Abstract

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) induces weight loss-independent improvements in glucose homeostasis by unknown mechanisms. We sought to identify the metabolic adaptations responsible for these improvements. Nonobese C57BL/6J mice on standard chow underwent SG or sham surgery. Functional testing and indirect calorimetry were used to capture metabolic phenotypes. Tissue-specific glucose uptake was assessed by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) PET/computed tomography, and RNA sequencing was used for gene-expression analysis. In this model, SG induced durable improvements in glucose tolerance in the absence of changes in weight, body composition, or food intake. Indirect calorimetry revealed that SG increased the average respiratory exchange ratio toward 1.0, indicating a weight-independent, systemic shift to carbohydrate utilization. Following SG, orally administered 18-FDG preferentially localized to white adipose depots, showing tissue-specific increases in glucose utilization induced by surgery. Transcriptional analysis with RNA sequencing demonstrated that increased glucose uptake in the visceral adipose tissue was associated with upregulation in transcriptional pathways involved in energy metabolism, adipocyte maturation, and adaptive and innate immune cell chemotaxis and differentiation. SG induces a rapid, weight loss-independent shift toward glucose utilization and transcriptional remodeling of metabolic and immune pathways in visceral adipose tissue. Continued study of this early post-SG physiology may lead to a better understanding of the anti-diabetic mechanisms of bariatric surgery.

Keywords: diabetes, glucose utilization, immunometabolism, respiratory exchange ratio, sleeve gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Bariatric surgery in the form of sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has become the most performed metabolic surgery in the United States. SG leads to rapid and durable improvements in type 2 diabetes (T2D), and this effect often precedes weight loss (31, 49, 61, 73). In fact, nearly 40% of patients with diabetes who undergo SG leave the hospital without needing anti-diabetic medications (33). Interestingly, there has also been increasing evidence that nonobese, metabolically unhealthy patients can have remission of T2D following surgical intervention (63). Thus clinically, there are weight loss-independent, SG-induced adaptations that lead to improved glucose homeostasis.

Multiple preclinical and clinical studies, aimed at identifying the molecular basis for post-SG T2D remission, show that surgery leads to complex changes in incretin hormone and bile acid production, changes in gut microbial composition, intestinal cellular adaptation, and immune modulation (3, 11, 26). However, multiple authors have revealed that whereas these processes play a role in postsurgical T2D remission, they are not sufficient in and of themselves to cause remission (17, 59, 64, 67).

Furthermore, it is unclear which of these changes, if any, are responsible for the early weight loss-independent T2D improvement seen clinically. Most investigators have tried to address this by using sham pair feeding in obese mouse models. They show that SG can lead to adipose adaptive immune cell changes, improved muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity, and reduced hepatic steatosis in the absence of significant weight loss.

One major limitation to studies carried out in obese models is that the animals lose weight following surgery and are maintained on high-fat diets indefinitely. This makes it increasingly difficult to define the SG-, weight loss-, and diet-specific changes that are occurring after SG.

The use of models in normal chow-fed animals can provide some clarity. Albaugh et al. (2) showed that improvements in glucose tolerance following biliary diversion are dependent on the farnesoid X receptor (FXR)-glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) axis, and in a nonobese rat model, Kulkarni et al. (35) showed that increased gastric emptying and gastric fundal removal were key to post-SG physiology.

Here, we describe a novel model of SG in nonobese mice and show that SG leads to weight-independent changes in glucose tolerance. This post-SG phenotype is defined by a global metabolic shift toward increased glucose utilization and appears to lead to, or be the result of, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) immunologic remodeling, glucose sequestration, and glucose use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Eleven-week-old, male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed in a climate-controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle and reared on a normal rodent chow (5% calories from fat; Pico5053; Laboratory Diet, St. Louis, MO). They acclimated for 1 wk before undergoing any procedure. Figure 1 outlines the overall experimental design. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and animals were cared for according to guidelines set forth by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

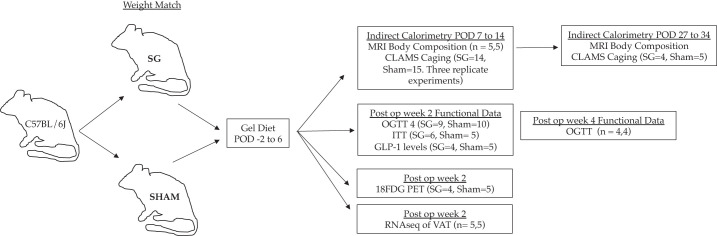

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. 18-FDG, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose; CLAMS, comprehensive lab animal-monitoring systems; GLP1, glucagon-like peptide 1; ITT, insulin tolerance testing; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance testing; POD, postoperative day; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

Sleeve gastrectomy and sham procedures.

Mice were weight matched into two groups and either underwent SG or sham operation. Under isoflurane anesthesia, SG and sham procedures were performed via a small midline laparotomy. In SG, the stomach was dissected free from its surrounding attachments, the short gastric vessels between the stomach and spleen were divided, and a tubular stomach was created by removing 80% and 100% of the glandular and nonglandular stomach, respectively. Sham operation consisted a similar gastric dissection, a short gastric vessel ligation, and manipulation of the stomach along the staple-line equivalent. Short gastric vessel ligation was chosen as part of our control, as ligation of these vessels affects portal venous flow. The signaling through the portal vein has been shown to be important in the body’s ability to sense and respond to glucose (50, 54). Mice were then individually housed thereafter to allow for monitoring of food intake, weight, and behavior. After surgery, SG and sham mice were maintained on the Recovery Gel Diet (Clear H2O, Westbrook, ME) for 6 days and then restarted on normal chow.

Functional glucose testing.

Oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) was performed at postoperative wk 2 and 4, and insulin tolerance testing (ITT) was performed at postoperative wk 2. Animals underwent a 4-h fast (8 AM to noon). During OGTT, mice received 2 mg/g of oral D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and serum glucose levels were measured from the tail vein at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min with a OneTouch Glucometer (Life Technologies, San Diego, CA). ITT was performed by intraperitoneal instillation of 0.6 U/kg of regular human insulin (Eli Lily and Company, Indianapolis, IN) and measurement of serum glucose levels at 15, 30, and 60 min. Baseline glucose was measured for each animal before medication administration. An ELISA assay was used to quantify the concentration of total glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) in circulation, 15 min following glucose gavage, as above (Cat. #81508; Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL). Each functional assay represents a separate animal experiment.

Body composition analysis and comprehensive lab animal-monitoring systems.

A separate group of SG and sham mice was placed into Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring Systems (CLAMS) from postoperative days (POD) 7 to 14 and then again on postoperative days 27 to 34. Body composition of each mouse was determined by MRI spectroscopy. Mice were then placed into individual temperature-controlled cages within CLAMS, which was maintained with a normal, 12-h light/dark cycle at 22°C. Mice had access to food and water ad libitum. Individual mouse CO2 expenditure, O2 consumption, food consumption, and locomotor and ambulatory were collected over the week. The first 24 h of each experiment was discarded to account for mouse acclimation. Energy expenditure (EE) and the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were calculated. CLAMS data were analyzed using the open-source program CalR, as previously described (48). Experimentation from postoperative days 7 to 14 was completed in triplicate, and the data were pooled for analysis (sham n = 14; SG n = 15). A single longitudinal study was completed for CLAMS caging (postoperative days 27 to 34, sham n = 5, SG n = 4).

