Inclusion bodies (IBs) are cytoplasmic sites of RNA synthesis for a variety of negative-sense RNA viruses, including Ebola virus. In addition to housing important steps in the viral life cycle, IBs protect new viral RNA from innate immune attack and contain specific host proteins whose function is under study. A key viral factor in Ebola virus IB formation is the nucleoprotein, NP, which also is important in RNA encapsidation and synthesis. In this study, we have identified two domains of NP that control inclusion body formation. One of these, the central domain (CD), interacts with viral protein VP35 to control both inclusion body formation and RNA synthesis. The other is the NP C-terminal domain (NP-Ct), whose function has not previously been reported. These findings contribute to a model in which NP and its interactions with VP35 link the establishment of IBs to the synthesis of viral RNA.

KEYWORDS: RNA replication, ebola virus, inclusion body, nucleoprotein

ABSTRACT

Ebola virus (EBOV) inclusion bodies (IBs) are cytoplasmic sites of nucleocapsid formation and RNA replication, housing key steps in the virus life cycle that warrant further investigation. During infection, IBs display dynamic properties regarding their size and location. The contents of IBs also must transition prior to further viral maturation, assembly, and release, implying additional steps in IB function. Interestingly, the expression of the viral nucleoprotein (NP) alone is sufficient for the generation of IBs, indicating that it plays an important role in IB formation during infection. In addition to NP, other components of the nucleocapsid localize to IBs, including VP35, VP24, VP30, and the RNA polymerase L. We previously defined and solved the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of NP (NP-Ct), but its role in virus replication remained unclear. Here, we show that NP-Ct is necessary for IB formation when NP is expressed alone. Interestingly, we find that NP-Ct is also required for the production of infectious virus-like particles (VLPs), and that defective VLPs with NP-Ct deletions are significantly reduced in viral RNA content. Furthermore, coexpression of the nucleocapsid component VP35 overcomes deletion of NP-Ct in triggering IB formation, demonstrating a functional interaction between the two proteins. Of all the EBOV proteins, only VP35 is able to overcome the defect in IB formation caused by the deletion of NP-Ct. This effect is mediated by a novel protein-protein interaction between VP35 and NP that controls both regulation of IB formation and RNA replication itself and that is mediated by a newly identified functional domain of NP, the central domain.

IMPORTANCE Inclusion bodies (IBs) are cytoplasmic sites of RNA synthesis for a variety of negative-sense RNA viruses, including Ebola virus. In addition to housing important steps in the viral life cycle, IBs protect new viral RNA from innate immune attack and contain specific host proteins whose function is under study. A key viral factor in Ebola virus IB formation is the nucleoprotein, NP, which also is important in RNA encapsidation and synthesis. In this study, we have identified two domains of NP that control inclusion body formation. One of these, the central domain (CD), interacts with viral protein VP35 to control both inclusion body formation and RNA synthesis. The other is the NP C-terminal domain (NP-Ct), whose function has not previously been reported. These findings contribute to a model in which NP and its interactions with VP35 link the establishment of IBs to the synthesis of viral RNA.

INTRODUCTION

Ebola virus (EBOV) causes severe, often fatal hemorrhagic disease in humans and is currently receiving enhanced attention due to a recent large outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo during late 2018 to early 2020. Promising vaccination development is underway, but efforts to better understand EBOV virology and pathogenesis so that additional approaches to prophylaxis and therapeutic discovery can be developed are still required (1–4).

Along with EBOV and the related Marburg virus (MARV), several well-characterized negative-strand RNA viruses, including vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rabies virus (RABV), human parainfluenza virus (HPIV), Nipah virus (NiV), and human metapneumovirus (hMPV), carry out key replication steps in specialized cytoplasmic compartments, referred to as inclusions, inclusion bodies (IBs), or Negri bodies (in the case of RABV) (5–19). In general, IBs are complex sites of viral RNA synthesis and contain viral proteins required for this process. In addition, IBs colocalize with specific host proteins whose roles in formation, maintenance, and/or function of IBs are under study (19–25). Typically, IBs lack an organizing outer membrane, and, in some cases, their formation is driven by liquid-phase separation, a physical consequence of specific viral protein properties (26, 27). Evidence from RABV, RSV, and EBOV suggests a dynamic relationship between IBs and virus-induced stress granules or specific stress granule proteins, and that this relationship regulates the innate immune response to infection (20, 23, 28). IBs are also thought to present a physical barrier to protect their RNA contents from innate immune attack. Precisely how IBs come into existence, the exact molecular processes they support during RNA synthesis, how they interfere with innate immunity, and how they pass their contents along for further viral maturation are all incompletely answered questions that have garnered recent scrutiny.

IBs within EBOV-infected cells are initially small and located near the endoplasmic reticulum but become more widespread as infection progresses, and many increase in size (17, 29, 30). They contain viral proteins NP, VP35, VP40, VP30, VP24, and L, which are involved in various aspects of positive- and negative-sense RNA synthesis, nucleocapsid assembly and function, and viral maturation (30–32). Indeed, intact viral nucleocapsids have been visualized within EBOV IBs (18, 29, 33). The nucleoproteins (NP) of EBOV and MARV are key players in initiating IB formation, and cells ectopically expressing NP as the only viral factor contain NP-induced IBs, demonstrating that NP is sufficient for IB formation (10, 29, 34–37). In contrast, other viral nucleocapsid proteins fail to exhibit this behavior when individually expressed (34, 35, 38, 39), although there are somewhat conflicting data regarding the L polymerase in this regard. NP is a multifunctional 739-amino-acid (aa) protein that is the most abundant component of the viral nucleocapsid, and, in addition to triggering IB formation, its roles include RNA packaging, acting as a cofactor for RNA synthesis carried out by the viral polymerase L, and nucleocapsid assembly (32). A second viral protein, VP35, is also a required cofactor for EBOV and MARV RNA synthesis and is important in nucleocapsid function and assembly (40, 41). VP35 associates with NP and L and is found in IBs when coexpressed with NP, and one of its functions is to act as a bridge between NP and L in the formation of productive replication complexes (34, 35, 42). Physical interactions between VP35 and NP have been observed that involve both the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of NP (34, 41, 43–46), and these have been directly implicated in supporting viral RNA synthesis. Recently, VP35 was shown to possess NTPase and helicase-like activities, which are proposed to support RNA remodeling during synthesis (47). VP35 also has well-documented anti-interferon (IFN) activity (48, 49).

Previously, we reported the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of NP (NP-Ct) from EBOV and the corresponding proteins from Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and Bundibugyo virus (BDBV) (50–52). NP-Ct is highly conserved across filoviruses and assumes a novel tertiary fold structure (50–53). Whereas activities carried out by the N-terminal domain of NP (aa 1 to 412; Fig. 1) have been well-characterized and include RNA binding, NP oligomerization, and physical association with VP35 and L, the activities of NP-Ct have remained a mystery. In this report, we demonstrate two novel and redundant functions of NP that control IB formation. One of these is carried out by NP-Ct, which we observe also plays a separate novel role in the production of infectious transcription and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs). The other IB-controlling function of NP is located within a previously uncharacterized region of the protein that spans amino acid positions 481 to 500 and is responsible for binding to the interferon inhibitory domain (IID) of VP35. Importantly, we find this region of NP (the central domain, or CD) to be crucially important not only for IB formation but also for viral RNA synthesis. Together, these findings reveal new activities for NP in several key viral replication steps and add to the complexity of viral RNA synthesis and IB dynamics that may be exploited for small-molecule inhibitor discovery.

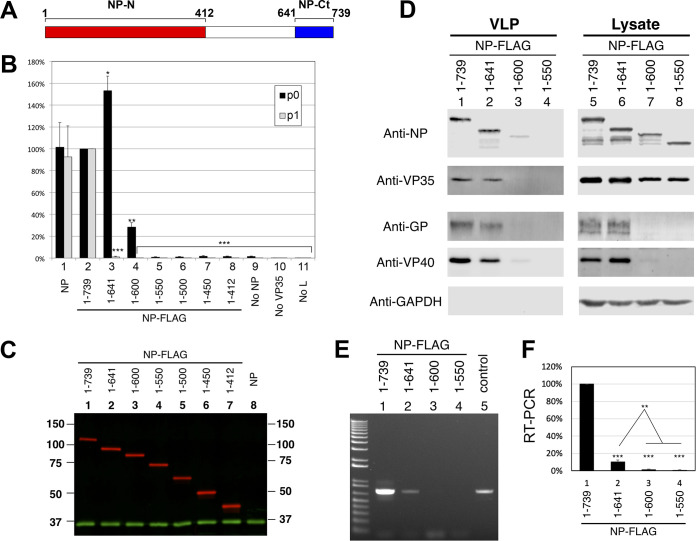

FIG 1.

