Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether a short course of tamoxifen decreases bothersome bleeding in etonogestrel contraceptive implant users.

Methods

In a 90-day double-blind randomized control trial, we enrolled etonogestrel implant users with frequent or prolonged bleeding or spotting. A sample size of 40 per group (N=80) was planned to compare 10 mg tamoxifen or placebo twice daily for 7 days after 3 consecutive days of bleeding or spotting no more than once per 30 days (maximum 3 treatments). Participants then entered a 90-day open label study where all received tamoxifen if needed every 30 days (maximum 3 treatments). Participants used text messages to record daily bleeding patterns. Our primary outcome was the total number of consecutive amenorrhea days after the first treatment. Secondary outcomes included time to bleeding or spotting cessation and restart after first treatment, overall bleeding patterns, and satisfaction.

Results

From January 2017 to November 2018, 112 women enrolled in the study; 88 (79%) completed 90 days, and 79 (71%) completed 180 days. Participant characteristics did not differ between groups; mean age 24, majority identified as White not Hispanic with at least some college education. After the first treatment, the tamoxifen group reported an average of 9.8 (95% CI: 4.6–15.0 ) more consecutive days of amenorrhea and more total days of no bleeding (amenorrhea or spotting) in the first 90-days [median 73.5 (range 24–89) vs 68 (range 11–81), p = 0.001]. The placebo group showed a similar treatment benefit after first active use of tamoxifen in the open label phase. At the end of the randomized study (first 90 days), women who received tamoxifen reported higher satisfaction [median 62 mm (range 16–100)] than those treated with placebo [46 mm (range 0–100); p = 0.023].

Conclusion

A short course of tamoxifen reduces problematic bleeding and improves satisfaction in users of etonogestrel implants.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

Précis

A short course of tamoxifen reduces breakthrough bleeding related to the contraceptive implant.

Introduction

Increasing the uptake, acceptability, and continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods could decrease the incidence of unintended pregnancy.1 Unacceptable bleeding patterns experienced by some users of the etonogestrel contraceptive implant impact the acceptability and continuation of this LARC method.2 Although the Center for Disease Control Selected Practice Recommendations (CDC SPR) provides evidence-based guidelines for management of bleeding irregularities for implants, these recommendations primarily reflect expert opinion and not high quality evidence.3 As such, clinicians lack guidance for effective management of this problematic bleeding.

Prior studies have demonstrated that tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, might be useful. In a randomized study of etonogestrel implant users with problematic bleeding, Simmons and colleagues found a clinically-important reduction in the number of bleeding and spotting days in the first 30 days after treatment among users who received a 7-day course of tamoxifen compared to placebo (mean difference 5 days).4 A prior study of tamoxifen in levonorgestrel implant users showed similar results.5 The sustained post-treatment improvement in implant bleeding patterns with tamoxifen appears novel, as prior studies of other pharmacologic therapies (such as combined oral contraceptives) have only demonstrated improvement during maintenance of therapy.6,7 However, despite these encouraging short-term results, we do not know if this short course of tamoxifen results in a sustained benefit past 30 days, or if repeating the dose provides similar results.

To further evaluate the potential of tamoxifen as a management strategy for problematic implant bleeding, we designed a study to determine the longevity of the tamoxifen effect and the response to repeat dosing. We hypothesized that a 7-day treatment of tamoxifen would result in a significantly longer bleeding-free interval than placebo. To increase our ability to demonstrate a prolonged effect with tamoxifen, we enrolled women in a 90-day randomized placebo-controlled study, followed by a 90-day open-label active treatment interval for all participants.

Methods

We conducted this study at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in Portland, OR, USA and the University of Hawaii (UH) in Honolulu, HI, USA, from January 2017 to May 2019. The Institutional Review Board at OHSU approved the study protocol and the UH Institutional Review Board ceded authority to OHSU. We recruited women aged 15–45 years old using the etonogestrel 68-mg subdermal contraceptive implant (Implanon or Nexplanon, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) for at least 30-days who met criteria for frequent or prolonged bleeding or spotting during the previous month. Women under the age of 18 were consented in tandem with a parent or guardian who cosigned the consent form. We defined ‘frequent’ as two or more independent bleeding or spotting episodes and ‘prolonged’ as seven or more consecutive days of bleeding or spotting in a 30-day interval. We considered all reported bleeding or spotting events as unscheduled, as etonogestrel implant users do not have normal menstrual cyclicity. Our exclusion criteria included being < 6 months postpartum, < 6 weeks post abortion, currently breast-feeding, undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding predating placement of the implant, bleeding dyscrasia (known or patient reported), anticoagulation use, active cervicitis, history of venous thromboembolism, history of breast or uterine malignancy, current implant in situ longer than 2 years 8 months or other contraindications including medication interactions or precautions to tamoxifen.8 Subjects agreed to not use other hormonal therapy for management of bleeding during participation, and we required a 6 weeks wash out for other hormonal therapy prior to study enrollment.

