Abstract

Background

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder of the hair follicles, and has been associated with a multitude of systemic disorders and pathologies. There is increasing evidence to suggest that chronic inflammatory skin disorders may be associated with psychiatric comorbidities, however this relationship has not been well established. We aimed perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association between HS and psychiatric comorbidities, suicide and substance abuse.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to PRISMA guidelines.

Results

HS cases had a significantly higher odds of having schizophrenia compared to the control group (OR 1.66, 95% CI: 1.53–1.79, P<0.00001). There was also a significant association with bipolar disorders (OR 1.96,95% CI: 1.65–2.33, P<0.00001), depression (OR 1.75, 95% CI: 1.44–2.13, P<0.00001), anxiety (OR 1.71, 95% CI: 1.51–1.92, P<0.00001), and personality disorders (OR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.18–1.92, P=0.001), suicide (OR 2.08, 95% CI: 1.27–3.42, P=0.004), substance-related disorders (OR 2.84, 95% CI: 2.33–3.46, P<0.00001), and alcohol abuse (OR 1.94, 95% CI: 1.43–2.64, P<0.0001).

Conclusions

For dermatologists treating patients with HS, screening for these comorbidities, psychiatric referral and adequately managing pain will improve the overall wellbeing of patients.

Keywords: Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), psychiatric, depression, anxiety, psychoses, suicide, substance abuse

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder of the hair follicles, characterized by recurrent lesions affecting the apocrine glands including nodules, abscesses, fistulas and draining sinus tracts.

Although not contagious or life-threatening, HS is associated with significant discomfort and potential disfigurement, which can have a negative effect on patient quality of life and confidence. HS may be associated with patient embarrassment, social stigma, and can have a detrimental impact on interpersonal relationships (1). There is increasing evidence suggesting that this may lead to psychiatric comorbidities including depression and anxiety disorders (2,3). Additionally, there is increasing evidence to suggest that chronic inflammatory skin disorders may be associated with psychiatric comorbidities, particularly conditions including psoriasis and eczema (4,5). For patients with HS, an Italian survey study has demonstrated that up to one-quarter of patients may have at least one underlying diagnosis of psychiatric comorbidity (4).

There remains lack of synthesised data in the literature exploring the relationship between HS and psychiatric disorders. Understanding the full spectrum of comorbidities of HS would have clinical implications for physicians caring of this population. To address limitations in the literature, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine which psychiatric comorbidities HS may have an association with. We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist.

Methods

Search strategy

As no humans or animals were involved in this study, and all data is readily available on electronic database in published format, ethics approval was waived for this study. The present systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to recommended PRISMA guidelines (6). As no human or animal subjects were involved in this study, ethics approval was not required. Electronic searches were performed using Ovid Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), ACP Journal Club and Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness (DARE) from their dates of inception to 8th December 2018. To achieve maximum sensitivity of the search strategy and identify all studies, we combined the terms: “hidradenitis suppurativa”, “acne inversa”, “psychiatric”, “psychological”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “psychosis”, “bipolar”, “schizophrenia”, “personality disorder”, “substance abuse”, “alcohol abuse”, “suicide”, “self-harm”, as either keywords or MeSH terms (Table S1). The reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies. All identified articles were systematically assessed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table S1. Search strategy used in the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

| Number | Search | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | hidradenitis suppurativa.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 5,256 |

| 2 | acne inversa.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 770 |

| 3 | psychiatric.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 560,257 |

| 4 | psychological.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 1,237,948 |

| 5 | depression.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 1,062,285 |

| 6 | anxiety.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 590,424 |

| 7 | psychosis.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 159,963 |

| 8 | bipolar.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 186,833 |

| 9 | schizophrenia.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 342,179 |

| 10 | personality disorder.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 73,394 |

| 11 | substance abuse.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 120,877 |

| 12 | alcohol abuse.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 54,600 |

| 13 | suicide.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 182,295 |

| 14 | self-harm.mp. [mp=ti, ot, ab, tx, kw, ct, sh, hw, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, dq, nm, kf, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy] | 12,236 |

| 15 | (1 or 2) and (3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14) | 212 |

Selection criteria

All eligible case-control studies comparing patients with HS versus non-HS were included in the present review. All studies must have included either the proportion of patients with a psychiatric comorbidity, suicide or substance abuse, or the summary effect size for association between HS and the above factors. Psychiatric comorbidities included depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, anxiety disorder, or personality disorder. When institutions published duplicate studies with accumulating numbers of patients or increased lengths of follow-up, only the most complete reports were included for quantitative assessment at each time interval. All publications were limited to those involving human subjects. Language was not an exclusion criterion. Case reports, editorials, letters and expert opinions were excluded. Review articles were omitted because of potential publication bias and result duplication.

