Abstract

One of the key components in controlling fluid streams in microfluidic devices is the valve and gating modules. In most of the situations, these components are fixed at specific locations, and new reconfiguration of microchannels requires costly and laborious fabrication of new devices. In this study, inspired by human vasculature microcapillary reconfiguration in response to blood transport requirements, the idea of reconfigurable gel microfluidic systems is presented for the first time. A simple approach is described to print microchannels in methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) hydrogels by using agarose fibers that are loaded with iron microparticles. The agarose fibers can then be used as valves, which are then manipulated using a permanent magnet, providing the reconfigurability of the system. The feasibility of agarose gels is tested with different iron microparticles loadings as well as its resistance to fluid flows. Further, it is shown that using this technique, multiple configurations, as well as reconfigurability, are possible from a single device. This work opens the framework to design more intricate and reconfigurable microfluidic devices, which will decrease the cost and size of the final product.

Microfluidics is the science of manipulating or processing of minute amounts of fluids in microdevices.(1) It offers the ability to reduce expensive reagents and reaction times, as well as the possibility of miniaturizing complex laboratorial operations.(2) Developments in microfabrication techniques and utilization of microfluidic devices for fluid transport has found numerous applications, including in pharmaceutics, biomedicine(3, 4) rapid chemical analyses(5, 6) printing(7) high-throughput screening(8) and non-invasive diagnostics(9) to name a few. More specifically, this technology has demonstrated great potential to change the way conventional biology is done in recent years.(10, 11) In addressing the integration of microfluidics and biology, the concept of hydrogel microfluidics has become particularly attractive, especially in the context of stem cells and tissue engineering. In hydrogel microfluidics, microchannels are fabricated into the gel matrix via standard microfabrication techniques(12) or 3D printing,(13–15) and cells can either be embedded within the matrix material or seeded directly into the microchannels without the need for a protein coating - both which are not possible with more conventional PDMS or plastic microdevices. Combined, these advantages justify the broad interest for this technique in the field of cell biology and tissue regeneration.

One of the key components of microfluidic devices that allow for complex operation of fluid control consists of valving and gating systems.(16) In general, these systems allow the user to control fluid routing, timing, and separation within a device by varying pre-defined parameters, such as voltage and temperature.(17) Therefore, microfluidic gates and valves represent one of the most fundamental enablers of many microfluidic operations. Many types of microfluidic valves have been reported in the literature. These have included pneumatic,(18–20) electric(21, 22) piezoelectric,(23) pH,(24) thermally actuated(25, 26) and phase change valves.(16, 27–29) However, one key requirement that enables microvalves to function is that they must be fixed to a pre-determined location relative to the microchannel design, as to allow for channel opening and closing, and thus determine the directionality of a fluidic pathway. In practice, this means that a device must be built with a pre-determined configuration of valves and channels, and as such, reconfiguration of a fluidic path requires fabrication of a new device or addition of a new set of valves. This is an important limitation since microdevice fabrication is costly and time-consuming. Importantly, this becomes particularly challenging for microfluidic hydrogels, since the majority of valving systems are only optimized for rigid/elastomeric materials, and are not easily transferable to soft hydrogels that are commonly used in cell biology.

Here, we propose a novel concept for reconfiguration of hydrogel microfluidic devices, where multiple fluidic pathways can be generated via reversible manipulation of 3D printed iron microparticles loaded fibers inside of microfluidic channels using an automated magnetic system. Different from conventional microfluidic devices, which are constrained to a limited number of flow configurations, this unique functionality allows for the generation of several fluidic pathways without the need for fabrication of multiple devices, or incorporation of fixed valves within the device material, which is currently not possible in the field.