Subjects completed an in-person screening visit to confirm implant use, a pelvic exam to rule out other causes of bleeding or spotting, cervical cytology (if indicated), and gonorrhea and chlamydia testing. We repeated gonorrhea and chlamydia testing during the study if a subject reported a new sexual partner. We also performed urine pregnancy tests at baseline, enrollment, and at study exit or if there was a concern for pregnancy. Study staff used a calendar to help subjects estimate the number of bleeding or spotting and amenorrhea days over the preceding 90-days or since their implant was placed to establish an estimate of baseline bleeding patterns. Subjects completed a visual analog scale (VAS) (0–100 mm) at baseline, after the first treatment, at the beginning of the open label study, and at study exit to assess satisfaction with current bleeding pattern and implant use overall.

The study involved two phases: 1) a randomized, double blind placebo-controlled trial over a 90-day reference period that started at the initiation of treatment 1 where women received either tamoxifen 10 mg twice daily for 7 days or an identical placebo; 2) An open label phase over a second 90-day reference period where both study arms received tamoxifen. Subjects received the first supply of study drug at enrollment, and we dispensed additional study drug at visits 14–25 days after taking treatment. We instructed participants to start study drug the next time they experienced three consecutive days of bleeding or spotting (initiating drug on the third day) or immediately if they had been bleeding or spotting for at least consecutive 3 days at the time of enrollment. If subjects reported no bleeding or spotting in the first 30 days after enrollment, we withdrew the subject from the study. At follow up visits, participants returned unused drug, counts were compared to reports, and a new supply was provided (if indicated), and reported side effects. Participants received instructions to repeat use of study drug every 30 days if they experienced three consecutive days of bleeding or spotting after the first and subsequent treatments. The OHSU and UH research pharmacies maintained the computer-generated randomization scheme and treatment assignments in a locked database and assigned the intervention during the enrollment visit in a 1:1 fashion in a 2 block sequence. Study staff and participants were blinded to treatment assignments. The randomization code was broken after completion of all data collection and entry.

We used an automated daily text message service (Mir3, San Diego, CA, USA) to collect daily data on medication use and bleeding beginning on the day of enrollment. We defined bleeding as a day that required the use of protection with a pad, tampon, or liner, spotting as a day with minimal blood loss that did not require the use of any protection, and amenorrhea as a day without bleeding or spotting.9 We considered bleeding days as more burdensome to women than spotting days, so combined amenorrhea with spotting in some analyses to provide a positive indicator of no bleeding days. Research staff tracked subject diary entry every 1–2 days, and contacted the participant (phone, email and, finally, certified letter) if she failed to respond to the text messages. Research staff reviewed diary entries and prompted participants to initiate treatment if bleeding criteria were met. We considered a subject lost to follow-up after 2 weeks of no contact. The total duration of study participation was 180 days from Day 1 of first treatment. However, if a participant initiated study drug treatment within 7 days of, or on Day 180, we extended study completion by 7 days to assess response to that episode.

We used the text message bleeding diaries to collect bleeding, spotting, and amenorrhea days during participation, and had participants record paper diaries as a backup in case of missing text message responses. For missing data, we used the following rule: if bounded on both sides by no-bleeding days, we considered the day a no-bleeding day. If bounded on one or either side by a bleeding or spotting day, we coded the missing days to match the surrounding days, updating data for 9 participants. Seven of the 9 participants had data updated for only 1–2 days, one had data updated for 3 days, and one had data updated for 15 days out of the 180-day study period. Excluding participants with recoded missing data from analysis did not change the results of any primary or secondary bleeding outcomes. We used REDCap (Nashville, TN, USA) electronic data capture tool at OHSU for data management, and exported data directly from REDCap into Stata (15.1 version, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for statistical analysis.

