Obesity is a serious chronic disease and worldwide public health problem. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 650 million adults in the world were obese and three times more individuals were overweight in 2016. Obesity is associated with type II diabetes, hepatic steatosis, cardiovascular diseases, systemic chronic inflammation, and at least 13 types of cancer. Unfortunately, few effective remedies are available for obesity. The major problem is that most patients suffer from weight regain 2–3 years after obesity treatments, such as obesity drugs, lifestyle interventions (including exercise, diet restrictions, and diet modification), and bariatric surgery. Along with weight regain, most of the initial beneficial changes in metabolomic and transcriptomic profiles dissipate, including insulin sensitivity, the level of adipokines and blood cholesterol. This phenomenon has been defined as “obesogenic memory”.1,2 Obesogenic memory causes repeated weight loss and gain along with obesity therapy, which is called “weight cycling”, leading to a worse healthy status than would result from simple obesity.3,4

Interestingly, weight regain occurred in individuals who strictly followed lifestyle intervention strategies. There was a follow-up metabolic analysis of 14 champions from The Biggest Loser, a famous TV show about a weight loss competition.5 These individuals had lost ~60 kg of body mass during the competition. However, after 6 years, most of them regained body weight even if they maintained food restriction and excise. It is still unclear where obesogenic memory is stored, as there are thousands of reports indicating that body weight changes may be influenced by various tissues/organs, including the central nervous system (CNS), immune system, muscles, adipose tissue, intestine, liver, and bone. Defining the crucial tissue for obesogenic memory will help us to identify more effective strategies for overcoming obesity.

Existing clinical data suggest that weight regain is closely related to immune responses in humans. A recent study showed that weight cycling impaired glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity by increasing IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels.3 The possibility of weight regain could be predicted by inflammatory markers and insulin in blood before dietary intervention in obese children.6 Furthermore, the dietary inflammatory index, which shows the effects of intake of specific nutrients on inflammatory parameter changes in the blood, was positively correlated with weight regain.7 All these data suggest that immune cells play an important role in obesogenic memory.

To dissect the mechanisms of obesogenic memory, rodent models have been used. A weight cycling rodent model was established by repeated alternative feeding with a high-fat diet and a normal diet. Recently, there have been many reports suggesting that obesogenic memory is closely associated with immune cells in rodent models. Since various tissues/organs are involved in obesogenic memory, the tissue/organ-specific inflammation patterns are different from each other.

The most important tissue related to obesogenic memory is adipose tissues. ECM remodeling, adipokine secretion, lipolysis, adipogenic potential, and lipid storage capacity in adipose tissue are all related to weight regain. In obese white adipose tissue (WAT), type I immune cells, such as M1 macrophages, Th1 cells, B cells, NK cells, and mast cells, increase.8 In contrast, the numbers of type II immune cells, such as M2 macrophages, Th2 cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs), decrease.8 Global transcriptome analysis identified that weight regain activated adaptive immune responses in mouse white adipose tissue.9 Our recent data confirmed that CD4+ effector T lymphocytes, including Th1 and Th17 cells, were significantly increased in the epididymal adipose tissue of mice with a history of obesity.2 Chronic inflammation and immune cell infiltration in adipose tissue were associated with the secretion of adipokines.10,11 CD4+ and CD8+ memory effector T lymphocytes accumulated in adipose tissues and impaired insulin sensitivity in weight cycling models.4 These observations suggest that inflammation is increased in obese WAT and affects the function of WAT. Based on these reports, the immune cells in adipose tissue, especially adaptive immune cells, should be considered one of the origins of weight regain.

Inflammation in tissues/organs other than adipose tissue is also important in weight regain. The CNS is the direct controller of appetite and the resting metabolic rate (RMR). Neuronal inflammation in the CNS, especially hypothalamic inflammation, is associated with weight regain. Skeletal muscle is the largest metabolic organ in animals. Skeletal muscle inflammation is associated with insulin resistance and obesity, but there are few studies about its role in obesogenic memory.

The liver is one of the most important metabolic organs in humans and animals. It is well known that inflammation in the liver is associated with obesity, but the role of liver inflammation in obesogenic memory remains unclear. A report suggested that obesogenic memory is associated with long-term increases in adipose tissue inflammation in mice and obese patients but not liver inflammation.1 However, a recent study showed the opposite: during weight cycling, liver inflammation was important for insulin sensitivity, which is an inconsistent index of weight regain.12 However, the data about liver inflammation in obesogenic memory are descriptive and need further study.