NP-Ct is required for infectious VLP production. (A) NP primary structure. The precise definition of the N-terminal domain is subject to interpretation based on sequences included in constructs used for structural and biochemical studies (43, 44, 51, 66) but here is labeled aa 1-412 based on sequence conservation. NP-Ct domain definition is based on Dziubańska et al. (51). (B) trVLP assay (p0 cells) of NP deletion mutants. Indicated NP-FLAG constructs were transfected into 293T/17 cells. As described in the text, recipient p1 cells were supplied with wild-type NP. Data are averages from independent biological triplicates. Error bars represent the SD for the triplicates. Marks above the bar indicate P values to the corresponding NP-FLAG samples based on Student’s t tests: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Untagged NP (column 1) showed no statistically significant difference from the corresponding NP-FLAG samples. (C) Western blot of lysates from p0 cell transfectants. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-FLAG (red) or anti-GAPDH (green) antibody. (D) Western blot analysis of purified trVLPs and corresponding lysate from p0 transfectants. Indicated NP-FLAG constructs were transfected into 293T cells (p0) along with all other trVLP components. trVLPs were purified from the supernatant as described in Materials and Methods. trVLPs and corresponding cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Anti-GAPDH was used as a loading control for the lysate samples and as a specificity control for the purified trVLPs. (E) RT-PCR quantification of genomic (negative-strand) RNA from the indicated isolated trVLPs. Isolated RNA was subjected to RT-PCR and quantified using linear range amplification standards as described in Materials and Methods. Positive control indicates a PCR product of a minigenome DNA template. (F) Quantitation of RT-PCR. PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified with the Molecular Imager XRS system. Means and standard deviations from biological triplicate experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate P values based on Student's t test: ***, P < 0.001 to the NP(1-739) sample; **, P < 0.01 between NP(1-641) and NP(1-600) or NP(1-550).

RESULTS

NP-Ct is required for production of infectious VLPs but not for transcription or RNA replication.

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, NP-Ct spans amino acids 641 to 739, which corresponds to a region of high sequence conservation among Ebolavirus species (51). To investigate its function, a series of deletion mutants were tested in the trVLP assay (54–56). In this assay, viral proteins VP40, VP24, and GP are expressed from a tetracistronic minigenome (MG), which also expresses Renilla luciferase as a reporter. All other viral proteins (NP, VP35, VP30, and L) are supplied individually by transfection. The transfected passage 0 (p0) cells are competent for transcription, RNA replication, and production of infectious VLPs containing newly replicated and encapsidated MGs. trVLPs can be recovered from the p0 supernatant and used to infect p1 cells, which will produce new MGs and trVLPs if they also are supplied by transfection with plasmids encoding NP, VP35, VP30, and L. Importantly, we expressed NP deletion mutants in p0 cells but provided wild-type NP in p1 cells, allowing determination of whether p0 cells produced infectious trVLPs whose replication could be supported in p1 cells. Also, in p0 cells the pCAGGS-NP expression plasmid was replaced with a pCAGGS-NP-FLAG construct (and mutant derivatives), which we found to support trVLP activity equal to that of untagged NP (Fig. 1B). Full-length and all mutant NP were expressed at very similar levels, as shown in Fig. 1C.

Deletion of the C-terminal 139 amino acid residues in NP(1-600) reduced reporter activity down to ∼28% of the full-length protein in p0 cells, which is consistent with previous results (36) and is due to the loss of a VP30 binding site (aa 600 to 615/617) that controls RNA synthesis, as described previously (57, 58). Mutant NP(1-550) or mutants with larger C-terminal deletions had less than 2% of wild-type reporter activity in p0 cells, with no statistically significant difference from a control lacking NP altogether, indicating a severe defect in transcription and/or RNA replication. In contrast, precise deletion of NP-Ct in NP(1-641) had no deleterious effect on reporter gene expression in p0 cells, indicating that NP(1-641) fully supports transcription and RNA replication. Strikingly, however, when p0 cell supernatants from cells expressing NP(1-641) were used to infect p1 cells, reporter activity was only 1.0% of that of the wild type, even though the p1 cells expressed wild-type NP supplied by transfection. These data demonstrate that despite wild-type levels of transcription and replication in p0 cells expressing NP(1-641), the p0 supernatants contained virtually no infectious trVLPs. To understand this infectivity defect, trVLPs were isolated from p0 supernatants and analyzed for protein and negative-strand viral RNA content using our previously published methods (56). Interestingly, trVLPs isolated from p0 cells expressing either wild-type NP or NP(1-641) contained equal amounts of NP, indicating that the NP-Ct deletion did not result in a defect in NP incorporation into trVLPs. Furthermore, these trVLPs also contained wild-type levels of VP35, GP, and VP40, demonstrating that they were indeed assembled trVLPs (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 and 2). However, the expression of NP(1-600) or (NP1-550) did not produce intact trVLPs (Fig. 1D, lanes 3 and 4), consistent with the fact that the p0 cells expressing these proteins also did not express GP or VP40 (Fig. 1D, lanes 7 and 8) or efficiently produce infectious VLPs, as shown in Fig. 1B. Importantly, trVLPs containing NP(1-641) contained significantly decreased amounts (10%) of genomic RNA compared with wild-type VLPs, which clearly correlates with their infectivity defect (Fig. 1E and F). This indicates that NP-Ct has an important role in genomic RNA incorporation or stability within the trVLP’s nucleocapsid and, as such, supports our conclusion of a novel function for this domain.

NP-Ct is required for formation of inclusion bodies.

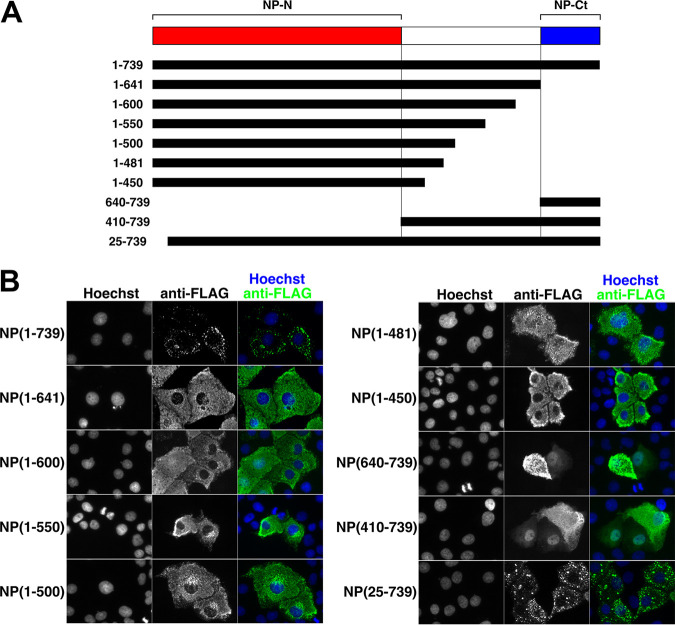

As previously reported, NP from EBOV or MARV forms NP-induced IBs even in the absence of other viral proteins or viral RNA (10, 17, 29, 30, 34). To determine the role of NP-Ct in this process, HuH-7 cells were transfected with various NP-FLAG deletion constructs (Fig. 2A) and stained with an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2B). Full-length NP localized in IBs as expected, but NP(1-641), precisely lacking NP-Ct, was clearly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, and no IBs were observed. All other C-terminal deletion mutants of NP lacking NP-Ct, namely, NP region of aa 1 to 600 (termed region 1-600), 1-550, 1-500, 1-481, and 1-450, also did not localize in IBs (Fig. 2B). The expression of NP-Ct by itself as NP(640-739) was not sufficient for IB formation, and NP(410-739) did not localize to IBs, indicating that additional N-terminal domains are required. Deletion of the N-terminal aa 1 to 24 region, part of which is required for NP oligomerization and virus replication (43, 44), had no effect on IB formation, indicating that this region is dispensable for triggering IB formation. Together, these results demonstrate that NP-Ct is an essential element for NP-induced IB formation.

FIG 2.

NP-Ct is required for IB formation. (A) Structure of NP deletion mutants. Each construct contains a C-terminal FLAG tag. (B) HuH-7 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and stained with anti-FLAG antibody and Hoechst 33342 dye after 48 h. All constructs lacking the NP-Ct failed to localize in IBs.

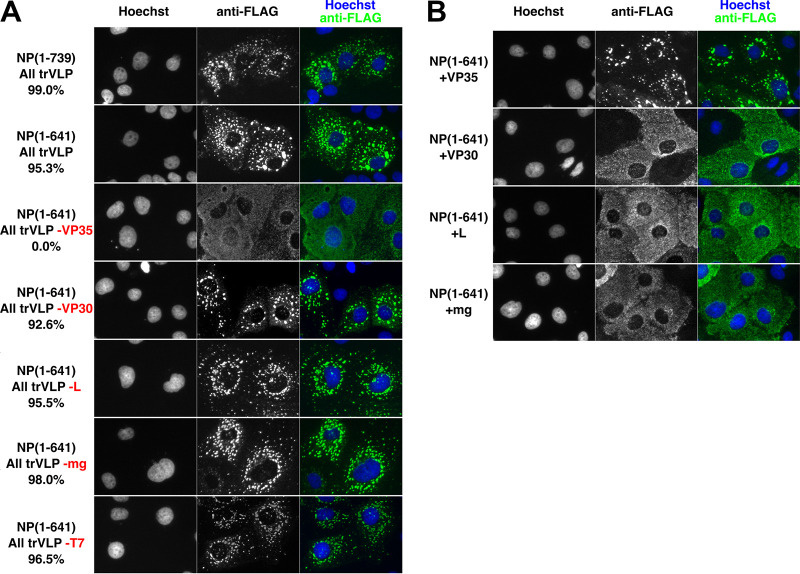

VP35 specifically complements deletion of NP-Ct.

We wondered if the role of NP-Ct in IB formation is linked to its requirement for the production of infectious VLPs, as presented in Fig. 1. Accordingly, we examined the localization of mutant NP(1-641) in the context of cells expressing all other trVLP assay components. Under these conditions, NP(1-641) clearly localized in IBs (Fig. 3A, 2nd row), in complete contrast to its behavior when expressed alone (Fig. 2). This indicated that one or more components of the trVLP system could complement the mislocalization of NP(1-641). We then systematically omitted each of the trVLP expression plasmids to identify which plasmid is necessary for complementing the mislocalization of NP(1-641). As shown in Fig. 3A, only omission of the VP35 expression plasmid, but not of any other trVLP system component, resulted in the mislocalization of NP(1-641). To confirm that VP35 is indeed necessary and sufficient to complement the NP-Ct deletion, each plasmid of the trVLP system was transfected individually along with NP(1-641), as shown in Fig. 3B. The VP35 expression plasmid was the only one that complemented mislocalization of NP(1-641).