Our primary outcome was the total number of consecutive amenorrhea days after the first treatment. Based on Simmons et al.,4 we estimated that a total sample size of 66 women (33 per group) would allow us to detect a difference of 15 days between the placebo and treatment group in the consecutive days of amenorrhea after taking the first treatment. We assumed an alpha of 0.05 with 80% power using a two-sided Student’s t-test; based on the magnitude and variance previously demonstrated (tamoxifen 28.8±24.5 days, placebo 13.6±19.2 days, pooled SD = 21.2 days). A sample size of 40 per group (N=80) was planned with a final sample size of 106 to account for drop outs.

We examined several secondary outcomes between treatment and placebo groups: (1) Kaplan-Meier estimates of days to bleeding cessation and to the restart of bleeding or spotting after the first treatment, (2) total amenorrhea, spotting, and bleeding days during the first and second 90-day reference periods, (3) total amenorrhea, spotting, and bleeding days in the 30-days after each treatment, and (4) total number of treatments and length of time (days) in between. Additional overall study outcomes included overall drop out, patient satisfaction with bleeding, side effects, and adverse effects. Adverse effects were considered drug-related if they occurred while taking the drug or following 2 weeks after treatment.

We summarized demographics and baseline clinical characteristics using descriptive statistics. We planned to evaluate the primary outcome with a two-sample t-test, as specified in the a priori analysis plan and sample size calculation. All bleeding and satisfaction outcomes were found to be significantly skewed using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Therefore, we used non-parametric methods: Kaplan-Meier estimates and a log-rank test to evaluate differences in time to bleeding cessation and time to bleeding restart, and other outcomes with the Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. We censored participants not followed for the full 30- or 90-day reference period in our Kaplan-Meier estimates, i.e. they contributed data up to the point at which they discontinued, and excluded them from the analyses of combined bleeding outcomes for that period in order to avoid estimates of bleeding outcomes that were artificially biased toward low values. Reasons for discontinuation and adverse events were reported descriptively.

