Abstract

Background:

Youth who are at clinical and familial risk for bipolar disorder (BD) often have significant suicidal ideation (SI). In a randomized trial, we examined whether family-focused therapy (FFT) is associated with reductions in SI in high-risk youth.

Methods:

Participants (ages 9–17 years) met diagnostic criteria for unspecified BD or major depressive disorder with active mood symptoms and had at least one relative with BD type I or II. Participants were randomly allocated to 12 sessions in 4 months of FFT or 6 sessions in 4 months of psychoeducation (enhanced care, EC), with pharmacotherapy as needed. Clinician- and child-rated assessments of mood, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and family conflict were obtained at baseline and 4-6 month intervals over 1-4 years.

Results.

Participants (N=127; mean 13.2±2.6 yrs., 82 female) were followed over an average of 105.9±64.0 weeks. Youth with high baseline levels of SI who received FFT had lower levels of (and fewer weeks with) SI at follow-up compared to youth with high baseline SI who received EC. Participants in FFT had longer intervals without suicidal behaviors than participants in EC. Youths’ ratings of family conflict significantly mediated the effects of treatment on SI at follow-up.

Limitations:

Family conflict was based on questionnaires rather than observer ratings of family interactions.

Conclusions.

Family psychoeducation with skill training can be an effective deterrent to suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth at high risk for BD. Reducing parent/offspring conflict should be a central objective of psychosocial interventions for high-risk youth with SI.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01483391

Keywords: Prevention, Psychotherapy, Suicidality, Depression, Expressed Emotion, Family Conflict

1. Introduction

Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by high rates of mood recurrence, inter-morbid depressive and mixed symptoms, and psychosocial impairment (Coryell et al. 2003; Birmaher et al., 2009). Less recognized are the high rates of suicidal ideation (SI) and attempts associated with early-onset BD and subthreshold “high-risk” conditions (Goldstein et al., 2012; Melhem et al., 2019). High levels of SI are associated with a more deteriorative course of illness in youth with BD (Birmaher et al., 2014; Weintraub et al., 2020). The present study examined whether a brief course of family-focused therapy (FFT) is effective in reducing levels of suicidal thinking and behavior in youth at high risk for BD.

In the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study, Goldstein et al. (2012) found that of 413 youth with bipolar spectrum disorders, 18% made at least one suicide attempt during a 5 year follow-up and an estimated 36% had suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation and attempts are also common in high-risk samples: offspring of parents with BD have higher rates of lifetime SI (33%) than offspring of control parents (20%; Goldstein et al., 2011). In a study of offspring of parents with severe mood disorders, 71 of 663 (10.7%) made suicide attempts over a 12-year period (Melhem et al., 2019). Clearly, suicidal thoughts, plans or behaviors – even if not imminently threatening - should be targets of treatment in the early phases of BD.

Clinical trials with adults and adolescents with or at risk for BD have found that pharmacotherapy combined with FFT - consisting of psychoeducation, communication skills training, and problem-solving skills training for patients and family members - is associated with greater reductions in mood symptom severity and recurrence in patients over time compared to pharmacotherapy with comparison treatments (Miklowitz and Chung, 2016; Miklowitz et al., 2020; Salcedo et al., 2016). In the present study, we examined whether a 4-month protocol of FFT had more beneficial effects than a brief, standardized psychoeducational treatment (Enhanced Care, EC) on the severity and frequency of SI and suicidal behaviors (i.e., self-harm or threatened self-harm with suicidal intent) among high-risk youth followed for 1-4 years. Participants were selected to have intermittent, subthreshold manic symptoms and/or lifetime episodes of major depression and at least one first- or second-degree relative with BD type I or II. Youths with these features are at substantially increased risk for conversion to syndromal BD and suicide attempts (Axelson et al., 2011).

A secondary objective of this study was to examine mediators of the effects of family intervention on SI in high-risk youths. Clinical and population-based studies have linked suicidal ideation and behavior in youth to distress, conflict, and inadequate communication in family environments (An et al., 2010; Gould et al., 1996; DeVille et al., 2020; King et al., 2001). In the COBY study, youth with SI reported significantly more conflict with their mothers, lower levels of family adaptability, and more stressful family events than those without SI (Goldstein et al., 2009; Sewall et al., 2019). Adolescents with BD who have high levels of SI are more likely to have parents rated high on expressed emotion (i.e., highly critical or emotionally overinvolved attitudes) than adolescents who have low levels of SI (Ellis et al., 2014). In the present study, we examined whether improvements in youths’ perceptions of family conflict mediated the relationship between treatment condition (FFT, EC) and reductions in SI among high-risk youth over 1-4 years.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and eligibility

The study was conducted at specialty outpatient clinics at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Semel Institute, University of Colorado (Boulder campus and Anschutz Medical Center, and Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA. At a baseline visit, all participants and parents received a full explanation of study procedures and signed university-approved informed assent and consent documents. Eligibility criteria included: (1) age between 9 years, 0 months and 17 years, 11 months; (2) meets lifetime DSM-IV and, after 2013, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013) criteria for unspecified BD or major depressive disorder; (3) living with at least one parent, stepparent or grandparent who is available for assessments and family intervention sessions; (4) has one or more first- or second-degree relatives (biological parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, grandparents) with a documentable history of BD I or II; and (5) active mood symptoms (Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS; Young et al. 1978] scores > 11 or Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised [CDRS-R; Poznanski and Mokros, 1995] scores > 29) in the 1-2 weeks prior to intake. Unspecified BD was defined as recurrent and distinct 1-3 day periods (minimum 4 hours/day) in which there was abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood plus two (three, if irritable mood only) symptoms of mania that caused a change in functioning and totaled at least 10 days in the child’s lifetime (Axelson et al. 2011).

We excluded youth who were adopted and whose biological parents could not be interviewed, had comorbid neurological illnesses or autism spectrum disorder, or had concurrent substance/alcohol abuse or dependence disorder. Participants who were already in family therapy were excluded unless they opted to discontinue their existing treatment. Youth could receive individual therapy outside of the study as long as the frequency was limited to once every 3 weeks.

2.2. Baseline Diagnostic Assessments

At the baseline study visit, trained study diagnosticians administered the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL; Chambers et al. 1985; Kaufman et al., 1997) to the child and at least one parent. Interrater reliability for KSADS Depression (Chambers et al., 1985) and Mania Rating Scale scores (Axelson et al. 2003) averaged 0.74 - 0.84 across sites. A study-affiliated child psychiatrist conducted a separate diagnostic evaluation of the child. Participants were admitted to the study once there was agreement between the KSADS interviewer and the child psychiatrist on the youth’s primary diagnosis.

