Significance

The development of a universal influenza vaccine is a major public health need globally, and identifying the optimal formulation will be an important first step for developing such a vaccine. Here we show that a two-dose immunization of humans with an inactivated, AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 avian influenza virus vaccine engaged both the preexisting memory and naive B cell compartments. Importantly, we show that the recruited memory B cells after first immunization were directed against conserved epitopes within the H5 HA stem region while the responses after the second immunization were mostly directed against strain-specific epitopes within the HA globular head. Taken together these findings have broad implications toward optimizing vaccination strategies for developing more effective vaccines against pandemic viruses.

Keywords: influenza, memory, H5N1, adjuvant, B cells

Abstract

There is a need for improved influenza vaccines. In this study we compared the antibody responses in humans after vaccination with an AS03-adjuvanted versus nonadjuvanted H5N1 avian influenza virus inactivated vaccine. Healthy young adults received two doses of either formulation 3 wk apart. We found that AS03 significantly enhanced H5 hemagglutinin (HA)-specific plasmablast and antibody responses compared to the nonadjuvanted vaccine. Plasmablast response after the first immunization was exclusively directed to the conserved HA stem region and came from memory B cells. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) derived from these plasmablasts had high levels of somatic hypermutation (SHM) and recognized the HA stem region of multiple influenza virus subtypes. Second immunization induced a plasmablast response to the highly variable HA head region. mAbs derived from these plasmablasts exhibited minimal SHM (naive B cell origin) and largely recognized the HA head region of the immunizing H5N1 strain. Interestingly, the antibody response to H5 HA stem region was much lower after the second immunization, and this suppression was most likely due to blocking of these epitopes by stem-specific antibodies induced by the first immunization. Taken together, these findings show that an adjuvanted influenza vaccine can substantially increase antibody responses in humans by effectively recruiting preexisting memory B cells as well as naive B cells into the response. In addition, we show that high levels of preexisting antibody can have a negative effect on boosting. These findings have implications toward the development of a universal influenza vaccine.

Influenza virus antigenic variation poses a major challenge to the development of an effective influenza vaccine (1–6). In addition, the occasional spillover of influenza A viruses from animal reservoirs into the human population can result in more serious outbreaks, as seen with the avian H5N1 and H7N9 viruses (7, 8). Inactivated influenza virus vaccines predominantly elicit antibody responses to the major surface glycoprotein of the virus, the hemagglutinin (HA) (6, 9). Several studies have shown that antibody levels against the HA correlate with protection against influenza virus infection in humans (1, 10, 11). Antibody responses to the influenza HA protein can be broadly categorized into strain-specific antibodies binding only to the homologous HA and cross-reactive antibodies binding broadly to multiple HA subtypes (12, 13). Strain-specific antibodies primarily target epitopes within HA globular head while most of the broadly reactive antibodies, with a few notable exceptions, bind to the conserved stem region of HA (3). These two categories of antibodies display critical differences in their ability to neutralize the virus in vitro and to protect against virus infection in vivo. Given that eliciting broadly reactive antibodies is critical for the development of a universal influenza virus vaccine, it is important to understand the factors that control which of the two types of antibody responses dominate following influenza virus vaccination (14–16).

Several studies have shown that adjuvants can enhance the magnitude and breadth of antibody responses after influenza vaccination of humans (17–24). However, it was not clearly defined whether in these studies the adjuvants mostly enhanced the expansion and differentiation of preexisting memory B cells (MBCs) or if the adjuvants also increased the recruitment of naive B cells into the response. It is also important to examine how adjuvants impact the relative increase in the levels of HA head versus HA stem antibody responses after vaccination. In this study we have addressed these questions by comparing human antibody responses to vaccination with a nonadjuvanted inactivated H5N1 vaccine versus the same H5N1 vaccine adjuvanted with AS03, an oil in water emulsion-based adjuvant composed of squalene, polysorbate 80, and α-tocopherol (Vitamin E) (19, 23, 25).

Results

AS03 Adjuvant Enhances the Plasmablast and Antibody Response to H5N1 Vaccination.

