Abstract

Background.

Transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people have gained visibility in public discourse leading to greater awareness, understanding, and social change. However, progress made in policies to combat stigma and improve public accommodation and healthcare for this minority population have been targeted for reversal, particularly since the 2016 presidential election. This study investigated the impact of changes in sociopolitical climate on perceptions of vulnerability and resilience among participants of a longitudinal study of transgender identity development.

Methods.

We randomly selected 19 TGNC participants in New York, San Francisco, and Atlanta, and conducted in-depth interviews about their perceptions of societal progress and setbacks, community engagement, and desired future change. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 68; half (47.4%) identified their gender identity along the feminine spectrum (male assigned at birth) and the other half (52.6%) along the masculine spectrum (female assigned at birth).

Results.

Content analysis revealed that greater media visibility was perceived as both positive (improved awareness of needs) and negative (increased vulnerability to stigma). Setbacks included concerns about personal safety, the safety of others (particularly those with multiple stigmatized identities), healthcare access, and policies regarding public accommodation and nondiscrimination protections. Coping strategies included social support, activism and resistance, and an enduring sense of optimism about the future.

Conclusion.

TGNC Americans, in spite of a long history of adversity, are resilient. Participants demonstrated unwavering motivation to create a better future for themselves, other minorities, and society. Research is needed to quantify the impact of policy changes on health and wellbeing, and identify moderators of resilience amenable to intervention.

Keywords: Transgender, sociopolitical climate, public policy, health, resilience

INTRODUCTION

Since the 2016 presidential election season, during which the role of the government in protecting the rights of minority populations was debated, health authorities have expressed concern about differential effects of changes in public discourse and policy environment on the health of various subpopulations, particularly stigmatized, marginalized groups (1, 2). Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (TGNC) people are individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth (3). They are an especially vulnerable population facing discrimination on sociocultural, institutional, and interpersonal levels, experiencing prejudice events as well as chronic stress. Socioculturally, TGNC people are stigmatized for their nonconformity in gender identity and gender expression. The dominant sociocultural script expects males to identify as men and be masculine in appearance, behavior, and personality, and females to identify as women and be feminine; deviation of this binary norm is marked as “other” while power and privilege are bestowed on those that conform (4). On an institutional level, TGNC people face the challenge of having to navigate systems build on a binary understanding of sex/gender and have been negatively affected by the policies that reinforce the binary norm. For example, the ability to change one’s gender marker on identity documents has historically prioritized genital anatomy over gender identification, preventing TGNC individuals who did not have genital surgery from obtaining identity documents reflecting their gender identity and expression (5). Anti-discrimination policies often exclude TGNC people, eluding them protections against discrimination in education, employment, housing, and public accommodation (e.g., access to public bathrooms) (6, 7). TGNC people’s ability to serve openly in the military has been challenged based on potential disruption of unit cohesion or effectiveness and costs of gender-affirming medical interventions (8, 9, 10). TGNC people also have faced barriers in accessing gender-affirming healthcare due to lack of health insurance in general, specific exclusions in coverage of gender-affirming medical interventions, and the lack of trained healthcare providers (11, 12). On an interpersonal level, TGNC people report high rates of verbal, physical, and sexual harassment and abuse because of their gender identity or expression, (13, 14), and encounter prejudice, ambivalence, and refusal to treat in their interactions with healthcare providers (15).

The minority stress model postulates that these experiences of discrimination, along with anticipated rejection, concealment of identity, and internalized negative attitudes toward gender nonconformity, affect health negatively, whereas coping and social support may buffer the negative impact of minority stress on health (16, 17). TGNC Americans experience disparities in general physical health, mental health, and myocardial infarction (18, 19), and among subgroups, high rates of HIV, depression, anxiety, and substance use have been found (13, 20, 21). The lack of anti-discrimination protections and other supportive policies has been associated with adverse physical symptoms and suicide attempts (22, 23). Gender-related interpersonal discrimination and anticipated rejection predicted psychological distress among a large, national sample of TGNC people (13), whereas social support and facilitative coping have been shown to be protective (13, 24, 25, 26).

Resilience has been defined as a set of coping skills and strategies that help individuals and communities navigate adversity (27). Scholars have studied the resilience that TGNC people and communities develop to navigate anti-trans bias and buffer the negative impact of minority stress on health (25, 26, 28, 29, 30). These studies suggest that key aspects of TGNC resilience processes include being able to define one’s own gender and being able to develop pride in TGNC identity, and for TGNC people of color, also pride in their identity as a person of color (28, 31). Other important TGNC resilience processes are cultivating a sense of hope or optimisim to buffer anti-trans bias and increase self-worth, and, particularly for TGNC people of color, drawing from spiritual beliefs to counter discrimination (30, 31). Engaging in community activism, helping others, and serving as a mentor, have also been suggested as key components of TGNC resilience (30, 31). However, it is important to keep in mind that research on the impact of minority stress on the health of TGNC people to date has been cross-sectional, limiting our ability to understand the mechanisms involved in minority stress processes, coping and social support, and the development of resilience.

