Abstract

KRAS homo-dimerization has been implicated in the activation of RAF kinases, however, the mechanism and structural basis remain elusive. We developed a system to study KRAS dimerization on nanodiscs using paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR, and determined distinct structures of membrane-anchored KRAS dimers in the active GTP- and inactive GDP-loaded states. Both dimerize through an α4-α5 interface, but the relative orientation of the protomers and their contacts differ substantially. Dimerization of KRAS-GTP, stabilized by electrostatic interactions between R135 and E168, favours an orientation on the membrane that promotes accessibility of the effector-binding site. Remarkably, ‘cross’-dimerization between GTP- and GDP-bound KRAS molecules is unfavorable. These models provide a vital platform to elucidate the structural basis of RAF activation by RAS and to develop newer inhibitors that can disrupt the KRAS dimerization. The methodology developed to specifically probe the intermolecular interactions within KRAS dimer is applicable to many other farnesylated small GTPases.

Keywords: Dimerization, Membrane Proteins, NMR Spectroscopy

Graphical Abstract

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR approaches combined with a nanodisc system reveal distinct structures of membrane-associated homodimers of GTP- versus GDP-bound KRAS4B. Both structures dimerize via an interface comprising α4-α5, but differ in the relative orientation of the protomers. KRAS4B-GTP dimerization increases the accessibility of the effector binding site for RAF kinases.

Introduction

RAS GTPases act as binary molecular switches that cycle between the active GTP- and inactive GDP-bound states, dynamically regulating multiple signal transduction pathways for cell proliferation and survival[1]. Notably, gain-of-function mutations of KRAS have been recognized as some of the most prevalent oncogenic drivers, occurring in approximately 30% of all human cancers, primarily pancreatic, colon and lung cancers[2]. Recent data have reinvigorated a hypothesis that transient RAS dimers at the plasma membrane could serve as the functional unit to recruit and activate RAF[3]. In this respect, disruption of KRAS dimers has emerged as an alternative anticancer therapeutic strategy, as targeting KRAS by more conventional approaches has been very challenging[4]. However, it has been a challenge to determine high-resolution structures of RAS dimers on a membrane. To date, the vast majority of crystallographic studies have focused on the highly conserved GTPase domains of RAS isoforms (H-, K-, and N-RAS), which lack the disordered C-terminal hypervariable region (HVR) responsible for membrane association, and thus provide limited insight into membrane-dependent RAS dimerization. Several molecular dynamics (MD) studies have proposed RAS dimer structures with a variety of interfaces involving the α3-α4, α4-α5 or β-sheet regions[5]. This lack of agreement warrants rigorous experimental determination of the structures of the membrane-bound RAS dimers.

Here, we utilized paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR experiments to construct a data-driven structure of a transient KRAS dimer on a lipid-bilayer nanodisc encircled by two copies of membrane scaffold protein 1D1 (MSP1D1). This nanodisc contains 20% unsaturated phosphatidylserine lipid to mimic the membrane that promotes KRAS dimerization[6]. PRE experiments have been developed as highly sensitive tools for the visualization of sparsely populated, transient or low affinity complexes[7]. Nanodiscs provide a homogeneous, stable, soluble native-like membrane that can be prepared with well-defined lipid mixtures using MSP (as performed here)[8], or alternatively native membrane fragments and associated proteins can be captured using styrene maleic acid (SMA) co-polymers[9]. To identify the interfaces that mediate KRAS dimerization and the interactions between the dimer and the membrane, we introduced a variety of PRE tags, including TEMPO nitroxide tags on the KRAS protein, Gd3+ and Cu2+ ions chelated by DTPA attached to lipid head groups, as well as free soluble Gd-DTPA-BMA complex (Figure 1).

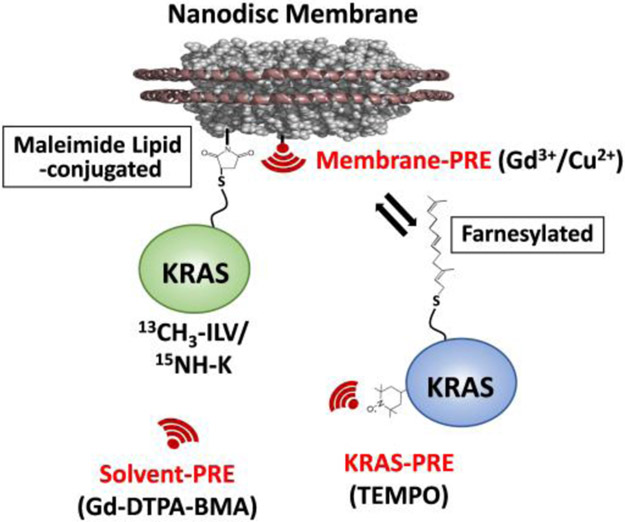

Figure 1.

Experimental design of nanodisc-based system for paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) studies of membrane-dependent KRAS dimerization. 13C- and 15N-labeled KRAS is irreversibly attached to the lipid bilayer of a nanodisc by linking Cys185 (the site of farnesylation in native KRAS) to a DOPE head group through maleimide conjugation (MC-KRAS). These nanodiscs are then titrated with isotopically unlabeled, farnesylated and fully processed KRAS (FP-KRAS). PRE spin labels including (i) TEMPO nitroxide tags attached to specific Cys residues of FP-KRAS, (ii) Gd3+/Cu2+ ions chelated by a DTPA-modified lipid head group, and (iii) Gd-DTPA-BMA in the bulk solvent are used to identify dimerization and membrane interfaces.