The proposed ability to reversibly reconfigure the microfluidic device is inspired by the ability of the human vasculature to rearrange its pathways as a function of blood transport requirements. Accordingly, as oxygenation of an ischemic area becomes necessary, blood capillaries open up to enable increased blood flow to desired areas, whereas existing vessels regress to shut down excessive capillary flow where oxygen equilibrium is already established.(30) We mimic this functionality by 3D printing microchannels in methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) hydrogels by using agarose fibers that are loaded with iron microparticles as an ink. We have previously demonstrated that agarose fibers can be 3D printed to pre-determined locations, and upon coverage with methacrylated hydrogels followed by photopolymerization, the fibers can be removed out of the crosslinked material, leaving a trail of hollow and empty channels behind.(13) In the current work, we adopt a similar strategy using agarose fibers loaded with iron microparticles, and after printing, the fibers are manipulated inside of the engineered microchannels using a magnet assembled at the end of a metallic piston connected to an automated X-Y robotic arm (i.e., 3D printer) (Figure 1). Rastering of the robotic arm above the agarose fibers using the printing coordinates set by the extrusion software allows for the automated movement of the printed fibers inside of the fabricated channels. Overall, the controlled and reversible movement of the magnetic assembly allows for controllable gating of microchannels, and easy reconfiguration of fluidic paths as necessary. It should be noted that we used a 3D printer in order to illustrate that the process could be accomplished with an off- the-shelf, simple and readily available option. However, any X-Y robotic system could be used for manipulation of the magnetic fibers

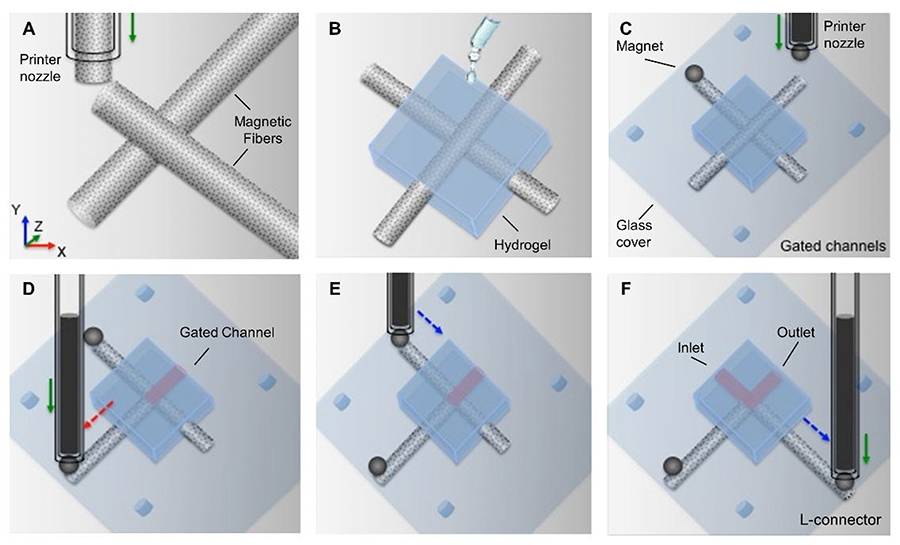

Figure 1.

Procedures for fabricating a reconfigurable microfluidic junction: a) a 3D printer was used to print two perpendicular magnetic agarose gel fibers on a glass slide, b) the GelMA solution was cast on the fibers and exposed to UV light for curing, c) spherical magnets were placed at the end of the fibers, d) the printer nozzle was used to move the magnetic fibers inside the gel. By moving the magnetic fibers (d, e), a custom configuration (L-connector) could be achieved. f) Finally, the metallic piston is moved upward, and the magnet is released.

For proof of principle, we have demonstrated independent control of fluidic pathways in a simple two-channel hydrogel microdevice, as schematically depicted in Figure 1. In this device, two perpendicular magnetic agarose gel fibers were created using a customized extrusion 3D printer. Firstly, a 500 μm glass capillary was immersed into an agarose solution containing iron microparticles and was aspirated using the metallic internal piston. After the agarose solution was gelled, the metallic piston was moved downward to dispense the polymerized material. The printing process was performed at 25 °C with 30 mm/min extrusion speed. The 10% GelMA hydrogel solution was cast onto the extruded fibers and exposed to UV light (Figure 1b). The metallic piston within the printer nozzle was then set to approach a spherical magnet, which was then placed at the end of each of the printed fibers. Next, the robotic arm was set to move at 30 mm/min speed along the fibers to drag the magnet and consequently, the 3D printed fibers inside of the channel (Figure 1c). Upon movement of the magnetic assembly to the desired location, the metallic piston was raised, and the magnet dropped to provide enhanced stability to the positioned fiber against the fluid flow (Figure 1d-f). The movie in the Supplementary Information illustrates the reconfiguration process. This process can be repeated numerous times to enable controllable and reproducible reconfigurability of the device.

