Abstract

Migrant workers play a significant role in the economy of Bangladesh, pumping approximately USD15 billion into the economy that directly contributes to the socio-economic development of Bangladesh every year. These workers and their dependents are in a socially vulnerable and economically difficult situation due to the dire impacts of the COVID-19. Migrant workers from Bangladesh in other countries are facing adverse impacts such as unemployment, short working hours, isolation, poor quality of living, social discrimination and mental pressure while their dependents at home are facing financial crisis due to the limited or reduced cash flow from their working relatives. A significant number of migrant workers have been sent back to Bangladesh and many are in constant fear of being sent back due to the impacts of COVID-19 in their host countries. Thus, COVID-19 intensifies numerous socio-economic crises such as joblessness, consumption of reserve funds by family members, and shrinking of the country’s remittance inflow. In this situation, the most urgent and important need is to give financial security and social safety to the workers abroad and those who have returned to Bangladesh. Apart from diplomatic endeavors to maintain the status quo of policy, the government of Bangladesh may take initiatives to provide financial support to these workers as a short-term strategy to overcome hardships during the pandemic and design a comprehensive plan with a detailed database of all migrant workers to create a need-based and skilled workforce as a long-term solution. These strategies can mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 at present and address migration related problems in future.

Keywords: COVID-19; Migrant workers; Remittance; National economy; Unemployment, Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Migrants from Bangladesh including migrant workers as well as students and researchers are working in Europe, the USA, Canada, Australia, the Middle East, Singapore, Malaysia and many other regions. Currently, there are around 13 million Bangladeshis working abroad (Karim & Islam, 2020, MoEWOE (Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment)., 2019). These workers make a significant contribution to the development of Bangladesh, as they send approximately USD15 billion as remittance into the country’s economy every year (BMET (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training)., 2020, Mannan and Farhana, 2014, Masuduzzaman, 2014). This inbound remittance has contributed to the rise in the record forex reserve of the country to USD36.14 billion end of the financial year 2019–2020 (BB, 2020a). It plays a huge role in strengthening the foreign reserve of Bangladesh as well as keeps the nation’s economy dynamic and supports mega infrastructure projects, such as the Padma Bridge (Liton & Hasan, 2012).

Migrant workers from Bangladesh and their dependents are facing various economic and social hardships under the COVID-19 situation. Understanding these hardships is vital for Bangladesh to develop effective strategies to lessen the impacts. Therefore, by capturing the economic and social impacts of COVID-19 on migrant workers, a few policy interventions are recommended as strategies to overcome the problems.

2. Economic impact

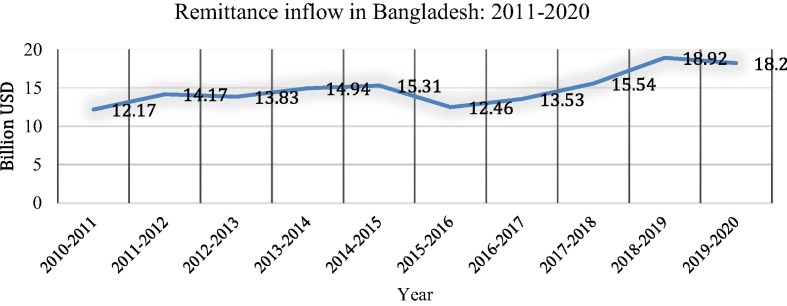

Remittance sent home by migrant workers is one of the main pillars of the economy of Bangladesh, contributing 12% in GDP and generating 9% employment of the total active workforce of Bangladesh (Ali, 2014, BMET (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training)., 2020, Karim, 2020, Mannan and Farhana, 2014). Remittance is continuously flowing into the country’s economy every year as can be seen in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Remittance inflow in the last 10 years (2011–2020) in Bangladesh. Source: BMET, 2020.

