Abstract

Chronic high sodium intake is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease as it impairs vascular function through an increase in oxidative stress. The objective of this study was to investigate the acute effects of a high sodium meal (HSM) and antioxidant (AO) cocktail on vascular function. We hypothesized that a HSM would impair endothelial function, and increase arterial stiffness and wave reflection, while ingestion of the AO cocktail would mitigate this response. Healthy adults ingested either an AO cocktail (vitamin C, E, alpha-lipoic acid) or placebo (PLA) followed by a HSM (1,500 mg) in a randomized crossover blinded design. Blood pressure (BP), endothelial function (flow-mediated dilation; FMD) and measures of arterial stiffness (pulse wave velocity; PWV) and wave reflection (augmentation index; AIx) were made at baseline and 30, 60, 90, and 120min after meal consumption. Forty-one participants (20M/21W; 24±1 years; BMI 23.4±0.4 kg/m2) completed the study. Mean BP increased at 120min relative to 60min (60min: 79 ± 1; 120min: 81 ± 1 mmHg; time effect p=0.01) but was not different between treatments (treatment × time interaction p=0.32). AIx decreased from baseline (time effect p<0.001) but was not different between treatments (treatment × time interaction p=0.31). PWV (treatment × time interaction, p=0.91) and FMD (treatment × time interaction p=0.65) were also not different between treatments. In conclusion, a HSM does not acutely impair vascular function suggesting young healthy adults can withstand the acute impact of sodium on the vasculature and therefore, the AO cocktail is not necessary to mitigate the response.

Keywords: sodium, salt, antioxidants, humans, vascular function

1. INTRODUCTION

Diets high in sodium are a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1, 2]. A recent systematic analysis on the health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries highlighted sodium as one of the leading dietary risk factors for deaths and disability-adjusted lifestyle years [3]. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommend no more than 2,300 mg of sodium as a daily intake [4]. Despite this, American adults continue to consume 1.5 times the amount recommended by the DGA at 3,400 mg of sodium per day [4, 5]. While the role of excess sodium intake in contributing to high blood pressure (BP) is well known, work over the last decade has illustrated that high sodium diets can impair the vascular endothelium independent of changes in BP [6–10].

Endothelial dysfunction is a non-traditional risk factor for atherosclerosis [11] and subsequent cardiovascular disease [12]. We have previously shown that healthy salt-resistant adults exhibit impaired endothelial function as evidenced by reduced brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) following one week of a high sodium diet [6, 10]. Furthermore, it appears that one-week of a high sodium diet has a more deleterious effect on vascular function in men compared to women [8].

Arterial stiffness and wave reflection are independent predictors of cardiovascular health outcomes [13, 14]. Large cohort studies indicate a high sodium intake is associated with increased pulse wave velocity (PWV) [15, 16], a measure of arterial stiffness. A recently published meta-analysis of 11 pooled randomized controlled trials of 1–6 weeks in duration concluded that lowering sodium intake reduces PWV [17]. Augmentation index (AIx), a measure of wave reflection, was increased in healthy men who consumed a high sodium diet for 6 weeks [18] and we have demonstrated that even 7 days of a high sodium intake increases forward and reflected wave amplitudes in middle-aged healthy adults [19].

Acutely, the nutrient composition of a meal can impact vascular function. Meals high in fat [20–22] or the addition of refined sugars [23, 24] reduce endothelial function. Dickinson et al. [25] demonstrated that a high sodium meal (HSM) acutely reduced post-prandial FMD more than a low sodium meal. A HSM also increased AIx as compared to a low sodium meal [26]. However, the average age of subjects in these studies was 37 years with a wide range (18 to 70 years), and therefore it is not clear if inclusion of the older subjects may have influenced the results as FMD reduces and wave reflection increases with age [27, 28]. Hence, we chose to study a narrower age range.

While the mechanisms behind the deleterious role of sodium on the vasculature are not completely known, evidence suggests that increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play a role [29, 30]. Studies in adults (mean ages 20–39 years) [7, 31, 32] have shown that 7 days of a high sodium diet increases ROS which contribute to sodium-induced endothelial dysfunction by reducing the production and/or bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator. However, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated ROS formation following a single HSM. Acute consumption of an antioxidant (AO) cocktail containing vitamin C, E, and alpha-lipoic acid has been shown to lower free radical concentrations in venous blood from young healthy adults [33] and reverse endothelial dysfunction in older adults [34].

Given the likely role of ROS under high sodium conditions, the objective of this study was to determine the effect of an AO cocktail on the acute post-prandial effects of sodium on endothelial function, arterial stiffness, and wave reflection in young, healthy adults. Our primary hypothesis was that consumption of a HSM would reduce endothelial function, and increase arterial stiffness and wave reflection, while ingestion of an AO cocktail would mitigate these responses. Our secondary (exploratory) hypothesis was that vascular function would be reduced more in men than women and ingestion of an AO cocktail would exhibit greater benefits on vascular function in men than women.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study Population

The study protocol and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Delaware (ID# 841829) and conform to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Forty-one healthy adults between the ages of 18–45 participated in this study. Subjects were recruited through flyers posted around the University of Delaware campus and surrounding community, as well as through online advertisements. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to enrollment in the study. A flow diagram of subject enrollment in the study is presented in Figure 1. The study was not registered.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of subjects from eligibility criteria screening to study completion. FMD, flow-mediated dilation. *Per exclusion criteria, we excluded all subjects that were hypertensive according to the new BP guidelines (2017 ACC/AHA; published while recruitment was ongoing).

2.2. Experimental Protocol

2.2.1. Subject screening.

Subjects reported to the laboratory for a screening visit and completed a medical history form, Global Physical Activity Questionnaire [35], and a menstrual cycle history form (women only). Anthropometrics were collected and resting BP was taken after ≥10 min of seated rest (GE Medical Systems, Dash 2000, Milwaukee, WI) [36]. An average from three BP measurements was reported. Because the focus of this study was healthy adults, subjects with a history of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, renal impairment or use of heart or BP medications were excluded. Subjects with a BMI of 30kg/m2 or greater, highly trained endurance athletes or those who used tobacco products were also excluded. Finally, women were excluded if they were pregnant or breast-feeding.