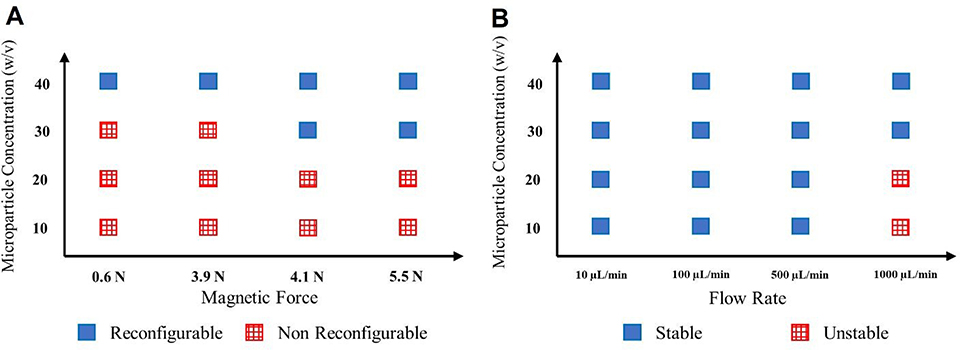

We initially characterized the reconfigurability of simple microdevices using magnets of different strengths and fibers of increasing iron microparticles concentrations to determine the upper and lower thresholds of gating stability. For this purpose, combinations of magnet strengths of 0.6, 3.9, 4.1, and 5.5 N were compared when using fibers containing iron microparticles concentrations of 10, 20, 30, and 40% (w/v). Figure 2a shows that if the iron microparticles concentration was lower than 20% (w/v), the control of magnetic agarose fibers and, consequently, reconfigurability could not be achieved even if the magnet with the highest strength (5.5 N) was used. Additionally, our results suggested that at 30% (w/v) iron microparticles concentration, the reconfigurability could be achieved by using a magnetic force as low as 4.1 N. Moreover, if the iron microparticles concentration was increased to 40% (w/v), magnets with even the lowest magnetic strength (0.6 N) were able to move the fibers inside the channels. Importantly, in our proposed system, not only the magnets allow for controllable movement of the printed fibers inside of the channels, but also they were expected to stabilize the fibers and enhance their ability to resist against fluid flow. To test this proposed effect, we performed flow stability tests to determine the maximum flow rates that the printed fibers could withstand without allowing for fiber movement. Figure 2b shows that the agarose gels with more than 30% (w/v) iron microparticles concentration could withstand fluid flow rates of up to 1000 μL/min. However, if the iron microparticles concentration was reduced to 20% (w/v) or lower, the maximum flow rate that was sustained without leakage was decreased by half (500 μL/min). This decrease in flow rate is basically because the strength of the magnetic interaction between the iron microparticles and magnet cannot overcome the fluidic forces, and the stability of the ‘valve’ is diminished, at which point flow rates above 500 μL/min will displace the fiber. These results prove that magnetic agarose fibers can serve as microchannel gates withstanding high flow rates.

Figure 2.

a) Reconfigurability of the GelMA microfluidic device using magnetic agarose gels with 10–40% (w/v) iron microparticles concentration and magnetic forces ranging from 0.6 to 5.5 N. b) The resistance of magnetic agarose valves with 10–40% (w/v) iron microparticles concentration against 10–1000 μL/min flow rates.

