Abstract

Background

The 1994 genocide against Tutsi resulted in a massive death toll that reached one million people. Despite the tremendous efforts made to mitigate the adverse effects of the genocide, a substantial burden of mental health disorders still exists including the notably high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among genocide survivors. However, a synthesized model of PTSD vulnerability in this population is currently lacking.

Methods

A meta-analysis of 19 original research studies that reported PTSD prevalence (n= 12,610). Medline-PubMed and Science.gov were key search engines. Random-Effects Model (k = 19; taû2 estimator: DL) was applied. Data extraction, synthesis, and meta-analysis were carried out using R.

Results

The total of 2957 out of 11746 individuals suffered from PTSD. The summary proportion is 25 % (95% CI=0.16,0.36). The taû2 is 0.06 (95% CI=0.03,0.14) in the absence of subgroups, and the Q-statistic is 2827.65 (p<0.0001), all of which suggests high heterogeneity in the effect sizes. Year of data collection and Year of publication were significant moderators. PTSD pooled prevalence in the genocide survivor category was estimated at 37% (95% CI=0.21,0.56).

Conclusion

The PTSD prevalence among genocide survivors is considerably higher compared to the general Rwandan population. The burden of PTSD in the general Rwandan population declined significantly over time, likely due to treatment of symptoms through strong national mental health programs, peace building and resolution of symptoms over time. To the best of our knowledge little evidence has reported the burden of PTSD prevalence in African post conflict zones particularly in Rwanda.

Limitation:

Limitations of our review include the use of retrospective studies and studies with very small sample sizes, as well as language criterion.

Keywords: PTSD, Prevalence, Biological mechanisms, Genocide, Rwanda

1. Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is defined as a mental illness that people develop after experiencing a life-threatening event, like combat, a natural disaster, a car accident, or sexual assault.1 PTSD is mainly characterized by flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance, numbing and hyper-vigilance.2 It originates from the maladaptive persistence of appropriate and adaptive responses, which occur during traumatic stress, and therefore a variety of reactions may be observed after major trauma. Global estimates of the lifetime prevalence of PTSD have been shown to vary considerably between countries and estimates of lifetime worldwide prevalence of PTSD range from 3% to 14%.3 Data collection for a recent study on the size and burden of mental disorders in Europe revealed differences in PTSD prevalence that ranged from 0.56% to 6.67% in the general population.4 The countries with the highest prevalence of PTSD were the Netherlands, the UK, France and Germany and the countries with the lowest prevalence of PTSD were Spain and Switzerland.4 In Sub-Saharan African Countries, one study conducted in Uganda has shown that the prevalence of PTSD was 11.8% (95% CI: 10.5%, 13.1%)5, suggesting that different factors were strongly associated with PTSD.6 In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the rate of PTSD is 44% in certain subpopulations due to ongoing conflict in the region.7

Epidemiological studies have helped to understand the progression of PTSD in different populations especially those in post conflict zones like Rwanda. However, the prevalence of the disease is likely to diverge due to different factors including the diagnostic methods, population characteristics as well as the nature of traumatic events encountered.8,9 For example, the 1994 genocide against ethnic Tutsi resulted in a substantial burden of mental health disorders including PTSD in the Rwandan population, especially among genocide survivors. According to Munyandamutsa and colleagues10, the estimated prevalence of PTSD among Rwandan population was around 26.1%10. However, substantial heterogeneity exists in the prevalence of PTSD reported in Rwandan post-genocide. For example, the estimated prevalence of PTSD among Rwandese refugees residing in Nakivale refugee settlement in South Western Uganda was 22%.11 In contrast, the prevalence of PTSD among Rwanda defense force and military personnel was rated at 4.2%.12 Moreover, Schal and colleagues compared rates of mental health disorders in Rwandan genocide perpetrators with those of genocide survivors and found that diagnostic criteria for PTSD was met significantly more frequently among genocide survivors than perpetrators (46% vs 14%13). In the National Trauma Survey conducted one year after the genocide,14 probable PTSD was reported at 62% and 54% in two separate samples of Rwandans aged 8–19 years old14.

The conflicting estimates of PTSD prevalence across these and multiple other published studies focused specifically on post-genocide Rwanda suggests the need for development of a synthesized model that more precisely captures the overall estimate and potential sources of heterogeneity, in order to identify important differences that are relevant to changing patterns in population health. However, a synthesized model of PTSD vulnerability in this population is currently lacking. Such a model is of critical importance to direct proper clinical decision and inform public health approaches to prevent, mitigate and manage PTSD and other associated neuropsychiatric disorders in Rwanda. To address this gap, here we synthesize and evaluate existing evidence regarding the pooled prevalence of PTSD in post genocide population.

