Abstract

Public health interventions to control the recent emergence of plasmid-mediated tigecycline resistance genes rely on a comprehensive understanding of its epidemiology and distribution over a wide range of geographical scales. Here we analysed an Escherichia coli collection isolated from pigs and chickens in China in 2018, and ascertained that the tet(X4) gene was not present at high prevalence across China, but was highly endemic in northwestern China. Genomic analysis of tet(X4)-positive E. coli demonstrated a recent and regional dissemination of tet(X4) among various clonal backgrounds and plasmids in northwestern China, whereas a parallel epidemic coincided with the independent acquisition of tet(X4) in E. coli from the remaining provinces. The high genetic similarity of tet(X4)-positive E. coli and human commensal E. coli suggests the possibility of its spreading into humans. Our study provides a systematic analysis of the current epidemiology of tet(X4) and identifies priorities for optimising timely intervention strategies.

Subject terms: Antimicrobial resistance, Bacterial genes

Sun et al. analyse E. coli strains from pigs and chickens in Chinese farms and slaughterhouses, and reveal that while the tet(X4) gene is not ubiquitous across China, it is highly endemic in northwestern China. Genomic analysis of these strains shows recent and independent acquisitions of plasmids in across regions.

Introduction

The incessant emergence of novel and transmissible antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mechanisms has frustrated clinicians because limited antimicrobial agents are left for the treatment of infectious diseases1. Classified by the World Health Organization as a critically important antimicrobial agent, tigecycline provides a key line of defense against multi-drug-resistant bacteria, particularly in cases of life-threatening infections2. Up until 2019, reported resistance to tigecycline was commonly mediated by mutational and regulatory changes with limited lateral transferability3,4. However, plasmid-encoded tet(X) genes that confer high-level tigecycline resistance were first described in isolates from animals and humans in China in around 20185–7. Subsequently, several more tet(X) variants—tet(X3), tet(X4), and tet(X5)—were identified on transferable plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter isolates from animals and humans in China5,6. In addition to their ability to degrade all tetracyclines, the novel plasmid-mediated tet(X) variants show a much more efficient horizontal transferability, making the host bacteria and recipient pathogens a new and severe threat to global public health5–7.

Initial epidemiological studies in China indicated that the current presence of tet(X3) and tet(X4) is still rare in the human sector, but more common in food animals, meat products, and the surrounding niches5–8, suggesting that the food animals may be large reservoir of these novel mobile tigecycline resistance genes. A further retrospective study reported that the emergence of tet(X4) in food animals is a recent event9, but is now spreading geographically5–8,10, indicating an emerging risk of food animals as reservoirs in spreading these genes. Public health interventions to control the spread of AMR genes rely on a comprehensive understanding of its current epidemiology and distribution over a wide range of geographical scales. However, tigecycline is not authorized in food animals, its resistance in animals is not routinely monitored and largely unknown. Given the clinical importance of tigecycline and the emerging risk of food animals in spreading its resistance, a further comprehensive surveillance is urgently recommended to underline the current situation of these newly identified tet(X) variants5–10.

Here, we analysed an E. coli collection isolated from pigs and chickens in China 2018. We ascertained that the gene tet(X4) was not present in high prevalence on a China-wide scale, but was highly endemic in northwestern China. We illustrated a complex combination of multiple genetic vehicles (mobile genetic elements, plasmids and bacterial lineages) in the spreading of the tet(X4) gene, and showed a possibility of tet(X4)-positive E. coli in spreading into the humans.