Results

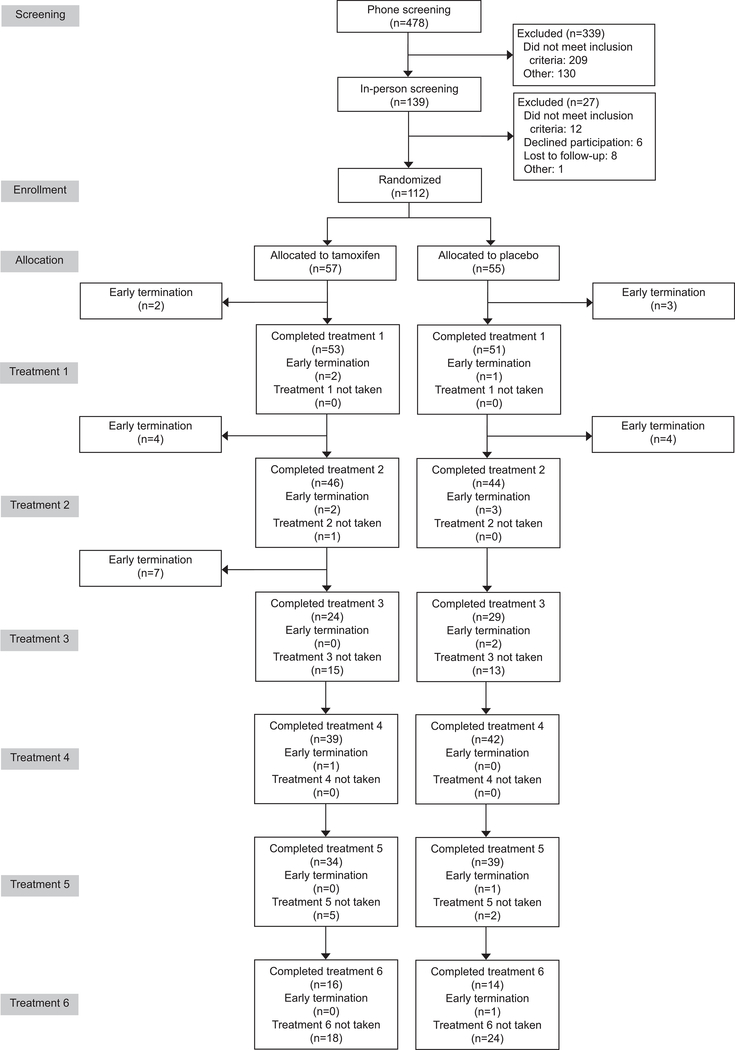

From January 2017 to November 2018, 112 women were randomized, 107 (96%) began treatment, 104 (93%) completed treatment 1, 88 (79%) completed 90 days, and 79 (71%) completed 180 days (Figure 1). The two groups had similar baseline demographics (Table 1); mean age 24, mean BMI 27 kg/m2, most identified as White not Hispanic, and the majority reported at least some college education, were nulliparous, and partnered or married. Length of implant use at study enrollment was not significantly different between treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram. The timing of treatments was dictated by each participant’s individual bleeding patterns. Consequently, the number of participants completing each treatment does not match the numbers completing each 30- or 90-day period reported in the text.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 52) | Tamoxifen (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.5 ± 5.1 | 23.4 ± 4.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 32 (61) | 30 (54) |

| Hispanic | 10 (19) | 8 (14) |

| Asian | 4 (8) | 7 (13) |

| Black | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| More than one | 4 (8) | 1 (13) |

| Other/Unspecified | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single/Divorced | 18 (35) | 13 (24) |

| Partnered/Married | 34 (65) | 42 (76) |

| Nulliparity | 46 (89) | 45 (82) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 ± 7.5 | 27.4 ± 7.4 |

| Education | ||

| High School or less | 7 (13) | 10 (18) |

| College (any or more) | 45 (87) | 45 (82) |

| Days of implant use at study entry (Range) | 469.1 ± 274.5 (42 – 1037) |

370.8 ± 267.7 (46 – 965) |

Data are mean ± SD or n(%).

After the first treatment, women randomized to tamoxifen experienced 9.8 (95% CI: 4.6–15.0) more consecutive days of amenorrhea (primary outcome) than the placebo group. Those in the tamoxifen group also experienced more total days of no bleeding (amenorrhea or spotting) in the first 90 days [median 73.5 (range 24–89) vs 68 (range 11–81), p = 0.001]. They also had a longer time to restart bleeding or spotting after their first treatment as compared to the placebo group [Kaplan-Meier median 12 days (range 1–56) vs. 6 days (range 1–38), p < 0.001, Figure 2]. Groups differed by 1 day in how fast bleeding stopped after first treatment [median 5 (range 1–21) vs. 6 (range 1–26), p=0.029]. We noted a similar increase in the number of days before return to bleeding or spotting among women randomized to the placebo group taking their first tamoxifen treatment in the open label portion of the study [Kaplan-Meier median 28 days (range 1–69), p < 0.001].

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to restart bleeding (in days) after cessation following the first study treatment in the randomized phase of the study (red and blue lines) and after the placebo group received their first active tamoxifen treatment (green line). The groups that received active tamoxifen treatment had a similar response with a prolonged period of amenorrhea as compared to placebo.

Table 2 details the secondary outcomes of overall bleeding patterns between groups during the randomized portion of the study (90-days from start of treatment 1) and the open label portion of the study (days 91–180). The tamoxifen group had more overall days of amenorrhea [median 60 days (range 18–84) vs. 52 days (range 11–67), p=0.002)], fewer days of bleeding [median 16 days (range 1–66) vs. 22 days (range 9–79), p < 0.001], but similar days of spotting [median 13 days (range 1–51) vs. 13 days (range 0–57), p=0.533)] as compared to the placebo group.

Table 2.

Comparison of the overall total number of amenorrhea, bleeding, and spotting days in the first (randomized) and second (open-label) 90-days after study treatment 1* (secondary outcomes).

| Days 1–90 Randomized | Tamoxifen | Placebo | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Range) | Median (Range) | ||

| n | 46 | 42 | |

| Amenorrhea days | 60 (18–84) | 52 (11–67) | 0.002 |

| Bleeding days | 16 (1–66) | 22 (9–79) | < 0.001 |

| Spotting days | 13 (1–51) | 13 (0–57) | 0.533 |

| Days 91–180 Open Label | |||

| n | 39 | 42 | |

| Amenorrhea days | 56 (6–81) | 67.5 (7–83) | 0.041 |

| Bleeding days | 12 (0–63) | 12 (0–82) | 0.429 |

| Spotting days | 13 (0–73) | 10 (1–42) | 0.090 |

All participants received tamoxifen during the open label phase (days 91–180).

Excludes subjects lost to follow-up before completion of reference period

Data are median (range) unless otherwise specified.