Data extraction and critical appraisal

Information was extracted from article texts, tables and figures. Data collected included study characteristics, the proportion of patients with psychiatric comorbidity, suicide or substance abuse in the HS cohort versus non-HS control cohort. If the proportion data was not available, then effect size either in the form of odds ratio, relative risk or hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval was collected. Each study was then assessed against the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (7) which accounted for criteria such as selection, comparability, and outcome to evaluate the quality of its design.

Statistical analysis

The odds ratio (OR) was used as a summary statistic. In the present study, random-effects model was tested, where it was assumed that there were variations between studies. Random-effects model were presented to take into account the possible clinical diversity and methodological variation between studies. χ2 tests were used to study heterogeneity between trials. I2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of total variation across studies, owing to heterogeneity rather than chance, with values greater than 50% considered as substantial heterogeneity. I2 can be calculated as: I2= 100% × (Q – df)/Q, with Q defined as Cochrane’s heterogeneity statistics and df defined as degree of freedom Specific analyses considering confounding factors were not possible because raw data were not available. All P values were 2-sided. All statistical analysis was conducted with Review Manager Version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Results

Literature search

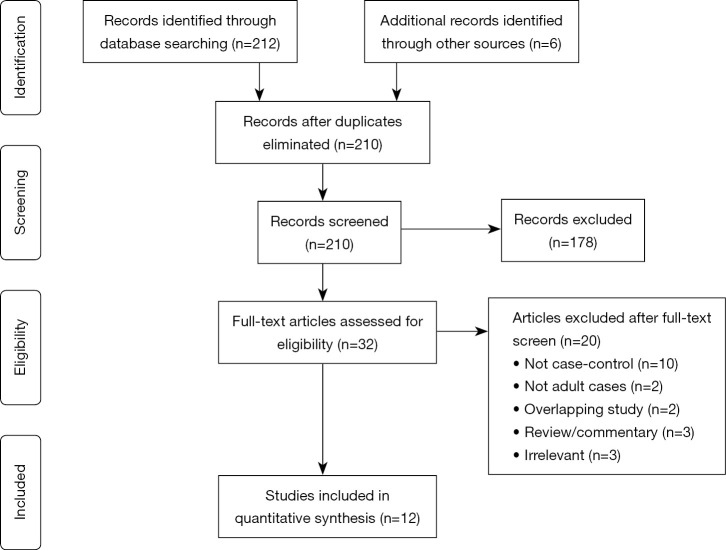

A total of 212 studies were identified through electronic database search and from other sources such as reference lists (Figure S1). After removal of duplicates, title and abstract screening, and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, there was a final 12 articles (2,3,8-17) included for meta-analysis. Of these, 4 studies (3,9,11,12) reported data on schizophrenia, 3 studies (3,9,11) on bipolar disorders, 8 studies (2,3,9-13,15) on depression, 5 studies (3,9,11,12,15) on anxiety disorders, 3 studies (9,11,12) on personality disorders, 4 studies (8,12,15,17) on suicide, 3 studies (11,12,16) on substance-related disorders, and 5 studies (11,12,14,16) on alcohol abuse. There were 2 studies (8,16) analysing patient data from the same database, however reporting different outcomes and as such both studies were included in the present review. There were another 2 studies (9,17) analysing the same Finnish patient database, but reporting separate outcomes. The details of included studies are displayed in Table 1.

Figure S1.

