Abstract

Most patients have a time limited indication for inferior vena cava filtration. When the indication has expired, a retrievable inferior vena cava filter should be removed percutaneously, unless the risks of retrieval outweigh the benefits. Over time, long term indwelling inferior vena cava filters may experience complications, such as strut penetration, migration, thrombosis, tilt, fracture, and inferior vena cava stenosis. Long term indwelling retrievable inferior vena cava filters may become embedded in the wall of the inferior vena cava, making percutaneous retrieval difficult. However, this is not always the case, and they also may be easily and safely removed using simple techniques. We present a case of a long term indwelling retrievable inferior vena cava filter that was easily removed using simple techniques, 16.5 years after placement.

Keywords: Retrievable inferior vena cava filter, Removal IVC filter, IVC filter complications, Gunther-Tulip IVC filter, IVC filter strut penetration

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and usually occurs secondary to venous thromboembolism [1]. The current standard of treatment for venous thromboembolism leading to PE is medical anticoagulation therapy [2]. However, certain patients at risk for developing PE have either a contraindication to anticoagulation (eg, recent hemorrhage, recent surgery), complication of anticoagulation, or experience a failure of anticoagulation. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters are minimally invasive mechanical devices placed into the IVC of patients who cannot be treated with anticoagulation [3]. Because IVC filters have the potential to remain within the body over extended periods of time, complications can occur, such as caval wall penetration, migration, thrombosis, tilt, fracture, and IVC stenosis [4]. These potential complications have stressed recent emphasis of IVC filter removal, especially when the filter is no longer indicated [5]. However, the very complications associated with longer filter dwell times give many providers pause as it relates to removal, despite several advanced techniques for filter removal published in the literature [6], [7], [8].

The longest retrievable Günther-Tulip IVC filter (Cook Medical Corp., Bloomington, IN) has remained in place before percutaneous removal has been 15.5 years [9]. We present a case of an uneventful, successful percutaneous IVC filter removal with a dwell time of 6033 days (16.5 years).

Case report

A 38-year-old man with a past medical history of hypothyroidism presented from an outside hospital in 2003 as a multitrauma following a snowmobile accident. The patient was helmeted when he collided head-on with another snowmobile. The patient suffered subdural and epidural hematomas, a cardiac contusion with MRI evidence of tear and tamponade, lung contusions, a grade IV splenic laceration, bilateral grade II renal lacerations, and multiple comminuted fractures to his left scapula, left wrist and multiple ribs. Neurosurgery recommended conservative management with close clinical follow-up given the size and location of the subdural and epidural hematomas. The patient was taken to interventional radiology (IR) where he underwent successful splenic artery embolization. Because of the setting of multitrauma with an expected protraction of his nonmobile, a Günther-Tulip Vena Cava Filter was also placed for PE prophylaxis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Reformatted average-intensity-projection contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen in the coronal plane demonstrating successful placement of a Gunther-Tulip IVC filter in the infrarenal vena cava in 2003.

The patient recovered from his injuries, other than chronic neuromuscular dysfunction of his left arm, and experienced no venous thromboembolic events. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up, as he temporarily moved to another state, and his IVC filter was not removed.

After 16.5 years, the patient returned to our IR clinic expressing the desire to have the uncomplicated, IVC filter removed. He explained that he no longer wished to have his IVC filter in place, even though he was asymptomatic related to the IVC filter. The patient was counseled regarding the risk of removal of IVC filters with long dwell times, as mentioned in the introduction. The interventional radiologist ultimately made the decision to remove the IVC filter.

Preprocedure CT imaging demonstrated grade 1 to 2 penetrations of the 4 struts through the IVC wall, based on the Oh classification [4]. There was no additional involvement of the penetrated struts with any adjacent structure, nor was there evidence of filter thrombus, tilt, migration, or fracture (Figs. 2A and 2B).

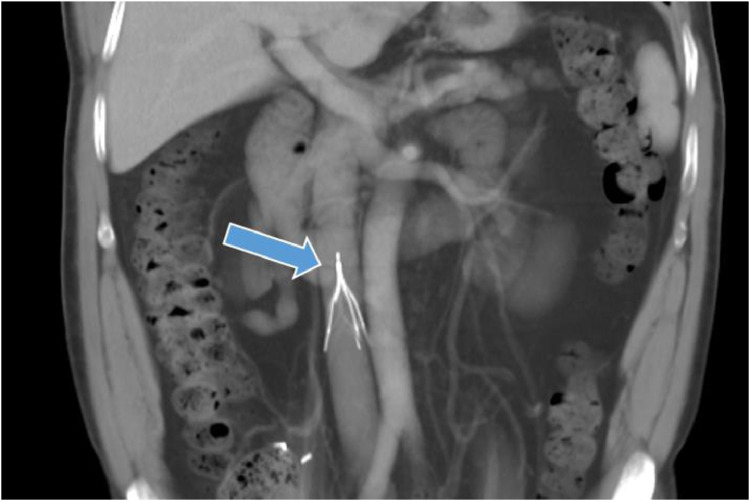

Fig. 2A.

Reformatted average-intensity-projection contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen in the coronal plane from 2018 demonstrating the stable positioning of the well-aligned IVC filter with no evidence of filter thrombus.

Fig. 2B.