Project AFFIRM aims to fill this gap by taking a longitudinal approach to investigate the development of identity and resilience in the face of gender-related stigma and minority stress. More specifically, Project AFFIRM aims to understand how TGNC individuals cope with challenges they face throughout their lives and identify modifiable factors of resilience to inform interventions to promote their health and well-being (R01-HD79603, Walter Bockting, PI). During annual, quantitative interviews with TGNC participants in New York, San Francisco, and Atlanta (N = 330), we noticed an impact of recent changes in the national sociopolitical climate on participants’ responses. After a period of accelerating visibility of TGNC people, increased awareness of their needs, and improved access to gender-affirming healthcare and public accommodation, such progress seemed to come to a halt, and hard-fought rights were under threat (32, 33, 34, 35). This prompted us to conduct qualitative, in-depth interviews with randomly selected participants to explore the impact of recent changes in sociopolitical climate on their perceptions of vulnerability and resilience. More specifically, we were interested in learning about their experiences of societal progress and setbacks, related fears and concerns, coping and adaptation, as well as their hopes and wishes for social change in the near future. Our findings shed light on how TGNC participants in Project AFFIRM experience and adapt to minority stress related to sudden changes in the current policy environment, informing the work of clinicians and policymakers to promote TGNC people’s health and well-being.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Project AFFIRM, including the qualitative study presented here, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute / Columbia Psychiatry. For the larger, quantitative study, participants who self-identified as TGNC (N = 330) were recruited through purposive, venue-based sampling across a variety of online and offline settings identified through ethnography in three major US metropolitan areas (36). Venues included public spaces and commercial establishments, community events and groups, social media, transgender-specific healthcare clinics, and word of mouth. Clinics excluded those primarily focused on mental health, as this was the main outcome of the larger study on the development of identity and resilience across the lifespan. Once recruited and screened, we used quota sampling to select and enroll participants stratified by age group (16–20, 21–24, 25–39, 40–59, 60 and older), gender identity (transfeminine, transmasculine, nonbinary), and study site (New York City, San Francisco, or Atlanta), maximizing diversity in ethnicity/race. In response to changes observed in participants’ responses during the annual quantitative assessment of this larger cohort, we randomly selected 6–7 participants per study site to complete in-person, qualitative interviews in June and July of 2017. A total of 19 participants across the three study sites were invited, and all of them completed the interview. As projected by Guest, Bunce, and Johnson (37) the sample size of n = 19 was sufficient to reach data saturation.

We chose random selection because we were interested in getting a sense of how the overall sample of the larger study was affected by the recent changes in sociopolitical climate (Table 1). Mean age of participants (n = 19) was 36.3 (SD = 16.2, range 18 – 68). About half (47.4%) identified as woman (n = 2), trans woman (n = 6), or genderqueer / nonbinary (n = 1) while assigned male at birth, and the other half (52.6%) identified as man (n = 2), trans man (n = 4), genderqueer / nonbinary (n = 4) while assigned female at birth. About a third (31.6%, n = 6) were White, 31.6% (n = 6) African American, 26.3% (n = 5) Latino, and 10.5% (n = 2) Asian / Pacific Islander. The majority (73.7%, n = 14) completed at least some college; the remainder (26.3%, n = 5) completed high-school (n = 3) or less (n = 2). About two-thirds (68.4%) were employed; the remainder (31.6%, n = 6) were retired (n = 2), unemployed (n = 2), a student (n = 1), or disabled (n = 1). The median annual income was between $24,000 and $35,999. Most participants (73.7%, n = 14) were receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy and 36.8% (n = 7) had some kind of gender-affirming surgery

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of interview participants (N = 19)

| Participant | Age | Sex Assigned at Birth | Gender Identity | Race | Hispanic | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York | ||||||

| 1 | 54 | Male | T ransgender woman / MTF | Black, African American | No | Undergraduate degree |

| 2 | 53 | Male | T ransgender woman / MTF | Latina | Yes | Some college |

| 3 | 23 | Female | Transgender man / FTM | White | Yes | Some college |

| 4 | 48 | Female | Transgender man / FTM | White | No | Some college |

| 5 | 33 | Female | Transgender man / FTM, Genderqueer, Transmasculine | White | No | Graduate degree |

| 6 | 19 | Male | T ransgender woman / MTF, Female | Black, African American | No | High school |

| San Francisco | ||||||

| 7 | 19 | Female | Genderqueer | Asian | No | High school |

| 8 | 44 | Female | Transgender man / FTM | White | No | Undergraduate degree |

| 9 | 65 | Male | T ransgender woman / MTF | Mexicana | Yes | Less than high school |

| 10 | 27 | Female | Transgender woman, MTF, Woman | White | No | Undergraduate degree |

| 11 | 22 | Male | Another gender (non-binary transgender) | Asian, White | No | Some college |

| 12 | 30 | Female | Transgender man/FTM, Man | White | No | Some college |

| 13 | 29 | Female | Transgender man, FTM | Black, African American | Yes | High school |

| Atlanta | ||||||

| 14 | 31 | Male | T ransgender woman / MTF | Black, African American | No | Unknown |

| 15 | 26 | Female | Transgender man / FTM | Black, African American | No | Some college |

| 16 | 60 | Male | Woman | White | Yes | Some college |

| 17 | 28 | Female | Genderqueer, Non-binary, GNC | Black, African American | No | Some college |

| 18 | 27 | Female | Genderqueer, Agender, Gender fluid | Black, African American | No | Graduate degree |

| 19 | 69 | Male | Transgender woman / MTF | White | No | Some college |

Instrument

The first, second, and fifth author developed an interview guide (Appendix A) and modified earlier drafts according to additional feedback from the third and fourth authors. First, participants were asked to describe moments of progress in society that had a positive impact on the lives of TGNC people. Second, we asked them whether they shared concerns voiced by participants of Project AFFIRM about the pendulum swinging back, potentially losing some of the gains in transgender rights made in recent years. Third, we asked participants what policy changes they would like to see in the near future. Finally, we asked them if the sociopolitical changes discussed during the interview led them to become more active in their community.