A trained diagnostician administered the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan, 2016) to each parent concerning his/her own psychiatric history. In cases where first- or second-degree relatives could not be interviewed directly, diagnoses were based on secondary reports from available parents using the Family History Screening instrument (Weissman et al., 2000).

2.3. Allocation to Psychosocial Treatments

Once the child was deemed study-eligible, families were randomly allocated to FFT or EC based on a computerized dynamic allocation procedure (Begg and Iglewicz, 1980) that balanced treatment groups within sites on diagnosis (unspecified BD or MDD), age (< 13 or ≥ 13 years), and medications at study entry (mood stabilizers/antipsychotics vs. neither). FFT consisted of 12 sixty-minute sessions (8 weekly, 4 biweekly) in the 4 months following randomization. Family sessions, which included the child, parents, and siblings (whenever possible), focused on psychoeducation about managing mood disorders, communication enhancement training, and problem-solving skills training. The EC condition consisted of 3 weekly sixty-minute family psychoeducation sessions followed by 3 monthly individual psychoeducation sessions focused on implementing a mood management plan (see treatment protocols in Miklowitz et al., 2020).

Clinicians were trained to administer both psychosocial treatments and were supervised monthly by experts throughout the study. Mean Therapist Competence and Adherence Scale ratings (Marvin et al., 2016) indicated consistently high levels of fidelity to both protocols (Miklowitz et al., 2020). When pharmacological care was clinically indicated, study psychiatrists met with the child biweekly and then monthly during the study and prescribed or adjusted medications using a pharmacotherapy algorithm for this population (Schneck et al., 2017).

2.4. Clinician-Rated Outcome Assessments

Assessments of symptomatic state were conducted at baseline (covering 4 months (17 weeks) prior to randomization), every 4 months in year 1, and then every 6 months for up to 4 years. Independent evaluators (blind to treatment assignments) separately interviewed the youth and at least one parent to rate the youth’s symptoms during each week of the preceding interval using the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (A-LIFE) Psychiatric Status Ratings (PSRs; Keller et al., 1987). The weekly PSRs are 1 (asymptomatic) to 6 (fully syndromal, severe) point scales of severity and impairment associated with depression, mania, hypomania, suicidal ideation, delusions, and hallucinations. This study focused on the PSR Suicidal Ideation subscale (PSR-SI). Scores of 1 or 2 on the PSR-SI indicate no or only slight evidence of SI, whereas scores of 3 (mild; “occasional thoughts of suicide without a specific method”) or above indicate clinically significant SI. Higher scores on the PSR-SI are given for having mentally rehearsed a specific plan or making a communicative suicidal gesture (5, severe), or having made preparations for a potentially lethal suicide attempt (6, extreme) (Birmaher et al., 2014).

To help improve the parents’ and youths’ recall of the timing of mood changes or worsening of SI, evaluators presented a timeline and a calendar covering the prior 4- or 6-month period broken down by monthly intervals. Participants were asked to use landmark events (e.g., start of the school year, holidays) to assist them in tracing the youth’s mood symptoms over week-to-week intervals. Specific details of instances of suicidal thinking were elicited to understand their extent and severity. When the weekly reports of youth and parents differed, evaluators weighed all objective behavioral and subjective information to determine consensus ratings. In cases where the child reported SI that the parent did not observe, the child’s report was given more weight in consensus ratings. Interrater reliabilities for 6-point mood PSRs averaged 0.74 (intraclass r) across independent evaluators at different sites.

To further examine the severity and polarity of youths’ symptoms at each point of followup, evaluators administered the YMRS (hypo/mania) and CDRS-R (depression) to the child and one parent. The ratings covered the prior 1- and 2-week intervals, respectively.

2.5. Self-Report Outcome Assessments

Child participants filled out the 15-item Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ), Junior Version (Reynolds, 1997) at baseline and each 4-6 month follow-up. The SIQ items measure the frequency of suicidal thoughts (e.g., “I thought that others would be happier if I were dead”) over the previous month on 1 (I never had this thought) to 7 (almost every day) scales. The SIQ was validated in a study of inner-city youth between ages 11-15 years (Reynolds and Mazza, 1999), although it is routinely used with children aged 9 years and above. Total SIQ scores were tabulated for each follow-up point. Cronbach’s alpha for the SIQ was 0.96 in this study (582 ratings).

At each assessment, youth filled out the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Prinz et al., 1979), which assesses the degree of aversive communication and conflict experienced in a child/parent dyad over the prior 3 months. The 20 scale items are rated “true/false” and cover argumentativeness (e.g., “At least three times a week, we get angry at each other”), frustration in communication, empathy, and relationship quality (e.g. “I don’t think we get along very well”). Cronbach’s alpha for negatively valenced CBQ items was .87, and for positively valenced items, .90 (554 ratings). The child filled out separate CBQs regarding conflict with each primary caregiver. To standardize scores across different family constellations, we examined only the youths’ ratings of conflict with mothers, who were most frequently (115/127 or 90.6% of families) the primary caregiver.

2.5. Statistical analyses

The full range of SIQ total scores (15-105) was present at baseline (mean 37.6±22.4). Dimensional SIQ scores were log transformed to reduce negative skew. The distributions of the 1-6 PSR-SI scores were also highly negatively skewed: of 125 participants with baseline (prior 17 weeks) PSR-SI ratings, 54 (43.2%) reported at least one pre-randomization week with a clinically significant elevation in SI (PSR-SI ≥ 3). Therefore, each week of follow-up was classified as to whether or not participants had clinically significant SI during that week.

The primary analyses were conducted in four steps. In the first, we examined the differential effects of treatment (between-subjects effect), time (study visit, within-subjects effect), and the treatment by time interaction on logged SIQ scores (completed every 4-6 months up to 48 months). Mixed effect regression models (Statistical Analysis System (SAS) PROC MIXED; Ger and Everitt 2001) included random effects for subject, intercept, and slope. Given the strong association between prior SI and future SI in studies of BD (e.g., Marangell et al., 2006), we examined baseline SIQ scores and their interaction with treatment group on post-treatment SIQ scores (rated from 4 months onward). We examined both linear and quadratic effects of treatment, baseline SIQ, and time.

In the second step, we used negative binomial regression models (PROC GENMOD in SAS; Ger and Everitt, 2001) to examine differences between treatment groups on the number of weeks in each study interval with PSR-SI scores ≥ 3. These models included a dummy-coded covariate indicating whether there was an elevation on the PSR-SI (≥ 3) in one of the 17 weeks prior to randomization, and a term for the number of weeks of follow-up. In sensitivity analyses, we estimated whether treatment effects were independent of baseline differences in CDRS-R and YMRS scores, diagnosis, age, sex, or medication regimen at time of randomization. Because there were no effects of site or treatment by site interactions, we present the results with site terms removed.

