Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common inflammatory skin diseases affecting children and adults. The intense pruritus and rash can be debilitating, significantly impairing quality of life. Until recently, treatment was largely nonspecific and, in severe disease, sometimes ineffective and/or fraught with many side effects. Now, multiple agents targeting specific disease pathways are available or in development. Two new therapies, crisaborole and dupilumab, have become available since 2016, and dupilumab has dramatically improved outcomes for adults with severe AD. This article provides an overview of AD, including strategies for differential diagnosis and assessment of disease severity to guide treatment selection. Key clinical trials for crisaborole and dupilumab are reviewed, and other targeted treatments now in development are summarized. Two cases, representing childhood-onset and adult-onset AD, are discussed to provide clinical context for diagnosis, severity assessment, and treatment selection and outcomes.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Eczema, Infant onset, Adult onset, Differential diagnosis, Severity assessment, Crisaborole, Dupilumab

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common inflammatory skin diseases, affecting 13% of children and approximately 7% of adults in the United States.1–5 Childhood-onset AD begins early in life, with 50% diagnosed in the first year of life and 85% by 5 years of age.4,6–8 However, AD can present at any age, with adult-onset reported by 26% of adult patients with AD.9 Although AD often resolves during childhood, it persists through adulthood in 20% to 50% of patients.10,11

Clinical presentation and severity of AD varies widely, and diagnosis is not always straightforward, especially in adults.12 The disease course is chronic but intermittent, and when active, the intense pruritus and rash can be debilitating. The burden of symptoms may be profound, as may the impact on quality of life (QOL), particularly with moderate-to-severe disease.10,13 Depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance are frequent comorbidities.14–17 Now, as more effective, targeted treatments emerge, correct diagnosis along with appropriate assessment of severity is essential to determining the best strategies for control. Two targeted treatments, crisaborole and dupilumab, have been approved since 2016, and many others are showing promise.

This article provides an overview of AD and steps in clinical diagnosis and severity assessment, along with a discussion of traditional and newer approaches to managing the disease that include targeted topical and systemic agents. Two case studies, a child and an adult, are presented to provide clinical context.

DISEASE COURSE

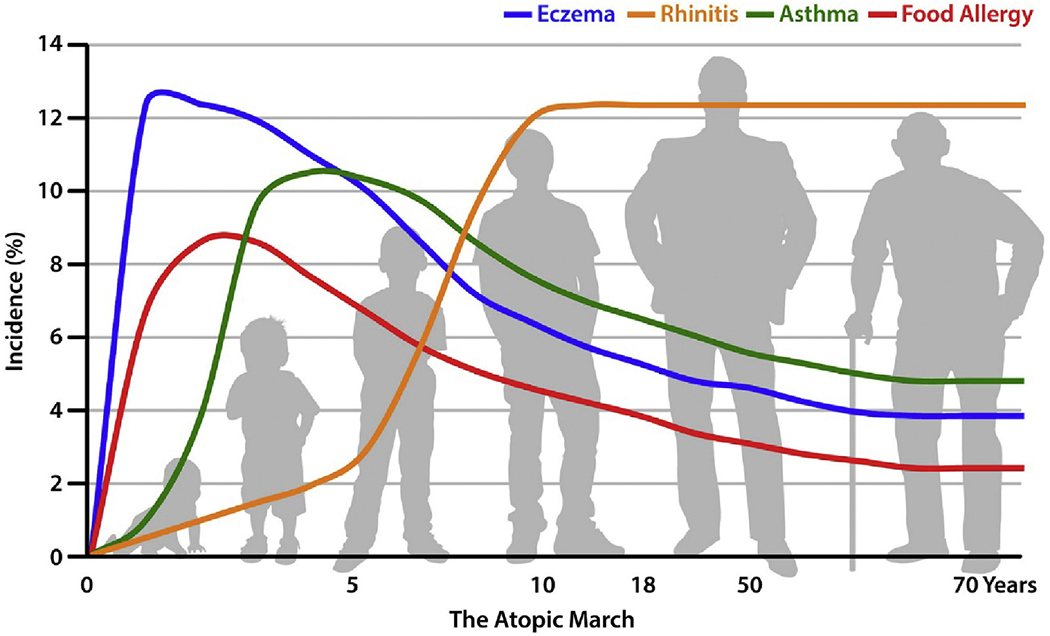

AD has a heterogeneous course that may include intermittent, waxing and waning, and chronic persistent disease. Severity of AD is variable, and it can be recalcitrant to treatment.1,2 The etiology is complex and incompletely understood. Skin barrier abnormalities and immune dysregulation, including excessive T helper 2 (TH2 and TH22) cell activity, are thought to contribute, as do genetic and environmental factors.18–20 A family history of atopic disease, including asthma and allergic rhinitis, predisposes to development of AD and suggests shared causal genetic and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Furthermore, in a subset of patients, onset of AD precedes that of other atopic diseases over the lifespan, typically progressing with food allergies, then asthma, and then allergic rhinitis in a pattern known as the “atopic march” (Figure 1).21 However, there are many variations in the trajectory. For example, some patients with AD never develop other atopic diseases, whereas others develop asthma or allergic rhinitis but not food allergies, and still others experience a rapid development of multiple atopic diseases over a short period.22

FIGURE 1.

The atopic march. The incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD) peaks early in infancy, preceding development of the atopic march. Evidence supports a causal link between AD and subsequent onset of other atopic diseases. Adapted from Czarnowicki et al.21 Copyright (2017), The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

DIAGNOSIS OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS

A diagnosis of AD is made on the basis of clinical presentation and history, with exclusion of multiple erythematous and eczematous conditions. Diagnosis is generally straightforward in infants and young children, but can be challenging in severe cases and in adults.

In infants, the skin lesions often first appear at 2 to 6 months of age (see case 1, “Eddie F”).3,8,23 Papules and papulovesicles may form large plaques that ooze and crust. They typically affect the face, hands, and extensors, but the scalp, neck, and trunk may also be involved. Notably, AD usually spares the diaper area; however, diaper dermatitis is very common in children with AD.24 Although some infants start with flexural disease (affecting the antecubital and popliteal fossae, wrists, and ankles), this generally appears after approximately 1 year of age.