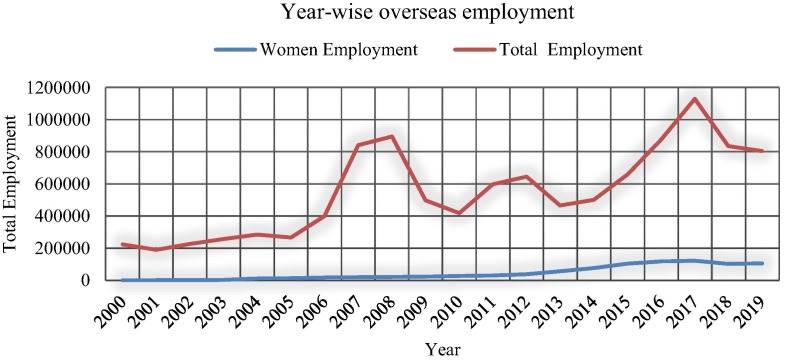

Overseas employment contributes significantly to easing Bangladesh’s employment market as the outflow of migrant workers increases 22% annually (ADB, 2016). According to the MoEWOE (Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment)., 2019, BMET (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training)., 2020), each year around 700,000 Bangladeshi migrant workers go abroad for jobs. The year-wise (2000–2019) trend of migrant workers going abroad can be seen in Fig. 2 . A large number of female workers are also part of this group, and their number is increasing year by year as can be seen in Fig. 2. COVID-19 has dealt a heavy blow to all migrant workers’ job prospects as well as to Bangladesh’s overseas job market and consequently reduced the amount of remittance inflow (Palma, 2020).

Fig. 2.

Year-wise overseas employment (2000–2019) of Bangladeshi workers. Source: BMET, 2020.

Those who are working in the unstructured and non-mainstream employment sectors, such as taxi drivers, restaurant workers, day laborers, small vendors, construction workers, industrial laborers and so forth, are facing a serious crisis to maintain their earnings (Abdullah and Hossain, 2014, Ali, 2014) and their jobs will remain uncertain for an indefinite period. Many have been rendered jobless (Sumon, 2020), have lost their jobs or received low wages or no pay (BB (Bangladesh Bank)., 2020a, BMET (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training)., 2020). The economic impacts of COVID-19 on migrant workers will hugely influence the remittance flow and the economy (Sutradhar, 2020), with serious impacts on the GDP growth rate of Bangladesh.

In addition, migrant workers who came home on leave and who were waiting to fly back to their workplaces after getting work visas have not been allowed to enter host countries that imposed shutdowns or travel bans (RMMRU, 2020). The bulk of the remittances originates from Bangladeshis who work in the Middle East and Southeast Asian countries. To curb COVID-19 transmission, most countries where migrant workers are working have enforced lockdowns, which has shrunk working hours and job opportunities and resulted in low earnings and periodic unemployment (Sumon, 2020). Many host countries have allocated a big portion of their national budget for the recovery of their own people, which is going to further hamper development and reduce job and hiring opportunities for migrant workers. If the lockdown and economic impacts of COVID-19 continue, there will be profound impacts on the overseas job market for the migrant workers of Bangladesh. It is reported that a total of 666,000 migrant workers were sent back to Bangladesh after the coronavirus outbreak, and two million face possible deportation during and after the pandemic (TBS, 2020c).

In this situation, migrant workers need short-term financial protection. To stop the return of migrant workers immediately to Bangladesh, the government of Bangladesh has emphasized diplomatic channels for ensuring workers’ jobs until the situation returns to normalcy and requested workers not to return unless they are forced to do so (MoFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)., 2020a, MoFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)., 2020b) because returning migrant workers will pose a threat of unemployment that will intensify Bangladesh’s current decline in employment that is occurring due to COVID-19.