In the third analytic step, we used bootstrap mediation models to examine whether there were indirect treatment effects on SI through changes in youths’ perceptions of family conflict (CBQ scores) from baseline to follow-up. Initially, we examined whether treatment group had a direct effect on CBQ scores at follow-up. Due to their severe skew, we modeled CBQ scores over time using gamma regression and estimated robust standard errors via generalized estimating equations. To model the mediation effect, SIQ scores at follow-up were regressed on lagged CBQ scores (youths’ CBQ scores from the prior assessment interval) and treatment group using mixed linear regression, fitting random intercepts and slopes within-subject. PSR-SI ratings at each follow-up (parameterized as presence vs. absence of symptoms in at least one week of the interval) were also regressed on lagged CBQ scores and treatment group using logistic regression. The bootstrapped standard errors of the estimates and percentile intervals of the indirect effects were calculated to test the effects of treatment group on SIQ scores or PSR-SI ratings via the mediator, lagged CBQ scores. All submodels within the mediation model linearly controlled for study visit. In a sensitivity analysis we tested whether mediation effects remained significant after adjusting for CDRS-R or YMRS scores concurrent to the lagged CBQ (mediator) scores.

In the fourth analytic step, we examined the frequency of suicidal events in the two treatment groups. Events were classified into three categories: actual self-harm or threats of self-harm with clear suicidal intent resulting in an inpatient admission or ER visit; instances of self-harm with unclear suicidal intent; and/or increases in weekly PSR-SI ratings to 5 or 6 (see definitions above) or on the CDRS-R Suicidal Ideation item to 6 or 7 (i.e., “Has made a suicidal attempt in the last month”) during a follow-up visit. Because we did not systematically track non-suicidal self-injurious events, we did not include them in these tabulations.

Finally, we calculated the number of weeks between randomization and the approximate date at which the first observed suicidal event occurred. We obtained Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival curves for each treatment group and tested for treatment effects using Cox Proportional Hazards models (SAS PROC PHREG), with study site as a covariate.

RESULTS

3.1. Participants

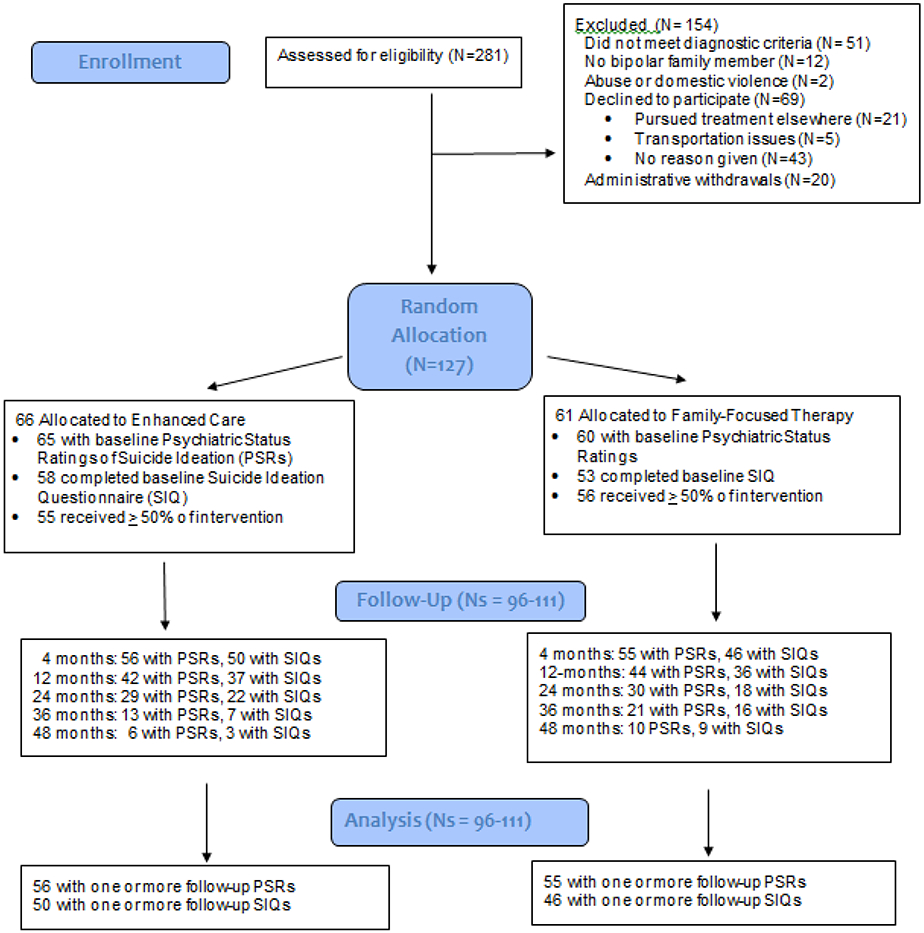

The trial included 127 participants, 75 of whom met DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder and 52 for unspecified BD. There were no differences between youth assigned to FFT and EC on any baseline variable (Table 1). Further, the 127 randomized participants did not differ on any baseline characteristic from 154 screened candidates who were found to be ineligible or refused participation (Figure 1). All participants had PSR scores of 3 (mild) or higher on the depression, mania, or hypomania subscales in the 2 weeks before randomization. Full descriptions of the recruitment strategies are available elsewhere (Miklowitz et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Demographic and Illness History Features of Youth Receiving Family-Focused Therapy for High-Risk Youth or Enhanced Care (N = 127)

| Variable | Family-Focused Therapy (N = 61) |

Enhanced Care (N = 66) | Total (N = 127) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age, years (M, SD) | 13.2 | 2.7 | 13.3 | 2.5 | 13.2 | 2.6 |

| Socioeconomic status, (M, SD) (class 1-5)a | 3.7 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 0.8 |

| Young Mania Rating Scale, baseline, (M, SD) | 12.8 | 6.8 | 12.5 | 7.7 | 12.6 | 7.3 |

| Children's Depression Rating Scale - Revised, baseline (M, SD) | 46.3 | 13.5 | 48.3 | 15.5 | 47.3 | 14.5 |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale, last 2 weeks, baseline (M, SD) | 52.7 | 9.8 | 52.2 | 22.5 | 52.5 | 10.6 |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale, most severe past episode (M, SD) | 44.5 | 7.6 | 42.8 | 8.5 | 43.6 | 8.1 |