Results

tet(X4) was endemic in northwestern China

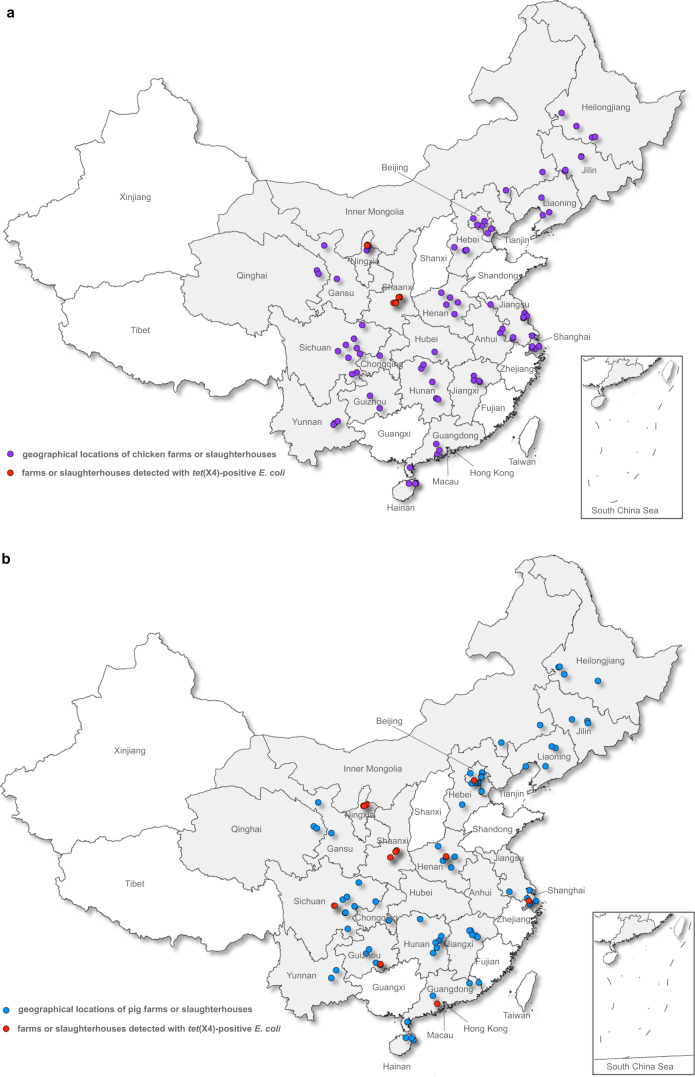

From the 2475 E. coli isolates included in the study, 125 tigecycline-non-susceptible E. coli were recovered. The tet(X4) gene was detected in 95 isolates originating from eight provinces, including 60 pig isolates (60/1,230, 4.9%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.7–6.2%) and 35 chicken isolates (35/1,245, 2.8%, 95% CI: 2.0–3.9%) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Shaanxi and Ningxia, two neighbouring provinces in northwestern China, had a relatively high tet(X4) prevalence in both pigs (30/60, 50.0%, Shaanxi; 20/45, 44.4%, Ningxia) and chickens (20/45, 44.4%, Shaanxi; 15/45, 33.3%, Ningxia). In contrast, the tet(X4) gene appeared sporadically among pig isolates from Sichuan (4/150, 2.7%), Henan (2/75, 2.7%), Guizhou (1/60, 1.7%), Beijing (1/135, 0.74%), Shanghai (1/75, 1.3%), and Guangdong (1/75, 1.3%) and was negative in the remaining 14 provinces. The chicken isolates that were positive for tet(X4) were only detected from Shaanxi and Ningxia (Table 1 and Fig. 1). All amplified fragments had 100% sequence homology to the original tet(X4) gene5. The tet(X3) and tet(X5) genes were absent in the current strain collection. The underlying tigecycline resistance mechanisms of the 30 tigecycline-non-susceptible E. coli that were all negative for novel tet(X) variants were not explored in the current study and will be discussed elsewhere.

Table 1.

Distribution of E. coli and tet(X4)-positive E. coli from pigs and chickens in China in 2018.

| Province | No. of E. coli isolates | No. of positive E. coli | % of positive E. coli (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | Pig | Chicken | |

| Beijing | 135 (9)a | 60 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.74% | 0.00% |

| Chongqing | 30 (2) | 15 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Gansu | 30 (2) | 30 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Guangdong | 75 (5) | 60 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.33% | 0.00% |

| Guizhou | 60 (4) | 30 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.67% | 0.00% |

| Hainan | 45 (3) | 45 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Hebei | 15 (1) | 45 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Heilongjiang | 60 (4) | 60 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Henan | 75 (5) | 75 (5) | 2 (1) | 0 | 2.67% | 0.00% |

| Hunan | 60 (4) | 90 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Inner Mongolia | 30 (2) | 15 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Jiangsu | 15 (1) | 150 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Jiangxi | 75 (5) | 60 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Jilin | 45 (3) | 60 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Liaoning | 75 (5) | 45 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Ningxia | 45 (3) | 45 (3) | 20 (3) | 15 (2) | 44.44% | 33.30% |

| Qinghai | 30 (2) | 30 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Shaanxi | 60 (4) | 45 (3) | 30 (4) | 20 (3) | 50.00% | 44.40% |

| Shanghai | 75 (5) | 75 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.33% | 0.00% |

| Sichuan | 150 (10) | 135 (9) | 4 (1) | 0 | 2.67% | 0.00% |

| Tianjin | 15 (1) | 30 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Yunnan | 30 (2) | 45 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Total | 1230 (82) | 1245 (84) | 60 (13) | 35 (5) | 4.88% (3.74–6.23%) | 2.81% (1.97–3.89%) |

aNumbers in parentheses are numbers of farms and slaughterhouses.

Fig. 1. Geographical distribution of farms and slaughterhouses presenting E. coli isolates in 2018 in China.

aE. coli isolates from chickens (n = 1245). bE. coli isolates from pigs (n = 1230). Provinces and municipalities included in the study are shaded in grey, dots on the maps indicate locations of farms or slaughterhouses in included in the study, red dots indicate the farms or slaughterhouses tested positive for tet(X4).

The antimicrobial resistant phenotype and genotype

Susceptibility testing confirmed that 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli showed resistance to tigecycline (minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) 4–32 mg L−1), doxycycline (32–128 mg L−1), and florfenicol (32–128 mg L−1) but exhibited sensitivity to meropenem. A few of the isolates showed resistance to colistin (n = 3, 3.2%), cefepime (n = 1, 1.1%), ceftriaxone (n = 4, 4.2%), aztreonam (n = 5, 5.3%), and gentamicin (n = 7, 7.4%), while the majority were resistant to ampicillin (n = 92, 96.8%) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 94, 98.8%) (Supplementary Data 1).

Apart from tet(X4), a median of 13 AMR genes (range, 2–20) was detected in the genome of each isolate. Genes coding for resistance to phenicols (floR, 91/95), tetracyclines (tet(A), 87/95), sulfonamides (sul2, 26/39; sul3, 71/95), aminoglycosides (strA, 81/95; strB, 81/95; aadA2, 70/95), and trimethoprims (drfA12, 69/95) were highly present in the E. coli harbouring tet(X4). The colistin resistance gene mcr-1 was detected in two of the 95 E. coli isolates (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2). All tet(X4)-positive E. coli were classified into five phylogroups (A, n = 79; B1, n = 12; B2, n = 1; C, n = 1, and F, n = 2). One pig strain SC-P337 (Sichuan, ST4541, O146:H28) was placed into group B2, which is commonly known as being highly pathogenic, and carried a greater number of virulence-factor-associated genes (n = 62) than isolates from group A (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2).