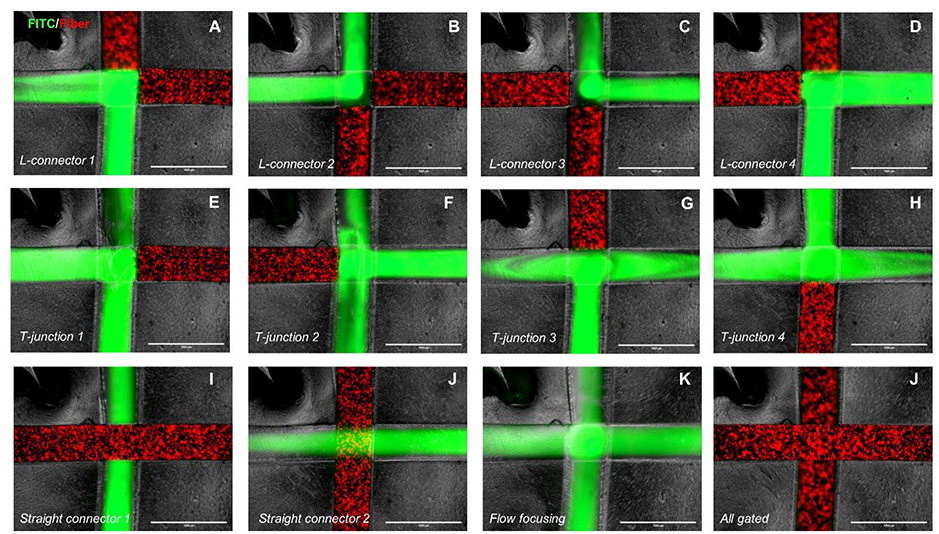

We then selected the 40% (w/v) iron microparticles concentration for the subsequent proof of principle experiments. Using the above-mentioned 4-way junction and magnetic fibers as fluidic gates, 12 different flow paths are shown. Figure 3 illustrates these 12 different configurations consisting of four types of L-connectors or T-junctions, two distinct straight connectors, a flow-focusing configuration, and an all gated device. In order to facilitate visualization of the possible flow paths, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was added to DI water, and a red fluorescent particle was added to the printed fibers. In this initial proof of principle experiment, we have shown fluid flow control in a single 4-way junction. However, it is theoretically possible to control a large number of junctions by 3D printing several magnetic agarose fibers into the microfluidic system and to move them to the desired locations using simple magnets controlled by an automated stage, like that of a 3D printer.

Figure 3.

Twelve different configurations for the fluid flow path in a 4-way junction could be achieved using the proposed reconfigurable method, as explained in the following. a-d) The vertical and horizontal fibers are moved upward/downward and rightward/leftward to create the L connectors. e, f) Horizontal fiber is moved rightward/leftward, while the vertical fiber is moved out of the channel. g, h) Vertical fiber is moved upward/downward, while the horizontal fiber is moved out of the channel. i, j) Horizontal or vertical fiber is taken out of the channel, while the other fiber is not moved. k) Both fibers are taken out of the channels. l) Both fibers are left in their initial locations. The scale bar is 1 mm.