Analysis

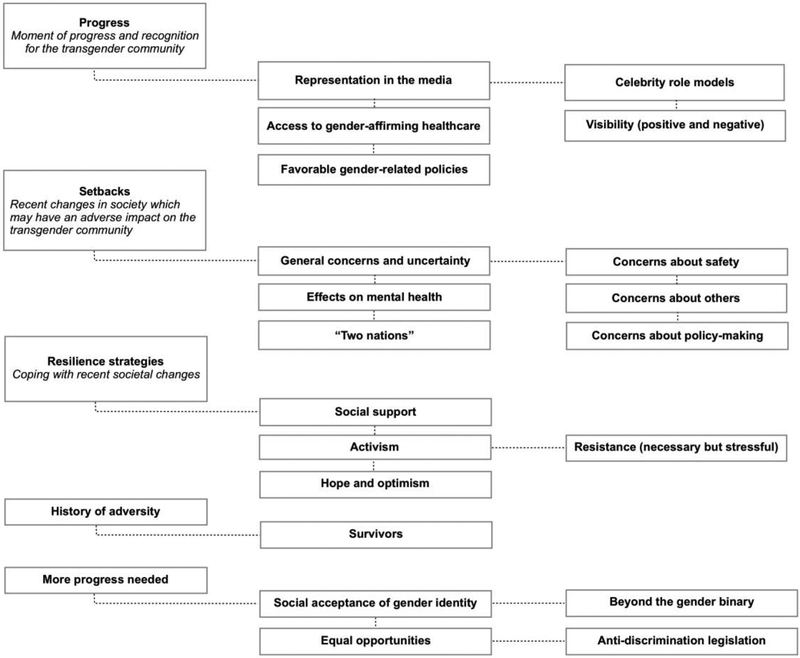

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription service. A conventional content analysis (38) was performed by the second author using Dedoose, an online software solution in which a code-book was created. Initial codes emerged directly from the text. Codes subsequently were sorted into categories based on how they were linked in participants’ narratives as well as upon reflection by the second and first author. Codes were then organized and grouped into meaningful clusters. A tree diagram was developed to organize categories into a hierarchical structure (Figure 1), and representative quotes were selected to illustrate each finding. To determine inter-rater reliability, the fifth author independently coded a randomly selected 47 excerpts into 12 coding categories, resulting in a Kappa of .85.

Figure 1.

Tree Diagram of Coding Categories and Themes

RESULTS

Review of interview transcripts by city (New York, San Francisco, or Atlanta) and gender (transfeminine or transmasculine spectrum) did not indicate any site- or gender-specific results. Therefore, findings are presented for all participants together. Within each section, we present the most commonly reported experiences and concerns first, followed by additional salient findings for our purpose of understanding participants’ reactions to sociopolitical change and the development of resilience.

Progress

Participants acknowledged progress in recent years in terms of visibility of TGNC people in the media. They noticed an increase in representations of TGNC persons in film, television, and social media, and the rise of transgender celebrity role models. Participants considered this a sign of progress and as an opportunity to further social acceptance and transgender rights. Authentic storylines in film and television, particularly those featuring trans-identified actors playing transgender roles, along with real-life testimonials on social media platforms and voices from such celebrities as Laverne Cox and Janet Mock, were perceived as affirming and validating. These storylines, testimonials, and voices were seen as offering a glimpse into the lives of TGNC people for mainstream audiences, expected to facilitate greater understanding of their identities and needs:

They’re the beginning of the representation for trans people, and people are going to see that it’s not so strange. It’s more normal. It’s normalizing the idea of trans identities.

(Black transgender man, 26 years old, living in Atlanta)

I think it’s been great for me. I’m constantly trying to figure out where I fit in. So for me, it’s been really good. Instagram and Tumblr are my two main go to’s for my own exposure to the community. I think the non-binary community is where I belong and feel a part of. I didn’t know that it existed, didn’t have a name for it, until maybe two or three years ago.

(White, genderqueer / non-binary participant, 33 years old, living in New York City)

Participants also mentioned progress in access to gender-affirming healthcare, including better availability of transgender care providers and services, improved access to health insurance, and greater inclusion of gender-affirming medical interventions in insurance benefits. As participants explained:

A key thing in my life has been getting health insurance to cover transgender-related healthcare costs. I personally had wanted to have top surgery when I was like 20, and I’m 44 now, and I just had surgery this year because my health insurance now pays for it.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

More availability of clinics that specifically offer HRT [hormone therapy] services, Planned Parenthood, um, branching out into starting to offer HRT at least at some of their centers. The rise of availability of getting HRT through informed consent rather than through the model where you get a letter through a psychiatrist or psychologist.

(White transgender woman, 27 years old, living in San Francisco)

Finally, participants noted favorable gender-related policy changes, such as greater ease in changing name and gender marker on identity documents like driver’s licenses and passports, and the right to marry regardless of the gender identity of partners:

To be able to change your gender, change your name, marry, do some of those things that five years ago or ten years ago would be, you know, just in somebody’s wildest dreams. A fair amount has been accomplished, that’s great.

(White transgender woman, 69 years old, living in Atlanta)

I think important moments would be when new laws are created. Surgery access is good too, because some people want to fit the gender binary.

(Black transgender man, 29 years old, living in San Francisco)

While talking about increased visibility, most participants also mentioned how, in addition to a sign of progress, visibility may also have played a role in the recent backlash against transgender rights (e.g., the 2016 House Bill 2 in North Carolina, which allowed people to only access gender-segregated facilities in government buildings that correspond to the sex listed on their birth certificate) and make them more vulnerable to being a target of stigma and discrimination:

It’s a two steps forward, one step back problem. I think one of my biggest concerns is that, I don’t want to say this negatively, but the more people are willing to come out, the more people push for this idea that it’s okay {to be trans] and we accept ourselves as people in the trans community, the more people who are against it are going to push back. Like, for me, one of the biggest ones was the law in North Carolina [the “bathroom bill,”, i.e., the Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act].

(White transgender man, 23 years old, living in New York City)

Setbacks

Concerns about the backlash against the progressive changes of recent years made participants feel their rights and safety were under attack. Participants reported worrying about physical safety in public spaces as the current social climate seemed to encourage discrimination, mistreatment, and rejection. They feared for their personal safety and the safety and predicament of other vulnerable populations (e.g., youth, the poor and undocumented):

I’m hearing stories of an increase in hate crimes. With the election of Trump, different extremist groups and individuals are feeling more empowered to verbally harass or assault people.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

It is already scary to go outside and be who you are in a world that says you can’t look the way you do. In our society we see government as someone that should protect you and help support you. It now just feels like the government is keeping you down and telling you that you don’t have rights, you shouldn’t exist, or you shouldn’t be here. How can you possibly feel safe in that?