2. Method

In this meta-analysis study, PTSD was defined as a mental health disorder that is characterized by flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance, numbing and hyper-vigilance.15 The inclusion criteria are based on Joanna Briggs Institute Method for Systematic Review16: studies that reported PTSD prevalence or PTSD in Rwandan population of 14 years of age and above. In addition, the review considered studies that reported prevalence in both males and females. The review considered both analytical observational studies; prospective, retrospective, and cohort studies; descriptive studies including case series, individual case reports and case-control studies. The first item of interest was the pooled prevalence of PTSD and the second item of interest was heterogeneity factors that influence differences in the prevalence of PTSD in Rwandan population as reported in the literature. Most reviewed studies have used questionnaires assessing PTSD symptoms such as Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, PCL-M, SPDS, 17 Item, PCL, PSS. However, a number of studies have been able to to apply disgnostic instrument such as DSM5, DSM4, MINI, and TMLPC Breslau’ seven Item screener.20,21,22,23,24

2.1. Search Strategy PubMed/Medline (2004-April/2018)

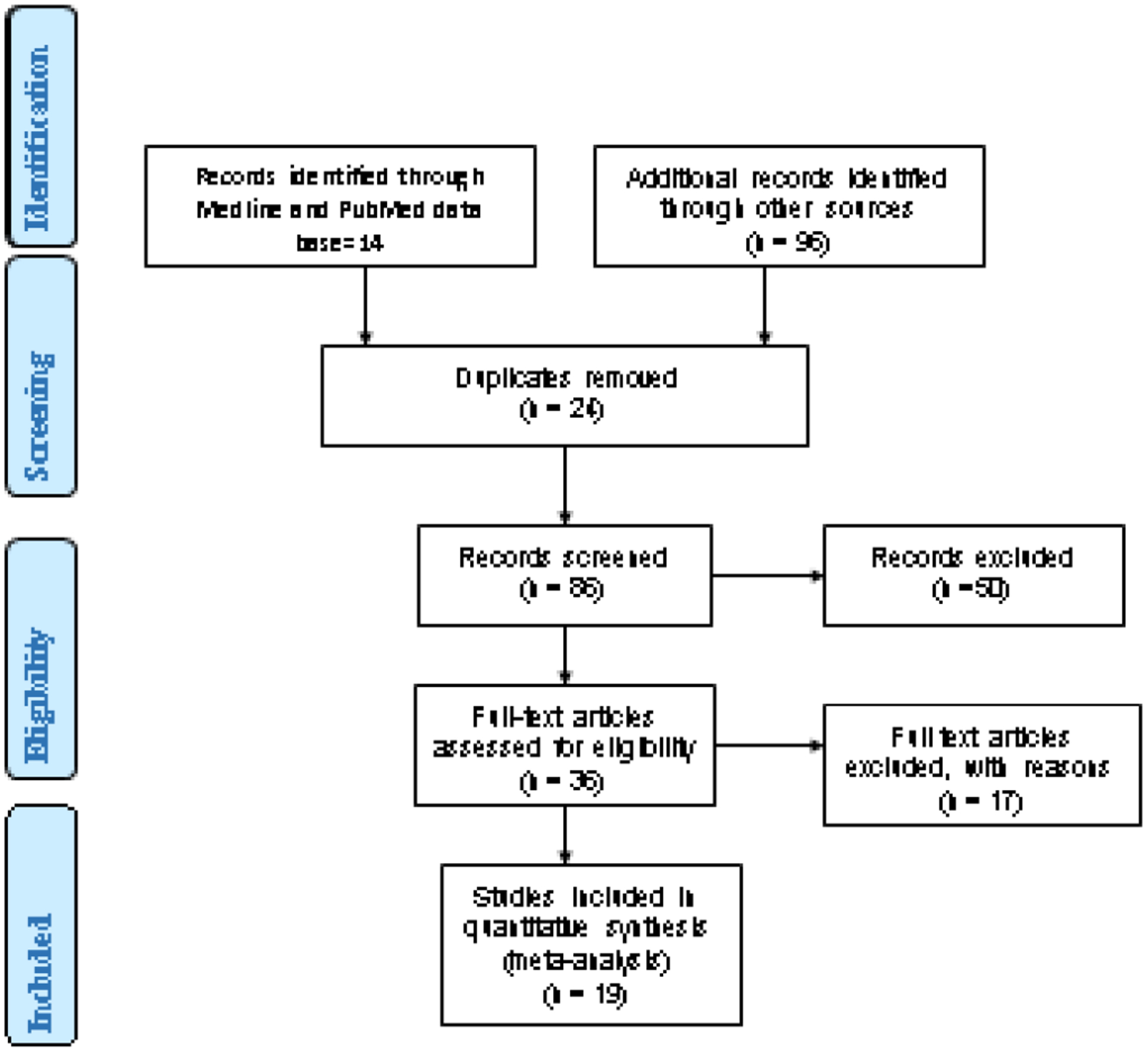

To identify articles to be included in the meta-analysis we applied the following search terms: ((((((“Stress Disorders, Post- Traumatic”[Mesh]) OR Traumatic stress [Title/Abstract]) OR PTSD[Title/Abstract]) OR posttraumatic stress disorder[Title/Abstract])) AND (((prevalence[Title/Abstract]) OR epidemiology[Title/Abstract]) OR morbidity[Title/Abstract])) AND Rwanda[Title/Abstract]. Methodological quality of articles for the meta-analysis was assessed by identifying citations, which were ordered and uploaded into Mendeley after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts were then screened by two independent reviewers (LM, AU) for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review and meta-nalysis as highlighted above were recovered in full. The full text of the selected studies was retrieved and assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria (studies reported that reported prevalence on Rwanda population of Age group 14 years above, both female and male, published in English language). Full text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria as highlighted above were excluded and reasons for exclusion were provided in appendix. The results of the search were reported in full in the final report and presented in PRISMA flow diagram (Figure1). Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer. During methodological assessment, decisions to exclude articles were based on decision rules including exposure, context, population, comparator and outcomes. The selected studies were critically appraised by two independent reviewers at the study level for methodological quality in the review using standardized critical appraisal instruments from the Joanna Briggs Institute through SUMARI. Any disagreements that arise were resolved through discussion, or with a third reviewer (ER).

