Abstract

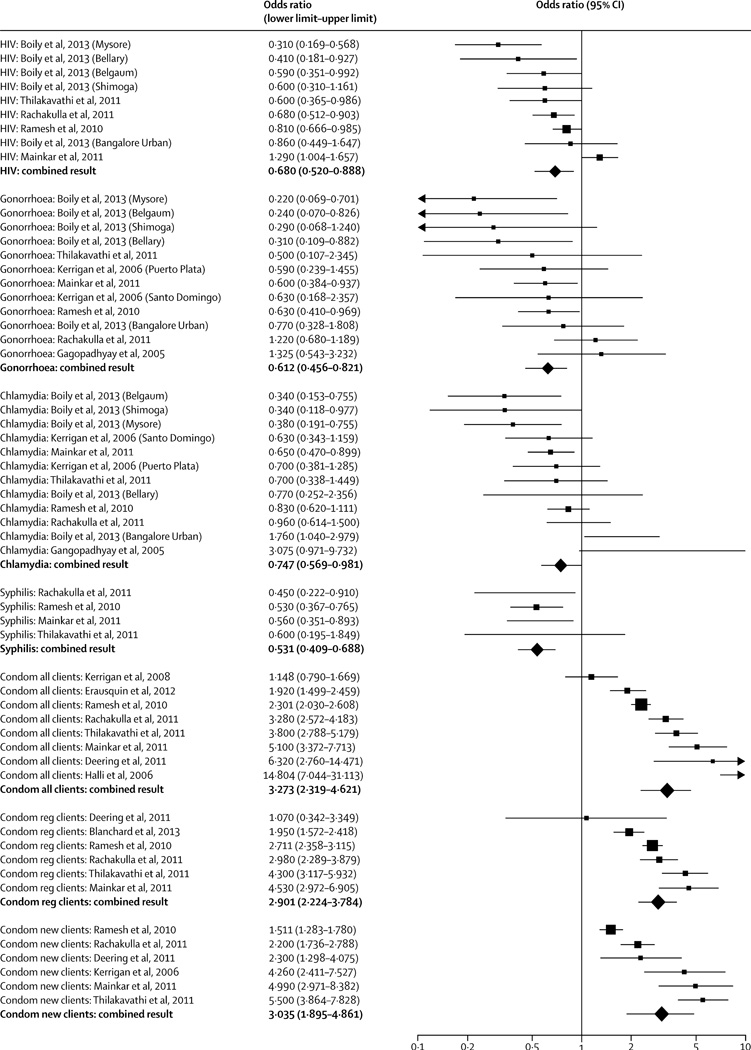

A community empowerment-based response to HIV is a process by which sex workers take collective ownership of programs to achieve the most effective HIV outcomes and address social and structural barriers to their overall health and human rights. Community empowerment has increasingly gained recognition as a key approach to addressing HIV among sex workers with its focus on addressing the broader context within which their heightened risk for infection occurs. However, large-scale implementation of community empowerment-based approaches has been limited. We conducted a comprehensive review of community empowerment approaches to addressing HIV among sex workers. Within this effort, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of community empowerment among sex workers in low- and middle-income countries. The systematic review yielded studies including 30,325 participants; however, evaluations from only 8 projects in 3 countries met the eligibility criteria. In meta-analysis, community empowerment was associated with reductions in HIV (odds ratio [OR]: 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52–0.89), gonorrhea (OR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.82), chlamydia (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57, 0.98), and high-titre syphilis (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.41, 0.69) and increased consistent condom use with clients (OR: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.32, 4.62). Given the relatively weak study designs and limited geography of the studies, findings do not definitely demonstrate the expected effects of community empowerment across settings, but do indicate consistently positive trends. Despite the promise of a community-empowerment approach, our comprehensive review documented formidable structural barriers to implementation and scale-up at multiple levels. These barriers include regressive international discourses and funding constraints, national laws criminalising sex work, and intersecting social stigmas, discrimination and violence. Findings indicate the need to strengthen and diversify the evidence base for community empowerment among sex workers, including its role in facilitating access to and uptake of combination HIV prevention interventions. Results also point to the need for social and political change regarding the recognition of sex work as work, globally and locally, to stimulate greater support for community empowerment responses to HIV.

Keywords: community empowerment, sex work, HIV, STI, condom use, structural

Introduction

From the beginning of the HIV epidemic, sex workers have been known to be at dramatically increased risk for HIV infection. The disproportionate burden of disease experienced by sex workers has recently been further highlighted drawing on epidemiologic data from numerous geographic settings and epidemic types.1 Despite the global expansion of access to care and treatment, sex workers living with HIV continue to face significant barriers to accessing services2–10 as well as poorer treatment outcomes.11,12 These findings indicate that sex workers are exposed to a unique set of factors impeding their health and necessitating increased attention within the global response to HIV.

The context of sex workers’ heightened risk for HIV is characterized by numerous social and structural constraints.13–15 Sex work is criminalized in some form in 116 countries.16 In many settings, laws, policies, and local ordinances all serve to penalize and marginalize sex workers and exclude them from national HIV responses.17 Sex workers experience violations of their human and labour rights. They are also frequently exposed to intersecting social stigmas, discrimination and violence related to their occupation, gender, socio-economic position and HIV status.1,15,18–21 Without addressing these powerful structural challenges, the HIV response among sex workers is likely to be ineffective and unsustainable.

A community empowerment-based response to HIV is a process by which sex workers take collective ownership of programs to achieve the most effective HIV outcomes and address social and structural barriers to their health and human rights. These efforts are unique in that they are driven by the needs and priorities of sex workers themselves, coming together as a community. Community empowerment among sex workers has been recognized as a UNAIDS Best Practice for over a decade,22 and continues to underpin numerous key UN policy documents regarding HIV among sex workers.21,23 Evaluations of community empowerment conducted across multiple countries have shown it tobe a promising approach to reduce HIV risk among sex workers.24 Recent mathematical modeling suggests that community empowerment efforts can significantly reduce HIV incidence among sex workers, as well as the general adult population across diverse HIV epidemic scenarios, and that these interventions are cost-effective.1,25 Despite the growing body of encouraging evidence, government and donor investment in community empowerment-based approaches among sex workers has been limited.26,27

We conducted a comprehensive review of both the peer-reviewed and practice-based literature on the implementation, effectiveness, and barriers and facilitators of community empowerment-based HIV prevention among sex workers. Nested within this comprehensive review, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of community empowerment among sex workers on key HIV-related outcomes. We also present four case studies highlighting the social and structural challenges faced by sex workers across settings and their collective responses to reduce their risk for HIV infection and promote their overall health and human rights.

Search strategy and review methods (text box)

Comprehensive review

Working collaboratively as researchers and sex worker community members, we conducted a comprehensive search of the peer-reviewed and practice-based evidence on community empowerment-based responses to HIV among sex workers. For practice-based evidence, we searched online for and solicited programme reports and presentations from a variety of organisations working on sex work and HIV prevention, including the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) listserv. For peer-reviewed literature, we searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, EMBASE, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) using a combination of terms for sex work, HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STI), and community empowerment (including terms such as social cohesion, mobilisation, solidarity, collective, and rights). Additionally, we reviewed a World Health Organisation database of articles on sex work and HIV, screened reference lists of included articles, and contacted experts to identify additional articles. Searches focused on literature in all languages published between January 1, 2003 and February 1, 2013. To examine the barriers and facilitators of community empowerment initiatives, we abstracted and compiled data gathered from both the peer-reviewed and practice-based literature, using a priori and emergent categories at the global, state and community level of analysis. We also synthesised the literature on the measurement and monitoring of a community empowerment.

