Abstract

A 23-year old male with bilateral hip dislocations and associated femur head fractures (Pipkin type-II) presented with pain and flexion deformity of both hips after 9 days. After imaging, closed reduction was attempted but failed. Open reduction through Kocher-Langenbeck approach was performed and the femoral head fracture was accessed through Ganz’s safe surgical dislocation. The fracture was reduced anatomically and fixed with headless Herbert screws. After two years, the patient was walking without pain or limp and there was no evidence of osteonecrosis. Simultaneous sequential Ganz’s safe surgical dislocation can be performed in bilateral Pipkin’s fracture dislocation with excellent short term outcome.

Keywords: Pipkin’s fracture dislocation, Ganz’s safe surgical hip dislocation, Femur head fracture, Hip dislocation, Hip preservation

1. Introduction

Traumatic hip dislocation accounts for only 2–5% of all dislocations.1 The association of femoral head fractures with hip dislocations has been reported to range from 4 to 17%.2 Although uncommon, the increase in road traffic accident and improved resuscitative measures has resulted in a growing number of these fractures.3 A bilateral symmetrical hip dislocation with femur head fracture is extremely rare and there are only six case reports in English literature.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 We report a case of bilateral femoral head fracture with posterior hip dislocation in a 23-years young male. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of bilateral Pipkin type II fracture dislocation managed surgically using Trochanteric-flip osteotomy. Consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

2. Case presentation

A 23-year old man presented to us on 9th day of injury with severe bilateral hip pain. He was not able to stand or walk and both the hips were in flexion attitude (Fig. 1). Initial treatment was provided by the local doctor when he was taken to the hospital immediately after a high velocity road traffic accident. He was managed for his head and chest trauma but the hip injury was missed. On examination in our clinic we observed bilateral flexion of the hips with severely painful movement. The attitudes of the limbs were flexion, adduction and internal rotation. There were posterior bulges on both sides with clinical suspicion of posterior dislocation of hips. There was no evidence of distal neurovascular deficit.

Fig. 1.

Flexion deformity of both hips at presentation.

Radiograph of the pelvis showed bilateral posterior hip dislocations with femoral head fractures (Pipkin type II, Fig. 2). Computed tomographic scan with 3D reconstruction confirmed the diagnosis of Pipkin type II fracture dislocation (Fig. 3). Two attempts of closed reduction of the dislocated hip under general anaesthesia failed on both sides, and hence an open reduction was planned. The right side hip was operated first followed by the left side in same setting. One dose of Tranexamic acid (1 gm) was infused along with one course of antibiotic (Cefuroxime 1.5 gm IV) during induction. The patient was positioned on his lateral side and the hip joint was reduced through Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The femoral head fragment was accessed through the trochanteric-flip osteotomy and safe surgical dislocation of the hip.10 While the leg was internally rotated, the posterior border of gluteus medius tendon was identified and then the trochanteric osteotomy of 1.5 cm thickness was performed using an oscillating saw up to the posterior border of vastus lateralis ridge. The osteotomized greater trochanteric fragment was mobilized anteriorly. The anterior capsule was incised along the femoral neck in a Z-shaped fashion where the medial upward capsular incision was made parallel to the acetabular rim extending posteriorly and the lateral inferior capsular incision was extended up to the anterior border of the lesser trochanter. The hip joint was dislocated anteriorly by flexion and external rotation manoeuvre of the limb. The femoral head fragment was extracted out after cutting the ligamentum teres. The hip joint lavage was performed to clean the debris. The fracture site was cleaned and the femoral head was drilled with 2 mm k-wire to look for bleeding. However there was no active pulsatile bleeding. Despite the possibility of osteonecrosis, the broken femoral head fragment was fixed to the femoral head with two headless Herbert screws (Fig. 4). The anterior capsule was repaired and the osteotomy site was fixed with two fully threaded 4.5-mm cortical screws. Reduction and joint congruity was confirmed by C-arm. The patient was turned to the opposite side and the same procedure was repeated. The operative time was 3hrs with blood loss of 400 ml. Postoperative radiograph was satisfactory showing anatomical reduction and rigid fixation (Fig. 5). The patient was advised strict bed rest for six weeks with regular isometric quadriceps exercises and ankle pump. The hip range of movements was started as tolerated by the patient in first postoperative week. He was advised Indomethacin 25 mg TID for six weeks to prevent heterotopic ossification. He started walking with the help of walker after 6 weeks. At the end of 3 months, the fracture united completely and he was mobilized independently. The patient resumed his normal daily activities gradually. He was followed-up at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months and 24 months (Fig. 6). There was no limp or pain and clinical evaluation using Harris hip score revealed a score of 92. Radiographs and Magnetic resonance imaging did not reveal any evidence of osteonecrosis in the hips (Fig. 7).