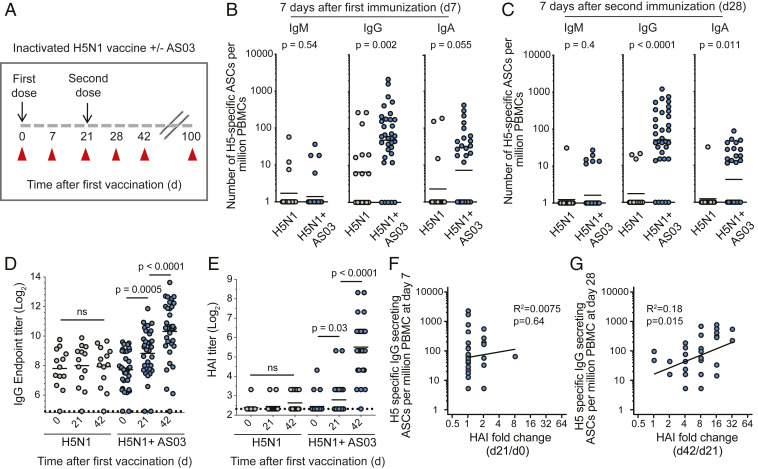

We conducted a vaccination study to determine the effect of AS03 adjuvant on B cell responses to inactivated H5N1 influenza vaccination in humans. A total of 50 healthy young adults were recruited and received an intramuscular injection of the monovalent split-virion A/Indonesia/5/2005 (H5N1) vaccine in conjunction with (n = 33) or without (n = 17) the AS03 adjuvant. Immunizations were given on days 0 and 21, and blood specimens were collected at days 0, 7, 21, 28, 42, and 100 after the first vaccination (Fig. 1A). H5 HA-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA-secreting plasmablasts were measured at the peak of the plasmablast responses on days 7 and 28 after vaccination (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). IgM-secreting plasmablasts directed against H5 HA were present at lower frequencies than IgG- and IgA-secreting cells at day 7 after each immunization (Fig. 1 B and C). The IgG-secreting plasmablast frequencies were greater in the adjuvanted group compared to the nonadjuvanted group 7 d after the first and second immunizations (P = 0.002 and <0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1 B and C). The frequencies of IgA-secreting cells were also greater in the adjuvanted group after both immunizations (Fig. 1 B and C). Thus, the AS03 adjuvant substantially increases the plasmablast response induced after H5N1 vaccination in humans.

Fig. 1.

AS03 enhances the plasmablast response to H5N1 vaccination in humans. (A) Study design: 50 healthy young adults (21–45 y old) were immunized twice (3 wk apart) with an inactivated monovalent H5N1 vaccine (A/Indonesia/5/20015) either adjuvanted with AS03 (n = 33) or nonadjuvanted (n = 17). Blood samples were collected at days 0, 7, 21, 28, 42, and 100 after first vaccination. (B and C) Mean frequencies of H5 HA-specific IgM-, IgG-, and IgA-secreting plasmablasts (per million peripheral blood mononuclear cells or PBMCs) were measured at days 7 (B) and 28 (C) after first vaccination by ELISpot. y axis labels for the three isotypes are indicated on the leftmost panel. (D) Serum IgG endpoint titers against H5 HA measured at days 0, 21, and 42 after first immunization in adjuvanted and nonadjuvanted groups. (E) Serum HAI antibody titers measured at days 0, 21, and 42 after first immunization in adjuvanted and nonadjuvanted groups. (F and G) Correlation between the frequency of H5-specific plasmablast response at days 7 (F) and 28 (G) with the increase in serum HAI titers from days 0 to 21 and from days 21 to 42, respectively. P values are the results of Mann–Whitney u test (B and C) and unpaired t tests (D and E). ns, not significant; ASCs, antibody secreting cells.

Consistent with the poor plasmablast response we did not observe any increase in serum anti-H5 HA IgG titers either after the first or the booster immunization with the nonadjuvanted vaccine (Fig. 1D). In contrast, there was a significant increase in H5-specific IgG antibody titers in the adjuvanted cohort after the first (P = 0.0005) and second immunizations (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1D). We next examined the capacity of serum anti-H5 antibodies to block viral-mediated hemagglutination. Again, we did not observe any significant increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) serum antibody titers after vaccination compared to prevaccination levels in the nonadjuvanted cohort (Fig. 1E). In contrast, we observed a modest 1.5-fold increase in HAI titers after the first vaccination and an 8-fold increase in HAI titers above day 21 values after the booster immunization in the adjuvanted cohort (Fig. 1E). It has been previously shown that the day 7 plasmablast response correlates with the fold increase in serum HAI titers after influenza vaccination in humans (26). We did not see any significant correlation between the plasmablast response after first immunization and the modest increase in HAI titers between days 0 and 21 (Fig. 1F). Instead, we observed a significant correlation between the plasmablast response after the second immunization and the increase in HAI titers between days 21 and 42 (Fig. 1G). Overall, these serological data corroborate the plasmablast results showing the superiority of the adjuvanted vaccine formulation in inducing vaccine-specific plasmablast and antibody responses. However, it is also worth noting that while the magnitude of the plasmablast response after the first and second immunization in the adjuvanted cohort is comparable, the exact specificity of the antibody could be different since the HAI titers only showed a substantial increase after the booster immunization at day 21.

AS03 Enhances H5 Stem- and H5 Head-Specific Antibody Responses in a Biphasic Manner.