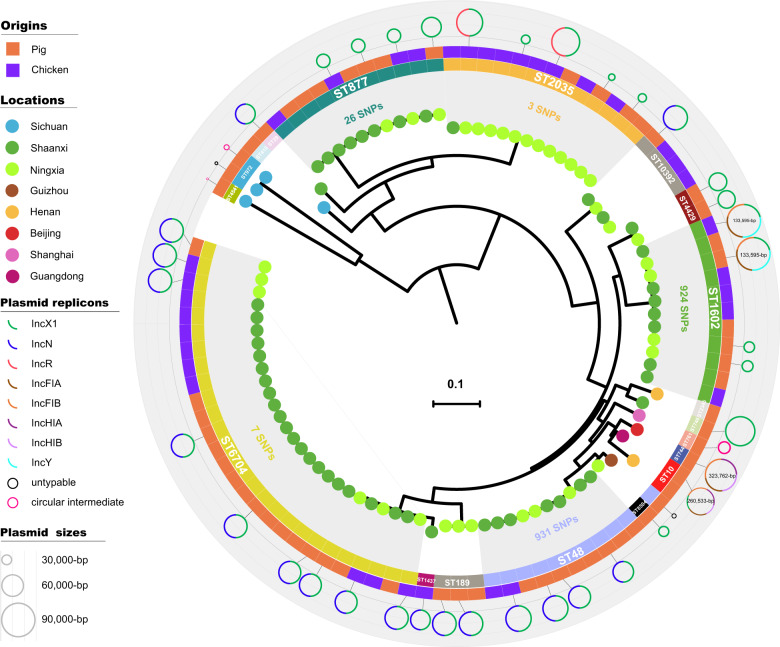

Genomic diversity of tet(X4)-positive E. coli

In silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST) clustered the 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli into 19 distinct sequence types (STs), with 60 pig isolates clustered in 18 STs and 35 chicken isolates in seven STs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although diversified in STs, the majority (76.8%, 73/95) of the isolates were concentrated into five major STs, 6704 (27/95), 2035 (13/95), 48 (11/95), 1602 (11/95), and 877(11/95), which mostly (73/74) originated from Shaanxi and Ningxia (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Isolates within each major ST were characterized by low levels of core genome diversity that was reflected by a relatively limited number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (differing in 3–931 SNPs) (Fig. 2). However, isolates (n = 10) from the remaining six provinces and municipalities showed relatively greater genetic diversity among each other, composing 8 of the 19 STs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree of the 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli analysed in this study.

Neighbour-Joining tree constructed based on 162,383 core-genomic SNPs. Each isolate is labelled on the node with a coloured dot in representing its location, the STs are labelled and shown in the inner ring (the five major lineages are indicated with grey), the origins of the isolates are indicated by coloured squares in the outer ring, and the 42 circles differing in coloured components representing the completely sequenced plasmids and circular intermediates in connecting each isolate. Squares with no connected plasmid circles are isolates not selected for ONT long-read sequencing.

Versatile plasmids harbouring tet(X4)

Based on the phylogenetic analysis, around one-third of the isolates within each of the major lineages were selected (n = 25), together with most of the remaining isolates (n = 17), for Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) long-read sequencing (Supplementary Data 2). Hybrid de novo assembly produced 39 completely sequenced plasmids possessing tet(X4) and three circular intermediates (CIs) harbouring tet(X4) but without replicons. Incompatibility typing of the 39 plasmids (ranging in sizes from 8581 to 322,239 bp) showed a striking variety of plasmid types. In addition to a handful of IncX1 plasmids (n = 13; 21,050–82,762 bp) and two untypable plasmids (8581 and 12,805 bp), a majority of the plasmids (25/39) were detected with multi-replicons, including IncX1-IncN (n = 18; 55,530–71,790 bp), IncX1-IncR (n = 2; 76,546 bp and 77,171 bp), IncX1-IncFIA/B-IncY (n = 2; 133,595 bp and 133,595 bp), IncX1-IncFIA/B-IncHI1A/B (n = 1; 260,533 bp), and IncFIA/B-IncHI1A/B (n = 1; 323,762 bp) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 2). Plasmids of the same Inc type could be identified not only from isolates of the same lineage, but also from isolates of the different lineages, indicating the spread of the tet(X4) gene is combining vertical and horizontal transferability (Fig. 2). Outside northwestern China, plasmids exhibited limited comparability but endemism to those harboured in the major lineages, such as the two large multi-replicon plasmids in the isolates from Beijing (ST744, IncFIA/B-IncHI1A/B) and Guangdong (ST10, IncX-IncFIA/B-IncHI1A/B), as well as the small untypable plasmids from Sichuan (ST792) and Guizhou (ST48); however, the endemic IncX1 and IncX1-IncN plasmids from northwestern China were not observed elsewhere (Fig. 2).