3. Social impact

Remittance greatly contributes to the socio-economic development of migrant workers. It brings financial solvency and enhances workers’ living standard. Researchers have found that remittance sent by workers is typically used to repay loans for migration, buy land and construct houses, invest in business, increase income and savings, take part in community development, improve health and nutrition, attend social ceremonies and so on (Islam, 2011). However, the coronavirus outbreak has threatened 13 million migrant workers and their livelihoods. Thus, Bangladesh has become one of the most severely affected countries by the COVID-19 pandemic. Travelers as well as returning migrant workers and their relatives coming from China, Italy and the Middle East are believed to be the original bearers of the coronavirus to Bangladesh, and it has since spread throughout the country. With the increase of incidents of COVID-19 around the world as well as in Bangladesh, commercial flights have been limited in and outside the country. As a result, an immense number of migrant workers are trapped, affected and in dire circumstances (Palma, 2020). The situation may delay their return to the host countries with new restrictions of banning and suspension of international flights. The recent restriction of entry to European countries including Italy has led to not only financial loss but also social discrimination at home and abroad (DS, 2020, TBS (The Business Standard)., 2020b). Restrictions categorically imposed on Bangladeshis have tarnished the image of the country and 13 million expatriates across the globe. These restrictions also intensify the psychological stress of migrant workers and their family members due to their uncertain future.

Among those who have been allowed to remain in their host countries, many migrant workers are quarantined in shabby living places, mentally disturbed because of concern about their jobs and families at home, and worried about being sent back to Bangladesh (Sumon, 2020). They are also fearful of being affected by the virus since they often reside in densely populated dormitories and houses, which are deemed epicenters for the COVID-19 outbreak (Sumon, 2020). A sub-section of migrant workers comprising the skilled work force, especially doctors and nurses, have become the most vulnerable group among migrant workers in host countries during the pandemic.

The rapid transmission of COVID-19 and its health threats all around the world have led to a unique situation in which the social acceptance of returning Bangladeshis migrant workers and their relatives from abroad has fallen drastically. A recent survey discovered that 29% of returning migrant workers were not welcomed back by relatives and neighbors (TBS, 2020a), especially those coming home from Italy, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Many have faced many harsh situations as their family members and neighbors at home did not want them to come back to their communities because of the fear of spreading infection (Karim & Islam, 2020, RMMRU, 2020).

While many migrant workers are not being welcomed to Bangladesh, those remaining overseas are also facing a very bad situation in terms of fulfilling essential needs. More than 843 overseas Bangladeshis have died of COVID-19 in 19 countries, among whom were a good number of doctors based in the US, UK, Italy and Saudi Arabia (Noman & Siddiqui, 2020; Siddiqui, 2020). After spending 5–20 years abroad, many migrant workers have already lost their youth and sacrificed a happy family life (Ullah, 2013). Their sudden return to Bangladesh intensifies their critical situation as 87% returnee expatriates lack an income source even though they are required to pay loans and spend for livelihood (TBS, 200d). This means that poor workers who migrated to find better-paying jobs and escape poverty are returning to the poverty they tried to escape.

There is a chance of an economic recession all around the world due to the impacts of COVID-19 which may keep Bangladeshi migrant workers from getting jobs and maintaining employment abroad, regardless of whether they have work visas or work contracts. In addition, the remittance sent home by migrant workers plays a key role in ensuring the livelihood of about 30 million of their dependents. The loss of this remittance means that migrant workers and their dependents will confront various social and health issues such as unemployment, exhaustion of investment funds, food and nutrition insecurity, inability to pay for their dependents’ education, lack of health facilities, depression, child labor, broken families, social disparity and even an increase in suicide (Asis, 1995, Chowdhury, 2011, Jan et al., 2017).