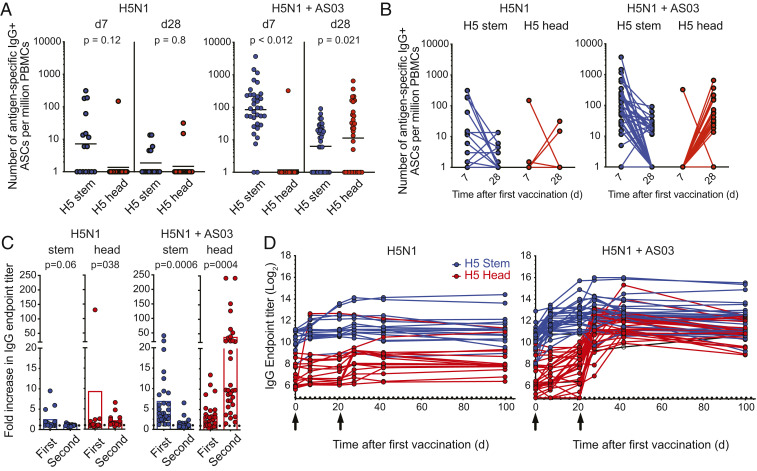

Given the discrepancy in HAI responses after first and second immunizations, we wanted to dissect the domains within the H5 HA targeted by the plasmablast response. We expressed the H5 trimeric globular head or chimeric HA molecules that express the globular head of H9 HA (to which humans are mostly naive) and the stem region of H5 to measure the frequency of H5 head- and stem-specific responses, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). H5 stem-specific, IgG-secreting plasmablasts dominated the response at day 7 after H5N1 vaccination (Fig. 2 A and B). This result was observed in the case of subjects who received the nonadjuvanted vaccine and to a much greater extent in those who received the AS03-adjuvanted formulation (Fig. 2 A and B). A reversed scenario was observed at day 28, where H5 HA head-specific IgG-secreting plasmablasts were dominant (Fig. 2 A and B). H5 head-specific plasmablasts in the nonadjuvanted group were largely below the detection limit, highlighting the dependence of this response on the adjuvant. IgA-secreting plasmablast response showed a similar trend to the IgG counterpart (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Human B cell and serum antibody response to H5 HA head and stem regions after H5N1 vaccination. (A and B) The mean frequencies of IgG-secreting plasmablasts isolated from donors immunized with the nonadjuvanted inactivated H5N1 vaccine (Left) or the AS03-adjuvanted vaccine (Right). H5N1 vaccination-induced plasmablasts that are either directed against the H5 HA stem region (blue) or head region (red) as determined by ELISpot are shown. (C) Fold change in serum IgG titers that are directed against H5 stem region (blue, Left) and H5 head region (red, Middle) as determined by ELISA. Increase in IgG endpoint titers is represented as a fold change after first immunization from days 0 to 21. Fold change after second immunization was similarly calculated using the day 21 and 42 titers. y axis labels are indicated on the leftmost panel. (D) Longitudinal analysis of serum IgG endpoint titers that are directed either against H5 HA stem (blue) or head (red) regions. P values are the results of unpaired t tests. ASCs, antibody secreting cells.

We next examined serum IgG responses to the H5 HA head and stem regions after the first and second immunizations. No significant increases in serum anti-H5 HA head or stem antibodies after nonadjuvanted H5N1 vaccination were observed (Fig. 2 C, Left). With the AS03-adjuvanted formulation, anti-H5 HA stem IgG antibodies showed a 7-fold increase between days 0 and 21 after the first vaccination, but only a 1.2-fold change after the booster immunization (between days 21 and 42) (Fig. 2 C, Right). On the other hand, anti-H5 head antibodies showed a modest (3-fold) increase after the first immunization and a significantly larger 38-fold increase after the second immunization (Fig. 2 C, Right). Longitudinal tracking of serum IgG titers directed against the H5 stem and H5 head regions showed that stem-specific responses peaked earlier (1–3 wk after first vaccination) than those specific to the H5 head (4–6 wk after first vaccination) (Fig. 2D). The increase in serum anti-H5 stem IgG titers between days 0 and 21 significantly correlated with the frequency of day 7 anti-H5 HA stem plasmablasts (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), whereas the increase in anti-H5 head serum titers between days 21 and 42 correlated with the day 28 anti-H5 HA head plasmablast responses (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).

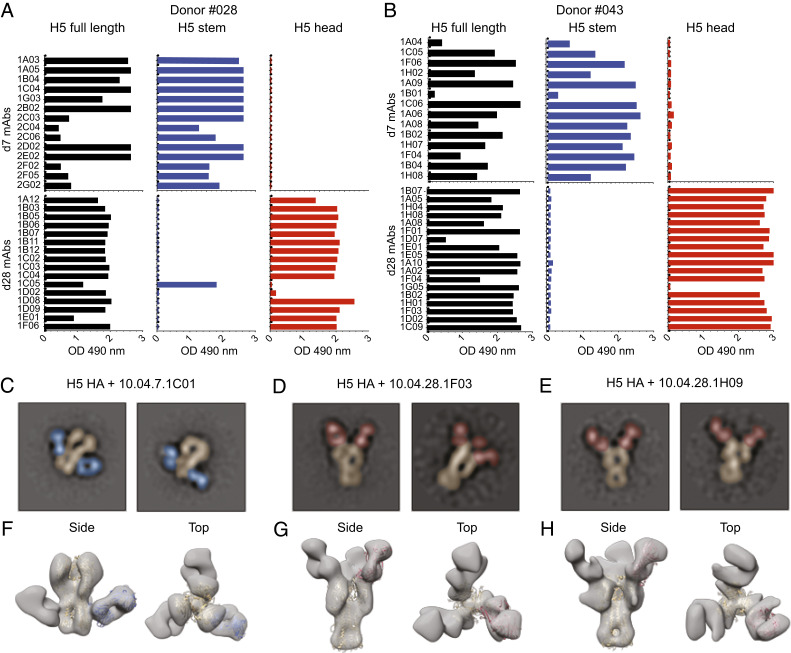

Plasmablast-Derived Recombinant Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) Recapitulate the Biphasic Response to H5 Stem versus H5 Head after H5N1 Vaccination.