| Suicide Ideation Questionnaire, Jr. Version, baseline, last 1 mo. | 35.7 (n=53) | 22.2 | 39.3 (n=58) | 22.7 | 37.6 (n=111) | 22.4 |

| Percentage of 17 Pretreatment Weeks with Suicidal Ideation, Psychiatric Status Ratings (%, SD)b | 18.0% | 31.0% | 21.0% | 31.0% | 19.0% | 31.0% |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 37 | 60.7 | 45 | 68.2 | 82 | 64.6 |

| Race, nonwhite, No. (%) | 12 | 19.7 | 10 | 15.2 | 22 | 17.3 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No. (%) | 15 | 24.6 | 8 | 12.1 | 23 | 18.1 |

| Primary Diagnosis, No. (%) | ||||||

| Major Depressive Disorder, No. (%) | 37 | 60.7 | 38 | 57.6 | 75 | 59.1 |

| Bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified, No. (%) | 24 | 39.3 | 28 | 42.4 | 52 | 40.9 |

| Mood polarity at study entry, No. (%) | ||||||

| Major depression, no or subthreshold hypomania, No. (%) | 51 | 83.6 | 57 | 86.4 | 108 | 85.0 |

| Hypomania, no or subthreshold depression, No. (%) | 3 | 4.9 | 4 | 6.1 | 7 | 5.5 |

| Subthreshold depression and hypomania, No. (%) | 7 | 11.5 | 5 | 7.6 | 12 | 9.4 |

| Comorbid disordersc | ||||||

| None, No. (%) | 6 | 9.8 | 11 | 16.7 | 17 | 13.4 |

| Internalizing disorders only, No. (%) | 21 | 34.4 | 26 | 39.4 | 47 | 37.0 |

| Externalizing disorders, No. (%) | 13 | 21.3 | 14 | 21.2 | 27 | 21.3 |

| Internalizing and externalizing disorders, No. (%) | 21 | 34.4 | 15 | 22.7 | 36 | 28.4 |

| Suicide Attempt in last 12 mos., No (%)d | 9 (53) | 17.0 | 7 (of 50) | 14.0 | 16 (of 103) | 15.5 |

| Baseline medications | ||||||

| None, No. (%) | 23 | 37.7 | 33 | 50.0 | 56 | 44.1 |

| Lithium, No. (%) | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Antipsychotic, No. (%) | 13 | 21.3 | 17 | 25.8 | 30 | 23.6 |

| Anticonvulsant, No. (%) | 10 | 16.4 | 8 | 12.1 | 18 | 14.2 |

| Antidepressant, No. (%) | 27 | 44.3 | 20 | 30.3 | 47 | 37.0 |

| Anxiolytic, No. (%) | 2 | 3.3 | 2 | 3.0 | 4 | 3.1 |

| Psychostimulant/other ADHD agent, No. (%) | 12 | 19.7 | 14 | 21.2 | 26 | 20.5 |

| Family Composition | ||||||

| Both biological parents, intact family, No. (%) | 32 | 52.5 | 30 | 45.5 | 62 | 48.8 |

| Both biological parents, joint custody, No. (%) | 6 | 9.8 | 5 | 7.6 | 11 | 8.7 |

| One biological parent without stepparent, No. (%) | 7 | 11.5 | 14 | 21.2 | 21 | 16.5 |

| One biological parent plus stepparent, No. (%) | 9 | 14.8 | 11 | 16.7 | 20 | 15.7 |

| Grandparent or other relative, No. (%) | 7 | 11.5 | 6 | 9.1 | 13 | 10.2 |

| Family History of Bipolar Disorder | ||||||

| Youth with first-degree relatives only, No. (%) | 35 | 57.4 | 47 | 71.2 | 82 | 64.6 |

| Youth with second-degree relatives, No. (%) | 10 | 16.4 | 9 | 13.6 | 19 | 15.0 |

| Youth with first- and second-degree relatives, No. (%) | 16 | 26.2 | 10 | 15.2 | 26 | 20.5 |

Higher class values for socioeconomic status indicate higher educational level and occupation.

Weeks with suicidal ideation refer to the proportion of the 17 weeks prior to random allocation in which PSR Suicidal Ideation scale items were rated 3 (mild) or above.

Youth with internalizing comorbid disorders had anxiety disorders and/or eating disorders. Youth with externalizing disorders had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, alone or in combination.

Suicide attempts were defined as any self-harm event or threatened self-harm that required a visit to a hospital emergency room and/or resulted in hospitalization, and/or increases on the Psychiatric Status Rating Scale of Suicidal Ideation to 5 or 6 for at least one follow-up week, or increases on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised Suicide item to 6 or 7 (1-7 scale of severity) for at least 2 follow-up weeks.

Fig. 1. Consort Flow Diagram.

Abbreviations: PSR = Psychiatric Status Ratings for the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation; SIQ = Suicide Ideation Questionnaire

Of 127 subjects (82 female; mean age 13.3±2.6 years), 125 had pretreatment PSR-SI scores (covering the 17 weeks before randomization) and 111 (87.4%) completed baseline SIQs (covering the prior month), with no differences between those who did and did not complete the questionnaire on sex, age, ethnicity, race, or treatment allocation. The median duration of follow-up was 105.9±64.0 weeks (range 0–255 weeks), with no differences between treatment conditions on follow-up duration.

Of 125 participants, 88 (70.4%) had at least one study pharmacotherapy visit at followup, with no treatment group differences (FFT: M=9.0±5.0 visits; EC: M=7.6±5.0 visits). Patients in FFT attended an average of 11.0±3.4 of 12 (91.7%) protocol therapy sessions, whereas those in EC attended an average of 5.5±2.4 of 6 (91.7%) protocol sessions. There were no group differences in attrition from therapy. At study entry, 37.0% (47/127) of the families reported that one or more members (parents or child) had received psychosocial intervention services in the 4 months prior to intake. The treatment groups did not differ at baseline or any point of follow-up in the receipt of psychosocial services outside of the study.