PET/CT imaging with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose.

Two separate experiments were completed to explore glucose handling in SG mice. Two weeks following SG (n = 2) or sham (n = 2) operations, mice underwent PET/computed tomography (CT) imaging with orally delivered 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG). Mice were placed on a gel diet the day before testing to ensure the stomach was empty of food matter for testing. Each animal was fasted for 4 h before oral 18-FDG gavage. Each mouse was administered 200 μL of 18-FDG, such that there was equivalency in the dose of molar glucose given. Under isoflurane anesthesia, PET/CT experimentation was completed over multiple days to minimize the variation in 18-FDG activity, which varied between 116 and 300 μCI. With the use of PMOD software (PMOD Technologies LLC, Zurich, Switzerland), time-activity curves were created over 60 min, and PET imaging was overlaid onto captured CT images. In a second replicate experiment, SG (n = 2) and sham (n = 3) mice were treated similarly. Mice were euthanized, and whole blood and washed organs were placed into a well counter to assess for overall activity. Data from well counting were pooled between the two experiments (SG n = 4 and sham n = 5). Comparisons between organ standardized uptake values were completed in GraphPad Prism.

RNA-seq of visceral fat.

Two weeks following SG (n = 5) or sham (n = 5) operations, mice were euthanized, and visceral fat (intra-abdominal, epididymal fat pad) was collected (15). Total RNA was extracted, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini; Qiagen). RNA quality was ensured using an Agilent bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were prepared using Roche Kapa RiboErase rRNA depletion-stranded total RNA Hyper Prep sample preparation kits from 100 ng of purified total RNA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The finished dsDNA libraries were quantified by a Qubit fluorometer, Agilent TapeStation 2200, and quantitative RT-PCR, using the Roche Kapa library quantification kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Uniquely indexed libraries were pooled in equimolar ratios and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 with paired-end, 75 bp reads by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Molecular Biology Core Facilities. Sequenced reads were aligned to the University of California, Santa Cruz, mm9 reference genome assembly, and gene counts were quantified using STAR (v2.5.1b) (21). Differential gene-expression testing was performed by DESeq2 (v1.10.1), and normalized read counts (fragments per kilobase million) were calculated using cufflinks (v2.2.1) (43, 68). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis was performed using the Visualization Pipeline for RNA-seq analysis (or VIPER) Snakemake pipeline (16).

The EnrichR platform was used to assess gene-expression ontology (13, 34). Functional enrichment with WikiPathways 2019 Mouse and ChEA2016 Transcription pathway analysis is reported.

Statistics.

GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA), CalR statistical software (48), and the Enrichr platform (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) were used for data analysis. Student’s t tests were used for continuous variables. General linear modeling was used where appropriate with a lean mass covariate. Statistical significance is denoted in figures and text.

Raw RNA-seq data were analyzed with the DESeq2 software platform. A Benjamini-Hochberg correction method was used to correct for multiple comparisons. Table 1 shows the top changes in candidate genes. For this analysis, we included genes with a base greater than 100, fold change greater than 1.0, and adjusted P value less than 0.05.

Table 1.

Top changes in relative gene expression in the visceral fat of SG compared with sham animals

| Upregulation | Downregulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ehhadh | Ldb3 | Ehd3 | Nnat |

| Cxcl13 | Cish | Oxtr | Mroh2a |

| Igj | Ccl8 | Lep | Sfrp5 |

| Atp6v0d2 | |||

Base > 100, log change > 1.0, and adjusted P < 0.05; n = 5.5. Ccl8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 8; Cish, cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein; Cxcl13, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13; Lep, leptin; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

Additionally, genes with a base greater than 50, log-fold change greater than 0.5, and adjusted P value less than 0.05 were used for gene ontology and transcriptional pathway via the Enrichr platform. They are listed in order of their “combined score,” which is the product of the log of Fischer’s exact P value and the z-score (deviation from expected rank).

RESULTS

Weight loss-independent improvements in glucose metabolism following sleeve gastrectomy.

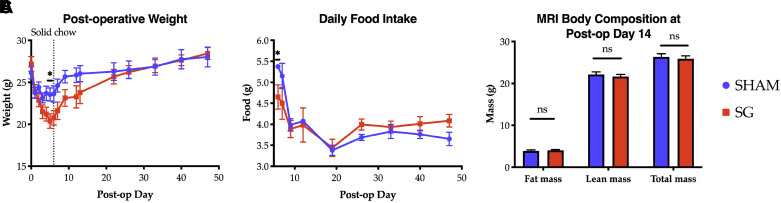

To investigate the weight loss-independent, anti-diabetic effects of SG, we developed a novel model of SG in 11-wk-old C57BL/6J mice reared on standard chow. After a 1-wk acclimation period, mice underwent either SG or sham operation. Whereas there was an initial difference in weight loss in SG mice compared with sham control animals, by postoperative day (POD) 7, mice from both groups showed identical weights (Fig. 2A). Mice were restarted on solid chow on POD 6. By POD 7, overall caloric intake, as measured by daily food weight, was not different between groups (Fig. 2B). Further, MRI body composition analysis revealed that SG mice had reduced fat and lean mass during the first operative week, but by POD 14, all mice had identical body composition (Fig. 2C). Thus this model is well suited to study the weight loss-independent effects of SG.

Fig. 2.

Postoperative weight (A), daily food intake (B), and body composition (C) between sham (n = 4) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG; n = 4) mice. A and B: n = 4.4; C: n = 5.5, and data are representative of 3 biologic replicates. Comparisons by Student’s t tests. *P < 0.05. ns, not significant.

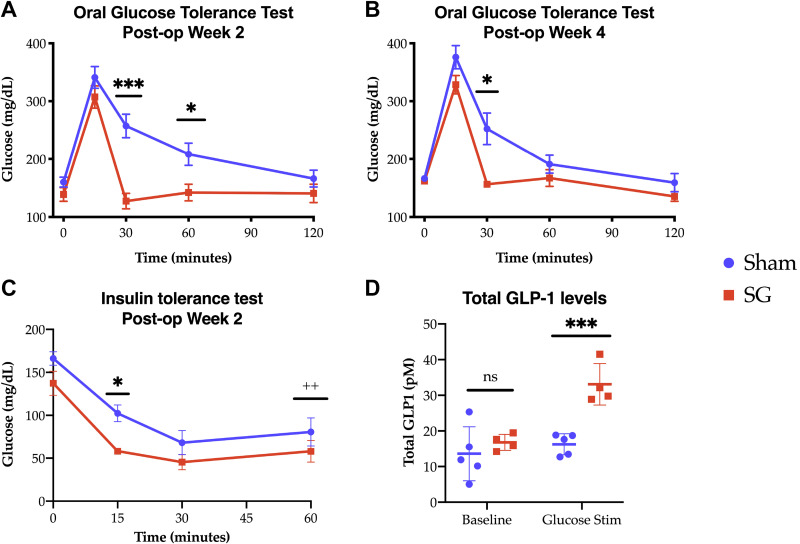

Despite equivalency in weight, caloric intake, and body composition by postoperative day 14, SG mice displayed distinctly different glucose handling compared with their sham counterparts. Oral glucose tolerance testing was performed in the second postoperative week. Whereas SG and sham animals had no difference in fasting or maximal glucose peak, glucose levels in SG animals rapidly cleared, with serum levels dropping nearly 200 mg/dL to baseline levels in the 15 min following maximal glycemia. This change was still evident at 4 wk (Fig. 3, A and B). Additionally, SG animals had a more rapid decline in serum glucose levels during ITT, 2 wk postsurgery (Fig. 3C), although there was no difference in area under the curve between groups (area under the curve sham vs. SG, 5,527 ± 851 vs. 3,792 ± 598, P = 0.127). Of note, during this testing, two SG animals and one sham had to be rescued from hypoglycemia at 60 min. In keeping with the known post-SG physiology in humans, SG mice had increased serum GLP1 levels in response to oral glucose stimulation at 15 min (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrate improved glucose homeostasis in mice following SG, independent of differences in body composition.

