Abstract

Patient: Male, 67-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Acute cardiac injury • COVID-19 • pulmonary embolism • stroke

Symptoms: Confusion • diarrhea • dysarthria • fever • myalgia • sore throat

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Mechanical ventilation

Specialty: Critical Care Medicine

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the viral pathogen responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a pandemic respiratory illness. While many patients experience mild to moderate symptoms, severely affected patients often progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Specific to COVID-19, abnormal coagulability appears to be a principal instigator in the progression of disease severity and mortality. In this report we summarize a case of COVID-19 in which extreme thrombophilia led to patient demise.

Case Report:

A 67-year-old man in New York presented to the hospital 14 days after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 at an outpatient site. His initial presenting symptoms included sore throat, headache, fever, and diarrhea. He was brought in by his wife after developing sudden onset confusion and dysarthria. The patient’s clinical picture, which was unstable on presentation, further deteriorated to involve significant desaturations, generalized seizure activity, and cardiac arrest requiring resuscitation. Upon return to spontaneous circulation, the patient required intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor increases. Comprehensive workup uncovered coagulopathy with multiple thrombotic events involving the brain and lungs as well as radiographic evidence of severe lung disease. In the face of an unfavorable clinical picture, the family opted for comfort care measures.

Conclusions:

In this case report on a 67-year-old-man with COVID-19, we present an account of extreme hypercoagulability that led to multiple thrombotic events eventually resulting in the man’s demise. Abnormal coagulation 14 days from positive testing raises the question of whether outpatients with COVID-19 should be screened for hypercoagulability and treated with prophylactic anticoagulation/antiplatelet agents.

MeSH Keywords: Anticoagulants; Case Reports; COVID-19; Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult; Thrombosis

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus pathogen responsible for the global pandemic, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been gaining notoriety in the medical community for its high infectivity [1] and considerable mortality rate [2]. A hallmark of patient demise with COVID-19 is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a life-threatening lung disease characterized by diffuse intrapulmonary inflammation necessitating intensive care and mechanical ventilation. The pathogenesis of ARDS-associated lung injury typically involves the clinical findings of noncardiac pulmonary edema, diffuse inflammatory cell infiltration, and abnormal coagulation. Coagulopathies, specifically intravascular microthrombi and thrombus formation leading to thromboembolic events, are of particular concern for patients with COVID-19. Based on recent studies, coagulation parameters appear to correlate with disease severity [3,4]. Prognosis appears to be improved when high-risk patients, identified by D-dimer and sepsis-induced coagulopathy score (SIC), are appropriately anticoagulated [5]. The International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidelines recommend considering prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin on all patients admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 [6], while the Anticoagulation Forum issued a clinical guidance document recommending pharmacologic prophylaxis for patients with COVID-19 when hospitalized [7]. To our knowledge, no guidance is available for risk assessment and management of hypercoagulability in the out-patient setting. We present a case of hypercoagulability involving a COVID-19-positive patient that resulted in late thromboembolic events eventually leading to his demise.

Case Report

In early April 2020, a 67-year-old man from upstate New York presented to the hospital after developing sudden onset confusion and dysarthria. Two weeks earlier he tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction testing from a nasopharyngeal swab, after endorsing symptoms of sore throat, headache, fever, body aches, and diarrhea. His initial symptoms had improved until the day of hospital presentation.

The patient had a significant past medical history of hyper-tension and dyslipidemia. On presentation, he was symptomatically hypoxic with an oxygen saturation of 75% on room air. On application of supplemental oxygen, via an Oxymask™ set at 5 L/min, his oxygen saturation improved to 95%. Initial laboratory tests in the emergency department showed lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and borderline lactic acidosis (Table 1). Initial arterial blood gas was concerning for mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis. Pertinent laboratory values are reported in Table 1. Based on the patient’s prothrombin time-international normalized ratio, platelet count, and sequential organ failure assessment score, his SIC score was calculated to be 5.

Table 1.

Selected laboratory values for a patient with COVID-19.

| Laboratory test | Value* |

|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 8300/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 12.4 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 24.80% |

| Platelets | 88,000/µL |

| Absolute lymphocytes | 870 cell/µL |

| Lactic acid | 1.9 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 0.8 mg/dL |

| Albumin | 2.8 g/dL |

| Troponin I | 3.26 ng/mL |

| Troponin T | 0.4 ng/mL |

| D-dimer | 9.22 µg/mL |

| INR | 1.28 |

| NT-proBNP | 8105 pg/mL |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 162 |

INR – international normalized ratio; NT-proBNP – N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PaO2/FiO2 – partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen.

Bold denotes abnormal lab value.