3.2. Effects of Treatment Group on SIQ and PSR-SI scores

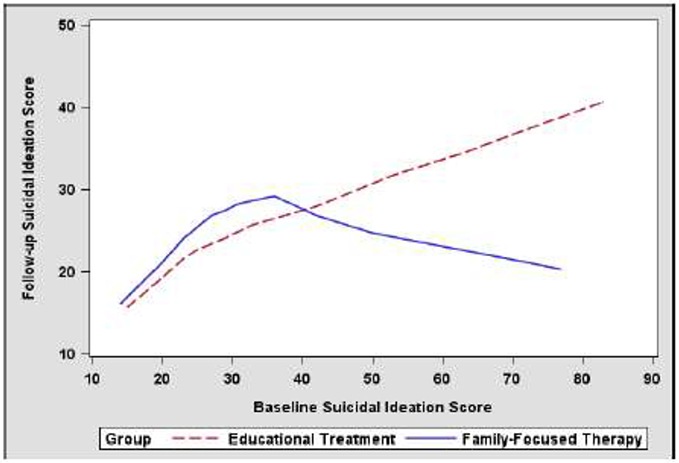

The treatment groups did not differ on baseline SIQ scores or in the proportion of youth who had made a suicide attempt in the 12 months prior to study entry (9 in FFT [17.0%), 7 in EC [14.0%]; Table 1). Results of the first mixed effect regression model indicated a main effect of treatment group (F[1,205]=7.13, p=0.008) and baseline SIQ scores (F[1, 205]=36.08, p<0.0001) on follow-up SIQ scores (4 month study visit and later), but no effect of study visit. Additionally, there was an interaction between treatment group and baseline SIQ scores on follow-up SIQ scores (F[1,205]=8.68, p=0.004). Post-hoc examination of the interaction revealed a significant and positive relationship between baseline SIQ and follow-up SIQ scores in the EC group (Standardized β=0.30, p < 0.0001) and a nonsignificant relationship (Standardized β=0.08, p=0.07) in the FFT group (see Figure 2). Thus, youth with high baseline SIQ scores who received EC had a less favorable trajectory of follow-up SIQ scores compared to youth with high baseline SIQ scores who received FFT.

FIG 2. Baseline Suicide Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) Scores as a Predictor of Follow-up SIQ Scores in Youth at High Risk for Bipolar Disorder: Effects of Family-Focused Treatment versus Enhanced Care Treatment.

The linear effects of treatment group (F[1,203]=6.73, p=.01) and the baseline SIQ by treatment interaction (F[1, 203)=9.36, p=0.003) remained significant when we included quadratic terms in the model. Additionally, the effects of treatment, baseline SIQ, and their interaction on follow-up SIQ scores remained significant when including sex, age, baseline diagnosis (MDD vs. BD-NOS), comorbid disorders (presence of ADHD or anxiety disorders), or medication regimens (at baseline or any point of follow-up) as covariates.

Results of a negative binomial regression model (second analytic step) indicated that participants in EC had a higher rate of post-randomization weeks with clinically significant SI on the PSR-SI scale (scores ≥ 3; incidence rate ratio=2.47, 95% CI: 1.15 to 5.34; Wald X2(1)=5.32, p=0.02) compared to participants in FFT. There were no group differences in number of pre-randomization weeks with elevated PSR-SI scores (Table 1).

As expected, there was a main effect of baseline CDRS-R total scores on follow-up SIQ scores (F[1,269]=24.19, p<0.0001). With baseline CDRS-R scores covaried, the effect of treatment group (F[1,269]=4.87, p=0.028) and the interaction between baseline SIQ scores and treatment group remained significant in predicting post-treatment SIQ scores (F[1,269]=5.96, p=0.015). There was no relationship between baseline YMRS scores and follow-up SI scores.

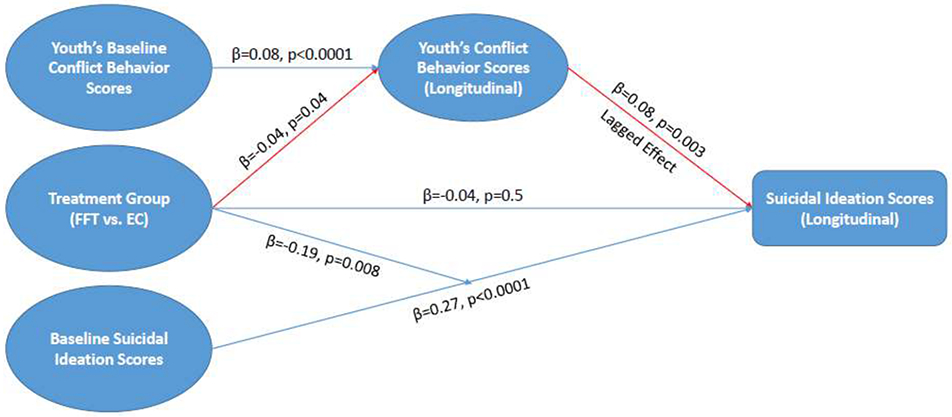

3.4. Mediation Models

In the third analytic step, we examined the effects of treatment group on both SIQ and PSR-SI scores, with youth’ perceptions of family conflict (CBQ instrument) as the mediator. Participants rated CBQs on their mothers in 58 of 66 families in EC (87.9%) and 57 of 61 families in FFT (93.4%), with no group differences in baseline levels of conflict with mothers.

At baseline, youth who rated the mother/child relationship as more conflictual on the CBQ reported higher SIQ scores than those who rated the relationship as less conflictual (r(97)=0.36, p< 0.0002). After controlling for baseline CBQ scores and study visit, there was a significant effect of treatment group on the mediator - repeated child-rated CBQ scores at follow-up - indicating that youth in FFT perceived significantly less conflict with their mothers over time than youth in EC (Z=2.02, p=0.04; see Figure 3). There was no interaction between treatment group and baseline CBQ scores on follow-up CBQ scores.

Fig. 3. Changes in Youths’ Perceptions of Family Conflict as a Mediator Between Treatment Group (FFT vs. EC) and Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Scores.

There were significant lag-effects of CBQ scores (the mediator) on self-rated SIQ scores and clinician-rated PSR-SI scores, such that youth with higher perceived conflict in one assessment interval reported significantly more suicidal ideation in the next interval (SIQ: t=3.01, p=0.003; PSR-SI: z=2.91, p=0.004). The direct effects of treatment group on SIQ and PSR-SI scores were nonsignificant after accounting for lagged CBQ scores, baseline SIQ, and study visit; however, there remained a significant interaction between treatment group and baseline SIQ on follow-up SIQ scores. The indirect effects of treatment group on SIQ and PSR-SI scores at follow-up via the mediator (lagged CBQ scores) were significant, using both parametric testing with bootstrapped standard errors (p=0.02 for both SIQ and PSR-SI) and nonparametric testing via the 95% bootstrap percentile interval of the indirect effect (full intervals < 0 for both SIQ and PSR-SI). Thus, lagged CBQ scores significantly mediated the associations between treatment group and SI at follow-up as measured by both the SIQ and PSR-SI.