Systematic review

To assess the evidence of effectiveness of community empowerment interventions, we updated a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of pre/post or multi-arm evaluations of community empowerment-based HIV prevention interventions among sex workers in low- and middle-income countries.24 Key outcomes of interest included HIV infection, STI infection, and condom use with clients. Data were abstracted in duplicate using standardized forms. Random effects models were used to meta-analyse data across studies with heterogeneity assessed by the I2 statistic. We excluded duplicative data (data from the same participants reported in multiple articles) from meta-analysis. Further details of the search strategy, systematic review and meta-analysis methods are available in an online appendix.

Case studies

We developed case studies on four sex worker-led projects from Kenya, Myanmar, India, and Brazil. Authors involved in each of these programmes drew on project documents, conferred with community members, and reflected on their experiences over time. In the case of Kenya (PM) and Myanmar (KTW), the case studies were developed by sex workers themselves, whereas the case studies from India (SRP) and Brazil (DK) are from the perspective of collaborating academic partners engaged in research in those settings. Key elements of the context, process, barriers and facilitators, and sustainability of community empowerment are described in these four case studies. Two of these case studies describe in detail projects that were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis, in the case of India with the Avahan project representing 13/22 articles in the review and the Encontros and Fio da Alma projects from Brazil reflected in 2/22 articles.

What is community empowerment?

Our comprehensive review found that community empowerment-based HIV responses are distinguished from typical HIV prevention programming in several ways. First, community empowerment approaches do not merely consult sex workers, but rather are community-led, such that they are designed, implemented, and evaluated by sex workers. Second, they recognise sex work as work–as a legitimate occupation or livelihood–and seek to promote and protect its legal status as such. Third, they do not seek to rehabilitate, rescue, or remove sex workers from their profession. Instead, they are committed to ensuring the health and human rights of sex workers as workers and as human beings. Rather than positioning sex work as sexual violence, conflating sex work with human trafficking, or framing sex workers as “victims” or “vectors” of disease, a community empowerment response to HIV is grounded in sex workers’ experiences, insights, and leadership.21,28

In practical terms, the process of community empowerment often begins with sex workers meeting in a safe space to share their experiences, prioritize shared needs, and problem solve to jointly address barriers to their health and well-being, including but not limited to their heightened risk for HIV. Community empowerment is a social movement in which sex workers come together as a community developing internal cohesion, then mobilising their collective power and resources to articulate, and as necessary demand, their human rights and entitlements. In this process, sex worker communities seek allies, including governmental and non-governmental groups, and challenge groups and individuals who inhibit progress to achieve social and policy change and expand access to quality HIV services. The formation of a sex worker rights organisation is often the outgrowth of a community empowerment process whose shape, speed, and focus varies by the socio-political, historical, and legal environment in which it takes place.

Community empowerment among sex workers is thus an overall approach, rather than a set of specific intervention activities. Within this approach, a variety of HIV prevention, treatment, and care and support strategies can be implemented. Specific intervention elements may include biomedical components (e.g., HIV and STI counseling and testing, linkages to care and treatment), behavioural components (e.g., sex worker-led outreach and community education, condom distribution), and structural components (e.g., social cohesion and community mobilisation, access to justice, socio-economic opportunities).29

Is community empowerment effective?

Our systematic review identified 5,457 unique citations, of which 22 peer-reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria for having conducted evaluations of the effectiveness of community empowerment-based HIV prevention interventions among sex workers over the last ten years, from February 1, 2003 to January 31, 2013 (Table 1).30–51 The number of included publications more than doubled since our previous review (n=10) that included articles published between January 1, 1990 and October 15, 2010, largely reflecting recent publications from the Avahan project in India. The 22 articles included in our current systematic review represented 30,325 sex worker study participants from eight projects across three countries: India (17 articles), Brazil (4 articles), and the Dominican Republic (1 article) (Table 1). Thirteen of the 22 articles were from the Avahan project in India. While all projects included female sex workers, only one project from Brazil also included male and transgender sex workers.33,40 The majority of studies included in the systematic review involved both establishment and non-establishment based sex workers.

| Country | Population | Study design | Outcomes | Sample size | Sampling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sonagachi Project | ||||||

| Basu et al, 2004 | India | Female sex workers | Group randomised trial | Condom use with all clients | N-200 (100 per study group) |

Random selection of participants |

| Gangopadhyay et al, 2005 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Gonorrhoea; chlamydia | N-342 (173 intervention, 169 control group) |

Involved a mix of random and non-random selection of participants |

| Belgaum Integrated Rural Development Society (BIRDS) | ||||||

| Halli et al, 2006 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N-1512 | Random selection of participants |

| Frontiers Prevention Project (FPP) | ||||||

| Gutierrez et al, 2010 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N=3442 (round 1), N=2147 (round 2) |

Non-random selection

of participants |

| Avahan | ||||||

| Adhikary et al, 2012 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; high-titre syphilis; chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=7828 (round 1), N=7806 (round 2) |

Random selection of participants |

| Blanchard et al, 2013 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with regular clients |

N=1750 | Random selection of participants |

| Blankenship et al, 2008 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=812 | Non-random selection

of participants (respondent-driven sampling) |

| Boily et al, 2013 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; chlamydia; gonorrhoea | N=2284 (round 1), N=2378 (round 2), N=2359 (round 3) |

Random selection of participants |

| Deering et al, 2011 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with regular clients and new clients |

N=775 | Random selection of participants |

| Erausquin et al, 2012 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N=794 (round 1), N=669 (round 2), N=813 (round 3) |

Random selection of participants |

| Guha et al, 2012 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N=9111 | Random selection of participants |

| Mainkar et al, 2011 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; high-titre syphilis; chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=2525 (round 1), N=2525 (round 2) |

Random selection of participants |

| Rachakulla et al, 2011 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=3271 (round 1), N=3225 (round 2) |

Random selection of participants |

| Ramakrishnan et al, 2010 | India | Female sex workers | Cross-sectional study | Condom use with regular clients and new clients |

N=9667 | Random selection of participants |

| Ramesh et al, 2010 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; high-titre syphilis; chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=2312 (round 1), N=2400 (round 2) |

Random selection

of participants (conventional duster and time- location cluster sampling) |

| Reza-Paul et al, 2008 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; high-titre syphilis; chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=429 (round 1), N=425 (round 2) |

Random selection

of participants (time-location cluster sampling) |

| Thilakavathi et al, 2011 | India | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | HIV; high-titre syphilis; chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with all clients, regular clients, and new clients |

N=2032 (round 1), N=2006 (round 2) |

Random selection of participants |

| Encontros | ||||||

| Lippman et al, 2012 | Brazil | Female, male, and transvestite sex workers |

Prospective cohort study | Chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with regular clients and new clients |

N=420 | Non-random selection

of participants |

| Lippman et al, 2010 | Brazil | Female, male, and transvestite sex workers |

Prospective cohort study | Chlamydia; gonorrhoea | N=420 | Non-random selection

of participants |

| Fio da Alma | ||||||

| Kerrigan et al, 2008 | Brazil | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N=499 (round 1), N=537 (round 2) |

Non-random selection

of participants |

| Projeto Princesinha | ||||||

| Benzaken et al, 2007 | Brazil | Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | Condom use with all clients | N=148 (round 1); N=139 (round 2) |

Non-random selection

of participants |

| Compromiso Colectivo | ||||||

| Kerrigan et al, 2006 | Dominican Republic |

Female sex workers | Serial cross-sectional study | Chlamydia; gonorrhoea; condom use with new clients |

Santo Domingo: N=210 (round 1), N=206 (round 2) Puerto Plata: N=200 (round 1), N=200 (round 2) |

Random selection of participants |

Most studies included in the systematic review incorporated or intensified community empowerment within existing programmes. The existing programmes all included traditional HIV prevention activities, including community-led peer education, condom distribution, and the promotion of periodic STI screening. The evaluations then assessed the additional impact of community empowerment, above and beyond these traditional HIV prevention approaches, either by measuring changes in outcomes over time as a community empowerment approach was added or intensified, or by comparing varying levels of exposure to empowerment activities. However, the included programmes did vary in the specific nature of their activities, and in the extent to which they fully operationalized the ideals and principles of community empowerment, including ownership and project design and management by sex worker-led groups.

One randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in West Bengal, India,34 which had high or uncertain risk of bias across all Cochrane Collaboration tool items. With the exception of one longitudinal study from Brazil,33,40 the remaining studies all used cross-sectional or serial cross-sectional designs. Because the evidence base reflects relatively weak study designs, our ability to draw causal inferences and firmly establish the effectiveness of community empowerment is limited.

In meta-analysis, community empowerment-based responses to HIV among sex workers were consistently associated with statistically significant reductions in HIV and STIs and increases in condom use outcomes. Detailed results are presented for each outcome.

HIV infection

HIV infection was measured in five articles. All were serial cross-sectional studies from the Avahan project in India, and all measured HIV prevalence, not incidence.41,43,45,46,48 In meta-analysis, these studies showed a combined reduction in HIV prevalence among sex workers following the implementation of community empowerment efforts (OR=0·680; 95% CI: 0·520, 0·888, I2=73.897, p=0.000) (Figure 1). Heterogeneity was high.

Figure 1.

STI infection

STI incidence was measured in one longitudinal study conducted in Brazil.33,40 Although over half of participants were lost to follow-up by study end, inverse probability weighting was used to minimize potential biases. The study showed a nonsignificant reduction in combined gonorrhea and chlamydia prevalence from baseline to 12-month follow-up (Crude OR=0·46; 95% CI: 0·2–1·3).33

Eight additional cross-sectional or serial cross-sectional articles were included in meta-analyses for STI infection.36,38,41,43,45,46,48,52 Combined results showed that community empowerment was associated with a significantly decreased odds of gonorrhea (7 studies; OR=0·612; 95% CI: 0·456, 0·821; I2=32·511, p=0.130), chlamydia (7 studies; OR=0·747; 95% CI: 0·569, 0·981; I2=61·045, p=0.003), and high-titre syphilis (5 studies; OR=0·528; 95% CI: 0·410, 0·678; I2=0, p=0.959). Heterogeneity was high for meta-analyses of gonorrhea and chlamydia, but not for syphilis, which also showed the strongest effect (the odds of syphilis were almost reduced by half with a community empowerment approach).

Condom use

Condom use was measured in the one RCT.34 This study, conducted in India, randomized two clusters, one to community empowerment and one to control. The regression coefficient (Beta) of 0·3447 (p=0·002) indicated a statistically significant improvement in condom use with clients over time among intervention participants compared to control participants. Condom use was also measured in the longitudinal study from Brazil. This study showed statistically significant increases in consistent condom use in the last 30 days with regular clients (OR=1·9; 95% CI: 1·1, 3·3), but not with new clients (OR=1·6; 95% CI: 0·9, 2·8) where condom use was already high.

Eight additional cross-sectional or serial cross-sectional articles were included in meta-analyses for condom use. 31,37,39,41,43,45–47 Combined results showed that community empowerment was associated with significantly higher odds of consistent condom use with new clients (6 studies; OR: 3·035; 95% CI: 1·895, 4·861; I2=91·767, p=0.000), regular clients (6 studies; OR: 2·901; 95% CI: 2·224, 3·784; I2=80·480, p=0.000), and all clients (8 studies, OR: 3·273; 95% CI: 2·319, 4·621; I2=90·353, p=0.000). Heterogeneity was high for all condom use meta-analyses.

How is community empowerment measured?

To date, most efforts to measure community empowerment have focused on the specific intervention activities conducted, while there has been less focus on the measurement of community empowerment as a social process. For example, the majority of articles in our systematic review measured intervention exposure by assessing whether participants had been contacted by a peer educator, received condoms or other educational materials, visited drop-in centres or health clinics, or participated in group workshops, meetings, or other activities. Similarly, programme monitoring indicators reported in the 22 systematic review articles generally focused on the coverage and quality of clinical and community-based HIV services offered to sex workers rather than documentation of the community empowerment process. The Avahan project, however, did implement a more comprehensive monitoring plan of its community mobilisation programmes, including those with sex workers. The Community Ownership and Preparedness Index (COPI) was designed as a way to document the progress of community mobilisation and the transition of responsibility to participating community groups including sex worker organisations.61, 62 The parameters of the COPI include leadership, governance, decision making, resource mobilisation, networking, programme management, engagement with the state to secure rights and entitlements, and engagement with the wider society to reduce sex work-related stigma.62

Some projects attempted to document the social process associated with community empowerment among sex workers using both individual indicators and aggregate measures. Of the 22 articles in our systematic review, two used single item indicators to capture the social process stimulated by the community empowerment intervention, including constructs such as collective identity, support, efficacy and agency.32,35 Five of the 22 studies utilized more theoretically complex aggregate measures to assess the dynamic process of community empowerment, from the formation of internal community cohesion within the sex worker community to the social and political participation of sex workers as a group, and, as a result, their broader social inclusion in society, including their access to health, social and economic resources.33,37–39,49 Additionally, some projects documented the progression of sex worker collectivisation and participation in sex worker-led organisations.37,39 Finally, in addition to the development of collective resources and power (over), increased personal agency and power (within) have been included as important measures of the process of community empowerment.49