We single-cell sorted plasmablasts isolated at days 7 and 28 after first vaccination from four subjects (#04, #028, #036, and #043) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) who received the adjuvanted vaccine formulation. These plasmablasts were sorted based on surface phenotype or using a fluorescently labeled recombinant full-length H5 HA probe that encompasses the head and stem regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Recombinant human mAbs from single cells were generated as previously described (27). The specificity of the generated mAbs were consistent with the plasmablast data; 100% (38/38) of the day 7 plasmablast-derived H5-specific mAbs were directed against the H5 stem region, and the vast majority (93%, 41/43) of those derived from day 28 plasmablasts were directed against the H5 head region (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). We confirmed the ELISA binding data by negative stain electron microscopy two-dimensional (2D) class averages of H5 HA (A/Indonesia/05/2005) in complex with the fraction antigen-binding (Fabs) of three of the mAbs (10.04.7.1C01, 10.04.28.1F03, and 10.04.28.1H09) (Fig. 3 C–H). These data show that the antibody response to adjuvanted prime and booster H5N1 vaccination in humans follows a biphasic pattern; the first wave of the response is primarily directed against the conserved stem region while the second wave is primarily directed against the more variable head region.

Fig. 3.

Human H5N1 vaccination-induced anti-H5 HA monoclonal antibodies. (A and B) ELISA binding of recombinant human mAbs derived from two donors’ plasmablasts isolated at day 7 after vaccination (H5 stem) or at day 28 after first vaccination (H5 head). Each row represents a mAb, and shown is the ELISA optical density (OD 450 nm) of each mAb-binding assay against H5 HA (black), H5 stem region (blue), and H5 head region (red). (C–E) Negative stain electron microscopy 2D class averages of H5 HA (A/Indonesia/05/2005, false-colored in gold) in complex with donor #04 day 7 Fab 1C01 (C, false-colored in blue) and donor #04 day 28 Fabs 1F03 (D, false-colored in red) and 1H09 (E, false-colored in red). (F–H) Low-resolution three-dimensional reconstructions of H5 HA in complex with donor #04 day 7 Fab 1C01 (F) and donor #04 day 28 Fabs 1F03 (G) and 1H09 (H). The ribbon diagram for the A/Indonesia/05/2005 H5 HA structure (in gold, Protein Data Bank [PDB] 4K62) is docked into the HA density. The ribbon diagram for the CR6261 structure (in blue, PDB 3GBM), as an example of a stem-binding antibody, is docked into the 1C01 density. The ribbon diagram for the C05 structure (in red, PDB 4FNL), as an example of an receptor binding site (RBS)-binding antibody, is docked into the 1F03 and 1H09 density.

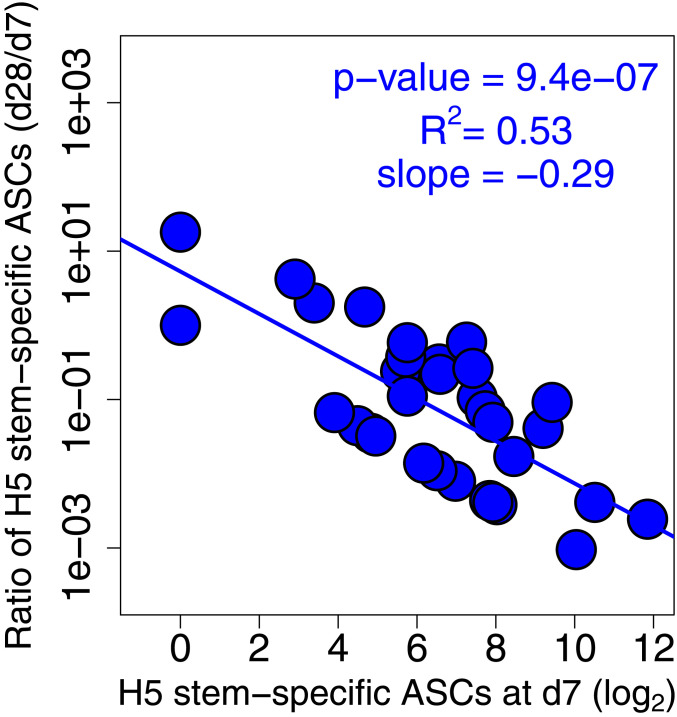

Diminished Response to the H5 Stem Region after the Booster Immunization Is due to Epitope Blocking.

