Abstract

Objectives

Accurate diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA) is the first important step in ensuring appropriate management of the disease. A multitude of tests involving assessment of biomarkers help in assessment of severity and grading of osteoarthritic damage. However, most tests are time consuming and are limited by the paucity in synovial fluid volume. In majority of OA effusions, calcium containing crystals are found. The aim of our study was to evaluate whether a correlation existed between the amount of calcium containing crystals present in synovial fluid and severity scoring of OA to propose a quick and inexpensive technique for disease assessment.

Materials and methods

Monosodium-iodoacetate was used to induce high- and low-grade knee OA in adult New Zealand white rabbits (n = 6 joint each group). At 16 weeks, synovial fluid and joints were harvested for histopathological analysis. OA grading was established based on OARSI scoring. Synovial fluid calcium crystal count was assessed by light microscopy (Alizarin red) and confirmed by Fluo-4, AM imaging and polarized microscopy. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student t-test and Pearson correlation.

Results and conclusion

The clumps counted in low-grade OA were significantly lower than high-grade OA, in addition to showing a positive correlation (coefficient: 0.65; P=0.021) between calcium crystal count and the grade of OA created. Fluo-4, AM staining, and polarized microscopy were indicative of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals. This is the first study to suggest that Alizarin red could serve as an effective and rapid, bed-side method for screening and assessing disease progression.

Keywords: Calcium containing crystals, Alizarin red, Synovial fluid, Osteoarthritis

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the leading disabling conditions globally and its accurate diagnosis is essential for managing the disease appropriately.1 Early diagnosis still proves to be challenging as extensive joint degeneration is likely to have occurred before signs and symptoms begin to appear.2 Several biochemical markers of OA have been identified over the past few years, which include new methodologies such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics etc. which are promising yet complex to reproduce.3, 4, 5 Another obstacle in the way of diagnosis is the amount of synovial fluid required for analysis.6

In majority of osteoarthritic effusions, either basic calcium phosphate crystals (BCP) or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals or a combination of both can be found.7 Assessment of calcium containing crystals in synovial fluid is routinely performed by light microscopy using specific stains such as Alizarin red stain, Von Kossa, DiffQuik, Gram stain etc.8,9 Other methods using polarized microscopy and Fluo-4, AM staining for fluorescent imaging of calcium crystals in synovial fluid have also been described as simple and rapid diagnostic tools for identification of crystals containing calcium.10

Creation of OA in an animal model by chemical induction can be achieved by various agents and the present study included the use of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA), an inhibitor of aerobic glycolysis to create dose dependent degeneration of cartilage.11,12

As early diagnosis of OA is paramount and can affect quality of life considerably, our objectives were to successfully create low and high-grade OA using two different concentrations of MIA, followed by assessment of synovial fluid for calcium containing crystals using Alizarin red stain on a wet mount preparation. This was further validated by Fluo-4, AM immunofluorescence staining and polarized microscopy. The aim of this study was to find whether a correlation existed between the amount of calcium containing crystals as seen in the synovial fluid and the severity scoring of OA; to assess the possibility of using crystal count as a potential screening tool for early diagnosis of OA.