As expected, these differences between randomization groups largely disappeared during the second 90-day period of the study, as all participants were taking tamoxifen, although there is some evidence to suggest that participants taking tamoxifen for the first time experienced more amenorrhea days than those in the tamoxifen group who had been taking active treatment previously (Table 2); both groups taking tamoxifen in the open-label phase experienced more amenorrhea days [median 56 days (range 6–81) for tamoxifen group and 67.5 days (range 7–83) for placebo group] and fewer bleeding days [median 12 days (range 0–63) for tamoxifen group and 12 days (range 0–82) for placebo group] than the placebo group during the randomized portion of the study (22 days).

Participants randomized to the tamoxifen group had the opportunity to take up to 6 active tamoxifen treatments, and most (27/39, 69%) took at least 5, while participants randomized to the placebo group only had the opportunity to take up to 3 active tamoxifen treatments and the majority (38/40, 95%) took at least 2. Figure 3 details the percentage of participants taking each treatment. Time between treatments was only significantly different between treatments 1 and 2 [median 39.5 days (range 26–77) vs. 34 days (range 26–76), p = 0.027]. The results did not change when we analyzed the data by month of treatment (see Appendix 1). Over the course of the entire study, 7 participants failed to stop bleeding after taking one or more courses of tamoxifen. No significant differences were identified between the demographic and clinical profiles of those who responded to treatment and those who did not. When combined with participants who were lost to follow-up, those who did not respond to treatment/did not complete the study were younger and had their implant in place for a shorter period than those who responded to treatments and completed the study (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Percentage of participants that took each treatment, with total number in each group at the beginning of each treatment (at top of bar). All participants had to experience 3 days of bleeding or spotting at the beginning of the study within 30 days of enrollment; otherwise, they were withdrawn. Study drug could be taken no sooner than every 30 days and up to a total of 3 times in each 90-day treatment period or a maximum of 6 total treatments over the entire study. All participants received tamoxifen treatment in the second 90-day period.

Women remained consistently satisfied with their implant ‘for contraception’ over the entire course of the study (Table 3). Satisfaction and acceptability of bleeding patterns was low and no different between treatment groups at baseline, markedly improved during the randomized portion of the study, with significantly higher satisfaction levels in the tamoxifen group compared to placebo after the initial treatment [median 71 (range 8.5–100); 31 (range 0–100), p < 0.001] and at the end of the first 90-day reference interval [median 62 (range 16–100), 46 (range 0–100), p = 0.023]. After completion of the open label phase of the study, satisfaction with bleeding in the treatment groups were not significantly different [median 67.5 (range 0–100), 54.25 (range 0.5–98), p = 0.129]. Results for acceptability of bleeding followed similar trends with no significant differences between treatment groups.

Table 3:

Satisfaction with bleeding and implant as contraception, and acceptability of bleeding, assessed by visual analog scale (VAS), and compared using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test.

| Tamoxifen | Placebo | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Outcome | n | Median (Range) | n | Median (Range) | |

| Baseline | Satisfaction w/ bleeding | 55 | 18 (0–76) | 52 | 13.75 (0–57.5) | 0.160 |

| Satisfaction w/implant | 87 (26–100) | 80.5 (30–100) | 0.933 | |||

| Acceptability of bleeding | 16 (0–66) | 14.5 (0–83.5) | 0.667 | |||

| After first treatment | Satisfaction w/ bleeding | 52 | 71 (8.5–100) | 49 | 31 (0–100) | < 0.001 |

| Satisfaction w/implant | 83 (27–99) | 80 (0–100) | 0.852 | |||

| Acceptability of bleeding | 71 (16–100) | 32 (0–100) | < 0.001 | |||

| At end of first 90-days (end of RCT) | Satisfaction w/ bleeding | 45 | 62 (16–100) | 44 | 46 (0–100) | 0.023 |

| Satisfaction w/implant | 83 (16–100) | 80.5 (15–100) | 0.369 | |||

| Acceptability of bleeding | 64 (8–100) | 45.25 (0–100) | 0.007 | |||

| At end of 180-days (end of open label) | Satisfaction w/ bleeding | 38 | 67.5 (0–100) | 40 | 54.25 (0.5–98) | 0.129 |