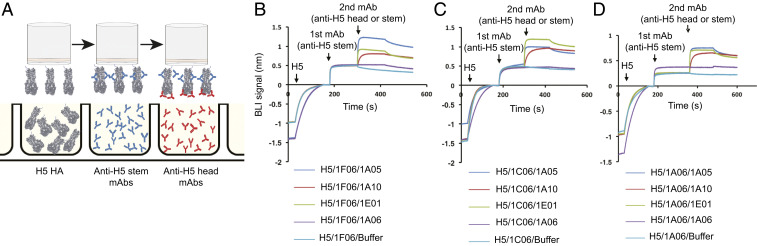

Why did the second immunization elicit a plasmablast response that is largely directed against the H5 head and not the stem region? Mathematical modeling suggests that epitope masking could be a dominant factor explaining the decreased serum antibody responses in humans observed after repeat immunizations (28–30). In agreement with this notion, we did observe that the difference in frequency of H5 stem-specific plasmablasts measured at days 7 and 28 after vaccination inversely correlated with the magnitude of stem-specific plasmablast response at day 7 (Fig. 4). To test this point experimentally, we examined the capacity of stem-specific mAbs to block the binding of stem- and head-specific mAbs in a biolayer interferometry (BLI)-based assay (Fig. 5A). Saturating the H5 HA molecule with stem-binding mAbs did not interfere with the binding of H5 head-binding mAbs, but it completely blocked binding of additional HA stem-specific antibodies (Fig. 5 B–D). The mAbs used in Fig. 5 were derived from day 7 plasmablasts (stem) or day 28 plasmablasts (head) isolated from the same subject, #043. These data suggest that the robust plasmablast-derived antibody response directed against the H5 stem region induced early after first immunization blunted further boosting of the stem-specific response upon the second immunization.

Fig. 4.

Robust H5 stem-specific antibody secreting cells (ASCs) at day 7 preclude further boosting after second immunization. Negative correlation between the ratio of H5 stem-specific ASCs (d28/d7) and H5 stem-specific ASC frequency at day 7. Note that we plot log2(ASCs) on the x axis as titers are measured on a log2 scale, and we plot fold boost of ASC values using a logarithmic scale on the y axis.

Fig. 5.

Anti-H5 HA stem antibodies block further responses to H5 HA stem but not against the HA head. (A) A cartoon model depicting the BLI-based competition experiments between anti-H5 HA stem and head mAbs. (B–D) Data from the BLI-based competition experiments showing the binding of three different anti-H5 head mAbs (10.43.28.1A05, 10.43.28.1A10, and 10.43.28.1E01) after blocking with (B) 10.43.7.1F06, (C) 10.43.7.1C06, or (D) 10.43.7.1A06.

AS03 Adjuvant Enhances Antibody Responses from Both Naive and Memory B Cells.