Single-slice axial contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery origin demonstrating grade 1 and 2 penetrations of the 4 struts. No interaction of adjacent structures by the struts is seen.

Informed consent was obtained following the explanation of the risks and benefits of the procedure and of moderate sedation. In the IR suite the patient was placed in the supine position. Conscious sedation was achieved with a total of 150 mcg of intravenous fentanyl and 3.5 mg of intravenous midazolam. Local anesthesia was achieved with 1% buffered lidocaine. Initial digital radiographic images demonstrated an intact Günther-Tulip IVC filter (Fig. 3). Via a right internal jugular vein approach, the IVC was accessed and a flush catheter was advanced down into the IVC. An initial inferior venacavogram demonstrated no evidence of IVC thrombus (Fig. 4). Through a 10-French sheath, a nitinol snare device (Amplatz Goose Neck Snare, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) was used to engage the hook of the IVC filter (Fig. 5). The sheath was easily advanced over the IVC filter, collapsing it (Fig. 6). The filter was pulled completely into the sheath and the intact IVC filter was completely removed from the patient. Inspection of the IVC filter demonstrated no fracture or missing components. A final inferior venacavogram demonstrated a normal IVC with no evidence of contrast media extravasation, stenosis, thrombosis, or dissection (Fig. 7). The patient tolerated the procedure well and without procedure-related complication. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, continued to endorse no ill effects from the procedure, and remained in his usual state of health.

Fig. 3.

Initial fluoroscopic scout imaging during filter retrieval demonstrating an intact Günther-Tulip filter.

Fig. 4.

Initial conventional inferior venacavogram demonstrating no evidence of filter thrombus. Note the aforementioned penetration by the struts.

Fig. 5.

Fluoroscopic imaging demonstrating the snare device engaging retrieval hook of the IVC filter.

Fig. 6.

Successful advancement of the 10-French sheath over the IVC filter, collapsing it into the sheath.

Fig. 7.

Final post-IVC filter removal inferior venacavogram demonstrating an intact IVC with no evidence of contrast media extravasation, thrombosis, dissection, or stenosis.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the prospect of uneventful IVC filter removal for filters that have been in place for an extended period of time. A more challenging retrieval was anticipated due to suspected ingrowth of the IVC filter into the IVC wall secondary to endothelialization from a long dwell time. However, the IVC filter was percutaneously removed effortlessly and without complication, using simple technique with a loop snare. Any endothelialization of the IVC filter that was present did not impede retrieval. This case also demonstrates that long dwell times do not necessarily limit the possibility for simple and safe percutaneous removal.

At this time and with the limitations of a single case report, we cannot fully identify and assess factors that predict a straightforward retrieval. However, it is important to note the filter type in this case, a Günther-Tulip IVC filter, does seem to be amenable to percutaneous retrieval using simple techniques after a prolonged dwell time. Another important factor used to assess ease or possibility of retrieval using simple technique was proper evaluation of the IVC filter and patient's anatomy with preprocedure imaging. Though imaging cannot always demonstrate endothelialization or IVC wall ingrowth, known as IVC filter embedding, it can provide other important information, such as filter tilt, which may predispose to embedding of the retrieval hook into the wall of the IVC. Preprocedure imaging will also assess for thrombus in the IVC filter or IVC, strut penetration, or fracture.

This is only a single case study and should not be assumed to represent all cases of long dwell time retrievable IVC filters. However, this does further illustrate the possibility for expeditious and uneventful percutaneous removal. These encouraging findings point to the need of more studies regarding removal of IVC filters with long dwell times in an effort to continue to improve on long-term management of these devices.

References

- 1.Caplin D.M., Nikolicn B., Kalva S.P., Ganguli S., Saad W.E., Zuckerman D.A. et al. (2011). Quality improvement guidelines for the performance of inferior vena cava filter placement for the prevention of pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(11):1499-1506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Raja A.S., Greenberg J.O., Qaseem A., Denberg T.D., Fitterman N., Schuur J.D. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701–711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner T.E., Saeed M.J., Novak E., Brown D.L. Association of inferior vena cava filter placement for venous thromboembolic disease and a contraindication to anticoagulation with 30-day mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh J.C., Trerotola S.O., Dagli M., Shlansky-Goldberg R.D., Soulen M.C., Itkin M. Removal of retrievable inferior vena cava filters with computed tomography findings indicating tenting or penetration of the inferior vena cava wall. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(1):70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albrecht R.M., Garwe T., Carter S.M., Maurer A.J. Retrievable inferior vena cava filters in trauma patients: factors that influence removal rate and an argument for institutional protocols. Am J Surg. 2012;203(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliescu B., Haskal Z.J. Advanced techniques for removal of retrievable inferior vena cava filters. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35(4):741–750. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0205-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Hakim R., Kee S.T., Olinger K., Lee E.W., Moriarty J.M., McWilliams J.P. Inferior vena cava filter retrieval: effectiveness and complications of routine and advanced techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(6):933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hakim R., McWilliams J.P., Derry W., Kee S.T. The hangman technique: a modified loop snare technique for the retrieval of inferior vena cava filters with embedded hooks. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(1):107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodfield C.A., Hall A.M., Kim H.Y. Uncomplicated removal of a Günther-Tulip inferior vena cava filter 15.5 years after placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42(1):160–162. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]