2. Materials and methods

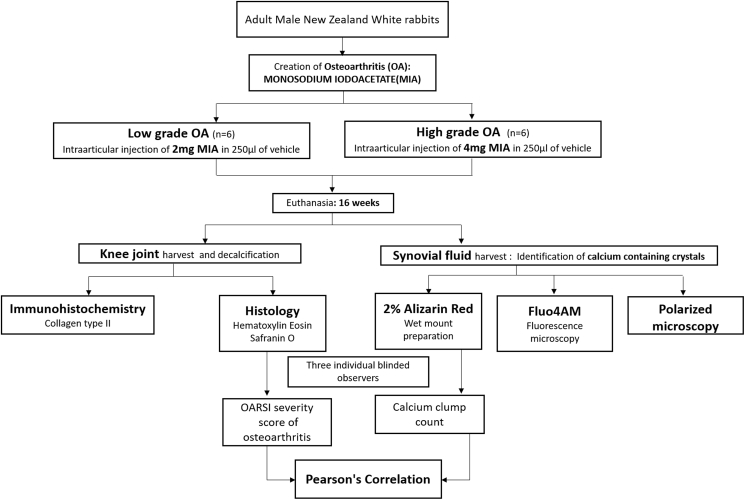

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC). The procedures were in accordance with the institutional guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals. After veterinarian clearance certificate, healthy male New Zealand White rabbits with an average weight of 2.3 ± 0.4 kg were recruited for the study from Geniron Biolabs Pvt Ltd, Anekal, Bangalore and housed at our Institutional Animal House Facility. After two weeks of quarantine, rabbits were assigned a unique identification number, randomized into study groups and maintained in the animal house facility during/following any intervention. The rabbits were anaesthetized using intramuscular injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and 2% xylazine (4 mg/kg). Under sterile aseptic precautions, a single intra-articular injection of MIA reconstituted in sterile water/normal saline was injected into the knee joints. A concentration of 4 mg MIA in 250 μl of the vehicle was injected to create high grade of OA (n = 6 joints) and 2 mg in 250 μl was used for creation of low-grade OA (n = 6 joints). Post-operative care included dosed analgesia, mobility and feed ad libitum (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study algorithm depicting creation of low- and high-grade OA using monosodium iodoacetate, joint and synovial fluid harvest and subsequent evaluation parameters.

2.1. Histopathological analysis

Rabbits were euthanized at the end of 16 weeks and the femoral condyles from the joints with intact articular cartilage were harvested for histological assessment. They were fixed using 10% neutral buffered formalin, followed by decalcification with 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution by constant agitation for over a period of forty days. This was followed by paraffin embedding and sectioning into 5 μm sized slices which were processed for H&E, and Safranin O staining. OA severity scoring was performed based OA Research Society International (OARSI) guidelines by three independent blinded investigators. It is composed of a grading and a staging component, based on histologic features of osteoarthritic progression.13,14 A higher grade indicates a more aggressive biologic progression and a higher stage indicates a wider disease extent. Slides were also processed for immunohistochemical analysis of type II collagen as per protocol prescribed by Amirtham et al.15 In brief, joints were decalcified using 10% EDTA for 40 days under continuous agitation with a change in solution every three days. Following this, the joints were paraffin fixed, sectioned and subjected to antigen retrieval. Slides were treated with 1 mg/ml pronase reagent (Roche), 5 mg/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min each.

Following endogenous and protein block the slides were treated with primary type II collagen antibody at a concentration of 5 μg/ml (mouse monoclonal antibody; DSHB II-II6B3) for overnight incubation at 4 °C. This was followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin for 30 min (Pierce 31430; 1:100 dilution), staining with 3,3-diaminobenzidine solution (DAB; Sigma) and counterstaining with Haematoxylin (Sigma).

2.2. Aspiration of synovial fluid

For collection of synovial fluid, 250 μl of normal saline was injected intra-articularly, and the joint was flexed and extended multiple times to ensure mixing of saline and synovial fluid, following which synovium was incised, and the aspirate was pipetted into vials and cryopreserved.

2.3. Preparation of Alizarin red S stain

2% solution of Alizarin red S solution was prepared, and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 4.2 (addition of ammonium hydroxide). Working solution was filtered using Macherey-Nagel filter paper (615A) thrice and stored away from direct light till further use.

2.4. Wet mount preparation and staining technique

Synovial fluid samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min to ensure that the crystals settled, and the lower most fraction was taken for further evaluation. 5 μL of synovial fluid was mixed with an equal volume of 2% Alizarin red S solution and was used to for the wet mount preparation. Count was performed under low field light microscope (4x) within 3 min of mounting. Crystals were measured based on the number of heavy orange red clumps seen in ten low-power fields counted as per battlement technique. Counts were performed by three independent blinded observers. A negative result was taken as the absence of orange red clumps.

