a set of family and peer related mechanisms that link pubertal timing to a girl’s risk for delinquency. Haynie (2003) argues that the social worlds of girls who begin puberty early are significantly different from those who begin later. Puberty is an influential sensitive period for all children, but especially for girls, as their physical maturity manifests in particularly noticeable ways. Haynie argues that precocious pubertal development is a potent risk factor for delinquency among girls because they are treated differently by parents and peers. Specifically, girls who develop faster have worse relationships with their parents, are monitored less by parents, are more likely to spend time with deviant peers, and are more likely to be dating an older boy. These social arrangements increase the chances that girls who develop early will engage in delinquent behavior and experience sexual victimization (Haynie & Piquero, 2006).

Parenting

Pubertal development in girls is accompanied by highly visible signs of physical maturation (e.g. breast development, hair growth). When these signs appear earlier than expected, parents may respond by (consciously or unconsciously) altering their behavior toward their daughter in an attempt to address concerns about the implications of these changes (Haynie 2003). Conversely, in response to both hormonal changes and social environmental changes (e.g., attention from boys), early maturing girls are likely to press for increased privileges, more time out with peers, expanded curfews, and the freedom to date. The prospect of their daughter’s movement into such activities is apt to exacerbate parental impulses to protect and maintain their daughter’s sexual innocence (Haynie 2003; Steffensmeier & Allan 1996). The result of this dynamic is expected to lead to increased parent-child conflict and deterioration of the parent-child relationship. Parents are likely to adopt harsher and more restrictive management strategies while their daughter pulls away, seeks more time away from the home, invests more time with peers, and becomes less open to parental influence. Thus, according to Haynie (2003), early puberty has a corrosive effect on the parent-daughter relationship which includes increased parental hostility and restrictiveness. These changes in parental behavior are seen, in turn, as elevating the young girl’s risk for delinquent behavior.

Peers

Haynie (2003) also argues that girls who experience accelerated pubertal development are at risk for involvement in a peer group consisting of older and more deviant individuals. This differential peer association is seen as a consequence of three social processes. First, early maturing girls may seek time away from home given the increased parental hostility and restrictiveness described above. The peer group becomes their primary socializing agent as they strive to avoid parental control and increase affiliation with their friends (R. L. Simons, Simons, Chen, Brody, & Lin, 2007). Second, building on Moffitt’s dual taxonomy theory (1993), Haynie argues that early maturing girls tend to be attracted to more mature social roles and identities. They experience a “maturity gap” in which they are treated as children by their parents and other adults based on their temporal age, while their physical appearance and hormone changes cause them to seek a more independent, grownup status. This desire to engage in adult-like behaviors leads these girls to associate with peers who engage in deviant, pseudomature behaviors such as substance use, partying, and sexual experimentation. Third, Haynie (2003) notes that early maturing girls attract the attention of older boys. They often end up dating or forming romantic relationships with these older boys who have later curfews and are experimenting with adult-like behaviors (Simmons, Blyth, Van Cleave, & Bush, 1979).

Thus, whether they are escaping from harsh, controlling parents, seeking out more adult-like roles and activities, or responding to the attention of older boys, Haynie argues girls who experience accelerated puberty tend to be involved in a more delinquent peer group. Indeed, a profusion of studies has shown that affiliation with deviant peers is one of the most powerful predictors of increased participation in delinquent behavior (e.g. Akers, 1998; Warr, 2002) explains why peer group may link pubertal timing to delinquency. As with hostile parenting behaviors, the CR hypothesis suggests that precocious pubertal development will occur before girls enter delinquent peer groups, and that peer delinquency will mediate the relationship between pubertal timing and later delinquency.

Life History Theory

Life history theory uses evolutionary theory to explain the link between a harsh and unpredictable environment in childhood and risky behavior in childhood and adolescence (Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009). Organisms are more evolutionarily successful when future generations are comprised of a larger share of their offspring. To this end, organisms that survive longer and reproduce more are more successful than others. However, organisms have limited resources to commit to developmental processes—e.g. growth, maintenance, and reproduction—and these processes are differentially adaptive in differing environments (Chisholm, 1993). Organisms in harsh and unpredictable environments are more reproductively successful when they reproduce early—before the environment has time to kill or disable them—and often—in case their offspring are killed by the harsh environment (Ellis et al., 2009). Given a constantly changing environment, phenotypic developments that might have been adaptive for the parents’ generation may not be adaptive for their offspring. As fitness is essentially dependent on concordance between organism and environment, evolution might be expected to favor mechanisms that allow an organism to track its environment and develop particular traits in response to environmental cues (Belsky, Ruttle, Boyce, Armstrong, & Essex, 2015). Thus, LH theory posits that an organism’s rate of bodily development is not set from birth, but is sensitive to environment al cues of harshness and unpredictability.

LH theory suggests that organisms commit to a particular reproductive strategy that represents a series of these trade-offs. By committing resources to some and not to other processes, organisms are described as existing along a continuum of “speed” (Charnov, 1993). An organism develops a fast or slow LH strategy in response to environmental conditions (Chisholm, 1993). The central trade-off in LH theory is the timing of sexual development. According to the theory, individuals exposed to a dangerous and unpredictable environment grow-up fast. They manifest early puberty, produce a high number of offspring with minimal parental investment, and experience a short lifespan. Further, this reproductive strategy includes a collection of presumably adaptive traits such as a distrust of others and an opportunistic approach to life. This suite of reproductive and psychological traits is seen as increasing the chances of reproductive success in an unstable, hostile environment. In contrast, the theory posits that individuals reared in a safe and predictable environment will develop more slowly (i.e., later puberty) and demonstrate high parental investment in a relatively small number of offspring. Presumably, this reproductive strategy is more suited to life in a safe, stable environment in which individuals can rely on a long lifespan and a high offspring survival rate (Ellis, Shirtcliff, Boyce, Deardorff, & Essex, 2011). It is important to note that the term “strategy” is not meant to imply that individuals are actively surveying the social and physical environment and making calculated decisions about how to allocate resources. Rather, LH strategy is developed entirely subconsciously as neurological and somatic structures develop in response to environmental conditions (Ellis, et al., 2009).

Past research has provided support for some elements of LH theory. Studies of humans have found that environmental conditions in the first few years of life predict timing of puberty controlling for body weight (e.g. Ellis & Essex, 2007; Ellis, et al., 1999), which in turn predicts precocity and riskiness of sexual behavior (e.g. Davis & Werre, 2008; Kruger, Reischl, & Zimmerman, 2008), as well as mistrusting models of relationships (Del Giudice, 2009). These findings have been strongest among females (Ellis, 2004).

LH research identifies parenting as an essential indicator of environmental harshness (Belsky, et al., 2012; Ellis, et al., 2009). Young children spend a large amount of time with their parents, and to large extent, parents control what environments their children are exposed to. Greater parental investment in children has been shown to greatly improve survival chances (Ellis, 2004), therefore high quality parenting should encourage slower LH strategies. Empirical evidence largely supports this proposition (e.g. Belsky, et al., 2012; L. G. Simons, Sutton, et al., 2016).