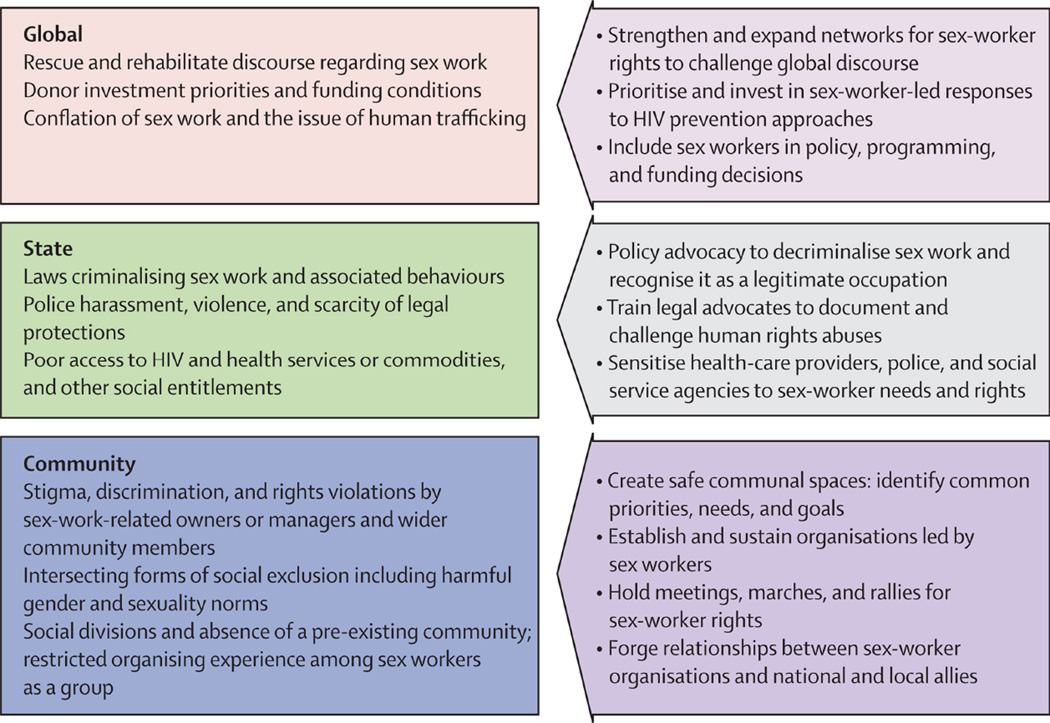

What are the barriers and facilitators to community empowerment?

Our comprehensive review found 110 documents from both the peer and practice-based evidence related to implementation of community empowerment-based responses to HIV among sex workers across settings. From this literature, we sought to identify the most salient barriers to implementation and scale-up at the global, state, and community levels as portrayed in Figure 2. Additionally, we sought to capture facilitating factors and innovative responses employed by sex worker programmes to overcome these challenges. At the global level, international policies and funding mechanisms can facilitate or hinder community empowerment. Policies that hinder the community empowerment process include the global “raid and rescue” discourse, in which non-sex workers characterize sex workers as passive victims needing rescue.21,63,64 These programmes often deny sex workers’ agency in choosing their livelihoods and undermine the legitimacy of sex work as work. Additionally, this discourse often conflates consensual adult sex work with human trafficking. The United States Government’s anti-prostitution pledge also hindered community empowerment processes by stipulating that organisations receiving PEPFAR money must sign a pledge against prostitution. Reports suggested that the pledge harmed sex workers and promoted stigma and discrimination65 while reducing the effectiveness of HIV prevention programmes and services for sex workers.66 The pledge was ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in June, 2013. Finally, while some international donors do advocate for community empowerment, they often still hold programmes accountable to management requirements that are difficult for sex worker community members or groups to maintain, thus limiting sex worker’s actual authority and decision-making power in developing, implementing, and evaluating programmes.67

Figure 2.

There are also factors facilitating community empowerment at the global level. For example, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) unites 160 sex worker groups from 60 countries and stimulates dialogue and debate related to international policies and funding practices that influence sex worker’s health and human rights. Building on there commendations of the recent report from the Global Commission on HIV and the Law,68 NSWP’s recent consensus statement calls for the full decriminalization of sex work to promote and protect sex workers’ human rights, including reducing their increased risk for HIV.69 In just the past few years, several United Nations agencies and other international organisations have called for decriminalization of sex work as an integral part of the HIV response for sex workers.21, 29, 70–72

Moving from the global to the national, the state strongly influences the health and human rights of sex workers and their ability to implement community empowerment approaches. National laws criminalising sex work or activities related to sex work can impede sex workers’ ability to organize and increase stigma, discrimination and violence among sex workers. 16,73 Efforts to decriminalize sex work are active in many countries and some important successes have occurred in the area of national laws and policies related to sex work. For example in Brazil, the sex worker rights movement worked to secure sex work as a recognised occupation and sex workers are now legally entitled to claim critical labour rights such as pensions.74 Initiatives to involve the police in sensitivity trainings have also been successful.75,76 For example in India, as a result of experiencing police violence, sex workers from Ashodaya Samithi organised trainings for local law enforcement, which culminated in police officers joining sex workers in solidarity at a rally to protest a law detrimental to sex workers.75 The Avahan project created crisis intervention teams that began policing the police by having sex workers report and document police abuses, thus leading to decreased violence.77 Sex workers have also turned policies and injustices that hinder empowerment into reasons for community mobilisation that facilitate empowerment.78–80 For example, the murder of a transgendered sex worker in Brazil led to a public demonstration to address sex work-related violence, which was seen as a critical initial step in developing group-level consciousness for further collective action to address health and human rights.79

At the community level, sex workers are frequently exposed to stigma, discrimination and violence – often by law enforcement officials, owners and managers, and sometimes by clients.75,76,81–84 They also experience socio-economic exclusion;84,85 denial of health care;76,84,86,87 stigmatization and discrimination by friends, family, neighbours, and social and religious institutions;79,82,88 and difficulty accessing social entitlements.64,86,87 For these reasons, many individuals who practice sex work do so in secret and are unwilling to be recognised as sex workers.89–91 This stigma-fuelled denial of selling sex hampers community empowerment by discouraging some individuals from joining organisations openly focusing on sex workers. In places where sex work is illegal, sex workers may also avoid sex work organisations for fear of police reprisal.92

Sex workers are diverse.93 They come from different socio-economic, ethnic, and regional backgrounds. They are often mobile or undocumented migrants and they work in different venues and spaces, including brothels, bars, or on the street.28,94,95 There is also social stratification among sex workers and competition for clients28,96 all of which can lead to mistrust and disunity,97 hampering community empowerment efforts. Finding common interests is a necessary but not sufficient part of building social cohesion and creating collective action.94 The Sonagachi Project and SANGRAM/VAMP initiative found that community-led outreach and peer educators helped sex workers identify shared experiences and needs and facilitated community building.28,98,99 In the Ashodaya Simithi project in Mysore, India, sex workers built cohesion when they openly began identifying as sex workers and mobilising around the idea that sex work is legitimate work.100 Many projects build infrastructure, often in the form of drop-in centres that give sex workers physical space allowing them to come together and form bonds.39,96,101–103

In addition to building social cohesion among sex workers, forging relationships with potential allies and partners is critical, especially as the stigma, discrimination, and disempowering circumstances faced by sex workers are driven by outside groups.89 Some initiatives have had great success working with powerful actors, such as brothel owners and managers and influential local clubs and political groups,104 while others have found it more difficult, noting that outside groups have little incentive to join initiatives aimed at empowering sex workers.96 Promoting social acceptance of sex workers by involving members of the larger community in sex worker events, rallies, and other social mobilisation activities has also been linked to facilitating community empowerment.28

Across these different levels, building an enabling environment for sex workers is key to facilitating community empowerment. This involves giving voice to those affected by unequal social conditions and fostering the ability to challenge such conditions.105 Therefore, building leadership and capacity among sex workers within community empowerment interventions is crucial. For example, the Sonagachi Project fostered capacity building by promoting a sense of equality between sex workers and project staff and adapting the project to serve the needs and priorities identified by sex workers themselves.28 Ashodaya Samithi fostered leadership by allowing sex workers to make key decisions in creating a health centre to serve their needs.106 Groups can also promote autonomy and leadership by networking with other sex worker groups regionally, nationally, or internationally and by linking with other movements, such as labour rights, women’s rights, and human rights.107 Although non-sex worker-led organisations, such as international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), may play important roles in community empowerment initiatives, particularly in the initial stages of community organising, some suggest their role should be supportive in nature, rather than directive, or else they too may inhibit the community empowerment process.108 Together, this literature suggests that the community empowerment process must be envisioned, shaped and led by sex workers themselves if it is to be effective and sustainable in reducing sex workers’ risk for HIV and promoting and protecting their health and human rights.