FIG 3.

VP35 specifically complements deletion of NP-Ct. (A) FLAG-tagged NP(1-739) or NP(1-641) was transfected along with other trVLP components, i.e., expression plasmids for VP35, VP30, L, T7 polymerase, a tetracistronic minigenome (MG) expressing VP24, GP, and VP40, and firefly luciferase, as indicated, and immunostained with anti-FLAG antibody. Individually omitted constructs are indicated in red. (B) NP(1-641) was cotransfected with each of the indicated individual plasmids of the trVLP system.

To avoid the potential problem of individual transfected cells receiving less than the full complement of plasmids, we used a lipid-based transfection with transfection complexes containing numerous plasmid copies. Given that the molecular weight of the transfected plasmids was between 3.5 × 106 and 7 × 106 g/mol and that there were ∼1 × 106 cells per well at the time of transfection, this means that for each cell there were >10,000 plasmid copies available for transfection of even the smallest amounts (i.e., 75 ng). Thus, if a cell took up a transfection complex, it was very unlikely that plasmids of a single type would be absent from the complex. More importantly, our data clearly show that when we omitted the VP35 plasmid, we observed a dramatic change in phenotype, which we did not observe in any of the other cases (Fig. 3). To confirm the data shown in Fig. 3 indeed represent the typical phenotype of transfected cells, we counted 200+ cells per sample for each biological replicate, comparing NP in the inclusion bodies with overall NP-positive cells. In every case except the sample omitting the VP35 plasmid, the IB phenotype was >90% of stained cells, and in the sample omitting VP35, it was 0%. These results demonstrate that VP35 is necessary and sufficient for NP(1-641) localization to IBs. VP35 is a cofactor for EBOV RNA synthesis and also has anti-interferon (IFN) activity (31). Since VP35 fails to trigger IB formation on its own (10, 34), these data also demonstrate that in the context of NP(1-641) expression, only two proteins, NP and VP35, are sufficient for IB formation. The data also show that mislocalization of NP(1-641) was likely not the cause of failure to produce infectious VLPs in p0 supernatants (Fig. 1), because in cells that included NP(1-641) and all other trVLP components, including VP35, intact IBs were observed with proper NP(1-641) localization. This strongly suggests the presence of dual, separate functions in NP-Ct, one involved in infectious VLP production and the other controlling IB formation.

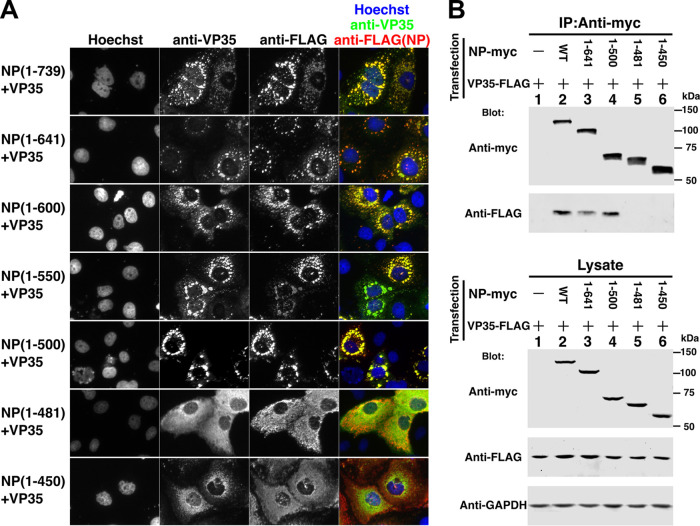

The 481-500 region of NP is required for IB formation and for association with VP35.

Because NP(1-641) localized in IBs when coexpressed with VP35, additional constructs were created to test which NP region is specifically required for IB formation in the presence of VP35, as presented in Fig. 4A. FLAG-tagged C-terminal deletion mutants of NP were cotransfected with VP35. Full-length NP(1-739) as well as all C-terminal deletion mutants up to NP(1-500) colocalized efficiently with VP35 in IBs, but neither NP(1-481) nor NP(1-450) did so. This indicates that the NP 481-500 region is required for IB localization when coexpressed with VP35 and explains the complementing activity of VP35 toward NP(1-641). However, as shown in Fig. 1B, deletion mutants NP(1-550) or further C-terminal deletions showed trVLP activity of less than 1%, and the same was true for an additional mutant, NP(1-481)flag (data not shown). Therefore, the NP-VP35 interaction is not sufficient to support replication and transcription in the EBOV trVLP assay.

FIG 4.

NP 481-500 region is required for IB formation and association with VP35. (A) Localization of coexpressed NP deletion mutants with VP35 in transfected HuH-7 cells. VP35 was detected with anti-VP35 antibody (green), and NP-FLAG proteins were detected with anti-FLAG antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 dye (blue). (B) Deletion mutants of myc-tagged NP (NP-myc) and VP35-FLAG were coexpressed in 293T/17 cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins and lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and detected by anti-myc or anti-FLAG antibodies, as indicated. A GAPDH antibody was used for the loading control.

Physical interactions between myc-tagged NP and FLAG-tagged VP35 were examined next. As shown in Fig. 4B, full-length NP, NP(1-641), and NP(1-500) coimmunoprecipitated with VP35, but NP(1-481) and NP(1-450) did not. Identical results were observed using VP35-myc and NP-FLAG constructs (i.e., reversed epitope tags) by immunoprecipitation with anti-myc antibody (data not shown). Thus, our results with coimmunoprecipitation of NP deletion mutants and VP35 were completely aligned with IB colocalization of the identical NP deletion mutants and VP35 (Fig. 4A). We conclude that the NP 481-500 region is important for both VP35 association and for IB formation.

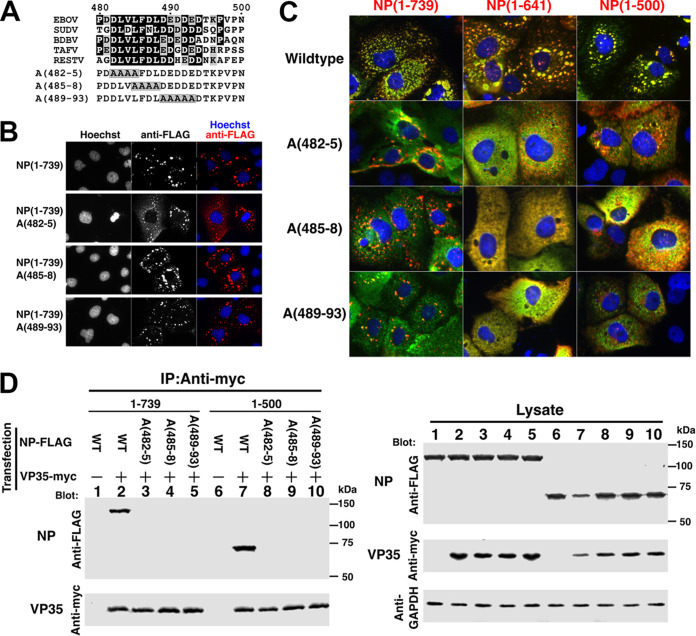

A highly conserved acidic/hydrophobic patch in NP 481-494 region interacts with VP35.

Based on our deletion analysis, we noticed that the 481-500 region contains a highly conserved acidic/hydrophobic patch, specifically focused within aa 481 to 494. Sequence conservation is observed across five Ebolavirus members, including EBOV, whose sequence in this region consists solely of acidic and hydrophobic residues (Fig. 5A). To examine the importance of this region, three alanine-scanning mutants were constructed to interrogate the possibly redundant activities of the constituent residues. As such, each mutation converted 4 or 5 consecutive residues to alanine stretches (Fig. 5A). Initially, the mutants were tested in the context of full-length NP expressed alone, but none of them, namely, A(482-5), A(485-8), or A(489-93), had any effect on IB formation (Fig. 5B). We interpret this result to be due to the presence of an intact NP-Ct in the full-length protein, which provided the redundant IB formation function. We also tested the localization of NP(1-641) or NP(1-500) with our three alanine-scanning mutants. As expected, due to the lack of NP-Ct, these mutants were distributed in the cytosol and no IB localization was observed (data not shown). We next tested whether the same mutations affect IB formation by NP(1-739), NP(1-641), or NP(1-500) in the presence of VP35. As shown in Fig. 5C, all NPs retaining wild-type sequences within the 481-494 region colocalized with VP35 in IBs (top panel). Also, full-length NP(1-739), containing alanine-scanning mutations, localized to IBs, as expected due to the presence of NP-Ct. Importantly, however, VP35 overwhelmingly distributed to the cytosol in the presence of NPs containing any of the alanine-scanning mutants. There was some minor colocalization of VP35 and NPs with the A(482-5) or A(489-93) mutation, but even in those cases most VP35 clearly spread widely in the cytosol and not in IBs. This indicates that the NP 481-494 region is required for the localization of VP35 in NP-induced IBs. In the case of alanine-scanning mutations within NP(1-641) and NP(1-500), both of which lack NP-Ct, no IB colocalization with VP35 was observed. These data clearly suggest physical interaction between the NP 481-494 region and VP35, and that this interaction can establish localization at IBs through VP35-NP complex formation.

FIG 5.