LH theorists have proposed that direct exposure to crime and violence could also be a direct indicator of environmental harshness (Ellis et al., 2012). Seeing or hearing about violent behavior occurring in a child’s neighborhood would be an excellent indicator of how dangerous that neighborhood is. There is substantial evidence that children growing up in neighborhoods characterized by high levels of violence or with few living adult males develop faster LH strategies (e.g. Kruger, Aiyer, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2014; Wilson & Daly, 1997). A substantial body of research suggest that neighborhood conditions are particularly important for explaining the link between girls’ pubertal timing and violent behavior (Obeidallah, Brennan, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2004). Similarly, LH theory would suggest that interaction with highly deviant peers would increase an individual’s exposure to violent behavior and would generally serve as an effective indicator of environmental harshness.

Family financial instability is a potential indicator of environmental unpredictability. That is, if the amount of resources available is scarce or in constant flux, individuals will accelerate somatic development to reach development before the environment becomes harsher (Belsky et al., 2012; Ellis et al., 2009). Thus, living in a neighborhood characterized by concentrated disadvantage, unmet family material needs, and poverty status would likely indicate an environment where resources are scarce or unpredictable.

Most LH studies of humans have focused on elements of the LH decision chain that involve sex and reproduction (e.g. Belsky, et al., 2012; Ellis, 2004). Although some scholars have suggested that the LH model could explain a larger suite of behaviors that are considered risky (Dunkel, et al., 2013; Ellis, et al., 2012), relatively little work has been conducted linking childhood environment to pubertal timing and to behaviors other than sexual behavior. It has been argued, however, that LH strategy might be tied to a whole suite of risky behaviors, including delinquent and criminal behavior (e.g. Dunkel, et al., 2013; Figueredo et al., 2006; Wiebe, 2012). We have noted that LH theory posits that a fast reproductive strategy includes traits such as distrust, opportunism, and concern with immediate rewards. Importantly, research in criminology indicates that these characteristics increase the likelihood of delinquency and crime. Belsky, Steinberg, and Draper (1991) argue that a suite of psychological and behavioral developments (e.g. hostile internal model of relationships, aggressive and noncompliant behaviors) will occur through neurological development as part of a fast developmental strategy prior to (and potentially contributing to) early pubertal maturation. Scholars arguing that LH theory can be extended to criminal behavior generally argue that the association between childhood life circumstances and later delinquency and criminal behavior is a result of these psychological developments (Dunkel, et al., 2013). Because pubertal timing is suggested as a particularly important indicator of pubertal strategy, the association between childhood adversity and delinquency should be mediated by pubertal timing if this perspective is correct. In the LH model, the association between early adversity and later delinquent behavior should an epiphenomenon of an underlying developmental process, not a social process as suggested by the CR model.

There are, however, several theories in developmental psychology (attachment theory, hostile attribution bias) and criminology (social learning theory, self-control theory) that identify harsh parenting and affiliation with deviant peers as a cause of delinquency. These theories are more parsimonious than LH theory as they do not require the inclusion of biological variables. As proponents have noted, acceptance of LH theory over its competitors requires that it specify a prediction that cannot be accounted for by its competitors (Belsky et al., 2012). This is the case regarding the mediating effect of early puberty.

As discussed earlier, Haynie’s CR model (2003) also includes early puberty as a central factor in predicting girls’ delinquency. She posits that early puberty fosters increases in harsh parenting and affiliation with delinquent peers which, in turn, increase the risk for delinquency. Stated differently, harsh parenting and affiliation with deviant peers are viewed as mediators of the effect of early puberty on delinquency. LH theory identifies a different causal sequence. LH theory views early puberty as a consequence of harsh parenting and delinquent friends. Hence early puberty should mediate the effect of harsh parenting and delinquent friends on delinquency. Unlike the CR model, which is based on social relationships and may be sensitive to cultural and structural factors, LH theory purports to explain human nature, and these processes should not fundamentally vary across societies or cultures.

Previous Research

In initial tests of this model, Haynie reported that girls who score higher on an early puberty scale are more likely to engage in party deviance (e.g. smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, truancy), minor delinquency, and major delinquency (Haynie, 2003). She also found that most of the outcomes are mediated, at least in part, by the parenting and peer factors mentioned above (Haynie, 2003). Previous studies attempting to use the LH perspective to explain criminal behavior have failed to provide a definitive test. Dunkel, et al. (2013) attempted to directly integrate LH theory with Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory. Unfortunately, they used only cross-sectional data, which cannot establish causal ordering, and a convenience sample of college students, which cannot be used to make arguments about more disadvantaged populations. Criminal behavior, per se, was not actually assessed, but rather criminal intent, and LH strategy was measured using a scale assessing the cognitive correlates of a fast LH strategy, not an actual measure of pubertal timing. Similarly, van der Linden, Dunkel, Beaver, & Louwen (2015) found evidence of an association between LH strategy and criminal behavior. They argued that a “general personality factor”—which is very similar to Gottfredson and Hirschi’s low self-control and to the cognitive correlates used by Dunkel et al. (2013)—is the principal driver of variation in criminal behavior between persons. Like Dunkel et al., van der Linden et al. had no biological indicator of LH strategy, used cross sectional data, and used a sample of incarcerated prisoners. Thus, they selected their subjects based on the dependent variable as most persons are in prison for engaging in criminal behavior.

Though the research presented above is informative, methodological limitations related to measurement, sampling, and temporal ordering precludes reaching strong conclusions regarding the extent to which delinquency is a LH adaptation. The current study improves on previous research in the LH perspective by using 1) structural equation modeling which provides for formal mediation tests, 2) growth curve analysis which allows us to estimate duration of the effect, 3) longitudinal data which can help overcome time ordering issues, 4) a physical indicator of LH strategy in the form of pubertal timing assessed at two different waves, and 5) a prospective sample that includes respondents who both do and do not report engaging in the assessed criminal and delinquent behaviors.

Current Study

The goals of this study are to 1) test whether the mechanisms specified by the CR model or the LH model best accounts for the links among harsh environmental conditions, earlier pubertal development, and delinquent behavior, and 2) estimate the duration of this effect. To that end, we address the following issues:

First, we will assess the association between pubertal timing and delinquent behavior. Based on the meta-analysis of Dimler and Natsuaki (2015), we expect to find a modest relationship between the two variables. Second, we will investigate whether the effect of pubertal timing on delinquent behavior is mediated by harsh parenting and affiliation with deviant peers (i.e. the CR model). Third, we will examine whether the effects of harsh parenting and affiliation with deviant peers on delinquent behavior are mediated by pubertal timing (i.e. the life history model. Finally, we will estimate how long the effect of pubertal timing on delinquent behavior persists. This study is not intended as a complete test of either theoretical perspective presented here, but rather is designed to assess which model best explicates the links described in the first goal above.

Method

Data

We utilize data collected as part of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS). FACHS is a multisite longitudinal panel study of African American youths, their primary and secondary caregivers, and their romantic partners (R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011). Using census block groups, a representative stratified random sample of ten and eleven-year-old African American children living in Georgia and Iowa in 1998 (Wave 1) was collected. Repeat interviews were conducted in 2000 (Wave 2), 2002 (Wave 3), and 2005 (Wave 4). The mean age of respondents at Wave 1 was 10.56.