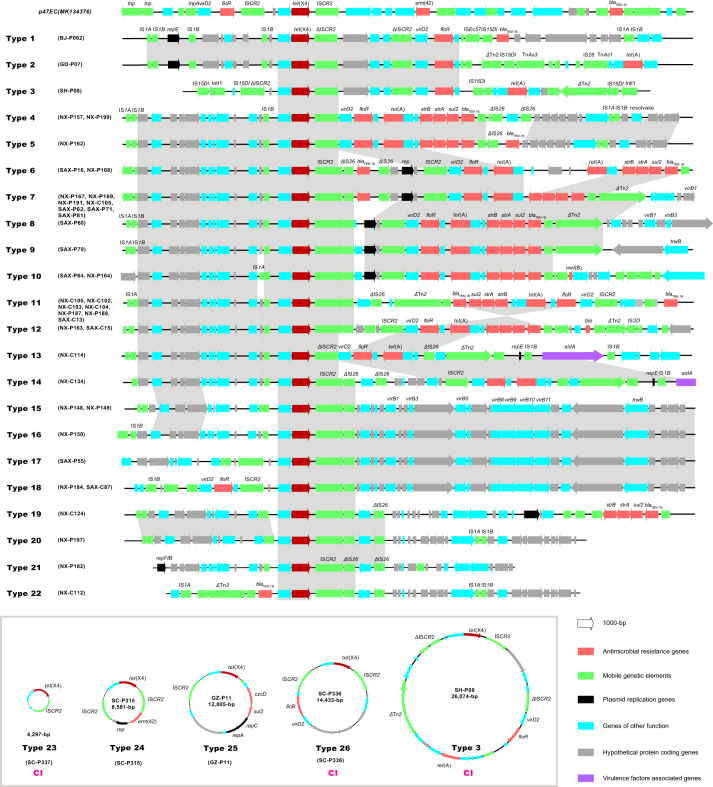

MGE arrangements in spreading tet(X4)

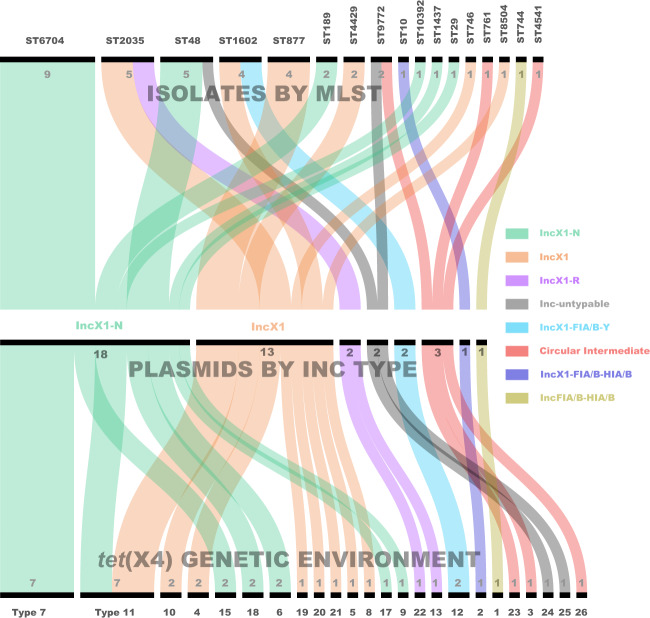

To further analyse the transfer of tet(X4) via mobile genetic elements (MGE), the sequenced plasmids were probed for tet(X4) genetic contexts and were subsequently correlated to plasmid types and the host strains. The genetic environments of tet(X4) were clustered into 26 types, differing mostly in the variable context downstream of tet(X4) but showing a relatively conserved architecture upstream of the gene (Fig. 3). Compared with the flanking stance of the two ISCR2 copies in the original tet(X4)-harbouring plasmid p47EC (ISCR2-ORF2-abh-tet(X4)-ISCR2)5, the upstream copy of ISCR2 adjacent to abh-tet(X4) was absent in most of the present types (20/26) but generally replaced by a truncated IS1B element (IS1B-abh-tet(X4)-ISCR2). In contrast, the downstream copy of ISCR2 remained tightly associated with tet(X4), forming a unified central region abh-tet(X4)-ISCR2 (Fig. 3). A further downstream search generally found a second copy of ISCR2 (12/26, type 1–3, 6–12, 14, and 19), which was joined by the type IV secretion system component virD2 relaxase and led to a set of other resistance determinants, mainly a gene cluster of floR, tet(A), strB, strA, sul2, blaTEM-1B, and occasionally mef(B) and ble. Whenever the second copy of ISCR2 was absent, virD2 and the adherent resistance genes were linked directly to the first copy of ISCR2 downstream of tet(X4) (type 4, 5, 13, 24, and 26) (Fig. 3). By connecting the derived genetic environment types back to plasmids (seven Inc types) and the host strains (16 STs), we illustrated a complex combination of multiple genetic vehicles in the spreading of the tet(X4) gene (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Genetic environment of tet(X4) in the 39 completely sequenced plasmids and 3 circular intermediates.

The arrows indicate the direction of transcription of the genes, and the genes are differentiated by colours. Regions of >99% homology are marked by grey shading.

Fig. 4. Sankey diagram combining the isolates, plasmids, and genetic environments bearing tet(X4).

The lines are drawn connecting STs, plasmid Inc types, and tet(X4) genetic environments based on corresponding information from the 39 completely sequenced plasmids and 3 circular intermediates as well as the host strains. The diameter of the line is proportional to the number of isolates, which is also labelled at the consolidation points. Lines are coloured based on plasmid Inc types.