Some conditions to rule out when diagnosing AD in children include seborrheic dermatitis, scabies, contact dermatitis, and psoriasis.25 Rare immunodeficiency-associated skin conditions, such as hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES), Netherton syndrome, and Omenn syndrome, may also resemble AD; they can often be distinguished by the presence of rash at or shortly after birth and other features. In newborns with HIES, the rash is often an eosinophilic folliculitis affecting the scalp and face26; in Netherton and Omenn syndromes, infants may have failure to thrive or chronic diarrhea in addition to the newborn rash.25 HIES is now also known to be caused by several genetic mutations; for example, patients with STAT3 mutations often have skin abscesses, and patients with DOCK8 mutations often have cutaneous viral infections.27,28 Genetic testing can help to differentiate these disorders from AD.25

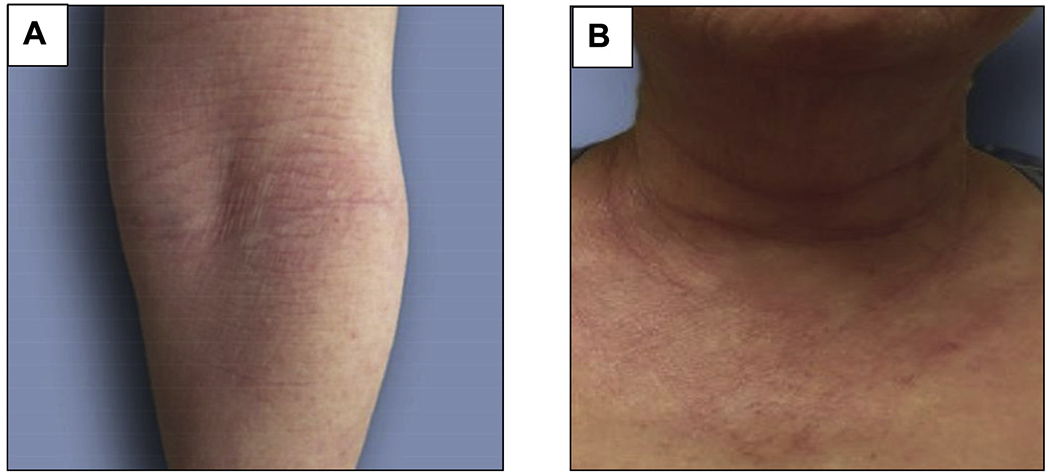

Compared with childhood-onset AD, presentation of adult-onset AD is more heterogeneous.12,29 There is more variation in lesion morphology and distribution and a greater predilection for the head, neck, hands, and feet (see case 2, “Diana K”).29 Important differential diagnoses include psoriasis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Paraneoplastic dermatitis may present with classical features of AD, but instead may portend lymphoma or other malignancies.30 Eczema-like cutaneous drug eruptions can also mimic AD; typical culprits include calcium channel blockers and possibly other antihypertensive agents.31 Thus, clinicians should always assess medication history in adults with suspected AD.12

In both children and adults, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) should be considered as an important alternative or concomitant diagnosis, as ACD may mimic AD or present together with AD, respectively.32,33

Over the years, several sets of criteria have been developed to assist with the diagnosis of AD. The Hanifin-Rajka (H-R) criteria (Table I) are comprehensive and generally considered the “gold standard” for AD diagnosis.3,34 The United Kingdom Working Party (UKWP) criteria (Table II) are essentially an abridged version of the H-R criteria and tend to work better for diagnosis in children than adults.35 The UKWP and H-R criteria have both been validated and tested in various populations.3 The American Academy of Dermatology has developed a streamlined version of the H-R criteria that has yet to be validated, but is suitable for clinical use.3

TABLE I.

Hanifin and Rajka criteria for diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD)34

| Major criteria (3 of 4 must be met) |

| (1) Pruritus |

| (2) Typical morphology and distribution |

| • Flexural lichenification in adults |

| • Facial and extensor involvement in infancy |

| (3) Chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis |

| (4) Personal or family history of atopic disease (asthma, allergic rhinitis, AD) |

| Minor criteria (3 of 23 must be met) |

| (1) Xerosis |

| (2) Ichthyosis/hyperlinear palms/keratosis pilaris |

| (3) Immediate skin test reactivity |

| (4) Elevated serum IgE |

| (5) Early age of onset |

| (6) Tendency for cutaneous infections |

| (7) Tendency to nonspecific hand/foot dermatitis |

| (8) Nipple eczema |

| (9) Cheilitis |

| (10) Recurrent conjunctivitis |

| (11) Dennie-Morgan infraorbital folds |

| (12) Keratoconus |

| (13) Anterior subscapsular cataracts |

| (14) Orbital darkening |

| (15) Facial pallor/facial erythema |

| (16) Pityriasis alba |

| (17) Anterior neck folds |

| (18) Pruritus when sweating |

| (19) Intolerance to wool and lipid solvents |

| (20) Perifollicular accentuation |

| (21) Food hypersensitivity |

| (22) Course influenced by environmental and/or emotional factors |

| (23) White dermatographism or delayed blanch to cholinergic agent |

TABLE II.

UK Working Party criteria for diagnosis of AD35

| Must have: an itchy skin condition in the last 12 mo |

| Plus 3 or more of: |

| (1) Onset age <2 y (not used for children <4 y) |

| (2) History of flexural involvement |

| (3) History of generally dry skin |

| (4) Personal history of other atopic disease, or in children aged <4 y, history of atopic disease in a first-degree relative |

| (5) Visible flexural dermatitis |

AD, Atopic dermatitis.