4. Recommendations

The governments of the migrant workers’ host countries have undertaken various initiatives to reduce the effects of COVID-19 on migrant workers. In spite of those initiatives, migrant workers are still at risk and vulnerable due to the cascading effects of COVID-19 in the socio-economic systems of the host countries. To minimize the risk and vulnerability of the migrant workers the following strategies can be taken:

-

▪

Status quo policy for the migrant workers could be followed until the world returns to normalcy. The government should continue the practice of giving 2% percent money incentives on inflow remittances of USD1500 and they should waive the documentation required when people send USD5000 (BB, 2020b). The MoEWOE announced USD5900-8260 loans for these workers to pursue income-generating activities, particularly agriculture. The government has also taken the step of paying about USD60 as a one-time payment to every returning migrant worker. Furthermore, the government has created a fund of about USD 2.4 million to sanction loans to them under the midterm support scheme which can be considered a noteworthy policy option to face the impacts of COVID-19 on migrant workers (Bhuyan, 2020, MoEWOE (Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment)., 2019).

-

▪

A detailed database needs to be prepared to trace and track all migrant workers; all exit and entry records may be mandatorily included; illegal migration should also be stopped following various administrative and legal measures. Trained and professional personnel in Bangladesh’s foreign mission should be appointed so that they can handle migrant workers’ problems with care.

-

▪

Migrant workers from South Asian nations working abroad are probably the greatest victims of the economic effects of the pandemic (Budhathoki, 2020). Therefore, a holistic and aggregated South Asian platform can likewise be used to address these impacts on migrant workers. In particular, the existing Colombo Process (a foundation of Asian worker-sending nations) and Abu Dhabi Dialog (a foundation of worker-receiving countries) should take the initiative to propose holistic measures in response to the adverse impacts on migrant workers from all South Asian nations. Above all, Bangladesh must utilize its diplomatic efforts and other networks to secure migrant workers’ jobs as well as their health and social life in host counties.

5. Conclusion

Bangladesh has no other option than to continue the inflow and surge of overseas employees to maintain its remittance flow if it wants a flourishing economy. Immediate actions are required to support migrant workers home and abroad socially and financially. For returning migrant workers and their dependents, the agricultural sector can be an option to invest and generate employment as well as livelihood. The government may use the skills of the returning migrant workers in various sectors of Bangladesh as well with a particular focus on skills training in nursing, health technology, management, medicine, and hospitality as part of its migration strategy to make these workers more in demand overseas. Illegal workers who are in the most vulnerable situations should also be taken under supervision and surveillance.

The government of Bangladesh must make long-term plans for the security of those who go to work in other countries and set out a comprehensive plan to protect them so that Bangladesh can sustain its foreign reserve and address the economic shock in future. Moreover, multilateral collaboration can be developed to support the UN’s SGD of promoting safe, orderly and regular migration.

References

- Abdullah A., Hossain M. Brain drain: Economic and social sufferings for Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Humanity, Art and Literature. 2014;1(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). (2016). Overseas Employment of Bangladeshi Workers: Trends, Prospects, and Challenges, ADB Briefs, August 16. Available at: https://www.adb.org/publications/overseas-employment-bangladeshi-workers, [10 May 2020].

- Ali M.A. Socio-economic impact of foreign remittance in Bangladesh. Global Journal of Management and Business Research. 2014 [12 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Asis M.M. Overseas employment and social transformation in source communities: Findings from the philippines. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 1995;4(2–3):327–346. [Google Scholar]

- BB (Bangladesh Bank). (2020a). Monthly data of Wage Earner’s Remittance. Available at: https://www.bb.org.bd/econdata/wageremitance.php, [18 May 2020].

- BB (Bangladesh Bank). Cash incentives against remittance sent in legitimate way Available at 2020 [15 May 2020]

- Bhuyan, M.O.U. (2020), Steps needed to develop skills for overseas job seekers, The New Age Bangladesh, 2 June. Available at: www.newagebd.net, [2 June 2020].

- BMET (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training). (2020). Overseas Employment and Remittance from 1976-2020 (February). Available at: http://www.old.bmet.gov.bd/BMET/stattisticalDataAction, [9 May 2020].

- Budhathoki, A. (2020). Middle East Autocrats Targets South Asian Worker, The Foreign Policy. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/23/middle-east-autocrats-south-asian-workers-nepal-qatar-coronavirus, [23 April 2020].