(White genderqueer / non-binary participant, 33 years old, living in New York City)

One of the first actions of the administration was to directly attack trans youth and education, which was very disturbing. So many trans people are living on the margins, economically, with mental health and other challenges. All of his [Trump’s] policies support corporations instead of people.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

I have no family in New York, so my sister was afraid I was going to be alone. My fear for her was really as an illegal immigrant, she has a family here. She has her husband. She has her daughter. What happens to them, what happens to their daughter if they get deported?

(Latino transgender man, 23 years old, living in New York City, who himself is a U.S. citizen)

Participants shared both general uncertainties about the future and specific fears for ethnic/racial and religious minority populations:

I guess it’s hard to say because I just feel like it’s so, sorry, so unpredictable. I feel like Donald Trump is like a toddler, like he just kind of does whatever he wants to do. I anticipate that there will be more of a pushback against social justice and there will be like this push for traditional family values and gender essentialism.

(Black genderqueer / non-binary participant, 27 years old, living in Atlanta)

Another participant was more specific:

None of the original parameters by which we understand government and civic engagement seem to exist anymore. They are all elastic, and everything seems infinitely changeable, so it’s hard to say what I expect. I think things are going to get worse and more bizarre. I would say that this whole election season and election of Donald Trump was a huge setback. People are overt in their hate of other people. Brown people, Black people, people from the Middle East, gay people, Jews… everybody now is a target.

(White transgender man, 48 years old, living in New York City)

Participants worried that further setbacks could impact their civil rights. Restrictions in access to competent healthcare, appropriate bath- and locker rooms, and changing the gender marker on identity documents could further complicate their lives:

Uh, you know about losing rights, about not being able to change names, change genders, you know to have some freedoms that we’ve realized in the last several years

(White transgender woman, 69 years old, living in Atlanta).

If the Affordable Care Act gets repealed then a lot of people are gonna die. Um, yeah, a lot of people, one way or another.

(White transgender woman, 27 years old, living in San Francisco)

I am worried about the changes they are going to make, like medical stuff to take care of people.

(Latina transgender woman, 65 years old, living in San Francisco)

Participants described how these setbacks had a direct negative impact on their wellbeing, worsening the quality of everyday life. Most participants disclosed feeling increasingly anxious since the election. Ordinary activities, such as shopping, scrolling through social media feeds, and walking down the street, were considered stressful. Participants reported feeling scared and isolated. Depression, suicidality, sleeplessness, and struggle to cope with uncertainties were also reported:

Oh, certainly stressful. And you know living with that kind of stress, like just the presence of it itself, is detrimental to your health. Not to mention, let’s say you needed to go to the doctor for a specific condition, like even just a cold, not just a cold… I mean like you can’t get insurance so then it’s too expensive to go to the doctor. So, it’s like you’ve already got that illness and then you are stressed on top of that.

(Black genderqueer / non-binary participant, 28 years old, living in Atlanta)

I mean, my life is in jeopardy, you know? And then it comes to the point where my depression gets so bad I go… I could take my life.

(Latina transgender woman, 60 years old, living in Atlanta)

I’m too stressed out to sleep. And I think about how under the Trump administration the United States is, like, gonna get worse, it’s gonna, there’s gonna, it’s gonna be more right wing, more fascist than we’ve already been.

(Asian genderqueer / non-binary participant, 22 years old, living in San Francisco)

Finally, participants expressed concern about the existence of ‘two nations,” referring to polarization between the right and the left, and the differences in policies and climate in red versus blue states. Parts of the country, such as New York and California, were seen as seeking to better accommodate and protect TGNC people, whereas other parts of the country were seen as seeking to limit accommodation and implement policies that discriminate on the basis of gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation:

I think we’re really lucky in New York. There’s all these places we can go for care or housing, for example. This doesn’t exist in many other parts of the country and so, I would worry personally if I were living in Oklahoma. I don’t know if I would want to go to a doctor. So, even if I’m healthy now, my worry about how I will be treated in places that are supposed to give me care, will make my health worse.

(White genderqueer / non-binary participant, 33 years old, living in New York City)

I think in some states they’re going to pass the bathroom bills, that legislation, but in other states, we’ll continue [as is]… it’ll be a lot of states’ rights kind of thing, and other states will continue moving towards the future instead of sticking around in the past.

(Black transgender man, 26 years old, living in Atlanta)

Although Georgia is a red state with more restrictive policies (i.e., no state-wide anti-discrimination protections for TGNC people) (39), we did not observe any differences in concern of participants about this across study sites. This may be due to the fact that Atlanta is the only city in Georgia to receive a perfect score on the Human Rights Campaign’s Municipal Equality Index (40), which assess laws, policies, and services related to non-discrimination, creating somewhat of a safe haven for TGNC people in the South.

Resilience strategies

Coping and resilience strategies to deal with setbacks in social acceptance and public accommodation included social support, staying ahead of the curve, activism and resistance, and a sense of optimism about the future. Building and maintaining healthy relationships was seen as a strategy to prevent or overcome estrangement. When negative thoughts occured, close friends, significant others, peer support groups, and mental health professionals helped to put fears in perspective and find effective ways to deal with real and perceived threats. Additional sources of support included family members, colleagues, and roommates. Peer support was perceived as particularly important:

It is very useful to have that [peer support] because that means immediately that you have a group, a tangible group of trans and gender nonconforming people to call on if you need help, even if they are not your closest friends, you have this network. And the [trans social justice organization] have chapters all over the country and even some other places in the world. I think that is one example of a group that could bring about positive change in the country.