ASSESSING SEVERITY OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS

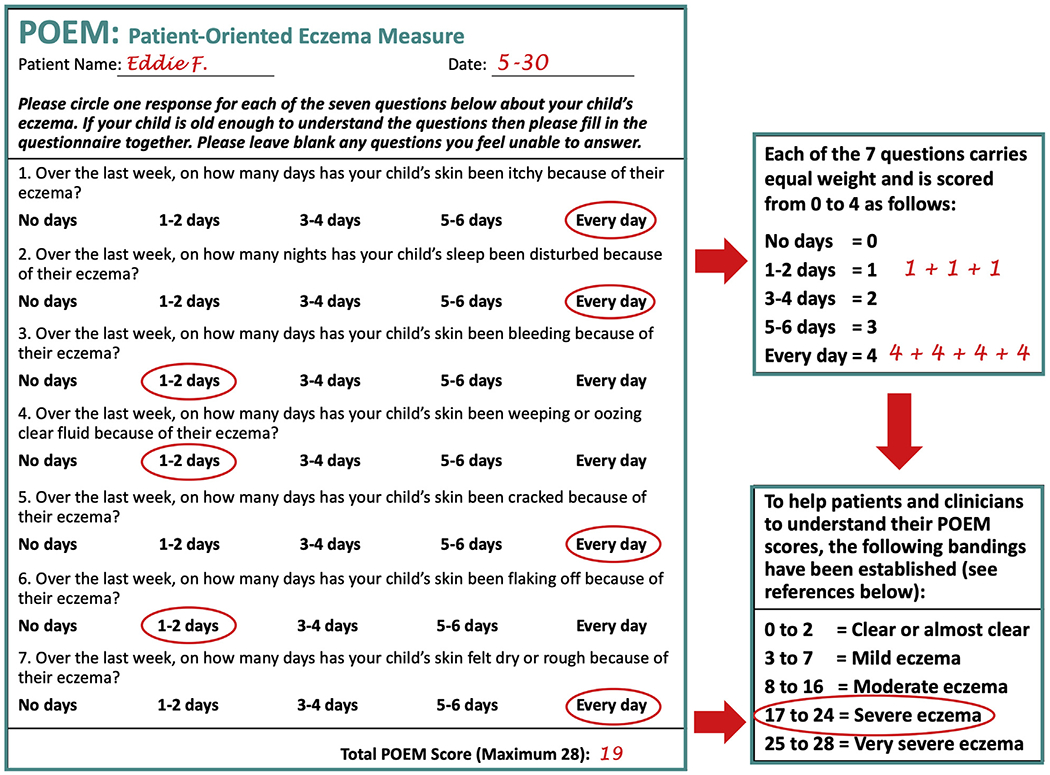

Assessment of disease severity is a guideline-recommended first step in treatment selection and valuable for monitoring treatment response.1 Numerous tools have been developed for severity assessment; these are summarized in Table III.36,37 Validated measures include the SCORing AD (SCORAD) index38 and the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI).39 Both take into account clinical signs and area of involvement; SCORAD also includes a subjective assessment of pruritus and sleep. SCORAD and EASI are used primarily in clinical trials and may be too time consuming for routine clinical practice. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)40 and Patient-Oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD) index41 are validated, patient-reported measures that are less time consuming and easier to use, but may be less accurate.43 Clinicians will need to consider advantages and shortcomings of the available tools when choosing which to use routinely in the clinic.

TABLE III.

| Scoring system | Parameters assessed | Severity rating | Validated |

|---|---|---|---|

| EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) | Area affected (percentage) for 4 regions, severity for regions | Clear (0) | ✔ |

| Almost clear (0.1-1.0) | |||

| Mild (1.1-7) | |||

| Moderate (7.1-21) | |||

| Severe (21.1-50) | |||

| Very severe (50.1-72) | |||

| SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) | Extent (sites affected + area percentage), intensity of lesions, patient-reported intensity of itch, and sleep loss | Clear (0-9.9) | ✔ |

| Mild (10.0-28.9) | |||

| Moderate (29.0-48.9) | |||

| Severe (49.0-103) | |||

| PO-SCORAD (Patient-Oriented SCORAD) | Extent (sites affected + area percentage), intensity of lesions, intensity of itch and sleep difficulties (assessed by patient or parent/caregiver) | Clear (0-9.9) | ✔ |

| Mild (10-28.9) | |||

| Moderate (29-48.9) | |||

| Severe (49-103) | |||

| POEM (Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure) | 7 symptoms scored over past week (itch, sleep, bleeding, weeping/oozing, cracking, flaking, and dryness/roughness) | Clear/almost clear (0-2) | ✔ |

| Mild (3-7) | |||

| Moderate (8-16) | |||

| Severe (17-24) | |||

| Very severe (25-28) | |||

| Mild (0-5) | ✔ | ||

| Moderate (6-10) | |||

| Severe (11-30) | |||

| Pruritus-NRS (Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale) | Patient-reported itch, scale of 1-10 (0 = no itch; 10 = worst itch imaginable) | Mild (0-3) | No |

| Moderate (4-6) | |||

| Severe (7-10) | |||

| TIS (Three-Item Severity Scale) | Subjective evaluation of 3 intensity items (erythema, edema/papulation, and excoriations) for a representative lesion (scale of 1-3 for each) | Mild (0-2) | No |

| Moderate (3-5) | |||

| Severe (6-9) | |||

| IGA (Investigator Global Assessment) | FDA categorization of AD severity based on the investigator's subjective assessment of a representative lesion | 0 = clear | No |

| 1 = almost clear | |||

| 2 = mild | |||

| 3 = moderate | |||

| 4 = severe |

AD, Atopic dermatitis; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; QOL, quality of life.

