Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the factors associated with whether assisted living communities (ALCs) in Florida evacuated or sheltered in place for Hurricane Irma in 2017, focusing on license type as a proxy for acuity of care.

Design:

Cross-sectional study using data collected by the state through its emergency reporting system and a post-hurricane survey.

Setting and Participants:

Analyses included all 3,112 ALCs in the emergency reporting system. A subset of 1,880 that completed the survey provided supplementary data.

Methods:

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between ALC characteristics - license type, size, payment, profit status, rural location, geographical region, and being under an evacuation order – and whether they evacuated. Logistic regression was used to test associations between characteristics and evacuation status.

Results:

Of 3,112 ALCs, 560 evacuated, 2,552 sheltered in place. Bivariate analysis found significant associations between evacuation status and evacuation order, license type (mental health care), payment, and region. In the adjusted analysis, medium and larger ALCs were 43% (p<.001) and 53% (p<.001) less likely to evacuate than ALCs with fewer than 25 beds. Compared to ALCs in the Southeast, nearly every region was more likely to evacuate, with the highest likelihood in the Central West (odds ratio 1.76, 95% confidence interval 1.35–2.30). ALCs under an evacuation order were 8 times more likely to evacuate (p<.001). We found no relationship between evacuation status and having a license to provide higher care.

Conclusions and Implications:

Prior research highlighting harm associated with evacuation has led to recommendations that LTC facilities carefully consider resident impairment in evacuation decision-making. Evidence that small ALCs are more likely to evacuate and that having a higher-care license is not associated with evacuation likelihood shows research is needed to understand how ALCs weigh resident risks in decisions to evacuate or shelter in place.

Keywords: Assisted Living, Disaster Response, Evacuation

Brief Summary:

Despite prior work on the risks of evacuating nursing home residents in natural disasters, assisted living communities serving more impaired residents chose evacuation over sheltering in place in response to Hurricane Irma in 2017.

Residents of long-term care (LTC) are especially vulnerable to harm in natural disasters.1 Research in this area has focused largely on nursing homes (NHs).2 Dosa and colleagues examined NHs affected by Gulf Coast hurricanes in 2005 and 2008, addressing the complexity of the decision to evacuate or shelter in place. They found all residents were at greater risk during the hurricanes, however, the act of evacuation compounded morbidity and mortality.3 Laditka et al and others have reported on the difficulties of transporting and providing care to evacuees in sheltering NHs.4, 5 Thomas and colleagues found that post-hurricane hospitalizations increased for the most functionally impaired residents who were evacuated,6 and Brown and colleagues documented the deleterious effects on NH residents with dementia.7 Policy recommendations have emphasized that multiple factors should be considered in a facility’s decision to evacuate, including the effect on frail residents.2, 8, 9

Assisted living communities (ALCs) make up a large segment of LTC. However, little is known about ALC disaster preparedness and response, a concern given that of an estimated 811,000 ALC residents in the US in 2016, 34% had been diagnosed with heart disease, 42% with dementia, and 56% needed help with walking.10 A study of Texas ALCs and NHs (N=217) found a majority evacuated for Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 and that resident death was associated with evacuation.11 Brown and colleagues 12 surveyed personnel of 143 Florida ALCs affected by hurricanes in 2004–05, reporting they experienced the same problems as NHs and struggled with evacuation decisions. A U.S. Senate committee reported on a number of preparedness lapses among ALCs after Hurricane Harvey in Texas in 2017, including residents left in flooded buildings and one resident left in her room while others from her ALCs were relocated.13 Florida has 3,100 ALCs servicing 85,000 residents, with 1,462 licensed to serve those with higher physical, cognitive, and/or mental health needs. Florida law requires all ALCs to develop disaster plans, but the requirements are not as prescriptive or well-developed as the federal rules for NHs.8

On Sept. 10, 2017, Hurricane Irma made landfall in Southwest Florida as a Category 3 hurricane. Its track and predicted strength at landfall had been uncertain, prompting evacuations across the state.14, 15 The goal of this research was to examine Florida ALCs to test the association between having a license to serve residents with greater care needs and the decision to evacuate or shelter in place during Hurricane Irma.