When concurrent CDRS-R scores were covaried, the lagged CBQ scores still significantly mediated the effect of treatment group on follow-up SIQ scores (full bootstrap interval < 0, p=0.036), although the mediation effect on follow-up PSR-SI fell to marginal significance (p=0.057). Interactions between CDRS-R scores and the treatment and mediator effects were each nonsignificant.

3.5. Time to Suicidal Events

Of the 111 participants with at least one follow-up visit (Figure 1), 25 (22.3%) had one or more suicidal events during the study, 16 (24.2%) in EC and 9 (13.6%) in FFT. Ten of these participants required an inpatient stay or an ER visit for self-harm or threatened self-harm with explicit suicidal intent, 6 had instances of self-harm with unclear intent (2 hospitalized, 1 ER visit), and 9 had significant elevations lasting at least one week on the PSR- or CDRS-R SI subscales to levels usually associated with suicide attempts.

A Cox Proportional Hazards model indicated that youth in FFT had longer times without a suicidal event (M=125.0 weeks, SE=6.0) than youth in EC (M=114.3 weeks, SE= 7.8; log-rank X2(1)=4.61, p=0.03; HR=0.41; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.98), with no independent effects of study site. In sensitivity analyses, we examined the narrower category of youths who engaged in self-harm or threats of self-harm with explicit suicidal intent. Of the 10 youth in this category, 8 were in EC (M=133.2 weeks to event, SE=5.7) and 2 were in FFT (M=140.1 weeks, SE=2.9), suggesting a higher survival rate in the FFT group (log-rank X2(1)=5.58, p=0.02, HR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.73).

4. Discussion

Randomized trials consistently indicate that when combined with pharmacotherapy, FFT is associated with an improved trajectory of mood symptoms in adults and adolescents with BD. The randomized clinical trial on which this study was based found that, among symptomatic youth at high familial risk for BD, FFT was associated with longer well intervals prior to new mood episodes than EC (Miklowitz et al., 2020). In the present study, high-risk youth with high baseline levels of SI who received FFT showed greater reductions in SI over 1-4 years than those who received EC. The effects of psychosocial treatment on SI scores appeared to be mediated by changes in the youths’ perceptions of family conflict.

Among youth who had lower levels of SI at baseline, no treatment group differences emerged in the trajectory of SIQ scores at follow-up. Among youth in the upper half of the SIQ distribution, those in EC showed higher SIQ scores throughout follow-up than those in FFT. Similar findings emerged from a randomized trial of adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis, which found that FFT was associated with greater improvement in subthreshold psychosis symptoms among those individuals who began with higher clinical risk for psychotic episodes (Worthington et al. 2020). Thus, FFT may be indicated for high-risk individuals who are more severely ill at intake.

Youth in FFT had longer periods of wellness without suicidal events (e.g., attempts or threatened attempts with clear suicidal intent) than youth in EC. However, we were underpowered to examine self-harming behavior in its various forms. Suicide attempts are strongly influenced by factors not examined in this study, such as comorbid substance or alcohol abuse or a history of childhood abuse (Bridge et al., 2006). The longevity of effects of brief family interventions on suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury deserves study in high-risk samples that vary on these potential effect modifiers.

A key question about FFT has been its mechanisms of action – whether improvements in family environments are essential to the clinical benefits of patients. Prior trials have found that FFT is associated with greater improvements in positive family processes (e.g., self-reported family cohesion, number of positive or constructive statements expressed by parents or offspring in family interactions) and greater reductions in family conflict than briefer psychoeducational interventions (Simoneau et al., 1999; Sullivan et al., 2012; O’Brien et al., 2014). In the present study, we found that there were greater reductions in youths’ ratings of mother-child conflict in FFT than in EC. Further, treatment-associated reductions in youths’ perceived conflict behavior scores were associated with (and temporally preceded) lower levels of self-rated and clinician-rated SI in successive study intervals. Although FFT does not specifically focus on suicidal thinking or behavior, its emphasis on encouraging family members to understand and empathize with the offspring’s mood symptoms may lead to reductions in dyadic conflict, which in turn may protect youths from a subsequent worsening of suicidal thinking.

It is often assumed that greater family conflicts anticipate increases in SI (as would be suggested by results from this study), but severity of SI and other mood symptoms in patients with BD are strong predictors of stress, burden, depression and health problems in primary caregivers (Chessick et al., 2007, 2009). Parents of children with bipolar spectrum disorders report more stress than parents of children with non-bipolar diagnoses, especially when parents have depression themselves (Perez Algorta et al., 2018). Parents and other caregivers may become frustrated and desperate when attempting to help patients manage their suicidal thoughts or behaviors, and greater caregiver-patient conflict or criticism may result from this frustration. Indeed, analyses of family interactions in patients with mood and psychotic disorders suggest that the frequency of parent/offspring criticism is strongly related to the degree of negativity expressed by offspring (Miklowitz, 2004). For youth at high risk for BD, focusing treatment on family communication during and following symptomatic periods may reduce the risk of SI in youth and levels of burden and distress in parents.

5. Limitations

Because SI data are typically collected after the fact, there is always a risk of retrospective bias in self-reports. We made every attempt to reduce bias by gathering explicit details of the instances of SI to enhance recall, but it is likely that some instances were not reported. Additionally, negative mood states are likely to influence youths’ reports of SI and levels of conflict with parents. The observed associations between changes in perceived conflict and SI remained significant when we included concurrent levels of depression in longitudinal regression models. Nonetheless, we would be more confident in our mediational findings had they been based on changes in observable family interactions rather than changes in self-report measures of family conflict.

Second, although baseline medication regimens were included as a stratification variable in the random allocations to treatments, we cannot rule out the effects of changes in pharmacotherapy on these findings. Psychosocial treatments should be evaluated in randomized designs where youth with or at risk for BD are allocated to specific medication regimens (e.g., mood stabilizers or second generation antipsychotics with vs. without antidepressants). Third, the FFT and EC treatments were matched on duration of treatment (4 months) but the EC condition contained fewer sessions than the FFT condition (6 versus 12), and only 3 of these sessions involved family members. Thus, the more frequent family contact in FFT may have contributed to the youth’s perceptions of reduced conflict with caregivers.

Fourth, we did not assess whether the high risk youth were at risk for personality disorders as well as mood disorders. The reliability of personality disorder diagnoses tends to be low in the age group we sampled (mean 13.3 years; Guilé, Boissel, Alaux-Cantin, & Garny de La Rivière, 2018). We see value in studies examining the effects of family intervention on SI in older adolescents and young adults with early signs of personality disorders.