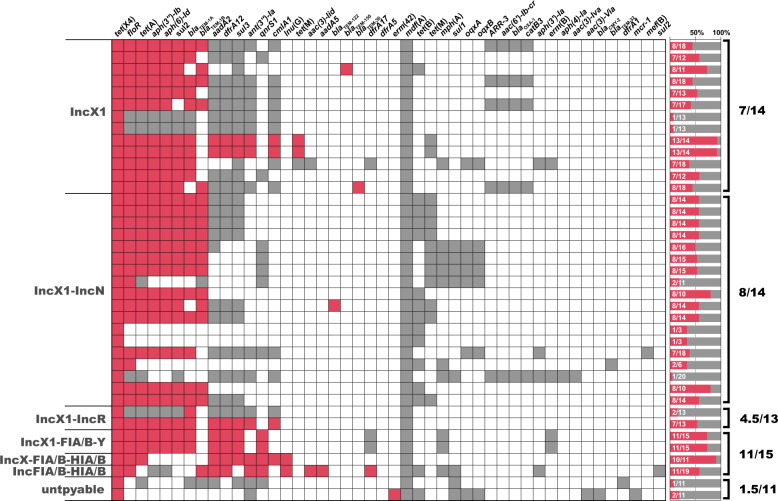

The plasmid resistome in connecting tet(X4)

Given the fact of co-selection in driving plasmids’ persistence, we further examined the resistome of tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids. A median of eight different AMR genes (range, 1–13) was detected within the 39 completely sequenced plasmids, while the median number of AMR genes was 14 (range, 3–20) when scrutinizing the 39 whole genomes. Indeed, we found that a majority of tet(X4)-positive plasmids (23/39) possessed over half of the whole genomes’ resistance genes (Fig. 5), indicating the central role of tet(X4)-positive plasmids in facilitating the host bacteria’s resistance to antimicrobials.

Fig. 5. Heatmap showing the incidence of AMR genes within the 42 completely sequenced tet(X4)-positive E. coli.

Each row in the heat map represents one isolate. Isolates are grouped by incompatibility types of the tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids. Coloured cells in each row indicate the presence of a particular resistance gene (as labelled at the top). Red cells indicate AMR genes located on the tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids; grey cells indicate AMR genes in the genome but not on the tet(X4)-harbouring plasmid. Bars on the left indicate the percentage of AMR genes located on tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids from that of the whole genome. The fractions indicate the median number of AMR genes on tet(X4)-harbouring plasmid/AMR genes within the whole genome.

The phenicol resistance gene floR represented the highest occurrence (31/39), followed by genes conferring resistance to tetracyclines (tet(A), 28/39), aminoglycosides (aph(3”)-Ib, 27/41 and aph(6)-Id, 27/39), sulfonamides (sul2, 26/39), and β-lactams (blaTEM-1A, 25/39 and blaTEM-1B, 18/39). Generally, high numbers of resistance genes were observed in the syncretic plasmids with three or more replicons (median, 11) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 2).

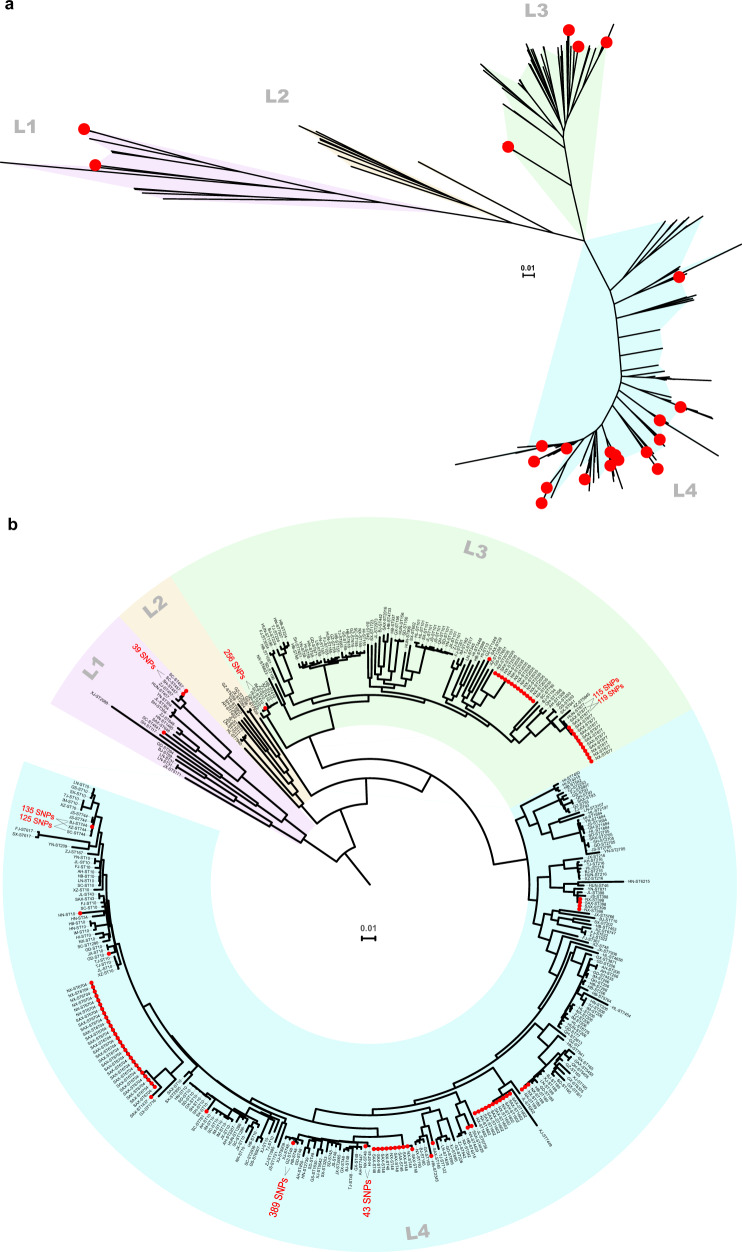

High genetic propensity of tet(X4) in spreading into humans

To determine the genetic propensity of tet(X4)-positive isolates to spread into the human sector, we analysed the genetic relatedness of our 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli to 287 publicly available draft genomes of human commensal E. coli (PRJNA400107) that were negative for tet(X4). The negative isolates were non-duplicates and originated from healthy individuals across China in 2016 as part of a previous study characterising mcr-1 carriage in humans11. The 95 tet(X4)-harbouring E. coli were phylogenetically clustered into three of the four Bayesian lineages generated from the human isolates (L1, n = 3; L3, n = 26, and L4, n = 66) (Fig. 6a). A large proportion of our animal-derived tet(X4)-harbouring E. coli displayed high genetic similarity (25/95, as small as 39 SNPs) to the E. coli of human origin (Fig. 6b) from various provinces (Supplementary Fig. 3). Of particular concern is that the pig isolate from Shaanxi differed by only 119 SNPs from the human E. coli isolated in this province.