Results

KRAS Dimerizes on Membrane Surface through α4-α5 Interface.

We first carried out NMR experiments to examine whether fully processed KRAS4B (FP-KRAS), the C-terminally farnesylated and carboxy-methylated form, self-associates on a membrane, and to identify relevant interfaces. In the presence of nanodiscs, FP-KRAS that is selectively isotopically labeled with 13C on Ile, Leu, Val, and Thr (ILVT) was mixed with an equivalent amount of isotopically unlabeled FP-KRAS. Experiments were performed with FP-KRAS bound to either GDP or the non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue GTPγS. The 1H-13C TROSY spectra exhibited no obvious chemical shift perturbations (CSP) nor large peak intensity changes upon addition of the unlabeled protein (Figure S1). Both 13C-labeled and unlabeled FP-KRAS exist in equilibrium between free in solution and nanodisc-associated states, which exchange freely (KD for membrane association is in the micromolar range[10]). Thus, the stronger NMR signals from freely diffusing FP-KRAS in solution may obscure signals from the population of nanodisc-bound FP-KRAS dimers.

To overcome this challenge, we employed a maleimide-conjugated KRAS (MC-KRAS) system, in which Cys185 is irreversibly conjugated to the reactive maleimide moiety of a PE-MCC lipid preassembled in nanodiscs, as previously described[11]. The double alkyl chains of this lipid moiety are expected to have substantially higher affinity for the lipid bilayer than farnesyl. To observe dimerization, MC-KRAS was isotopically 13C-labeled at single methyl groups in Ile, Leu, and Val (ILV, Cδ1, Cδ and Cγ, respectively), as well as 15N-labeled at the amide group in Lys. The isotopically labeled, nanodisc anchored MC-KRAS was mixed with an equivalent amount of FP-KRAS that was tagged with a TEMPO spin label at one of three solvent-exposed cysteines (Cys118, Cys169, or Cys39). Cys118 and Cys169 are positioned at the periphery of the α4-α5 surface, and Cys39 is located on β2 in the effector binding site. The advantages of combining FP- and MC-KRAS are described in detail in Figure S2.

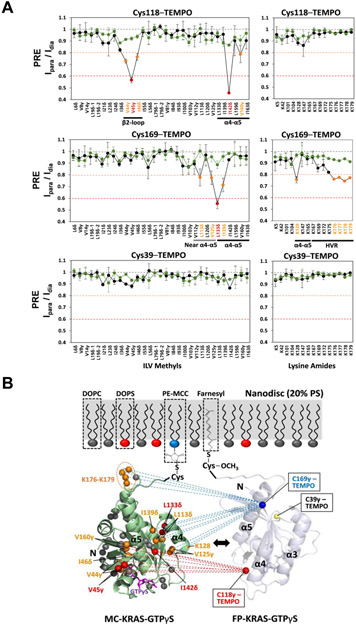

The intensity ratios of cross peaks from the isotopic probes before versus those after the spin label was quenched by reduction (Ipara/Idia) were analyzed. The PRE effects on the ILV methyl and Lys amide probes of MC-KRAS were plotted by residue, for both the GTPγS- and GDP-bound states (Figure 2 and S3). The PRE data obtained from MC-KRAS-GTPγS with addition of FP-KRAS-GTPγS bearing a TEMPO spin label at Cys118 show measurable PRE effects in the α4-α5 region and an adjacent β2-loop region. FP-KRAS-GTPγS labeled with TEMPO at Cys169 induced PRE effects in and near the α4-α5 region as well as lysines (K176-K179) in the HVR. Overall, these results revealed a dimer interface in which the PRE-affected residues within and surrounding the α4-α5 region are spatially close to TEMPO-labeled Cys118 and Cys169, which are located on the edges of the α4-α5 surface of the opposing protomer (Figure 2B). In contrast, in analogous experiments performed without nanodiscs, no PRE-induced spectral changes were apparent, regardless of the nucleotide bound (Figure S4), demonstrating that KRAS dimerization is membrane-dependent.

Figure 2.

Intermolecular PRE effects between KRAS-GTPγS molecules. (A) Intensity ratios of peaks in the presence of paramagnetic versus diamagnetic (reduced) spin labels (Ipara/Idia) for ILV 13C-methyls and Lys 15N-amides of MC-KRAS-GTPγS in the presence of FP-KRAS-GTPγS (‘homo-dimerization’, black lines) and FP-KRAS-GDP (‘cross-dimerization’, green lines) bearing TEMPO labels at one of Cys118, Cys169, or Cys39. Probes are categorized according to the extent of PRE (Ipara/Idia threshold values < 0.8, moderate, yellow and < 0.6, strong, red). (B) Mapping PRE-affected probes onto the crystal structure of KRAS-GTPγS (PDB ID: 4DSO). Probes that exhibit moderate and strong PREs are colored as in panel (A), and PRE-unaffected probes are gray. Dotted lines represent PRE effects that arise from TEMPO conjugated to Sγ atoms of Cys118 (red) and Cys169 (blue) in the opposing (arbitrarily positioned) FP-KRAS-GTPγS protomer.