Fig. 1:

Prisma Flow Diagram.

2.2. Data extraction

Data extraction from papers was performed using the standardized data extraction tool for prevalence and incidence available in JBI tools by independent reviewers. For the risk factors component of the review, the standardized data extraction tool for reviews of risk factors available in JBI guidelines was used. The data extracted were included with specific details about the condition, populations, study methods and proportions of interest to the review question and specific objectives. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were fixed through discussion or with a third reviewer. Authors of papers were contacted to request missing or additional data where required.

2.3. Quality assessment

The quality of evidence was assessed by considering following information where appropriate: context of the study, condition (diseases), population and proportion estimates, and the sample size. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by considering the sample size in each study, as well as groups included within the “other specific population” category (see below). Studies that targeted a population other than Rwandans were excluded in the calculation of pooled prevalence of PTSD.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The normality test for PTSD proportion was performed to decide if logit transformation or raw proportions were appropriate statistical effect sizes to be considered in the meta-analysis. Shapiro-wilk test was used to test the variability among the PTSD proportion of the studies included in the review at the p-value (<0.05). We rejected the null hypothesis, which suggested the evidence of lack of normality and hence the log transformation was statistically appropriate for meta-analysis.17 Papers were included in the statistical meta-analysis when it reported the prevalence or incidence of PTSD in Rwandan population and the year of publication was between 2004 and 2018. Effect sizes were expressed as proportion within 95% confidence intervals around the summary estimate. Heterogeneity was statistically assessed using the standard chi-square, Tau2 and I2 tests. A subgroup analysis was done by age category (<30 years & >30 years old) hypothesizing that the PTSD pooled estimate may be higher in adults than in children.The last subgroup analysis was done by target population category (PTSD prevalence in population surveys category, PTSD prevalence in genocide survivors category and PTSD prevalence in other specific population categories such as prisoners, refugees and military). Further analysis has been done by omitting studies on the military group in order to test if the military group is an influential factor driving the lower observed pooled prevalence in “other specific population” category.

Meta-regression analysis was performed for studies that had enough metadata such as year of data collection, sample frame, and age group to investigate significant heterogeneity factors. To identify influential and outlying studies, a summary proportion leaving out each study was calculated using R software. Meta-regression analysis was performed where possible depending on the available metadata (Mean age, year of publication, sample size and year of data collection) to assess moderating effects of heterogeneity between studies as well as effect size estimate. A summary of findings was presented in tables or figures created using R or JBI SUMARI software.18,19

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

The review yielded 19 studies out of 110 articles (Fig.1). The total sample size of the 19 included studies was 11,746 subjects (i.e. 6021 females and 5725 males). The total number of individuals suffering from PTSD was estimated at 2957. Most of the studies were conducted at a population-based level. The diagnosis of PTSD was carried out using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, PCL-M, SPDS, 17 Item, PCL, PSS, DSM5, DSM4, MINI, and TMLPC Breslau’ seven Item screener.20,21,22,23,24