Alanine-scanning mutants covering the NP 482-493 region abolish IB formation, colocalization, and interaction with VP35. (A) Sequence alignment of five Ebolavirus species members and sequences of alanine-scanning mutants within EBOV. Identical residues are shown with white letters on black background, and similar residues are shown with black letters on gray background. Alanine mutations are boxed. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of wild-type and alanine-scanning mutants of full-length NP. FLAG-tagged NP and mutants were stained with anti-FLAG antibody (red) and Hoechst 33342 dye (blue). (C) NP(1-739), NP(1-641), and NP(1-500), or their corresponding alanine-scanning mutants, were coexpressed with VP35. Cells were stained with anti-FLAG antibody (NP; red), and VP35 was stained with anti-VP35 antibody (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Merged green/red fields are shown. (D) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of coexpressed VP35-myc and wild-type or alanine-scanning mutants of FLAG-tagged NP(1-739) or NP(1-500). Cells were cotransfected with VP35-myc and NP-FLAG derivatives, lysed, and processed for immunoprecipitation as described in Materials and Methods. A GAPDH antibody was used for the loading control. (Left) Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies. (Right) Crude lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies to determine protein expression levels.

To further test this hypothesis, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays of NP mutants within the 481-494 region (Fig. 5D). In the full-length NP(1-739) context, VP35-myc associated with wild-type NP-FLAG but did not pull down any of the three alanine-scanning mutants. The identical result was obtained in the context of NP(1-500) containing each of the alanine-scanning mutations. Thus, from colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation experiments, we conclude that the NP 481-500 region, particularly 481-494, is important for the interaction between NP and VP35.

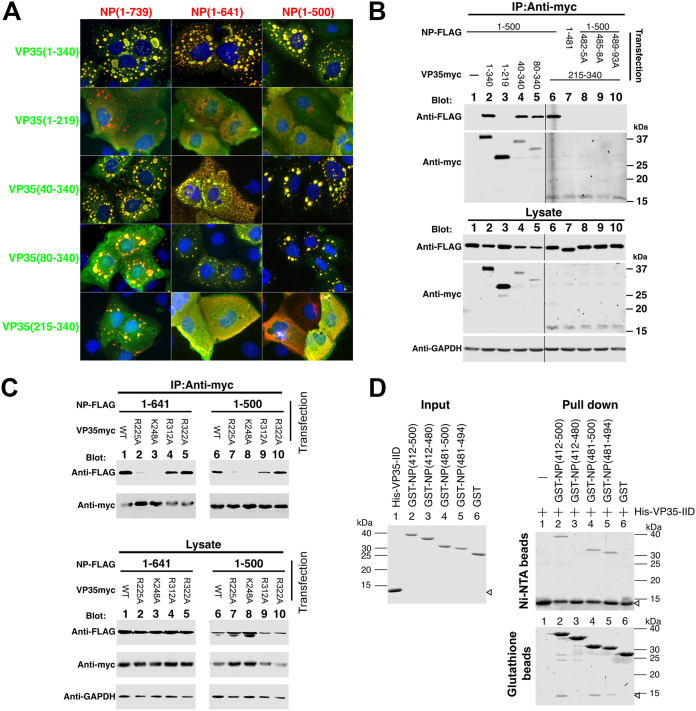

The IFN inhibitory domain of VP35 is required for NP-VP35 association and colocalization at IBs.

Previously, the NPBP (NP binding peptide) of VP35 (aa 20 to 48) was shown to interact with the NP N-terminal domain (43, 44). NPBP binding is essential for RNA replication and transcription, and it inhibits NP oligomerization and also preserves NP in an RNA-free state (43, 44). We tested whether mutation of the NPBP sequence affects the ability of VP35 to complement deletion of NP-Ct in the formation of IBs. However, the mutation of crucial NPBP residues L33D and M34P (43) had no effect on IB formation (not shown). Further deletions of VP35 were constructed to explore the domain(s) responsible for complementing the NP-Ct deletion. As shown in Fig. 6A, full-length VP35(1-340) colocalized with NP(1-739), NP(1-641), and NP(1-500). Interestingly, VP35(1-219), lacking the interferon inhibitory domain (IID) located within aa 221 to 340, failed to colocalize with NP in IBs or to complement NP-Ct deletion mutants NP(1-641) and NP(1-500). VP35(40-340), which lacks most of the NPBP sequence, did colocalize with all NPs in IBs [full length, NP(1-641), and NP(1-500)]. VP35(80-340), which completely lacks the NPBP sequence, also colocalized with all NPs and localized in IBs.

FIG 6.

VP35 IID associates with the NP(481-500) region. (A) Localization of deletion mutants of VP35 and NP. Wild-type and deletion mutants of NP were cotransfected with wild-type VP35 and deletion mutants in HuH-7 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were stained with anti-FLAG (NP, red) and anti-myc (VP35, green). Merged green/red fields are shown. (B) NP(1-500) and related mutants, as indicated, were cotransfected with wild-type VP35-myc and deletion mutants in 293T/17 cells, and cells were lysed 48 to 50 h after transfection. An anti-myc antibody was used for immunoprecipitation, and coimmunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. GAPDH is the loading control of the lysate. (Top) Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies. (Bottom) Crude lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies to determine protein expression levels. For the top and bottom panels, the left and right sides of the data shown were sourced from the same image, with several lanes deleted between lanes 5 and 6. This is indicated by vertical black lines. (C) NP(1-500) and NP(1-641) were cotransfected with wild-type VP35-myc or the indicated mutants in 293T/17 cells, and cells were lysed 48 to 50 h after transfection. An anti-myc antibody was used for immunoprecipitation, and coimmunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (Top) Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies. (Bottom) Crude lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies to determine protein expression levels. (D) Pulldown assay of E. coli-expressed proteins. GST-NPs with the indicated regions of NP or His-tagged VP35-IID were expressed in E. coli and purified using glutathione Sepharose or nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose. Purified proteins were dialyzed, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and stained with CBB (input). Purified proteins were quantified, and equal amounts of GST-NPs or GST were mixed with His-VP35-IID protein. After overnight incubation with the indicated beads followed by washing, protein bound to the beads was extracted with 2× sample buffer, and equal volumes of the eluents were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB.

As expected, IBs were observed when full-length NP(1-739) was coexpressed with VP35(215-340) containing the IID, and the two proteins colocalized. However, the same portion of VP35 did not trigger IB formation when coexpressed with either NP(1-641) or NP(1-500), as shown in Fig. 6A. This indicates that when NP-Ct is missing, VP35 IID is not sufficient to trigger IB formation, even though both NP(1-641) and NP(1-500) can interact with the IID. Therefore, VP35 sequences between aa 80 and 215 are also required for this function.

To test whether VP35 physically associates with the NP 481-500 region, NP(1-500) and its three alanine-scanning mutants were tested for coimmunoprecipitation with VP35 and several of its deletion mutants (Fig. 6B). NP(1-500) coimmunoprecipitated with full-length VP35 (as also shown in Fig. 4B). Consistent with our colocalization data, VP35(1-219), completely lacking the IID, did not associate with NP(1-500). VP35(40-340) and VP35(80-340) did associate with NP(1-500), demonstrating that the NPBP sequence is dispensable for binding of NP(1-500) to VP35. Importantly, VP35(215-340), containing the IID, coimmunoprecipitated with NP(1-500) but not with NP(1-481), NP(1-500/482-5A), NP(1-500/485-8A), or NP(1-500/489-93A), demonstrating that the VP35 IID-NP interaction requires the NP 481-494 region.

Previously, it was shown that the “first basic patch” of the VP35 IID (59) binds to NP and is critically important for RNA synthesis in a minigenome assay (45). To test whether these residues are involved in the interaction with NP(481-500), mutants (R225A and K248A) that abolished minigenome activity and binding to NP (45) were tested by pulldown assays (Fig. 6C). Two additional VP35 mutants in the “central basic patch” (R312A and R322A) were also tested. These mutants abolish dsRNA binding and reduce suppression of IFN-β promoter activation but do not affect minigenome activity or NP binding (60). NP(1-641) and NP(1-500), both containing the NP 481-500 region, were examined for binding to all four VP35 mutants. Importantly, mutants R225A and K248A abolished the binding, but mutants R312A and R322A maintained efficient binding. These data are consistent with those of Prins et al. (45) and suggest that residues within the first basic patch of VP35 IID are required for binding to the NP 481-500 region.

To further confirm the interaction between the NP(481-500) region and VP35-IID, glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of NP(412-500) or its shorter derivatives were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified, as was His-tagged VP35-IID (Fig. 6D, input). Purified proteins then were combined and subjected to pulldown assay. As shown in Fig. 6D, we clearly confirmed the association of GST-NP with His-VP35-IID using constructs containing NP(412-500), NP(481-500), and NP(481-494). No binding was observed with either GST alone or with GST-NP(412-480). These data demonstrate that NP(481-494) is sufficient to bind to VP35 IID and identify it as a novel VP35-binding domain. Importantly, for the data presented in Fig. 6D, purified proteins were used, because this ensured that equivalent amounts of each domain could be strictly compared. To reduce nonspecific binding under these conditions, the protocol was optimized, including elevated salt concentration for higher stringency (see Materials and Methods). The highest salt concentration was 0.5 M NaCl, which demonstrated that the binding was resistant to stringent conditions, including detergent. These conditions reduced the amount of recovered protein; nonetheless, the specificity of binding was demonstrated.