STEP-CARE MANAGEMENT OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS

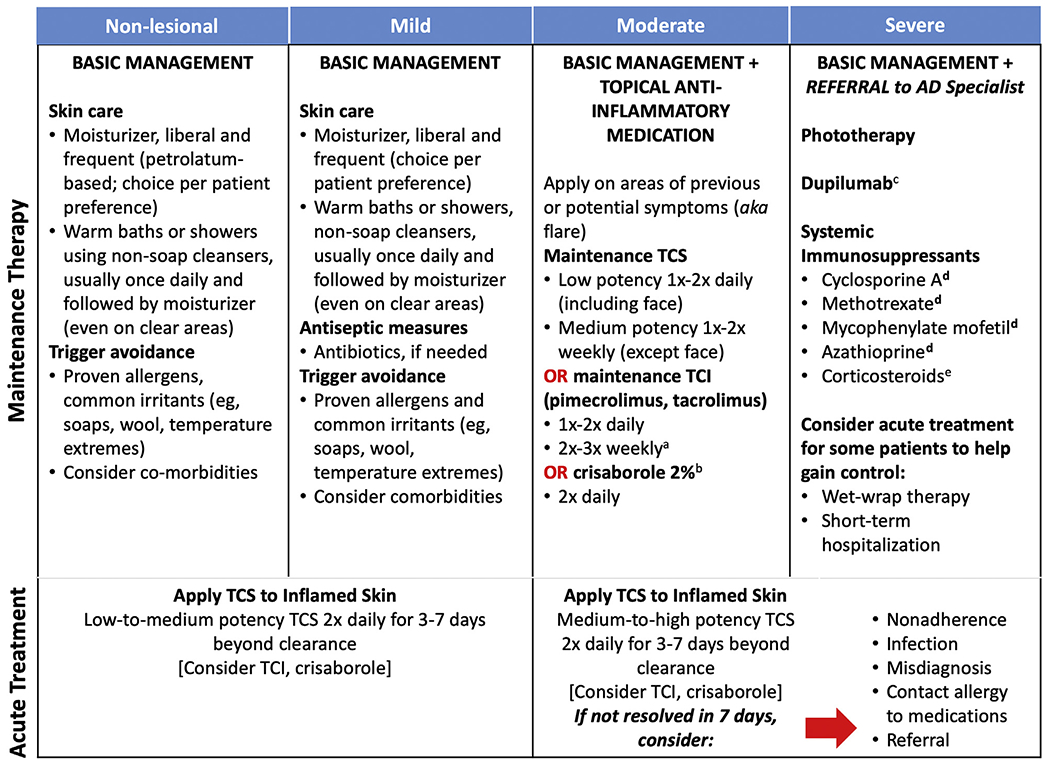

Treatment of AD follows a multifaceted, stepwise approach that is tailored according to disease severity (Figure 2).4,37 For all patients, basic management and flare prevention consists of daily showers or baths followed immediately by the application of emollients and moisturizers, with avoidance of triggers such as irritants, aero- or food allergens, and extremes of heat, cold, or humidity.44 In mild AD, treatment involves as-needed use of low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS); in moderate- to-severe AD, a mid-potency TCS should be regularly used. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) (pimecrolimus or tacrolimus) and crisaborole are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved alternatives. Topical anti-inflammatory medications can be used either proactively (1 to 2 times daily or weekly, depending on the agent and its potency) or 1 to 2 times daily as needed for flares. Patients with severe or nonresponsive disease should be referred to an allergist or dermatologist. These patients may need systemic treatment, such as dupilumab or systemic immunosuppressants. Chronic or recurrent use of systemic corticosteroids is not recommended, but these medications may serve as bridge therapies to more appropriate, long-term treatment. Alternative treatments for moderate-to-severe AD include phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,37

FIGURE 2.

Step-care management of atopic dermatitis (AD). Acute and maintenance treatments for atopic dermatitis across the spectrum of disease severity. FDA, Food and Drug Administration; TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor; TCS, topical steroid. aNot an indicated dosage. bFor patients aged ≥2 years with mild-to-moderate AD. cFor adults (aged ≥18 years) or adolescents (aged 12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. dNot FDA-approved for AD. eNot recommended for long-term maintenance. (Adapted from Boguniewicz et al with permission from Elsevier.37)

Crisaborole and dupilumab are the first new classes of anti-inflammatory medications for AD to be FDA approved since TCI’s approval nearly 20 years ago. Crisaborole was approved in December 2016 for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and older.45 Dupilumab was approved for adults (aged ≥18 years) and adolescents (aged 12-17 years) in March 2017 and March 2019, respectively, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD that has not adequately responded to topical prescription therapies, or when such therapies are not advisable.46,47

CRISABOROLE: MECHANISM OF ACTION AND KEY CLINICAL TRIALS

Crisaborole is a nonsteroidal topical ointment that inhibits the activity of phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4), an intracellular mediator of inflammation that degrades cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).48 PDE-4 activity is elevated in various types of circulating immune cells in patients with AD. Decreases in cAMP lead to production and release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (eg, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-31) thought to contribute to the manifestations of AD.49–52 Thus, crisaborole may reduce inflammation by inhibiting PDE4, which leads to a decrease in cytokine production.53