PRISMA flow chart of search strategy.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies in the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | Number of patients | Country | Data source | Identification of cases | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | Control | ||||||

| Garg | 2017 | 49,380 | 23,153,180 | United States | Multi-health system data analytics and research platform (Explorys) | Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) of ‘hidradenitis’ and ;suicide’ | General population participants in the database without diagnosis of HS |

| Garg | 2018 | 32,625 | 9,581,640 | United States | Multi-health system data analytics and research platform (Explorys) | SNOMED-CT term ‘hidradenitis’ has one-to-one mapping to the ICD-9 codes 705.83, and was used to identify patients with HS | General population participants in the database without diagnosis of HS |

| Huilaja (psoriasis controls) | 2018 | 4,337 | 17,318 | Finland | Finnish Care Register for Health Care maintained by the National Institute of Health and Welfare | ICD-9 codes 7058C and ICD-10 code L73.2 | Patients diagnosed with psoriasis (ICD-9 codes 6918B, 6961A and ICD-10 code L40.0) or benign melanocytic nevi (ICD-9 codes 2160-9A and ICD-10 codes D22) |

| Ingram (proxy cases) | 2018 | 69,842 | 93,869 | United Kingdom | U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) linked to hospital episode statistics data | To capture undiagnosed cases, patients were identified from those attending primary care for multiple skin boil consultations | General population participants in the database without diagnosis of HS |

| Ingram (physician diagnosed cases) | 2018 | 24,027 | 93,869 | United Kingdom | U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) linked to hospital episode statistics data | Physician-diagnosed cases of HS were captured by codes M25y100 (Hidradenitis) and M25y111 (Hidradenitis suppurativa) | General population participants in the database without diagnosis of HS |

| Kimball (mild HS) | 2018 | 2,292 | 2,292 | United States | OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc. database (January 1999–March 2014), an administrative claims database | Patients who received at least one code ICD-9 code for HS (705.83) | Database controls—cases without diagnosis of HS |

| Kimball (severe HS) | 2018 | 3,065 | 3,065 | United States | OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc. database (January 1999–March 2014), an administrative claims database | Patients who received at least one code ICD-9 code for HS (705.83) | Database controls—cases without diagnosis of HS |

| Onderdijk | 2013 | 211 | 233 | Netherlands, Denmark | Patient records from Departments of Dermatology, at Deventer Hospital in the Netherlands and Roskilde Hospital in Denmark, from March to November 2009 | Diagnoses by dermatologist in the department, as per definitions of HS-Foundation Research meeting in 2009 | The controls did not have HS, (20–60 years old) and were selected among patients attending the out-patient department |

| Patel | 2018 | 24,666 | 87,028,489 | United States | 2002-2012 National Inpatient Sample | ICD-9-CM code 705.83 | Same database, hospitalizations without any diagnosis of HS |

| Riis | 2018 | 500 | 27,265 | Denmark | Danish Blood Donor Study cohort | Questionnaire has been developed for the diagnosis of HS, using two simple questions—(I) ‘Have you had an outbreak of boils during the last 6 months?’ and (II) ‘Where and how many boils have you had?’—listing these locations: axilla, groin, genitals, under the breast and other location. We defined HS as an affirmative answer to question 1, combined with more than two boils in total for question 2 | Blood donors without diagnosis of HS |

| Shavit | 2015 | 3,207 | 6,412 | Israel | cross-sectional study using data mining techniques utilizing the Clalit database in Israel | At least one documented diagnosis of HS in the medical records between 1997 and 2011, registered by a Clalit dermatologist (3,207 patients) | Age and gender matched participants without diagnosis of HS |

| Shlyankevich | 2014 | 1,730 | 1,730 | United States | Retrospective chart analysis of the Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR) at Massachusetts General Hospital | Patients who received at least one code ICD-9 code for HS (705.83). Diagnosis of HS was validated in the medical record by a dermatologist’s confirmation of HS, an accurate description of HS lesions by a reporting physician, or the results of a pathology report | Database searched during same time period to randomly select participants without HS diagnosis |

| Thorlacius | 2018 | 7,732 | 4,354,137 | Denmark | Danish National Patient Register | Recorded diagnosis of HS (ICD-8 code 705.91 and ICD-10 code L73.2) in the Danish National Patient Register | Participants of database, general population without diagnosis of HS |

| Tiri (psoriasis controls) | 2018 | 498 | 8,632 | Finland | Finnish Care Register for Health Care maintained by the National Institute of Health and Welfare | ICD-9, code 7058C and ICD-10 code L73.2 | Patients diagnosed with psoriasis (ICD-9 codes 6918B, 6961A and ICD-10 code L40.0) or benign melanocytic nevi (ICD-9 codes 2160-9A and ICD-10 codes D22) |