Fig. 3.

A and B: oral glucose tolerance testing at 2 and 4 wk, respectively [A: sleeve gastrectomy (SG) n = 9, sham n = 10; B: n = 4.4]. C: insulin tolerance testing at 2 wk (SG n = 6, sham n = 6). D: total glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) levels at 15 min following glucose challenge (SG n = 4, sham n = 5). Comparisons made using t tests. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. ++One sham and 2 SG animals had to be rescued from hypoglycemia at this time point. ns, not significant.

Indirect calorimetry reveals increased carbohydrate utilization in SG mice.

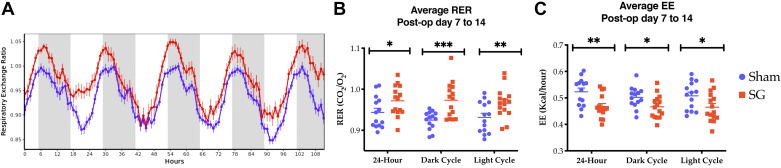

To gain a better understanding of the metabolic changes underlying the observed weight loss-independent improvement in glucose handling by SG mice, we next utilized indirect calorimetry via Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring Systems (CLAMS) to capture the energy balance of these animals. SG and sham mice were placed into CLAMS cages from POD 7 to 14. The most notable change occurred in the respiratory exchange ratio (RER; Supplemental Table S1; all supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9956579). As typical of mice fed a standard rodent chow, the RER of sham animals ranged from 0.85 to 1.0 during light and dark photoperiods, corresponding roughly to periods of fasting and feeding, respectively. In contrast, SG mice had a strikingly high RER, ranging from an average of 0.9 to an average peak near 1.05. RER values greater than 1.0 suggest either increased glucose utilization or a process such as de novo lipogenesis (DNL; Fig. 4, A and B) (10). Importantly, there was equivalency in the total food consumed in a 24-h period and ambulatory activity (Supplemental Table S2). During the first postoperative week, SG mice showed a reduction in the EE across all times of day (Fig. 4C and Supplemental Fig. S1). The effect on EE reduction is consistent with effects seen in food-restriction experiments for weight loss in rodents and humans (38, 58). However, the effect on RER is novel.

Fig. 4.

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) mice have continuously elevated respiratory exchange ratios (RERs; average 0.9–1.05), indicating preferential glucose utilization during both light and dark cycles. A: sham mice demonstrate normal RER excursions, reflective of mixed lipid/glucose utilization. SG mice have higher average RER (B) and lower energy expenditure (EE; C) over a 24-h period during the dark cycle and during the light cycle. Combination of 3 biologic replicates. SG n = 15, sham n = 14; t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

After 2 additional wk of normal housing and daily monitoring, mice were again placed into CLAMS cages (POD 27–34). At this point, SG and sham mice had similar total (26.3 ± 0.31 vs. 25.4 ± 0.33, P = 0.58), fat (4.1 ± 0.3 vs. 4.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.70), and lean (22.0 ± 0.9 vs. 21.6 ± 0.3, P = 0.53) masses. During this week, SG and sham mice had the same caloric intake, overall energy expenditure, and activity level. However, the elevation in the RER after SG persisted (Supplemental Table S3), indicating that changes in RER are durable and important in the underlying physiology of SG.

Positron emission tomography with oral 18-FDG reveals a tissue-glucose sink.

We next sought to identify the tissue responsible for rapid systemic glucose utilization during OGTT and for the RER changes seen in SG mice. Given the known importance of gut-based incretin hormone production in post-SG physiology, orally delivered 18-FDG was administered to sham and SG animals (2, 17, 35).

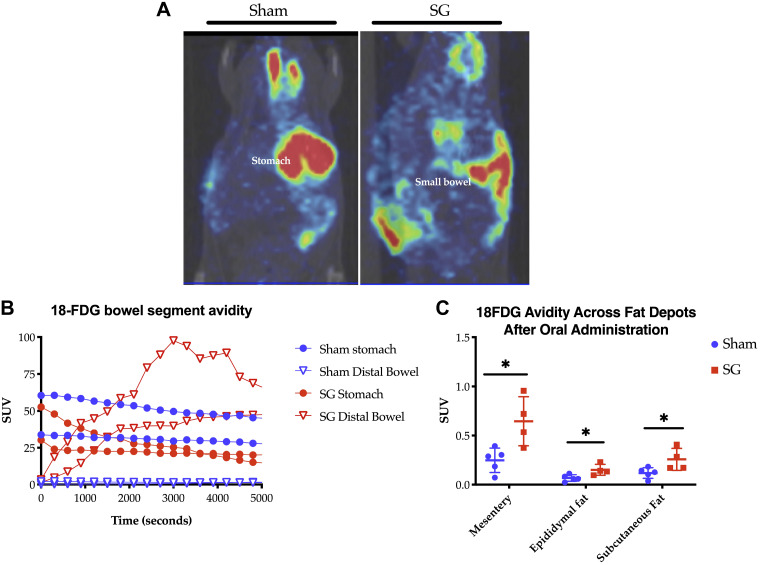

As shown in Fig. 5A, oral delivery of 18-FDG to SG mice led to rapid distal delivery of the glucose analog compared with sham animals. Time-activity curves generated from PET/CT imaging revealed that the glucose analog remained stagnant in the stomach and very proximal small bowel in sham animals, whereas in SG animals, there was rapid gastric clearance and delivery to the distal small bowel within 60 min (Fig. 5B). This is in keeping with prior studies showing increased gastric emptying following SG in animals and humans (6, 9, 12, 35, 47).

Fig. 5.

A: representative PET/computed tomography images from sham (left) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG; right) animals, 1 h after oral 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) administration during postoperative wk 2. Red denotes high and green low 18-FDG avidity. B: time activity curves were generated (n = 2.2). C: 18-FDG avidity across all fat depots, as measured by well counter (C: SG n = 4, sham n = 5). *P < 0.05. SUV, standardized uptake value.

Quantification of 18-FDG avidity by well counter at 90 min showed that most tissues had equivalency in total glucose uptake (Supplemental Table S4). There were no statistically significant differences in bowel-segment avidity. However, there was a significant increase in the avidity of cecal stool in SG animals, suggesting that there is increased luminal transit, as opposed to increased enterocyte uptake and capture of 18-FDG. However, in SG animals, there was increased 18-FDG present across all fat depots tested—mesenteric, epididymal, and subcutaneous—suggesting that metabolic changes within these fat depots could explain the post-SG physiology (Fig. 5C).