In addition to tissues/organs, the microbiota also contributes to weight regain. The changes in the gut microbiota caused by obesity alter the metabolites provided to the host, such as short chain acids and indoles, which act as signals and mediate the related behavior of the host. The intestinal microbiome signature persisted in mice with a history of obesity and promoted faster weight regain, which was also related to diminished postdieting flavonoid levels and reduced energy expenditure.13 Perturbation of the intestinal microbiota and changes in intestinal permeability may be potential triggers of inflammation in obesity. Immune cells also regulate the composition of the microbiota in obesity. Th17 cells in the gut are one of the key players that sense and reshape the microbiota.14

Compared to innate immune cells, adaptive immune cells may play a more essential role in the process of weight regain based on published data. Our group recently reported that CD4+ T cells were capable of remembering an obese state based on a weight regain mouse model.2 CD4+ T cells are sufficient and necessary for weight regain and are a direct carrier of obesogenic memory. When CD4+ T cells from mice with a history of obesity are transplanted into normal mice, the normal mice gain obese memory. The rate of weight gain is significantly higher in these transplanted mice than in the control mice and is similar to that in donor mice with a history of obesity. Although our research demonstrated that CD4+ T cells were critical for obesogenic memory, we did not identify which subpopulation of CD4+ T cells is essential. CD4+ T cells can be divided into several subpopulations according to their functions, such as memory T cells and effector T cells or T helper cells and regulatory T cells. T helper cells can be further divided into Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, and Th22 cells. The next question is how to identify the subpopulation of CD4+ T cells crucial for obesogenic memory.

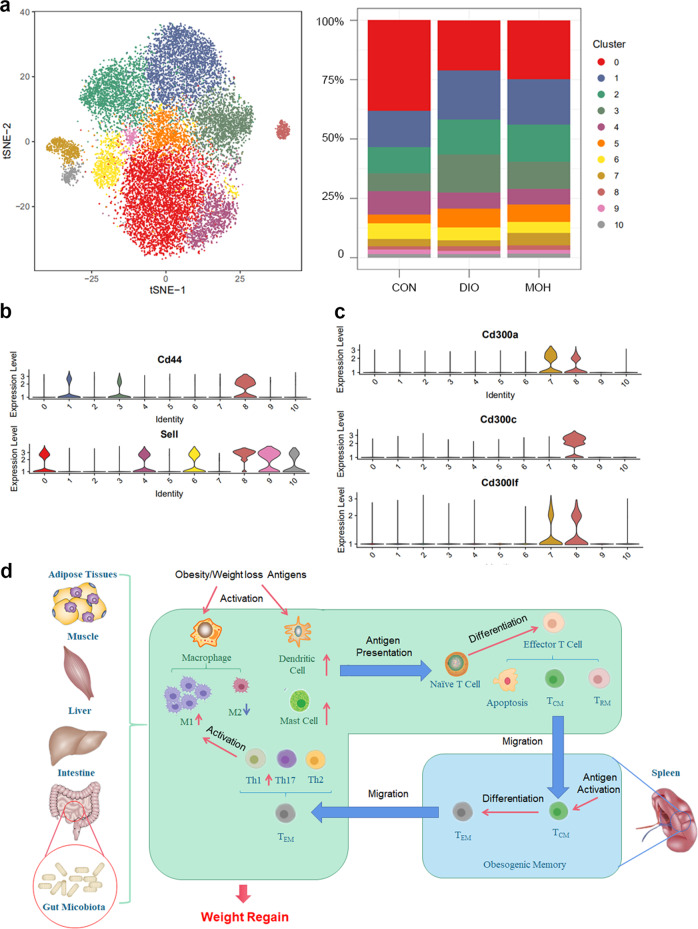

In the processes of the adaptive immune response related to T cells, the first step is the presentation of antigens by APCs. In the following step, naïve T cells are activated by antigens and differentiate into effector T cells. When the stimulation signals disappear, most effector T cells die, and the remaining T cells become memory T cells. The memory T cells will stay in the local tissue (resident memory T cells) or migrate to lymph nodes or spleen (central memory T cells). When the stimulation signals resume, memory T cells will be reactivated, rapidly proliferate and differentiate into effector memory T cells. In our previous study, transplanted CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen. This suggests that these cells may be central memory T cells. Recently, we isolated CD4+ splenocytes and performed single-cell sequencing. The results showed that some subpopulation changes in the CD127− cluster were correlated with weight regain (Fig. 1a). Cluster 8 cells enriched in obese mice and normal-weight mice with a history of obesity history were positive for markers of central memory T cells (CD44+CD62L+), supporting our hypothesis (Fig. 1b). However, these results should be confirmed by FACS using more markers, since the other subpopulations cannot be excluded from memory T cells according to only RNA sequencing data. Furthermore, there are further subpopulations in Cluster 8 according to the diverse gene expression levels of CD62L.

Fig. 1.