| Satisfaction w/implant | 81 (17–100) | 81.75 (19–100) | 0.767 | |||

| Acceptability of bleeding | 66.5 (0–100) | 52.25 (0–90) | 0.078 | |||

| End of study (early termination participants) | Satisfaction w/ bleeding | 8 | 38.75 (6–99.5) | 6 | 12.5 (1–73) | 0.175 |

| Satisfaction w/implant | 70 (53–100) | 80.5 (45–100) | 0.667 | |||

| Acceptability of bleeding | 28 (8–99) | 17 (1–67) | 0.199 | |||

Over the course of the study, 28 participants discontinued (Table 4). Eight withdrew because they chose to have their implant removed (3 from the tamoxifen group and 5 from the placebo group). Four participants, all from the tamoxifen group, discontinued because they were dissatisfied with the study drug either because it was not helping (1), their bleeding improved (1), side effects (1; mood changes), or wanted to try something different (1). Equal numbers found the study too difficult (1 from each group) or cited “other” (6 from each group) as their reason for withdrawal, and 2 participants (both from the tamoxifen group) did not provide a reason for discontinuation. Few participants reported treatment-related adverse events (Table 5) and no serious adverse events occurred during the study. More women taking tamoxifen reported fluid retention (12 vs. 1), headache (19 vs. 1), and mood changes (13 vs. 2).

Table 4: Reasons for Withdrawal From the Study.

Data are n(%).

| Reason for withdrawal | Tamoxifen (n = 57) | Placebo (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|

| Implant removal: irregular or frequent bleeding | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Implant removal: heavy bleeding | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Implant removal: desiring pregnancy | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Implant removal: other | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Dissatisfaction with study drug: not helping | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Dissatisfaction with study drug: wants to try another drug with primary MD | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Dissatisfaction with study drug: side effects | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Dissatisfaction with study drug: don’t need it/bleeding improved | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Study visits too difficult | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 6 (11) | 6 (11) |

| No reason recorded | 4 (7) | 3 (5) |

Table 5.

Incidence of Adverse Events in the Study

| Adverse Event | Tamoxifen (n = 55) | Placebo during Randomized (receiving Placebo; n = 52) | Placebo during Open Label (receiving Tamoxifen; n = 42) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Cramping/changes in menstrual fluid | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Fluid retention | 10 (18) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Headache/migraine | 16 (29) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) |

| Hot flashes | 6 (11) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Mood changes | 11 (20) | 2 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (9) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Rash | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Vision flashes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weakness/fatigue/dizziness | 6 (11) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Weight loss | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Yeast infection/BV | 5 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data are n(%).

Discussion

We found that etonogestrel implant users with frequent or prolonged unscheduled bleeding benefitted from a seven-day treatment course of tamoxifen. Women taking tamoxifen experienced a prolonged reprieve from bleeding with more total consecutive days of amenorrhea after one treatment as well as more overall days of amenorrhea, and fewer days of bleeding in a 90-day time reference period. During the open label phase, those women randomized to placebo who received active treatment with tamoxifen showed a similar level of improvement. Women randomized to tamoxifen during the initial phase also reported higher satisfaction and a higher level of acceptability of their bleeding patterns with tamoxifen treatment. During the open label phase, satisfaction with bleeding improved in the placebo group after these women commenced active tamoxifen treatment. Taken together, these results support a positive benefit of short (7 day), repeated (woman-controlled, but no more frequent than every 30 day) courses of tamoxifen as a strategy to improve bleeding patterns during use of the etonogestrel implant.

Other treatments like oral contraceptive pills also decrease or stop bleeding while on treatment, but shortly after stopping, unscheduled bleeding restarts.7 Similar to these approaches, our data support that tamoxifen does not permanently prevent breakthrough bleeding. Therefore, tamoxifen provides a “treatment” but not a “cure” for breakthrough bleeding. Unlike oral contraceptives, women using a short course of tamoxifen experience a prolonged interval before their bleeding returns. We did not demonstrate a convincing benefit with repeated treatments. However, our relatively short period of study may have prevented our ability to observe this effect. Bleeding patterns with contraceptive implants change unpredictably, and up to 50% of women with unfavorable patterns who continue use will find an improvement over time.10 This variability likely diluted our ability to show a difference with repeated dosing.