In the first wave of data, 897 (480 female) African American youths were surveyed along with their primary caregivers and secondary caregivers when available. As of Wave 4, 714 respondents remained yielding a retention rate of 80%. This sample contains a diverse range of respondents from a variety of different socioeconomic statuses (SES) and neighborhood conditions, including rural, suburban, and urban communities (R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011). Thus, these data are particularly useful for testing LH theories because they contain respondents from a variety of environmental conditions. FACHS is a longitudinal panel survey, making the data ideal for establishing time ordering and analyzing delayed and ongoing effects from the environment. For more on FACHS, see L. G. Simons, Sutton, et al. (2016). Because we are specifically concerned with girls’ offending, we only use female participants in this study. The final sample size for our analysis was 480. Importantly, there was no evidence of a retention bias as the young women who continued to participate in the study at Wave 4 did not differ from those who dropped out in terms of Wave 1 scores on caregiver SES, exposure to harsh parenting, neighborhood disadvantage, school achievement, delinquency, or affiliation with deviant peers. The current study uses data collected in Waves 1 through 4.

Measures

Delinquency

Delinquent behavior was assessed at Waves 2–4 using the conduct disorder scale contained in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (DISC-IV). This measure asks the respondent to report their participation in a range of deviant and antisocial acts during the preceding 12 months. The instrument focuses upon 13 delinquent acts, including bullying and intimidation, assault, use of a weapon, robbery, arson, and staying out late. This instrument has been used in several previous criminological studies (e.g. L. G. Simons, Wickrama, et al., 2016; R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011) and has been shown to be valid and reliable (Shaffer et al., 1993). Girls’ scores on this measure represent the number of delinquent acts that they engaged in over the prior year. Thus, this measure is a count variable.

Pubertal Timing

Pubertal timing is the extent to which a child has developed certain traits related to puberty in comparison with his or her peers. Those who have advanced further—or have completed puberty earlier—than their peers in this development can be considered to have earlier timing (L. G. Simons, Sutton, et al., 2016). The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) was used to assess pubertal timing in the current study (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). This 6-item scale asks respondents on a scale of 1 (have not begun) to 4 (development completed) how much they have developed within the past 12 months with regards to body hair growth, growth spurt, voice changes, breast development, and skin changes. A high score indicates further development, and thus earlier timing. This measure has been used in previous studies and has been found to be reliable and accurate (e.g. Ge, Brody, Conger, & Simons, 2006; Ge, et al., 2002; Kogan et al., 2014). Self-reported measures of perceived pubertal development have been suggested as particularly valuable for assessing social outcomes like delinquency, as one’s perception of one’s own pubertal timing is expected to shape behaviors and perceptions of self (Mendle, 2014a). This measure is assessed at Waves 1 and 2.

Deviant Peers

Affiliation with a deviant peer group was assessed at Waves 1 and 2 using a 12-item scale composed of questions asking in the past 12 months how many of the respondent’s close friends engaged in various deviant behaviors including stealing something worth less than $25, stealing something worth more than $25, motor vehicle theft, assault, assault with a weapon, robbery, tobacco use, alcohol use, inhalant use, any drug use, binge drinking, becoming pregnant or impregnating someone. Possible responses are (1) none of them (2) some of them (3) all of them. Scores were averaged across the 12 items. Cronbach’s alpha values for Waves 1 and 2 were 0.82 and 0.84 respectively.

Harsh Parenting

Harsh parenting was assessed at Waves 1 and 2 using an 11-item scale developed by Conger and Elder (1994) that focuses upon parental behavior during the previous 12 months. Six of the items focus upon parental hostility and rejection (e.g., How often does your primary caregiver shout or yell at you? How often does your primary caregiver call you bad names?), and five items focus upon warmth and support (e.g., How often does your primary caregiver tell you they love you? How often does your primary caregiver help you do something that is important to you?). This instrument has been shown to have high reliability and validity (L. G. Simons, Sutton, et al., 2016; R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011). Response format ranged from 1 (always) to 4 (never). Scores for each item were standardized, and these values were then averaged. Responses were coded so that a higher score on this measure indicated harsher parenting. Cronbach’s alpha was .74 and .81 at Waves 1 and 2 respectively.

Victimization of Self and Household

At Wave 1, target youths were asked if anyone had ever “used violence, such as in a mugging, fight, or sexual assault, against you or any member for your household anywhere in your neighborhood?” during the time that they had lived in their current neighborhood. They then indicated how many times they or any member of their household had been victimized. 395 girls responded that they or members of their household had never been victimized. The mean number of victimization incidents reported was 0.65.

Concentrated Disadvantage

Concentrated disadvantage in respondents’ neighborhoods was assessed at Wave 1 using a combination of instruments from the 2000 census suggested by Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997). The proportion of total unemployed persons over 16, the proportion of households below the poverty level, the proportion of households on public assistance, and the percentage of single mother headed household in a respondent’s census block group were standardized and averaged to create a concentrated disadvantage score for 2000. Census measures are more objective indicators of disadvantage because they were 1) collected outside of the FACHS project and 2) are not based on self-report by FACHS respondents. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.83.

Exposure to Crime

Exposure to crime was assessed at Wave 1 using a six-item scale developed for the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Target youths reported how often in the past six months in their neighborhood there was a violent criminal incident including “a fight in which a weapon like a gun or knife was used,” “a gang fight,” and “a robbery or mugging” with scores ranging from (1) never to (3) often. Responses on the six items were averaged to create this scale. The means score on this measure was 1.40, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71.

Unmet Material Needs

Primary caregivers reported their material needs using a six-item scale developed for the Iowa Youth and Families Project (Conger & Elder, 1994). Items included “My family has enough money to afford the kind of home we need” and “we have enough money to afford the kind of medical care we need” with responses ranging from (1) strongly agree to (4) strongly disagree and “During the past 12 months, how much difficulty have you had paying your bills?” with responses ranging from (1) no difficulty at all to (5) a great deal of difficulty. Responses were averaged to create the final scale. The mean score was 2.47, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

Poverty

Primary caregivers reported their household income and the number of people living in their household at Wave 1. Girls in households that fell below the federal poverty line at Wave 1 were coded as “1” on this measure, while all other girls were coded as “0”. 243 respondents lived in households that fell below the federal poverty line at Wave 1.

Controls

This study controls for potential confounds that have been identified in the literature including prior delinquent behavior assessed at Wave 1 using the same scale as at other waves, target low self-control at Wave 1 assessed using a measure derived from Kendall and Wilcox (1979) and used in several previous criminological applications (e.g. L. G. Simons, Sutton, et al., 2016; R. L. Simons & Burt, 2011), target age at Wave 1, primary caregiver educational attainment at Wave 1 (single indicator CFA is used to preserve cases, see Byrne, 2012; R. L. Simons, Burt, Barr, Lei, & Stewart, 2014), and primary caregiver criminal behavior measured at Wave 1.