Interestingly, the PRE profiles of MC-KRAS-GTPγS are substantially different from those induced on MC-KRAS-GDP by TEMPO-labeled FP-KRAS-GDP (Figure S3), indicating that the KRAS dimer exhibits distinct nucleotide-dependent conformations on the membrane, although they share a α4-α5 dimer interface. By contrast, FP-KRAS TEMPO-labeled at Cys39 did not cause any appreciable PRE effect on MC-KRAS regardless of the nucleotide bound, demonstrating that the β-sheet effector binding site is not involved in KRAS dimerization. Importantly, no intermolecular PRE effects were observed between GTPγS- and GDP-loaded KRAS molecules, no matter which nucleotide state or residue bears the PRE tag (Figure 2A and S3A). This observation demonstrates that KRAS ‘cross-dimerization’ between different nucleotide-bound states is unfavorable and that the observed PRE is not simply a result of co-localization of protomers on a nanodisc.

The PRE data described above using MC-KRAS are fully consistent with the PRE patterns obtained using isotopically labeled FP-KRAS and TEMPO-labeled FP-KRAS in the presence of nanodiscs (Figure S5 and S6). The magnitude of the PRE effects, however, were smaller than those observed on MC-KRAS, as expected, due to the population of free 13C-FP-KRAS in solution.

Dimerization of KRAS-GTP Increases the Accessibility of the Effector-Binding Site.

To examine the orientation of MC-KRAS with respect to the membrane, we incorporated a small amount of PE-DTPA in nanodiscs, which chelates paramagnetic Gd3+ ions on the lipid head group[11-12], or Lu3+ as a diamagnetic control, assuming that it diffuses freely on the membrane surface and samples the entire surface during the NMR measurements. In order to probe the effect of KRAS dimerization on the interaction of KRAS with the membrane, the Ipara/Idia values for ILV 13C-methyls and Lys 15N-amides of MC-KRAS were measured in the presence or absence of an equivalent concentration of isotopically unlabeled FP-KRAS (Figure 3), which favour the dimeric and monomeric states of KRAS, respectively. In the presence of FP-KRAS, membrane PRE effects arise from a mixture of both states in equilibrium. Each data set was translated into 1H transverse PRE rates (1H-Γ2) using equation 1 in the Material and Methods section, and their 1H-Γ2 ratios (Δ1H-Γ2,di-mono/1H-Γ2,mono) were calculated for each MC-KRAS probe (Figure S7 and S8). In the GTPγS-bound state, PRE increases were observed in the α3-loop region while PRE reductions were shown in the β2-β3 region and in and near the α4-α5 region. In the analogous experiment with the GDP-bound state, PRE increases were observed in α1, the β1-β2-β3 region and the α3-loop region while PRE reductions were shown in and near the α4-α5 region. These results clearly show that in both the GTPγS and GDP states, addition of FP-KRAS to promote dimerization protects the α4-α5 interface from membrane-associated Gd3+ PRE, consistent with this region mediating dimerization of both nucleotide states. However, the concomitant PRE changes on other surfaces suggest that the membrane interfaces may be specific depending on the nucleotide bound.

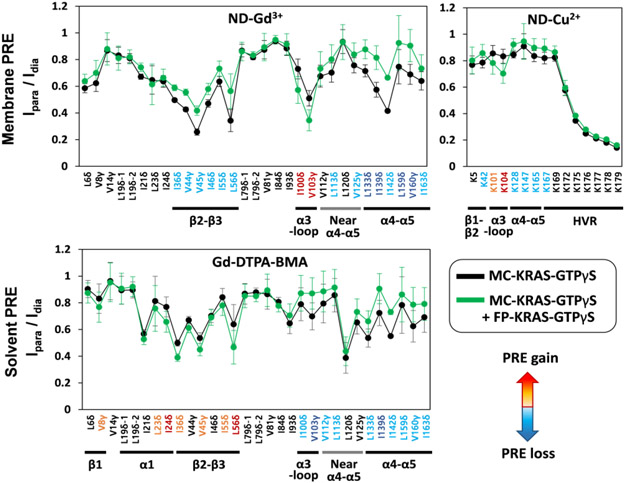

Figure 3.

PRE effects induced by membrane-associated and free soluble spin labels on nanodisc-bound MC-KRAS-GTPγS alone and in the presence of FP-KRAS-GTPγS. The Ipara/Idia values of ILV 13C-methyls and Lys 15N-amides of MC-KRAS-GTPγS were measured with nanodiscs containing 5% Gd3+- or Cu2+-chelated PE-DTPA lipids (as indicated), or with 2 mM Gd-DTPA-BMA in solution, with Lu3+ serving as the diamagnetic control. NMR probes that exhibit increased or decreased PRE upon addition of FP-KRAS-GTPγS are color-coded red or blue, respectively, according to changes in 1H transverse PRE rates of MC-KRAS-GTPγS (see Supporting Figure S7 and S9).

15N-Lys probes were used to monitor the interactions between the HVR and the membrane. Gd3+ induced severe PRE on the HVR, but we detected selective PRE-induced broadening using the weaker paramagnetic ion, Cu2+ [13]. The PRE effects started at residue K172 and were most severe for the five-Lys stretch from K175 to K179 (Figure 3 and S8). This pattern was observed for both monomeric and dimeric states confirming that the basic poly-lysine stretch in the C-terminal HVR is closely associated with the membrane, probably due to electrostatic interactions with the anionic lipid headgroups.