2.5. Fluo-4, AM staining for fluorescence microscopy

Fluo-4, AM, a calcium sensitive dye was also used to confirm the presence of calcium containing crystals in the synovial fluid samples. 5 μl of synovial fluid was incubated with 4 μm Fluo-4, AM (1 mM solution in DMSO, Molecular Probes, Life technologies, Catalogue number F14127), in Tyrode’s solution containing (in mmol/L) NaCl 143, KCl 5.4, Na2H2PO4 0.3, MgCl2 0.5, glucose 5.5, HEPES 5, pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH. In brief, the sample was incubated with Fluo-4, AM in dark for an hour at 37 °C and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 3 min. Supernatant was carefully removed and re-suspended in 100 μl fresh Tyrode’s solution. Sample was then transferred to a clean Petri dish for imaging under fluorescent microscope (Leica DMI 6000B, Excitation at 488, Emission at 514). Bright green fluorescence indicated the presence of calcium containing crystals.

2.6. Polarized microscopy

A wet mount of the synovial fluid was prepared and screened for crystals under polarized light microscopy (Leica DM2000 LED) with polariser and compensator. The crystals were identified based on their shape, polarising and birefringence properties. Positively birefringent crystals appear blue when aligned parallel with the slow axis of the compensator and yellow when perpendicular, whereas the opposite stands true for negatively birefringent crystals.

3. Statistical analysis

Unpaired t-test was used to compare the data between low-grade and high-grade osteoarthritic groups (comparison of severity scoring and calcium clump count). The correlation between the histopathological scoring and the number of calcium containing crystal clumps counted by Alizarin red uptake was performed using Pearson’s correlation. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Microsoft Excel was used for data representation. Statistical Package for Social Scientist (SPSS) version 21.0 software was used for statistical analysis.

4. Results

The mean OARSI score for low grade OA joints was 1.00 ± 0, which was significantly lower than the high-grade group where the score obtained was seen to be 15.17 ± 1.6 (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). This was also evident on histology where high grade OA sections exhibited the presence of surface discontinuity with vertical fissuring, higher degree of cationic (Safranin O) stain depletion into the lower 2/3rd of cartilage, along with comparative reduction in chondrocyte number and loss of cartilage matrix. In the low-grade OA group, histological findings included intact surface with decrease cell number and presence of clustering accompanied by minimal cationic stain depletion. The number of calcium containing crystal clumps counted in the low-grade OA group was 4.83 ± 1.47. This was seen to be significantly lower than the clump count in high-grade group which was 18.83 ± 11.62 (P= 0.031, Fig. 3). Analyses also demonstrated that there was a significant positive correlation between the amount of Alizarin red uptake by the calcium crystals and the severity score assessed based on OARSI scores (r=0.65, P=0.021). The presence of calcium containing crystals in the synovial fluid was also confirmed using Fluo-4, AM imaging, which showed a higher uptake in high grade OA as compared to low grade (Fig. 3). Further validation of crystal type was achieved by polarized microscopy which showed presence of weakly positively birefringent irregularly rhomboid crystals suggestive of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (Fig. 4). For the duration of the study, no adverse events were noted in any animal used for the purpose of the study.

Fig. 2.

Safranin O staining of articular cartilage of rabbit knee joint (A and B) and Immunohistochemical staining of osteochondral sections for collagen type II (C and D)

Bar diagram showing severity score (mean ± SD) as per Osteoarthritis Research Society International grading and staging of the high-grade OA and low-grade OA models created (unpaired t-test, p < 0.001). (OA: Osteoarthritis).

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy pictures of orange-red clumps of calcium containing crystals seen on wet mount preparations of Alizarin red S staining of synovial fluid obtained from the high-grade OA (D and E) and low-grade OA (A and B) models created. Magnification 4x (A and D) and 20x (B and E). Fluorescent microscopy pictures of wet mount preparations of Fluo-4AM staining of synovial fluid obtained from the high-grade OA (F) and low-grade OA (C) models created

Bar diagram showing the maximum number of clumps counted on wet mount preparations of Alizarin red S stained synovial fluid (mean ± SD) obtained from the high-grade OA and low-grade OA models created (unpaired t-test, p < 0.05). (OA: Osteoarthritis).