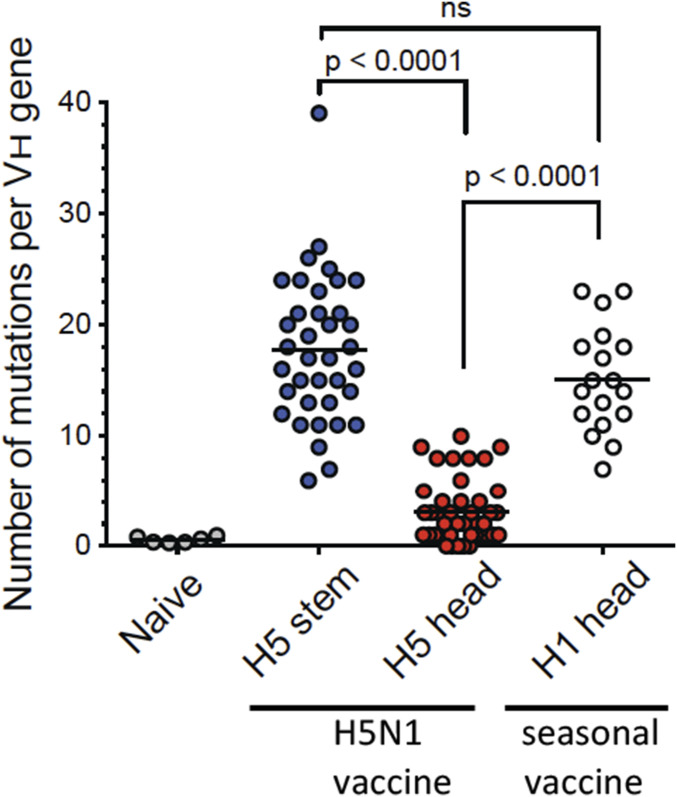

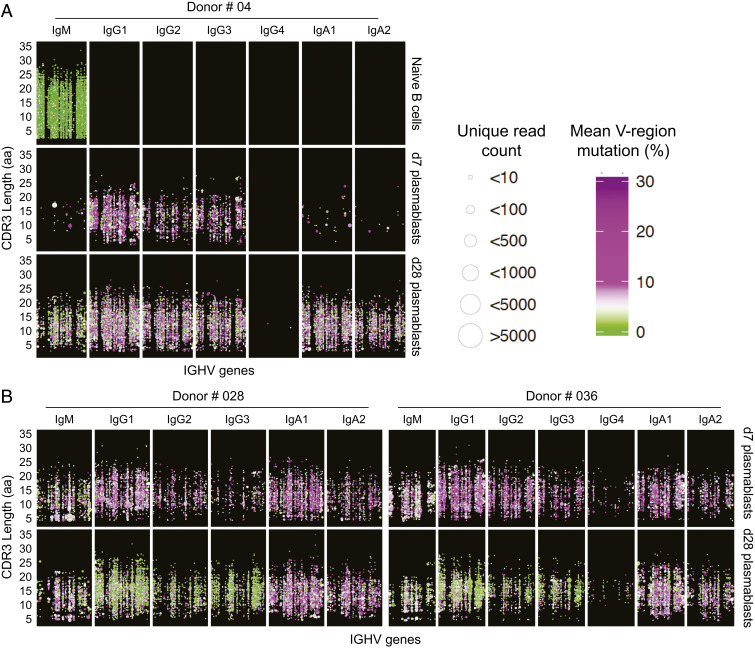

We next analyzed the degree of somatic hypermutation in the single-cell–sorted plasmablasts responsive against H5 HA stem and head epitopes (shown in Fig. 3). H5 HA stem-specific plasmablasts had an average of 17.75 mutations per IGH gene, which was not significantly different from monoclonal antibodies typically isolated after seasonal influenza virus vaccination consistent with the notion that these antibodies were derived from preexisting memory B cells (Fig. 6). In striking contrast, all of the H5 HA head-specific antibodies had a significantly lower level of somatic hypermutations (average = 3.11) consistent with these antibodies coming from naive B cells that were recruited to the response following immunization (Fig. 6). We also examined the global differences in somatic hypermutation (SHM) frequencies between bulk-sorted plasmablast populations isolated either after the first immunization (day 7) or after the second immunization (day 28) by sequencing the Ig heavy chain (IGH) genes from these two populations and also from naive B cells. As expected, IgM+ reads that possess no or very few mutations are the dominant sequences detected within sorted naive B cells (Fig. 7 A, Top). In contrast, virtually all antibody isotypes were represented in the reads extracted from the day 7 plasmablast populations (Fig. 7 A and B). Consistent with the SHM data obtained from the mAbs, day 7 plasmablasts possessed high levels of SHM (mean SHM for three donors: IgG1 7.81%, IgG2 7.71%, IgG3 7.56%). On the other hand, reads derived from plasmablasts isolated at day 28 showed lower levels of SHM especially those encoding IgG1 (4.52%), IgG2 (4.76%), and IgG3 (4.32%) subclasses (Fig. 7 A and B). These data suggest that the day 7 plasmablasts are predominantly derived from MBCs while those isolated at day 28 are largely derived from naive B cells. Taken together, these results show that the AS03 adjuvant is highly effective in enhancing antibody responses from both influenza-specific naive and memory B cells.

Fig. 6.

High levels of somatic hypermutations among anti-H5 HA stem monoclonal antibodies. Average number of SHMs detected in the IGHV of the H5 HA stem- (blue) and head-specific (red) plasmablast-derived mAbs. SHM frequency in naive B cells (gray) and H1 HA head-specific plasmablasts (white) isolated 7 d after seasonal (2015/16) influenza vaccination are shown for comparison. Each dot represents the SHM frequency of a single cell. P values are the results of unpaired t tests.

Fig. 7.

Predominance of highly mutated plasmablasts after first H5N1 immunization. (A) Overview of naive B cell and plasmablast IGHV gene repertoire following first and second H5N1 vaccination of donor #04. Each B cell clone identified across the longitudinal sampling is plotted based on the clone’s IGHV usage (x axis) and CDR3 length (y axis) with the size of the point reflecting the number of clone members observed and the color indicating the mean SHM of the clone members ranging from green for unmutated clones that lack evidence of affinity maturation, to white for ∼5% SHM and increasingly more purple for higher % SHM. Each panel row shows data for clones detected at a given time point for the indicated cell subset, with the B cell clones for each sample subset based on the isotypes that the clone members were associated with (panel columns). Points representing clones that share the same IGHV and CDR3 length were slightly offset to prevent overplotting. (B) Data from donors #028 and #036. Shown are SHM levels among plasmablasts isolated at day 7 vs. plasmablast isolated at day 28 after H5N1 vaccination.

Functional Characterization of the Anti-H5 Stem and Head Monoclonal Antibodies.

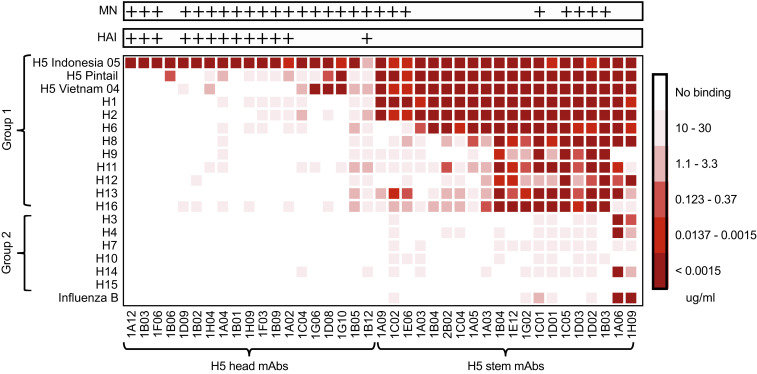

To determine the breadth of the stem-specific antibodies we examined their binding to representative recombinant HA molecules that belong to group 1 and group 2 influenza A viruses as well as a representative influenza B virus HA. We found that these mAbs were strikingly cross-reactive with some of them binding to HA molecules from both group 1 and group 2 and from influenza B viruses (Fig. 8). Several of these cross-reactive stem-binding mAbs also neutralized H5N1 virus in vitro as tested by microneutralization (MN) (Fig. 8, Top). These results show that the adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine recruited the most highly cross-reactive memory B cells from the preexisting pool of influenza-specific memory B cells. A striking contrast is provided by the extreme narrow specificity of the H5 HA head-specific antibodies (Fig. 8), which were mostly HAI+ (Fig. 8, Top). These mAbs were exquisitely specific for the immunizing H5N1 strain consistent with the recruitment of de novo naive B cells.