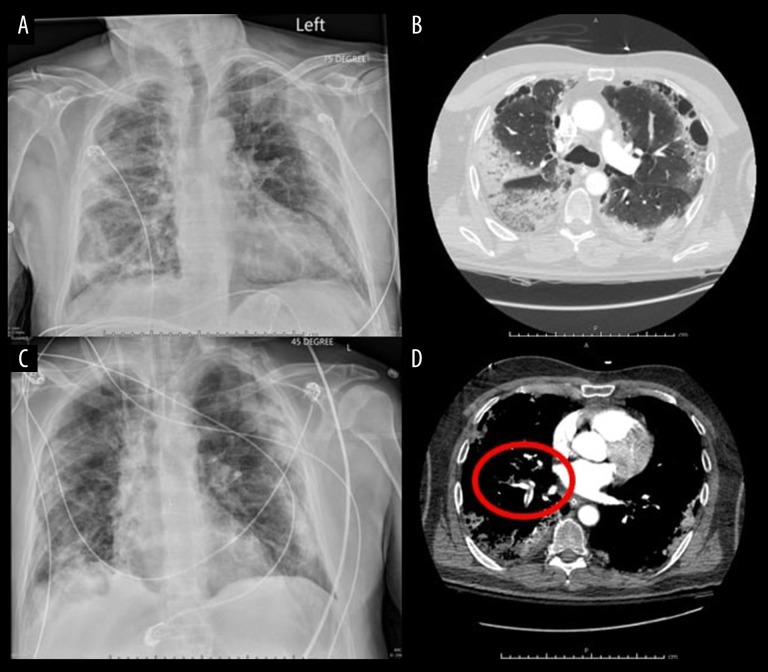

Chest x-ray revealed bilateral airspace opacities in the patient (Figure 1A). His clinical picture quickly declined, resulting in a generalized seizure that spontaneously resolved and cardiac arrest requiring resuscitation. Following return to spontaneous circulation, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where heparin anticoagulation, vasopressors, and mechanical ventilation were initiated. The patient’s ventilator was set to airway-pressure-release-ventilation mode; however, on hospital day 2, due to poor ventilator synchrony, he was switched to pressure-control mode with a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O, FiO2 at 50%, respiratory rate of 8 breaths/min, and inspiratory pressure of 10 cm H2O. Radiographic studies revealed a focal region or wedge-shaped low attenuation in the left temporal region, concerning for acute infarct; diffuse subpleural pneumonitis with regions of ground-glass opacities, consolidation, and paraseptal emphysema (Figure 1B); and acute bilateral pulmonary emboli with evidence of right ventricular dysfunction (Figure 1D). By hospital day 5, it was apparent his prognosis was grim. With increasing vasopressor requirements and oxygen demands in the face of an unchanged chest radiograph (Figure 1C), his family opted for comfort care measures and the patient was terminally extubated.

Figure 1.

Selected imaging studies from a 67-year-old man who presented to the hospital 2 weeks after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2. (A) Chest x-ray on presentation to the hospital; (C) Chest x-ray 5 days after admission to the hospital. (B, D) Computerized tomography angiography scan on presentation to the hospital showing diffuse lung disease (B) and pulmonary artery emboli (red circle) (D).

Discussion

Here we reported a case of COVID-19 that would be classified as mild in the outpatient setting, which was complicated by a late massive thromboembolic phenomenon resulting in eventual patient demise. A combination of chronic illness, immobilization, viral-associated endothelial injury [8], and hyper-coagulability secondary to immune-mediated factors likely precipitated this patient’s thromboembolic events. In the face of the global pandemic, coagulability and thromboembolic events associated with COVID-19 have been persistent observations [6]. Prevention of thrombotic complications should be of utmost concern for public health, but there are few recommendations at this time regarding best practice for assessing risk of thrombosis and thromboprophylaxis in the outpatient setting.

With large-scale community spread of SARS-CoV-2 across the United States, government-mandated stay-at-home orders, and a high frequency of chronic disease in an aging population, it is important to consider the use of prophylactic anticoagulation/antiplatelet agents in the outpatient setting for primary prevention of thrombosis in high-risk individuals with COVID-19 diagnosed in the outpatient setting. Outpatient use of inpatient thrombotic event prediction scores, such as the Padau Prediction Score for risk of venous thromboembolism [9] should be considered, and outpatient blood work (i.e., D-dimer, prothrombin time, complete blood count) may be necessary to identify people at higher risk for thrombotic complications.

To our knowledge, there is only one identifiable clinical trial on the early use of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid in patients with COVID-19 in the outpatient setting [10], and none regarding prophylactic anticoagulant use. While the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidelines recommend considering prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin on all patients admitted to the hospital with COVID-19, the recommendations for outpatients are less well defined. Our case report demonstrates that outpatients with mild COVID-19 can develop life-threatening complications related to thromboembolism. In summary, it is important to further investigate the role of prophylactic anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents in outpatients with COVID-19, and further studies are required to identify the at-risk population.

Conclusions

Our case report demonstrates that life-threatening thromboembolism can occur in outpatients with mild COVID-19. It is important to identify the high-risk patient population, and further studies are needed to investigate the role of prophylactic anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents for COVID-19-positive patients in the outpatient setting.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region – case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–47. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han H, Yang L, Liu R, et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1116–20. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–99. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–26. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva RL. Viral-associated thrombotic microangiopathies. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2011;4(2):51–59. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xijing Hospital Protective effect of aspirin on COVID-19 patients (PEAC) ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04365309.