3.2. Meta-analysis results of PTSD prevalence estimates

3.2.1. Effect Size Estimation

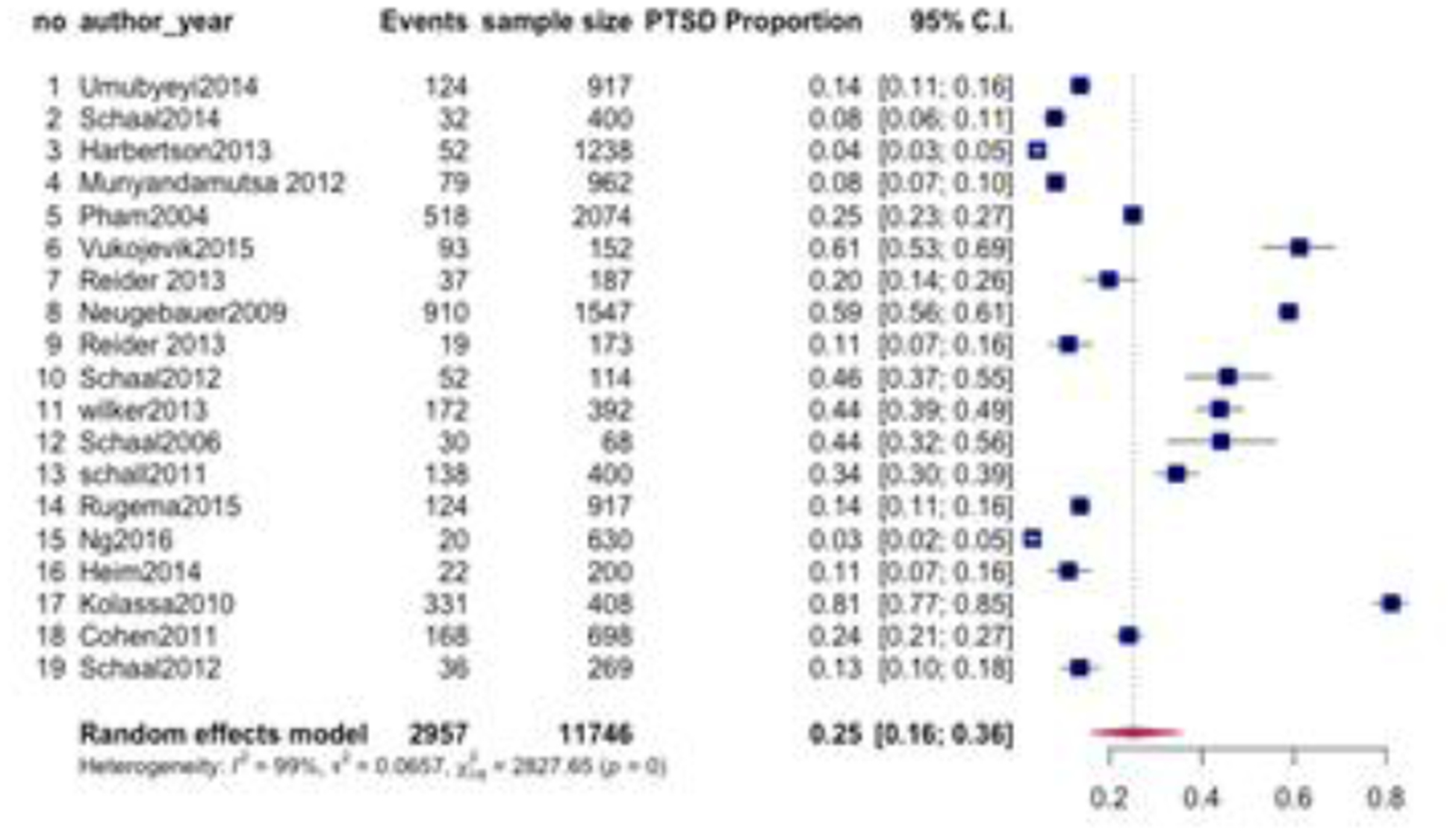

The summary proportion of PTSD prevalence was 25% (95% C.I. =0.16, 0.36); yet the tau-2 was 0.0656 (95% C.I. =0.03, 0.14) and I2 99.5%, both of which suggest high heterogeneity in the effect size (Fig. 2). The visual inspection of the forest plot identified several potentially outlying studies including Vukojevik (2015), Kolassa (2010), Haberston (2013) and Neugebauer (2008)25,26,12,14 (Fig. 2). There was a slight difference in PTSD prevalence by age group where it was estimated at 26% in the age group of ≤30 years old and 27% in the age group of above 30 years old. The pooled prevalence by sample frame was done in three categories (PTSD prevalence in population surveys category, PTSD prevalence in genocide survivors’ category and PTSD prevalence in other specific population categories such as prisoners and refugees) the prevalence was estimated at 15% (95% C.I. =0.02, 0.35), 37% (95% C.I. =0.21,0.49), 12% (95% C.I.=0.00,0.26), respectively with I2 99% of overall heterogeneity among studies. The pooled prevalence among the third category that lumped refuges and prisoners increased from 12% to 24% (95% C.I.=0.11,0.41) after omitting studies on the military group and this confirmed that the military group is an influential factor driving the lower observed pooled prevalence rates when the military group is included in the “other specific population” category.

Fig. 2:

Pooled prevalence of PTSD by studies published in the period (2004–2018).