Analytic Method

All analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). We utilize Latent Growth Curve Modeling (LGCM) in the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) framework (Wickrama, Lee, O’Neal, & Lorenz, 2016). LCGM can be used to evaluate trajectories for individuals on variables that are measured repeatedly over time. Mplus generates latent variables representing an individual’s initial level and the slope of her trajectory on a given variable. A linear relationship could be estimated for a variable y for person i at time t using the following equation:

| 1 |

where and represent person i’s intercept and slope respectively (Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006). These individual slopes can then be aggregated to generate a population level variable with a mean (γ) and variance (ε) that can be correlated in SEM models in the same way as other latent variables. These variables are estimated using transformed log rate ratios with incident thresholds (τ) using the following equation:

| 2 |

The means of the initial level and slope variables can be predicted by exogenous variables (X):

| 3 |

| 4 |

where γ0 is the mean initial level and γ1 is the mean slope. Thus, the predicted incident rate for individual i at time t can be expressed as:

| 5 |

Because it is the central variable in this study, values for pubertal timing are estimated using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Missing data are handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation with a Robust Maximum Likelihood estimator assuming data are missing at random.

In the current study, the repeated count variable delinquent behavior is used to construct latent growth curves. Raw scores on these measures are transformed using the “COUNT ARE” command in Mplus. Thus, estimates predicting mean intercept and slope variables in the model are incident rate ratios (Wickrama, et al., 2016). This analysis requires the use of an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. In terms of fit statistics, Mplus can only generate Pearson’s χ2, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) while using an EM algorithm (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). The first two of these statistics are used to assess fit. To generate other fit statistics, including Steiger’s root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990), and the square root mean residual (SRMR) (Hu & Bentler, 1998), a parallel model (not shown) was estimated without the “COUNT ARE” command. Thus in this parallel model, delinquent behavior is treated as continuous. When reported below, these indices represent this parallel model and are thus approximations of the fit of the principal model.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Beginning with bivariate correlations, shown in Table 1, most of the associations are in the expected direction. Delinquency at Wave 2 was positively and significantly correlated with delinquency at Waves 3 (r = .15, p < .05) and 4 (r = .20, p < .001), puberty factor scores at Waves 1 (r = .19, p < .001) and 2 (r = .10, p < .05), deviant peers at Waves 1 (r = .14, p < .01) and 2 (r = .37, p < .001), harsh parenting at Waves 1 (r = .22, p < .001) and 2 (r = .32, p < .001), victimization at Wave 1 (r = .15, p < .01), and exposure to crime at Wave 1 (r = .16, p < .01). It is notable that the strongest correlations between puberty score and delinquent behaviors are between puberty at Wave 1 and delinquency at Wave 1, followed by puberty at Wave 1 and delinquency at Wave 2. Pubertal timing factor scores at Wave 1 and 2 were also significantly correlated with each other (r = .84, p < .001), deviant peers at Wave 2 (r = .25, p < .001 and r = .25, p < .001, respectively), harsh parenting at Wave 2 (r = .21, p < .001 and r = .23, p < .001, respectively), and poverty (r = −.15, p < .01 and r = −.25, p < .01, respectively), though these relationships were negative. Puberty factor score at Wave 1 was correlated with unmet material needs at Wave 1 (r = .10, p < .05). Puberty score at Wave 2 was significantly correlated with harsh parenting at Wave 2 (r = .10, p < .05). These relationships are explicated further below in multivariate analysis.

Table 1.

Selected Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| I | Delinquency, w2 | − | |||||||||||||

| II | Delinquency, w3 | .15 * | − | ||||||||||||

| III | Delinquency, w4 | .20 *** | .15 ** | − | |||||||||||

| IV | Puberty Factor Score, w1 | .19 *** | .01 | −.05 | − | ||||||||||

| V | Puberty Factor Score, w2 | .10 * | .03 | .02 | .84 *** | − | |||||||||

| VI | Deviant Peers, w1 | .14 ** | .03 | −.03 | .05 | −.03 | − | ||||||||

| VII | Deviant Peers, w2 | .37 *** | .17 ** | .17 ** | .25 *** | .25 *** | .33 *** | − | |||||||

| VIII | Harsh Parenting, w1 | .22 *** | .14 | .06 | .08 | .10 * | .32 *** | .18 *** | − | ||||||

| IX | Harsh Parenting, w2 | .32 *** | .23 | .06 | .21 *** | .23 *** | .10 | .32 *** | .45 *** | − | |||||

| X | Victimization, w1 | .15 ** | .06 | .02 | .08 | .05 | .06 | .07 | .07 | .06 | − | ||||

| XI | Con. Disadv., 2000 | .03 | .03 | .07 | .03 | .02 | .08 | .11 * | .06 | .05 | .05 | − | |||

| XII | Exp. to Crime, w1 | .16 ** | −.02 | −.01 | .08 | .08 | .32 *** | .20 *** | .21 *** | .12 *** | .24 *** | .26 *** | − | ||

| XIII | Unmet Needs, w1 | .02 | −.05 | −.02 | .10 * | .06 | .02 | .10 | .04 | .13 | .03 | .13 ** | 12 ** | − | |

| XIV | Poverty, w1 | .09 | −.08 | −.03 | −.15 ** | −.25 ** | .09 | .01 | .09 | .14 | .07 | .13 * | .24 *** | .31 *** | − |

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

XI |

XII |

XIII |

XIV |

||

| Mean | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.32 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 1.40 | 2.47 | 0.36 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 2.26 | 0.83 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.48 |

Note: N = 480

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

SEM Results

We turn now to model fit indices. For the SEM depicted in Figure 4, the Pearson χ2 statistic is not significant (χ2 = 234.301, 202 d.f.; p > .05), indicating that the covariance matrix implied by the model presented here does not significantly differ from the observed matrix in the data. The sample size adjusted BIC is 24362.804. Fit statistics from the parallel model treating count variables as continuous all indicate excellent or acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.030; CFI = 0.920; SRMR = 0.035). These statistics all suggest that this model fits the data well.

Figure 4.