Text Boxes

Kenya: “Now, some police have not bothered messing with the girls because they have their mother in Nairobi”

In bars outside Nairobi, Kenya, sex workers experienced persistent violence and HIV risk, yet the stigma surrounding HIV meant that sex workers rarely discussed HIV and were often ignorant of even the most basic facts about HIV transmission. The Bar Hostess Empowerment and Support Programme (BHESP) was founded in 2001 when a small group of bar hostesses and sex workers were organized and trained on HIV prevention and care. BHESP now has over 3,000 members with a network of 42 different local groups across four provinces in Kenya. Each of the local groups is independently formed and is unique in terms of location and client type.

BHESP activities include drop-in centres for health education and other HIV and STI services; community-led educators; care and support for sex workers living with HIV; and opportunities for the mobilization and capacity building of sex workers. Although BHESP’s initial focus was HIV, the women considered violence, sometimes murder, by police, managers, and some bar customers and sex worker’s clients as a bigger and more immediate problem. To them HIV was less of an immediate threat on a daily basis.

BHESP confronts these abuses by going directly to the police and to the courts, advocating against police brutality in public and through mass media. Sex workers have now been trained as paralegals to educate their peers on their rights. Women are often arrested for loitering, carrying condoms, or being dressed as if they had an “immoral purpose” as evidence of intent to sell sex.

Prior to the establishment of BHESP, women would often bribe the police or plead guilty and pay a fine. Now, the BHESP paralegals advise women to plead innocence and to take the case to court. Between January and June 2013, 105 cases of violence and arbitrary arrest of sex workers were reported to BHESP. With the help of lawyers, BHESP won all of these cases, which eventually went before the court.

In addition, BHESP advocates for decriminalisation of sex work at the local level, city by city. BHSEP monitors the number of cases of abuse and arrests that are reported through their hotline, whether cases go to court, and whether arrests have stopped or decreased as a result of BHSEP’s interventions. These active community empowerment interventions have resulted in a decrease of police harassment of sex workers; police realize that their actions are likely to result in an unnecessary confrontation with BHSEP and the likelihood of being taken to court.

Myanmar: “I came from the community, so I work for the community”

In 2004 there were some existing HIV programmes in Myanmar but none specifically for sex workers, despite high HIV prevalence among sex workers, including those who had worked in Thailand. The sex worker community faced significant stigma and there was a general lack of dialogue about the health and rights of sex workers. The Targeted Outreach Project (TOP) was started in the capital city, Yangon, and has grown to 18 cities reaching over 62,000 sex workers per year. In Yangon, TOP established drop-in centres where sex workers could access free health care, without the stigma that they often encountered from other health care providers. The care, support and other services provided at the centres are a holistic package, not solely focused on HIV or STIs. Importantly, community educators are sex workers from the communities that they serve. After establishing the early drop-in-centres, TOP became more sophisticated and developed an approach that was inclusive of sex workers, the neighbouring community, the Health Department, and local authorities, engaging all partners from the outset. TOP had to overcome local opposition in some neighbourhoods to the establishment of drop-in-centres. Understanding the stigma attached to sex work TOP put on theatrical performances depicting the lives of sex workers to win over the neighbours.

TOP provides the technical and financial support for opening new centres, but insists that local sex workers take responsibility and control over their own centres through empowerment, advocacy, and emotional support. TOP monitors their performance, and does so in a way that is easy and accessible to sex workers. In monitoring condom use by sex workers with clients at last sex, for instance, TOP has instituted a simple system. At the centre there is a coupon box with three different colours of coupons from which to choose. Red signifies no condom use during last sex, green means a condom was used, and yellow indicates non-penetrative sex during last sexual encounter. When sex workers come in for any centre services, they choose the appropriate coupon colour and place it in the box. Coupons are then counted at the end of the month to determine the percent using condoms. TOP continues to work towards their main goals: freedom from the stigma and violence sex workers consistently face; and affordable and accessible health services. The TOP programme recognizes that sex workers will have different levels of interest in engaging in the programmes. However, they contend, that all sex workers must be given the opportunity to actively participate in all levels of decision making.

India: From “For the community” to “With the community” to “By the community”

In 2004, researchers from the University of Manitoba conducted an assessment among sex workers in Karnataka, India that highlighted the need for safe space, violence reduction and basic health services. Credibility with the community was gained by setting up a 12-week plan to roll out services. This initial phase involved a “for the community” approach driven by external agents. Soon, it was clear that the project needed to work “with the community,” involving sex workers in all aspects of the project including decision-making. This phase saw a high degree of community mobilization among sex workers including their coming together for public events and celebrations. Within a year of the assessment, an organisation of sex workers, Ashodaya Samithi (Dawn of Hope), was born with a democratically elected executive board. In the move from “us” researchers as external agents doing something for “them” to researchers and the community working together, it became evident over time that the organisation of sex workers was ready to move to the next level of doing it by themselves or “by the community”. In its second year, Ashodaya was able to take on most of the core elements of the project. Within three years, over 4,000 sex workers had become members, monitoring showed a saturation in intervention coverage, and Integrated Biological and Behaviour Assessments (IBBA) showed progress on HIV outcomes such as increases in condom use and decreases in STIs. The university group was not only playing a facilitator role but was bringing science to sex workers and deconstructing it in such a way that they were able to use it. Capture-Recapture size estimation allowed the community to see that they had strength in numbers and that together they could form a constituency. The IBBA helped them understand that HIV is real, that there were sex workers among them who were HIV-infected, and that protection is critical. Sex workers not only owned the data generated, but owned the response. By 2007 Ashodaya had started organised dissemination of its model through a community-to-community learning programme to help strengthen other sex worker organisations. It offers technical assistance to various sex workers groups and organisations as a national learning site. Soon it became a regional learning site, maturing into the Ashodaya Academy which now offers technical assistance to sex worker organisations in the Asia Pacific region. Currently, through the European Commission (EC), Ashodaya has been entrusted to build capacities for sex workers projects in 3 African countries. In addition, NSWP has recognized the Ashodaya Academy along with VAMP to provide assistance in developing pan-Africa sex workers’ Academy. Today Ashodaya Samithi has over 8,000 members. It has a programme management unit that takes key decisions on programme delivery and a governing board which is comprised of community leaders. The community now runs all programmes and has an annual budget of over 2 million dollars.