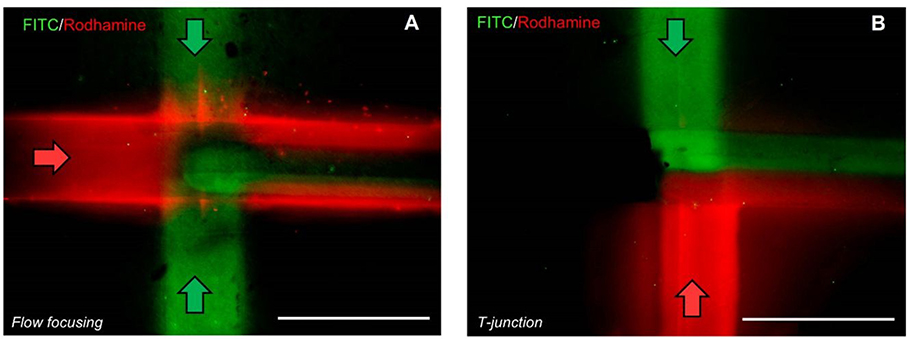

To demonstrate the reconfigurability of a hydrogel microfluidic device in the context of conventional microfluidic experiments, we reconfigured the device from a flow-focusing configuration, into a T-junction configuration with two distinct fluid streams in order to show the ability for independent control of multiple fluids. In the case of flow focusing (Figure 4a), DI water mixed with FITC (Fluid I, green) was entered from top and bottom inlets, while DI water mixed with Rhodamine (Fluid II, red) was pumped from the left inlet. Based on Figure 4a, the perpendicular flow (green) is sheathed by the straight (red) flow. The numerical simulations also prove the same phenomenon (Supplementary Information Figure S1a). This hydrodynamic focusing configuration could be used for a wide range of applications, including mixing, separation, and diffusion-controlled chemical reactions. By moving the magnetic agarose gel to the left channel, a T-junction is created, and Fluid I and II are pumped from the top and bottom junctions, respectively (Figure 4b). Flow behavior is changed due tot he way fluids are introduced as well as the magnetic agarose fibers location. Because of the creeping nature of the fluid flow, mixing occurs in the contact surface between the two fluids, which is also distinctly visible in the experimental as well as simulation results (Supplementary Information Figure S1b). The mixing is usually slow and depends on the diffusion coefficient as well as flow rates.

Figure 4.

The fluid flow behaviors in a) flow focusing and b) T-junction configurations are shown. The scale bar is 1 mm. This image exemplifies the reconfigurability potential of hydrogel microfluidic devices for different applications.

In summary, here we introduce the concept of reconfigurable hydrogel microfluidics, where a simple channel geometry (in this case 2 crossed channels) can give rise to as many as 12 configurations which can be switched back and forth with ease and on-demand, despite the absence of any conventional valves, by simple sliding of microparticle loaded fibers inside the channels using an automated stage. Our results show that by increasing the microparticles concentration to 40% (w/v), all of our available magnets are able to move the 3D printed gel fibers. Moreover, it was shown that agarose gels containing 30% (w/v) and higher microparticles concentrations could withstand fluid flows of up to 1000 μL/min. Although a simple proof of principle is demonstrated, we argue that it is theoretically possible to independently control a large number of microparticles loaded agarose fibers using the method explained above. In order to prove the scalability of the proposed system, a four-junction microfluidic system is fabricated, and magnetic fiber fragments are introduced to the system, and moved to pre-defined locations to obtain the desired flow paths (Figure S2). Our proposed method will allow for the fabrication of complex hydrogel microfluidic devices that can be reconfigured as needed without the need for microvalves, which is currently not possible.

Experimental Section

GelMA synthesis and hydrogel preparation

A 10% (w/v) type A gelatin derived from porcine skin was dissolved into Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline (DPBS) under stirring at 50 °C. The reaction was started by adding 8% (v/v) Methacrylic anhydride with a rate of 0.5 mL/min and maintained the solution at 50 °C for 2 hours. The solution was diluted 2X by adding preheated DPBS at 50 °C and dialyzed using a dialysis tubing (12–14 kDa) against DI water at 48 °C with continuous stirring for seven days. During dialysis, the DI water was changed two times per day, and each time, the dialysis membranes were flipped upside down 6 times to homogenize the content. After dialysis, the GelMA solution was diluted 2X with preheated ultrapure water and was sterilized using Millipore Express Plus (0.22 μm) Stericups. After filtration, the GelMA solution was transferred to falcon tubes and stored horizontally at −80 °C for two days. Finally, the frozen GelMA was lyophilized for 3–4 days, and the resultant white porous foam was stored at −80 °C for further uses. GelMA solutions were prepared by mixing GelMA macromers at a 10% (w/v) concentration with PBS containing 0.5% (w/v) photoinitiator 2- hydroxy-1-(4-(hydroxyethoxy)phenyl)-2-methyl-1-propanone; Irgacure 2959. The GelMA solution was agitated using a vortex mixer and incubated in a convection oven at 80 °C. The agitation/heating process was repeated until the disappearance of the cloudy look of the solution.