Fig. 6. High genetic propensity of tet(X4)-harbouring E. coli in spreading into humans.

Phylogenetic trees of the 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli isolates together with 287 publicly available draft genomes of tet(X4)-negative E. coli (PRJNA400107) from healthy humans across China (Neighbour-Joining trees constructed based on 166,544 core-genome SNPs). Red dots represent the 95 isolates positive for tet(X4). a An unrooted tree showing the four Bayesian lineages. b A circular tree showing the corresponding information and SNP differences between isolates that are positive or negative for tet(X4). Abbreviations: AH, Anhui; BJ, Beijing; FJ, Fujian; GS, Gansu; GD, Guangdong; GX, Guangxi; GZ, Guizhou; HI, Hainan; HB, Hubei; HUN, Hunan; HN, Henan; HL, Heilongjiang; JL, Jilin; JS, Jiangsu; JX, Jiangxi; LN, Liaoning; IM, Inner Mongolia; NX, Ningxia; QH, Qinghai; SD, Shandong; SX, Shanxi; SAX, Shaanxi; SH, Shanghai; SC, Sichuan; TJ, Tianjin; XZ, Xizang; XJ, Xinjiang; Yunnan; ZJ, Zhejiang.

Discussion

Data remain scarce on the newly identified plasmid-mediated tigecycline resistance genes. Combining a national E. coli collection and advances in bioinformatics, the present study reveals a comprehensive understanding of the tet(X4) gene in E. coli from food-producing animals across China. It is evident from our data that the tet(X4) gene was present at low prevalence at the national scale in 2018, but was highly endemic in northwestern China. The observed limited genetic diversity of the isolates from northwestern China and the promiscuous plasmids carrying tet(X4) indicate recent and regional dissemination and variably successful clonal backgrounds, thus further extending our previous commentary describing the recent emergence of the tet(X4) gene in China9. Although scattered tet(X4)-positive isolates were identified in the remaining six provinces, the distinct STs and plasmids observed suggest that a parallel epidemic has coincided with the independent acquisition of tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids. Given the extensive food animal husbandry and free trade within China, these tet(X4)-harbouring “sparks” are presumably spread over a wide range of geographical scales, as exemplified by the clonal and lateral expansions in northwest China. In this context, it is worrisome to speculate that a national pandemic of tigecycline-resistant E. coli in food animals is only a matter of time unless there is timely and effective eradication of these “sparks” before the “prairie fire”.

Moreover, our concerns are escalated by the high genetic propensity of tet(X4)-positive E. coli for spreading into humans. Although the phylogenetic analysis was based on human E. coli that positive for mcr-1, there were reports of E. coli coharbouring tet(X4) and mcr-16,9,12. The high genetic similarity of E. coli between pigs and humans in the endemic region (Shaanxi province) indicates a possibility of spillover of the tet(X4) gene from animals to humans. In this circumstance, in vivo transfer of the tet(X4) gene into human pathogens would be highly likely to occur. This process might be co-selected and magnified by extensively used antibiotics in humans, such as β-lactams and aminoglycosides, as their resistant genes were observed in this study frequently accompanied by tet(X4).

The tet(X4)-harbouring plasmids resided in a wide variety of ST clones (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), but only three E. coli Bayesian lineages were implicated (Fig. 6a), thus suggesting a considerably narrow host spectrum of the plasmids carrying this gene. This is likely a similar scenario reminiscent of mcr-1, which resided primarily on IncX4 plasmids that flowed among four lineages (although diversified in 135 STs) of E. coli across China11, but it contrasts with the transmission of the blaNDM gene among eight distinct E. coli lineages in a single Chinese poultry production chain13. However, the tet(X4) gene was identified in a large proportion of multireplicon plasmids, which are diversified in replicon gene combination. This is unusual, but not without precedent in that mcr-1 has already been found in several hybrid versions of plasmids11,14,15, suggesting the involvement of plasmid fusion in the spreading of tet(X4). The presence of multiple replicons in tet(X4)-positive plasmids might prevent plasmid incompatibility16 and facilitate their interaction with a broad range of hosts17. Our plasmid resistome analysis confirmed that tet(X4)-positive plasmids are indeed versatile in spreading AMR genes. Further dissemination of these “super plasmids” into clinical settings would be a big threat. However, it remains to be seen whether the plasmids carrying tet(X4) are more prone to hybridisation, but the host ranges, the capacity to capture AMR genes, and the evolution of these new tet(X4) genetic platforms will need to be closely monitored.