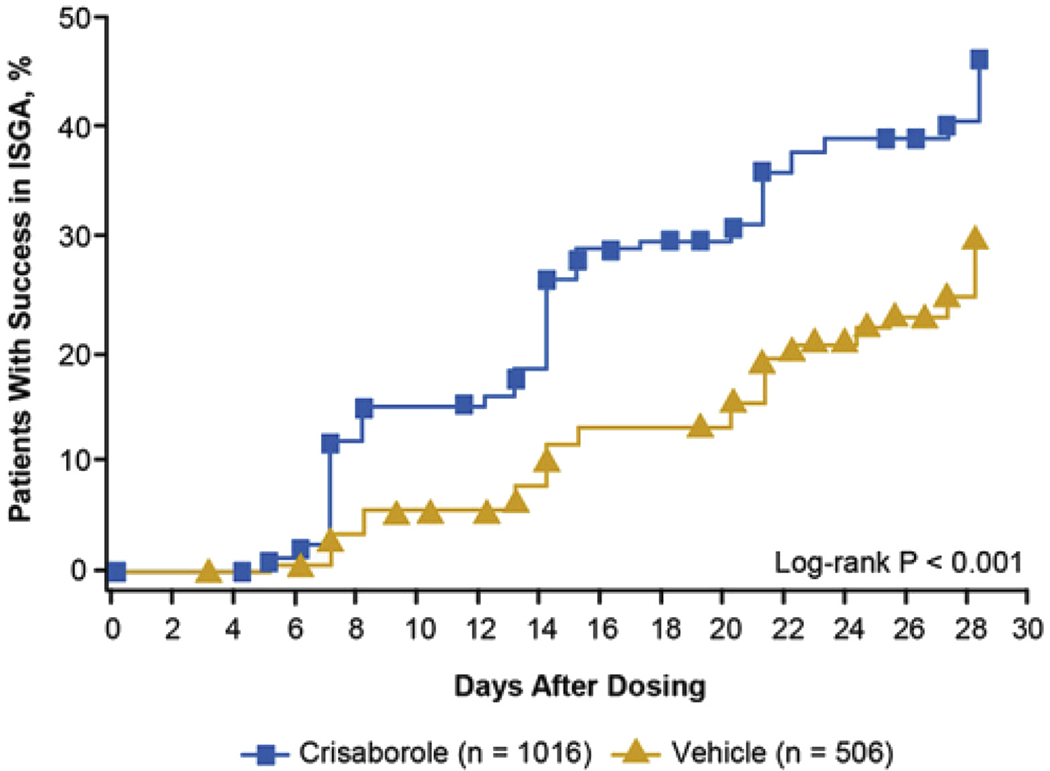

Clinical trials leading to crisaborole’s FDA approval for AD include AD-301 and AD-302—two phase 3, vehicle-controlled, double-blind studies that enrolled 1527 patients with mild-to-moderate AD aged 2 years and older.54 The trials were identical in design. Patients were treated with study drug or vehicle control twice daily for 28 days, with a primary endpoint of clear (0) or almost clear (1) and a 2-grade or greater improvement from baseline on the Investigator’s Static Global Assessment. Results showed that more patients in the crisaborole group than in the vehicle group achieved the primary endpoint at day 29 (32.8% vs 25.4% in AD-301 and 31.4% vs 18.0% in AD-302).54 Despite a strong vehicle effect, these differences were statistically significant (P = .038 and P < .001 for AD-301 and AD-302, respectively). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients on crisaborole achieved the primary outcome significantly more quickly than those treated with vehicle (Figure 3; P < .001). They also experienced improvements in pruritus sooner than did patients in the control group (pooled data, 1.37 vs 1.70 days, P = .001). Adverse events were infrequent, with the most common being application-site pain affecting 4.4% of patients on crisaborole compared with 1.2% of controls (P = .001).54 Anecdotally, application-site stinging and burning may occur more frequently in daily clinical practice than has been observed in clinical trials; thus, assessing tolerability is an important aspect of crisaborole selection and adherence among patients with AD.

FIGURE 3.

Patients achieving success in ISGA with crisaborole in AD-301 and AD-302. Kaplan-Meier analysis shows that patients treated with crisaborole achieved the studies’ primary endpoint (of clear [0] or almost clear [1] and a ≥2-grade improvement from baseline on the ISGA) sooner than did those treated with vehicle ointment (P <.001). AD, Atopic dermatitis; ISGA, Investigator’s Static Global Assessment. (Reprinted from Paller et al with permission from Elsevier.54)

DUPILUMAB: MECHANISM OF ACTION AND KEY CLINICAL TRIALS

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-4 receptor alpha-chain subunit common to IL-4 and IL-13 receptors. IL-4 and IL-13 are integral to TH2-mediated inflammation and associated skin changes in AD,55 and levels of both cytokines have been correlated with AD disease activity.56,57 Studies have documented numerous effects for dupilumab potentially contributing to skin normalization, including downregulation of inflammatory mediators, downregulation of markers of epidermal proliferation, and upregulation of genes involved in skin barrier function.58,59

Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in the treatment of AD has been demonstrated in numerous clinical trials, key among them the phase 3 SOLO-1, SOLO-2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS, and AD-1526 trials. SOLO-1 and SOLO-2 were identically designed, placebo-controlled clinical trials that together enrolled 1379 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate responses to topical therapy.60 Patients were randomized to subcutaneous (SC) injections with dupilumab (300 mg) once weekly, placebo once weekly, or dupilumab (300 mg) alternating every other week with placebo. Patients did not routinely use TCS during the trial, but if they required rescue TCS, they were allowed to continue participating. The primary outcome was a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) and a reduction from baseline to 16 weeks of ≥2 points in that score. Other outcomes included a 75% improvement from baseline in EASI score (EASI 75), reduction in pruritus, reduction in symptoms of anxiety or depression, and improvement in QOL.

In SOLO-1, 37% of patients on once-weekly dupilumab and 38% of those on biweekly dupilumab achieved the primary outcome, compared with 10% on placebo (P < .001 for both regimens vs placebo).60 Findings from SOLO-2 were similar.60 In addition, SOLO-1 and SOLO-2 showed improvement in EASI-75 with both dupilumab regimens (44% to 52% for dupilumab vs 12% to 15% for placebo, P < .001 vs placebo for all comparisons); furthermore, dupilumab treatment was associated with reductions in pruritus and depression or anxiety as well as improvements in QOL (all significant relative to placebo).60 Regarding adverse events, injection site reactions and conjunctivitis (including allergic conjunctivitis and conjunctivitis of unspecified cause) occurred more frequently with dupilumab than placebo.60

The LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial assessed the efficacy of dupilumab (300 mg weekly or every other week) versus placebo in 740 adults with AD on background TCS.61 The trial ran 52 weeks and had 2 primary efficacy endpoints: percent of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 and ≥2-point improvement from baseline, and EASI-75 improvement. Similar to SOLO-1 and SOLO-2, at week 16, both dupilumab regimens showed improvements on primary outcomes (39% for each) compared with placebo (12%) at week 16, findings that were significant (P < .0001) and maintained at 52 weeks. As for SOLO-1 and SOLO-2, the most common adverse events seen with dupilumab were injection site reactions and conjunctivitis.61 These findings confirm longer-term safety and efficacy of dupilumab when combined with TCS.