2.2.2. Testing visits.

This was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study. Subjects came to the laboratory for two visits separated by at least 48 hours. Subjects taking AO supplements were asked to stop for the two weeks prior to testing. All women were tested in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Subjects arrived at the laboratory after having fasted for at least 6 hours, refrained from caffeine and alcohol for 12 hours, and not exercised for 24 hours. Both visits occurred at the same time of day. A 24-hour dietary recall was performed using the multiple-pass method [37] for the time leading up to the visits to determine if dietary intake was similar before both trials. Subjects were asked to replicate their dietary intake prior to both visits. Data were analyzed using Nutrient Data Systems for Research (NDSR, University of Minnesota).

2.2.3. Antioxidant cocktail and a high sodium meal (HSM).

Subjects received two doses of either an AO capsule containing 500 mg of Vitamin C, 300 IU of Vitamin E, and 300 mg of alpha-lipoic acid or a placebo capsule containing cellulose (Table 1). Both subject and researchers were blinded to the condition and the order of the visits was randomized. The AO cocktail dosage and timing was previously assessed for efficacy to reduce free radicals in blood [33]. The first dose was given after baseline (BSL) assessment of vascular function whereas the second dose was given 30 minutes after the first one and immediately prior to the HSM. The meal consisted of tomato soup with added salt for a total of 1,500 mg sodium (see Table 1 for nutrient breakdown). Subjects were instructed to consume the soup within 10 minutes. Vascular measurements were repeated at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes following soup consumption except brachial artery FMD that was measured at baseline, 60, and 120 minutes. In addition to vascular measures, peripheral BP was also assessed by oscillometric sphygmomanometry at each time point.

Table 1.

Nutrient content of experimental meal

| Nutrients/Contents | Amount | |

|---|---|---|

| High sodium meal | Energy | 120 kcal |

| Carbohydrates | 22 g | |

| Protein | 1 g | |

| Fat | 3 g | |

| Sodium | 1,445 mg | |

| Potassium | 250 mg | |

| Antioxidant cocktail | Vitamin C | 1,000 mg |

| Vitamin E | 600 IU | |

| Alpha-lipoic acid | 600 mg | |

| Placebo | 100% methyl cellulose | |

| Yellow food coloring (to mimic color of alpha-lipoic acid) | ||

2.3. Vascular Measures

2.3.1. Pulse wave analysis.

A central aortic pressure wave was synthesized from the measured brachial artery pressure wave with the SphygmoCor XCEL system (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia), which uses a transfer function and is FDA approved [38]. Central pressures and AIx were obtained from the synthesized wave. AIx is an index of wave reflection and is influenced by arterial stiffness. AIx is calculated as the ratio between augmented pressure and central pulse pressure, or AIx = (P2 – P1)/(Ps − Pd), where P1 is first shoulder of systolic pressure, P2 is second shoulder of systolic, Ps is peak systolic pressure, and Pd is end-diastolic pressure. Measures were performed in triplicate.

2.3.2. Pulse wave velocity (PWV).

Carotid-femoral PWV, a gold standard for assessing arterial stiffness [39], was measured using applanation tonometry and the Sphygmocor XCEL system (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) [38] while the subject was at rest in a supine position. Carotid and femoral pressure waveforms were recorded simultaneously using a high-fidelity strain-gauge transducer (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) placed over the carotid artery and a BP cuff placed on upper thigh, respectively. PWV distance was measured using the subtraction method where proximal distance (carotid measurement site to the sternal notch) was subtracted from distal distance (sternal notch to the thigh cuff). Carotid-femoral PWV was calculated by dividing the measured aortic distance (distal – proximal) by the average measured time delay between the initial upstrokes of corresponding carotid and femoral waveforms. Measures were performed in duplicate.

2.3.3. Brachial artery flow-mediate dilation (FMD).

FMD was assessed according to established guidelines [40]. Subjects were supine with the right arm extended and supported at heart level. A BP cuff was placed on the proximal forearm approximately 3 cm below the antecubital crease. Continuous longitudinal images of the brachial artery and continuous Doppler blood velocity were obtained using a 12-MHz linear phased array ultrasound transducer (Terason uSmart 3300, Teratech Corporation, Burlington, MA) after 20 minutes of supine rest. An adjustable mechanical arm was used to secure the transducer over the brachial artery. After baseline images and blood velocity were obtained, the cuff was rapidly inflated to 200mmHg for 5 minutes. Images and blood velocity were recorded throughout the 5-minute inflation period and continued for 2 minutes following cuff release in order to determine peak diameter change and calculation of shear rate. Brachial artery baseline and peak diameter were determined using the FMD Studio software (QUIPU, Pisa, Italy). FMD was expressed as a % change from baseline and Doppler blood velocity and diameter data were used to calculate shear rate area under the curve (AUC) from cuff deflation to peak diameter. Shear rate AUC has been shown to best represent the stimulus for dilation [41].

2.4. Blood Analyses

A venous blood sample was taken at the first experimental visit to assess hemoglobin (Hb 201+ model, HemoCue, Lake Forest, CA), hematocrit (Clay Adams Brand, Readacrit® Centrifuge, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and chloride) (EasyElectrolyte Analyzer, Medica, Bedford, MA), and plasma osmolality levels (Advanced 3D3 Osmometer, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA).