T cells can remember the obese state. a Left panel, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis of 20,914 single cells sampled from mouse CD4+CD127− splenocytes. Eleven main cell type clusters are labeled in the t-SNE map. Right panel, the composition of splenocytes from different groups. b Expression of CD44 and Sell (CD62L) in different clusters. c Expression of CD300a, CD300c, and CD300lf in different clusters. d Schematic representation of the T cell-associated obesogenic memory theory. CON control group, DIO diet-induced obesity group, MOH obese history group, TRM resident memory T cells, TCM central memory T cells, TEM effector memory T cells

If the CD4+ T cells essential for obesogenic memory are central memory T cells, where and how are they activated? These activating signals should increase during obesity or the process of weight loss and again during the weight regain process. Signals that meet these two conditions might include a specific lipid during high-fat diet consumption, some metabolites secreted by the intestinal flora in obese individuals, and the cellular contents released from dead cells due to the stress of weight loss. One solution to identify the responsible signals could be a large-scale screen for metabolites in different tissues and FACS for subpopulations of T cells with specific receptors for the changed metabolites. In skeletal muscles, many lipids are alerted in weight regain. We noticed that phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) species accumulated in skeletal muscles after weight regain.15 Interestingly, several members of the CD300 family, the receptors of PE, were highly expressed in the subpopulation, which we identified as central memory T cells by single-cell sequencing (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the metabolites of other tissues/organs, such as adipose tissue and the liver, should be analyzed to confirm an association with obesity. Detailed identification of immune cells recruited to different tissues/organs in obesity and during weight regain will provide more information.

How do T cells mediate weight regain? According to a recent report, we know that T cells can affect the function of adipose tissue, the microbiota, the liver and skeletal muscle.10–12,14,15 The cytokine and chemokine secretion, immune cell regulation, effects on resident tissue ECM components, lipolysis, and lipid uptake are all possible regulated processes. Weight regain is a complex physical phenomenon associated with various tissues/organs. The identified involved T cells provide a clue for dissecting the complex mechanisms of obesogenic memory.

In summary, recently published data and our work suggest that immune cells, especially T cells, play an essential role in obesogenic memory (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, our single-cell sequencing data indicate that the memory carrier may be a subpopulation of central memory T cells expressing receptors for PE species. However, further study is needed to uncover the underlying mechanisms of immune cell-related obesogenic memory.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant 2018YFA0801100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31772550).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Minli Sun, Shang Zheng

These authors jointly supervised this work: Xiang Gao, Zhaoyu Lin

Contributor Information

Xiang Gao, Email: Gaoxiang@nju.edu.cn.

Zhaoyu Lin, Email: Linzy@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Schmitz J, et al. Obesogenic memory can confer long-term increases in adipose tissue but not liver inflammation and insulin resistance after weight loss. Mol. Metab. 2016;5:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou J, et al. CD4+ T cells memorize obesity and promote weight regain. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018;15:630–639. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Jiang L, Yang M, Wu YW, Sun JZ. Impact of weight cycling on CTRP3 expression, adipose tissue inflammation and insulin sensitivity in C57BL/6J mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;16:2052–2059. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson EK, Gutierrez DA, Kennedy A, Hasty AH. Weight cycling increases T-cell accumulation in adipose tissue and impairs systemic glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2013;62:3180–3188. doi: 10.2337/db12-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fothergill E, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity. 2016;24:1612–1619. doi: 10.1002/oby.21538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong LC, et al. Insulin resistance and inflammation predict kinetic body weight changes in response to dietary weight loss and maintenance in overweight and obese subjects by using a Bayesian network approach. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;98:1385–1394. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhammad, H. F. L. et al. Dietary intake after weight loss and the risk of weight regain: macronutrient composition and inflammatory properties of the diet. Nutrients10.3390/nu9111205 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Chatzigeorgiou A, Karalis KP, Bornstein SR, Chavakis T. Lymphocytes in obesity-related adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2583–2592. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyung DS, et al. Global transcriptome analysis identifies weight regain-induced activation of adaptive immune responses in white adipose tissue of mice. Int. J. Obes. 2018;42:755–764. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbosa-da-Silva S, Fraulob-Aquino JC, Lopes JR, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Aguila MB. Weight cycling enhances adipose tissue inflammatory responses in male mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wainright KS, et al. Retention of sedentary obese visceral white adipose tissue phenotype with intermittent physical activity despite reduced adiposity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015;309:R594–R602. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00042.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Y, et al. Lmo4-resistin signaling contributes to adipose tissue-liver crosstalk upon weight cycling. FASEB J. 2020;34:4732–4748. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902708R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thaiss CA, et al. Persistent microbiome alterations modulate the rate of post-dieting weight regain. Nature. 2016;540:544–551. doi: 10.1038/nature20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong CP, et al. Gut-specific delivery of T-helper 17 cells reduces obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1998–2010. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eum JY, et al. Lipid alterations in the skeletal muscle tissues of mice after weight regain by feeding a high-fat diet using nanoflow ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2020;1141:122022. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2020.122022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]