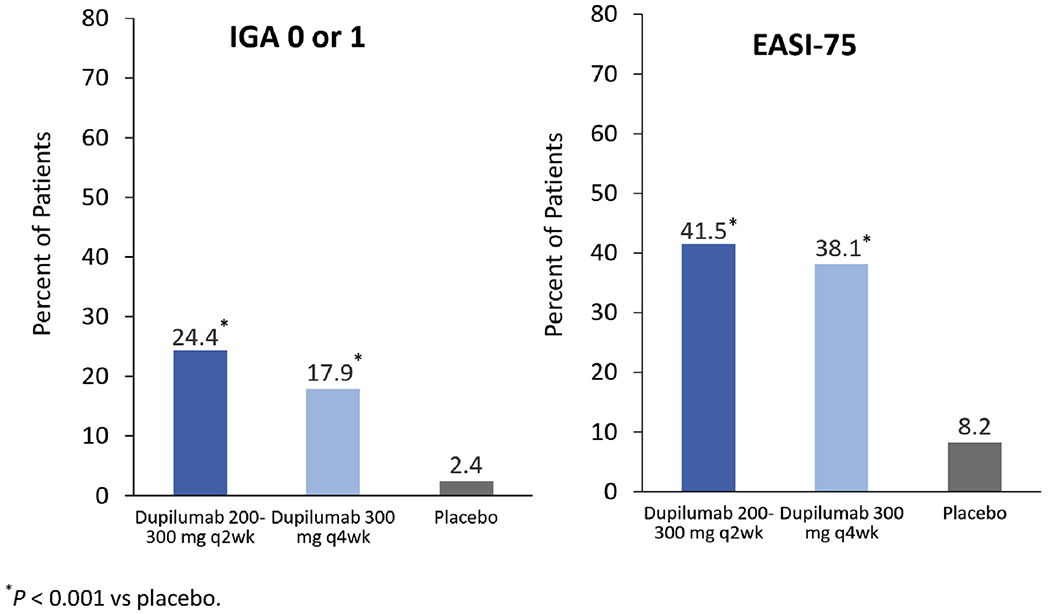

AD-1526 studied dupilumab in adolescents (aged 12-17 years) whose AD was inadequately controlled with topical treatments.62 In this trial, 251 patients were randomized to placebo, dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks, or dupilumab 200 mg or 300 mg (based on weight <60 kg or ≥60 kg, respectively) every 2 weeks. There were 2 primary outcomes, both assessed at week 16: the percentage of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 and the percentage of patients achieving EASI-75. All dupilumab regimens had significant efficacy relative to placebo (P < .001) (Figure 4), with a trend of higher percentages seen with the more frequent, weight-based dosing regimen.62 Safety findings in adolescents were similar to those in adults, with approximately 10% or less experiencing injection site reactions and conjunctivitis on study drug compared with less than 5% on placebo.62

FIGURE 4.

AD-1526: dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD in AD-1526.62 Dupilumab was significantly more effective than control for both primary endpoints (percentage achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 and percentage achieving EASI-75). AD, Atopic dermatitis; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment.

EMERGING THERAPIES IN ATOPIC DERMATITIS

An array of topical, oral, and injectable therapies targeting specific disease pathways in AD are in development for pediatric and adult populations.63,64 Among newer targets currently being investigated are various inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-22, IL-31) or their receptors; Janus kinase (JAK), which mediates downstream effects for multiple inflammatory cytokines; and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1, an ion channel implicated in pruritus. In particular, 2 injectable anti-IL-13 agents (tralokinumab and lebrikizumab) are showing promise in phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trials,65,66 as are several oral anti-JAK agents (eg, abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib).67–69 Table IV summarizes these and other agents in development, grouped according to target.63–75

TABLE IV.

| Target | Compound | Route of administration | AD population(s) | Clinical trials phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor | Tapinarof (GSK2894512) | Topical | Adolescents | 2 |

| Adults | ||||

| IL-13 | Lebrikizumab | SC injection | Adults | 2 |

| Tralokinumab | SC injection | Adolescents | 3 | |

| Adults | ||||

| IL-31 receptor | Nemolizumab | SC injection | Adults | 2 |

| JAK | Abrocitinib | Oral | Adults | 3 |

| Adolescents | ||||

| Baricitinib | Oral | Adults | 3 | |

| Delgocitinib | Topical | Children | 1, 2 | |

| Adolescents | ||||

| Adults | ||||

| Ruxolitinib | Topical | Adults | 1, 3 | |

| Adolescents | ||||

| Upadacitinib | Oral | Children | 1, 3 | |

| Adolescents | ||||

| Adults | ||||

| PDE-4 | OPA-15406 | Topical | Children | 2 |

| Adults | ||||

| RVT-501 | Topical | Children | 1, 2 | |

| Adults | ||||

| TRPV1 receptor | PAC-14028 | Topical | Children | 1-3 |

| Adults | ||||

| TSLP | Tezepelumab | SC injection | Adults | 2 |

AD, Atopic dermatitis; JAK, Janus kinase; PDE, phosphodiesterase; SC, subcutaneous; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

CONCLUSIONS

AD is common in infants and young children, may persist through the lifespan, and may signal the onset of allergies and criteria for asthma later in life. AD in adults may be childhood-onset or adult-onset, with a more heterogeneous presentation in adulthood that can make diagnosis challenging. In both children and adults, proper diagnosis that excludes conditions with similar skin manifestations, together with assessment of AD severity, is crucial to selecting appropriate treatment and achieving control of the intense itch and rash that can disrupt sleep, contribute to depression and anxiety, and impair QOL. Two newer treatments that target specific disease pathways (crisaborole and dupilumab) are now FDA approved. Crisaborole is a good low-potency option for patients with AD, but the associated burning and stinging often limits its use, and it is not indicated for severe AD. In contrast, dupilumab is an excellent, highly effective option for adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe AD. More treatments are on the way, offering relief and hope to patients and caregivers.

SIDEBARS

Case 1: “Eddie F” –classic infant-onset atopic dermatitis

Eddie is a 6-month-old baby boy with a persistent itchy rash affecting his hands, feet, and knees bilaterally (Figure 5) as well as his face. He has been referred by his pediatrician for likely AD and possible allergies. He has been exclusively breast-fed, and his mother says she has tried eliminating various foods from her diet with no improvement in the rash. His father has a history of allergic rhinitis. There is otherwise no family history of AD or other atopic diseases. The parents have tried aggressive moisturizing and over-the-counter hydrocortisone to treat the rash, and they seem to help. Still, Eddie scratches constantly and has difficulty sleeping.

FIGURE 5.

Case 1: “Eddie F.” Appearance of the pruritic rash affecting Eddie’s hands, feet, and knees. His face is also affected. Photo courtesy of Peck Y. Ong.

Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis.

Use of the United Kingdom Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis35 (Table V) confirms probable AD, and differential diagnostic considerations rule out other possible causes for the rash, including contact dermatitis (lack of characteristic anatomical distribution, eg, in the diaper area), viral exanthems (rash is chronic, not acute), and immune deficiency–associated skin conditions (rash was not present at birth). Skin testing for peanut allergy was negative.

TABLE V.

Eddie’s diagnosis using the UKWP criteria35

| Must have: | |

| An itchy skin condition in the last 12 mo | ☑ |

| Plus 3 or more of: | |

| Onset age <2 y (not used for children <4 y) | □ |

| History of flexural involvement | ☑ |

| History of generally dry skin | ☑ |

| Personal history of other atopic disease, or in children aged <4 y, history of atopic disease in a first-degree relative |

☑ |

| Visible flexural dermatitis | ☑ |

UKWP, United Kingdom Working Party.

Assessment of severity and selection of treatment.

Eddie’s mother completes the POEM for Children (Figure 6),40 providing a score of 17 that categorizes Eddie’s AD as severe.

FIGURE 6.

Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)40 Score for Eddie. The POEM for children, as completed by Eddie’s mother. Reprinted with permission from The University of Nottingham (nottingham.ac.uk/go/poem).