2.5. Statistical analyses

The primary outcome was the effect of the AO cocktail compared to PLA following a HSM on FMD. A priori power calculations indicated 40 subjects were necessary to detect a 1.3% change in FMD (90% power, p<0.05) (G*Power 3.1.9.4). The power calculation was based on findings from a similar study [42]. Paired sample t-tests were used to compare dietary intake and other variables at baseline between the two visits. A 2 × 2 × 5 mixed design ANOVA compared BP measures, PWV, and AIx. A 2 × 2 × 3 mixed design ANOVA compared FMD and FMD variables. The within-subject factors were time and treatment. To explore potential sex differences, sex was included as the between-subjects factor. Bonferroni adjustment was applied for post-hoc comparisons. Additionally, a general linear mixed model was used, which allowed for the inclusion of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) as time-varying covariates for PWV and AIx, respectively. The best fitting error covariance matrix was chosen by minimizing Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria. An independent t-test was used to compare subject characteristics, dietary intake, and FMD variables between men and women. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS, version 25.0, Chicago, IL). Significance was set a priori at p<0.05. Data is presented as means ± standard errors of the mean.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Subjects

Forty-one subjects completed the study (Table 2). Men and women were similar in age, were non-obese and were apparently healthy with a normal BP. Hemoglobin and hematocrit were lower in women but within normal ranges. Twenty four-hour dietary recalls were performed before both experimental visits and there were no differences in intake between the two visits (Table 3). Body mass did not change between the two study visits (AO: 69 ± 2 kg; PLA: 69 ± 2 kg; p=0.87).

Table 2.

Baseline subject characteristics

| All Subjects | Men | Women | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data | ||||

| N | 41 | 20 | 21 | |

| Ethnicity (H/NH)a | 1/30 | 0/15 | 1/15 | |

| Race (W/B/A)b | 31/2/5 | 14/1/5 | 17/1/0 | |

| Age (yr) | 24 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | 0.033* |

| Height (cm) | 172 ± 1 | 179 ± 1 | 166 ± 1 | <0.001* |

| Mass (kg) | 69 ± 2 | 78 ± 2 | 61 ± 2 | <0.001* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 0.4 | 24.3 ± 0.5 | 22.5 ± 0.5 | 0.013* |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 112 ± 1 | 116 ± 2 | 109 ± 1 | 0.002* |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 66 ± 1 | 65 ± 2 | 67 ± 2 | 0.383 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 81 ± 1 | 82 ± 1 | 81 ± 1 | 0.586 |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.9 ± 0.3 | 15.0 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.2 | <0.001* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.2 ± 0.7 | 45.7 ± 0.7 | 40.5 ± 0.9 | <0.001* |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 140.1 ± 0.4 | 140.5 ± 0.5 | 139.7 ± 0.6 | 0.346 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.687 |

| Serum chloride (mmol/L) | 103.9 ± 0.5 | 103.6 ± 0.8 | 104.3 ± 0.6 | 0.461 |

A, Asian; B, Black; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure;; H, Hispanic; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NH, non-Hispanic; W, White.

Values are means ± SEM.

Ten subjects (5 men/5 women) did not report ethnicity.

Three subjects (3 women) did not report race.

p<0.05 Men vs. Women

Table 3.

24-hour dietary intake prior to dietary trials

| All subjects (n=38) | Men (n=19) | Women (n=19) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | AO | PLA | AO | PLA | AO | |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 1,975 ± 109 | 1,887 ± 111 | 2,302 ± 155 | 2 122 ±167 | 1,647 ± 115* | 1,651 ± 129* |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 114 ± 5 | 111 ± 4 | 111 ± 8 | 107 ± 7 | 118 ± 6 | 114 ± 4 |

| Protein (g) | 46 ± 3 | 50± 3 | 50 ± 5 | 51 ± 4 | 43 ± 4 | 48 ± 3 |

| Fat (g) | 41 ± 2 | 42 ± 2 | 41 ± 3 | 43 ± 3 | 42 ± 2 | 41 ± 2 |

| Sodium (mg) | 1,792 ± 167 | 1,604 ± 104 | 1,674 ± 239 | 1,432 ± 125 | 1,909 ± 238 | 1,775 ± 160 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1,426 ± 77 | 1,417 ± 73 | 1,460 ± 109 | 1,430 ± 106 | 1,393 ± 113 | 1,405 ± 103 |

| Calcium (mg) | 471 ± 36 | 500 ± 34 | 424 ± 50 | 440 ± 49 | 519 ± 50 | 560 ± 43 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 190 ± 11 | 180 ± 30 | 187 ± 16 | 178 ± 13 | 193 ± 15 | 182 ± 16 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 39 ± 4 | 54 ± 10 | 39 ± 5 | 40 ± 8 | 39 ± 6 | 67 ± 17 |

| Vitamin E (IU) | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 |

Note: Nutrient intake is normalized per 1,000 kcal. AO, antioxidant; PLA, placebo. A single 24-hr recall is missing from 1 man and 2 women. Values are means ± SEM.

p<0.05 Men vs. Women.

3.2. Blood pressure

As shown in figure 2, systolic BP did not change while diastolic BP fluctuated across the time frame studied in both visits (60min: 67 ± 1; 120min: 69 ± 1 mmHg; time effect p=0.007). Similarly, MAP fluctuated in both visits due to changes in diastolic BP (60min: 79 ± 1; 120min: 81 ± 1 mmHg; time effect p=0.01). There were no differences in the BP response between sexes (systolic BP: time × treatment × sex p=0.11; diastolic BP: time × treatment × sex p=0.54; MAP: time × treatment × sex p=0.32). There were also no changes in HR nor pulse pressure (PP) throughout the course of the visits and between trials (HR: treatment × time interaction p=0.95; PP: treatment × time interaction p=0.36).

Figure 2.

Systolic (A) and diastolic (B) blood pressure (BP) response following a high sodium meal combined with either the antioxidant or placebo. Systolic BP did not change while diastolic BP increased from 60 to 120 min in both visits. Measurements were taken at baseline and every 30 minutes up to 2 hours after consumption of the soup. AO, antioxidant; BP, blood pressure; PLA, placebo. Values are means ± SEM. N=39; * p<0.05 vs. time 60.