Treatment with tamoxifen resulted in an increase in the number of days of amenorrhea. During the randomized phase of the trial, women who received active treatment experienced about 10 more days of amenorrhea in the first 30 days and 8 more days of amenorrhea over 90 days. While this difference is not as large as the 15.2 days that our study was powered to detect, our larger sample size and lower variability enabled our smaller difference to be statistically significant and we believe they represent a meaningful improvement in bleeding patterns. Notably, this improvement resulted from less bleeding days as the number of spotting days did not change with treatment. Spotting episodes represent a lower burden for women than bleeding, as these events do not require sanitary protection. Women using tamoxifen had a similar number of bleeding days to that expected with normal spontaneous menses (median 7–15 days in 90 days).11 Thus, most women using tamoxifen should experience a reduction of bothersome bleeding with treatment.

Breakthrough bleeding during the use of contraceptive implants likely occurs as a result of abnormal blood vessel development. New blood vessel development occurs in the endometrium during natural cycles, and serves to support pregnancy. This neovascularization occurs primarily during the proliferative phase under estrogen regulation.12 Constant exposure to contraceptive concentrations of a progestogen downregulates estrogen and progesterone receptors in the endometrium.13 Two types of estrogen receptor exist, ERα and ERβ. Most of the effects of estrogens in the reproductive tract are mediated by ERα, but the endothelial cells of the endometrium express only ERβ.14 Tamoxifen appears to inhibit endometrial angiogenesis by increasing the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1.15 Tamoxifen is an antagonist for estrogen receptor beta but a partial agonist for estrogen receptor alpha.16,17

Tamoxifen treatment did not improve bleeding patterns in all women in our study. Progestin-induced bleeding results from multiple factors including inflammatory, coagulation, and angiogenesis components, so one type of treatment will likely not work for everyone.16

Strengths of our study include the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design and adequate sample size to address our primary outcome. We had excellent retention through the randomized phase of the study. We used a text messaging service to provide daily information on bleeding events and decisions to initiate a new course of treatment, and backed this up with active tracking and phone contact by research staff. We chose to have all participants move into an active “open label” treatment phase for the second three month phase of the study rather than switch allocations in a crossover design. While a crossover design provides a powerful approach to assess response to treatment with each participant serving as her own control, we did not know how long the benefit of one or more active treatments with tamoxifen might last. As we hypothesized that tamoxifen treatments would have a carryover effect, a crossover design may have diluted our ability to demonstrate a difference in the second three months. We also felt that the opportunity for all participants to receive an active treatment after 90 days would reduce drop out.

Weaknesses include generalizability, as we had few participants at the Oregon or Hawaii study sites who identified as black. Our participants also agreed to take part in a randomized trial and therefore, may not reflect the general population of implant users who present for discontinuation due to bleeding problems. We also enrolled women as early as 42 days after initiation of implant use, with duration of implant use under three months in nine women. Since bleeding patterns in the first 90 days do not predict later bleeding10, some of these women would likely experience better (or worse) bleeding irrespective of treatment, potentially diluting or ability to observe an effect. We did not extensively rule out other sources for the bleeding, other than testing for the presence of chlamydia, as the likelihood of a structural abnormality in this reproductive age population would be rare. We expected and prepared for a higher dropout rate than typically seen with clinical trials based on prior experience with a population of implant users with bothersome bleeding. Our apriori increase in sample size enabled us to have a sufficient sample size at the end of 90 days to analyze our primary outcome. Overall, our population of ‘discontinuers’ appear to be no different than those that continued. Although dropout was anticipated, attrition was 21% at 90 days and 29% by study completion which may have resulted in a biased sample limiting the interpretation of the results.

One of our greatest challenges with recruitment was the concern expressed by some potential participants and other clinicians about using a ‘cancer drug’. Risks of tamoxifen treatment with long-term continuous use include venous thromboembolism, similar to other estrogens. However, our results and other studies using short courses of tamoxifen have shown no serious adverse events and high acceptability. A prior study from our group documented that a 7-day course of tamoxifen does not interfere with the contraceptive effect of the implant.4

In summary, a seven-day treatment course of tamoxifen appears to temporarily stop troublesome bleeding in etonogestrel implant users. Our data support the use of tamoxifen as an effective option that offers the benefit of a shorter duration of treatment than other approaches such as combined oral contraceptives. While we could not confirm a statistically significant benefit with additional treatment courses in our short study, we did observe a clinically important reduction in the number of bleeding days (6) and an increase in the number of amenorrhea days (8) during the randomized study that persisted during the next 90 days. Women who began treatment during the open label phase showed a similar improvement. Our participants used tamoxifen in repeated doses throughout the study; the majority used the medication regularly. This approach appeared safe and well tolerated and offers a woman-controlled strategy to manage unpredictable bleeding with the etonogestrel implant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the OHSU’s Women’s Health Research Unit and University of Hawaii Women’s Health Research Center, particularly Tiana Fontanilla and Janela Agonoy for the work and support given to this project.