Brazil: “Without Shame, You Have an Occupation”

Davida, a sex worker-led NGO, was established in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Davida was founded to promote sex workers’ health and rights as citizens, reduce stigma and violence, and ensure an active role for sex workers in the creation of public policies. Davida, along with the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes which was founded in 1987, give voice and visibility to sex workers’ needs and priorities, including but not limited to HIV prevention. Their approach to health and rights promotion has always been focused creating political, social and cultural change regarding the manner in which sex work was understood and regulated in Brazil. Through advocacy and grass-roots organising, the national network’s efforts led to critical policy changes at the federal level. In 2002, sex work was officially recognised as an occupation in Ministry of Labour’s Occupational Registry, entitling sex workers to social security and other workers benefits. Although the continued illegality of the premises where sex work occurs has made guaranteeing full labour rights difficult, significant progress has been made. Davida’s work also expanded in the socio-cultural and media realms. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Davida partnered with the Brazilian Ministry of Health on ground breaking HIV prevention campaigns centered around respecting the profession and fighting stigma, such as the Maria Sem Vergonha (“Maria, without shame”: you have an occupation) public media campaign. In 2005, it created its own fashion and clothing line called Daspu (“of the whores”) that received wide national and international recognition. Over the last five years, however, national and international support (political and financial) decreased considerably for the Brazilian sex worker rights and community empowerment movement, and in turn, its actions have become more limited in scope. In June of 2013, significant controversy emerged in Brazil over the issue of sex worker human rights and HIV prevention. The Minister of Health vetoed, and then later drastically altered, a rights-based anti-stigma HIV prevention campaign created in partnership between sex workers and the STD/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Department of the Ministry of Health. First, the Minister removed the most controversial poster, which stated, “I am happy being a sex worker (Eusoufelizsendoprostituta)”. After additional political pressure, he vetoed the entire campaign, fired the Director of the STD/AIDS Department and launched a drastically altered version of the campaign focused exclusively on condom use and devoid of any mention of citizenship or rights. Several members of the STD/AIDS Department resigned, while the Prostitutes Network and other civil society groups and researchers organised large-scale mobilisations and letters of protest in response to the government’s actions. These challenges signal the critical importance of sustaining a community empowerment movement among sex workers with both national and international political and financial resources and ongoing collaborative partnerships.

What are the Policy, Program and Research Implications?

Our findings indicate the promise of community empowerment approaches in responding to the significantly higher risk of HIV infection among sex workers. However, results must be interpreted with caution due to the relatively weak research designs and limited geography of the studies involved in our nested meta-analysis. The heterogeneity observed in the effects of community empowerment on specific HIV outcomes is expected given the nature of the approach. However, this heterogeneity further signals the appropriateness of emphasizing the consistent trends observed regarding the effectiveness of community empowerment, rather than the degree of expected impact across settings.

Future studies are needed to more rigorously measure the impact of community empowerment approaches to HIV among sex workers across geographic and epidemic settings on both HIV and non-HIV outcomes. In particular, there is a need to assess the impact and process of community empowerment as a platform for combination HIV prevention interventions that integrate biomedical, behavioral and structural elements. In settings such as sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden of HIV among sex workers is extremely high, there may be opportunities for cluster randomized controlled trials to establish with greater confidence the effects of community empowerment approaches among sex workers on HIV incidence as an endpoint. However, randomized controlled trials are by no means the only type of rigorous research needed moving forward.

There is also a significant need to better measure the community empowerment process utilizing reliable aggregate measures that can be validated across settings. Such measures would assist in further documenting the complex social process of community empowerment and the multiple pathways through which it may lead to social and structural change. Qualitative and ethnographic research must also accompany the implementation of community empowerment approaches among sex workers to understand context specific opportunities and challenges to implementation. There is also a need to expand the practice-based evidence generated by sex worker-led groups.

Significant barriers remain in relation to the broader implementation of community empowerment-based responses to HIV. Our findings indicate that sex work is not yet widely understood as work or a legitimate occupation, and that sex workers continue to be portrayed as individuals who have made poor moral choices or who have been exploited. Whereas advances in thinking regarding the legitimacy of other marginalized populations such as men who have sex with men and drug users have occurred in recent years, the ability to reframe and create a new dialogue on sex work has encountered considerable challenges. This may be in part due to the double standard faced by sex workers, who are often women, and who are seen as violating multiple moral principles in terms of gender and sexuality norms. Divergent perspectives within the women’s movement on the issue of sex work have also played an important role in limiting the ability of the sex workers’ rights movement to gain momentum on this issue, as have the limited resources afforded to sex worker-led organisations and networks.109 Despite these barriers, sex worker organisations have developed innovative and effective strategies to address the multi-level challenges they face in the implementation of community empowerment initiatives to promote their health and human rights. These efforts need greater financial and political support if they are to significantly advance.

Finally, community empowerment approaches among sex workers have had important successes tackling social and structural constraints to protective sexual behaviours and, as a result, reducing behavioural susceptibility to HIV in the context of sex work. New HIV prevention technologies and approaches, such as treatment as prevention, self-testing, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and microbicides, are becoming increasingly available globally. As these efforts expand, they provide an important opportunity for governments, donors, and NGOs to establish meaningful partnerships with sex worker communities and organisations and integrate these initiatives into ongoing community empowerment efforts as one aspect of a combination package of services for sex workers.

Conclusions

The available evidence, while based upon studies from a limited number of projects and countries, indicates that community empowerment shows significant promise as an effective approach to reducing HIV risk among sex workers and that scaling up these initiatives may contribute to curbing the epidemic among sex workers and the general population.1,24,25 Our findings also highlight the deep-rooted paradigmatic challenges associated with expanding community empowerment-based responses to HIV among sex workers. Greater support is needed from donors, governments, partner organisations, and other allies to enable sex worker groups to more effectively and sustainably overcome barriers to implementation and scale-up of a community empowerment approach.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

A community empowerment-based HIV response is a process by which sex workers take collective ownership of programs and services to achieve the most effective HIV responses and address social and structural barriers to their health and human rights.

Community empowerment-based HIV prevention interventions among sex workers are significantly associated with reductions in HIV and STI outcomes and increases in consistent condom use with clients. However, evaluation designs have been relatively weak and geographically limited. Community empowerment approaches to combination HIV prevention among sex workers are rare and should be expanded and evaluated.

Despite the promise of community empowerment approaches to address HIV among sex workers, formidable structural barriers to implementation and scale-up exist at multiple levels. These include: regressive international discourses and funding constraints, national laws criminalising sex work, and intersecting stigmas, discrimination and violence such as those linked to occupation, gender, socio-economic status, and HIV.

Results underscore the need for social and political change regarding the manner in which sex work is understood and addressed including the need to decriminalize sex work and recognize sex work as work. To help achieve these changes, support for sex worker-led networks and community organisations are needed both globally and locally.

There is a need to continue to expand and strengthen the evidence base for community empowerment among sex workers, including study designs focused on better capturing and measuring the process and impact of empowerment efforts across diverse settings, as well as further investments in the generation of sex worker-led, practice-based evidence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the sex workers who led and participated in the research and programmatic efforts which form the basis for this analysis. We thank Gina Dallabetta for her assistance clarifying information about data from the Avahan project; Andrea Blanchard, Kim Blankenship, and Mandar Mainkar for providing additional information about their articles included in the systematic review; and the experts and members of the NSWP listserv who responded to our requests for relevant articles and reports. We appreciate Laura Murray’s help developing the Brazil case study. We would also like to thank the editorial and technical team of the Lancet Series on Sex Work and HIV Prevention as well as the peer reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. This paper and The Lancet Series on HIV and Sex Work was supported by grants to the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; The United Nations Population Fund; and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (1P30AI094189), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

All authors participated in the conceptualisation, development, and writing of the manuscript. DK led conceptualisation of paper, design of analysis, and overall write up. CK led the systematic review and meta-analysis, tables and write-up. RMT provided community-focused framing and feedback on all aspects of manuscript development. SRP, KTW, and PW led the case studies on India, Myanmar, and Kenya, respectively. AM conducted searches for effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and measurement and led the associated write up. VF conducted searchers for barriers and facilitators to implementation and scale-up and led the associated write up. AM and VF extracted data for systematic review articles. JB was the senior author providing technical and conceptual feedback on all aspects of the manuscript particularly framing, language, socio-political context of findings and their implications. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Deanna Kerrigan, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N Broadway St, Baltimore, MD 21205 USA, Phone: +1 410-955-2218, dkerrig1@jhu.edu.

