To the editor:

The public health threat posed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may negatively impact on mental wellbeing of the population and significantly increase the risk of mental health problems [1]. In this regard, there are regional differences in mental health which may be affected by sociocultural, economic and environmental factors. In China, the prevalence of mental health problems has been generally higher in the rural areas than their urban counterparts [2,3]. However, little is known about the urban-rural disparities in the occurrence of mental health problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Understanding the regional differences in mental health is essential for planning and implementing targeted intervention and prevention for the general population in the urban and rural areas. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional study from Feb 25 to Mar 17, 2020 among the outpatients in West China Hospital of Sichuan University. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect information pertaining to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, with three specific questions to assess the symptoms of anxiety, depression and insomnia related to COVID-19. For those with an affirmative response to any of these items, they were further assessed by the following questionnaires: 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

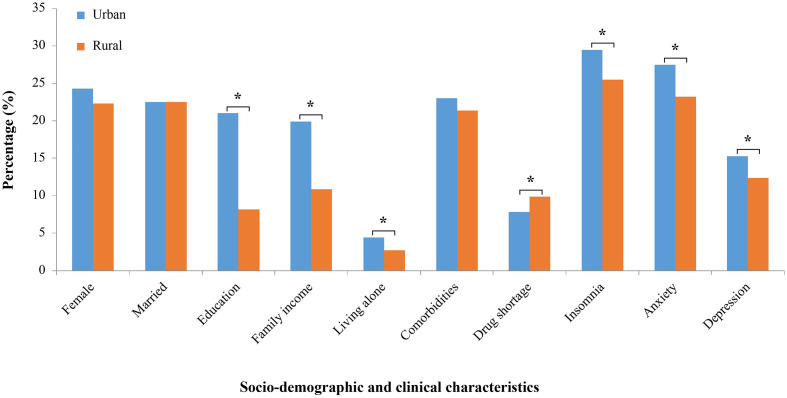

A total of 3068 out of 5025 approached persons (61.1%) completed the survey, including 1928 urban residents and 1140 rural residents. Among the recruited participants, 1110 (36.2%, 714 urban residents and 396 rural residents) reported mental health problems related to the COVID-19 outbreak. In particular, the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia related to the pandemic was 25.9%, 14.2%, and 27.9%, respectively. Notably, there was a significantly higher prevalence of mental health problems in the urban patients compared to their rural counterparts (anxiety: 27.5% vs. 23.2%, depression: 15.3% vs. 12.4%, insomnia: 29.5% vs. 25.5%, all p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the urban and rural participants in terms of age, sex, marital status, and medical comorbidities, except for higher education level and family income, and being more likely to live alone in the urban participants (Fig. 1). There were 369 out of 1110 participants (33.2%) with mental symptoms who reported not being able to receive timely diagnosis and treatment. In particular, rural patients were more affected by the transportation restriction (53% vs. 29.5%, p < 0.001), while urban patients were more likely to express fear of cross-infection in hospitals (48.2% vs. 37.6%, p < 0.05). In addition, rural patients were more likely to face the challenges of the drug shortage (9.9% vs. 7.8%, p < 0.05; Table S1). Logistic regression analysis showed that living with others was a risk factor of anxiety in the urban patients, while being married was associated with a reduced risk of depression in the rural patients. Higher family income and drug shortage were significantly associated with the risk of insomnia in the urban patients, while failing to receive timely diagnosis and treatment was a risk factor of insomnia in the rural patients (Tables S2–S3 and S4).

Fig. 1.

Urban and rural disparities among patients with mental health problems related to COVID-19.

Percentage indicates the percentage of patients with mental symptoms related to COVID-19 in urban and rural areas, respectively. Education indicates education year >12 years and family income indicates family income ≥RMB 5000 /month.

%, the percentage of patients; ⁎p < 0.05.