Apart from a certain documented genetic environment of tet(X4), we have here expanded its habitation to a broader territory. ISCR2 was found either flanked at both ends of abh-tet(X4) or existing solely downstream of tet(X4). Different from the transposon paradigm, a single copy of the ISCR2 would transpose the adjacent sequences via rolling-circle transposition, which has been documented in the mobilization of several resistance genes18. In these circumstances, ISCR2-mediated transposition might play an essential role in the integration of tet(X4) into multiple plasmids, consequently enlarging the possibility of tet(X4) to propagate into the broad host range plasmids as well as other bacterial species. Taken together, the contribution of MGEs, in particular ISCR2, to the spread of tet(X4) gene should not be minimised.

Despite the findings, this work has several limitations that should be noted. First, we included approximately 15 E. coli randomly selected from each farm or slaughterhouse, which might not be proportional to the annual production (pig and chickens) of each province or municipality. Second, the direct screening of tet(X4) from E. coli identified without targeted tigecycline phenotype and enrichment steps might underestimate the true prevalence and diversity of E. coli carrying tet(X4), as previously seen in the detection of mcr-111. Third, the majority of the tet(X4)-positive E. coli originated from Shaanxi and Ningxia, which might have biased the deduced results.

On a national scale, the current study shows the countenance of the newly emerged tet(X4)-mediated tigecycline resistance, which is undeniably a great public health threat. Based on these results, the intervention priorities should focus on (1) the rapid and thorough eradication of this gene in food animals in northwest China, (2) tight monitoring of this gene in humans, particularly in people who are epidemiologically related to northwestern China, and (3) continuous national surveillance and risk assessment of this gene in a broader One Health approach. Furthermore, our results may also serve as a benchmark for the current status of tet(X4)-positive E. coli at an early stage, to which future survey data can be compared, thus facilitating not only the understanding of the paradigmatic shift of resistance, but also critical intervention improvements.

Methods

Strain collections

This study is based on E. coli collections from China’s national AMR surveillance programme in zoonotic bacteria. The E. coli isolates were collected and submitted by provincial laboratories or institutes certified as part of the surveillance programme. The participation of farms and slaughterhouses in the surveillance system in each province was on a voluntary basis. Commensal E. coli isolates were identified without any targeted AMR phenotypes from healthy chickens (cloacal swabs) and pigs (faecal swabs). As of July 2019, the system had received a total of 3124 E. coli isolates in 2018 originating from 233 farms and slaughterhouses across 22 of the 34 provinces and municipalities in China. Because there was a large variation in the number of isolates from each farm and slaughterhouse, we randomly selected about 15 E. coli isolates from each farm or slaughterhouse in order to minimise the sample bias in the surveillance data, and this resulted in a total of 2,475 E. coli isolated from 166 farms and slaughterhouses distributed across the country (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Since no live vertebrates were used in this study, the included E. coli collection is exempt from the IACUC approval process.

PCR-based screening of novel tet(X) variants

E. coli isolates were inoculated on MacConkey plates supplemented with tigecycline (2 mg/mL), and the resulting tigecycline-non-susceptible isolates were then subjected to tet(X) and variant screening using a two-step PCR analysis. A universal primer pair (tet(X) forward 5′-CCG TTG GAC TGA CTA TGG C-3′; tet(X) reverse 5′-TCA ACT TGC GTG TCG GTA A-3′) targeting a 475 bp conserved region of tet(X) and the four tet(X) variants was used, and the positives were further screened for tet(X3), tet(X4), and tet(X5) using primer pairs as previously described5,7. The genomic DNA of tet(X3)-carrying Acinetobacter baumannii 34AB, tet(X4)-carrying E. coli 47EC, and tet(X5)-carrying A. baumannii AB17H194 from previous studies were used as positive controls5,7.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MICs were determined for all tet(X4)-carrying E. coli using broth microdilution in Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). The tested antibiotics included tigecycline, colistin, meropenem, cefepime, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, doxycycline, and florfenicol. Susceptibility was determined according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, version 10.0, for tigecycline, colistin, and florfenicol)19 and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document (CLSI, M100-S29, for the remaining antibiotics)20. Reference strain E. coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 served as the quality control strains.

Whole-genome sequencing and assembly

All positive E. coli isolates were subjected to whole-genome sequencing. Briefly, a KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Boston, MA, US) was used for library construction, and 300-bp paired-end reads with a minimum of 150-fold coverage for each isolate were obtained following sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten System. A draft assembly of the cleaned reads was generated using SPAdes version 3.9.021. To determine the plasmid or chromosome location and the genetic environment of the tet(X4) gene, a number of isolates were selected based on phylogenetic analysis and background information regarding the source for further sequencing by ONT long-read sequencing. Briefly, libraries were prepared using the Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK004) and subjected to ONT long-read sequencing in R9.4.1 flow cells in a MinION sequencer according to the standard protocol A 0.3.4. The resulting long reads were subjected to hybrid de novo assembly in combination with Illumina short reads22.

Phylogenetic analysis

Core-genome SNP-based Neighbour-Joining phylogenetic trees were constructed for all sequenced isolates using Parsnp in the Harvest package23 with default parameter settings, and these were visualised using iTOL v524 with the corresponding features of each isolate. To determine the genetic plasticity of the tet(X4) gene in its spread into the humans, we analysed the genetic relatedness of all tet(X4)-positive E. coli in the current study together with 287 publicly available draft genomes of E. coli (PRJNA400107) that are negative for tet(X4). The negative isolates were non-duplicates and originated from human stool samples collected from healthy individuals in 2016 across China, in a previous study characterising mcr-1 carriage in humans11. A core-genome SNP tree was constructed and visualised, as described above.