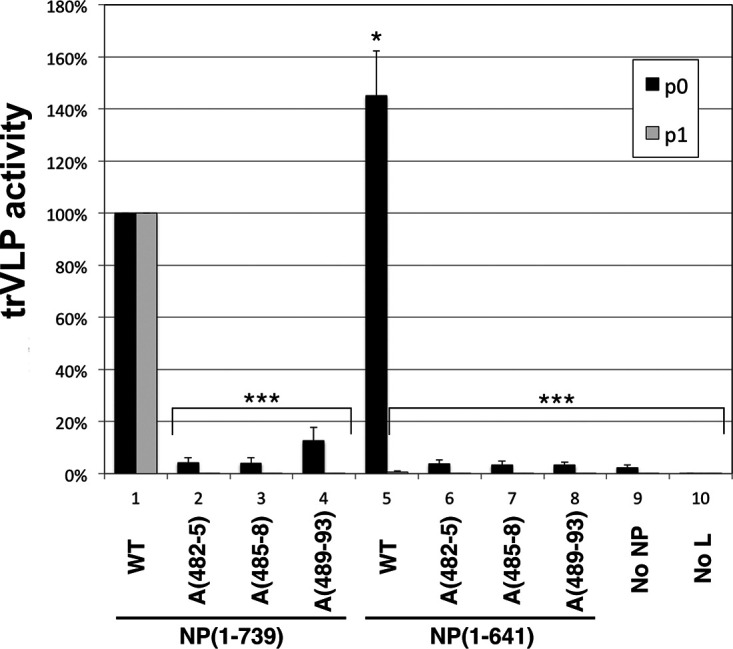

The NP 481-500 region is crucial for EBOV RNA synthesis.

Given the important role of the NP 481-500 region in IB formation and interaction with VP35, and considering the known functions of NP and VP35 in viral RNA synthesis (31), we asked if the NP 481-500 region is important for reporter activity in p0 cells, which is directly dependent on viral transcription and RNA replication (54–56). Accordingly, trVLP assays of our three alanine-scanning mutants and the corresponding wild-type constructs were performed. As shown in Fig. 7, in the context of the full-length NP backbone, all three mutants resulted in strongly reduced reporter activity in p0 cells, amounting to 4 to 12.5% of the activity observed in the context of wild-type NP. Of note, when p1 cells expressing alanine-scanning mutant NPs were infected with wild-type trVLPs from p0 cells, reporter activity in the p1 cells was also strongly reduced, indicating that the mutants were defective in the replication of incoming genomes associated with wild-type nucleocapsids (not shown). Keeping in mind that these mutant NPs still localized in IBs due to the presence of NP-Ct (Fig. 5B and C), we conclude that the NP-VP35 interaction mediated by the NP 481-500 region is, by itself, essential for full transcription/RNA replication activity of EBOV. Similar experiments were also performed within the context of the NP(1-641) backbone lacking NP-Ct. Under these conditions, the activity of the three alanine-scanning mutants was 2.3 to 2.5% of that of control NP(1-641) protein in p0 cells, whereas unmutated NP(1-641) fully supported reporter activity in p0 cells (as also shown in Fig. 1). Considering that the omission of NP altogether from the trVLP assay showed 2.4% of the activity of the complete system (Fig. 7, no NP), clearly these alanine-scanning mutants abolished almost all EBOV RNA synthesis. Taken together, we conclude that NP 481-500 is a crucial region for EBOV replication and, importantly, that its function represents a novel form of regulation at the interface of RNA synthesis and inclusion body dynamics.

FIG 7.

trVLP assay of the wild type and alanine-scanning mutants in aa 481 to 500. For p0 assays, NP(1-739) or NP(1-641) and their alanine-scanning mutants, A(482-5), A(485-8), or A(489-93), were cotransfected with other components of the trVLP p0 assay, and luciferase activity of each lysate was measured. Wild-type NP(1-739) activity was set at 100%. trVLP assays in the absence of NP (No NP) or L (No L) were used as negative controls. For p1 assays, recipient cells were transfected with the complete set of trVLP plasmids, including wild-type NP, and supernatants from the indicated p0 assay were used for infection. Error bars represent the SD from three independent biological replicates. Asterisks indicate P values from comparisons to the corresponding NP(1-739) wild type based on the Student's t test: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

With this report, we have characterized three novel functions of NP, two of which are carried out by NP-Ct and a third controlled by the newly identified aa 481 to 500 central domain (CD). Based on our previous structural studies (50–52) we designed a deletion of NP-Ct that abolished the production of infectious trVLPs in the trVLP assay and also abolished IB formation when NP was expressed alone. In the trVLP assay, despite wild-type levels of transcription/replication that were achieved in p0 cells expressing mutant NP(1-641) (Fig. 1 and 3A), these cells failed to produce infectious trVLPs. Importantly, since p1 cells in the trVLP assay were preloaded with wild-type NP, our results clearly demonstrate that the supernatants from p0 cells contained no infectious trVLPs whose replication would have been supported in p1 cells by the wild-type protein. Further analysis revealed that NP, VP35, VP40, and GP all were detected in similar amounts in comparisons of trVLPs harvested from NP(1-739)- or NP(1-641)-expressing cells. Interestingly, even though the protein composition of the two trVLP types were the same, the amount of genomic RNA recovered from the NP(1-641)-associated trVLPs was only 10% of the wild-type level (Fig. 1E and F). These data clearly suggest that NP-Ct has an important role in genomic RNA incorporation or stability within the VLP nucleocapsids and, as such, defines a novel function for this domain. Our finding that NP(1-641) has wild-type transcription/replication activity in p0 cells is consistent with it containing previously identified binding sites for VP35 and VP30 that support transcription/replication, as well as the novel binding site for VP35 described in this work (the CD), in addition to its other well-characterized N-terminal domain functions (aa 1 to 450) (29, 31, 32).

A second, apparently unrelated function of NP-Ct described here is in the control of IB formation. IB formation accompanies the establishment of viral RNA and nucleocapsid production in the context of viral infection and also in the context of trVLP or minigenome replication. It is well-established that the ectopic expression of NP by itself is sufficient for IB formation (10, 29, 34–37). Our data demonstrate that when NP is expressed alone, IB formation strictly depends on NP-Ct (Fig. 2). However, the expression of NP-Ct alone is not sufficient to trigger IB formation, suggesting that other regions of the protein are also specifically involved. Since mutant NP(410-739) also fails to make IBs (Fig. 2), we conclude that sequences in the N-terminal domain are also required, possibly including the known RNA-binding and/or NP oligomerization functions, to trigger IB formation. Consistent with this, data from Noda et al., using a series of ∼150-aa deletions across NP, showed that only deletion of aa 451 to 600, which retained an intact NP-Nt and NP-Ct, allowed inclusion body localization (36). The mechanism by which NP-Ct contributes to IB formation is not yet known but may involve interactions with cellular proteins in addition to viral protein interactions or structural regulation of NP. As proposed by Kolesnikova et al., NP helices can be observed by electron microscopy in the perinuclear region near endoplasmic reticulum-bound ribosomes, suggesting that these are nucleation sites for spatially directed early viral translation and that this could explain the emergence of IBs in the perinuclear region (29). NP-Ct could conceivably be involved in this process.

We conclude that the two steps of virus replication supported by NP-Ct (infectious VLP production and IB formation) are mechanistically distinct, because in cells that expressed NP(1-641) plus all other trVLP components, intact IBs and transcription/replication were observed (Fig. 3), even though these cells failed to produce infectious trVLPs in p0 supernatants (Fig. 1). This indicates that the failure of NP(1-641) to support infectious trVLP production did not impinge on the process of IB formation. It is interesting, but not necessarily surprising, that the two NP-Ct functions appear mechanistically distinct. The possible roles of NP-Ct in nucleocapsid assembly or overall viral assembly, leading to the production of infectious particles, would be expected to involve, at least in part, NP as a stable component of the intact nucleocapsid within newly generating virions. This would likely be distinct from its role in IB formation, which seems to occur in coordination with newly forming or transcriptionally active nucleocapsids, particularly in light of our data presented here, demonstrating that IB formation and RNA synthesis are both controlled by the NP CD. Indeed, in their cryoelectron tomography studies of MARV and EBOV nucleocapsids from intact virus, Bharat et al. concluded that periodic outward-facing protrusions of the nucleocapsid contain the C-terminal region of NP, in addition to VP24 and VP35 (61, 62), which is consistent with a structural role for the C-terminal region in building or stabilizing new virions. In these studies, the NP C-terminal region was more broadly defined than the focused NP-Ct characterized here; nonetheless, NP-Ct might be expected to reside in the outward-facing protrusions of the nucleocapsid and, therefore, be available to be involved in productive virus assembly, including possible contacts with VP40, to achieve proper assembly (36). Additionally, as we demonstrated in Fig. 1, NP-Ct is required for viral genomic RNA to be found in isolated VLPs.