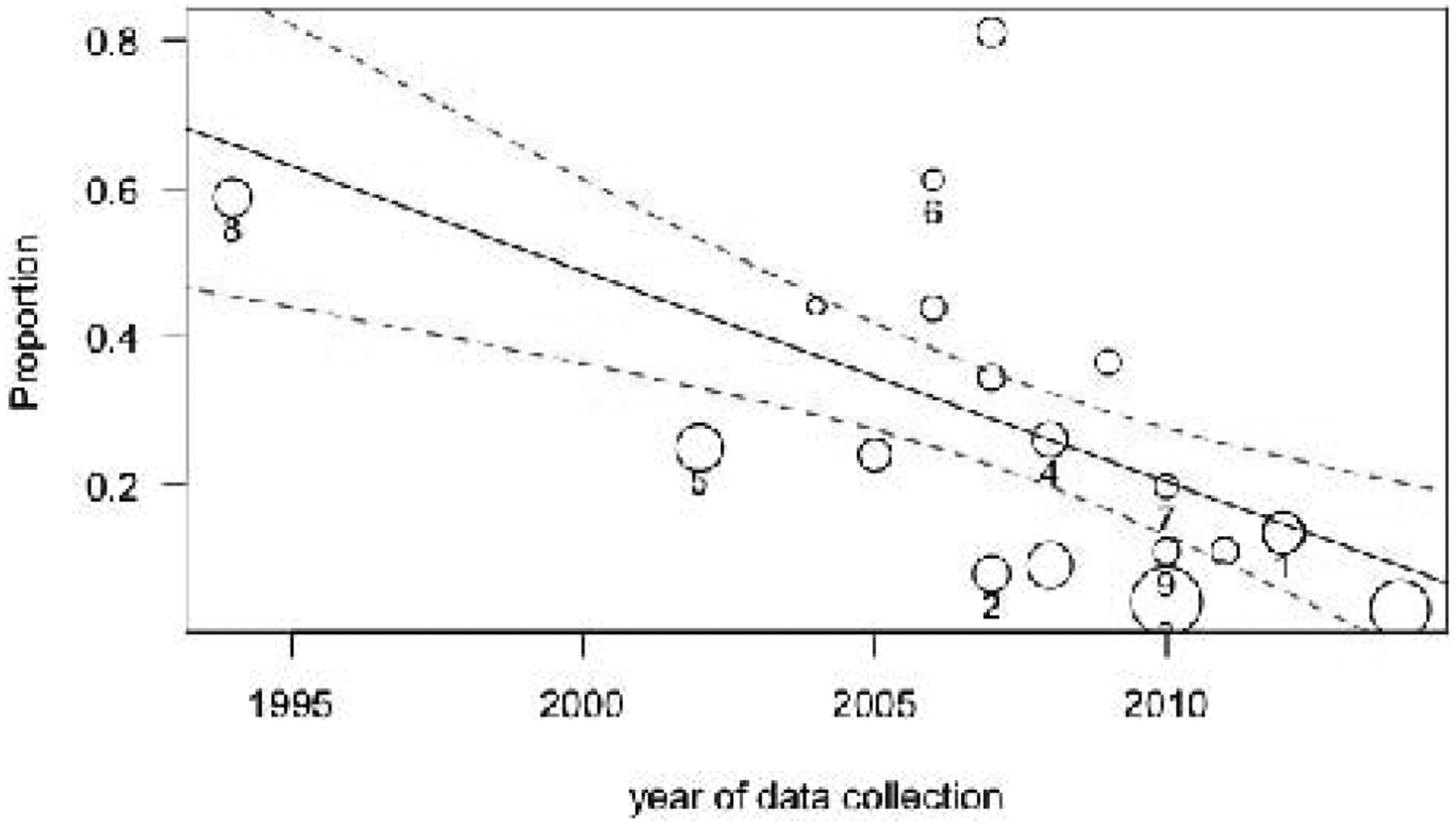

3.2.2. Meta-regression analysis

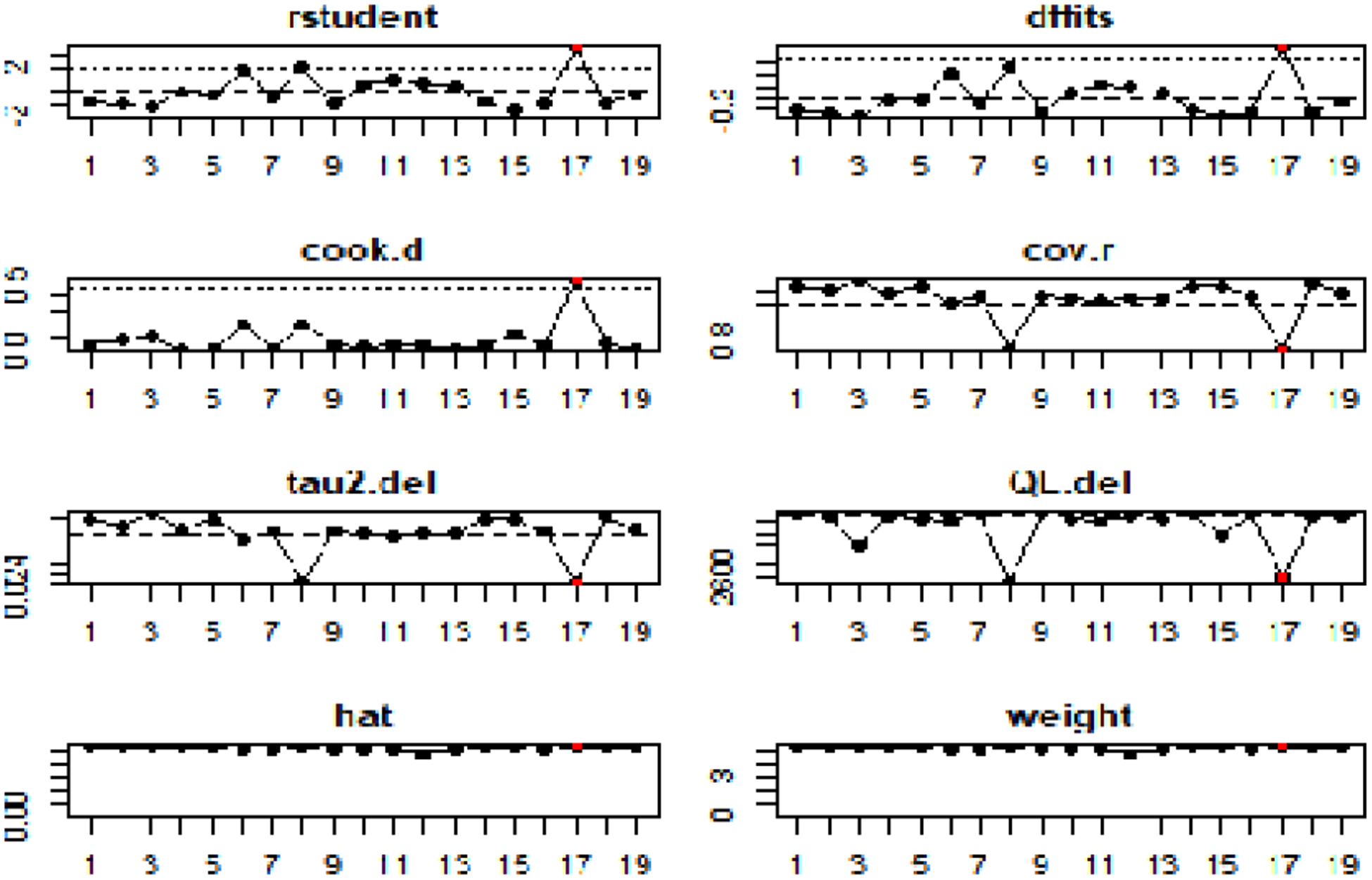

As substantial heterogeneity remained after exclusion of potential outliers, we explored potential moderators including age, year of data collection, year of publication and sampling frame. A visual inspection of the scatter plot revealed that the year of data collection was negatively correlated with the observed proportions and the test of moderators was (QM (1) =44%, p<0.001). The significant slope coefficient was (0.0008; p<0.001) confirming the significant association between the year of data collection and the observed effect sizes (Figure 3). Furthermore, the R2 for year of data collection indicated that year of data collection accounted for 39% of the true heterogeneity in the observed effect size. According to the visual inspection of scatter plot for year of publication, we found that the slope of estimated regression line was steeper and the results revealed that the year of publication was significantly associated with the observed effect sizes (QM (1) =3.54, p=0.0165) which was supported by the significant regression coefficient (0.0300 p=0.0165). In addition, the R2 showed the 8% of the true heterogeneity in the observed effect size was explained by year of publication with earlier studies (i.e. studies published closer in time to the genocide) showing a strong positive association with higher PTSD prevalence (p=0.01). Age was not a significant moderator (QM (1) =0.395, p=0.52), as indicated by the non-significant regression coefficient (−0.0045 p-value=0.52) and R2 of 4% in accounting for the true heterogeneity in the observed effect size. In addition, the sampling frame was not a significant moderator (QM (1) = 29, p=0.58), which is also supported by the non-significant regression coefficient (0.5650, p>0.05). Multiple regression analysis was conducted by combining significant moderators (i.e. year of data collection and year of publication) and the finding revealed that only year of assessment was significant (p<: 0.009) in the presence of year of publication. 17th i.e. Kolassa et al., 2011 was identified as a suspect influential and outlying study (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3:

Year of data collection accounted for 39% of heterogeneity in the observed effect sizes (p=0.0008).

Fig. 4.