Fig. 4.

CPPD crystals in synovial fluid obtained from the high-grade OA (D, E, F) and low-grade OA (A, B, C) models created, viewed under polarized microscopy. (CPPD: Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate; OA: Osteoarthritis).

5. Discussion

There are reports which demonstrate presence of calcium containing crystals in early as well as late OA, although studies suggest that such crystals are more commonly seen in patients with higher disease severity.16,17 Detection of crystals in synovial fluid may be achieved by means of specific stains, X-ray diffraction, polarized microscopy etc. Employing Alizarin red is reported to be better than other methods like X-ray diffraction and polarized microscopy due to higher sensitivity.18 The choice of stain was also determined after exclusion of other agents such as DiffQuik and Gram stain which have been reported to have drawbacks in terms of difficulty in detection of crystals on wet mount preparations and increased number of false positives and negatives.8,9 Creation of a non-traumatic model of OA by means of MIA is a standardized method which was utilized in the study to create low- and high-grades of OA adhering to OARSI scoring when examined histopathologically.12,13 Examination of synovial fluid from the respective groups showed that the number of calcium containing crystal clumps counted in high-grade OA were significantly higher than those in the low-grade group, demonstrative of a positive correlation between crystal count and the severity of OA. Some earlier studies using Alizarin red for calcium crystal estimation have reported mixed results in terms of weak or no correlation, although the comparison made was to the radiographic grade or radiological joint destruction in degenerative joint disorder.19,20 Considering the shortcomings of radiographic imaging earlier described, we opted to quantify the extent of cartilage degeneration to measure severity. Hence, this is the first study to establish a correlation between Alizarin red positivity and extent of disease severity based on histopathological changes, although the study would stand to be strengthened with a more stringent comparison of Alizarin red uptake in synovial fluid sample obtained, to each grade of OARSI severity score. In order to confirm the presence of calcium crystals and identify the type of crystal present, Fluo-4, AM staining was performed, which was indicative of the presence of CPPD crystals based on morphological characteristics.21 This was re-emphasized on polarized microscopy.22

As discussed, identification of many OA biomarkers involves complex methods which are expensive and may prove to be difficult owing to the need for high sample volume. The amount of sample required for the proposed method is minimal (5 μl) and still affords detection even at an early stage of OA.

6. Conclusion

The significant difference in Alizarin red uptake in different severity grades of OA, enables us to consider these calcium containing crystals as a measurable biomarker for screening and evaluation of disease progression. Staining with Alizarin red gives distinct results even with scanty amount of synovial fluid. Further, positive correlation between the number of clumps counted and osteoarthritic cartilage degeneration along with the fact that the staining technique is simple and easy to reproduce, allows us to consider Alizarin red staining of synovial fluid as a rapid, time efficient and easily accessible diagnostic tool for assessment of disease severity.

Funding

This work was supported by AO Trauma Asia Pacific (Ref: AOTAP 15-24) of the AO Foundation and Centre for Stem Cell Research Core Grant, (A unit of inStem, Bangaluru), Christian Medical College, Vellore, India.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elizabeth Vinod: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Tephilla Epsibha Jefferson: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Soosai Manickam Amirtham: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Neetu Prince: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Tulasi Geevar: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Grace Rebekah: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Boopalan Ramasamy: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Upasana Kachroo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Histology Lab, Centre for Stem Cell Research and Department of Physiology for infrastructural support.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Vinod, Email: elsyclarence@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Tephilla Epsibha Jefferson, Email: philaslke@gmail.com.

Soosai Manickam Amirtham, Email: sooma_a@hotmail.com.

Neetu Prince, Email: drneetuprince@gmail.com.