3.3. Vascular Responses to High Sodium Meal

3.3.1. Pulse wave analysis and pulse wave velocity (PWV).

AIx adjusted for HR was greater at 60 min in the AO trial compared to PLA (AO: 0.7 ± 1.4, PLA: −1.7 ± 1.4%, time effect p<0.001) and was on average lower in the PLA trial (AO: 2.0 ± 1.3, PLA: 0.7 ± 1.3%, treatment effect p<0.01). However, there was no effect of sex (p=0.71), nor a treatment × time (p=0.31) or treatment × time × sex (p=0.33) interaction (Figure 3). Carotid-to-femoral PWV adjusted for MAP was significantly lower at 60 min compared to 30, 90, and 120 min in both trials demonstrating an effect of time (p=0.01) but no effect of treatment (p=0.12), and no treatment × time interaction (p=0.91). Although there was an effect of sex (p<0.01) with men having a higher PWV than women (men: 5.6 ± 0.1, women: 5.1 ± 0.1 m/s), there was no treatment × time × sex interaction (p=0.82) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Augmentation index (AIx) adjusted for heart rate following a high sodium meal with either the antioxidant (AO) or placebo (PLA). AIx was greater at 60 min in the AO trial compared to PLA. Measurements were taken at baseline and every 30 minutes up to 2 hours after consumption of the soup. AIx, augmentation index; AO, antioxidant; PLA, placebo. Values are means ± SEM. N=39 (2 subjects were missing a measurement); *p<0.05 vs. AO at time.

Figure 4.

Pulse wave velocity (PWV) adjusted for mean arterial pressure following a high sodium meal with either the antioxidant (AO) or placebo (PLA). PWV was lower at 60 min compared to 30, 90, and 120 min in both trials demonstrating an effect of time. Measurements were taken at baseline and every 30 minutes up to 2 hours after consumption of the soup. AO, antioxidant; PLA, placebo, PWV, pulse wave velocity. Values are means ± SEM. N=37 (4 subjects were missing a measurement). *p<0.05 vs. time 60.