To complement the TEMPO- and Gd3+/Cu2+-PRE data described above, we also performed ‘solvent’ PRE experiments with a paramagnetic co-solute (Gd-DTPA-BMA)[14] to probe potential changes in the solvent-accessible surface of KRAS upon its dimerization (Figure 3, S9, and S10). Upon addition of an equal amount of FP-KRAS to favour dimerization, in both the GTPγS and GDP states, ILV 13C-methyls in the α4-α5 dimer interface and the α3-loop region of MC-KRAS exhibited reduced solvent PRE effects. This result demonstrates that these regions become protected from solvent upon KRAS dimerization on the membrane. Note that either protein-protein or protein-lipid interactions can protect MC-KRAS from solvent PRE. Differences were apparent in the dimerization-induced changes in solvent PRE patterns between the two nucleotide states: the β-sheet effector-binding site exhibits increased PRE in the GTPγS-bound state, indicating that it becomes more exposed to solvent, but this region shows reduced PRE in the GDP-loaded state, indicating protection from solvent in the dimeric state. These solvent PRE effects on the effector-binding site are opposite to the membrane PRE effects, thus both are fully consistent with dimerization of GTPγS-bound KRAS promoting exposure of this region. By contrast, there were no significant dimer-induced changes in PRE on Ile93 located at the middle of α3 helix, suggesting that α3 is not involved in dimerization or membrane binding.

Dissociation Constant for KRAS Dimerization.

The apparent dissociation constant (KD) for dimerization of KRAS on the membrane was estimated by measuring the relative reductions in intensity of peaks [(I0-I)/Io] in one-dimensional spectra for ILV 13C-methyl protons of MC-KRAS on nanodiscs, as increasing amounts of unlabeled FP-KRAS were added (Figure S11). This experiment contains no PRE spin label, rather peak broadening is caused by chemical exchange and increased size of the KRAS-nanodisc complex. The titration data fitted well to a one-site binding model with average KD values of 530 μM and 610 μM for the GTPγS and GDP states, respectively. No intensity reductions were observed when GDP-bound MC-KRAS was titrated with GTPγS-bound FP-KRAS or vice versa (i.e., GTPγS-bound MC-KRAS titrated with GDP-bound FP-KRAS), confirming our finding that cross-dimerization of KRAS is unfavorable. These observations also suggest that FP-KRAS binding to the membrane alone has no influence on the peak intensities of MC-KRAS and that the estimated KD represents homodimerization after FP-KRAS binds to the membrane. As an internal reference, peaks from the lipid aliphatic methyl protons were not influenced by the titrations. The relatively weak affinities for both GTP- and GDP-bound KRAS homodimerization are consistent with the lack of dimerization when they are not attached to membranes.

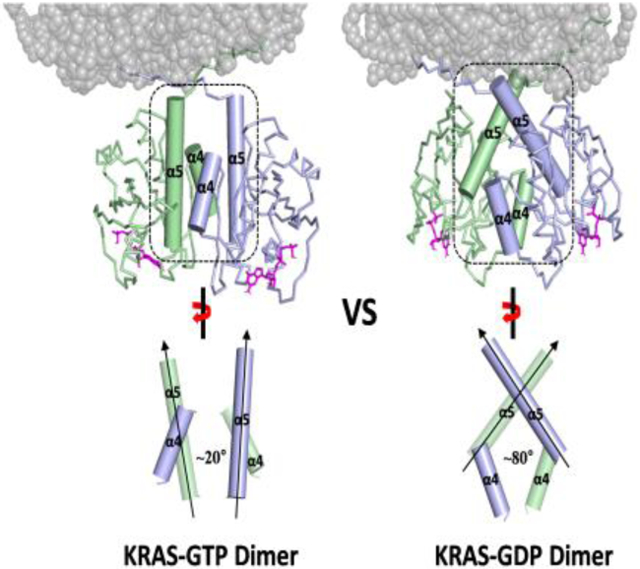

PRE-driven Structures of KRAS Dimers on the Membrane.

Based on the sets of PRE-derived distances between KRAS protomers and between KRAS protomers and membrane (Table S1), we built structural models of KRAS-GTPγS dimers and KRAS-GDP dimers on the nanodisc using the multibody docking protocol in the HADDOCK 2.2 program[15]. The structures of the GTPγS- and GDP-loaded KRAS dimers both exhibit C2 symmetry along axes at the α4-α5 dimer interface. Consistent with the PRE data described above, the HADDOCK-driven models for GTPγS- and GDP-loaded states differ significantly in terms of the relative orientation of the protomers (Figure 4). The interfacial α4 and α5 helices in the representative structures of the KRAS-GTPγS and -GDP dimers are arranged in parallel and perpendicular fashions with angles between the axes of the α5 helices of 19 ± 4° and 79 ± 4°, respectively, for the 20 best models.