Methods

Our data include all ALCs in Florida during Hurricane Irma. All were used because of the broad threat posed by the storm, with initial predictions suggesting an eastward approach on Florida with subsequent movement of the track toward the west. We combined data from the FLHealthStat reporting system and Hurricane Irma Facility Impact (HIFI) survey. FLHealthStat was an online emergency reporting system for all health care providers. State law required ALC administrators or owners to report key data (e.g. contact information, evacuation status) immediately before and after the hurricane. The state emergency operations center used these data to monitor providers’ operations at the time of the hurricane and respond to emergency needs in the days after the hurricane. The HIFI survey was a voluntary survey emailed by the state Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) to all ALC owners/administrators between October 25th and November 2nd, 2017, to gain additional information for future disaster preparation. It contained 23 questions (e.g., whether and when the ALC evacuated, disaster plan problems). Of the 3,112 ALCs in the FLHealthStat data, 1,888 (60.7%) completed the HIFI survey.

In the present study evacuation was defined as leaving the ALC before Hurricane Irma made landfall on Sept. 10 or up to 12 days after, when the FLHealthStat system closed its data collection for that storm. To determine whether an ALC evacuated or sheltered in place we used responses provided to both the FLHealthStat and the HIFI survey. FLHealthStat served as the basis for determining evacuation status. However, comparison of the two datasets showed that 246 (13%) of the 1,888 HIFI survey responses on evacuation status differed from what was reported to FLHealthStat. In these cases we used the HIFI evacuation status data because the FLHealthStat data were collected largely amid the confusion of hurricane preparations, while the HIFI survey data were collected six weeks after the hurricane, under more stable, non-crisis circumstances.

Florida ALC data (e.g. license, payment type) were obtained from AHCA. We used licensure status as a proxy for determining residents acuity. Florida has four ALC license types. All have a standard license. An Extended Congregate Care (ECC) license enables ALCs to provide residents with limited nursing and ADL assistance; ALCs with a Limited Nursing Services (LNS) license provide licensed nursing services; and ALCs with a Limited Mental Health (LMH) license serve residents with mental health diagnoses.(16) We combined ECC and LNS into one group because both serve residents with greater physical and cognitive dependency – reported in prior literature as “high-frailty.”16 Given the nature of mental health needs, LMH remained as a single group. An LMH-licensed residence with an extended care and/or limited nursing services license remained in the LMH category.

Other variables potentially associated with decisions to evacuate or shelter in place were examined. They were ALC size, small (<25 beds), medium (25–100 beds), or large (>100 beds); acceptance of assistance for low-income residents (Optional State Supplementation [OSS]) and acceptance of Medicaid (yes/no); profit status (for-profit or not-for-profit); rural (or urban) area, based on Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services rural ZIP codes; and geographic region (Southeast, Southwest, Central East, Central West, Northeast, or Northwest).

Additionally we examined whether the ALC was in an area under a mandatory evacuation order for Hurricane Irma. We mapped each ALC’s location using ArcGIS mapping software (ESRI, Redlands, CA) and determined each location’s evacuation zone. Zones are typically designated with letters A-F to indicate an area’s level of storm surge/flooding risk.17,18 As a hurricane approaches, county emergency management officials determine and publicly announce which zones are being designated for mandatory evacuation. “Mandatory” signifies that officials perceive a risk of dangerous storm surge in an area, to the extent that emergency services will be unavailable to those who remain. We used publicly available emergency advisories naming zones and areas (e.g., barrier islands) mandated to evacuate as Hurricane Irma approached. We then divided ALCs into those ordered or not ordered to evacuate (i.e., those in zones under mandatory evacuation orders and those in zones not under such orders).

We performed chi-square tests of independence to determine mean unadjusted differences in ALC characteristics and evacuation status, with values of p < .05 considered significant. We performed post-hoc analysis of ALC size, license group and geographic region with Bonferroni adjustments to determine significant group differences. We next conducted multivariable logistic regression with evacuation status (evacuated vs. sheltered in place) as the dependent variable. Independent variables comprised those significantly associated with evacuation status in the bivariate analyses, as well as ALC size, based on previous research.11 Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL)