Caitlin E. Kennedy, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Ruth Morgan-Thomas, Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), Edinburgh, Scotland UK.

Sushena Reza-Paul, University of Manitoba, Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

Peninah Mwangi, Bar Hostess Empowerment and Support Program, Nairobi, Kenya.

Kay Thi Win, Targeted Outreach Project, Yangon, Burma.

Allison McFall, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Virginia A. Fonner, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Jennifer Butler, United Nations Population Fund, New York, USA.

References

- 1.Kerrigan D, Wirtz A, Baral S, et al. The Global HIV Epidemics among Sex Workers. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shannon K, Bright V, Duddy J, Tyndall MW. Access and utilization of HIV treatment and services among women sex workers in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(3):488–497. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy C, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, et al. Exploring the Positive, Health, Dignity and Prevention needs of female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgender women in the Dominican Republic and Swaziland. Baltimore, MD: Project SEARCH: Research to Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2013;15(4):450–465. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scambler G, Paoli F. Health work, female sex workers and HIV/AIDS: global and local dimensions of stigma and deviance as barriers to effective interventions. Social science & medicine. 2008;66(8):1848–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghimire L, Teijlingen EV. Barriers to Utilisation of Sexual Health Services by Female Sex Workers in Nepal. Global Journal of Health. 2009;1(1):12–22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Kurian AK, Dubrow R. Barriers to free antiretroviral treatment access for female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(11):973–980. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beyrer C, Baral S, Kerrigan D, El-Bassel N, Bekker LG, Celentano DD. Expanding the space: inclusion of most-at-risk populations in HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 2):S96–S99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821db944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beattie TS, Bhattacharjee P, Suresh M, Isac S, Ramesh BM, Moses S. Personal, interpersonal and structural challenges to accessing HIV testing, treatment and care services among female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgenders in Karnataka state, South India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii42–ii48. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mtetwa S, Busza J, Chidiya S, Mungofa S, Cowan F. “You are wasting our drugs”: health service barriers to HIV treatment for sex workers in Zimbabwe. BMC public health. 2013;13:698. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diabaté S, Zannou DM, Geraldo N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected female sex workers in Benin: a comparative study with patients from the general population. World Journal of AIDS. 2011;1:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huet C, Ouedraogo A, Konate I, et al. Long-term virological, immunological and mortality outcomes in a cohort of HIV-infected female sex workers treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Africa. BMC public health. 2011;11:700. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippman SA, Donini A, Diaz J, Chinaglia M, Reingold A, Kerrigan D. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: the Encontros intervention in Brazil. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S216–S223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park M, Yi H. HIV prevention support ties determine access to HIV testing among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173:S223. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, Devireddy V, Blankenship KM. The context of economic insecurity and its relation to violence and risk factors for HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) 2010;125(Suppl 4):81–89. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed A, Kaplan M, Symington A, Kismodi E. Criminalising consensual sexual behaviour in the context of HIV: consequences, evidence, and leadership. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 3):S357–S369. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.623136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decker MR, Crago A-L, Sherman SG, Dhaliwal M, Beyrer C. Sex work and human rights. The Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beattie TS, Bhattacharjee P, Ramesh BM, et al. Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC public health. 2010;10:476. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, et al. Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2012;88(4):278–283. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swain SN, Saggurti N, Battala M, Verma RK, Jain AK. Experience of violence and adverse reproductive health outcomes, HIV risks among mobile female sex workers in India. BMC public health. 2011;11:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. UNAIDS guidance note on HIV and sex work. Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins C. Female sex worker HIV prevention projects: Lessons learnt from Papua New Guinea, India, and Bangladesh. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2000. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO, UNFPA, UNAIDS, NSWP. Prevention and Treatment of HIV and other Sexually Transmitted Infections for Sex Workers in Low-and Middle-income Countries: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization HIV/AIDS Programme; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerrigan D, Fonner V, Stromdahl S, Kennedy C. Community empowerment among female sex workers is an effective HIV prevention intervention: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed evidence from low and middle-income countries. AIDS and Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirtz AL, Pretorius C, Beyrer C, et al. Epidemic Impacts of a Community Empowerment Intervention for HIV Prevention among Female Sex Workers in Generalized and Concentrated Epidemics. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartlander B, Stover J, Hallett T, et al. Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2011;377(9782):2031–2041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malaria TGFtFATa. Global Fund HIV Investments Specifically Targeting Most-at-Risk Populations: An Analysis of Round 8 (2008) Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandyopadhyay N, Mahendra VS, Kerrigan D, Jana S, Saha MK. The Role of Community Development Approaches in Ensuring the Effectiveness and Sustainability of Interventions to Reduce HIV Transmission through Commercial Sex: Case Study of the Sonagachi Project, Kolkata, India. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.UNDP, UNAIDS. Understanding and acting on critical enablers and development synergies for strategic investments. New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adhikary R, Gautam A, Lenka SR, et al. Decline in unprotected sex & sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among female sex workers from repeated behavioural & biological surveys in three southern States of India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2012;136(SUPPL.):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erausquin JT, Biradavolu M, Reed E, Burroway R, Blankenship KM. Trends in condom use among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: the impact of a community mobilisation intervention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii49–ii54. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guha M, Baschieri A, Bharat S, et al. Risk reduction and perceived collective efficacy and community support among female sex workers in Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, India: the importance of context. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii55–ii61. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lippman SA, Chinaglia M, Donini AA, Diaz J, Reingold A, Kerrigan DL. Findings From Encontros: A Multilevel STI/HIV Intervention to Increase Condom Use, Reduce STI, and Change the Social Environment Among Sex Workers in Brazil. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39(3):209–216. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823b1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. HIV prevention among sex workers in India. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36(3):845–852. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blankenship KM, West BS, Kershaw TS, Biradavolu MR. Power, community mobilization, and condom use practices among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2008;22(SUPPL. 5):S109–S116. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343769.92949.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gangopadhyay DN, Chanda M, Sarkar K, et al. Evaluation of sexually transmitted diseases/human immunodeficiency virus intervention programs for sex workers in Calcutta, India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(11):680–684. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175399.43457.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halli SS, Ramesh BM, O’Neil J, Moses S, Blanchard JF. The role of collectives in STI and HIV/AIDS prevention among female sex workers in Karnataka, India. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2006;18(7):739–749. doi: 10.1080/09540120500466937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, et al. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(1):120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerrigan D, Telles P, Torres H, Overs C, Castle C. Community development and HIV/STI-related vulnerability among female sex workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Health Education Research. 2008;23(1):137–145. doi: 10.1093/her/cym011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippman SA, Shade SB, Hubbard AE. Inverse probability weighting in sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus prevention research: Methods for evaluating social and community interventions. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37(8):512–518. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d73feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramesh BM, Beattie TSH, Shajy I, et al. Changes in risk behaviours and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections following HIV preventive interventions among female sex workers in five districts in Karnataka state, south India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2010;86(SUPPL. 1):i17–i24. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.038513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reza-Paul S, Beattie T, Syed HUR, et al. Declines in risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infection prevalence following a community-led HIV preventive intervention among female sex workers in Mysore, India. AIDS. 2008;22(SUPPL. 5):S91–S100. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343767.08197.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thilakavathi S, Boopathi K, Girish Kumar C, et al. Assessment of the scale, coverage and outcomes of the Avahan HIV prevention program for female sex workers in Tamil Nadu, India: is there evidence of an effect? BMC public health. 2011;11(Suppl 6):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramakrishnan L, Gautam A, Goswami P, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2010;86(SUPPL. 1):i62–i68. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.038760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rachakulla HK, Kodavalla V, Rajkumar H, et al. Condom use and prevalence of syphilis and HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India - following a large-scale HIV prevention intervention. BMC public health. 2011;11(Suppl 6):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mainkar MM, Pardeshi DB, Dale J, et al. Targeted interventions of the Avahan program and their association with intermediate outcomes among female sex workers in Maharashtra, India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 6):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deering KN, Boily MC, Lowndes CM, et al. A dose-response relationship between exposure to a large-scale HIV preventive intervention and consistent condom use with different sexual partners of female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 6):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boily MC, Pickles M, Lowndes CM, et al. Positive impact of a large-scale HIV prevention program among female sex workers and clients in Karnataka state, India. AIDS. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fba81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanchard A, Mohan HL, Shahmanesh M, et al. Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gutierrez J-P, McPherson S, Fakoya A, Matheou A, Bertozzi S. Community-based prevention leads to an increase in condom use and a reduction in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW): the Frontiers Prevention Project (FPP) evaluation results. BMC public health. 2010;10(1):497. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benzaken AS, Galbán Garcia E, Sardinha JCG, Pedrosa VL, Paiva V. Community-based intervention to control STD/AIDS in the Amazon region, Brazil. Revista de saude publica. 2007;41:118–126. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jana S, Bandyopadhyay N, Mukherjee S, Dutta N, Basu I, Saha A. STD/HIV intervention with sex workers in West Bengal, India. AIDS. 1998;12(Suppl B):S101–S108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chandrashkar S, Vassall A, Guinness L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted hiv preventions for female sex workers: An economic evaluation of the avahan programme in Southern India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87:A9. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Commission on AIDS in Asia. Redefining AIDS in Asia: Crafting an Effective Response. New Delhi, India: UNAIDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dandona L, Kumar SP, Kumar GA, Dandona R. Cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions in Andhra Pradesh state of India. BMC health services research. 2010;10(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Rudra S, et al. Cost effectiveness of targeted HIV prevention interventions for female sex workers in India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87(4):354–361. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sweat M, Kerrigan D, Moreno L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of environmental-structural communication interventions for HIV prevention in the female sex industry in the Dominican Republic. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(SUPPL. 2):123–142. doi: 10.1080/10810730600974829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braithwaite RS, Meltzer DO, King JT, Jr, Leslie D, Roberts MS. What does the value of modern medicine say about the $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year decision rule? Medical care. 2008;46(4):349–356. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815c31a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.CDC. [accessed 12 June 2013];HIV Cost Effectiveness. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/preventionprograms/ce/index.htm.