3.3.2. Brachial artery flow-mediate dilation (FMD).

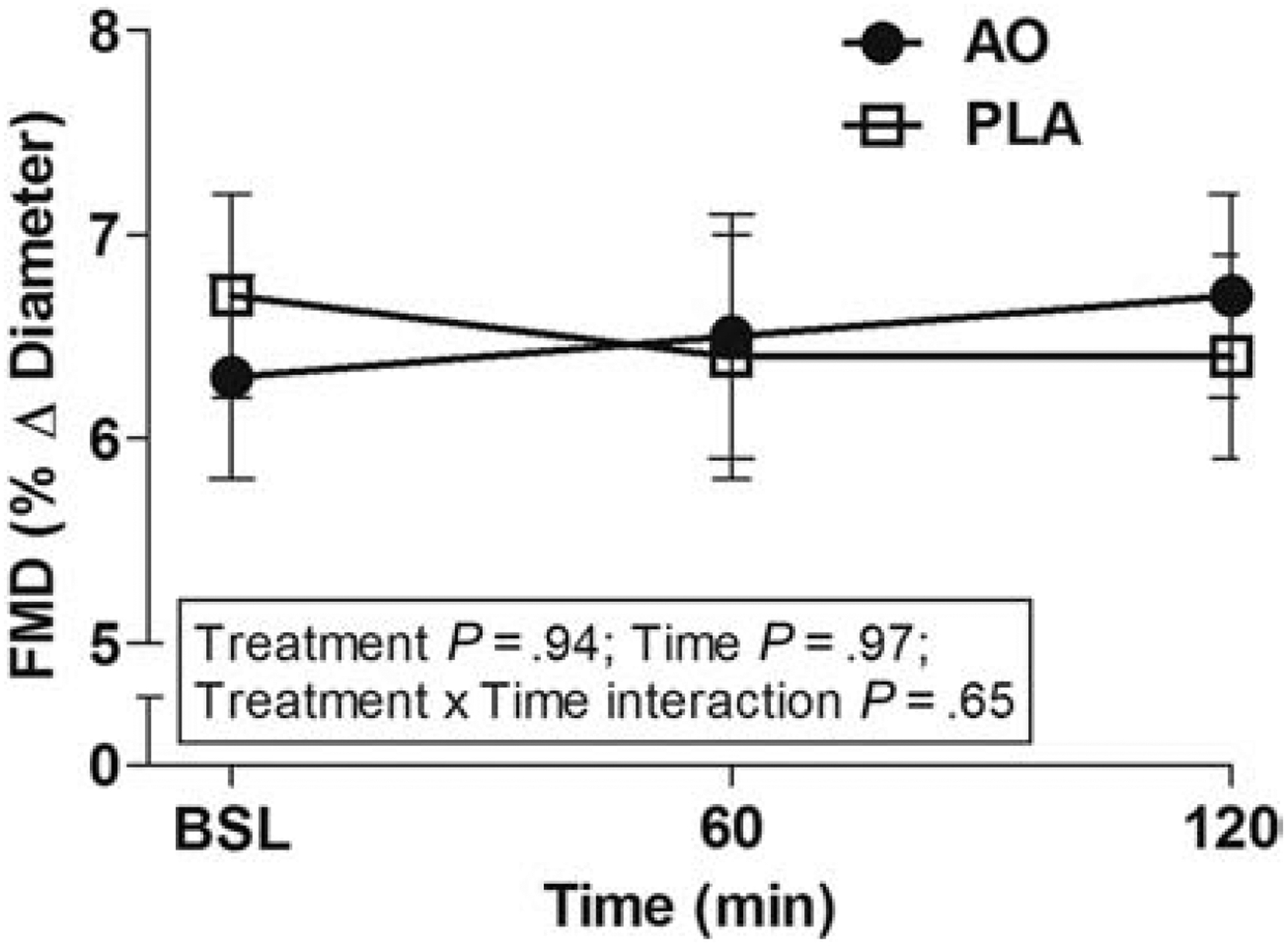

Baseline and peak brachial artery diameters did not differ between the two trials (Table 4). Shear rate AUC, an estimate for the shear stimulus for dilation, was not different between the two trials when all subjects were included (time effect p=0.70, treatment effect p=0.55, time × treatment interaction p=0.21, time × treatment × sex interaction p=0.29), however men had a reduced shear rate AUC following the HSM in both the PLA and AO treatments. Shear rate AUC was significantly greater in women at time 60 for both the PLA and AO trials and at time 120 for the AO trial compared to men (PLA 60min: 13,699±1,355 vs 19,548±1,711, p=0.01; AO 60min: 14,191±1,195 vs 19,957±2,059, p=0.02; AO 120min: 12,970±952 vs 18,567±1,720, p<0.01) (Table 4). Overall, there was no difference in the percent change in diameter for all subjects across time nor per trial, nor was there a treatment × time × sex interaction (p=0.08) (Data shown in Table 4 and Figure 5).

Table 4.

Vascular responses to a high sodium meal followed by the antioxidant cocktail/placebo.

| All subjects | Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | PLA | AO | PLA | AO | PLA | AO | |

| FMD diameter change (%) | BSL | 6.7±0.5 | 6.3±0.5 | 5.8±0.6 | 5.8±0.6 | 7.4±0.7* | 6.9±0.7 |

| 60min | 6.4±0.6 | 6.5±0.6 | 5.1±0.7 | 4.5±0.5 | 7.6±0.8* | 8.4±0.8* | |

| 120min | 6.4±0.5 | 6.7±0.5 | 4.8±0.6 | 6.2±0.6 | 7.9±0.6* | 7.2±0.8 | |

| Baseline diameter (mm) | BSL | 3.84±0.09 | 3.83± 0.12 | 4.26±0.11 | 4.22±0.11 | 3.43±0.08* | 3.46±0.16* |

| 60min | 3.81±0.10 | 3.79±0.10 | 4.31±0.11 | 4.26±0.10 | 3.33±0.06* | 3.35±0.07* | |

| 120min | 3.86±0.10 | 3.73±0.09 | 4.26±0.12 | 4.16±0.10 | 3.47±0.08* | 3.32±0.08* | |

| Peak diameter (mm) | BSL | 4.09 ±0.10 | 4.06±0.12 | 4.50±0.11 | 4.45±0.11 | 3.69±0.10* | 3.69±0.16* |

| 60 min | 4.04±0.10 | 4.02±0.09 | 4.52±0.11 | 4.45±0.10 | 3.58±0.07* | 3.61±0.07* | |

| 120min | 4.10±0.09 | 3.97±0.10 | 4.46±0.12 | 4.41±0.10 | 3.75±0.09* | 3.55±0.09* | |

| FMD (mm Δ) | BSL | 0.25±0.02 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.26±0.03 | 0.23±0.02 |

| 60min | 0.23±0.02 | 0.23±0.02 | 0.21±0.03 | 0.20±0.02 | 0.25±0.03 | 0.26±0.02 | |

| 120min | 0.24±0.02 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.20±0.02 | 0.25±0.02 | 0.27±0.02 | 0.24±0.03 | |

| Shear rate (AUC) | BSL | 16,498±976 | 17,794±1,382 | 15,552±1,168 | 16,167±1,380 | 17,399±1,550 | 19,344±2,342 |

| 60min | 16,695±1,179 | 17,144±1,274 | 13,699±1,355 | 14,191±1,195 | 19,548±1,711* | 19,957±2,059* | |

| 120min | 16,276±1,316 | 15,837±1,079 | 14,394±1,664 | 12,970±952 | 18,067±1,982 | 18,567±1,720* | |

Values are means ± SEM.

p<0.05 Men vs. Women.

AO, antioxidant; AUC, area under the curve; BSL, baseline; PLA, placebo.

Figure 5.

Endothelial function in response to a high sodium meal combined with either the antioxidant (AO) or placebo (PLA) as assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD). There was no difference in endothelial function for all subjects across time, treatment, nor there was a treatment × time × sex interaction (p=0.08). Measurements were taken at baseline, 60 and 120 minutes following consumption of the soup. AO, antioxidant; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; PLA, placebo. Values are means ± SEM. N=41.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study sought to determine the acute role of an oral AO cocktail on attenuating the post-prandial effects of a HSM on the vasculature in young healthy adults. The major finding of this study is that an acute HSM did not negatively affect FMD, hemodynamics, arterial stiffness, nor wave reflection during the 2-hour postprandial state, thus the AO cocktail was not needed to improve these indices of vascular function. We also found no sex differences in the vascular response to the meal and AO cocktail. Hence, we reject both our primary and secondary (exploratory) hypotheses. These findings suggest that overall, young healthy adults can effectively buffer the effects of an acute HSM on their vasculature. While young healthy adults in their mid-twenties may not suffer adverse effects from excess sodium on the vasculature acutely, prolonged intake of a high sodium diet has been shown to be detrimental even in young adults of similar age [32], as well as in middle-aged adults [6, 7, 10, 19]. Thus developing dietary habits that include lowering sodium consumption are beneficial for lifelong health [43].

High sodium consumption continues to remain a major public health concern as U.S. adults consume 150% of the recommended intake [4, 5]. It is not uncommon for sodium levels in a single meal in fast food, fast-casual, and casual restaurants to exceed the recommended daily sodium intake [44, 45]. This is alarming as a high sodium intake is a risk factor for hypertension and other forms of cardiovascular disease [46, 47]. While sodium has been strongly associated with increased BP, it is now known to have negative consequences for the endothelium that occur independent of changes in BP even in healthy young adults [6, 8, 10]. This is important as endothelial dysfunction is thought to precede the development of cardiovascular disease and is considered a non-traditional risk factor for pre-clinical conditions such as atherosclerosis and hypertension [48, 49]. The mechanism behind the deleterious effects of sodium on the vasculature is not completely known but increases in ROS have been implicated [7, 31]. While these effects have been studied in the context of chronic sodium consumption and in subjects of a wide age range, the acute effects of sodium in young adults have received less attention.