- Chowdhury M.B. Remittances flow and financial development in Bangladesh. Economic Modelling. 2011;28(6):2600–2608. [Google Scholar]

- DS (2020). Italy bars entry to passengers from Bangladesh till October 5. Available at: www.thedailystar.net, [9 July 2020].

- Islam N. Bangladesh Manpower Employment and Training; Dhaka: 2011. Bangladesh Expatriate Workers and their Contribution to National Development. [Google Scholar]

- Karim M.R. Overseas employment and sustainable development goals in Bangladesh: Connectedness, contribution and achievement confusion. Bangladesh Journal of Public Administration. 2020;28(Special Issue):70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jan C., Zhou X., Stafford R.S. Improving the health and well-being of children of migrant workers. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2017;95(12):850. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.196329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim M.R., Islam M.T. COVID-19 and the Vulnerability of Overseas Bangladeshi. The Khabarhub. 2020 4 May. Available at: www.english.khabarhub.com, [4 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Liton S., Hasan R. Padma bridge with own fund. The Daily Stary. 2012 Available at: www.thedailystar.net. [9 July 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Mannan D.K.A., Farhana K. Legal status, remittances and socio-economic impacts on rural household in Bangladesh: An empirical study of Bangladeshi migrants in Italy. Remittances and Socio-Economic Impacts on Rural Household in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study of Bangladeshi Migrants in Italy. 2014 Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2504921, [2 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Masuduzzaman M. Workers’ remittance inflow, financial development and economic growth: A study on Bangladesh. International Journal of Economics and Finance. 2014;6(8):247–267. [Google Scholar]

- MoEWOE (Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment). (2019). Annual Report 2018-2019. Available at: www.probasi.gov.bd., [5 May 2020].

- MoFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs). (2020a). Special Discussion with eleven Bangladeshi envoys appointed in Gulf countries through videoconferencing. https://mofa.gov.bd/site/press_release/149c9382-e337-4988-a89f-f80f728c00a8, [28 April 2020].

- MoFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs). (2020b). Migrants workers were requested not to return unless they are forced back. https://mofa.gov.bd/site/view/service_box_items/PRESS%20RELEASES/site/press_release/0ad56541-6d34-464a-b4f2-9f69a6526bc7, [30 April 2020].

- Noman M., Siddiqui K. List of Bangladeshi expats dying of Covid-19 growing. The Business Standard. 2020 7 June. Available at: www.tbsnes.net, [ 7 June 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Palma P. Coronavirus pandemic: A big blow to overseas jobs. The Daily Star. 2020 4 April. Available at: www.thedailystar.net, [4 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- RMMRU Protection of Migrants during COVID-19 Pandemic Situation Analysis of RMMRU and Tasks Ahead. Available at 2020 (Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit) [13 May 2020]

- Siddiqui K. Infections among Bangladeshi migrants on the rise. The Business Standard. 2020 6 May. Available at: www.tbsnews.net, [6 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Sumon S. Thousands of Bangladeshi could leave Kuwait next week. Arab News. 2020 6 May. Available at: www.arabnews.com, [6 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Sutradhar S.R. The impact of remittances on economic growth in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies. 2020;14(275–295):1. [Google Scholar]

- TBS (The Business Standard). (2020a). Expat workers: A pillar of economy itself needs support now, 22 May. Available at: www.tbsnews.net, [30 May 2020].

- TBS (The Business Standard). (2020b). Bangladesh not eligible for Schengen visa as EU reopens borders, 28 June. Available at: www.tbsnews.net, [28 June 2020].

- TBS (The Business Standard). (2020c). 20 lakh Bangladeshi migrants may face deportation. Available at: www.tbsnews.net, [10 July 2020].

- Ullah A.A. Mother’s Land and Others’ Land: “Stolen” Youth of Returned Female Migrants. Gender, Technology and Development. 2013;17(2):159–178. [Google Scholar]