Financial Disclosure: Alison B. Edelman is a consultant for World Health Organization, CDC, Gynuity Health Projects, FHI360, and Exeltis. She is a Nexplanon trainer for Merck but has declined all honorariums since 2016. She is an author for UptoDate (Royalties received). Her institution receives research monies from Merck, HRA Pharma, and NIH on projects where she is principal investigator. Dr. Jensen has received payments for consulting from Abbvie, Cooper Surgical, Bayer Healthcare, Merck, Sebela, and TherapeuticsMD. OHSU has received research support from Abbvie, Bayer Healthcare, Daré, Estetra SPRL, Medicines360, Merck, and Sebela. These companies and organizations may have a commercial or financial interest in the results of this research and technology. These potential conflicts of interest for A. Edelman and J. Jensen have been reviewed and managed by OHSU. Bliss Kaneshiro’s institution receives research monies from Sebela, Gynuity Health Projects, and the National Institutes of Health on projects where she is a principal investigator. Katharine B. Simmons is a Nexplanon trainer for Merck. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Financial Source: Grant support for this research was from a Merck Women’s Health Investigator Initiated Studies Program (PI Edelman) and the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (1 UL1 35RR024140 01) for access and use of REDCap electronic data capture system.

Footnotes

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apter D, Briggs P, Tuppurainen M, et al. A 12-month multicenter, randomized study comparing the levonorgestrel intrauterine system with the etonogestrel subdermal implant. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(1):151–157.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC - Implants - US SPR - Reproductive Health. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/spr/implants.html. Published January 16, 2019 Accessed March 18, 2020.

- 4.Simmons KB, Edelman AB, Fu R, Jensen JT. Tamoxifen for the treatment of breakthrough bleeding with the etonogestrel implant: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2017;95(2):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Aleem H, Shaaban OM, Amin AF, Abdel-Aleem AM. Tamoxifen treatment of bleeding irregularities associated with Norplant use. Contraception. 2005;72(6):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou MY, McNicholas C, Creinin MD. Combined oral contraceptive treatment for bleeding complaints with the etonogestrel contraceptive implant: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care Off J Eur Soc Contracept. 2016;21(5):361–366. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2016.1210122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guiahi M, McBride M, Sheeder J, Teal S. Short-Term Treatment of Bothersome Bleeding for Etonogestrel Implant Users Using a 14-Day Oral Contraceptive Pill Regimen: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):508–513. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDA. FDA Prescribing Information, Nexplanon. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021529s011lbl.pdf. Accessed January 17,2020.

- 9.Mishell DR, Guillebaud J, Westhoff C, et al. Recommendations for standardization of data collection and analysis of bleeding in combined hormone contraceptive trials. Contraception. 2007;75(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care Off J Eur Soc Contracept. 2008;13 Suppl 1:13–28. doi: 10.1080/13625180801959931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Broder MS, Fraser IS, FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada H, Tsutsumi A, Imai M, Nakajima T, Yasuda K, Kanzaki H. Estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators regulate vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 in human endometrial stromal cells. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(8):2680–2686. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slayden OD, Brenner RM. Hormonal regulation and localization of estrogen, progestin and androgen receptors in the endometrium of nonhuman primates: effects of progesterone receptor antagonists. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67(5):393–409. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Critchley HO, Brenner RM, Henderson TA, et al. Estrogen receptor beta, but not estrogen receptor alpha, is present in the vascular endothelium of the human and nonhuman primate endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(3):1370–1378. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmestam M, Andersson H, Stavreus-Evers A, Brittebo E, Olovsson M. Tamoxifen modulates cell migration and expression of angiogenesis-related genes in human endometrial endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(6):2527–2535. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grow DR, Reece MT. The role of selective oestrogen receptor modulators in the treatment of endometrial bleeding in women using long-acting progestin contraception. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2000;15 Suppl 3:30–38. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_3.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkhem T, Carlsson B, Nilsson Y, Enmark E, Gustafsson J, Nilsson S. Differential response of estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta to partial estrogen agonists/antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54(1):105–112. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.