RNA sequencing reveals gene-level changes in visceral fat immunity and metabolism.

Metabolic dysregulation and inflammation of the visceral adipose tissue (VAT) are known, potent contributors to the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Thus changes in gene expression and transcriptional programming in this depot may underlie the post-SG improvements. Given the increase in 18-FDG in the VAT of SG mice and its known importance to metabolic regulation, we utilized RNA sequencing to understand better the gene-expression profile and transcriptional networking of this depot in SG.

Table 1 outlines significant gene-level changes following SG. There was a large shift in the immunologic gene-expression profile of post-SG VAT with increased expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 8, cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein, and IgJ, corresponding to upregulation of B and T cell chemotaxis, regulation of T cell activation, and immunoglobulin crosslinking, respectively. We also observed changes in the VAT metabolic gene profile with an upregulation of EHHADH—a peroxisomal enzyme responsible for β-oxidation of fatty acids—and related processes of fatty acid β-oxidation, peroxisome function, and amino acid metabolism. In keeping with the published human data showing decreased systemic and organ-specific leptin levels following sleeve gastrectomy, there was a reduction in the leptin expression within the VAT of SG animals (7, 22, 32). There was also a reduction in oxytocin receptor signaling, which partially controls adipogenesis and fat accumulation in fat-tissue depots (71).

Next, pathway analysis was completed with the use of WikiPathways 2019. Again, there was an upregulation of immune-centric pathways, including phagocytosis, IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, chemokine signaling, and TYRO protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein signaling. The latter is associated with immune cell maturation and activation (Table 2). There were no pathways that were downregulated.

Table 2.

Upregulated, specific pathway changes identified in SG animals through functional enrichment analysis using WikiPathways 2019 Mouse

| Pathway | P Value | Combined Score |

|---|---|---|

| Chemokine signaling | 0.023 | 76.7 |

| TYROBP causal network | 0.024 | 62.0 |

| Microglia pathogen phagocytosis | 0.010 | 56.0 |

| Macrophage markers | 0.036 | 45.6 |

| IL-2 signaling | 0.001 | 45.1 |

| IL-3 signaling | 0.001 | 29.2 |

| IL-5 signaling | 0.036 | 15.7 |

Base > 50, log change > 0.5, and adjusted P < 0.05; n = 5.5. SG, sleeve gastrectomy; TYROBP, TYRO protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein.

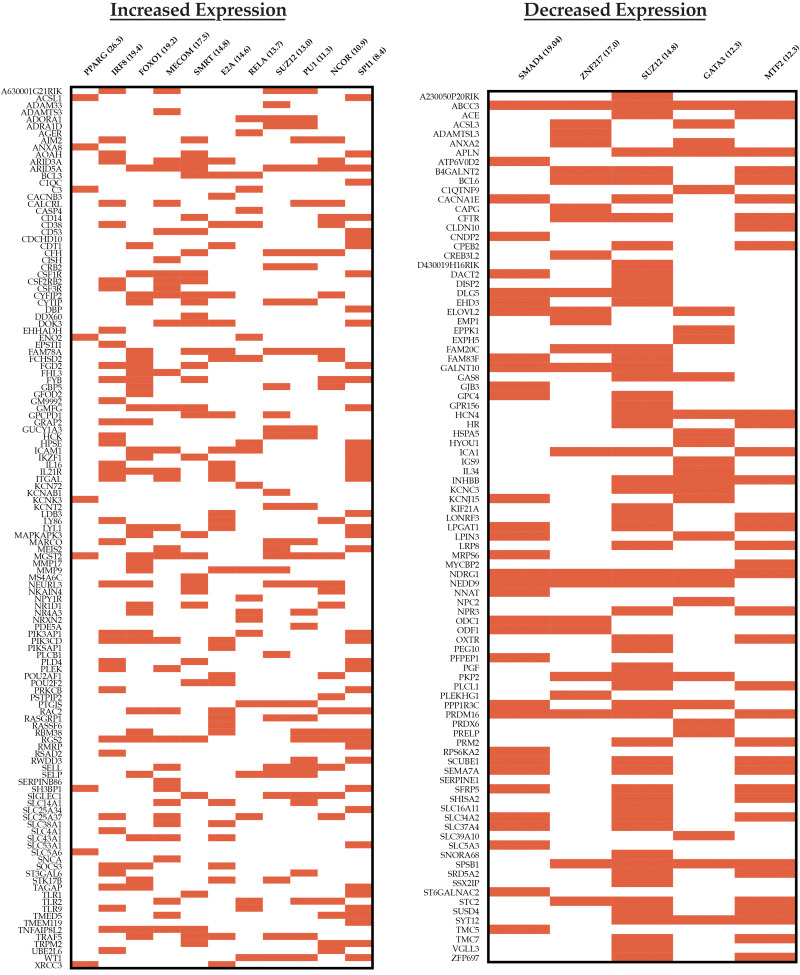

Finally, transcription factor-binding sites, upstream of theses target gene sets, were identified via ChEA2016 pathway analysis (Fig. 6). The gene-expression profile in SG VAT mapped to traditional master regulators involved in lipid and glucose homeostasis—peroxisome proliferator-activated gamma (PPARγ) and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1)—responsible for diverse processes, including glucose metabolism and adipocyte cell fate. There was contribution from a silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) and nuclear receptor corepressor (NCOR), which through subdomains, affect PPARγ signaling and modulate the immune response by transrepression of coactivators of NF-κB, IFN regulatory factors (IRFs), and LPS targets (27, 29, 42, 56). Finally, there was expression mapping to other transcription factors, such as interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8); myelodysplastic syndrome 1 and ecotropic viral integration site 1 complex locus (MECOM); polycomb-repressive complex 2 subunit (SUZ12); and E2A immunoglobulin enhancer-binding factor E12/E47 (E2A), which have roles in determining immune cell fate, cell resource utilization, and/or other metabolic processes.

Fig. 6.

ChEA2016 transcription pathway analysis showing the most upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) transcription pathways. Data are organized as clustergrams with a red bar denoting a gene contributing to the pathway expression. Only pathways with an adjusted P < 0.05 are included. Pathway titles are followed by the combined score. Base > 50, log change > 0.5, adjusted P < 0.05. E2A, E2A immunoglobulin enhancer-binding factor E12/E47; FOXO1, forkhead box protein O1; GATA3, gata-binding protein 3; IRF8, IFN regulatory factor 8; MECOM, myelodysplastic syndrome 1 and ecotropic viral integration site 1 complex locus; MTF2, metal response element-binding transcription factor 2; NCOR, nuclear receptor corepressor; PPARG, proliferator-activated receptor γ; SMRT, silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors; SUZ12, polycomb-repressive complex 2 subunit.

Transcriptional program analysis of downregulated pathways revealed a shared SUZ12 signature, suggesting that alternative expression of downstream products may be important to the global change in fat homeostasis and inflammation following SG. This is further supported by downregulation in the metal response element-binding transcription factor 2, which guides SUZ12 to specific promoters (55). Finally, there was a decrease in gata-binding protein 3 (GATA3), which is classically associated with a T helper 2 immune response but is also prevalent in adipocyte precursors. GATA3 also suppresses PPARγ, so its downregulation is in keeping with the observed increase PPARγ expression identified in the VAT of SG mice (67).