(Asian genderqueer / non-binary participant, 19 years old, living in San Francisco)

I probably learned most because I started going to a support group for trans folks, and in the support group, they have a couple people who know a lot of information.

(Black transgender man, 26 years old, living in Atlanta)

In the face of threats to recent advances in access to gender-affirming healthcare, some participants coped by accelerating treatment, obtaining needed procedures while still available:

I’ve had this very visceral feeling that my healthcare was going to go away for trans-related procedures. I know it’s sort of a many step process to undo Obamacare and the trans protections that were related to that, but I definitely felt vulnerable. So I sought steps to have any procedures I needed quickly done before the rights were taken away.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

Others felt confident they would find ways to work around restrictions created by changes in laws and policies:

I educate myself and educate people around me about how to work around the system because, as it is now, they can’t stop you from doing everything. I don’t think they ever will be able to stop you from doing everything. I don’t think they’ll get… they’ll get their way.

(Black transgender man, 26 years old, living in Atlanta)

The impact of engaging in activism was experienced as both positive and negative. Participants saw activism as inherent to their experience of identity. They perceived activism as empowering, and as something they often did not have a specific “choice” about, but rather felt they needed to do to advocate for their own rights as TGNC people and for the rights of their community:

I think inherently as a transwoman you either have the choice to make yourself a disease or you’re an activist, and even if you choose the first you’re still forced to be an activist because your existence is inherently political.

(White transgender woman, 27 years old, living in San Francisco)

Participants described engaging in activism as empowering because it exposed them to a larger community of TGNC people who were strong advocates, which helped them increase their own sense of self-worth. In addition, they were able to develop new and ongoing relationships within the community of TGNC activists and their allys, while learning new information about their legal rights as TGNC people and the importance of trans-affirming legislation. At times, however, activism was also experienced as stressful and overwhelming. As participants learned more about their own needs and the needs of their community within activist movements, they also learned more about the extensive anti-trans stigma that exists in society. This growing awareness was experienced as stressful, as were decisions about how to and when to best invest their energy in activism. Many participants described their experiences of activism as including a roller-coaster ride of emotions, with having some successes, but also experiencing more directly the stress of having setbacks:

I do and I don’t [enage in activism]. Um, mostly because, like, when you’re an activist, you always have this sort of feeling like you are not doing enough and that you should be doing more, you should be, like, putting all your time and thought and energy into being an activist. The problem with that, though, is that, like, you do that, and your mental health is up here and then, later, your mental health is down here, because you’re just feeling, like, so crushed and hopeless and feeling so much despair because there’s a lot to do. I think it’s stressful because you want to see change happen immediately, but a lot of the time, change takes forever. So, activists can be, like, discouraged, under stress.

(Asian genderqueer / non-binary participant, 22 years old, living in San Francisco)

Most participants reporting taking part in rallies, marches, and other forms of direct action in the months preceding the interview. Such demonstrations were a way of voicing dissent and reclaiming their basic right to exist. Although some participants expressed disillusionment with the larger resistance movement (i.e., questioned its effectiveness), many participants saw their own resistance as meaningful:

I have been more empowered to express my anger, to stand up for myself and to say I don’t deserve to be treated like this. So I feel like if that keeps happening and more people are empowered to stand up for themselves, that can affect wider social change.

(Asian genderqueer / non-binary participant, 19 years old, living in San Francisco)

The Women’s March was kind of disillusioning because it was not trans-inclusive in any meaningful capacity. Um, but things like the protests, the mass protests at airports, for maybe a couple of weeks there was a sense that people were going to look out for each other. They were saying they were going to do that, they were going to mobilize more to find ways to protect people and resist the current political stuff happening.

(White transgender woman, 27 years old, living in San Francisco)

Despite feelings of hopelessness, most participants recognized faith in a brighter future is essential. Optimism was considered vital, a source of hope. Most participants believed in the inevitability of progress and the ultimate integrity of humankind:

I want to stay positive; things are going to have to get better, because for every good thing, there’s a step backwards, but for every step backwards, there’s also something that pushes it forward. I feel one of the biggest things we keep seeing is that no matter how many bad things might be pushed our way--politically or people are just negative--people are willing to stand up.

(Latino transgender man, 23 years old, living in New York City)

I’ve always been an optimist in my life. Things may be terrible today for one reason, but recently it wasn’t terrible, and in the future it won’t be terrible.

(Whte transgender woman, 69 years old, living in Atlanta)

History of adversity

Participants described hardship throughout their lives due to stigma and a lack of healthcare access. In light of their long history of adversity, many participants were not necessarily especially worried about recent sociopolitical changes. Rejection, discrimination, and lack of opportunities throughout their lives resulted in a general sense of hopelessness about their lives as a TGNC person and low expectations about the options available to them. As a result, recent setbacks and threats were not entirely unexpected, nor something they had not coped with before. They saw themselves as survivors:

I know I will fight. I will keep doing what I’ve been doing all my life for me, but as far as the larger community, uh, I still am scared to see what’s going to be next and how it’s going to affect us. We’re hoping that we can continue keeping what we have, because it took us hard work and all these years for us to be where we’re at.

(Latina transgender woman, 53 years old, living in New York City)

Need for more progress and specific changes

Participants articulated the need for progress made prior to the 2016 election to continue. This included more progress in social acceptance of gender diversity, the safety and protection of TGNC people, and the promotion of transgender rights:

It is nice to, you know, have more media representation of trans people, but I feel we need more concrete and immediate changes, like now.

(Asian genderqueer / non-binary participant, 22 years old, living in San Francisco)

I’m not sure if I see tons of progress. I see more notoriety or recognition, but I don’t know if I necessarily see a lot of progress. It’s not necessarily moving the conversation forward. There’s still problems, right? We still have Trump, we still have problems in the South, we still have, so no, I don’t have a moment where I can say, “Oh, yeah, now we’re there, this is it.”