Recommended treatment includes basic skin management (frequent moisturization, daily warm baths) along with TCS of at least medium potency and use of wet wrap therapy to get the rash under control (Figure 2). At a follow-up appointment 3 months later, Eddie’s skin was mostly clear (POEM score of 2).

Eddie’s AD remains mostly under control throughout childhood, with the use of mid-potency TCS and occasional use of crisaborole on his hands and face. However, at age 13, he presents with severe generalized eczema that also affects the flexural regions of his elbows, hands, and knees. A TCI—tacrolimus ointment 0.03%—is added to his regimen. POEM assessments over multiple clinic visits show scores of approximately 20 despite the consistent use of mid-potency TCS and TCI. Dupilumab was therefore considered. (Patch testing could not be performed to rule out contact dermatitis due to the extent of the rash on his back and concerns about stopping TCS and TCI to perform the test.) Eddie expresses apprehension about injections, but agrees to give it a try. On the basis of his weight (45 kg), he starts with two 200 mg SC injections (400 mg total), and then continues with an SC injection of 200 mg every other week.76 At 3-month follow-up, the rash has mostly disappeared, and he reports no side effects except transient injection-site pain. At 6- month follow-up, his skin is clear.

Case 2: “Diana K” –adult-onset atopic dermatitis (adapted from Silverberg29)

Diana is a 68-year-old woman who presents with an itchy rash affecting her antecubital fossae (Figure 7, A), neck (Figure 7, B), and much of the rest of her body. The rash first appeared on her face when she was 38 years old and was at first mild and intermittent, but over time became more severe and persistent, and widespread. Initially, it was responsive to TCS, but now, even with careful basic skin care (baths and moisturizing) and use of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment, she rates her itch as 10/10 and her pain as 6/10, and she is having difficulty sleeping. Diana’s history includes asthma starting at age 35 years and seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis starting at age 51 years. She has no food allergies and no memory of eczema or skin sensitivity in childhood.

FIGURE 7.

Case 2: “Diana K.” Appearance of possible atopic dermatitis at presentation. A, Flexural erythema and lichenification affecting the antecubital fossa. B, Erythema and rash affecting the neck. (Reprinted from Silverberg with permission from The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.29)

Diagnosis and assessment of severity.

Skin examination reveals erythematous patches and plaques with lichenification on the antecubital and popliteal fossae, wrists, and ankles; moderate-to-severe lesions on the dorsal and palmar hands and digits; severe erythema on the face, neck, and chest; and generalized pink, poorly demarcated patches and plaques on the back and abdomen. Punch biopsies reveal epidermal spongiosis and findings relevant to Diana’s lesions, and laboratory testing perivascular infiltrates and eosinophils in the superficial dermis—revealed no clear-cut underlying medical disorders. She states that all consistent with eczematous reactions. Patch testing revealed no the rash worsens with stress and cold weather. Her symptoms and history meet the H-R criteria for diagnosis of AD (Table I). Other findings rule out alternate diagnoses, and her PO-SCORAD score documents her AD as severe.

Treatment.

On the basis of its relative efficacy and safety, Diana starts dupilumab treatment, beginning with two 300 mg SC injections (600 mg total), followed by 300 mg SC injection every other week.76 She continues her triamcinolone ointment as needed and daily skin care regimen. Her lesions and itch clear gradually over 16 weeks. She reports mild injection site pain and mild conjunctivitis that subsides with the use of lubricant eye drops; however, a referral to an ophthalmologist was provided. At a 6-month follow-up, she shows no evidence of relapse. She remains on maintenance treatment with dupilumab and triamcinolone.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Abbreviations used

- ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- EASI

Eczema Area and Severity Index

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- H-R

Hanifin-Rajka

- HIES

Hyper-IgE syndrome

- IGA

Investigator Global Assessment

- JAK

Janus kinase

- PDE-4

Phosphodiesterase-4

- PO-SCORAD

Patient-Oriented SCORAD

- POEM

Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure

- QOL

Quality of life

- SC

Subcutaneous

- SCORAD

SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

- TCI

Topical calcineurin inhibitor

- TCS

Topical corticosteroids

- TH2

T helper 2

- UKWP

United Kingdom Working Party

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: J. I. Silverberg has served as a consultant for AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Asana BioSciences, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kiniksa, Leo Pharma, and Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. P. Y. Ong has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Inc.; and has done contract research with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest. The planners, reviewers, editors, staff, CME committee, or other members at The France Foundation who control content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, Boguniewicz M, Beck L, LeBovidge J, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boguniewicz M Atopic dermatitis: the updated practice parameter and beyond. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014;35:429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70: 338–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, Krol A, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:116–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:327–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanifin JM, Reed ML, Eczema Prevalence and Impact Working Group. A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. J Amer Acad Derm 2007;18:338–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, et al. , Multicenter Allergy Study Group. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ, Jaron AG. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HH, Patel KR, Singam V, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and phenotype of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:1526–1532.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;121:340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolis JS, Abuabara K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150:593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvador S, Romero-Pérez D, Encabo-Durán B. Atopic dermatitis in adults: a diagnostic challenge. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2017;27:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gochnauer H, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Cardwell L, Anolik RB. The psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1027:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:428–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, et al. Symptoms and diagnosis of anxiety and depression in atopic dermatitis in U.S. adults. Br J Dermatol 2019;181:554–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li JC, Fishbein A, Singam V, Patel KR, Zee PC, Attarian H, et al. Sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. Dermatitis 2018;29:270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, Boor P, Sheldon S, Zee P, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugarman JL. The epidermal barrier in atopic dermatitis. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2008;27:108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czarnowicki T, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Skin barrier and immune dysregulation in atopic dermatitis: an evolving story with important clinical implications. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.David Boothe W, Tarbox JA, Tarbox MB. Atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1027:21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czarnowicki T, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Novel concepts of prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis through barrier and immune manipulations with implications for the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139: 1723–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran MM, Lefebvre DL, Dharma C, Dai D, Lou WYW, Subbarao P, et al. , Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development Study investigators. Predicting the atopic march: results from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:601–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkin MR, Strachan DP, Williams HC, Kennedy CT, Golding J, Team AS. Natural history of atopic dermatitis and its relationship to serum total immunoglobulin E in a population-based birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2004;15:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krol A, Krafchik B. The differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in childhood. Dermatol Ther 2006;19:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberting CL, Davis J, Puck JM, Holland SM, Turner ML. Dermatitis and the newborn rash of hyper-IgE syndrome. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergerson JRE, Freeman AF. An update on syndromes with a hyper-IgE phenotype. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2019;39:49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Su HC. Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndromes in pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr 2011;23:653–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverberg JI. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisshaar E, Weiss M, Mettang T, Yosipovitch G, Zylicz Z, Special Interest Group of the International Forum on the Study of Itch. Paraneoplastic itch: an expert position statement from the Special Interest Group (SIG) of the International Forum on the Study of Itch (IFSI). Acta Derm Venereol 2015;95: 261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summers EM, Bingham CS, Dahle KW, Sweeney C, Ying J, Sontheimer RD. Chronic eczematous eruptions in the aging: further support for an association with exposure to calcium channel blockers. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:814–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sung CT, McGowan MA, Jacob SE. Allergic contact dermatitis evaluation: strategies for the preschooler. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2018;18:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19: 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1980;92(Suppl):44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, Archer CB, Shipley MJ, Hunter JJ, et al. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994;131: 383–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gooderham MJ, Hong CH, Albrecht L, Bissonnette R, Dhadwal G, Gniadecki R, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. J Cutan Med Surg 2018; 22(Suppl):3S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol 1993;186:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The Eczema Area And Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol 2001;10:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The Patient-oriented Eczema Measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140:1513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stalder JF, Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, Holm EA, De Raeve L, Seidenari S, et al. , PO-SCORAD Investigators Group. Patient-Oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD): a new self-assessment scale in atopic dermatitis validated in Europe. Allergy 2011;66:1114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolkerstorfer A, de Waard van der Spek FB, Glazenburg EJ, Mulder PG, Oranje AP. Scoring the severity of atopic dermatitis: three item severity score as a rough system for daily practice and as a pre-screening tool for studies. Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:356–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverberg JI, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, Ong PY, et al. Validation of five patient-reported outcomes for atopic dermatitis severity in adults [published online ahead of print April 10, 2019]. Br J Dermatol. 10.1111/bjd.18002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverberg NB. Atopic dermatitis prevention and treatment. Cutis 2017;100:173.177; 192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Eucrisa for eczema. December 14, 2016. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-eucrisa-eczema. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 46.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new eczema drug Dupixent. March 28, 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-eczema-drug-dupixent. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 47.FDA OKs Dupilumab Indication for Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis. Pharmacy Times. March 11, 2019. Available from: https://www.specialtypharmacytimes.com/news/fda-oks-dupilumab-indication-for-adolescents-with-atopic-dermatitis. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- 48.Baumer W, Hoppmann J, Rundfeldt C, Kietzmann M. Highly selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for the treatment of allergic skin diseases and psoriasis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2007;6:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grewe SR, Chan SC, Hanifin JM. Elevated leukocyte cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase in atopic disease: a possible mechanism for cyclic AMP-agonist hyporesponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1982;70:452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker CW, Kennedy S, Eisen AZ. Leukocyte and lymphocyte cyclic AMP responses in atopic eczema. J Invest Dermatol 1977;68:302–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gantner F, Gotz C, Gekeler V, Schudt C, Wendel A, Hatzelmann A. Phosphodiesterase profile of human B lymphocytes from normal and atopic donors and the effects of PDE inhibition on B cell proliferation. Br J Pharmacol 1998; 123:1031–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan SC, Reifsnyder D, Beavo JA, Hanifin JM. Immunochemical characterization of the distinct monocyte cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase from patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993;91:1179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanifin JM, Chan SC, Cheng JB, Tofte SJ, Henderson WR Jr, Kirby DS, et al. Type 4 phosphodiesterase inhibitors have clinical and in vitro anti-inflammatory effects in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, Blumenthal RL, Boguniewicz M, Call RS, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;75:494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamilton JD, Suarez-Farinas M, Dhingra N, Cardinale I, Li X, Kostic A, et al. Dupilumab improves the molecular signature in skin of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:1293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamid Q, Naseer T, Minshall EM, Song YL, Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. In vivo expression of IL-12 and IL-13 in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98:225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamid Q, Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Differential in situ cytokine gene expression in acute versus chronic atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 1994;94:870–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guttman-Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B, Suárez-Fariñas M, Ardeleanu M, Esaki H, et al. Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143: 155–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim BE, Leung DYM. Significance of skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2018;10:207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2335–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:2287–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Pariser DM, Blauvelt A. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 study. 27th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; September 12-16, 2018 Paris, France: Available from: https://investor.regeneron.com/static-files/a4747df7-46a9-4765-b7e9-387bff43428e. Accessed August 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF, Simpson EL, Irvine AD. Assessing the new and emerging treatments for atopic dermatitis. Sem Cutan Med Surg 2016;35:S92–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson BB, Franco AI, Beck LA, Prezzano JC. Treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2019;12: 181–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wollenberg A, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Kell C, Ranade K, et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti-IL-13 mAb. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simpson EL, Flohr C, Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Sofen H, Taïeb A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:863–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, Forman SB, Wilke A, Prescilla R, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beck L, Hong C, Hu X, Chen S, Calimlim B, Teixeira H, et al. Upadacitinib effect on pruritus in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis; from a phase 2b randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;121: S21. [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. Study to evaluate efficacy and safety of PF-04965842 with or without topical medications in subjects aged 12 and older with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (JADE-EXTEND). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03422822. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- 70.Peppers J, Paller AS, Maeda-Chubachi T, Wu S, Robbins K, Gallagher K, et al. A phase 2, randomized dose-finding study of tapinarof (GSK2894512 cream) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. JAK-1 inhibitor atopic dermatitis adolescents (JADE-TEEN). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03796676. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- 72.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. Dose-ranging trial to evaluate delgocitinib cream 1, 3, 8, and 20 mg/g compared to delgocitinib cream vehicle of an 8-week dose-ranging treatment period in adult subjects with atopic dermatitis. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03725722. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 73.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. Delgocitinib cream for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis during 8 weeks in adults, adolescents, and children. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03826901. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 74.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. TRuE AD1: an efficacy and safety study of ruxolitinib cream in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03745638. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- 75.National Institutes of Health. US National Library of Medicine. TRuE AD2: an efficacy and safety study of ruxolitinib cream in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03745651. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- 76.Dupixent [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; March 2019. US Food and Drug Administration; FDA approves new eczema drug Dupixent March 28, 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-eczema-drug-dupixent. Accessed May 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]