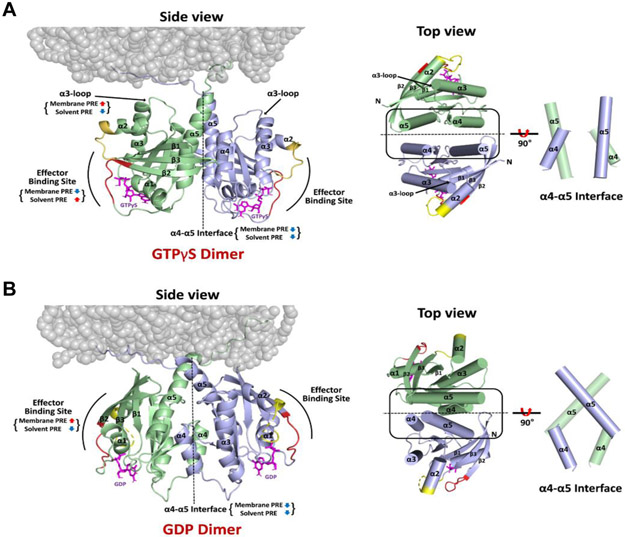

Figure 4.

Structures of membrane-bound KRAS homodimers in the GTPγS-bound (A) and GDP-bound (B) states. Regions that exhibit increased or decreased PRE from membrane or solvent spin labels upon dimerization are indicated, and the switch I and II sites that undergo conformational changes upon GDP/GTP cycling are colored red and yellow, respectively. The right panels highlight the differences in the α4-α5 dimer interfaces between (A) KRAS-GTPγS and (B) KRAS-GDP homodimers, in which the axes of the interfacial α4 and α5 helices are oriented in parallel and perpendicular fashions, respectively.

Most of the final HADDOCK models of KRAS-GTPγS dimers grouped into a cluster, in which the KRAS dimer interacts with the membrane through the HVR, with the C-terminal end of α5, and the α3-loop region in close proximity (Figure 4). The KRAS-GDP dimer also interacts with the membrane surface through the HVR, but is distinct from the KRAS-GTPγS structure in that the C-terminal end of α5 and β1-β2-β3 are most proximal. More details about the HADDOCK models are provided in the Supporting Information (Section 2).

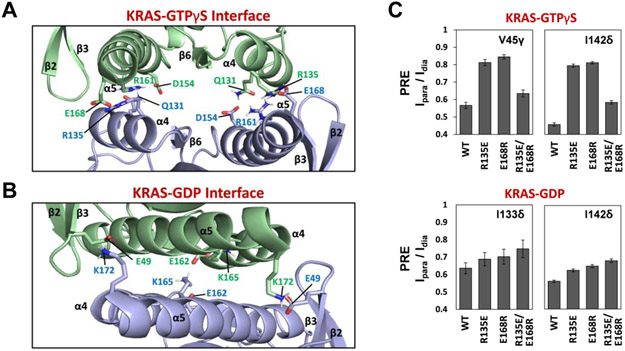

The structure of the KRAS-GTPγS dimer is stabilized mainly by intermolecular interactions between (i) Q131 and D154, (ii) Q131 and R161, and (iii) R135 and E168 (Figure 5A and Table S3). The D154 and R161 sidechains within the same subunit are also intimately proximal and could potentially form a salt-bridge that may be further stabilized by a hydrogen bond with Q131 of the other protomer. In contrast, the KRAS-GDP dimer interface involves different pairs of amino acids sidechains, including two key interactions between (i) E49 and K172 and (ii) E162 and K165 (Figure 5B and Table S4). To validate structural details in the data-driven HADDOCK models, we introduced charge-reversal mutations at key points of interaction, which were carefully designed to distinguish our GTPγS- and GDP-bound dimer models and previously reported crystal contacts. To investigate the R135-E168 interaction in the KRAS-GTPγS dimer, we made R135E and E168R mutants, as well as a double charge reversal (R135E/E168R) in both MC-KRAS and FP-KRAS, and performed PRE experiments using FP-KRAS bearing a TEMPO tag on Cys118 to observe intermolecular PRE effects (Figure 5C and S17A). As predicted by the model, experiments with the mutant MC-KRAS-GTPγS-R135E and FP-KRAS-GTPγS-R135E exhibited much less PRE in the α4-α5 interface than those with two wild-type KRAS proteins. We observed similar results with MC-KRAS-GTPγS-E168R and FP-KRAS-GTPγS-E168R. These data indicate that the single mutations in a symmetric manner can disrupt the KRAS-GTPγS dimerization. Furthermore, the introduction of the double charge-reversal mutation R135E/E168R into both MC- and FP-KRAS-GTPγS, which was predicted to rescue the interaction, indeed restored the intermolecular PREs, highlighting the importance of the R135-E168 electrostatic interaction for KRAS-GTPγS dimerization. We also carried out analogous mutational experiments with the GDP-bound form of the KRAS R135E, E168R, and R135E/E168R mutants. Mutation of these residues, which are not involved in dimerization in our model of a KRAS-GDP dimer, had no substantial effects on intermolecular PRE between MC-KRAS-GDP and FP-KRAS-GDP (Figure 5C and S17B). These observations confirmed the specificity of the interaction between R135 and E168 in our KRAS-GTP dimer interface.

Figure 5.

Intermolecular interactions at the α4-α5 dimer interface of the KRAS homodimer in the GTPγS-bound (A) and GDP-bound (B) states, with key side chains shown. (C) Validation of an electrostatic interaction between R135 and E168 within the dimer interface of KRAS-GTPγS using charge-reversal mutations. The mutants R135E, E168R, and the double R135E/E168R mutant were prepared, and intermolecular PRE effects for key probes (V45γ and I142δ of KRAS-GTPγS as well as I133δ and I142δ of KRAS-GDP), induced by Cys118 TEMPO-labeled FP-KRAS (same mutant and nucleotide-bound state), were monitored as indicators of dimerization.