A total of 3068 out of 5025 approached persons (61.1%) completed the survey, including 1928 urban residents and 1140 rural residents. Among the recruited participants, 1110 (36.2%, 714 urban residents and 396 rural residents) reported mental health problems related to the COVID-19 outbreak. In particular, the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia related to the pandemic was 25.9%, 14.2%, and 27.9%, respectively. Notably, there was a significantly higher prevalence of mental health problems in the urban patients compared to their rural counterparts (anxiety: 27.5% vs. 23.2%, depression: 15.3% vs. 12.4%, insomnia: 29.5% vs. 25.5%, all p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the urban and rural participants in terms of age, sex, marital status, and medical comorbidities, except for higher education level and family income, and being more likely to live alone in the urban participants (Fig. 1). There were 369 out of 1110 participants (33.2%) with mental symptoms who reported not being able to receive timely diagnosis and treatment. In particular, rural patients were more affected by the transportation restriction (53% vs. 29.5%, p < 0.001), while urban patients were more likely to express fear of cross-infection in hospitals (48.2% vs. 37.6%, p < 0.05). In addition, rural patients were more likely to face the challenges of the drug shortage (9.9% vs. 7.8%, p < 0.05; Table S1). Logistic regression analysis showed that living with others was a risk factor of anxiety in the urban patients, while being married was associated with a reduced risk of depression in the rural patients. Higher family income and drug shortage were significantly associated with the risk of insomnia in the urban patients, while failing to receive timely diagnosis and treatment was a risk factor of insomnia in the rural patients (Tables S2–S3 and S4).

Our findings showed that urban residents reported more mental health problems related to COVID-19 outbreak compared to rural residents. This observation was in contrast to the prior finding on a higher prevalence of mental illnesses in the rural areas in China [3]. There might be some possible unique reasons to explain the current findings on a higher prevalence of mental health problems in the urban areas of China due to COVID-19. First, the majority of COVID-19 cases in China were located in the urban areas, which could result in higher sensitivity and vulnerability to the psychosocial effects of the pandemic in the urban residents. Second, the high population density in the urban areas could potentially give rise to a greater risk of spread of virus [4]. Urban residents may experience more stressors due to a higher perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Third, social distancing strategies may increase the risk of loneliness and isolation, which could precipitate depression and anxiety. Urban residents usually were isolated at home with family members in a relatively confined space and their daily life was much more affected due to the restricted activities. Our results indicated that living with others was a risk factor of anxiety among the urban patients, which was consistent with the previous finding on a high level of anxiety in Chinese because of their collective life style [5]. In contrast, the rural residents are predominantly farmers living in more spacious areas, and their activities and mental health might be less affected by social distancing and quarantine measures. Moreover, those residents living in the remote rural areas tended to receive less information about the pandemic due to limited media sources, which might paradoxically decrease the detrimental effects of perceived stress due to the pandemic on mental health. Last, the pandemic might have more significant negative impact on urban residents' work and business due to various precautionary strategies such as social distancing and lockdown, which could potentially explain the higher prevalence of insomnia symptoms in those with higher income. Meanwhile, not being able to timely access health care services because of the transportation restrictions could increase the risk of sleep disturbance in the rural patients.

The observed urban-rural differences in mental health repercussion as influenced by COVID-19 highlight the need to develop appropriate psychiatric services for urban and rural residents. More importantly, the urban-rural differences may shed light on the etiology and management of mental health problems among both urban and rural populations.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Comparisons of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with mental health problems related to COVID-19 between urban and rural areas.

Table S2–S3 Comparisons of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without mental health problems related to COVID-19 in urban and rural areas.

The logistic regression analyses for the risk factors associated with mental health problems related to COVID-19 in urban and rural areas.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.07.011.

Funding source

This work was supported by the Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Agency (grant no. 2020YJ0279).

Ethics committee approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of West China hospital in Sichuan University.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinic nurses in the Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Sleep Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, for their assistance in data collection in this study.

References

- 1.Zhou J., Liu L., Xue P., Yang X., Tang X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(7):574–575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y., Wang Y., Wang H., Liu Z., Yu X., Yan J., et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):211–224. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Xu Y., Nie H., Zhang Y., Wu Y. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the older in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(9):900–906. doi: 10.1002/gps.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delamater P.L., Street E.J., Leslie T.F., Yang Y.T., Jacobsen K.H. Complexity of the basic reproduction number (R0) Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(1):1–4. doi: 10.3201/eid2501.171901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C.N., Wong J., Lee N., Chan-Ho M.W., Lau J.T., Fung M. The Shatin community mental health survey in Hong Kong. II. Major findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):125–133. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparisons of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with mental health problems related to COVID-19 between urban and rural areas.

Table S2–S3 Comparisons of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without mental health problems related to COVID-19 in urban and rural areas.

The logistic regression analyses for the risk factors associated with mental health problems related to COVID-19 in urban and rural areas.