Relationship between hidradenitis suppurativa and psychiatric disorders

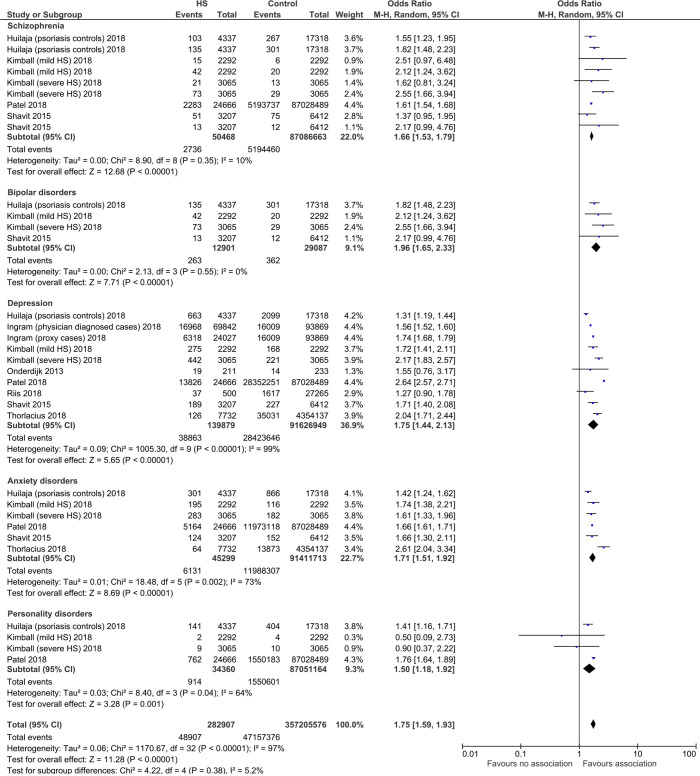

There were 50,468 HS cases compared with 87,086,663 control cases. HS cases had a significantly higher odds of having schizophrenia compared to the control group (OR 1.66, 95% CI: 1.53–1.79, P<0.00001), with no significant heterogeneity (I2=10%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of association between hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and psychiatric commodities including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders.

From 12,901 HS cases compared with 29,087 control cases, there was a significant association found between HS and bipolar disorders compared to controls (OR 1.96, 95% CI: 1.65–2.33, P<0.00001). There was no significant heterogeneity (I2=0%).

From 139,879 HS cases compared with 91,626,949 control cases, there was a significant association between HS and depression comorbidity, compared to controls (OR 1.75, 95% CI: 1.44–2.13, P<0.00001). There was significant heterogeneity (I2=99%).

From 45,299 HS cases compared with 91,411,713 controls, we found a significant association between HS with anxiety disorders compared with controls (OR 1.71, 95% CI: 1.51–1.92, P<0.00001), with significant heterogeneity noted (I2=73%).

For 34,360 HS cases compared with 87,051,164 controls, we found a significant association between HS and personality disorders compared to controls (OR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.18–1.92, P=0.001), with significant heterogeneity (I2=64%).

Overall, we found a significant association between HS and any psychiatric disorder (OR 1.75, 95% CI: 1.59–1.93, P<0.00001).

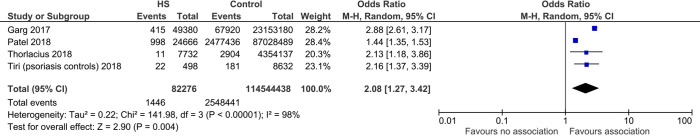

Relationship between hidradenitis suppurativa and suicide

From 82,276 cases compared with 114,544,438 controls, we found a significant association between HS and suicide (OR 2.08, 95% CI: 1.27–3.42, P=0.004). There was significant heterogeneity noted (I2=98%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of association between hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and suicides.

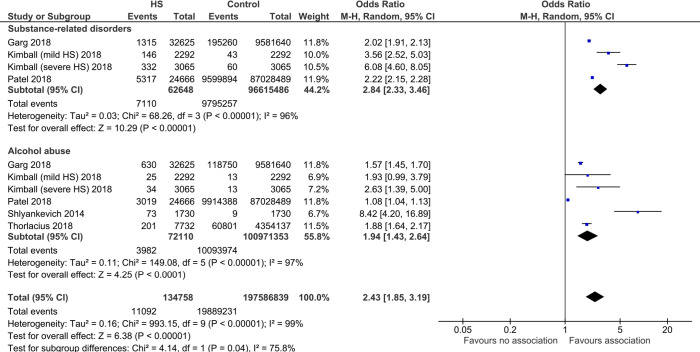

Relationship between hidradenitis suppurativa and substance use

From 62,648 HS cases compared with 96,615,486 controls, we found a significant association between HS with substance-related disorders (OR 2.84, 95% CI: 2.33–3.46, P<0.00001), with significant heterogeneity (I2=96%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of association between hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and substance abuse.