- 60.WHO. [accessed 2013 12 June];Choosing Interventions that are Cost Effective (WHO-CHOICE) http://www.who.int/choice/costs/CER_thresholds/en/

- 61.Wheeler T, Kiran U, Dallabetta G, et al. Learning about scale, measurement and community mobilisation: reflections on the implementation of the Avahan HIV/AIDS initiative in India. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2012;66:ii16–ii25. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Narayanan P, Moulasha K, Wheeler T, et al. Monitoring community mobilisation and organisational capacity among high-risk groups in a large-scale HIV prevention programme in India: selected findings using a Community Ownership and Preparedness Index. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2012;66:ii34–ii41. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeffreys E, Autonomy A, Green J, Vega C. Listen to sex workers: Support decriminalisation and anti-discrimination protections. Interface. 2011;3(2):271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karnataka Health Promotion Trust. Community Mobilization Of Female Sex Workers: Module 2 A Strategic Approach to Empower Female Sex Workers in Karnataka. Bangalore: [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ditmore MH, Allman D. An analysis of the implementation of PEPFAR’s anti-prostitution pledge and its implications for successful HIV prevention among organizations working with sex workers. 2013 doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pathfinder International Advocacy Programs. Fact Sheet, The Anti-Prostitution Loyalty Oath: Undermining HIV/AIDS Prevention and U.S. Foreign Policy. 2006 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cornish F, Campbell C, Shukla A, Banerji R. From brothel to boardroom: Prospects for community leadership of HIV interventions in the context of global funding practices. Health & Place. 2012;18(3):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Global Commission on HIV and the Law. [accessed February 9 2014];HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights and Health. 2012 http://www.hivlawcommission.org/index.php/report.

- 69.NSWP. [accessed February 9 2014];Global consensus statement on sex work, human rights, and the law. 2013 http://www.nswp.org/resource/consensus-statement-english-full.

- 70.Human Rights Watch. [accessed February 9 2014];Sex workers at risk: condoms as evidence of prostitution in four US cities. 2012 http://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/07/19/sex-workers-risk-0.

- 71.WHO, UNFPA, UNAIDS Secretariat et al. Sex Work and HIV Implementation Tool. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wurth MH, Schleifer R, McLemore M, Todrys KW, Amon J. Condoms as evidence of prostitution in the United States and the criminalization of sex work. 2013 doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Conecta Project. Strengthening of HIV/STI interventions in sex work in Ukraine and in the Russian Federation Briefing Paper: Regarding criminalization of sex work, violence, and HIV. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pimenta C, Correa S, Maksud I, Deminicis S, Olivar J. Sexuality and development: Brazilian national response to HIV/AIDS amongst sex workers. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Argento E, Reza-Paul S, Lorway R, et al. Confronting structural violence in sex work: lessons from a community-led HIV prevention project in Mysore, India. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):69–74. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coalition TGSW. Presentation [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biradavolu MR, Burris S, George A, Jena A, Blankenship KM. Can sex workers regulate police? Learning from an HIV prevention project for sex workers in southern India. Social science & medicine. 2009;68(8):1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blankenship KM, Biradavolu MR, Jena A, George A. Challenging the stigmatization of female sex workers through a community-led structural intervention: Learning from a case study of a female sex worker intervention in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 2010. 22(SUPPL. 2):1629–1636. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.516342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klein CH. From One ‘Battle’ to Another: The Making of a Travesti Political Movement in a Brazilian City. Sexualities. 1998;1(3):327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Red Ribbon Award. [accessed April 10, 2013];Asociation de Mujeres Meretrices de la Argentina -Argentina. 2013 http://www.redribbonaward.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=338%3Aammar-argentina&catid=56&Itemid=116&lang=en#.UWWEwDeRdFc.

- 81.Aoxamub N, Zapata T, Sarita S, et al. 5th Africa Conference on Sexual Health & Rights. Windhoek, Namibia: 2012. Empowering sex workers to claim their right to access non-stigmatizing HIV and AIDS, health and social services in Namibia. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arnott J, Crago AL. Rights Not Rescue: A report on female, male, and trans sex worker’s human rights in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa: Open Society Institute. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The Power to Tackle Violence: Avahan’s Experience with Community Led Crisis Response in India. New Delhi, India: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Misra G, Mahal A, Shah R. Protecting the Rights of Sex Workers: The Indian Experience. Health and human rights. 2000;5(1):89–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee. [accessed April 11, 2013];Micro Credit Activities. http://durbar.org/html/micro_credit.asp.

- 86.INDOORS. Capacity building and awareness raising: A European guide with strategies for the empowerment of sex workers. Marseille, France: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 87.The Synergy Project. Room for change: Preventing HIV transmission in brothels: Center for Health Education and Research. University of Washington; [Google Scholar]