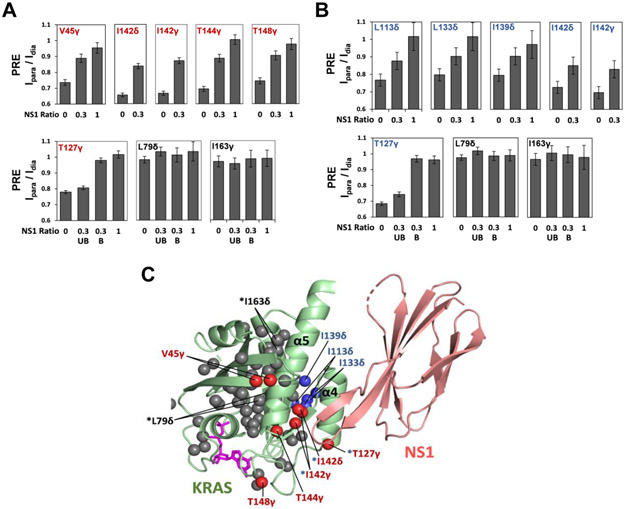

NS1 Monobody Interferes with Dimer-specific PRE for both GTP-loaded and GDP-loaded KRAS.

We previously reported that a synthetic monobody called NS1, which binds to KRAS and HRAS α4-α5, disrupted formation of ‘nanoclusters’ and inhibited RAF dimerization as well as MAPK signaling[3b]. To investigate the impact of NS1 on KRAS dimerization, we examined how NS1 affects intermolecular PRE between Cys118-TEMPO-tagged FP-KRAS and 13C ILVT-labeled FP-FRAS in both the GTPγS- and GDP-bound states on nanodiscs. Addition of NS1 strongly reduced the PRE on several 13C-methyl peaks on the α4-α5 interfaces in both the GTPγS-and GDP-bound state (Figure 6 and S18), supporting our model that NS1 disrupts KRAS dimerization. With a non-saturating molar ratio of NS1 to KRAS (1:0.3), we observed split peaks for L79δ, T127γ, and I163γ, indicating the presence of NS1-bound and free states of KRAS, in slow exchange on the NMR time scale. T127γ is at the α4-α5 dimer interface in both the GTPγS- and GDP-bound dimeric states, and as expected, the peak derived from the NS1-free state exhibits strong PRE, while the NS1-bound peak shows negligible PRE. L79δ and I163γ, which are remote from the Cys118-TEMPO spin label in both the GTPγS- and GDP-bound dimer models, exhibit almost no PRE effects in either state (NS1-bound or free). These effects of NS1 on intermolecular PRE patterns further support our model of KRAS dimerization through the α4-α5 region in both nucleotide states.

Figure 6.

Binding of the monobody NS1 to the α4-α5 interface of KRAS disrupts dimerization. Reductions of intermolecular PRE effects between FP-KRAS molecules in the GTPγS-bound (A) and GDP-bound (B) states induced by titration of NS1. The Ipara/Idia values for several ILVT probes in the α4-α5 region are plotted against the KRAS:NS1 molar ratios (1:0, 1:0.3, and 1:1). “UB” and “B” represent split peaks that correspond to the NS1-unbound and bound forms of FP-KRAS, respectively. (C) Mapping of the probes that exhibit reduced PRE effects upon NS1 addition onto the structure of the KRAS-NS1 complex. These probes, in the GTPγS- and GDP-bound states, are colored in red and blue, respectively, and the superscript “*” represents the probes common to both nucleotide states. ILVT probes that do not exhibit substantial PRE changes upon NS1 addition are colored in dark gray (see Figure S18). The structure of the KRAS (residues 1-172) in complex with NS1 was modeled using the crystal structure of the HRAS-NS1 complex (PDB ID: 5E95).

Discussion

KRAS dimerization requires membrane association, raising the question of what is the critical role of the membrane in promotion of dimerization. While reduced dimensionality on the membrane surface would favour interaction, the lack of ‘cross-dimerization’ between KRAS-GDP and -GTP strongly suggests that specific interactions promote KRAS homo-dimerization. Membrane association may induce dimerization-competent membrane orientations of KRAS, thereby increasing the probability that molecules will meet in productive orientations. Effects of the membrane on protein-protein interactions have been demonstrated by studies of nanodisc-anchored redox proteins that adopt specific conformations to facilitate electron transfer[16].

The main difference between the PRE-driven structures of membrane-anchored KRAS dimers in the active GTPγS-bound and inactive GDP-bound states is the relative orientation of the protomers within the α4-α5 dimer interface, however, the mechanism is not clear since the α4-α5 interface does not undergo substantial conformational changes upon GDP/GTP cycling. A recent MD study suggested that the intramolecular electrostatic interaction between D154 and R161 within the KRAS monomer is less stable in the GTP- than GDP-loaded state, which may facilitate KRAS-GTP dimerization to stabilize this ion-pair[17]. Indeed, our KRAS-GTPγS dimer interface features an intramolecular interaction between D154 and R161, with both residues forming intermolecular hydrogen bonds with Q131 of the opposing protomer. Additionally, the KRAS-GDP dimerization involves an interaction between K172 and E49, a residue located in the ‘switch III’ region that has been proposed to dictate the membrane orientation through rearrangement of its intramolecular bond network upon binding GTP[18]. Therefore, it is possible that the structural rearrangement of E49 in KRAS-GTPγS abrogates its ability to interact with K172, resulting in the formation of a different dimer interface.