DISCUSSION

The immediate benefits of SG on glucose metabolism and insulin resistance have been documented in both human patients and mice. We have previously shown that within days of surgery, roughly 40 percent of human patients have durable improvement, or resolution, in their diabetes (33). The mechanisms behind these early, rapid changes are unclear but are critical to understanding the benefits of surgery. Our study in mice suggests that SG leads to an increase in visceral fat glucose uptake and global glucose utilization, which either drives or is the sequela of immunologic remodeling. We postulate that these processes likely underlie immediate post-SG improvements in glucose handling.

To date, most murine studies of SG have utilized a diet-induced model of obesity or a genetically obese model, combined with sham pair feeding, in an attempt to recapitulate and study SG physiology (1, 8, 20, 26, 45, 51, 59). Whereas mice in these studies become obese and have hyperglycemia similar to the target patient population, investigations are limited by differences in food intake via pair feeding and/or differences in body weight between the surgical intervention and sham groups. Furthermore, in most experiments, pair feeding induces weight loss, which can have its own profound effects.

Two studies by Kulkarni et al. (35) and Cummings et al. (17) of rats raised on standard chow have attempted to investigate the weight-independent changes of SG. Similar to our findings of increased distal delivery of 18-FDG in SG animals, Kulkarni et al. (35) showed that SG induced rapid gastric emptying, dependent on resection of the proximal stomach. The finding of increased gastric emptying is in keeping with the literature and thus likely is important in post-SG physiology (6, 12).

Cummings et al. (17) utilized a pre-diabetic rat model and showed that SG animals ate and weighed less, had improved glucose control, and had increased GLP1, GLP2, peptide YY, serum bile acids, and adiponectin.

In both of these studies, SG animals lost weight and reduced their caloric intake compared with sham animals. This poses challenges when trying to isolate weight-independent changes. Cummings et al. (17) attempted to address this by pair feeding sham animals. However, this treatment led to a reduction in energy expenditure, changes in incretin hormone production, and effects on adipocyte chemokine production in weight-matched sham animals (17).

Here, we show that the immediate weight loss-independent effects of SG can be modeled in lean, wild-type C57BL/6J mice reared on standard rodent chow. In our model, SG and sham mice have similar food-intake profiles and weight trajectory. Thus this model decouples the effects of surgery from changes in diet and body composition.

In studying the effects of biliary diversion on metabolic outcomes, Albaugh et al. (2) used a similar model of C57BL/6J mice reared on standard chow. Diverted mice in this study did not lose weight, have changes in body composition, or have changes in eating behavior. Despite this, they found improvements in glucose tolerance in diverted mice in an FXR-GLP1-dependent manner (2).

Similarly, in our model, SG and sham animals showed equivalent weight, body composition, and daily food intake without pair feeding. Despite this, SG animals had improvements in glucose homeostasis, insulin resistance, and increased circulating GLP1, all of which are hallmarks of post-SG physiology (22). Specifically, when challenged with oral glucose, SG animals showed a dramatic reduction in systemic glucose levels, 15 to 30 min postgavage, with a corollary increase in serum GLP1 expression at 15 min. This “glucose sink” phenomenon suggested increased tissue glucose uptake and utilization. In addition, this adds to the growing literature that SG, in the absence of weight loss, leads to changes in metabolic physiology (1, 26, 51).

Indirect calorimetry corroborated these findings. The RER, or the ratio of CO2 produced to O2 consumed, is a function of the substrate of cellular respiration. When an animal is predominantly using carbohydrates as a fuel source, the RER approximates 1.0, as every molecule of O2 consumed produces a single molecule of CO2. When an animal uses fatty acids as a source of respiration, the RER approaches 0.7. During a typical 24-h cycle, sham mice vacillated between 0.85 and 1.0, corresponding to fasting during the light photoperiod or feeding during the dark photoperiod, respectively. However, SG animals had a durable increase in the RER, which neared 1.0 during both light and dark cycles, indicating preferential glucose utilization during both fasting and feeding. Thus in SG mice, there appears to be an early cellular adaptation to increased glucose allocation and utilization, likely leading to long-term improvements, as shown by the continually elevated RERs in SG mice 4 wk following surgery.

Interestingly, calorimetry also revealed that SG mice had daily RER excursions above 1.0 and nearing 1.1. This phenomenon has been described previously in maximally exercising individuals as a surrogate marker for attainment of the maximum oxygen consumption and in metabolically expensive processes, such as de novo lipogenesis (DNL), owing to its reliance on the pentose phosphate pathway to produce reducing equivalents (10, 24, 65). Studies of RER in humans and mice following SG are limited. Dereppe et al. (18) have shown that human patients, following bariatric surgery, have an increase in the maximal RER attained (up to an average of 1.28) while exercising. However, SG mice in the current study do not show an increase in ambulatory activity to suggest exercise, or the equivalent, as the main driver of RER elevations.

PET/CT imaging showed increased 18-FDG uptake across all white adipose depots in SG compared with sham animals, suggesting that these depots are, in part, responsible for the glucose sink phenomenon and the elevations in RER. Importantly, this change occurred in the absence of changes in overall, fat, and lean mass and thus appears surgery specific. In contrast to Saeidi and colleagues (60), who found that intravenously delivered 18-FDG was sequestered to the alimentary roux limb of rats following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, we found no difference in bowel-specific glucose uptake in SG animals. These differences may be related to the route of 18-FDG administration. However, owing to the importance of incretin hormones in post-SG outcomes, we felt that orally administered glucose was more physiologically relevant. These differences highlight that whereas these two procedures may result in clinically and physiologically similar outcomes, they may differ in how those outcomes are achieved. However, it is unclear whether changes at the level of the intestine, such as FXR and G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 agonism, as shown by others, are responsible for increased glucose uptake in VAT (2, 17, 20, 45).

Based on these findings, we explored VAT gene-level changes in SG mice. This revealed an upregulation in multiple metabolic processes that potentially indicate increased lipolysis, increased de novo lipogenesis, and modulated adipocyte cell fate. For example, upregulation in FOXO1 pathways and the gene EHHADH indicates increased lipolysis and β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids, respectively (30, 52). SG animals also had an upregulation in MECOM-regulated pathways, which are associated with increased purine and pyrimidine metabolism, amino acid metabolism, pentose phosphate pathway reliance, and glycolysis (25). Elevations in PPARγ, SMRT, and NCOR, which all interact to control downstream adipocyte fate and function, glucose handling, insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and thermogenesis, were also found (14, 28, 29, 40, 56, 65, 69, 75). Thus as inferred from the calorimetry data, there is upregulation of transcriptional machinery capable of increasing energy production and glucose utilization within the VAT of SG mice.