In this study, we demonstrated that a HSM had little negative consequences on hemodynamics, arterial stiffness, and wave reflection as evidenced by time-dependent effects that were independent of treatment (PLA or AO). While diastolic BP fluctuated during the trial, there were no hemodynamic differences between trials which is comparable to other published work [25, 26]. AIx, an index of wave reflection, was lower than reported in studies looking at the acute effects of sodium [26, 42] likely highlighting the younger age of our subjects. Despite this, we found a reduction in AIx following consumption of HSM with no treatment × time interaction, which is similar to the study by Blanch and colleagues [42]. A reduction in AIx after consumption of a heavier mixed meal (i.e. a meal that contains greater amount of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) was observed in other studies investigating the postprandial state, regardless of the sodium and macronutrient content of the meal [50–52]. This indicates that a reduction in AIx may be independent of sodium and due to physiological changes such as blood flow or hormonal changes during digestion and absorption. A reduction in AIx was attributed to increased splanchnic blood flow [53] and/or insulin-mediated vasodilation [52] following meal consumption. We observed smaller reductions in AIx than in the study by Taylor et al. [50] and Greenfield et al. [52] as the HSM was lighter (i.e. energy and carbohydrate content of the meal was lower; see Table 1). This is consistent with the results of Greenfield et al. [52] as the meal with higher carbohydrate content resulted in an AIx reduction of greater magnitude compared to a low carbohydrate meal [52].

PWV fluctuated over the two hours postprandial but was not impacted by trial, as seen in other acute studies [42]. Men in our cohort had higher PWV values than women, but this sex difference did not influence the response to the HSM nor the AO cocktail. Sex differences in PWV are reported in the literature and greater values in men are attributed to lower levels of estrogen and higher levels of the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 as compared to women [54, 55]. Similar to our findings, we previously reported that a high sodium diet lasting 7 days did not increase PWV in young adults (average age 27 years) [19]. Changes in PWV generally reflect structural remodeling of arteries, therefore it was unlikely that we would observe significant changes as remodeling occurs over long periods of time (i.e. years) [56]. However, it is important to note that PWV may be influenced by sympathetic nervous system activity which has been assessed by muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) [57]. Taylor and colleagues demonstrated MSNA increased 45–60 min following consumption of a mixed meal while PWV slightly decreased at 60 min [50]. We also observed a slight drop in PWV at 60 min which is in agreement with their findings. Altogether, it appears that our findings regarding wave reflection and arterial stiffness could be attributed to the meal itself and the postprandial state rather than the specific effect of sodium or the AO cocktail.

Reduced endothelial function utilizing brachial artery FMD in response to a HSM has been previously reported. Dickinson et al. [25] found that an acute meal containing 1,500 mg of sodium reduced endothelial function more than a low sodium meal at both 30 and 60 minutes following consumption. Furthermore, Blanch et al. [42] showed that a HSM reduced FMD compared to a HSM containing high potassium highlighting a role of potassium in attenuating the effects of sodium. Contrary to these findings, we did not see a reduction in postprandial FMD. Our subjects were younger (average age 24 years) than in both the Dickinson [25] (average age 37 years) and Blanch [42] (average age 37 years) studies. FMD results in those studies may be influenced by the wide age range (18–70 years) as FMD declines with age [28]. Further, it may be that our younger cohort more effectively buffered the effects of the HSM due to oxidative eustress which also diminishes with age [58].

In our study, we sought to determine if an AO cocktail could attenuate the negative effects of sodium on the vasculature given the elevated oxidative stress in adults (mean ages 20–39 years) following 7 days of high sodium consumption seen in previous work [7, 31, 32]. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have investigated ROS formation following a single HSM. Components of the cocktail were the non-enzymatic AOs vitamin C (ascorbic acid), vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid, which have distinct AO functions. Vitamin C is a potent, non-specific scavenger of free radicals, vitamin E is a lipid peroxyl radical scavenger and is regenerated by vitamin C [59], whereas alpha-lipoic acid regenerates both vitamin C and vitamin E [60]. This AO cocktail has successfully been used by others in young healthy men [33], the elderly [34], and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [61]. While this AO cocktail has successfully improved FMD acutely in older adults, it was not beneficial for young healthy subjects as it reduced FMD in that population [34]. These data, along with others [62], suggest that a certain level of free radicals is beneficial in the circulation. Indeed, free radicals promote endogenous AO enzymes which upregulate AO capacity [58, 63]. However, vascular function was not impaired in our study population suggesting endogenous AOs were able to buffer any increase in oxidative stress presented by the HSM therefore rendering the AO cocktail unnecessary in this young healthy group.

We have previously shown that men have a more deleterious response to chronic sodium loading than women as their FMD declined more after 7 days of a high sodium diet [8]. This is supported by a study in young healthy adults in which men demonstrated a greater sensitivity to 5 days of sodium loading as evidenced by a reduction in the NO-component of acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in the forearm [64]. Thus, in this study we assessed the role of sex on the effects of an acute HSM on vascular function as an exploratory aim. However, our data suggest that there are no sex differences in vascular function in response to a HSM and AO supplementation, indicating young men and women can successfully buffer the effect of acutely administered HSM on the vasculature. Nevertheless, our FMD results trended to be significant (treatment × time × sex interaction p=0.08) and further research is warranted.