SEM Results

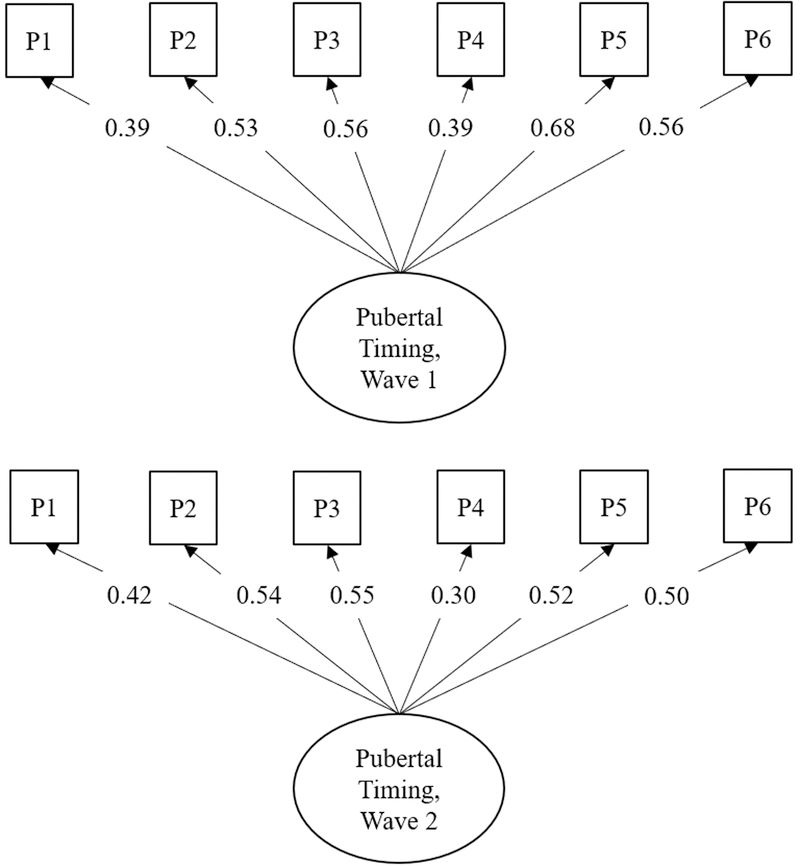

The measurement portions of the structural equation model, show in Figure 3, indicate that the pubertal timing items at both waves load reasonably well onto a latent factor. All factor loadings are statistically significant and all standardized loadings are at or above 0.3. Because none of the loadings are substantially higher or lower than the others, we argue that each item captures a unique substantial portion of the underlying concept of pubertal developmental timing (Byrne, 2012; Kline, 2016). It could be that using a latent variable to represent pubertal timing would inflate stability in this construct making it difficult to find other significant predictors (Lorenz, Conger, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1995). We also estimated a model (not shown) entering each respondent’s score on the PDS as a manifest variable and produced a nearly identical pattern of results.

Figure 3.

Measurement Portion for Waves 1 and 2 Pubertal Timing

Turning to the structural portion of the model, depicted in Figure 4 and Table 1, the standardized total effect of pubertal timing at Wave 1 on the average initial level of delinquent behavior for girls is 0.24 (p < 0.05). Girls who score higher on the pubertal timing scale—and therefore have developed faster than others in the study—at Wave 1 tend to have a higher initial level of delinquent behavior at Wave 2. The standardized total effect from pubertal timing to delinquency trajectory slope is −0.56 (p < .01). In contrast to findings for initial level, girls who score higher on the PDS tend to have more negative slopes than their peers in the sample controlling for other variables in the model.

Controlling for other covariates including Wave 1 deviant peer association, earlier pubertal timing at Wave 1 is associated with belonging to a more deviant peer group at Wave 2 (β = 0.14, p < .05). Deviant peer group at Wave 2 is associated with initial delinquent behavior (β = 0.40, p < .001). The specific indirect path from pubertal timing at Wave 1 to delinquent behavior intercept mediated by deviant peers at Wave 2 is significant and positive (β = 0.056, p < 0.05). This is evidence that girls who develop earlier engage in more delinquency initially, and that this relationship is mediated by peer group deviance.

Similarly, controlling for other variables in the model, the parents of girls with higher pubertal timing scores at Wave 1 engaged in more harsh and hostile behaviors at Wave 2 as reported by their daughters (β = 0.14, p < 0.05). Higher reported parental harshness at Wave 2 is associated with a higher delinquent behavior trajectory intercept (β = 0.22, p = 0.01). The specific indirect effect from pubertal timing at Wave 1 to initial level of delinquent behavior running through harsh parenting at Wave 2 is positive but only marginally significant (β = 0.030, p = 0.08). Thus, there is only weak evidence that the relationship between accelerated pubertal development and delinquency is mediated by parental behavior.

Next we turn to indicators of harsh and unpredictable environment. Paths from affiliation with deviant peers and harsh parenting at Wave 1 to pubertal timing at Wave 2 are not significant. Pubertal timing at Wave 2 does not significantly predict either initial level or trajectory slope of delinquent behavior. All significant effects that deviant peers and harsh parenting have on delinquency run through other variables (i.e. Wave 2 harsh parenting and deviant peers). The measure of pubertal timing is highly stable between waves (β = 0.64, p < .001). It could be that this stability so reduces the residual variance of pubertal timing at Wave 2 that there is little variance left to be explained by other variables. However, cross-sectional correlations of deviant peers and harsh parenting with pubertal timing at Wave 1 are not strong and are non-significant. Because these variables are largely unrelated both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, it is unlikely that there are substantive effects being masked by high stability.

As for other indicators of harsh and unpredictable environment, victimization at Wave 1 was related to initial delinquency level (β = 0.12, p < .05) and concentrated disadvantage in 2000 (β = 0.28, p < .05) and exposure to crime at Wave 1 (β = −0.37, p < .05) were associated with the slope of delinquency (though exposure to crime was in the opposite of the expected direction). However, none of these harshness and unpredictability indicators (i.e. victimization, concentrated disadvantage, exposure to crime, unmet material needs, and poverty) was significantly related to pubertal timing at Wave 2.

Finally, we use the formulas discussed above to estimate the duration of the effect of earlier pubertal development on delinquency. Using this equation, predicted log delinquency rate can be identified for person i at time t with a single covariate X:

| 6 |

In this equation, the effect of X on Ŷ* will be 0 if:

| 7 |

We can solve for the time t when X, pubertal timing at Wave 1, will have no effect on , log delinquency rate, and plug in values from the unstandardized estimates of total effect from this model.

| 8 |

This formula indicates that pubertal timing at Wave 1 will have no effect on log delinquency rate 3.48 years after time 0 in the growth curve. Because time 0 in this growth curve is Wave 2, and the mean respondent age at Wave 2 is 12.62, we estimate that the effect of pubertal timing on delinquent behavior will dissipate around sixteen years of age.

Sensitivity Analyses

Readers may reasonably argue that the above model is not a fair test of LH theory because it does not assess harshness and unpredictability early enough. To address this concern, we estimated an additional model (shown as a diagram in Figure 5) that includes measures of harshness and unpredictability both contemporaneously and before Wave 1 (using retrospective report). We have intentionally biased this model in favor of LH theory by 1) using a latent omnibus indicator of harshness and unpredictability (latent variables tend to covary more than manifest variables because they account for measurement error, see Lorenz et al., 1995), 2) regressing pubertal timing at Wave 1 on the latent harshness and unpredictability variable (in contrast to the principle model that required social factors to predict pubertal timing at Wave 2 after accounting for stability in pubertal timing from Wave 1), and 3) using indicators of harshness and unpredictability that covary with pubertal timing. Another model was estimated using pubertal timing at Wave 2; however, we present the model using pubertal timing at Wave 1, which was more favorable to LH theory.

Figure 5.