From 72,110 HS cases compared with 100,971,353 controls, we found a significant association between HS and alcohol abuse (OR 1.94, 95% CI: 1.43–2.64, P<0.0001), with significant heterogeneity noted (I2=97%).

Discussion

HS is a debilitating, painful and isolating disease which substantially lowers patients’ quality of life (18,19). This meta-analysis demonstrates that patients with HS are significantly more likely to have substance-related disorders, alcohol abuse, suicide as well as psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety and personality disorders compared to patients without HS. These results highlight the large mental health and drug abuse burden on patients with HS and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to care for patients with HS.

The strongest association found within this meta-analysis was between patients with HS and substance-related disorders, followed by alcohol abuse. A recent large cross-sectional study in United States demonstrated a 4.0% prevalence of substance-related disorders among patients with HS (8). The most common forms of substance misuse were alcohol (47.9%), followed by opioids (32.7%) and cannabis (29.7%) (8). All three of these agents are well-known to reduce pain. In recent qualitative questionnaire study, 85% of patients with HS reported pain as their most difficult symptom (11). Interestingly, the study found the association between HS and substance use disorders was stronger for patients without anxiety or depressive disorder, aged 45–64 years, privately insured and non-whites (8). They speculated that the pain from HS had a stronger influence on the use of substance-related disorders with HS than socioeconomic status, depressive disorder or anxiety disorder. The management of pain is difficult for HS, with first line being simple analgesics, followed by oral opiates (20). Interestingly, anticonvulsants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors possess neuropathic pain-relieving properties that help reduce pain as well as itch and depression (20). This highlights the importance of adequately managing pain from HS lesions, as well as screening for the use of alcohol, opioids and/or cannabis, particularly in those experiencing severe pain from HS. Other factors which may contribute to increased prevalence of substance abuse includes concomitant psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders. These may potentially reduce patient quality of life as well as reduced pain thresholds, both which can lead to higher impact on substance abuse (21).

The third strongest and most concerning association is between HS and suicide, with a two-fold greater risk compared to controls. The increased risk of suicide remained even after adjustment for confounding factors such as presence of depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (15,22). The incidence of completed suicide was 0.29 per 1,000 person-years in patients with HS, compared to 0.14 per 1,000 person-years in those without HS (15). This demonstrates the devastating psychological impact of HS on patient’s lives. Tiri and colleagues (2018) conducted a nationwide registry-based case-control study of 4,373 patients with HS and found women to be at greater risk for suicide than men (22). They found 7% of all deaths in women were due to suicide, compared with 2.7% in men. Although depression was more commonly diagnosed in women than men, depression only affected 11.7% of women who completed suicide compared to 44.9% in men (22). Kouris and colleagues (2016) found women reported a significantly poorer quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index compared to men despite having similar degrees of loneliness, anxiety and depression (23). The poor association between suicide with psychological disorders, particularly in women, highlights the difficulty in identifying patients at risk for suicide and the need for treating physicians to screen for suicidality. Future studies to assess the benefit of screening patient’s quality of life in order to identify those at risk for suicide is warranted.

Depression and anxiety disorders are almost two-fold more likely in patients with HS than those without HS. Higher levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness are seen in those with more severe HS (23). A recent systematic review reported prevalence of depression and anxiety to be 1.6–42.9% and 0.8–3.9% in HS patients, respectively (24). There are a multitude of factors that contribute anxiety and depression for patients with HS. HS is characterised by chronic inflammatory nodules that scar and form sinus tracts which result in patients feeling unattractive, humiliated and anxious that others will find their scars repulsive (1). During periods of flares, lesions are painful, and discharge is malodourous. Patients often take multiple showers a day and change clothes constantly to avoid others from smelling their discharge, isolate themselves from family and friends and cancel social activities (24,25). These lesions are often found in “sensitive” areas such as the genitals and the axilla, leading to a detrimental impact in patient’s sexual health, self-esteem and public image perception (18,26,27). Additionally, patients often experience financial stress due to decreased working hours, with a study reporting 58.1% of employed patients took numerous sick leaves from work (24). Patients are often encouraged by their doctors to cease smoking and lose weight, and the pursuit of these goals results in additional anxiety (28). The many biopsychosocial factors contributing to depression and anxiety highlights the importance of providing multidisciplinary care with the assistance of psychologists and psychiatrists. Additionally, meeting groups for patients with HS have been established in Europe. Many patients with HS find it easier to talk and sympathise with people who have similar problems, reducing their sense of social isolation, developing and learning coping strategies. Finding or establishing such groups within each local health district may be beneficial for patients with HS.