Many crystal structures of GTP analogue-bound RAS exhibit contacts between two RAS GTPase-domain monomers within the asymmetric unit. We compared our dimer models of full-length KRAS on the membrane to the assembly observed in the crystal structures of truncated RAS GTPase-domains, most of which are almost identical, regardless of nucleotide state or RAS isoform (HRAS or KRAS). While all involve the α4-α5 interface, the most obvious difference in our model is the relative orientation of the protomers (Figure S19). The angle between the axes of the two α5 helices is ~ 55° in the crystallographic ‘dimers’ versus ~ 20° and ~ 80° in our dimer models of the GTPγS- and GDP-bound forms, respectively. Consistently, our PRE-derived distance restraints cannot be satisfied by the crystallographic dimers (Table S5 and S6). This discrepancy might be attributed to the C-terminal truncation (usually between 166 and 169) of RAS used for crystallography and/or the absence of membrane association. In contrast, crystal structures of full-length (unprocessed) KRAS lack the ‘dimeric’ crystal contacts described above, raising questions about the relevance of the ‘dimer’ interface observed in crystal structures of the truncated form. Specifically, the absence of K172 in the truncated RAS proteins, and the truncation or distorted orientation of E168 at the new C-terminus would disrupt the R135-E168 and E49-K172 interactions that respectively stabilize the GTPγS- and GDP-bound full length KRAS dimer interfaces defined in this study. In support of this model, E168 in our full-length dimer would make a steric clash in the crystallographic dimer orientation (Figure S19A). Notably, E168 and K172 in the HVR are not conserved in HRAS or NRAS, suggesting that full-length RAS dimer interactions may be isoform-specific.

Several reports have observed that the presence of a wild-type KRAS allele can suppress the oncogenicity of a mutant allele[19]. Recently, it was proposed that the mechanism underlying this phenomenon involves formation of signaling-incompetent heterodimers comprising an inactive wild-type KRAS-GDP and an active mutant KRAS-GTP[3c]. Mutations predicted to disrupt dimerization on the basis of crystal contacts (i.e., D154Q and R161E) both impaired the oncogenicity of mutant KRAS and reversed the ability of WT KRAS to suppress mutant KRAS, presumably by interfering with dimerization. While the specific pairing of residues in our model differs from that seen in the crystal contacts, our model still predicts that these mutations would disrupt the KRAS-GTP dimer. However, to our surprise, our data clearly show that cross-dimerization between GDP- and GTP-bound KRAS molecules is unfavourable, raising questions about how wild-type KRAS-GDP might suppress dimerization of GTP-loaded oncogenic mutants. Importantly, our data could provide structural insights into complexes of KRAS dimers with its upstream regulators (e.g., GEF and GAP) and downstream effectors (e.g., RAF kinases) on the membrane surface (see Supporting Information, Section 3).