Magnetic agarose fiber preparation and printing

Agarose gels were prepared by mixing 6% w/v agarose powder (Sigma-Aldrich) with 10–40% w/v reduced iron microparticles FCC (JT Baker Chemicals) in DI water at 80 °C. The agarose fibers were printed using a customized extrusion 3D printer equipped with XYZ automated stages (Engine SR), and a printer head consisting of a 500 μm glass capillary with an internal piston that is controlled by coordinated movement of a stepper motor. Before printing, the glass capillary was immersed into the iron microparticle-laden agarose solution, and the upward movement of the metallic piston aspirated the gel into the capillary. The material was then allowed to set at room temperature for 30 seconds, and the printing process was performed by dispensing the pre-set iron-laden agarose hydrogel at pre-defined coordinates using the 3D printer set to a 30 mm/min extrusion speed.

GelMA casting and channel reconfiguration

After 3D printing, the printed fibers were cast with 800–1000 μL of GelMA hydrogel precursor in a 2×2 cm PDMS mold, and photopolymerized for 30 seconds, also as described above. After ensuring the moveability of the 3D printed agarose fibers by hand, a 130–170 pm glass coverslip was placed on top of the cured hydrogels, and the magnet was positioned onto the device directly above the printed fiber using the downward movement of the metallic piston in the print-head assembly. The magnet was then rastered onto the surface of the coverslip with a speed of 30 mm/min to result in movement of the magnetic printed fiber inside of the hydrogel microchannel, as depicted in Figure 1. When the fiber was placed in the final configuration, the metallic piston moved upward to release the magnet. For imaging purposes, the iron microparticles-laden fibers were mixed with red fluorescence, while the channels were filled with DI mixed with either FITC or Rhodamine dye via capillary flow to illustrate the reconfiguration of the flow channels.

Reconfigurability and stability tests

For testing of reconfigurability at different iron microparticles concentrations and magnetic strengths, a single fiber of 20 mm in length and 500 μm in diameter loaded with reduced iron microparticles at varying concentrations was printed using the procedure explained above. The printed fibers were cast with 800–1000 μL of GelMA hydrogel precursor in a 2×2 cm PDMS mold and photopolymerized for 30 seconds, also as described above. A 130–170 μm glass coverslip was placed on top of the cured hydrogels, and the magnet was positioned onto the device directly above the printed fiber using the downward movement of the metallic piston in the print-head assembly. The magnet was then rastered onto the surface of the coverslip with a speed of 30 mm/min to result in the movement of the magnetic printed fiber inside of the hydrogel microchannel. Fibers were deemed reconfigurable if the movement was obtained reproducibly for all of the replicates (N=3). For the stability tests, a 23-gauge needle was placed at the channel inlet before GelMA precursor casting. After UV curing, the fibers were moved 5 mm away from the channel inlet, the glass coverslip was positioned, and the magnet was placed on top of the fiber. The fibers were then exposed to flow rates of 10, 100, 500, and 1000 μL/min for at least 60 seconds. Fibers were considered “unstable” if the flow velocity was able to move them in the same direction of the flow. (N=3)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic supplementary information

Electronic Supolementary Information is available at “XXXX”.