(White transgender man, 48 years old, living in New York City)

Participants wanted to see representation of TGNC people in politics, further improvements in access to quality healthcare, federal anti-discrimination legislation, better access to housing, and increased employment opportunities:

There need to be specific trans employment efforts. Things to get folks into a different economic position. Then I think, the second thing… barrier removals for surgery and hormones.

(White genderqueer / non-binary participant, 33 years old, living in New York City)

One participant emphasized the importance of anti-discrimination legislation by relating his own experience as follows:

I was fired from a job when I was 20 for being trans, and that still impacts me as a 44-year old. At that time, I was in Rhode Island where there weren’t civil rights protections for employment. I still have this fear of being fired from a job for being trans, even though it’s 24 years ago, it’s still there. So, I think especially just making sure there are those basic civil rights protections about employment, housing, and access to public services.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

Finally, participants emphasized the need to challenge traditional gender norms and increase understanding and acceptance of genderqueer and non-binary identities. This included the option of choosing a gender marker on identity documents other than male or female:

We’re just winning some court battles about being able to identify as trans, to not have to choose a binary gender, so I mean that’s just a simple one but kind of basic to be able to have our gender acknowledged other than just man or woman.

(White transgender man, 44 years old, living in San Francisco)

Participants who identified in non-binary terms felt that current narratives do not include adequate representation of fluid gender identities beyond the binary of male and female, trans women and trans men. They believed that an in-depth reflection on the construct of gender could ultimately lead to greater societal understanding of gender diversity. Moreover, participants considered objecting to and confronting limiting gender norms more generally as critical step toward greater acceptance and integration of TGNC people in society:

I think broad notions of gender in general but specifically toxic masculinity, because that’s what’s killing Black and Brown trans women. Access to proper medical care and non-discrimination agreement and housing, getting folks off the streets, and drug use and all these things are very important, but I think we need to address people being killed most urgently.

(Black genderqueer / non-binary participant, 27 years old, living in Atlanta)

DISCUSSION

After a period of rapid progress in visibility and public discourse during which transgender issues took center stage as, in the words of former Vice President Joe Biden (41), the “civil rights issue of our time,” a new administration has attempted to reverse some of the Obama-era policies protecting TGNC Americans from discrimination (9, 32). Findings from interviews with Project AFFIRM participants revealed a lived experience of “two steps forward, one step back.” Participants had experienced periods of progress and setbacks before, and, in Dr. Martin Luther King’s words, expected the arc of the moral universe to be long, but bend towards justice (42). Participants acknowledged progress in representation of TGNC people in the media and improved access to gender-affirming healthcare, identity documents, and marriage. Perceived setbacks included an administration that represents the prejudice against TGNC people and other minorities that still exists in American society, insecurity about the future, concern for personal safety, and advancement of discriminatory policies affecting the lives of peers, transgender youth, immigrants, and people of color. Participants recognized the problematic emergence of “two nations,” a country divided in terms of values and support for minority populations. They perceived these changes in sociopolitical climate to negatively impact their mental health, contributing to depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal. These findings from our in-depth qualitative interviews were consistent with concerns about discrimination, personal safety, and mental health reported by sexual minority participants in an online survey conducted by Veldhuis and colleagues (43), indicating that concerns about the negative health effects of the 2016 presidential election may indeed be significant for TGNC Americans (1).

In addition to learning about their vulnerabilities, we were also interested in understanding resilience among our TGNC participants. For instance, cultivating a sense of optimism and hope was important for these participants and reminded them not only of their own self-worth, but also of their hope for a better future beyond the current sociopolitical environment. Support from other TGNC people, family, roommates, friends, coworkers, and mental health professionals, helped them to further develop this hope and optimism. Participants engaged in activism, which was seen as both meaningful and necessary, and increased their hope for the future; however, there were times they felt overwhelmed by the new information they learned about the extensiveness of societal anti-trans stigma, and had to make choices about how and when to engage in activism to manage the associated stress. So, it is important to note that engaging in TGNC activism may be both a key support of resilience and a threat to resilience, as it may expose TGNC people to higher levels of stigma (44). Perhaps most remarkably, participants displayed a sense of enduring optimism, which appeared at least in part related to a long history of overcoming adversity. This latter finding is consistent with the construct of personal hardiness, the ability to shake off setbacks more easily, to persevere, and to sustain faith and belief in goals and intentions (45). In Project AFFIRM, we are testing the moderating effect of social support, activism, and individual agency longitudinally to understand the development of resilience over time. The strong sense of optimism and faith in the future expressed by participants in this qualitative study suggests that we may want to include hope and belief in a larger purpose as forms of resilience (28, 30, 31) as well as driving forces in the lives of TGNC people in both good and bad times (46).

Participants expressed grave concern about the welfare of vulnerable others, including youth, ethnic/racial minorities, the poor, and individuals with multiple minority statuses. This included the intersectionality of being trans and of color, trans and poor, and trans and immigrant. It also included concern for cisgender people with marginalized identities. At times concern for others emerged as even stronger than concern for self, consistent with what was found quantitatively among sexual minority women and gender minorities (43). This finding may be specific to the public’s response to the sociopolitical changes since the 2016 election. It signals the opportunity to strengthen coalitions across vulnerable groups to pursue a broader social justice agenda (47).

This study was limited by its exploratory nature, the exclusion of rural participants (especially given the urban-rural divide observed in the 2016 election) and those not fluent in English, and the reliance on one instead of multiple coders. Results should be interpreted with caution and are not generalizable to the larger population of TGNC Americans. Findings are also limited by the cross-sectional nature of this inquiry during the Summer of 2017. Future research should address these limitations, and examine the impact of policy differences and changes across states and over time.