Further Test of Life History Predictions: Earlier Predictors

The latent harshness and unpredictability construct was estimated using several items. At Wave 7 (2016), respondents reported on childhood trauma “before the age of 10” using the sexual abuse subscale from the childhood trauma questionnaire (Bernstein et al., 1994). Respondents also reported on their exposure to violence prior to age 10 using a 6-item scale, e.g. “there was a lot of violence in my neighborhood,” “there were a lot of fights at my school” (1 = yes, 0 = no), and on the instability in their environment prior to age 10 using a 5-item scale, e.g. “did your parents separate or divorce?” “would you say the number of adults in your home shifted?” (1 = yes, 0 = no). Finally, the respondents reported on unmet material needs prior to age 10. Finally, primary caregivers reported on whether their child had ever engaged in the 25 behaviors in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV conduct disorder subscale (Segal, 2010). Factor loading for this variable are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Measurement Portion for Further Test

Results from this model are shown in Table 3. In this model, pubertal timing was regressed on the latent harshness and unpredictability with no other predictors—providing a substantial amount of variance for harshness and unpredictability to associate with. Residuals for deviant peers, harsh parenting, and pubertal timing were freed to covary. The delinquency growth factors were regressed on all predictors. In this model, the harshness and unpredictability variable predicts initial delinquency (β = 0.28, p < 0.05), puberty at Wave 1 (β = 0.15, p < 0.05), deviant peers at Wave 2 (β = 0.20, p < 0.05), and harsh parenting at Wave 2 (β = 0.19, p < 0.05). Thus in this model, pubertal timing is significantly associated with harshness and unpredictability. However, pubertal timing, contrary to LH theory, does not significantly mediate the association between instability and criminal behavior (initial criminal behavior: β = 0.022, p > 0.05; criminal behavior slope: β = −.078, p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Path Coefficients from Further Test of Life History Predictions: Earlier Predictors

| Delinquency Intercept |

Delinquency Slope |

Puberty, Wave 1 |

Deviant Peers, Wave 2 |

Harsh Parenting, Wave 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puberty, w1 | 0.15 | −0.52 ** | 0.14 * | 0.11 * | |

| Deviant Peers, w1 | 0.01 | −0.41 * | 0.26 *** | −0.11 * | |

| Deviant Peers, w2 | 0.32 *** | −0.01 | |||

| Harsh Parenting, w1 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.39 *** | |

| Harsh Parenting, w2 | 0.20 * | −0.14 | |||

| Harshness and Unpredictability, w1 | 0.28 * | 0.08 | 0.15 * | 0.20 * | 0.19 * |

| PC Education, w1 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.19 *** | −0.03 | −0.09 |

| Delinquency, w1 | 0.11 * | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Age, w1 | −0.11 | 0.30 * | 0.31 *** | 0.13 * | 0.03 |

Note: N = 480; standardized results shown; dependent variables shown in first row, predictor variables shown in first column

p<.06

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

While LH and CR models suggest opposite causal directions between social forces and pubertal timing—i.e. the CR model argues that people respond to girls who develop faster in ways that differentially increase their likelihood to engage in crimes, while LH theory argues that earlier pubertal timing is a visible part of a larger suite of developmental processes including psychological structures that favor criminal behavior that occur in response to social circumstances—these models could incompletely capture the mechanisms underlying the link between puberty and crime. It is possible that both processes are operating simultaneously. That is, harshness and unpredictability in childhood could cause earlier pubertal timing and all attendant psychological schemas, while this earlier timing also frames how others respond to these girls.

We address this hypothesis by estimating a model including a latent factor representing this psychological development. Because Belsky et al. (1991) argue that mistrustful internal working models of relationships and an opportunistic interpersonal orientation are characteristic of a “fast” developing individual, we estimated a latent variable at Wave 1 using instruments representing a hostile view of relationships (also used by Simons et al., 2014) and preference for immediate gratification (same as used as a control above; n.b. we use only the first 12 items of the hostile view scale used by Simons et al, 2014 because the other 6 items were not available at Wave 1). This psychological development factor, as well as deviant peers and harsh parenting at Wave 2, was regressed on pubertal timing, deviant peers, and harsh parenting at Wave 1. Alternate models using psychological development at Wave 2, removing deviant peers and harsh parenting at Wave 2, and covarying deviant peers and harsh parenting with psychological development at Wave 1 rather than regressing did not produce model more favorable to the LH model.

The results from this model are shown in Figure 7. In this model, psychological development is unrelated to pubertal timing (p > .05). Psychological development is however significantly associated with both deviant peers and harsh parenting at Wave 1. Because pubertal timing is not significantly associated with psychological development, it is unsurprising that the indirect path from harshness and unpredictability to psychological development is not significant (β = .022, p > .05). The indirect path running through harsh parenting is, however, significant (β = .091, p < .05). Additionally, psychological development does not predict deviant peer affiliation or harsh parenting at Wave 2; whereas, pubertal timing continues to significantly predict both after controlling for psychological schemas.

Figure 7.

Further Test of Life History Predictions: Incorporating Psychological Development

Discussion and Conclusion

The goal of this study was to answer two questions: 1) what is the mechanism whereby pubertal timing affects delinquent behavior, and 2) how long does the effect last? The CR and LH hypotheses present conflicting explanations for the link between earlier pubertal timing and delinquent behavior. The CR model suggests that girls who develop earlier will be exposed to more hostile parenting and will have more delinquent peers. According to this hypothesis, these social relationships will mediate the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquent behavior. Alternatively, LH theory suggests that girls will develop faster in response to more harsh and unpredictable environments. Hostile parenting and delinquent peers are cues for harsh environmental conditions and thus cause precocious pubertal development.

We found an association between pubertal timing at Wave 1 and initial delinquency that is extremely close to the correlation value of 0.241 Dimler and Natsuaki (2015, p. 165) found for studies using the PDS. However, in our analysis, pubertal timing at Wave 1 was negatively associated with the slope of delinquency. This negative value likely represents some regression toward the mean. That is, girls who have developed faster tend to engage in more initial delinquent behaviors and therefore have more room to engage in fewer behaviors later than those who developed more slowly and never engaged in many behaviors in the first place. However, this large effect size likely also indicates dissipation of effect. Thus, the initial positive effect of pubertal timing on delinquent behavior is attenuated over time. This dissipation of effect mirrors previous findings that cross-section evaluation of this association is stronger than longitudinal evaluation. Thus, these findings are consonant with Dimler and Natsuaki’s (2015) finding that contemporaneous associations between pubertal timing and externalizing behaviors are significantly stronger than longitudinal associations.

Results related to the first question above seem to indicate that the CR model better explains the relationship. Both harsh parenting and peer group deviance at Wave 2 were significantly associated with pubertal timing at Wave 1. Deviant peers and harsh parenting, in turn were both significantly associated with the latent factor representing the intercept of delinquent behavior trajectories. Thus, this model supports the CR propositions that precocious pubertal timing changes girls’ social relationships so that they are exposed to more antisocial influences. Within the CR perspective, the peer effects seem stronger than parenting effects. This model received mixed support only because the parenting pathway indirect effect was marginally significant. All other predictions from this model are borne out in the current study.