Fig. 8.

Anti-H5 HA stem monoclonal antibodies are broadly cross-reactive. Heat map showing the breadth of specificity for influenza family HAs of head- vs. stem-specific anti-H5 mAbs. The color scale indicates minimum binding concentration from white (no binding detected, ND) to dark red (minimum binding concentration of <0.0015 μg/mL). Antibodies were grouped depending on their binding patterns that indicate binding to the head domain (Left) or the stem (Right). All antibodies were also tested for their ability to neutralize in an MN assay and for HAI. Antibodies with detectable activity in these assays were marked “+.”

Discussion

In this study, we document the striking effect of the adjuvant, AS03, in enhancing influenza-specific antibody responses after vaccination of humans with the H5N1 inactivated vaccine. We show that the antibody response was biphasic; dominated by highly mutated, broadly cross-reactive plasmablasts after the first immunization and by minimally mutated, and strain-specific plasmablasts after the second immunization. Clonal and functional analyses of monoclonal antibodies derived from these plasmablasts revealed that the broadly cross-reactive antibodies originated from preexisting memory B cells and the H5 strain-specific antibodies were derived from naive B cells. Most of the broadly cross-reactive antibodies were directed to the conserved stem region of the influenza HA, whereas the strain-specific antibodies were directed to the H5 HA head region. Thus, the AS03 adjuvant enhanced antibody responses to both the head and stem regions of the HA molecule.

Our study participants are healthy young adults, and it is fair to assume that all of them had some level of preexisting immunity to seasonal influenza virus strains. The reason we observed such a strikingly biased HA stem-specific antibody response after the first immunization with the H5N1 vaccine is because of the high numbers of cross-reactive stem-specific memory B cells to this region and the extremely low number of memory B cells that are cross-reactive with the dramatically different HA head region of the avian H5 HA protein. We predict that in children who are naive to all influenza strains we would see a very different pattern in the dynamics of the HA head- versus stem-specific antibody responses after vaccination with the H5N1 vaccine. In this case the HA head response should dominate, and both head- and stem-specific responses will be derived from naive B cells. We also predict that the AS03 adjuvant will be effective in children, since our study shows that it is highly effective in enhancing antibody responses coming not only from memory B cells but also from naive B cells. In the elderly, we would predict that the antibody responses to both HA head and stem are likely to come from memory B cells. Their repeated exposure to many different influenza strains might lead to the generation of some cross-reactive memory B cells to the head region of H5 HA. Again, in this case we predict that the AS03 adjuvant will be effective because it very nicely enhances antibody responses derived from memory B cells. However, issues of immune senescence may also come into play, and there could be defective innate responses in the elderly that could dampen the effect of the adjuvant. Therefore, it will be of great interest to do a detailed study comparing the nonadjuvanted and adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine-induced B cell responses in the elderly.

An interesting observation from our studies was the reduced antibody responses to the stem region upon the second immunization. This showed a striking inverse correlation to the magnitude of the stem-specific plasmablast response after the first immunization. One explanation could be that the HA stem epitopes were masked at the time of boosting by the preexisting high titers of stem-specific antibodies induced by the first immunization (29, 30). We tested this experimentally in vitro, and the results of these blocking experiments were consistent with epitope masking playing a role in this inhibition. Thus, these results suggest that high levels of preexisting antibody could inhibit the recruitment and activation of memory B cells specific for the same antigen. This highlights one of the challenges of immunizing already immune individuals, which is often the case with influenza vaccination.

In summary, the comprehensive immunological analysis that we have performed in this study comparing an adjuvanted versus nonadjuvanted influenza vaccine in humans should provide important guidelines for the development for a universal influenza vaccine and also for the development of vaccines for other pathogens.

Methods

All studies were approved by the Emory University institutional review board. Healthy adult volunteers signed an informed consent and were given the monovalent, inactivated influenza vaccine A/Indonesia/05/2005 (H5N1) with or without the AS03 adjuvant (GlaxoSmithKline). Direct ELISpot to enumerate total and HA-specific plasmablasts, recombinant HA-specific ELISA, as well as HAI were performed as previously described (19). Generation and characterization of the recombinant human mAbs were performed as previously described (7). Sequencing and analysis of the Ig repertoire were performed as previously described (26). More detailed materials and methods are presented in the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Fatima Amanat and Daniel Kaplan for excellent technical assistance with protein expression. We also thank Elise Oster, Madison Mack, Jackson S. Turner, and Bassem M. Mohammed for editorial assistance. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grants U19 AI109946 (to F.K.), and HHSN2722019 (to R. Ahmed), Grants R21 AI139813 and U01 AI141990 (to A.H.E.), and grants from the NIAID-funded Centers of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS; HHSN272201400004C [to R. Ahmed] and HHSN272201400008C [to F.K. and A.H.E.]). R. Antia and V.I.Z. are also supported by U19 AI117891. The vaccination study was supported by The Human Immunology Project Consortium (HIPC) U19AI090023 (B.P.). S.D.B. is supported by NIAID Grants R01AI130398, R01AI127877, and U19AI057229.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: Structures have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (accession codes: 1F03: EMD-20570 1H09: EMD-20571 1C01: EMD-20569) and BioProject Sequence Read Archive (accession no. PRJNA533650).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1906613117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability Statement.