In conclusion, our findings indicated that TGNC people are negatively affected by the stress related to recent sociopolitical changes, concerned for their own safety and welfare as well as that of other Americans. However, the recent setbacks in policy and discourse also seemed to have strengthened their resolve to continue progress toward a society that better accommodates gender diversity. Healthcare professionals can assist TGNC people in this effort by providing safe spaces for patients to express their concerns and fears about the current sociopolitical environment (1), and intentionally assess their experiences in this regard and how these experiences are influencing their overall health and wellbeing. Taking time to connect with TGNC patients in this way has the potential to improve rapport and open conversations between patient and provider that are important (e.g., about identity, stress, coping, social support, mental health and resilience). In addition, healthcare professionals can use these findings to advocate for better access to quality healthcare for TGNC people, and consider ways that they can take a more active stance against TGNC-discriminatory policies (48, 49). It is not only important for healthcare professionals to urge policymakers to enact anti-discrimination legislation and promote TGNC rights, but also to educate these policymakers on the negative influences minority stress has on TGNC people’s overall wellbeing and health. Then, healthcare professionals will have the opportunity to share stories of how they advocate for transgender rights and make immediate changes in their own healthcare settings to become more trans-affirming, which in turn can help their TGNC patients cultivate hope and optimism for a more just future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the transgender community advisory boards of Project AFFIRM in New York City, San Francisco, and Atlanta for their contributions to the overall implementation of our study. This project was in part supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD79603, first author, PI).

APPENDIX A: INTERVIEW GUIDE

General Introduction

The aim of this interview is to investigate the impact of recent societal changes, both regarding moments of progress as well as setbacks, on the lives of transgender people. In Project [name of project blinded for peer review]’s interviews, we discussed how growing recognition of transgender and gender non-conforming people could change society for the better. While discussing this topic, some participants shared their concerns and fears about potential changes in the near future in regards to transgender rights and policies.

We would like to learn more about these concerns and fears, as well as hopes and wishes for the future, by discussing these topics with you during this interview.

Before we begin, let’s look over the consent form. Please read through it, and then we’ll talk about some important points and any questions you might have.

[Give the participant a few minutes to read through the consent form.]

Ok, thanks for reading through it. Let’s talk about a few important points and then we can go over any questions you may have.

We hope to learn more about the impact of recent societal changes in the lives of transgender people.

Today’s interview will last about one hour. We will audio-record this interview to ensure that we clearly understand what you say. We will then make a transcript of the recorded conversation. These transcripts will not include your real name. All audio files will be destroyed at the completion of the project.

This consent form describes the risks associated with your participation. For instance, at times this interview may focus on events or experiences that are difficult to discuss. As noted on the consent form: You are not required to discuss anything you do not want to discuss, and you can stop the interview at any time. If – during the interview – you would like to take a break for any reason, please let me know.

We also describe how we will work to ensure the confidentiality of the information you provide. As stated on the form: No names or identities will be used in any published reports of the research. Only the research team will have access to the research data.

- Finally, the form explains some additional details, including:

- That you will receive $50 for your participation in this interview;

- Who you can contact if you have additional questions or concerns about this project.

Do you have any questions about the consent form?

[Ask the participant to sign the consent form and take the signed copy. Give the participant a new copy of the consent form to take with him/her]

Do you have any questions before we begin?

Individual Interview (45 minutes)

This interview is meant to be a dialogue. Please feel free to stop me at any time if you have any questions. Also, please note you can choose not to answer any question. Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s begin.

- As you might remember, during the Project [name of project blinded for peer review] interview we discussed how the growing recognition of transgender and gender non-conforming people can change society for the better. Can you think of any moment of progress in society that had a positive impact on the lives of transgender people? (Examples: insurance coverage of transgender care, same-sex marriage, increased visibility and presence of transgender people in the media, positive portraits of transgender people in movies and TV shows, etc.)

- Probes:

- Can you describe this event?

- How did it impact transgender people?

- How did it impact you?

- Do you think it will have a lasting impact?

- Progress and social changes typically don’t evolve in linear fashion, but, like a pendulum swinging back and forth, alternate moments of progress and setbacks. Some Project [name of project blinded for peer review]’s participants, while discussing these moments of recognition, defined by Time Magazine as “the transgender tipping point,” also expressed concerns and fears regarding recent changes in our society that, like the pendulum swinging back, may have a negative impact on the lives of transgender people. Do you worry about potentially losing the gains that have been made in recent years? (Examples: “bathroom bill” in North Carolina and similar legislation proposed in other states, hate crimes toward transgender people, outcome of the United States Presidential Election, etc.)

- What does concern you?

- Why does it concern you?

- What was the first thing you did when you learned about this?

- Who did you talk with?

- What did you talk about?

- What kinds of changes do you anticipate?

- Are there specific policies/personal rights you are concerned about?

- What kind of impact would these changes have on your life, your health, and your well-being?

- What might you be planning to do to manage these changes?

- What are your greatest concerns about how things may change for yourself and your community?

- Where do you turn for support when you feel worried about these changes?

- Do you think anything good may come out of these changes?

What would you like to see as the next change/moment of progress regarding transgender rights and policies?

- Have the events we discussed so far led you to become more active in your community?

- If Yes:

- How have you become more active?

- Do you think of yourself as an activist?

- Are you participating in efforts to resist political changes?