This study has a few limitations. First, while we performed a comprehensive assessment of vascular function in our study, we did not measure free radical concentrations in the blood following meal consumption. Although chronic studies confirm increases in oxidative stress following a high sodium diet [7, 31, 32], there are no studies that have quantified oxidative stress after a single HSM. Second, we did not verify changes in vitamin C, E, or alpha-lipoic acid levels post-cocktail consumption. However, this AO cocktail has been used successfully in other studies and has reduced free radical concentration [33], and increased serum vitamin C levels and AO capacity in young adults in an acute setting [33, 34]. Third, although we did not measure serum sodium following soup consumption, meals with equal amounts of sodium were successfully used by other groups and have showed a postprandial increase in serum sodium [26, 42, 65]. Fourth, we did not assess endothelium-independent effects however in previous work we have demonstrated that the effects of sodium are specific to the endothelium and not smooth muscle [6]. Fifth, we used 24-hour dietary recalls to assess subjects’ dietary sodium intake prior to both visits. We acknowledge 24-hr sodium urinary excretion would be a more accurate method.

In conclusion, we found that an acute HSM did not exhibit deleterious effects on the vasculature of our cohort of young healthy adults. Endothelial function remained unchanged, while arterial stiffness and wave reflection were likely reduced due to the postprandial state. Consequently, administration of the AO cocktail was not necessary as there was no vascular impairments to be rescued, as initially hypothesized. In summary, while young healthy adults may not suffer acute adverse effects from excess sodium, adoption of a lower sodium diet may be beneficial for long term health as adverse effects of sodium on the cardiovascular system are pronounced with aging [43].

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Center of Biomedical Research Excellence from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [P20GM113125]. The sponsor had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data nor in the writing of this manuscript or decision to publish. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIx

augmentation index

- AO

antioxidant

- AUC

area under the curve

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- BSL

baseline

- DGA

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

- FMD

flow-mediated dilation

- HR

heart rate

- HSM

high sodium meal

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MSNA

muscle sympathetic nerve activity

- NO

nitric oxide

- PLA

placebo

- PWV

pulse wave velocity

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LIST OF REFERENCES

- [1].Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013;346:f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Collaborators GBDD. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition ed2015. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brouillard AM, Kraja AT, Rich MW. Trends in Dietary Sodium Intake in the United States and the Impact of USDA Guidelines: NHANES 1999–2016. Am J Med 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].DuPont JJ, Greaney JL, Wenner MM, Lennon-Edwards SL, Sanders PW, Farquhar WB, et al. High dietary sodium intake impairs endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy salt-resistant humans. J Hypertens 2013;31:530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Greaney JL, DuPont JJ, Lennon-Edwards SL, Sanders PW, Edwards DG, Farquhar WB. Dietary sodium loading impairs microvascular function independent of blood pressure in humans: role of oxidative stress. J Physiol 2012;590:5519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lennon-Edwards S, Ramick MG, Matthews EL, Brian MS, Farquhar WB, Edwards DG. Salt loading has a more deleterious effect on flow-mediated dilation in salt-resistant men than women. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:990–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tzemos N, Lim PO, Wong S, Struthers AD, MacDonald TM. Adverse cardiovascular effects of acute salt loading in young normotensive individuals. Hypertension 2008;51:1525–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Matthews EL, Brian MS, Ramick MG, Lennon-Edwards S, Edwards DG, Farquhar WB. High dietary sodium reduces brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in humans with salt-sensitive and salt-resistant blood pressure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015;118:1510–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction: a marker of atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Higashi Y, Noma K, Yoshizumi M, Kihara Y. Endothelial function and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Circ J 2009;73:411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O’Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Baldo MP, Brant LCC, Cunha RS, Molina M, Griep RH, Barreto SM, et al. The association between salt intake and arterial stiffness is influenced by a sex-specific mediating effect through blood pressure in normotensive adults: The ELSA-Brasil study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21:1771–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Polonia J, Monteiro J, Almeida J, Silva JA, Bertoquini S. High salt intake is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events: a 7.2-year evaluation of a cohort of hypertensive patients. Blood Press Monit 2016;21:301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].D’Elia L, Galletti F, La Fata E, Sabino P, Strazzullo P. Effect of dietary sodium restriction on arterial stiffness: systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2018;36:734–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Starmans-Kool MJ, Stanton AV, Xu YY, Mc GTSA, Parker KH, Hughes AD. High dietary salt intake increases carotid blood pressure and wave reflection in normotensive healthy young men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110:468–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Muth BJ, Brian MS, Chirinos JA, Lennon SL, Farquhar WB, Edwards DG. Central systolic blood pressure and aortic stiffness response to dietary sodium in young and middle-aged adults. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017;11:627–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. Effect of a single high-fat meal on endothelial function in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Plotnick GD, Corretti MC, Vogel RA. Effect of antioxidant vitamins on the transient impairment of endothelium-dependent brachial artery vasoactivity following a single high-fat meal. JAMA 1997;278:1682–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Patik JC, Tucker WJ, Curtis BM, Nelson MD, Nasirian A, Park S, et al. Fast-food meal reduces peripheral artery endothelial function but not cerebral vascular hypercapnic reactivity in healthy young men. Physiol Rep 2018;6:e13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mah E, Noh SK, Ballard KD, Matos ME, Volek JS, Bruno RS. Postprandial hyperglycemia impairs vascular endothelial function in healthy men by inducing lipid peroxidation and increasing asymmetric dimethylarginine:arginine. J Nutr 2011;141:1961–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beckman JA, Goldfine AB, Gordon MB, Creager MA. Ascorbate restores endothelium-dependent vasodilation impaired by acute hyperglycemia in humans. Circulation 2001;103:1618–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dickinson KM, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. Endothelial function is impaired after a high-salt meal in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dickinson KM, Clifton PM, Burrell LM, Barrett PH, Keogh JB. Postprandial effects of a high salt meal on serum sodium, arterial stiffness, markers of nitric oxide production and markers of endothelial function. Atherosclerosis 2014;232:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McEniery CM, Yasmin Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR, et al. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Spiegelhalter DJ, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Aging is associated with endothelial dysfunction in healthy men years before the age-related decline in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24:471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lenda DM, Boegehold MA. Effect of a high-salt diet on oxidant enzyme activity in skeletal muscle microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lenda DM, Sauls BA, Boegehold MA. Reactive oxygen species may contribute to reduced endothelium-dependent dilation in rats fed high salt. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000;279:H7–H14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ramick MG, Brian MS, Matthews EL, Patik JC, Seals DR, Lennon SL, et al. Apocynin and Tempol ameliorate dietary sodium-induced declines in cutaneous microvascular function in salt-resistant humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;317:H97–H103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Baric L, Drenjancevic I, Mihalj M, Matic A, Stupin M, Kolar L, et al. Enhanced Antioxidative Defense by Vitamins C and E Consumption Prevents 7-Day High-Salt Diet-Induced Microvascular Endothelial Function Impairment in Young Healthy Individuals. J Clin Med 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Richardson RS, Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Lawrenson L, Nishiyama S, et al. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H1516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wray DW, Nishiyama SK, Harris RA, Zhao J, McDaniel J, Fjeldstad AS, et al. Acute reversal of endothelial dysfunction in the elderly after antioxidant consumption. Hypertension 2012;59:818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chu AH, Ng SH, Koh D, Muller-Riemenschneider F. Reliability and Validity of the Self- and Interviewer-Administered Versions of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). PLoS One 2015;10:e0136944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:e127–e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:1140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Butlin M, Qasem A. Large Artery Stiffness Assessment Using SphygmoCor Technology. Pulse (Basel) 2017;4:180–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, et al. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens 2012;30:445–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thijssen DHJ, Bruno RM, van Mil A, Holder SM, Faita F, Greyling A, et al. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2534–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Thijssen DH, Bullens LM, van Bemmel MM, Dawson EA, Hopkins N, Tinken TM, et al. Does arterial shear explain the magnitude of flow-mediated dilation?: a comparison between young and older humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;296:H57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Blanch N, Clifton PM, Petersen KS, Keogh JB. Effect of sodium and potassium supplementation on vascular and endothelial function: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Auchincloss AH, Leonberg BL, Glanz K, Bellitz S, Ricchezza A, Jervis A. Nutritional value of meals at full-service restaurant chains. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014;46:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vercammen KA, Frelier JM, Moran AJ, Dunn CG, Musicus AA, Wolfson JA, et al. Calorie and Nutrient Profile of Combination Meals at U.S. Fast Food and Fast Casual Restaurants. Am J Prev Med 2019;57:e77–e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, Markandu ND, Anand V, Dalton RN, et al. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension 2009;54:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, et al. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Luscher TF, Tanner FC, Tschudi MR, Noll G. Endothelial dysfunction in coronary artery disease. Annu Rev Med 1993;44:395–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Taylor JL, Curry TB, Matzek LJ, Joyner MJ, Casey DP. Acute effects of a mixed meal on arterial stiffness and central hemodynamics in healthy adults. Am J Hypertens 2014;27:331–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ahuja KD, Robertson IK, Ball MJ. Acute effects of food on postprandial blood pressure and measures of arterial stiffness in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Greenfield JR, Samaras K, Chisholm DJ, Campbell LV. Effect of postprandial insulinemia and insulin resistance on measurement of arterial stiffness (augmentation index). Int J Cardiol 2007;114:50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Jager K, Bollinger A, Valli C, Ammann R. Measurement of mesenteric blood flow by duplex scanning. J Vasc Surg 1986;3:462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Doonan RJ, Mutter A, Egiziano G, Gomez YH, Daskalopoulou SS. Differences in arterial stiffness at rest and after acute exercise between young men and women. Hypertens Res 2013;36:226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Waddell TK, Dart AM, Gatzka CD, Cameron JD, Kingwell BA. Women exhibit a greater age-related increase in proximal aortic stiffness than men. J Hypertens 2001;19:2205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 2003;107:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Holwerda SW, Luehrs RE, DuBose L, Collins MT, Wooldridge NA, Stroud AK, et al. Elevated Muscle Sympathetic Nerve Activity Contributes to Central Artery Stiffness in Young and Middle-Age/Older Adults. Hypertension 2019;73:1025–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Jones DP, Mody VC Jr., Carlson JL, Lynn MJ, Sternberg P Jr. Redox analysis of human plasma allows separation of pro-oxidant events of aging from decline in antioxidant defenses. Free Radic Biol Med 2002;33:1290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Machlin LJ, Bendich A. Free radical tissue damage: protective role of antioxidant nutrients. FASEB J 1987;1:441–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tibullo D, Li Volti G, Giallongo C, Grasso S, Tomassoni D, Anfuso CD, et al. Biochemical and clinical relevance of alpha lipoic acid: antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, molecular pathways and therapeutic potential. Inflamm Res 2017;66:947–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Rossman MJ, Groot HJ, Reese V, Zhao J, Amann M, Richardson RS. Oxidative stress and COPD: the effect of oral antioxidants on skeletal muscle fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45:1235–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Liu Y, Zhao H, Li H, Kalyanaraman B, Nicolosi AC, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial sources of H2O2 generation play a key role in flow-mediated dilation in human coronary resistance arteries. Circ Res 2003;93:573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ristow M, Zarse K, Oberbach A, Kloting N, Birringer M, Kiehntopf M, et al. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:8665–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Eisenach JH, Gullixson LR, Kost SL, Joyner MJ, Turner ST, Nicholson WT. Sex differences in salt sensitivity to nitric oxide dependent vasodilation in healthy young adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;112:1049–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Migdal KU, Robinson AT, Watso JC, Babcock MC, Serrador JM, Farquhar WB. A high-salt meal does not augment blood pressure responses during maximal exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2020;45:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]