Externally standardized residuals, DIFFITS values, Cook’s distances covariance ratios, estimates of τ2 and test statistics for (residual) heterogeneity when each study is removed in turn, that values, and weights for the 19 studies evaluating the prevalence of PTSD in Rwandan population .The 17th study highlighted in red is suspected as an outlier that may have contributed to high heterogeneity at the cut off 2.

3.3. Publication Bias

We evaluated the possibility of publication bias through funnel plots by log odds which provides evidence of asymmetry. Because the ties were due to identical values in the dataset, the ranks are not unique and hence exact p-values could not be calculated and therefore, only Eager’s regression test with the unweighted regression test could be applied to confirm the asymmetry status. The Eager’s regression test showed that the funnel plot is significantly asymmetrical with p-value =0.0098, providing supporting evidence of publication bias.

4. Discussion

The present meta-analysis revealed an overall prevalence of PTSD estimated at 25% among individuals sampled in post-genocide Rwanda. Our findings were in agreement with data from a 2012 study conducted by Munyandamutsa and colleagues10 which reported the prevalence of 26% among the general Rwandan population. However, our results from the PTSD by subgroup analysis showed a higher prevalence in the genocide survivors’ group (37%) compared to the “other specific population” category (24% when considering only prisoners and refugees), and to the general population (15%).

Our findings are comparable with the recent Rwanda Mental Health Report (RMHR) findings which also revealed a high prevalence of PTSD among genocide survivors (28%).27 In general our findings are comparable with the PTSD prevalence rates in other post conflict zone such as Algeria (37.4%), Cambodia (28.4%), Ethiopia (15.8%) and Gaza (17.8%), Bosnia (PTSD prevalence ranged from 11% to 36%).28,29 The PTSD prevalence rates in our review are lower compared to the PTSD prevalence in holocaust population ranging between 35%–65% although we share similar histories.30,31 Most of the studies in recent years may have been focusing on the genocide survivors and therefore this may have contributed to the increase of pooled prevalence generated by our review. On the other hand, the pooled proportion of estimated PTSD prevalence (37%) in the survivor’s category by subgroup analysis is equal to the prevalence of PTSD among genocide survivors (37%) reported by RMHS of 2018 within Kigali City.