This study also demonstrated schizophrenia and bipolar disorders is significantly associated with HS. This is a problematic association considering a majority of medications used to manage schizophrenia and bipolar disorders significantly increase weight gain (29,30). Weight loss for patients with HS highly recommended as it significantly reduces the number of eruptions and scarring sites in HS (31). Unfortunately, studies have demonstrated patients with schizophrenia are estimated 2 times more likely to be obese (especially women) than those without schizophrenia (32) and up to 84% of patients with bipolar disorder are overweight or obese (33). Olanzapine and clozapine are associated with the greatest weight gain, followed by quetiapine, risperidone, lithium, valproate, gabapentin and some antidepressants (30). Newer agents such as aripiprazole and ziprasidone, as well as carbamazepine and lamotrigine have the lowest propensity for weight gain (30,34). Therefore, these newer agents should be the preferred medications for patients with both HS and schizophrenia or bipolar disorders to reduce weight gain and overall disease burden. Some antipsychotic agents such as lithium have the potential to be acne-generating, which is a further confounding factor.

The pathophysiology between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and HS remains controversial. Chronic inflammation is thought be involved as studies found increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in skin lesions of HS (35,36), as well as in the serum and CSF in those with an exacerbation of schizophrenia (37,38). Two studies suggest that inflammatory molecules may predict subsequent relapse (37,39).

This meta-analysis also found an association between HS and personality disorders. Personality disorders are an entrenched pattern of behaviour that deviates extremely from the norms of generally accepted behaviours and often appear during adolescence. Personality disorders contribute to long term difficulties in functioning in society and in inter-personal relationships. This exacerbates the sense of social isolation, loneliness and lower self-esteem that patients with HS already experience (23). No study in the literature has clarified which type of personality disorder was most common amongst patients with HS. Future studies to identify which types of personality disorders is most common are warranted to improve directed psychosocial support for these patients.

It is unclear to what extent disease severity explains psychiatric symptoms in patients with HS and whether illness perceptions play a role in this. To investigate this, Pavon Blanco (40) and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study of 211 patients with HS and performed multiple questionnaires including Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (BIPQ), the Patient’s Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), as well as Hurley staging for disease severity. The authors found that illness perceptions explained a greater proportion of variance in depression, anxiety and quality of life compared to disease severity (40). As such, the relationship between HS severity and psychiatric disorder symptoms is likely complex, with interplay between multiple patient-factors.

Our findings should be interpreted in view of certain limitations. First, the studies did not assess the timing of disease associations and cannot comment on causation. Future studies should be prospectively conducted to clarify whether HS preceded these psychiatric disorders, or vice versa. Second, there was significant between study heterogeneity for depression, anxiety, personality disorders, suicide and substance abuse. This is likely related the different databases used between studies, with some using a hospital database (15,22), a private insurance database (11), a blood donor database (13) or a national database (9). Hence, the baseline patient characteristics differ between studies based on which databases were used, for example, there may be a selection bias towards more moderate-severe cases of both HS and psychiatric disorders in studies using hospital-based databases. Moreover, another contributing factor for between-study heterogeneity is the different control groups chosen, with one study using patients with psoriasis as the control group (9). However, this meta-analysis also has strengths. This meta-analysis, to the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis which has been reported so far in the literature examining the association between HS and psychiatric disorders and substance abuse.

In summary, the available evidence demonstrates patients with HS are significantly more likely to have substance-related disorders, alcohol abuse, suicide as well as psychiatric issues such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depression, anxiety, personality disorders and substance abuse. Therefore, for dermatologists treating patients with HS, screening for these comorbidities, psychiatric referral and adequately managing pain will improve the overall wellbeing of patients.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring questions related to accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. As no humans or animals were involved in this study, and all data is readily available on electronic database in published format, ethics approval was waived for this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1028). SDS reports non-financial support from Abbvie advisory board, personal fees from Abbvie speaker, other from Abbvie Principal Investigator, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Esmann S, Jemec GB. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study. Acta Derm Venereol 2011;91:328-32. 10.2340/00015555-1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onderdijk AJ, Van der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:473-8. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:371-6. 10.1111/jdv.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picardi A, Abeni D, Melchi CF, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: an issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:983-91. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:891-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264-9, w64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wells G. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non randomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www ohri ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford asp. 2001.