Fig. 2.

Radiograph of pelvis with both hips shows posterior dislocations with femoral head fractures (Pipkin type II).

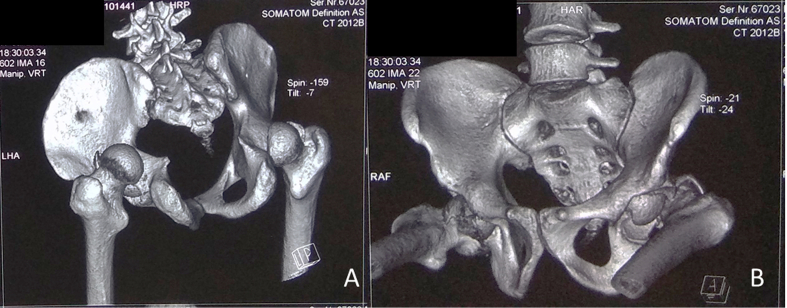

Fig. 3.

3D Reconstruction of Computed Tomographic scan show bilateral posterior hip dislocation with large femoral head fragments inside the joint.

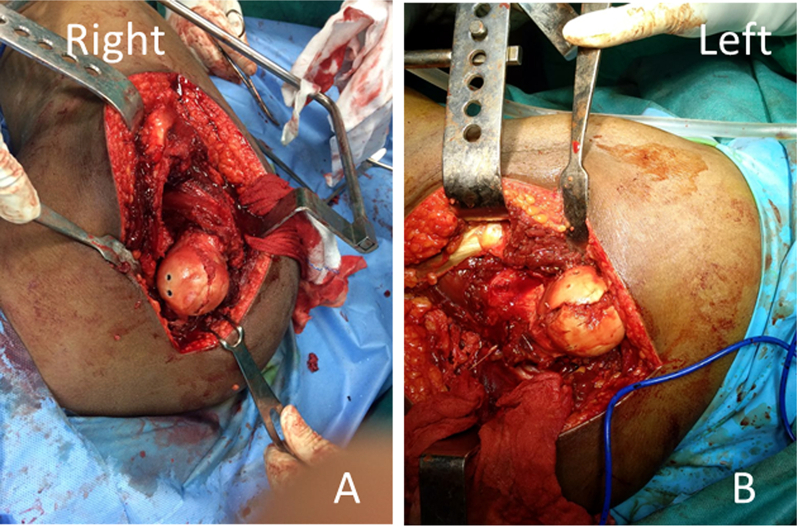

Fig. 4.

The fracture on both sides were reduced and fixed with headless Herbert screws through Ganz’s Trochanteric flip osteotomy.

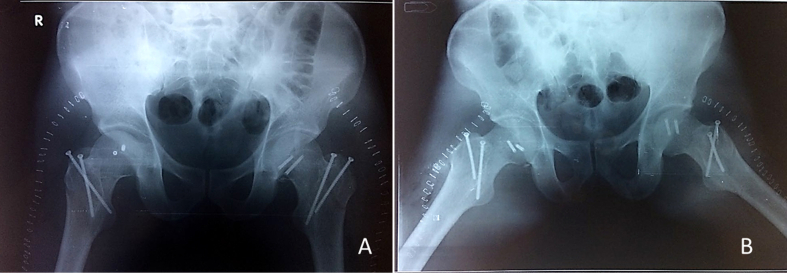

Fig. 5.

Postoperative radiograph shows anatomical reduction of the fracture with congruous joints.

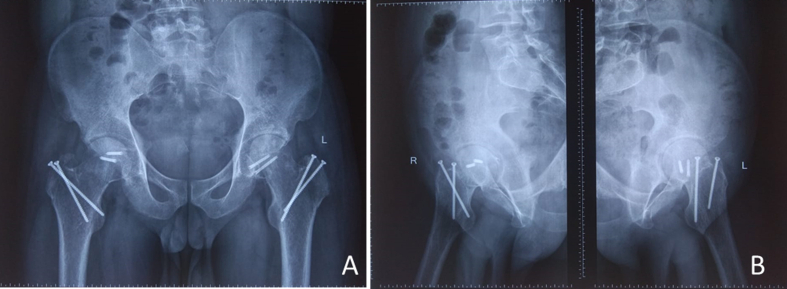

Fig. 6.