6. Conclusions

Together with the primary results from this trial (Miklowitz et al., 2020), we conclude that FFT given during a period of mood exacerbation may reduce the severity and recurrence of mood episodes and SI among youth with clinical and familial vulnerability to BD. Future studies are needed to clarify the subgroups of patients (other than those with initially high SI scores) that are most likely to show treatment-related improvements in suicidal thinking or behavior. Further, the FFT protocol described here is brief. Possibly, even stronger effects on SI would come from supplementing the 12-session FFT protocol with booster sessions, or enhancing it with individual or group sessions focused on distress tolerance or mindfulness skills (Linehan and Wilks 2015; Goldstein et al., 2015).

Highlights.

In a randomized trial, family-focused therapy was effective in reducing suicidal ideation and behaviors in youth at high risk for bipolar disorder over 1-4 years.

Changes in family conflict mediated the relation between psychosocial treatments and suicidal ideation scores at follow-up.

Family skill training should be considered as a preventative strategy for youth in the early phases of bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the following individuals for providing administrative support and study diagnostic or follow-up evaluations: Tenah Acquaye, BA, Laura Anderson, MA, Casey Armstrong, MA, Addie Bortz, BA, Amethyst Brandin, BA, Daniella DeGeorge, BA, Anna Frye, BA, Kathryn Goffin, BA, Brittany Matkevich, BA, Jennifer Pearlstein, MA, Meagan Whitney, BA, and Natalie Witt, BA. We thank the following clinicians for providing study treatments: Melissa Batt, MD, Emily Carol, PhD, Victoria Cosgrove, PhD, Alissa Ellis PhD, Elizabeth L. George, PhD, Christopher Hawkey, PhD, Meghan Howe, LCSW, MSW, Jasmine Fayeghi, PsyD, Marcy Forgey Borlik, MD, Amy Friedman, LCSW, Daniel Johnson, PhD, Danielle Keenan-Miller, PhD, Barbara Kessel, DO, Mikaela Kinnear, PhD, Daniel Leopold, MA, Jessica Lunsford-Avery, PhD, Susan Lurie, MD, Sarah Marvin, PhD., Luciana Massaro, MA, Zachary Millman, MA, Ryan Moroze, MD, Dan Nguyen, MD, Andrea Pelletier-Baldelli, PhD, Izaskun Ripoll, MD, Rochelle Rofrano, BA, Christopher Rogers, MD, Lela Ross, MD, Donna J. Roybal, MD, Robert L. Suddath, M.D., Aimee E. Sullivan, Ph.D., and Dawn O. Taylor, PhD. Independent fidelity ratings of therapy sessions were provided by Eunice Y. Kim, PhD. The following are acknowledged for providing consultation on study procedures, pharmacotherapy protocols and statistical analyses David Axelson, MD, Boris Birmaher, MD Melissa DelBello, MD, MS, Amy Garrett, PhD, Antonio Hardan, MD, Gerhard Helleman, PhD, Judy Garber, PhD, Amie Noelle-Swanson, PhD, and Catherine Sugar, Ph.D.

This study was reviewed and continuously approved by the institutional review boards at the UCLA Semel Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine, and the University of Colorado (Boulder and Anschutz Medical Campus).

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported in part by grants R01MH093676 (Drs. Miklowitz and Schneck) and R01MH093666 (Dr. Chang) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Miklowitz receives research support from the NIMH, the Danny Alberts Foundation, the Attias Family Foundation, the Carl and Roberta Deutsch Foundation, the Kayne Family Foundation, AIM for Mental Health, and the Max Gray Fund; and book royalties from Guilford Press and John Wiley and Sons. Mr. Merranko reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Weintraub reports research support from AIM for Mental Health. Drs. Walshaw receives research support from Bluebird Biotech and Second Sight. Dr. Singh receives research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute, NIMH, National Institute of Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, and the Brain and Behavior Foundation. She is on the advisory board for Sunovion and is a consultant for Google X and Limbix. Dr. Chang is a consultant on the speaker’s bureau for Sunovion. Dr. Schneck receives research support from the NIMH and the Ryan White Foundation.