- 8.Garg A, Pomerantz H, Midura M, et al. Completed suicide in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: A population analysis in the United States. J Investig Dermatol 2018;137. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huilaja L, Tiri H, Jokelainen J, et al. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have a high psychiatric disease burden: a Finnish nationwide registry study. J Investig Dermatol. 2018;138:46-51. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:917-24. 10.1111/bjd.16101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimball AB, Sundaram M, Banderas B, et al. Development and initial psychometric evaluation of patient-reported outcome questionnaires to evaluate the symptoms and impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat 2018;29:152-64. 10.1080/09546634.2017.1341614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel KR, Rastogi S, Singam V, et al. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa and hospitalization for psychiatric disorders: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Inpatient Sample. Br J Dermatol 2019;181:275-81. 10.1111/bjd.17416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theut Riis P, Pedersen O, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self‐reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross‐sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2019;180:774-81. 10.1111/bjd.16998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:1144-50. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, et al. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Investig Dermatol 2018;138:52-7. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Opioid, alcohol, and cannabis misuse among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: A population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;79:495-500.e1. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiri H, Huilaja L, Jokelainen J, et al. Women with Hidradenitis Suppurativa Have an Elevated Risk of Suicide. J Investig Dermatol 2018;138:2672-4. 10.1016/j.jid.2018.06.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deckers IE, Kimball AB. The Handicap of Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatol Clin 2016;34:17-22. 10.1016/j.det.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gooderham M, Papp K. The psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73:S19-S22. 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73:S47-S51. 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aldana PC, Driscoll MS. Is substance use disorder more prevalent in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa? Int J Womens Dermatol 2019;5:335-9. 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;79:514-9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial implications in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2016;232:687-91. 10.1159/000453355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matusiak Ł. Profound consequences of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review. Br J Dermatol 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/bjd.16603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joachim G, Acorn S. Stigma of visible and invisible chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:243-8. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janse IC, Deckers I, van der Maten A, et al. Sexual health and quality of life are impaired in hidradenitis suppurativa: a multicentre cross‐sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:1042-7. 10.1111/bjd.14975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurek A, Peters EM, Chanwangpong A, et al. Profound disturbances of sexual health in patients with acne inversa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:422-8.e1. 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec G, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:831-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panariello F, De Luca V, de Bartolomeis A. Weight gain, schizophrenia and antipsychotics: new findings from animal model and pharmacogenomic studies. Schizophr Res Treatment 2011;2011:459284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Torrent C, Amann B, Sánchez‐Moreno J, et al. Weight gain in bipolar disorder: pharmacological treatment as a contributing factor. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008;118:4-18. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kromann CB, Ibier KS, Kristiansen VB, et al. The influence of body weight on the prevalence and severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:553-7. 10.2340/00015555-1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saddichha S, Manjunatha N, Ameen S, et al. Effect of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol treatment on weight and body mass index in first-episode schizophrenia patients in India: a randomized, double-blind, controlled, prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1793-8. 10.4088/JCP.v68n1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McElroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, et al. Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:207-13. 10.4088/JCP.v63n0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31-41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly G, Prens EP. Inflammatory mechanisms in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin 2016;34:51-8. 10.1016/j.det.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, Van Den Broecke D, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐1β and IL‐10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF‐α and IL‐1β. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:1292-8. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganguli R, Gubbi A. Clinical and immunological characteristics of a subgroup of patients suffering from schizophrenia. In: Henneberg AE, Kaschka WP. editors. Immunological Alterations in Psychiatric Diseases. Adv Biol Psychiatry 1997;18:35-43. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, et al. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry 2011;70:663-71. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAllister CG, Kammen DP, Rehn TI, et al. Increases in CSF levels of interleukin-2 in schizophrenia: effects of recurrence of psychosis and medication status. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1291-7. 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavon Blanco A, Turner M, Petrof G, et al. To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? Br J Dermatol 2019;180:338-45. 10.1111/bjd.17123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as