Unexpectedly, SG mice had an upregulation in multiple immune processes within the VAT. Most of the isolated, gene-level changes occurred in pathways for myeloid and B cell chemotaxis and differentiation. Increased levels of CXCL13 and IgJ suggest B cell chemotaxis to SG VAT and increased immunoglobulin production and crosslinking. Upregulation of transcription factors, outlined in Fig. 6, are likely underlying these changes (4). These again include NCOR and SMRT, which both coordinate to modulate the immune response through NF-κB, IRFs, and LPS target genes and reduce the proinflammatory phenotype of macrophages (27, 42). We also identified a robust signal in IRF8, which is associated with innate and adaptive immune responses and adipocyte metabolic regulation (57, 64, 74), and SUZ12, which has been shown to be a regulator of energy metabolism through modulation of brown fat thermogenesis (36, 39).

Taken as a whole, these data suggest that there is a complex interaction between the metabolic activity of the VAT and the local immune cell fraction in SG animals. However, given both the metabolic and immune gene profiling outlined above, it is unclear if local adipocyte function is driving immune changes or if there is immunologic remodeling leading to increased glucose sequestration and utilization.

As outlined by Solinas and colleagues (65) and others (23, 72), adipocyte processes, like DNL, are capable of driving both local and global metabolic and immune function via PPAR signaling and affecting GLP1 secretion, hepatic lipogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and the host gut barrier and immunity. Alternatively, it is plausible that local immune remodeling is driving metabolism. Immune cell trafficking, activation, differentiation, and retention are all metabolically demanding. When activated, T cells change from a quiescent state, reliant on basal oxidative phosphorylation, to a highly anabolic state with increased mitochondrial production, as well as increased contributions of the pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis, and glutaminolysis to energy production (5, 19). This increased demand for reducing equivalents may alter the glucose uptake of the VAT depot and drive the RER in the direction of CO2 production (i.e., above 1.0). Similarly, macrophage, T cell, and B cell polarization and production of tolerance within dendritic cells can have profound effects upon metabolism (37, 44, 46, 53). Finally, we have previously shown in rats that SG induces reductions in jejunal expression of IL-17, IL-23, and interferon-γ, which are correlated with weight loss and systemic insulin levels in SG animals (66).

Thus it is plausible that VAT-specific changes underlie the SG-related improvements in glucose handling by increasing metabolically demanding local processes, which in turn affect global metabolism. In fact, studies of caloric restriction have shown that feeding can induce adipose tissue DNL, increase RER above 1.0, and lead to innate immune modulation (10, 70).

Limitations.

Our study was completed in C57BL/6J mice fed normal rodent chow. Li et al. (41) showed that SG animals in a diet-induced model of obesity decreased the average RER toward 0.7. These differences can be partially explained by the available dietary resources in the experiment and may indicate that SG mice, when exposed to excess fat calories, adaptively increase β-oxidation. Furthermore, in their experiment, calorimetry was performed at 7 wk postoperatively, and thus it is possible that they missed the weight loss-independent effects that occur early in the postsurgical time course and that our finding of increased RER may become extinct as physiologic adaptation to postsurgical changes occurs. The latter is in keeping with the clinical reality that the main physiologic driver of diabetes remission occurs within days of surgery and that further improvements may occur with weight loss (31, 33, 61, 62). Finally, given the nature of our model, we were not able to explore the weight-dependent effects of SG.

Conclusions.

SG induces immediate and durable weight loss-independent increases in glucose utilization heralded by enhanced metabolic activity of and local immunologic remodeling of VAT. Future studies should be aimed at better understanding the interplay of host immunity and adipocyte biology to post-SG physiology.

GRANTS

This work was conducted with the support of two funding sources from the senior author and one from the first author. First, was an appointed KL2 award from Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award KL2 TR002542). Second, funding was obtained through a Pilot Grant from the Boston Area Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (BADERC; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, P30 DK057521). Finally, the American College of Surgeons also provided a 2-yr competitive research scholarship.