Tulasi Geevar, Email: tulasigeevar@gmail.com.

Grace Rebekah, Email: gracerebekah@gmail.com.

Boopalan Ramasamy, Email: jpboopy@gmail.com.

Upasana Kachroo, Email: upasana_k@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Murray C.J.L., Vos T., Lozano R. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Lond Engl. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wieland H.A., Michaelis M., Kirschbaum B.J., Rudolphi K.A. Osteoarthritis — an untreatable disease? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrd1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garnero P. Use of biochemical markers to study and follow patients with osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s11926-006-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L.-C., Zhang H.-Y., Shao L. S100A12 levels in synovial fluid may reflect clinical severity in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. Biomark Biochem Indic Expo Response Susceptibility Chem. 2013;18(3):216–220. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2013.766262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watt F.E. Osteoarthritis biomarkers: year in review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(3):312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heilmann H.H., Lindenhayn K., Walther H.U. [Synovial volume of healthy and arthrotic human knee joints] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1996;134(2):144–148. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibilisco P.A., Schumacher H.R., Hollander J.L., Soper K.A. Synovial fluid crystals in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28(5):511–515. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrocelli A., Wong A.L., Swezey R.L. Identification of pathologic synovial fluid crystals on gram stains. J Clin Rheumatol Pract Rep Rheum Musculoskelet Dis. 1998;4(2):103–104. doi: 10.1097/00124743-199804000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvi E., Manganelli S., Catenaccio M. Diff Quik staining method for detection and identification of monosodium urate and calcium pyrophosphate crystals in synovial fluids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(3):194–198. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez-Santana A., Yavorskyy A., Loughran S.T., McCarthy G.M., McMahon G.P. New approaches in the detection of calcium-containing microcrystals in synovial fluid. Bioanalysis. 2011;3(10):1085–1091. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang L., Li L., Geng C. Monosodium iodoacetate induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway involving ROS production and caspase activation in rat chondrocytes in vitro. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2013;31(3):364–369. doi: 10.1002/jor.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinod E., Boopalan P.R.J.V.C., Arumugam S., Sathishkumar S. Creation of monosodium iodoacetate-induced model of osteoarthritis in rabbit knee joint. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(3):312–314. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2004_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritzker K.P.H., Gay S., Jimenez S.A. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(1):13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Custers R.J.H., Creemers L.B., Verbout A.J., van Rijen M.H.P., Dhert W.J.A., Saris D.B.F. Reliability, reproducibility and variability of the traditional histologic/histochemical grading system vs the new OARSI osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology assessment system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(11):1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amirtham S.M., Ozbey O., Kachroo U., Ramasamy B., Vinod E. Optimization of immunohistochemical detection of collagen type II in osteochondral sections by comparing decalcification and antigen retrieval agent combinations. Clin Anat N Y N. August 2019 doi: 10.1002/ca.23441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olmez N., Schumacher H.R. Crystal deposition and osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 1999;1(2):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s11926-999-0006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nalbant S., Martinez J.a.M., Kitumnuaypong T., Clayburne G., Sieck M., Schumacher H.R. Synovial fluid features and their relations to osteoarthritis severity: new findings from sequential studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11(1):50–54. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoji K. [Alizarin red S staining of calcium compound crystals in synovial fluid] Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;67(4):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul H., Reginato A.J., Schumacher H.R. Alizarin red S staining as a screening test to detect calcium compounds in synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(2):191–200. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggelmeijer F., Dijkmans B.A., Macfarlane J.D., Cats A. Alizarin red S staining of synovial fluid in inflammatory joint disorders. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1991;9(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez-Santana A., Yavorskyy A., Loughran S.T., McCarthy G.M., McMahon G.P. New approaches in the detection of calcium-containing microcrystals in synovial fluid. Bioanalysis. 2011;3(10):1085–1091. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieppe P., Swan A. Identification of crystals in synovial fluid. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58(5):261–263. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.5.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]