Importantly, we found that the loss of NP-Ct in deletion NP(1-641) was efficiently complemented by VP35 expression in the formation of IBs, and this correlated with the physical association of NP(1-641) with VP35. Using a combination of deletion and alanine scanning mutations, we identified a novel region of NP (NP 481-500 region) that interacts with the interferon inhibitory domain (IID) of VP35 and is required for IB formation and RNA synthesis in the trVLP assay. We termed this region the NP central domain based on its location between NP-Nt and NP-Ct. We demonstrated that the VP35 IID is sufficient to bind to NP derivatives containing the CD, including a minimal GST-NP(481-494) fusion protein. The NP 481-494 region sequence is highly conserved among five ebolaviruses, and in EBOV it consists of only acidic and hydrophobic residues (Fig. 5A). It was previously shown that VP35 IID binds to NP via basic patch residues in VP35, specifically involving R225, K248, and K251 of VP35, and that mutations in those residues abolished the interaction of VP35 IID with NP (45). In this study, we identified the region of NP responsible for VP35-IID binding. It is likely that the VP35 basic residues bind to the acidic residues in NP aa 481 to 494, because we observed that NP(1-500), which retains the CD, fails to bind VP35 derivatives with mutations in the first basic patch. Prins et al. also found that basic patch mutants R225A and K248A abolished an interaction between VP35 and NP (44), which is consistent with our data. Because inhibition of the VP35-CD interaction severely affects trVLP activity, inhibition of this interaction could be a good target for small-molecule inhibition. Indeed, compounds that inhibit VP35-NP interactions have been identified (63). Our study also raises the question of why there are apparently redundant functions encoded by EBOV to control IB formation, as revealed by complementation of the NP-Ct deletion by VP35 IID. Our finding clearly suggests that even though VP35 supports IB formation in the absence of NP-Ct, fully functional IB formation likely requires both VP35 and NP-Ct. Tools are not currently available to distinguish among potentially different stages of IB function during infection, but these will be interesting to establish. IBs are turning out to be complex structures composed of viral and cellular components, and we speculate that there are interesting, possibly distinct roles for both the NP-Ct and the VP35 binding domain of NP in this process, and that IBs may display different physical and functional properties as infection progresses.

Structural studies by Leung et al. and Kirchdoerfer et al. revealed the binding of a peptide derived from VP35 to the N-terminal domain of NP (43, 44). Binding of the VP35 peptide regulates NP-RNA interactions as well as NP oligomerization, both key requirements for productive RNA synthesis. Moreover, the NP region targeted by the peptide, which crucially involves NP residues R240, K248, and D252, is required for maximal RNA synthesis in minigenome assays (44). These findings are the basis for models in which the binding of the VP35 peptide to the N-terminal domain of NP ensures a monomeric and RNA-free state of NP in preparation for productive replication of viral RNA (43, 44). To this picture we have added the dual roles of the NP CD in controlling both RNA synthesis and IB formation. Our data demonstrate that the CD is responsible for interacting directly with sequences within the IID of VP35 and is also crucially required for RNA synthesis and IB formation. Interestingly, this NP-VP35 interaction efficiently complements the defect in IB formation exhibited by the NP-Ct deletion mutant NP(1-641) when it is expressed alone (Fig. 3). In our experiments, mutation or deletion of residues within the NP-binding VP35 peptide, responsible for controlling RNA binding and NP oligomerization (43, 44), had no effect on the ability of VP35 to complement deletion of NP-Ct or to localize to inclusion bodies (Fig. 6 and accompanying text in Results), clearly indicating that the two NP-binding functions of VP35 are separate. This raises interesting questions about the relationship between these two functions of VP35 in supporting RNA synthesis and nucleocapsid assembly. The fact that VP35 interacts directly with NP at two distinct sites could influence the affinity of the individual interactions or the avidity of the overall interaction. One interesting possibility is that the interaction of VP35 IID with the NP CD might prime or enhance the NPBP-NP interaction due to structural influences, thereby allowing the regulation of NP oligomerization and NP-RNA binding. Figure 8 illustrates the two binding sites within NP for VP35, as defined in this work and by others for the NPBP region of VP35 (43, 44). In addition, Fig. 8 illustrates the regions shown here involved in the control of IB formation and production of infectious trVLPs. Further work will be required to understand these interesting relationships.

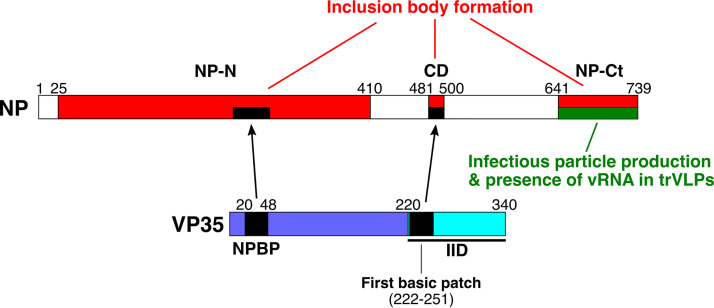

FIG 8.

Identified NP functions. Full-length NP and VP35 proteins are illustrated. NP-N and NP-Ct cover aa 1 to 412 and 641 to 739, respectively, as defined in reference 51. The central domain (CD) spans aa 481 to 500. Red boxes, regions required for IB formation. The large region spanning aa 25 to 410 is based on data shown in Fig. 2B. The requirement for NP-Ct applies to NP-induced IBs, and when VP35 is coexpressed, NP-Ct is not required, as described in the text. Likewise, when NP-N and NP-Ct are present, mutation of the CD does not abolish IB formation; therefore, NP-Ct and CD complement each other. The green box indicates the region required for production of infectious trVLPs and incorporation/retention of viral RNA in purified trVLPs. For NP and VP35, black regions indicate NPBP and its corresponding binding region within NP, the VP35 first basic patch as defined in references 45 and 60, and its corresponding binding region, the CD. See references 43 and 44 for definitions of NP region bound by NPBP. See Discussion for possible functional relationships between the two regions of VP35 that interact with NP.

Some common themes have emerged from the study of inclusion bodies generated by pathogenic negative-strand RNA viruses. These include the housing of RNA synthesis machinery, protection from innate immune mechanisms, and association with certain host proteins (although there is not yet strong commonality among the different viruses regarding the identity of these proteins or their function in replication). In some cases there is good evidence that the structure of IBs is achieved by liquid-phase separation (26, 27), which is mediated by the activity of specific viral proteins. For EBOV, NP has a central role in IB formation, but there is no evidence so far of a protein shell, phase separation, or another process that distinguishes inside from outside. Rather, electron microscopic analysis indicates that IBs contain an accumulation of arrays of growing or fully assembled nucleocapsids when cells are infected with live virus or transfected with various nucleocapsid components, including NP (10, 42). Several groups also have reported colocalization with cellular proteins, strongly suggesting that IBs are more than simply accumulations of nucleocapsids that serve as RNA synthesis factories (19, 20, 24). Regardless, whereas the molecular basis for IB formation remains a mystery overall, our results showing the involvement of NP-Ct and the NP CD support a model wherein the earliest steps of IB formation are controlled by NP and its interaction with VP35. However, despite the fact that a small domain of NP is sufficient for direct binding to VP35 and that this interaction controls both IB formation and RNA synthesis, we do not yet know if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between IB formation and RNA synthesis or whether these two processes are concerted yet mechanistically independent. Clearly, RNA synthesis is not a prerequisite for IB formation. One striking example of this is when all components of the trVLP system are expressed in p0 cells, with the exception of the L polymerase, and this results in robust IB formation but no transcription/replication (Fig. 1 and 3A). This situation also occurs when full-length NPs containing CD mutations are included in the trVLP assay; again, IBs are formed yet transcription/replication is highly defective (Fig. 5C and 7). In this case, however, the IBs do not contain VP35 due to mutation of the CD (Fig. 5C and 6B). These results are consistent with two models. In one model, IB formation and transcription/replication are independent processes, and both are dependent on the interaction between NP CD and VP35. In the second model, transcription/replication strictly depends on IB formation, which depends on VP35 binding to NP. Further investigation of the molecular components of IBs (including the makeup of IBs at different stages of virus replication) will be required to fully distinguish among IB functional models. An interesting but unresolved issue is how, at the molecular level, the NP C-terminal domain is involved in viral RNA packaging or retention and what exact role the complementing activity of VP35 toward the C-terminal domain plays during infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

All plasmids for the trVLP assay, i.e., pCAGGS-NP, pCAGGS-VP35, pCAGGS-VP30, pCAGGS-L, p4cis-vRNA-RLuc, pCAGGS-T7, pCAGGS-Tim1, and pCAGGS-luc2, were described previously (64). pCAGGS-NP-FLAG and pCAGGS-VP35myc were made from pCAGGS-NP and pCAGGS-VP35 (55), respectively. All deletions and mutants of pCAGGS-NP-FLAG and pCAGGS-VP35myc were made by using standard PCR and cloning methods. Synthesized sequence of the VP35 IID (aa 215 to 340) was cloned in pET45b (Novagen) to make His-tagged VP35 IID. PCR-amplified fragments of the NP(412-500) or shorter fragments from pCAGGS-NP were cloned into pGEX-6P-2 (GE Healthcare). All sequences of the cloned or mutated DNA regions of the plasmids were validated by Sanger DNA sequencing.

Cells and transfection.

293T/17 cells and HuH-7 cells were grown in the media indicated in references 65 and 54, respectively. Both cell lines were transfected using TransiT-LT1 (Mirus) according to Biedenkopf and Hoenen (54), except reverse transfection was performed.

Immunoprecipitation.

Forty to forty-eight hours after the transfection, 293T/17 cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) with Pierce protease inhibitor mini tablets, EDTA-free (Thermo Scientific). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Identical amounts of protein in lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation. Myc-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated using mouse anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling) and rProtein A agarose (Genesee). Identical amounts of lysates were incubated with antibody overnight, and then rProtein A agarose was added and incubated for 1 h. Agarose beads were washed with lysis buffer A 4 times. Proteins bound to the beads were eluted with 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Equal volumes of eluents were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Western blotting.