DISCLOSURES

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.A.H., R.S., A.S.B., A.T., and E.G.S. conceived and designed research; D.A.H., A.M., D.C., K.H., and R.S. performed experiments; D.A.H., A.M., D.C., and K.H. analyzed data; D.A.H., A.M., D.C., K.H., R.S., A.S.B., A.T., and E.G.S. interpreted results of experiments; D.A.H. prepared figures; D.A.H. drafted manuscript; D.A.H., K.H., R.S., A.S.B., A.T., and E.G.S. edited and revised manuscript; D.A.H., A.M., D.C., K.H., R.S., A.S.B., A.T., and E.G.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Gazala S, Horwitz E, Ben-Haroush Schyr R, Bardugo A, Israeli H, Hija A, Schug J, Shin S, Dor Y, Kaestner KH, Ben-Zvi D. Sleeve gastrectomy improves glycemia independent of weight loss by restoring hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 67: 1079–1085, 2018. doi: 10.2337/db17-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albaugh VL, Banan B, Antoun J, Xiong Y, Guo Y, Ping J, Alikhan M, Clements BA, Abumrad NN, Flynn CR. Role of bile acids and GLP-1 in mediating the metabolic improvements of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterology 156: 1041–1051.e4, 2019. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arble DM, Sandoval DA, Seeley RJ. Mechanisms underlying weight loss and metabolic improvements in rodent models of bariatric surgery. Diabetologia 58: 211–220, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayoub E, Wilson MP, McGrath KE, Li AJ, Frisch BJ, Palis J, Calvi LM, Zhang Y, Perkins AS. EVI1 overexpression reprograms hematopoiesis via upregulation of Spi1 transcription. Nat Commun 9: 4239, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06208-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baixauli F, Acín-Pérez R, Villarroya-Beltrí C, Mazzeo C, Nuñez-Andrade N, Gabandé-Rodriguez E, Ledesma MD, Blázquez A, Martin MA, Falcón-Pérez JM, Redondo JM, Enríquez JA, Mittelbrunn M. Mitochondrial respiration controls lysosomal function during inflammatory T cell responses. Cell Metab 22: 485–498, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann T, Kuesters S, Grueneberger J, Marjanovic G, Zimmermann L, Schaefer AO, Hopt UT, Langer M, Karcz WK. Time-resolved MRI after ingestion of liquids reveals motility changes after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—preliminary results. Obes Surg 21: 95–101, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belgaumkar AP, Vincent RP, Carswell KA, Hughes RD, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Mitry RR, le Roux CW, Patel AG. Changes in bile acid profile after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy are associated with improvements in metabolic profile and fatty liver disease. Obes Surg 26: 1195–1202, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Zvi D, Meoli L, Abidi WM, Nestoridi E, Panciotti C, Castillo E, Pizarro P, Shirley E, Gourash WF, Thompson CC, Munoz R, Clish CB, Anafi RC, Courcoulas AP, Stylopoulos N. Time-dependent molecular responses differ between gastric bypass and dieting but are conserved across species. Cell Metab 28: 310–323.e6, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braghetto I, Davanzo C, Korn O, Csendes A, Valladares H, Herrera E, Gonzalez P, Papapietro K. Scintigraphic evaluation of gastric emptying in obese patients submitted to sleeve gastrectomy compared to normal subjects. Obes Surg 19: 1515–1521, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruss MD, Khambatta CF, Ruby MA, Aggarwal I, Hellerstein MK. Calorie restriction increases fatty acid synthesis and whole body fat oxidation rates. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E108–E116, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00524.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavin J-B, Bado A, Le Gall M. Intestinal adaptations after bariatric surgery: consequences on glucose homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 28: 354–364, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers AP, Smith EP, Begg DP, Grayson BE, Sisley S, Greer T, Sorrell J, Lemmen L, LaSance K, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, D’Alessio DA, Sandoval DA. Regulation of gastric emptying rate and its role in nutrient-induced GLP-1 secretion in rats after vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E424–E432, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00469.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, Clark NR, Ma’ayan A. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 14: 128, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhary AK, Dey CS. Nuclear co-repressor (NCoR) is required to maintain insulin sensitivity in C2C12 myotubes. Cell Biol Int 41: 204–212, 2017. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chusyd DE, Wang D, Huffman DM, Nagy TR. Relationships between rodent white adipose fat pads and human white adipose fat depots. Front Nutr 3: 10, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2016.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornwell M, Vangala M, Taing L, Herbert Z, Köster J, Li B, Sun H, Li T, Zhang J, Qiu X, Pun M, Jeselsohn R, Brown M, Liu XS, Long HW. VIPER: Visualization Pipeline for RNA-seq, a Snakemake workflow for efficient and complete RNA-seq analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 19: 135, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings BP, Bettaieb A, Graham JL, Stanhope KL, Kowala M, Haj FG, Chouinard ML, Havel PJ. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy improves glucose and lipid metabolism and delays diabetes onset in UCD-T2DM rats. Endocrinology 153: 3620–3632, 2012. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dereppe H, Forton K, Pauwen NY, Faoro V. Impact of bariatric surgery on women aerobic exercise capacity. Obes Surg 29: 3316–3323, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desdín-Micó G, Soto-Heredero G, Mittelbrunn M. Mitochondrial activity in T cells. Mitochondrion 41: 51–57, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding L, Sousa KM, Jin L, Dong B, Kim B-W, Ramirez R, Xiao Z, Gu Y, Yang Q, Wang J, Yu D, Pigazzi A, Schones D, Yang L, Moore D, Wang Z, Huang W. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy activates GPBAR-1/TGR5 to sustain weight loss, improve fatty liver, and remit insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 64: 760–773, 2016. doi: 10.1002/hep.28689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21, 2013. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du J, Hu C, Bai J, Peng M, Wang Q, Zhao N, Wang Y, Wang G, Tao K, Wang G, Xia Z. Intestinal glucose absorption was reduced by vertical sleeve gastrectomy via decreased gastric leptin secretion. Obes Surg 28: 3851–3861, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dufort FJ, Gumina MR, Ta NL, Tao Y, Heyse SA, Scott DA, Richardson AD, Seyfried TN, Chiles TC. Glucose-dependent de novo lipogenesis in B lymphocytes: a requirement for ATP-citrate lyase in lipopolysaccharide-induced differentiation. J Biol Chem 289: 7011–7024, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.551051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan GE, Howley ET, Johnson BN. Applicability of VO2max criteria: discontinuous versus continuous protocols. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29: 273–278, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199702000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenouille N, Bassil CF, Ben-Sahra I, Benajiba L, Alexe G, Ramos A, Pikman Y, Conway AS, Burgess MR, Li Q, Luciano F, Auberger P, Galinsky I, DeAngelo DJ, Stone RM, Zhang Y, Perkins AS, Shannon K, Hemann MT, Puissant A, Stegmaier K. The creatine kinase pathway is a metabolic vulnerability in EVI1-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med 23: 301–313, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nm.4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frikke-Schmidt H, Zamarron BF, O’Rourke RW, Sandoval DA, Lumeng CN, Seeley RJ. Weight loss independent changes in adipose tissue macrophage and T cell populations after sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Mol Metab 6: 317–326, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghisletti S, Huang W, Jepsen K, Benner C, Hardiman G, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. Cooperative NCoR/SMRT interactions establish a corepressor-based strategy for integration of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Genes Dev 23: 681–693, 2009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1773109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodson ML, Young BM, Snyder CA, Schroeder AC, Privalsky ML. Alteration of NCoR corepressor splicing in mice causes increased body weight and hepatosteatosis without glucose intolerance. Mol Cell Biol 34: 4104–4114, 2014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00554-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo C, Li Y, Gow C-H, Wong M, Zha J, Yan C, Liu H, Wang Y, Burris TP, Zhang J. The optimal corepressor function of nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ requires G protein pathway suppressor 2. J Biol Chem 290: 3666–3679, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houten SM, Denis S, Argmann CA, Jia Y, Ferdinandusse S, Reddy JK, Wanders RJA. Peroxisomal L-bifunctional enzyme (Ehhadh) is essential for the production of medium-chain dicarboxylic acids. J Lipid Res 53: 1296–1303, 2012. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M024463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Helmrath MA, Brandt ML, Harmon CM, Zeller MH, Chen MK, Xanthakos SA, Horlick M, Buncher CR; Teen-LABS Consortium . Weight loss and health status 3 years after bariatric surgery in adolescents. N Engl J Med 374: 113–123, 2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalinowski P, Paluszkiewicz R, Wróblewski T, Remiszewski P, Grodzicki M, Bartoszewicz Z, Krawczyk M. Ghrelin, leptin, and glycemic control after sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass—results of a randomized clinical trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13: 181–188, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heshmati K, Harris DA, Aliakbarian H, Tavakkoli A, Sheu EG. Comparison of early type 2 diabetes improvement after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: medication cessation at discharge predicts 1-year outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis 15: 2025–2032, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A, McDermott MG, Monteiro CD, Gundersen GW, Ma’ayan A. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 44: W90–W97, 2016. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulkarni BV, LaSance K, Sorrell JE, Lemen L, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Sandoval D. The role of proximal versus distal stomach resection in the weight loss seen after vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R979–R987, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00125.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SC, Miller S, Hyland C, Kauppi M, Lebois M, Di Rago L, Metcalf D, Kinkel SA, Josefsson EC, Blewitt ME, Majewski IJ, Alexander WS. Polycomb repressive complex 2 component Suz12 is required for hematopoietic stem cell function and lymphopoiesis. Blood 126: 167–175, 2015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YS, Wollam J, Olefsky JM. An integrated view of immunometabolism. Cell 172: 22–40, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med 332: 621–628, 1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li F, Wu R, Cui X, Zha L, Yu L, Shi H, Xue B. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) negatively regulates thermogenic program in brown adipocytes via coordinated regulation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) deacetylation and methylation. J Biol Chem 291: 4523–4536, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li P, Fan W, Xu J, Lu M, Yamamoto H, Auwerx J, Sears DD, Talukdar S, Oh D, Chen A, Bandyopadhyay G, Scadeng M, Ofrecio JM, Nalbandian S, Olefsky JM. Adipocyte NCoR knockout decreases PPARγ phosphorylation and enhances PPARγ activity and insulin sensitivity. Cell 147: 815–826, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li P, Rao Z, Laing B, Bunner WP, Landry T, Prete A, Yuan Y, Zhang ZT, Huang H. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy improves liver and hypothalamic functions in obese mice. J Endocrinol 241: 135–147, 2019. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li P, Spann NJ, Kaikkonen MU, Lu M, Oh DY, Fox JN, Bandyopadhyay G, Talukdar S, Xu J, Lagakos WS, Patsouris D, Armando A, Quehenberger O, Dennis EA, Watkins SM, Auwerx J, Glass CK, Olefsky JM. NCoR repression of LXRs restricts macrophage biosynthesis of insulin-sensitizing omega 3 fatty acids. Cell 155: 200–214, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malinarich F, Duan K, Hamid RA, Bijin A, Lin WX, Poidinger M, Fairhurst AM, Connolly JE. High mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic capacity represent a metabolic phenotype of human tolerogenic dendritic cells. J Immunol 194: 5174–5186, 2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGavigan AK, Garibay D, Henseler ZM, Chen J, Bettaieb A, Haj FG, Ley RE, Chouinard ML, Cummings BP. TGR5 contributes to glucoregulatory improvements after vertical sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Gut 66: 226–234, 2017. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin T, Ackerman SE, Shen L, Engleman E. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in obesity-associated metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 127: 5–13, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI88876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melissas J, Koukouraki S, Askoxylakis J, Stathaki M, Daskalakis M, Perisinakis K, Karkavitsas N. Sleeve gastrectomy: a restrictive procedure? Obes Surg 17: 57–62, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mina AI, LeClair RA, LeClair KB, Cohen DE, Lantier L, Banks AS. CalR: a web-based analysis tool for indirect calorimetry experiments. Cell Metab 28: 656–666.e1, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, Nanni G, Pomp A, Castagneto M, Ghirlanda G, Rubino F. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 366: 1577–1585, 2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mithieux G, Gautier-Stein A. Intestinal glucose metabolism revisited. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 105: 295–301, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Myronovych A, Kirby M, Ryan KK, Zhang W, Jha P, Setchell KD, Dexheimer PJ, Aronow B, Seeley RJ, Kohli R. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy reduces hepatic steatosis while increasing serum bile acids in a weight-loss-independent manner. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22: 390–400, 2014. doi: 10.1002/oby.20548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakae J, Cao Y, Oki M, Orba Y, Sawa H, Kiyonari H, Iskandar K, Suga K, Lombes M, Hayashi Y. Forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 in adipose tissue regulates energy storage and expenditure. Diabetes 57: 563–576, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Takaki S, Nagasaki M, Otsu M, Yamashita H, Sugita J, Yoshimura K, Eto K, Komuro I, Kadowaki T, Nagai R. Adipose natural regulatory B cells negatively control adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab 18: 759–766, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pal A, Rhoads DB, Tavakkoli A. Foregut exclusion disrupts intestinal glucose sensing and alters portal nutrient and hormonal milieu. Diabetes 64: 1941–1950, 2015. doi: 10.2337/db14-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perino M, van Mierlo G, Karemaker ID, van Genesen S, Vermeulen M, Marks H, van Heeringen SJ, Veenstra GJC. MTF2 recruits polycomb repressive complex 2 by helical-shape-selective DNA binding. Nat Genet 50: 1002–1010, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reilly SM, Bhargava P, Liu S, Gangl MR, Gorgun C, Nofsinger RR, Evans RM, Qi L, Hu FB, Lee CH. Nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT regulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mediates aging-related metabolic deterioration. Cell Metab 12: 643–653, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers JH, Owens KS, Kurkewich J, Klopfenstein N, Iyer SR, Simon MC, Dahl R. E2A antagonizes PU.1 activity through inhibition of DNA binding. BioMed Res Int 2016: 3983686–11, 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/3983686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. Effect of chronic food restriction on energy balance, thermogenic capacity, and brown-adipose-tissue activity in the rat. Biosci Rep 2: 543–549, 1982. doi: 10.1007/BF01314214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, Wilson-Pérez HE, Sandoval DA, Kohli R, Bäckhed F, Seeley RJ. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature 509: 183–188, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saeidi N, Meoli L, Nestoridi E, Gupta NK, Kvas S, Kucharczyk J, Bonab AA, Fischman AJ, Yarmush ML, Stylopoulos N. Reprogramming of intestinal glucose metabolism and glycemic control in rats after gastric bypass. Science 341: 406–410, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 376: 641–651, 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Aminian A, Pothier CE, Kim ESH, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 370: 2002–2013, 2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Segal-Lieberman G, Segal P, Dicker D. Revisiting the role of BMI in the guidelines for bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care 39, Suppl 2: S268–S273, 2016. doi: 10.2337/dcS15-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw LA, Bélanger S, Omilusik KD, Cho S, Scott-Browne JP, Nance JP, Goulding J, Lasorella A, Lu LF, Crotty S, Goldrath AW. Id2 reinforces TH1 differentiation and inhibits E2A to repress TFH differentiation. Nat Immunol 17: 834–843, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Solinas G, Borén J, Dulloo AG. De novo lipogenesis in metabolic homeostasis: more friend than foe? Mol Metab 4: 367–377, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Subramaniam R, Aliakbarian H, Bhutta HY, Harris DA, Tavakkoli A, Sheu EG. Sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass attenuate pro-inflammatory small intestinal cytokine signatures. Obes Surg 29: 3824–3832, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tong Q, Dalgin G, Xu H, Ting CN, Leiden JM, Hotamisligil GS. Function of GATA transcription factors in preadipocyte-adipocyte transition. Science 290: 134–138, 2000. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28: 511–515, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Witte N, Muenzner M, Rietscher J, Knauer M, Heidenreich S, Nuotio-Antar AM, Graef FA, Fedders R, Tolkachov A, Goehring I, Schupp M. The glucose sensor ChREBP links de novo lipogenesis to PPARγ activity and adipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology 156: 4008–4019, 2015. doi: 10.1210/EN.2015-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu Z, Isik M, Moroz N, Steinbaugh MJ, Zhang P, Blackwell TK. Dietary restriction extends lifespan through metabolic regulation of innate immunity. Cell Metab 29: 1192–1205.e8, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yi KJ, So KH, Hata Y, Suzuki Y, Kato D, Watanabe K, Aso H, Kasahara Y, Nishimori K, Chen C, Katoh K, Roh SG. The regulation of oxytocin receptor gene expression during adipogenesis. J Neuroendocrinol 27: 335–342, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jne.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yilmaz M, Claiborn KC, Hotamisligil GS. De novo lipogenesis products and endogenous lipokines. Diabetes 65: 1800–1807, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db16-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yska JP, van Roon EN, de Boer A, Leufkens HG, Wilffert B, de Heide LJ, de Vries F, Lalmohamed A. Remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients after different types of bariatric surgery: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. JAMA Surg 150: 1126–1133, 2015. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao GN, Jiang DS, Li H. Interferon regulatory factors: at the crossroads of immunity, metabolism, and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852: 365–378, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhuang Q, Li W, Benda C, Huang Z, Ahmed T, Liu P, Guo X, Ibañez DP, Luo Z, Zhang M, Abdul MM, Yang Z, Yang J, Huang Y, Zhang H, Huang D, Zhou J, Zhong X, Zhu X, Fu X, Fan W, Liu Y, Xu Y, Ward C, Khan MJ, Kanwal S, Mirza B, Tortorella MD, Tse HF, Chen J, Qin B, Bao X, Gao S, Hutchins AP, Esteban MA. NCoR/SMRT co-repressors cooperate with c-MYC to create an epigenetic barrier to somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol 20: 400–412, 2018. [Erratum in Nat Cell Biol 20: 1227, 2018]. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]