Identification of STs, AMR, and virulence genes

Multi-locus sequence types (MLST) were assigned according to the E. coli MLST database25 by mapping cleaned reads to the alleles using SRST226. A minimum spanning tree based on generated sequence types was constructed in BioNumerics version 7.0 (Applied Maths) and used to differentiate the isolates in terms of their origin. Given the clinical importance of AMR and virulence in E. coli, a targeted analysis of all known acquired AMR genes and virulence-factor-associated genes was performed within our genomic dataset. These genes were screened using abricate against the ResFinder 2.127 and vfdb28 databases (>90% identity). The classification of each strain into phylogenetic groups was performed according to the scheme described previously29.

tet(X4) gene location, environment and plasmid typing

We determined the plasmid or chromosome location of the tet(X4) gene in the selected isolates by ONT long-read sequencing analysis. Contigs harbouring tet(X4) were searched and extracted from the assemblies using contig-puller (https://github.com/kwongj/contig-puller) and checked for cyclization. By searching against PlasmidFinder30 (>95% identity and >90% coverage), circular contigs harbouring plasmid replicons were considered plasmid-borne and circular contigs with no replicons detected were considered circular intermediates. All contigs were submitted to PATRIC31 for the putative coding sequences of the genes flanking tet(X4).

Statistics and reproducibility

Descriptive analysis on prevalence, 95% confidence interval and median calculation were performed using functions provided in Excel 2019 (Microsoft). Exact sample sizes for each group were described in Table 1. Source data used to plot Figs. 2–5, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 are archived in Supplementary Data 2.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank the researchers involved in the China national surveillance programme on AMR in zoonotic bacteria, and Anette Hulth at Public Health Agency of Sweden for kindly editing the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant [2018YFD0500300] and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants [31930110 and 81991535].

Author contributions

C.T.S., C.M.W., S.X.X., J.Z.S., and Y.W. designed the study and supervised the whole project. C.T.S., M.Q.C., S.Z., B.F., Z.K.L., R.N.B. and Y.X.W. conducted the screening of tigecycline-non-susceptible E. coli. S.Z., B.F., R.N.B. and Y.X.W. conducted the PCR screening, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and WGS library construction. C.T.S. interpreted the data and performed all bioinformatics analyses. C.T.S. and M.Q.C. drafted the paper. L.S., H.J.W., C.P.Z., Q.Z. and D.J.L. gave important inputs to the paper. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final paper.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are included in this article and in the Supplementary Information. Genome assemblies of the 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli have been deposited in the NCBI and are registered under BioProject accession no. PRJNA625924. All data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Chengtao Sun, Mingquan Cui.

Contributor Information

Shixin Xu, Email: 1559757434@qq.com.

Congming Wu, Email: wucm@cau.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42003-020-01148-0.

References

- 1.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (2016).

- 2.WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine. https://apps.who.int/foodsafety/publications/antimicrobials-fifth/en/ (2016).

- 3.Sun Y, et al. The emergence of clinical resistance to tigecycline. Int. J. Antimicrob. Ag. 2012;41:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuckman M, Petersen P, Projan S. Mutations in the interdomain loop region of the tet(A) tetracycline resistance gene increase efflux of minocycline and glycylcyclines. Microb. Drug Resist. 2000;6:277–282. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2000.6.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He T, et al. Emergence of plasmid mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1450–1456. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, et al. Plasmid-encoded tet(X) genes that confer high-level tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1457–1464. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0496-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, et al. Novel plasmid-mediated tet(X5) gene conferring resistance to tigecycline, eravacycline and omadacycline in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Ch. 2019;64:e01326–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01326-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai, L. et al. Detection of plasmid-mediated tigecycline-resistant gene tet(X4) in Escherichia coli from pork, Sichuan and Shandong Provinces, China. Eurosurveillance. 24, 1900340 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Sun C, et al. Plasmid-mediated tigecycline-resistant gene tet(X4) in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals, China, 2008–2018. Emerg. Microbes Infec. 2019;8:1524–1527. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1678367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, et al. Emergence of mobile tigecycline resistance mechanism in Escherichia coli strains from migratory birds in China. Emerg. Microbes Infec. 2019;8:1219–1222. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1653795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen Y, et al. Anthropogenic and environmental factors associated with high incidence of mcr-1 carriage in humans across China. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:1054–1062. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0205-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He T, et al. Co-existence of tet(X4) and mcr-1 in two porcine Escherichia coli isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:764–766. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, et al. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:16260. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun J, et al. Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:794–708. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun J, et al. Co-transfer of blaNDM-5 and mcr-1 by an IncX3-X4 hybrid plasmid in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16176. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, et al. Characterization of pMC11, a plasmid with dual origins of replication isolated from Lactobacillus casei MCJ and construction of shuttle vectors with each replicon. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;98:5977–5989. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5649-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villa L, Garcıa-Fernandez A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:2518–2529. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toleman MA, Bennett PM, Walsh TR. ISCR elements: novel gene-capturing systems of the 21st century? Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:296–316. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00048-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical breakpoints for bacteria. EUCAST. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (2019).

- 20.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twentieth Informational Supplement. M100-S29 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA, USA, 2019).

- 21.Nurk S, et al. Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads. research in computational molecular biology. Lect. Notes Comput. Sc. 2013;7821:158–170. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-37195-0_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. GenomeBiol. 2014;15:524–539. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aanensen DM, Spratt BG. The multilocus sequence typing network: mlst.net. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W728–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inouye M, et al. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med. 2014;6:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobia resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;47:D687–D692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4555–4558. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wattam AR, et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D535–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are included in this article and in the Supplementary Information. Genome assemblies of the 95 tet(X4)-positive E. coli have been deposited in the NCBI and are registered under BioProject accession no. PRJNA625924. All data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.