References

- Algorta GP, Youngstrom EA, Frazier TW, Freeman AJ, Youngstrom JK, Findling RL, 2011. Suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder: predictor or outcome of family processes and mixed mood presentation? Bipolar Disord., 13, 76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Ahn JH, Bhang SY, 2010. The association of psychosocial and familial factors with adolescent suicidal ideation: a population-based study. Psychiatr. Res, 177, 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Ed. (Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, D. C., American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.) (DSM-5). Washington, D. C., American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B Brent D, Wassick S, Hoover C, Bridge J and Ryan N, 2003. A preliminary study of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children mania rating scale for children and adolescents. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol. 13, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J and Keller M 2006. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 63, 1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Ha W, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt JI, Liao F, Iyengar S, Dickstein D, Kim E, Ryan ND, Frankel E, Keller MB, 2011. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 50, 1001–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB and Iglewicz B, 1980. A treatment allocation procedure for sequential clinical trials. Biometrics, 36, 81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D Goldstein B Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, Houck Ha PWS Iyengar, Kim E, Yen S, Hower H, Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein T, Ryan N and Keller M, 2009. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am. J. Psychiatry, 166, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Gill MK, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Goldstein TR, Yu H, Liao F, Iyengar S, Diler RS, Strober M, Hower H, Yen S, Hunt J, Merranko JA, Ryan ND, Keller MB, 2014. Longitudinal trajectories and associated baseline predictors in youths with bipolar spectrum disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry, 171, 990–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA, 2006. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry, 47, 372–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, and Davies M, 1985. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semi-structured interview: test-retest reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 42, 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessick CA, Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Dickinson LM, Allen MH, Morris CD, Gonzalez JM, Marangell LB, Cosgrove V, Ostacher M and the STED-BD Family Experience Collaborative Study Group, 2009. Suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among bipolar patients as predictors of the health and well-being of caregivers. Bipolar Disord., 11, 876–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessick CA, Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Kaczynski R, Allen MH, Morris CD, Marangell LB, and the STED-BD Family Experience Collaborative Study Group, 2007. Current suicide ideation and prior suicide attempts of bipolar patients as influences on caregiver burden. Suic. Life Threat. Behav, 37, 482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, Keller M, Leon AC, Endicott J, Schettler P, Judd L, Mueller T 2003. The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 60, 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVille DC, Whalen D, Breslin FJ, Morris AS, Khalsa SS, Paulus MP, and Barch DM, 2020. Prevalence and family-related factors associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-injury in children aged 9 to 10 years. JAMA Network Open, 3(2), e1920956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AJ, Portnoff LC, Axelson DA, Kowatch RA, Walshaw P, and Miklowitz DJ, 2014. Parental expressed emotion and suicidal ideation in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr. Res, 216, 213–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ger D, and Everitt BS, 2001. Handbook of Statistical Analyses Using SAS, Second Edition. London: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Gill MK, Esposito-Smythers C, Ryan ND, Strober MA, Hunt J, and Keller M, 2009. Family environment and suicidal ideation among bipolar youth. Arch. Suic. Res, 13, 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Fersch-Podrat RK, Rivera M, Axelson DA, Merranko J, Yu H, Brent D, and Birmaher B, 2015. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for adolescents with bipolar disorder: results from a pilot randomized trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol, 25, 140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Liao F, Gill MK, Ryan ND, Yen S, Hunt J, Hower H, Keller M, Strober M, and Birmaher B, 2012. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 69, 1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Obreja M, Shamseddeen W, Iyengar S, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Kupfer DJ, Brent DA, Birmaher B, 2011. Risk for suicidal ideation among the offspring of bipolar parents: results from the Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS). Arch. Suic. Res. 15, 207–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D, 1996. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 53, 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilé JM, Boissel L, Alaux-Cantin S, Garny de La Rivière S 2018. Borderline personality disorder in adolescents: prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment strategies. Adolescent Health and Medical Therapeutics, 23(9), 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Goldstein T, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Iyengar DS, Brent D, Kupfer D, Birmaher B (2016). Toward the definition of a bipolar prodrome: dimensional predictors of bipolar spectrum disorders in at-risk youths. Am. J. Psychiatry, 173, 695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N, 1997. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 36, 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC, 1987. The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 44, 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RA, Schwab-Stone M, Flisher AJ, Greenwald S, Kramer RA, Goodman SH, Lahey D, Shaffer D, Gould MS, 2001. Psychosocial and risk behavior correlates of youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 40, 837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Wilks CR, 2015. The course and evolution of dialectical behavior therapy. Am. J. Psychotherapy, 69, 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangell LB, Bauer M, Dennehy EB, Wisniewski SR, Allen M, Miklowitz DJ, Oquendo M, Frank E, Perlis R, Martinez JM, Fagiolini A, Otto MW, Chessick C, Zboyan HA, Miyahara S, Sachs GS, Thase ME, 2006. Prospective predictors of suicide and suicide attempts in 2000 patients with bipolar disorders followed for 2 years. Bipolar Disord., 8, 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin SE, Miklowitz DJ, O'Brien MP, Cannon TD, 2016. Family-focused therapy for youth at clinical high risk of psychosis: treatment fidelity within a multisite randomized trial. Early Interv. Psychiatry, 10, 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Porta G, Oquendo MA, Zelazny J, Keilp JG, Iyengar S, Burke A, Birmaher B, Stanley B, Mann JJ, Brent DA, 2019. Severity and variability of depression symptoms predicting suicide attempt in high-risk individuals. JAMA Psychiatr., 76, 603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, 2004. The role of family systems in severe and recurrent psychiatric disorders: a developmental psychopathology view. Dev. Psychopathol, 16, 667–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Chung BD, 2016. Family-focused therapy for bipolar disorder: reflections on 30 years of research. Family Proc., 55, 483–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Wisniewski SR, Kogan JN, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Gyulai L, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Shirley ER, Thase ME, Sachs GS, 2007. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 64, 419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Singh MK, Taylor DO, George EL, Cosgrove VE, Howe ME, Dickinson LM, Garber J, and Chang KD, 2013. Early intervention for symptomatic youth at risk for bipolar disorder: a randomized trial of family-focused therapy, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 52: 121–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Walshaw PD, Singh MK, Sullivan AE, Suddath RL, Forgey Borlik M, Sugar C, Chang KD, 2020. Effects of family-focused therapy vs enhanced usual care for symptomatic youths at high risk for bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, January 15, doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4520 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MP, Miklowitz DJ, Candan KA, Marshall C, Domingues I, Walsh BC, Zinberg JL, De Silva SD, Woodberry KA, and Cannon TD, 2014. A randomized trial of family focused therapy with youth at clinical high risk for psychosis: effects on interactional behavior., J Consult Clin Psychol., 82: 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Algorta G, MacPherson HA, Youngstrom EA, Belt CC, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Taylor HG, Birmaher B, Horwitz SM, Findling RL, Fristad MA, 2018. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with bipolar spectrum disorders. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychology, 47 (suppl. 1), S306–S320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Dennehy EB, Miklowitz DJ, DelBello MP, Calabrese JR, Wisniewski SR, Bowden CL, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, 2009. Retrospective age-at-onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during 2-year follow-up: Results from the STEP-BD study. Bipolar Disord., 11, 391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB, 1995. Children's Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) Manual. Los Angeles, CA., Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Foster SL, Kent RN, O’Leary KD, 1979. Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. J. Applied Behav. Analysis, 12, 691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, 1997. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire, Jr. (SIQ-JR). Lutz, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ, 1999. Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR. School Psychol. Rev. 28, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo S, Gold AK, Sheikh S, Marcus PH, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T, Sylvia LG, 2016. Empirically supported psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: Current state of the research. J. Affect. Disord, 201, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneck CD, Chang KD, Singh MK, Delbello MP, Miklowitz DJ, 2017. A pharmacologic algorithm for youth who are at high risk for bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol., July 21, doi: 10.1089/cap.2017.0035 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewall CJR, Goldstein TR, Salk RH, Merranko J, Gill MK, Strober M, Keller MB, Hafeman D, Ryan ND, Yen S, Hower H, Liao F, Birmaher B, 2019. Interpersonal relationships and suicidal ideation in youth with bipolar disorder. Arch. Suic. Res, July 3, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1616018 (Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, 2016. MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview: Child and Adolescent Version for DSM-5. Tampa, FL., Harm Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau TL, Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA, Saleem R, George EL, 1999. Bipolar disorder and family communication: Effects of a psychoeducational treatment program. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 108, 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AE, Judd CM, Axelson DA, Miklowitz DJ, 2012. Family functioning and the course of adolescent bipolar disorder. Behav. Therapy, 43, 837–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub MJ, Schneck CD, Axelson DA, Kowatch R, Birmaher B, Miklowitz DJ, 2020. Classifying mood symptom trajectories in adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 59, 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, Olfson M, 2000. Brief screening for family psychiatric history: the family history screen. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 57, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington MA, Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien M, Addington J, Bearden CE, Cadenhead KS, Cornblatt BA, Mathalon DH, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Cannon TD, 2020. Selection for psychosocial treatment for youth at clinical high risk for psychosis based on the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study individualized risk calculator. Early Interv. Psychiatry, January 14, doi: 10.1111/eip.12914 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA, 1978. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry, 133, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]