This analysis provided no evidence in support of the LH model. This model predicts that girls will non-consciously respond to harsh environmental cues by accelerating somatic development as part of a “fast” LH strategy. This model predicts that people with a “fast” LH strategy will develop more present orientation and hostility to others which will cause an individual to engage in more delinquent behaviors (Dunkel, et al., 2013). Pubertal timing was not significantly associated with either deviant peer group or harsh parenting cross-sectionally at either Waves 1 or 2. Pubertal timing at Wave 2 was not related to either of these constructs measured at Wave 1, and pubertal timing at Wave 2 was not associated with either latent growth factor in this model. Similarly, other potential indicators of environmental harshness and unpredictability were not significantly associated with pubertal timing. The supplemental analyses did show evidence that early childhood adversity was associated with earlier pubertal timing. This is not surprising given that there is a substantial body of evidence suggesting that these factors are associated (Ellis, 2004). However, even in the model which is intentionally biased toward LH theory, pubertal timing does not mediate the relationship between early adversity and criminal behavior. Similarly, in the second supplemental model, pubertal timing was not associated with psychological development, although the indirect path from harshness and unpredictability to psychological development through harsh parenting was significant. Thus, it appears that any effect that childhood harshness and unpredictability is having on psychological development is operating through social rather than developmental processes in this model. Pubertal timing continued to have a direct effect on deviant peer affiliation and harsh parenting at Wave 2 after controlling for psychological schemas; whereas, psychological development had no significant association with deviant peers or harsh parenting. This model does not support the argument that other individuals are interacting with girls who reach puberty in criminogenic way as a result of these girls’ psychological developments. Rather, these social reactions to pubertal timing are robust to the girls’ psychological schemas.

Finally, it appears that on average the effect of pubertal timing on delinquency dissipates around age 16. All girls would be expected to have completed the most visible stages of pubertal development by this age, and therefore differences in rates of somatic development would no longer be apparent. By this point in development other contextual and personal factors seem to have overwhelmed the social dynamics of early puberty.

This study is part of a larger movement in criminology to address bio-environmental interactions. Evidence presented here emphasizes the importance of recognizing the contextual factors driving the apparent relationships between biology and behavior. Our argument is similar to that made by Adkins and Vaisey (2009). They point out that a genetic predisposition to tan easily would not matter for a person never exposed to the sun or in a society that does not value tan skin. Similarly, the phenotypic indicator, pubertal timing, under analysis here only matters because of the contextual social arrangement. In a society where adult roles are assigned at an earlier age, girls who develop earlier may not act out from a sense of age-role mismatch (Moffitt, 1993). Similarly, in a society without cultural value tied to girls’ sexual innocence, parents may not engage in harsh and restrictive parenting in an ineffective effort to control their daughter’s behavior.

This research helps clarify who should be targeted by interventions and how those interventions should be structured. Girls who are presenting signs of more rapid pubertal development appear to be an important subpopulation to target. Interventions should focus on reducing hostility in parent-child relationships and aiding these girls and young women to build more prosocial peer groups.

This research is not without limitations. One potential limitation of the current study is that the mean age of girls at Wave 1 is 10.57 years. Some respondents may have already begun to develop significantly by this point. We have limited information about childhood environment prior to Wave 1. Though the supplemental analysis model attempts to address this concern, it is possible that a study with measures of harshness and unpredictability in infancy and early childhood may have found more support for LH theory as a model of criminal and delinquent behavior. However, several studies have suggested that retrospective and prospective reports of childhood maltreatment are often similarly effective as predictors (e.g. Scott, McLaughlin, Smith, & Ellis, 2012). Future research could address the limitations of the current study by using a sample that includes earlier measurements of parenting and peer behavior and earlier evaluation of pubertal development.

We use an all African American sample. Though it may be possible that girls from other racial groups may show a different pattern of results, we have no theoretical reason that the mechanisms investigated in this study would not operate similarly for other racial groups. Previous research has found differences in pubertal timing by racial group; however, this effect was largely attenuated by socioeconomic indicators included in our model (Obeidallah et al., 2000). Additionally, we find an association between puberty and delinquency that is similar in magnitude to that found in meta-analysis, suggesting that our population is not unique. It is certainly the case, however, that our findings need to be replicated with other ethnic/racial groups. Another potential direction of research would be to identify moderators of the effect of pubertal timing on delinquent behavior. That is, to address for whom pubertal timing matters. Work by Ge, et al. (2006) among others suggests that this line of research may be fruitful. Future research could also clarify how pubertal timing operates for boys’ delinquency. As discussed above, it seems likely that any mechanism linking puberty to boys’ and young men’s offending would be substantially different from those explored here.

The current study contributes to the literature on juvenile delinquency by testing two competing models linking pubertal timing to delinquency. In our sample, we are able to provide firm support for the CR model while finding no support for LH theory as an explanation for delinquency among girls. We are able to estimate both the magnitude and duration of the effect of pubertal timing on delinquency. Finally, we are able to address concerns raised by many feminist criminologists that theories and research must be substantially adapted to address the particularities of female offending. Because experiences of pubertal development are profoundly different for boys and girls, this sensitive period is likely in need of further exploration.

Figure 1.

Proposed Context of Risk Model

Figure 2.

Proposed Life History Model

Table 2.

Path Coefficients from SEM Model

| Delinquency Intercept |

Delinquency Slope |

Puberty, Wave 2 |

Deviant Peers, Wave 2 |

Harsh Parenting, Wave 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puberty, w1 | 0.29† | −0.68 * | 0.64 *** | 0.14 * | 0.14 * |

| Puberty, w2 | −0.21 | 0.23 | |||

| Deviant Peers, w1 | 0.40 *** | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.26 *** | −0.10 |

| Deviant Peers, w2 | −0.08 | −0.29 | |||

| Harsh Parenting, w1 | 0.22 ** | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.42 *** |

| Harsh Parenting, w2 | 0.06 | 0.02 | |||

| Victimization, w1 | 0.12 * | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Concentrated Disadvantage, 2000 | −0.01 | 0.28 * | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| Exposure to Crime, w1 | 0.11 | −0.37 * | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Unmet Material Needs, w1 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Poverty, w1 | 0.10 | −0.35 | −0.10 | −0.12 | 0.04 |

| PC Education, w1 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.08 |

| Delinquency, w1 | 0.12 * | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Age, w1 | −0.13 | 0.34 * | 0.06 | 0.13 * | 0.03 |

| Low Self-Control, w1 | 0.17 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| PC Crime, w1 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

Note: N = 480; standardized results shown; dependent variables shown in first row, predictor variables shown in first column

p<.06

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (HL118045), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD080749), the National Institute on Aging (R01AG055393), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21DA034457), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH62699, R01MH62666). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Eric T. Klopack, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia, 355 S. Jackson St., Athens, GA 30602, 706-542-2421.

Ronald L. Simons, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia, 355 S. Jackson St., Athens, GA 30602, 706-424-2626, rsimons@uga.edu

Leslie Gordon Simons, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia, 355 S. Jackson St., Athens, GA 30602, 706-542-2421, lgsimons@uga.edu.