References

- 1.Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442(7101):368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riahi R, Tamayol A, Shaegh SAM, Ghaemmaghami AM, Dokmeci MR, Khademhosseini A. Microfluidics for advanced drug delivery systems. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering. 2015;7:101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marimuthu M, Kim S. Microfluidic cell coculture methods for understanding cell biology, analyzing bio/pharmaceuticals, and developing tissue constructs. Analytical biochemistry. 2011;413(2):81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Q, Sun J, Jiang X. Microfluidics-mediated assembly of functional nanoparticles for cancer-related pharmaceutical applications. Nanoscale. 2016;8(25):12430–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh A, Kang D, Xue Y, Lee S, Pielak RM, Kim J, et al. A soft, wearable microfluidic device for the capture, storage, and colorimetric sensing of sweat. Science translational medicine. 2016;8(366):366ra165–366ra165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Z, Yang CJ. Hydrogel droplet microfluidics for high-throughput single molecule/cell analysis. Accounts of chemical research. 2016;50(1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald NP, Cabot JM, Smejkal P, Guijt RM, Paull B, Breadmore MC. Comparing microfluidic performance of three-dimensional (3D) printing platforms. Analytical chemistry. 2017;89(7):3858–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du G, Fang Q, den Toonder JM. Microfluidics for cell-based high throughput screening platforms—A review. Analytica chimica acta. 2016;903:36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey CM, Augustine S, Kumar S, Kumar S, Nara S, Srivastava S, et al. Microfluidics based point - of - care diagnostics. Biotechnology journal. 2018;13(1):1700047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackmann EK, Fulton AL, Beebe DJ. The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research. Nature. 2014;507(7491):181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beebe DJ, Mensing GA, Walker GM. Physics and applications of microfluidics in biology. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2002;4(1):261–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yue X, Nguyen TD, Zellmer V, Zhang S, Zorlutuna P. Stromal cell-laden 3D hydrogel microwell arrays as tumor microenvironment model for studying stiffness dependent stromal cell-cancer interactions. Biomaterials. 2018;170:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertassoni LE, Cecconi M, Manoharan V, Nikkhah M, Hjortnaes J, Cristino AL, et al. Hydrogel bioprinted microchannel networks for vascularization of tissue engineering constructs. Lab on a Chip. 2014;14(13):2202–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JM, Yeong WY. Design and printing strategies in 3D bioprinting of cell - hydrogels: A review. Advanced healthcare materials. 2016;5(22):2856–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowlton S, Yu CH, Ersoy F, Emadi S, Khademhosseini A, Tasoglu S. 3D-printed microfluidic chips with patterned, cell-laden hydrogel constructs. Biofabrication. 2016;8(2):025019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiura S, Sumaru K, Ohi K, Hiroki K, Takagi T, Kanamori T. Photoresponsive polymer gel microvalves controlled by local light irradiation. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2007;140(2):176–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au AK, Lai H, Utela BR, Folch A. Microvalves and micropumps for BioMEMS. Micromachines. 2011;2(2):179–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosokawa K, Maeda R. A pneumatically-actuated three-way microvalve fabricated with polydimethylsiloxane using the membrane transfer technique. Journal of micromechanics and microengineering. 2000;10(3):415. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang X, Lillehoj PB, editors. Pneumatic microvalves fabricated by multi-material 3D printing. 2017 IEEE 12th International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS); 2017: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminaga M, Ishida T, Omata T. Fabrication of Pneumatic Microvalve for Tall Microchannel Using Inclined Lithography. Micromachines. 2016;7(12):224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato K, Shikida M. An electrostatically actuated gas valve with an S-shaped film element. Journal of micromechanics and microengineering. 1994;4(4):205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaible J, Vollmer J, Zengerle R, Sandmaier H, Strobelt T. Electrostatic microvalves in silicon with 2-way-function for industrial applications Transducers’ 01 Eurosensors XV: Springer; 2001. p. 900–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nafea M, Nawabjan A, Ali MSM. A wirelessly-controlled piezoelectric microvalve for regulated drug delivery. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2018;279:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beebe DJ, Moore JS, Bauer JM, Yu Q, Liu RH, Devadoss C, et al. Functional hydrogel structures for autonomous flow control inside microfluidic channels. Nature. 2000;404(6778):588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahra A, Scipinotti R, Caputo D, Nascetti A, de Cesare G. Design and fabrication of microfluidics system integrated with temperature actuated microvalve. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2015;236:206–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu RH, Bonanno J, Yang J, Lenigk R, Grodzinski P. Single-use, thermally actuated paraffin valves for microfluidic applications. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2004;98(2–3):328–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldi A, Gu Y, Loftness PE, Siegel RA, Ziaie B. A hydrogel-actuated environmentally sensitive microvalve for active flow control. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems. 2003;12(5):613–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sershen SR, Mensing GA, Ng M, Halas NJ, Beebe DJ, West JL. Independent optical control of microfluidic valves formed from optomechanically responsive nanocomposite hydrogels. Advanced Materials. 2005;17(11):1366–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pal R, Yang M, Johnson BN, Burke DT, Burns MA. Phase change microvalve for integrated devices. Analytical chemistry. 2004;76(13):3740–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logsdon EA, Finley SD, Popel AS, Gabhann FM. A systems biology view of blood vessel growth and remodelling. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2014;18(8):1491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.