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams DR, & Medlock MM (2017). Health effects of dramatic societal events—ramifications of the recent presidential election. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(23), 2295–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeJonckheere M, Fisher A, & Chang T (2018). How has the presidential election affected young Americans? Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 12(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bockting WO (2014). Transgender identity development In Tolman DL & Diamond L (Eds.), American Psychological Association’s handbook of sexuality and psychology (pp. 739–758). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughto JMW, Reisner SL, & Pachankis JE (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westbrook L, & Schilt K (2014). Doing gender, determining gender: Transgender people, gender panics, and the maintenance of the sex/gender/sexuality system. Gender & Society, 28(1), 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisner SL, Hughto JMW, Dunham EE, Heflin KJ, Begenyi JBG, Coffey- Esquivel J, & Cahill S (2015). Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. The Milbank Quarterly, 93(3), 484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seelman KL (2016). Transgender adults’ access to college bathrooms and housing and the relationship to suicidality. Journal of homosexuality, 63(10), 1378–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yerke AF, & Mitchell V (2013). Transgender people in the military: don’t ask? Don’t tell? Don’t enlist!. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(2–3), 436–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coon D, Neira PM, & Lau BD (2018). Threats to United States fully reviewed and strategic plan for integration of transgender military members into the armed forces. American Journal of Public Health, 108, 7, 892–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elders MJ, Brown GR, Coleman E, Kolditz TA, & Steinman AM (2015). Medical aspects of transgender military service. Armed Forces & Society, 41(2), 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan L (2011). Transgender health at the crossroads: legal norms, insurance markets, and the threat of healthcare reform. Yale J. Health Pol’y L. & Ethics, 11, 375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, Garofalo R, Hembree W, Radix A, & Sevelius J (2016). Barriers to health care for transgender individuals. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity, 23(2), 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American journal of public health, 103(5), 943–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stotzer RL (2009). Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poteat T, German D, & Kerrigan D (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer IH, Brown TN, Herman JL, Reisner SL, & Bockting WO (2017). Demographic characteristics and health status of transgender adults in select US regions: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2014. American journal of public health, 107(4), 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streed CG, McCarthy EP, Haas JS (2017). Association between gender minority status and self-reported physical and mental health in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(8), 1210–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N, & HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. (2008). Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 12(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos GM, Rapues J, Wilson EC, Macias O, Packer T, Colfax G, & Raymond HF (2014). Alcohol and substance use among transgender women in San Francisco: prevalence and association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Drug and alcohol review, 33(3), 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Oldenburg CE, & Bockting W (2015). Individual-and structural-level risk factors for suicide attempts among transgender adults. Behavioral Medicine, 41(3), 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisner SL, Hughto JMW, Dunham EE, Heflin KJ, Begenyi JBG, Coffey- Esquivel J, & Cahill S (2015). Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. The Milbank Quarterly, 93(3), 484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Hwahng S, Mason M, Macri M, & Becker J (2015). Gender abuse and incident HIV/STI among transgender women in New York city: buffering effect of involvement in a transgender community. AIDS and Behavior, 19(8), 1446–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budge SL, Adelson JL, & Howard KA (2013a). Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: the roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 81(3), 545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budge SL, Katz-Wise SL, Tebbe EN, Howard KA, Schneider CL, & Rodriguez A (2013b). Transgender emotional and coping processes: Facilitative and avoidant coping throughout gender transitioning. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4), 601–647. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masten AS (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American psychologist, 56(3), 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh AA (2012). Transgender youth of color and resilience: Negotiating oppression, finding support. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 68, 690–702. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0149-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Budge SL, Rossman HK, & Howard KA (2014). Coping and psychological distress among genderqueer individuals: The moderating effect of social support. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 8(1), 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh AA, Hays DG, & Watson L (2011). Strategies in the face of adversity: Resilience strategies of transgender individuals. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89, 20–27. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00057.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh AA, & McKleroy VS (2011). “Just getting out of bed is a revolutionary act”: The resilience of transgender people of color who have survived traumatic life events. Traumatology, 20(10), 1–11. doi: 10.1177/1534765610369261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnett BS, Nesbit AE, & Sorrentino RM (2018). The transgender bathroom debate at the intersection of politics, law, ethics, and science. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 46(2), 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleming MB, & McFadden-Wade G (2018). The legal implications under federal law when states enact biology-based transgender bathroom laws for students and employees. Hastings Women’s Law Journal, 29(2), 157. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obes ED (2018). Transgender health: access to care under threat. Endocrinology, 6, 443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahill SR, & Makadon HJ (2017). If they don’t count us, we don’t count: Trump administration rolls back sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. LGBT health, 4(3), 171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackman Kasey B., Dolezal Curtis, Levin Bruce, Honig Judy C., and Bockting Walter O.. “Stigma, gender dysphoria, and nonsuicidal self-injury in a community sample of transgender individuals.” Psychiatry research 269 (2018): 602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guest G, Bunce A, & Johnson L (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Equaldex (2018). Compare LGBT rights in Georgia, New York, & California. Retrived from https://www.equaldex.com/compare/georgia-state/new-york/california

- 40.Human Rights Campaign. Municipal Equality Index. A nationwide evaluation of municipal law. (2018). Retrived from https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/MEI-2018-FullReport.pdf?_ga=2.52405737.1780528745.1543261534-1236434318.1543261534

- 41.Biden J (2018). Foreword in McBride, S., Tomorrow will be different: Love, loss, and the fight for trans equality. Crowne Archetype. [Google Scholar]

- 42.King MLK Jr. (1965). Speech given at the capitol steps. Selma, Alabama. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veldhuis CB, Drabble L, Riggle ED, Wootton AR, & Hughes TL (2018). “We won’t go back into the closet now without one hell of a fight”: Effects of the 2016 presidential election on sexual minority women’s and gender minorities’ stigma-related concerns. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, Wong S, Geiger E, & Soderstrom B (2015). Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MS, & Gray SW (2009). The courage to challenge: A new measure of hardiness in LGBT adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(1), 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riggle ED, Rostosky SS, Drabble L, Veldhuis CB, & Hughes TL (2018). Sexual minority women’s and gender-diverse individuals’ hope and empowerment responses to the 2016 presidential election. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaid U (2012). Irresistible revolution: Confronting race, class and the assumptions of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender politics. Magnus Books. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, … & Monstrey S (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]