References

- Adkins DE, & Vaisey S (2009). Toward a unified stratification theory: Structure, genome, and status across human societies. Sociological Theory, 27(2), pp. 99–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01339.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akers RL (1998). Social learning and social structure: A general theory of crime and deviance Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Ruttle PL, Boyce WT, Armstrong JM, & Essex MJ (2015). Early adversity, elevated stress physiology, accelerated sexual maturation, and poor health in females. Developmental Psychology, 51(6), pp. 816–822. doi: 10.1037/dev0000017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Schlomer GL, & Ellis BJ (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), pp. 662–673. doi: 10.1037/a0024454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, & Draper P (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62(4), pp. 647–670. doi:0.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, … Ruggiero J (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(8), 1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), pp. 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy L, & Agnew R (1997). Gender and crime: A general strain theory perspective. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 34(3), pp. 275–306. doi: 10.1177/0022427897034003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, & Miller J (2012). Precocious role-entry as a mediating factor in women’s methamphetamine use: Implications for life course and pathways research. Criminology, 50(1), pp. 187–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00248.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Lynam D, Moffitt TE, & Silva PA (1993). Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), pp. 19–30. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charnov EL (1993). Life history invariants: Some explorations of symmetry in evolutionary ecology Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm JS (1993). Death, hope, and sex: Life-history theory and the development of reproductive strategies. Current Anthropology, 34(1), pp. 1–24. doi: 10.1086/204131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, & Werre D (2008). A longitudinal study of the effects of uncertainty on reproductive behaviors. Human Nature, 19(4), pp. 426–452. doi: 10.1007/s12110-008-9052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M (2009). Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. The Behavioral And Brain Sciences, 32(1), pp. 1–67. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimler LM, & Natsuaki MN (2015). The effects of pubertal timing on externalizing behaviors in adolescence and early adulthood: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 45, pp. 160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel CS, Mathes E, & Beaver KM (2013). Life history theory and the general theory of crime: Life expectancy effects on low self-control and criminal intent. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 7(1), pp. 12–23. doi: 10.1037/h0099177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ (2004). Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), pp. 920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Del Giudice M, Dishion TJ, Figueredo AJ, Gray P, Griskevicius V, … Wilson DS (2012). The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), pp. 598–623. doi: 10.1037/a0026220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, & Essex MJ (2007). Family environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: A longitudinal test of a life history model. Child Development, 78(6), pp. 1799–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Figueredo AJ, Brumbach BH, & Schlomer GL (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20(2), pp. 204–268. doi: 10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, McFadyen-Ketchum S, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, & Bates JE (1999). Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), pp. 387–401. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA, Boyce WT, Deardorff J, & Essex MJ (2011). Quality of early family relationships and the timing and tempo of puberty: Effects depend on biological sensitivity to context. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), pp. 85–99. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB, & Haynie DL (2002). Pubertal development, social factors, and delinquency among adolescent boys. Criminology, 40(4), pp. 967–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00979.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo AJ, Vásquez G, Brumbach BH, Schneider SMR, Sefcek JA, Tal IR, … Jacobs WJ (2006). Consilience and life history theory: From genes to brain to reproductive strategy. Developmental Review, 26, pp. 243–275. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo AJ, Vásquez G, Brumbach BH, Sefcek JA, Kirsner BR, & Jacobs WJ (2005). The K-factor: Individual differences in life history strategy. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(8), pp. 1349–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, & Simons RL (2006). Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 35(4), pp. 528–537. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9046-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, & Murry VM (2002). Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology, 38(1), pp. 42–54. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XJ, Brody GH, Conger RD, & Simons RL (2006). Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(4), pp. 531–540. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9046-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL (2003). Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquency involvement. Social Forces, 82(1), pp. 355–397. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, & Piquero AR (2006). Pubertal development and physical victimization in adolescence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 43(1), pp. 3–35. doi: 10.1177/0022427805280069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), pp. 424–453. doi: 10.1037//1082-989x.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DB (2012). The role of early pubertal development in the relationship between general strain and juvenile crime. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 10(3), pp. 292–310. doi: 10.1177/1541204011427715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM (2009). Gendered responses to serious strain: The argument for a general strain theory of deviance. Justice Quarterly, 26(3), pp. 410–444. doi: 10.1080/07418820802427866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, & Wilcox LE (1979). Self-control in children: Development of a rating-scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(6), pp. 1020–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.6.1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.) New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Cho J, Simons LG, Allen KA, Beach SRH, Simons RL, & Gibbons FX (2014). Pubertal timing and sexual risk behaviors among rural African American male youth: Testing a model based on Life History Theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0410-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger DJ, Aiyer SM, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2014). Local scarcity of adult men predicts youth assault rates. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1), pp. 119–125. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger DJ, Reischl T, & Zimmerman MA (2008). Time perspective as a mechanism for functional developmental adaptation. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2(1), pp. 1–22. doi: 10.1037/h0099336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Simons RL, & Whitbeck LB (1995). The effects of unequal covariances and reliabilities on contemporaneous inference: The case of hostility and marital happiness. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(4), pp. 1049–1064. doi: 10.2307/353422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, & Elder GH Jr. (2006). The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(2), pp. 111–125. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J (2014a). Beyond pubertal timing: New directions for studying individual differences in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), pp. 215–219. doi: 10.1177/0963721414530144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J (2014b). Why puberty matters for psychopathology. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), pp. 218–222. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), pp. 674–701. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Elliott MN, Davies S, Tortolero SR, Cuccaro P, & Schuster MA (2014). Early puberty, negative peer influence, and problem behaviors in adolescent girls. Pediatrics, 133(1), pp. 7–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0628d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Elliott MN, Gilliland MJ, Grunbaum JA, Tortolero SR, Cuccaro P, & Schuster MA (2008). Positive parenting and early puberty in girls: Protective effects against aggressive behavior. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(8), pp. 781–786. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.8.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, McGee TR, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, & Williams GM (2009). The impact of puberty on aggression/delinquency: Adolescence to young adulthood. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 42(3), pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidallah DA, Brennan RT, Brooks-Gunn J, & Earls F (2004). Links between pubertal timing and neighborhood contexts: Implications for girls’ violent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(12), pp. 1460–1468. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142667.52062.le [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeidallah DA, Brennan RT, Brooks-Gunn J, Kindlon D, & Earls F (2000). Socioeconomic status, race, and girls’ pubertal maturation: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Journal of research on adolescence, 10(4), pp. 443–464. doi: 10.1207/sjra1004_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, & Boxer A (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(2), pp. 117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, & Earls F (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, McLaughlin KA, Smith DAR, & Ellis PM (2012). Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), 469–475. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DL (2010). Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV). In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher PW, Cohen P, Placentini J, Davies M, … Regier D (1993). The diagnostic interview schedule for children-revised version (DISC-R): I. Preparation, field testing, interrater reliability, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(3), pp. 643–650. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RG, Blyth DA, Van Cleave EF, & Bush DM (1979). Entry into early adolescence: The impact of school structure, puberty, and early dating on self-esteem. American Sociological Review, 44(6), pp. 948–967. doi: 10.2307/2094719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Sutton TE, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, & Murry VM (2016). Mechanisms that link parenting practices to adolescents’ risky sexual behavior: A test of six competing theories. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(2), pp. 255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0409-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]