The differences observed in PTSD prevalence may be explained by the high heterogeneity among the studies included in the review. Our findings are also in agreement with data from the 2002 survey by Pham and collaborators who reported the prevalence of PTSD 19.6% among men and 29.7% women, respectively.32 The burden of PTSD significantly declined over time and this decline of PTSD prevalence was mainly due to treatment of symptoms, resolution of symptoms due to time, national efforts in peace building, trauma healing programs, strong national mental health program and a remarkable change in the economic development of the country which may have built resilience to trauma and PTSD in the population and hence positively impacted mental health.10, 33,34Other explanations may be due to the type of targeted population as well as sampling techniques and tools utilized by different studies. The findings about the PTSD prevalence among military personnel have been reported to be very low compared to other groups. The data confirm that the the pooled prevalence among the third category named “other specific population” lumped refuges and prisoners and the PTSD prevalence increased from 12% to 24% after dropping studies on the military group”.Therefore, the military group is significantly considered as an influential factor driving the lower observed pooled prevalence rates in the other specific population category. This may be explained by mainy reasons including accessibility to the training and resilience.35,34,36 In addition, results from this analysis demonstrate that only year of assessment was significant in the presence of year of publication. The Year of assessment means the year of data collection related to the symptoms of PTSD in post genocide Rwandan population. The range of year of assessment reported by studies included in our review is between 1994–2014. Although year of publication showed some main effects, only year of assessment was significant in meta-regression models that included year of publication because some studies took a long time to publish and hence resulted in publication bias

The strengths of this review include the use of studies published between 2004–2018, which provided the prevalence, and distribution of PTSD in Rwandan population. It is also the first review that summarizes epidemiology of PTSD in the context of Rwanda genocide. Another strength is the utilization of broader search terms, which enabled us to obtain more relevant papers to be included in the review. Our review was limited by language criterion, as only studies published in English were included in the review. Limitations of our review also include the use of retrospective studies and studies with very small sample size. In addition, some of the studies utilized tools which are not appropriate for PTSD diagnosis although they are important for assessing PTSD symptoms. We therefore admit that the limitations observed may have affected our interpretation of the results. To our knowledge, metanalysis study on the prevalence of PTSD is the first conducted in Rwanda context.

4.1. Policy implications

The results of these studies will advance the scope of health research towards better management and treatment of mental health disorders in the country as well as in post conflict zones across the world. Longitudinal studies are recommended to investigate the impact of genocide exposure with changes at the level of genome and DNA methylation profiles in relation to the development of PTSD symptoms more broadly. The current evidence on epidemiological profile of PTSD in Rwandan population may be important in orienting policy makers in strengthening existing interventions to alleviate the burden of PTSD and its comorbidity in Rwanda.

5. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge few studies have reported the burden of PTSD prevalence in African post conflict zones, particularly in Rwanda. Post-genocide PTSD prevalence in Rwanda is comparable to that in other nations that have endured major mass traumas such as war, genocide and forced migration. The burden of PTSD in the general Rwandan population declined significantly over time, likely due to treatment of symptoms through strong national mental health programs, peace building and resolution of symptoms over time.

Highlights.

Post-genocide PTSD prevalence in Rwanda is comparable to that in other nations that have endured major mass traumas such as war, genocide and forced migration.

The burden of PTSD in the general Rwandan population declined significantly over time, likely due to treatment of symptoms through strong national mental health programs, peace building and resolution of symptoms over time.

Specific cohorts, such as military cohorts, contribute to the heterogeneity of these findings and need to be distinguished from other cohorts to determine more accurate PTSD prevalence estimates

Acknowledgements

NIH Grant U01MH115485-01 supported this over all work by a doctoral scholarship. The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts. The authors recognize the advanced capacity building program on evidence-based health care focusing on systematic review and metanalysis provided by Rwanda Biomedical Center and Evidence-Based Healthcare center: Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) under the support from Clinton Health Access Initiative Rwanda.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

References

- 1.Cobain RN. When Nothing Matters Anymore: A Survival Guide for Depressed Teens: Easyread Super Large 24pt Edition 2009;(February):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Departmentof Veterans Affairs D, Health Administration V, Health Strategic Healthcare Group M, Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder N. Understanding PTSD and PTSD Treatment. 2017;(September):1–16. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/understanding_ptsd/booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, Mclaughlin KA, Health M, Africa S. HHS Public Access. 2015;28(4):307–311. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167.Epidemiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugisha J, Muyinda H, Wandiembe P, Kinyanda E. Prevalence and factors associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder seven years after the conflict in three districts in northern Uganda (The Wayo-Nero Study). BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1). doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0551-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandrup L, Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in Ugandan Youth. 2014;(August):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veling W, Hall BJ, Joosse P. The association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and functional impairment during ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perroud N, Rutembesa E, Paoloni-Giacobino A, et al. The Tutsi genocide and transgenerational transmission of maternal stress: Epigenetics and biology of the HPA axis. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(4):334–345. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.866693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations. Rwandan Genocide. 2007:2013 http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/education/rwandagenocide.shtml.