Follow-up radiograph at 24-month shows completely healed fracture without any evidence of osteonecrosis.

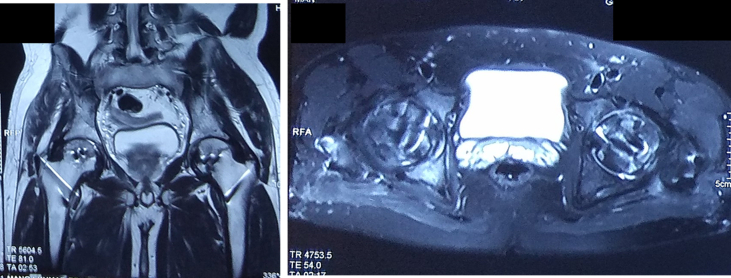

Fig. 7.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows maintenance of joint surface with heterogeneous signals (both hypo and hyper intense T1W and T2W signals in sagittal and axial cut sections) around hardware. There is no evidence of osteonecrosis; signal changes because of metal artefact noted.

3. Discussion

The incidence of bilateral hip dislocation is only 1.25% of all hip dislocations.1 Associated femoral head fracture in such bilateral hip dislocations is extremely rare.1, 2, 3 Such injury usually occurs in dashboard injuries when a dual force is exerted on both the lower limbs with a combination of shear force on the posterior acetabular wall and axial vectoral force along the femoral shaft leading to an avulsion fracture of the femoral head by the pull of ligamentum teres.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The associated head, chest or abdominal injuries in such high velocity trauma usually need urgent attention causing a delay in diagnosis of hip dislocation. This is the reason algorithms have been developed when evaluating and treating patients who have sustained high energy trauma. An anterior-posterior pelvis radiograph must be obtained in every patient who sustains high energy trauma.

An early diagnosis of hip dislocation is essential as the chances of osteonecrosis of the hip increases with delayed reduction.11,12 Sahin et al. reported osteonecrosis in 2.9% and 14.8% of patients when the hip was reduced in <12 h and >12 h respectively.13 Brav also noted 1.47% osteonecrosis when the hip was reduced within 12 h and 56.9% osteonecrosis when the hip was reduced after 12 h.14 In a systematic review, Kellam et al. revealed that delay in reduction of dislocation hips after 12 h increases the risk of developing osteonecrosis 5.6 times.15 The cadaveric studies have revealed a compromise of extra-osseous blood especially the common femoral and circumflex arteries; however intraosseous blood flow is maintained because of collateral circulation.16 Early reduction of the hip may restore blood flow and help to prevent ischemia. Hougaard and Thomsen reported that application of skeletal traction and weight-bearing restriction has no impact on final outcomes.17 The management of bilateral femoral head fracture dislocation is challenging and it should be preferably done within 6-h of trauma to avoid osteonecrosis and arthritis. A closed reduction under general anaesthesia is necessary; however in neglected or late cases it may not be possible to achieve the reduction by closed manner.18 Immediate open reduction of the hip should be performed through Kocher-Langenbeck approach.

Pipkin (1957) reported the first case of bilateral Pipkin fracture dislocation where he managed right sided type-II injury with an endoprosthesis and the left-sided type-III injury by open reduction and internal fixation.4 The first reported symmetrical bilateral Pipkin fracture dislocation (Pipkin type IV) in a 63-year male with Paget’s disease was treated with arthroplasty.5 All reported bilateral femoral head fracture dislocations in young trauma victims have been managed with closed reduction; open reduction and internal fixation through the Smith-Petersen approach have been described when the closed manoeuvre have failed.6,7,9 The older patients have been managed with arthroplasty in all studies.4,5,8

Although delayed hip reduction and associated cartilage damage have negative impact on clinical outcome, the surgical approach, accuracy of fracture reduction and fixation method are also crucial in predicting ultimate outcome.2,19 Anterior approach provides good exposure with minimal blood loss and shorter operative time, but there is increased risk of heterotopic ossification. Contrary to it, the posterior approach doesn’t allow access to the anterior fracture fragment because of the interposition of the femoral head.2,19, 20, 21 With the Trochanteric flip osteotomy and anterior hip dislocation, there is adequate exposure and access to all the parts of femoral head and acetabular rim for fixation.21,22 It is considered as a safe approach having all the advantages of anterior approach with minimal risk of heterotopic ossification because of less retraction or damage to the abductor muscles.