Samples were prepared 40 to 48 h after transfection by lysing the cells in 60 mM Tris, pH 6.8, and 2% SDS. After harvesting the lysates, they were sonicated briefly and measured for protein concentration. Identical amounts of protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-FL membrane (Millipore). Immunoprecipitated samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-FL membrane (Millipore). FLAG-tagged and myc-tagged proteins were detected with rabbit anti-DYKDDDDK (FLAG) monoclonal antibody and rabbit anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling), respectively. For Western blotting of trVLPs, the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-NP antibody (Genetex), mouse monoclonal anti-VP35 (Kerafast), mouse monoclonal anti-GP, H3C8 (a gift from Judy White), and rabbit anti-VP40 (IBT Bioservices). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mouse monoclonal antibody (Millipore) was used for the loading control. Goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with IRDye 680RD and goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with IRDye 800CW were used as secondary antibodies. Odyssey CLx (Li-Cor) was used to scan the membranes.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Expression plasmids of the proteins indicated in the figures were transfected into HuH-7 cells and plated on coverslips in 6-well plates. “All trVLP” is the combination of following: pCAGGS expression plasmids encoding NP-FLAG or NP(1-641)-FLAG (125 ng/well), VP35 (125 ng/well), VP30 (75 ng/well), L (1,000 ng/well), and T7-polymerase (250 ng/well) and a p4cis-vRNA-RLuc plasmid (250 ng/well). Forty to Forty-eight hours after the transfection, cells were washed once with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS. After permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, cells were blocked with 1× diluted Odyssey blocking buffer (PBS) (Li-Cor). Cells were stained with the primary antibodies anti-DYKDDDDK, anti-myc antibody (Cell Signaling), and/or mouse anti-VP35 antibody (Kerafast) and then stained with secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L). The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 dye. Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) was used for mounting.

trVLP assay.

trVLP assays were performed according to Hoenen et al. (55), except that reverse transfection was performed. pCAGGS-NP was replaced with pCAGGS-NP-FLAG or its derivatives in either p0 or p1 cells as indicated in the figures.

Protein and RNA analyses of isolated trVLPs.

Procedures for analyses are described in Watt et al. (56), with minor modifications. For Western blotting of purified trVPLs, 24 ml of cell supernatant (72 h after transfection) was harvested and centrifuged twice at 2,500 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris and then concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion in an SW-32 rotor at 25,000 rpm for 2.5 h at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 140 μl of PBS, and 47 μl of 4× sample buffer was added. Equivalent volumes of samples were subjected to Western blot analysis. For RNA quantification, RNA was purified from 280 μl VLP-containing supernatant using a QIAamp viral RNA (vRNA) minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sixteen microliters of RNA was subjected to a 30-min DNase digestion using 2 μl DNase I (Thermo Scientific) in a total volume of 20 μl according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Digested RNA (7.5 μl) was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the primer 5′-CGGACACACAAAAAGAAAGAAG-3′. Five microliters of the resulting cDNA was amplified by touchdown PCR (10 cycles of annealing at 59 to 54°C for 30 s, followed by 10 cycles of annealing at 54°C for 30 s) using Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the primers 5′-CTTGACATCTCTGAGGCAAC-3′ and 5′-ATGCAGGGGCAAAGTCATTAG-3′. One microliter of PCR product then was subjected to standard PCR with Taq polymerase using the primers 5′-CGAACCACATGATTGGACCAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTATCAGACCTCCGCATTAATC-3′. Quantification standards were included in each PCR at the stage of the first amplification. Known amounts of minigenome DNA were amplified along with reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) under the same conditions and quantified to establish the linear range of amplification. A linear range of amplification was verified from the standards for all trVLP samples. The intensity of bands after agarose gel electrophoresis was measured using the Molecular Imager XRS system and quantified with Image Lab (Bio-Rad).

Pulldown assay of E.coli-expressed proteins.

His-tagged VP35 IID (VP35 aa 215 to 340) and GST-NP (aa 412 to 500) or shorter variants were expressed in the BL21 CodonPlus strain (Agilent Technologies). Cells were lysed in buffer, termed buffer (0.15) (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 20% glycerol), with Pierce protease inhibitor mini tablets, EDTA-free (Thermo Scientific), and 0.1 mg/ml of lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich), and then the suspension was sonicated. After centrifugation, supernatants were subjected to purification using either HIS-Select HF nickel affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) or glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). Purification was confirmed by gel electrophoresis and Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining. After dialysis with Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis devices, 3.5K molecular weight cutoff (Thermo Scientific), purified proteins were quantified by a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentration was set to 1 μM His-tagged proteins and to 2 μM GST-tagged proteins for HIS-Select HF nickel affinity gel pulldown and was set to 1 μM GST-tagged proteins and to 2 μM His fusion proteins for glutathione Sepharose 4B pulldown. Purified proteins were mixed as indicated in the figure legends and rotated with either HIS-Select HF nickel affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) or glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) overnight. Beads were washed twice with buffer (0.15) with 0.1% NP-40, once with buffer (0.35), and once with buffer (0.5), which are identical to buffer (0.15) with 0.1% NP-40 but included 0.35 M and 0.5 M NaCl, respectively. Samples were washed once again with buffer (0.15) containing 0.1% NP-40. Proteins on the beads were eluted with 2× sample buffer. Identical volumes of the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by NIH grant 1R21AI130420 to D.A.E.