B cell receptor (BCR) deep-sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA533650. Electron microscopy maps have been deposited to the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession nos. 1F03: EMD-20570, 1H09: EMD-20571, and 1C01: EMD-20569.

References

- 1.Francis T., Jr., Vaccination against influenza. Bull. World Health Organ. 8, 725–741 (1953). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellebedy A. H., Webby R. J., Influenza vaccines. Vaccine 27 (suppl. 4), D65–D68 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krammer F., Palese P., Advances in the development of influenza virus vaccines. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 167–182 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirst G. K., Studies of antigenic differences among strains of influenza A by means of red cell agglutination. J. Exp. Med. 78, 407–423 (1943). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webby R. J., Webster R. G., Are we ready for pandemic influenza? Science 302, 1519–1522 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellebedy A. H., Ahmed R., Re-engaging cross-reactive memory B cells: The influenza puzzle. Front. Immunol. 3, 53 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulligan M. J. et al.; DMID 13-0032 H7N9 Vaccine Study Group , Serological responses to an avian influenza A/H7N9 vaccine mixed at the point-of-use with MF59 adjuvant: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 312, 1409–1419 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treanor J. J., Campbell J. D., Zangwill K. M., Rowe T., Wolff M., Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated subvirion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1343–1351 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrammert J. et al., Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature 453, 667–671 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valkenburg S. A. et al., Immunity to seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses. Microbes Infect. 13, 489–501 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu C., Ellebedy A. H., Wrammert J., Ahmed R., B cell responses to influenza infection and vaccination. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 386, 381–398 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schild G. C., The influenza virus: Antigenic composition and immune response. Postgrad. Med. J. 55, 87–97 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nachbagauer R. et al., Broadly reactive human monoclonal antibodies elicited following pandemic H1N1 influenza virus exposure protect mice against highly pathogenic H5N1 challenge. J. Virol. 92, e00949-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paules C. I., Marston H. D., Eisinger R. W., Baltimore D., Fauci A. S., The pathway to a universal influenza vaccine. Immunity 47, 599–603 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paules C. I., Sullivan S. G., Subbarao K., Fauci A. S., Chasing seasonal influenza—The need for a universal influenza vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 7–9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erbelding E. J. et al., A universal influenza vaccine: The strategic plan for the national institute of allergy and infectious diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 347–354 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X. et al., Stockpiled pre-pandemic H5N1 influenza virus vaccines with AS03 adjuvant provide cross-protection from H5N2 clade 2.3.4.4 virus challenge in ferrets. Virology 508, 164–169 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chada K. E., Forshee R., Golding H., Anderson S., Yang H., A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-reactivity of antibodies induced by oil-in-water emulsion adjuvanted influenza H5N1 virus monovalent vaccines. Vaccine 35, 3162–3170 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Giudice G., Rappuoli R., Inactivated and adjuvanted influenza vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 386, 151–180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salk J. E., Laurent A. M., Bailey M. L., Direction of research on vaccination against influenza; new studies with immunologic adjuvants. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 41, 669–677 (1951). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard L. M. et al., AS03-Adjuvanted H5N1 avian influenza vaccine modulates early innate immune signatures in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Infect. Dis. 219, 1786–1798 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khurana S. et al.; and the CHI Consortium , AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine promotes antibody diversity and affinity maturation, NAI titers, cross-clade H5N1 neutralization, but not H1N1 cross-subtype neutralization. NPJ Vaccines 3, 40 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galson J. D., Trück J., Kelly D. F., van der Most R., Investigating the effect of AS03 adjuvant on the plasma cell repertoire following pH1N1 influenza vaccination. Sci. Rep. 6, 37229 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong S.-S. et al., H5N1 influenza vaccine induces a less robust neutralizing antibody response than seasonal trivalent and H7N9 influenza vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2, 16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galassie A. C. et al., Proteomics show antigen presentation processes in human immune cells after AS03-H5N1 vaccination. Proteomics 17, 1600453 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G.-M. et al., Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9047–9052 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith K. et al., Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nat. Protoc. 4, 372–384 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellebedy A. H. et al., Induction of broadly cross-reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stem region following H5N1 vaccination in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 13133–13138 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarnitsyna V. I. et al., Masking of antigenic epitopes by antibodies shapes the humoral immune response to influenza. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140248 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarnitsyna V. I., Lavine J., Ellebedy A., Ahmed R., Antia R., Multi-epitope models explain how pre-existing antibodies affect the generation of broadly protective responses to influenza. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005692 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

B cell receptor (BCR) deep-sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA533650. Electron microscopy maps have been deposited to the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession nos. 1F03: EMD-20570, 1H09: EMD-20571, and 1C01: EMD-20569.