Conclusion

NMR is a uniquely powerful technique to dissect the structural basis of the dynamic assembly of signaling proteins on the biological membrane. A nanodisc-based system engineered to control KRAS dimerization enabled robust PRE-based structure determination of the transient KRAS dimer on the membrane. The active GTPγS- and inactive GDP-bound KRAS dimers share the α4-α5 interface but are distinct in the relative orientations of the protomers and interacting residue pairs. KRAS-GTP dimerization occurs concomitantly with the exposure of the effector binding sites relative to the membrane, which could facilitate the downstream effector activation. The present data could provide the structural foundation for the development of compounds that interfere with KRAS dimerization on the membrane for anticancer drug discovery. Further, our methodological PRE approaches using a nanodisc-based system should be generally applicable to studies of other GTPases, as well as the effects of oncogenic mutations and/or post-translational modifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (Grant # 703209 and 706696), Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation (Grant # 410008598). and U.S. National Institutes of Health (Grant # R01 CA212608 (S.K.)). M.I. holds a Canada Research Chair in Cancer Structural Biology. NMR spectrometers were funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the NMR Core Facility is supported by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. We thank Dr. Geneviève Seabrook for technical expertise and access to the NMR Core Facility. We thank Dominic Esposito, National Cancer Institute (NCI) RAS Initiative, for providing the baculovirus expression system for fully processed KRAS.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1] a).Cox AD, Der CJ, Small GTPases 2010, 1, 2–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lu S, Jang H, Muratcioglu S, Gursoy A, Keskin O, Nussinov R, Zhang J, Chem Rev 2016, 116, 6607–6665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F, Cell 2017, 170, 17–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]a).Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C, Cancer Res 2012, 72, 2457–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McCormick F, Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 1797–1801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Eser S, Schnieke A, Schneider G, Saur D, Br J Cancer 2014, 111, 817–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Krens LL, Baas JM, Gelderblom H, Guchelaar HJ, Drug Discov Today 2010, 15, 502–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) McCormick F, Expert Opin Ther Targets 2015, 19, 451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]a).Nan X, Tamguney TM, Collisson EA, Lin LJ, Pitt C, Galeas J, Lewis S, Gray JW, McCormick F, Chu S, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 7996–8001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Spencer-Smith R, Koide A, Zhou Y, Eguchi RR, Sha F, Gajwani P, Santana D, Gupta A, Jacobs M, Herrero-Garcia E, Cobbert J, Lavoie H, Smith M, Rajakulendran T, Dowdell E, Okur MN, Dementieva I, Sicheri F, Therrien M, Hancock JF, Ikura M, Koide S, O’Bryan JP, Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13, 62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ambrogio C, Kohler J, Zhou ZW, Wang H, Paranal R, Li J, Capelletti M, Caffarra C, Li S, Lv Q, Gondi S, Hunter JC, Lu J, Chiarle R, Santamaria D, Westover KD, Janne PA, Cell 2018, 172, 857–868 e815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chen M, Peters A, Huang T, Nan X, Mini Rev Med Chem 2016, 16, 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]a).Spencer-Smith R, O’Bryan JP, Semin Cancer Biol 2019, 54, 138–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Holderfield M, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 828–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F, Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 272–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]a).Jang H, Muratcioglu S, Gursoy A, Keskin O, Nussinov R, Biochem J 2016, 473, 1719–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Muratcioglu S, Chavan TS, Freed BC, Jang H, Khavrutskii L, Freed RN, Dyba MA, Stefanisko K, Tarasov SG, Gursoy A, Keskin O, Tarasova NI, Gaponenko V, Nussinov R, Structure 2015, 23, 1325–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Guldenhaupt J, Rudack T, Bachler P, Mann D, Triola G, Waldmann H, Kotting C, Gerwert K, Biophys J 2012, 103, 1585–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sayyed-Ahmad A, Cho KJ, Hancock JF, Gorfe AA, J Phys Chem B 2016, 120, 8547–8556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Prakash P, Sayyed-Ahmad A, Cho KJ, Dolino DM, Chen W, Li H, Grant BJ, Hancock JF, Gorfe AA, Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhou Y, Prakash P, Liang H, Cho KJ, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF, Cell 2017, 168, 239–251 e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Clore GM, Biochem Soc Trans 2013, 41, 1343–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]a).Hagn F, Nasr ML, Wagner G, Nat Protoc 2018, 13, 79–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McLean MA, Gregory MC, Sligar SG, Annu Rev Biophys 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ravula T, Hardin NZ, Ramamoorthy A, Chem Phys Lipids 2019, 219, 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gillette WK, Esposito D, Abreu Blanco M, Alexander P, Bindu L, Bittner C, Chertov O, Frank PH, Grose C, Jones JE, Meng Z, Perkins S, Van Q, Ghirlando R, Fivash M, Nissley DV, McCormick F, Holderfield M, Stephen AG, Sci Rep 2015, 5, 15916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mazhab-Jafari MT, Marshall CB, Smith MJ, Gasmi-Seabrook GM, Stathopulos PB, Inagaki F, Kay LE, Neel BG, Ikura M, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 6625–6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alhaique F, Bertini I, Fragai M, Carafa M, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Inorganica Chimica Acta 2002, 331, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yu D, Volkov AN, Tang C, J Am Chem Soc 2009, 131, 17291–17297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]a).Kooshapur H, Schwieters CD, Tjandra N, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2018, 57, 13519–13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Madl T, Guttler T, Gorlich D, Sattler M, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2011, 50, 3993–3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van Zundert GCP, Rodrigues J, Trellet M, Schmitz C, Kastritis PL, Karaca E, Melquiond ASJ, van Dijk M, de Vries SJ, Bonvin A, J Mol Biol 2016, 428, 720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]a).Mahajan M, Ravula T, Prade E, Anantharamaiah GM, Ramamoorthy A, Chem Commun (Camb) 2019, 55, 5777–5780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Prade E, Mahajan M, Im SC, Zhang M, Gentry KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2018, 57, 8458–8462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ravula T, Barnaba C, Mahajan M, Anantharamaiah GM, Im SC, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A, Chem Commun (Camb) 2017, 53, 12798–12801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pantsar T, Rissanen S, Dauch D, Laitinen T, Vattulainen I, Poso A, PLoS Comput Biol 2018, 14, e1006458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]a).Abankwa D, Hanzal-Bayer M, Ariotti N, Plowman SJ, Gorfe AA, Parton RG, McCammon JA, Hancock JF, EMBO J 2008, 27, 727–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Solman M, Ligabue A, Blazevits O, Jaiswal A, Zhou Y, Liang H, Lectez B, Kopra K, Guzman C, Harma H, Hancock JF, Aittokallio T, Abankwa D, Elife 2015, 4, e08905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]a).Burgess MR, Hwang E, Mroue R, Bielski CM, Wandler AM, Huang BJ, Firestone AJ, Young A, Lacap JA, Crocker L, Asthana S, Davis EM, Xu J, Akagi K, Le Beau MM, Li Q, Haley B, Stokoe D, Sampath D, Taylor BS, Evangelista M, Shannon K, Cell 2017, 168, 817–829 e815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Westcott PM, Halliwill KD, To MD, Rashid M, Rust AG, Keane TM, Delrosario R, Jen KY, Gurley KE, Kemp CJ, Fredlund E, Quigley DA, Adams DJ, Balmain A, Nature 2015, 517, 489–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.