We thank Elizabeth Nelson and Judy White for reagents and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coltart CE, Lindsey B, Ghinai I, Johnson AM, Heymann DL. 2017. The Ebola outbreak, 2013-2016: old lessons for new epidemics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 37:220160297. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilunga Kalenga O, Moeti M, Sparrow A, Nguyen VK, Lucey D, Ghebreyesus TA. 2019. The ongoing ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018-2019. N Engl J Med 381:373–383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1904253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong G, Mendoza EJ, Plummer FA, Gao GF, Kobinger GP, Qiu X. 2018. From bench to almost bedside: the long road to a licensed Ebola virus vaccine. Expert Opin Biol Ther 18:159–173. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1404572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green A. 2017. Ebola outbreak in the DR Congo. Lancet 389:2092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cifuentes-Munoz N, Branttie J, Slaughter KB, Dutch RE. 2017. Human metapneumovirus induces formation of inclusion bodies for efficient genome replication and transcription. J Virol 91:e01282-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01282-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S, Chen L, Zhang G, Yan Q, Yang X, Ding B, Tang Q, Sun S, Hu Z, Chen M. 2013. An amino acid of human parainfluenza virus type 3 nucleoprotein is critical for template function and cytoplasmic inclusion body formation. J Virol 87:12457–12470. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01565-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia J, Garcia-Barreno B, Vivo A, Melero JA. 1993. Cytoplasmic inclusions of respiratory syncytial virus-infected cells: formation of inclusion bodies in transfected cells that coexpress the nucleoprotein, the phosphoprotein, and the 22K protein. Virology 195:243–247. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rincheval V, Lelek M, Gault E, Bouillier C, Sitterlin D, Blouquit-Laye S, Galloux M, Zimmer C, Eleouet JF, Rameix-Welti MA. 2017. Functional organization of cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in cells infected by respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Commun 8:563. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00655-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norrby E, Marusyk H, Orvell C. 1970. Morphogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus in a green monkey kidney cell line (Vero). J Virol 6:237–242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.6.2.237-242.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolesnikova L, Muhlberger E, Ryabchikova E, Becker S. 2000. Ultrastructural organization of recombinant Marburg virus nucleoprotein: comparison with Marburg virus inclusions. J Virol 74:3899–3904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3899-3904.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB. 1995. Differentiation of filoviruses by electron microscopy. Virus Res 39:129–150. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrich BS, Cureton DK, Rahmeh AA, Whelan SP. 2010. Protein expression redirects vesicular stomatitis virus RNA synthesis to cytoplasmic inclusions. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000958. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derdowski A, Peters TR, Glover N, Qian R, Utley TJ, Burnett A, Williams JV, Spearman P, Crowe JE Jr. 2008. Human metapneumovirus nucleoprotein and phosphoprotein interact and provide the minimal requirements for inclusion body formation. J Gen Virol 89:2698–2708. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004051-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das SC, Nayak D, Zhou Y, Pattnaik AK. 2006. Visualization of intracellular transport of vesicular stomatitis virus nucleocapsids in living cells. J Virol 80:6368–6377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00211-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringel M, Heiner A, Behner L, Halwe S, Sauerhering L, Becker N, Dietzel E, Sawatsky B, Kolesnikova L, Maisner A. 2019. Nipah virus induces two inclusion body populations: identification of novel inclusions at the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007733. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahaye X, Vidy A, Pomier C, Obiang L, Harper F, Gaudin Y, Blondel D. 2009. Functional characterization of Negri bodies (NBs) in rabies virus-infected cells: evidence that NBs are sites of viral transcription and replication. J Virol 83:7948–7958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00554-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoenen T, Shabman RS, Groseth A, Herwig A, Weber M, Schudt G, Dolnik O, Basler CF, Becker S, Feldmann H. 2012. Inclusion bodies are a site of ebolavirus replication. J Virol 86:11779–11788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olejnik J, Ryabchikova E, Corley RB, Muhlberger E. 2011. Intracellular events and cell fate in filovirus infection. Viruses 3:1501–1531. doi: 10.3390/v3081501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolnik O, Stevermann L, Kolesnikova L, Becker S. 2015. Marburg virus inclusions: a virus-induced microcompartment and interface to multivesicular bodies and the late endosomal compartment. Eur J Cell Biol 94:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson EV, Schmidt KM, Deflubé LR, Doğanay S, Banadyga L, Olejnik J, Hume AJ, Ryabchikova E, Ebihara H, Kedersha N, Ha T, Mühlberger E. 2016. Ebola virus does not induce stress granule formation during infection and sequesters stress granule proteins within viral inclusions. J Virol 90:7268–7284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00459-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindquist ME, Lifland AW, Utley TJ, Santangelo PJ, Crowe JE Jr. 2010. Respiratory syncytial virus induces host RNA stress granules to facilitate viral replication. J Virol 84:12274–12284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00260-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lifland AW, Jung J, Alonas E, Zurla C, Crowe JE Jr, Santangelo PJ. 2012. Human respiratory syncytial virus nucleoprotein and inclusion bodies antagonize the innate immune response mediated by MDA5 and MAVS. J Virol 86:8245–8258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00215-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fricke J, Koo LY, Brown CR, Collins PL. 2013. p38 and OGT sequestration into viral inclusion bodies in cells infected with human respiratory syncytial virus suppresses MK2 activities and stress granule assembly. J Virol 87:1333–1347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02263-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang J, Pietzsch C, Ramanathan P, Santos RI, Ilinykh PA, Garcia-Blanco MA, Bukreyev A, Bradrick SS. 2018. Staufen1 interacts with multiple components of the ebola virus ribonucleoprotein and enhances viral RNA synthesis. mBio 9:e01771-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01771-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wendt L, Brandt J, Bodmer BS, Reiche S, Schmidt ML, Traeger S, Hoenen T. 2020. The Ebola virus nucleoprotein recruits the nuclear RNA export factor NXF1 into inclusion bodies to facilitate viral protein expression. Cells 9:187. doi: 10.3390/cells9010187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikolic J, Le Bars R, Lama Z, Scrima N, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Gaudin Y, Blondel D. 2017. Negri bodies are viral factories with properties of liquid organelles. Nat Commun 8:58. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinrich BS, Maliga Z, Stein DA, Hyman AA, Whelan S. 2018. Phase transitions drive the formation of vesicular stomatitis virus replication compartments. mBio 9:e02290-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02290-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolic J, Civas A, Lama Z, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Blondel D. 2016. Rabies virus infection induces the formation of stress granules closely connected to the viral factories. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005942. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolesnikova L, Nanbo A, Becker S, Kawaoka Y. 2017. Inside the cell: assembly of filoviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 411:353–380. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nanbo A, Watanabe S, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. 2013. The spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of Ebola virus proteins and RNA in infected cells. Sci Rep 3:1206. doi: 10.1038/srep01206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basler CF, Krogan NJ, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK. 2019. Virus and host interactions critical for filoviral RNA synthesis as therapeutic targets. Antiviral Res 162:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirchdoerfer RN, Wasserman H, Amarasinghe GK, Saphire EO. 2017. Filovirus structural biology: the molecules in the machine. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 411:381–417. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda T, Ebihara H, Muramoto Y, Fujii K, Takada A, Sagara H, Kim JH, Kida H, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Assembly and budding of Ebolavirus. PLoS Pathog 2:e99. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker S, Rinne C, Hofsass U, Klenk HD, Muhlberger E. 1998. Interactions of Marburg virus nucleocapsid proteins. Virology 249:406–417. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groseth A, Charton JE, Sauerborn M, Feldmann F, Jones SM, Hoenen T, Feldmann H. 2009. The Ebola virus ribonucleoprotein complex: a novel VP30-L interaction identified. Virus Res 140:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noda T, Watanabe S, Sagara H, Kawaoka Y. 2007. Mapping of the VP40-binding regions of the nucleoprotein of Ebola virus. J Virol 81:3554–3562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02183-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modrof J, Moritz C, Kolesnikova L, Konakova T, Hartlieb B, Randolf A, Muhlberger E, Becker S. 2001. Phosphorylation of Marburg virus VP30 at serines 40 and 42 is critical for its interaction with NP inclusions. Virology 287:171–182. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mateo M, Reid SP, Leung LW, Basler CF, Volchkov VE. 2010. Ebolavirus VP24 binding to karyopherins is required for inhibition of interferon signaling. J Virol 84:1169–1175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01372-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehmann Y, Enterlein S, Randolf A, Muhlberger E. 2005. A reconstituted replication and transcription system for Ebola virus Reston and comparison with Ebola virus Zaire. Virology 332:406–417. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muhlberger E, Lotfering B, Klenk HD, Becker S. 1998. Three of the four nucleocapsid proteins of Marburg virus, NP, VP35, and L, are sufficient to mediate replication and transcription of Marburg virus-specific monocistronic minigenomes. J Virol 72:8756–8764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.11.8756-8764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leung DW, Prins KC, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2010. Ebolavirus VP35 is a multifunctional virulence factor. Virulence 1:526–531. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Y, Xu L, Sun Y, Nabel GJ. 2002. The assembly of Ebola virus nucleocapsid requires virion-associated proteins 35 and 24 and posttranslational modification of nucleoprotein. Mol Cell 10:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirchdoerfer RN, Abelson DM, Li S, Wood MR, Saphire EO. 2015. Assembly of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein from a chaperoned VP35 complex. Cell Rep 12:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung DW, Borek D, Luthra P, Binning JM, Anantpadma M, Liu G, Harvey IB, Su Z, Endlich-Frazier A, Pan J, Shabman RS, Chiu W, Davey RA, Otwinowski Z, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2015. An intrinsically disordered peptide from Ebola virus VP35 controls viral RNA synthesis by modulating nucleoprotein-RNA interactions. Cell Rep 11:376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prins KC, Binning JM, Shabman RS, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2010. Basic residues within the ebolavirus VP35 protein are required for its viral polymerase cofactor function. J Virol 84:10581–10591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00925-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noda T, Kolesnikova L, Becker S, Kawaoka Y. 2011. The importance of the NP: VP35 ratio in Ebola virus nucleocapsid formation. J Infect Dis 204(Suppl 3):S878–S883. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shu T, Gan T, Bai P, Wang X, Qian Q, Zhou H, Cheng Q, Qiu Y, Yin L, Zhong J, Zhou X. 2019. Ebola virus VP35 has novel NTPase and helicase-like activities. Nucleic Acids Res 47:5837–5851. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messaoudi I, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2015. Filovirus pathogenesis and immune evasion: insights from Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:663–676. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fanunza E, Frau A, Corona A, Tramontano E. 2018. Insights into Ebola virus VP35 and VP24 interferon inhibitory functions and their initial exploitation as drug targets. Infect Disord Drug Targets 19:362–374. doi: 10.2174/1871526519666181123145540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baker LE, Ellena JF, Handing KB, Derewenda U, Utepbergenov D, Engel DA, Derewenda ZS. 2016. Molecular architecture of the nucleoprotein C-terminal domain from the Ebola and Marburg viruses. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 72:49–58. doi: 10.1107/S2059798315021439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dziubańska PJ, Derewenda U, Ellena JF, Engel DA, Derewenda ZS. 2014. The structure of the C-terminal domain of the Zaire ebolavirus nucleoprotein. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 70:2420–2429. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714014710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radwańska MJ, Jaskółowski M, Davydova E, Derewenda U, Miyake T, Engel DA, Kossiakoff AA, Derewenda ZS. 2018. The structure of the C-terminal domain of the nucleoprotein from the Bundibugyo strain of the Ebola virus in complex with a pan-specific synthetic Fab. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74:681–689. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318007878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee W, Tonelli M, Wu C, Aceti DJ, Amarasinghe GK, Markley JL. 2019. Backbone resonance assignments and secondary structure of Ebola nucleoprotein 600-739 construct. Biomol NMR Assign 13:315–319. doi: 10.1007/s12104-019-09898-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biedenkopf N, Hoenen T. 2017. Modeling the Ebolavirus life cycle with transcription and replication-competent viruslike particle assays. Methods Mol Biol 1628:119–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7116-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoenen T, Watt A, Mora A, Feldmann H. 27 Septem Ber 2014. Modeling the lifecycle of Ebola virus under biosafety level 2 conditions with virus-like particles containing tetracistronic minigenomes. J Vis Exp doi: 10.3791/52381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watt A, Moukambi F, Banadyga L, Groseth A, Callison J, Herwig A, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, Hoenen T. 2014. A novel life cycle modeling system for Ebola virus shows a genome length-dependent role of VP24 in virus infectivity. J Virol 88:10511–10524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01272-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirchdoerfer RN, Moyer CL, Abelson DM, Saphire EO. 2016. The Ebola virus VP30-NP interaction is a regulator of viral RNA synthesis. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005937. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu W, Luthra P, Wu C, Batra J, Leung DW, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2017. Ebola virus VP30 and nucleoprotein interactions modulate viral RNA synthesis. Nat Commun 8:15576. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leung DW, Ginder ND, Fulton DB, Nix J, Basler CF, Honzatko RB, Amarasinghe GK. 2009. Structure of the Ebola VP35 interferon inhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:411–416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807854106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leung DW, Prins KC, Borek DM, Farahbakhsh M, Tufariello JM, Ramanan P, Nix JC, Helgeson LA, Otwinowski Z, Honzatko RB, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2010. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition and interferon antagonism by Ebola VP35. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17:165–172. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bharat TA, Noda T, Riches JD, Kraehling V, Kolesnikova L, Becker S, Kawaoka Y, Briggs JA. 2012. Structural dissection of Ebola virus and its assembly determinants using cryo-electron tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4275–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120453109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bharat TA, Riches JD, Kolesnikova L, Welsch S, Krahling V, Davey N, Parsy ML, Becker S, Briggs JA. 2011. Cryo-electron tomography of Marburg virus particles and their morphogenesis within infected cells. PLoS Biol 9:e1001196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown CS, Lee MS, Leung DW, Wang T, Xu W, Luthra P, Anantpadma M, Shabman RS, Melito LM, MacMillan KS, Borek DM, Otwinowski Z, Ramanan P, Stubbs AJ, Peterson DS, Binning JM, Tonelli M, Olson MA, Davey RA, Ready JM, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2014. In silico derived small molecules bind the filovirus VP35 protein and inhibit its polymerase cofactor activity. J Mol Biol 426:2045–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]