Despite a late presentation (>8 days) and no bleeding from the fracture surface, we attempted a hip preservation procedure as the functional demand of the patient couldn’t have been fulfilled with an artificial hip. Although it is difficult to predict the long-term outcome of this patient, we acknowledge that he has excellent short-term clinical and radiological outcomes without evidence of osteonecrosis. Probably, avoidance of traction, safe surgical dislocation and anatomical reduction are the keys for the success in our case.

4. Conclusion

Symmetrical bilateral femoral head fracture dislocations is an unusual pattern of injury following high velocity trauma. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can decrease the morbidities. Trochanteric osteotomy for safe surgical dislocation of the hip in bilateral femoral head fracture can provide excellent short-term outcome by allowing good access to the fracture fragments and preserving the vascularity of the head.

Informed consent statement

Obtained.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Phillips A.M., Konchwalla A. The pathologic features and mechanism of traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;377:7–10. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kloen P., Siebenrock K.A., Raaymakers E.L.F.B., Marti R.K., Ganz R. Femoral head fractures revisited. Eur J Trauma. 2002;28:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen R.K., Tripathy S.K. Femoral head fracture. In: Goel S.C., editor. ECAB Difficult Hip Fracture. Elsevier Health Sciences; New Delhi: 2014. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pipkin G. Treatment of grade IV fracture-dislocation of the hip. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1957;39:1027–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meislin R.J., Zuckerman J.D. Bilateral posterior hip dislocations with femoral head fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3(4):358–361. doi: 10.1097/00005131-198912000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treacy R.B., Grigoris P.H. Bilateral Pipkin type I fractures. Injury. 1992;23(6):415–416. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(92)90021-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guiral J., Jerez J., Oliart S. Bilateral Pipkin type II fracture of the femoral head. Injury. 1992;23(6):417–418. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(92)90022-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozin S.H., Kolessar D.J., Guanche C.A., Marmar E.C. Bilateral femoral head fracture with posterior hip dislocation. Orthop Rev. 1994:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres L., Coufal C., Pearse M.F., Morandi M. Bilateral Pipkin type II fractures of the femoral head. Orthopedics. 2000;23(7):729–730. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000701-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz R., Gill T.J., Gautier E., Ganz K., Krügel N., Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1119–1124. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b8.11964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannoudis P.V., Kontakis G., Christoforakis Z., Akula M., Tosounidis T., Koutras C. Management, complications and clinical results of femoral head fractures. Injury. 2009;40(12):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonetti J., Ruatti S., Lafontan V. Is femoral head fracture-dislocation management improvable: a retrospective study in 110 cases? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(6):623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahin V., Karakasş E.S., Aksu S., Atlihan D., Turk C.Y., Halici M. Traumatic dislocation and fracture dislocation of the hip: a long-term follow-up study. J Trauma. 2003;54:520–529. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000020394.32496.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brav E.A. Traumatic dislocation of the hip. Army experience and results over a twelve-year period. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1962;44:1115–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellam P., Ostrum R.F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of avascular necrosis and posttraumatic arthritis after traumatic hip dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(1):10–16. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yue J.J., Wilber J.H., Lipuma J.P. Posterior hip dislocations: a cadaveric angiographic study. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:447–454. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hougaard K., Thomsen P.B. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip-prognostic factors influencing the incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1986;106:32–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00435649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park K.H., Kim J.W., Oh C.W., Kim J.W., Oh J.K., Kyung H.S. A treatment strategy to avoid iatrogenic Pipkin type III femoral head fracture-dislocations. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(8):1107–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stannard J.P., Harris H.W., Volgas D.A., Alonso J.E. Functional outcome of patients with femoral head fractures associated with hip dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;377:44–56. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swiontkowski M.F., Thorpe M., Seiler J.G., Hansen S.T. Operative management of displaced femoral head fractures: case-matched comparison of anterior versus posterior approaches for Pipkin I and Pipkin II fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1992;6(4):437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo J.J., Tang N., Yang H.L., Qin L., Leung K.S. Impact of surgical approach on postoperative heterotopic ossification and avascular necrosis in femoral head fractures: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2010;34(3):319–322. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavaskar A.S., Tummala N.C. Ganz surgical dislocation of the hip is a safe technique for operative treatment of Pipkin fractures. Results of a prospective trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(12):544–548. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]