- 10.Munyandamutsa N, Nkubamugisha PM, Gex-Fabry M, Eytan A. Mental and physical health in Rwanda 14 years after the genocide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(11):1753–1761. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0494-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onyut LP, Neuner F, Ertl V, Schauer E, Odenwald M, Elbert T. Trauma, poverty and mental health among Somali and Rwandese refugees living in an African refugee settlement – an epidemiological study. Confl Health. 2009;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-3-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harbertson J, Grillo M, Zimulinda E, et al. Prevalence of PTSD and depression, and associated sexual risk factors, among male Rwanda Defense Forces military personnel. Trop Med Int Heal. 2013;18(8):925–933. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaal S, Weierstall R, Dusingizemungu J, Elbert T. Mental Health 15 Years After the Killings in Rwanda : Imprisoned Perpetrators of the Genocide Against the Tutsi Versus a Community Sample of Survivors. 2012;(August):446–453. doi: 10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neugebauer R, Fisher PW, Turner JB, Yamabe S, Sarsfield JA. Post-traumatic stress reactions among Rwandan children and adolescents in the early aftermath of genocide. 2009;(February):1033–1045. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eroglu S, Toprak S, Urgan O MD, Ozge E. Onur MD, Arzu Denizbasi MD, Haldun Akoglu MD, Cigdem Ozpolat MD, Ebru Akoglu. DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. Vol 33; 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703993104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joanna T JBI SR resource package. 2015.

- 17.Wang N How to Conduct a Meta-Analysis of Proportions in R : A Comprehensive Tutorial Conducting Meta-Analyses of Proportions in R. John Jay Coll Crim Justice. 2018;(June):0–62. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27199.00161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.JBI SUMARI manual. 2017;(April). http://joannabriggs.org/sumari.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francisco ARL. 済無No Title No Title. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53(9):1689–1699. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.00423800267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):153–160. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivanov ML, Weber O, Gholam-Rezaee M, et al. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a psychiatric emergency setting. Eur J Psychiatry. 2012;26(3):159–168. doi: 10.4321/S0213-61632012000300002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska J a., Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Pap Present Annu Meet Int Soc Trauma Stress Stud San Antonio, TX, October, 1993 1993;2:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foa EB. PTSD Scale - Self report for DSM 5. 2013;5:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Prins A, et al. BRIEF REPORT: Utility of a short screening scale for DSM-IV PTSD in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):65–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00292.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vukojevic V, Kolassa I-T, Fastenrath M, et al. Epigenetic Modification of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Is Linked to Traumatic Memory and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Risk in Genocide Survivors. J Neurosci. 2014;34(31):10274–10284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1526-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer A, Kolassa S, Freytag V, et al. Integrated genetic , epigenetic , and gene set enrichment analyses identify NOTCH as a potential mediator for PTSD risk after trauma : Results from two independent African cohorts. 2018;(August):1–14. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.RWANDA MENTAL HEALTH SURVEY Draft Report January 2019. 2019;(January). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joop T. V. M. de Jong, Komproe Ivan H., Van Ommeren Mark, Masri Mustafa El, Araya Mesfin, Noureddine Khaled, Willem van de Put DS. Lifetime Events and PosttraumaticStress Disorder in 4 Postconflict Settings. JAMA 2001;286:555–562. 1990;286(February):371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clare L Middlesex University Research Repository : an open access repository of. 2011:1–76.

- 30.A JN, C H, E M, B D. Holocaust survivors: The pain behind the agony. Increased prevalence of fibromyalgia among Holocaust survivors. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(6). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joffe C, Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Ehrlich F. The Sydney Holocaust study: Posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychosocial morbidity in an aged community sample. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(1):39–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1022059311147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pham PN, Weinstein HM, Longman T. Trauma and PTSD Symptoms in Rwanda. JAMA. 2004;292(5):602. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis, et al. 2019. Healing Trauma and Building Trust and Tolerance in Rwanda Healing Trauma and Building Trust and Tolerance in Rwanda. Peace Build Pract. 2019;4(4). [Google Scholar]

- 34.RAND. RAND Promoting Psychologica LResilience US Military; 2011.

- 35.Adler AB, Williams J, Mcgurk D, Moss A, Bliese PD. Resilience training with soldiers during basic combat training: Randomisation by platoon. Appl Psychol Heal Well-Being. 2015;7(1):85–107. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson SR, Dobbins S. The Applicability of Resilience Training to the Mitigation of Trauma-Related Mental Illness in Military Personnel. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2018;24(1):23–34. doi: 10.1177/1078390317739957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yehuda R, Lehrner A, Bierer LM, Gerlinde M. The public reception of putative epigenetic mechanisms in the transgenerational effects of trauma. Environ Epigenetics. 2018;4(2):1–7. doi: 10.1093/eep/dvy018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]