Results

Of the 3,112 ALCs in Florida during Hurricane Irma, 13.1% were under evacuation orders. A higher percentage evacuated, with 18.0% (n=560) relocating their residents and 82.0% (n=2,552) sheltering in place (see Table 1.) Of the total ALCs, 69.5% were small, 20.5% were medium-sized, and 10.0% were large. Nearly 23% had an extended care and/or limited nursing license and 24.5% had a mental health license. Less than half accepted state supplemental payments or Medicaid; nearly all were for-profit or urban.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Assisted Living Communities, by Evacuation Status before and after Hurricane Irma (N = 3,112)

| Total (N=3,112) N (%) |

Evacuated (n=560) n (%) |

Sheltered in Place (n=2,552) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evacuation Order | p < .001 | |||

| Ordered to Evacuate | 408 (13.1) | 212 (51.9) | 196 (48.0) | |

| No Order to Evacuate | 2,704 (86.9) | 348 (12.9) | 2,356 (87.1) | |

| ALC Size | p = .31 | |||

| Small (<26 beds) | 2,164 (69.5) | 402 (18.7) | 1,760 (81.3) | |

| Medium (26–100 beds) | 637 (20.5) | 107 (16.8) | 530 (83.2) | |

| Large (>100 beds) | 311 (10.0) | 49 (15.8) | 262 (84.2) | |

| License Type | p = .06 | |||

| Standard | 1,650 (53.0) | 305 (18.5) | 1,345 (81.5) | |

| ECC/LNS | 701 (22.5) | 139 (19.8) | 562 (80.2) | |

| LMH | 761 (24.5) | 116 (15.2) | 645 (84.7) | |

| Medicaid | p = .58 | |||

| Accepts Medicaid | 1,344 (43.2) | 236 (17.5) | 1,108 (82.4) | |

| Does not accept | 1,768 (56.8) | 324 (18.3) | 1,444 (81.7) | |

| OSS | p < .001 | |||

| Accepts OSS | 1,204 (38.7) | 178 (14.7) | 1,026 (85.2) | |

| Does not accept | 1,908 (61.3) | 382 (20.0) | 1,526 (80.0) | |

| Profit Status | p = .33 | |||

| For-Profit | 2,923 (93.9) | 521 (17.8) | 2,402 (82.2) | |

| Not-For-Profit | 189 (6.1) | 39 (20.6) | 150 (79.4) | |

| Rural Area | p = .54 | |||

| Rural | 66 (2.1) | 10 (15.2) | 56 (84.8) | |

| Urban | 3,046 (97.9) | 550 (18.1) | 2,496 (81.9) | |

| Region | p < .001 | |||

| Southeast | 1,342 (43.1) | 193 (14.4) | 1,149 (85.6) | |

| Southwest | 115 (3.7) | 48 (41.7) | 67 (58.3) | |

| Central East | 446 (14.3) | 82 (18.4) | 364 (81.6) | |

| Central West | 779 (25.0) | 167 (21.4) | 612 (78.6) | |

| Northeast | 259 (8.3) | 56 (21.6) | 203 (78.4) | |

| Northwest | 171 (5.5) | 14 (8.2) | 157 (91.8) |

Note. Row percentages are presented

ECC = Extended Congregate Care, LNS = Limited Nursing Services, LMH = Limited Mental Health, OSS = Optional State Supplementation.

Being under a mandatory evacuation order was associated with a greater likelihood of evacuating (p < .001) in the unadjusted analysis. License type, overall, approached significance (p=.06), with post-hoc tests showing that mental health-licensed ALCs were less likely to evacuate, at p <.05. In addition, ALCs that accepted state supplemental payments were less likely to evacuate (p < .001). We also observed statistically significant differences in evacuation status by region (p <.001): higher proportions of ALCs in the Southwest and Central West regions evacuated for the storm; lower proportions of ALCs in the Southeast evacuated.

In adjusted analyses, evacuation order, ALC size, payment type, and region were significantly associated with evacuation status (see Table 2). There were no significant associations between evacuation and having a license to provide higher care.

Table 2.

Odds Ratio of Evacuation by ALC Characteristic (N= 3,112)

| VARIABLES | Odds Ratio | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evacuation Order (Ref: Not Ordered) | |||

| Ordered*** | 8.06 | <.001 | [6.28–10.34] |

| Size [Ref: Small (> 25 beds)] | |||

| Medium (25–100 beds)*** | .546 | <.001 | [0.41 – 0.73] |

| Large (101+ beds)*** | .431 | <.001 | [0.29 – 0.64] |

| Bed Type (Ref: No OSS Beds) | |||

| OSS Beds** | .695 | .008 | [0.53 – 0.91] |

| License (Ref: Standard) | |||

| ECC/LNH | 1.08 | .56 | [0.82 – 1.43] |

| LMH | .953 | .74 | [0.71 – 1.27] |

| Region (Ref: Southeast) | |||

| Southwest | 1.58 | 07 | [0.97 – 2.58] |

| Central East* | 1.43 | .032 | [1.03 – 1.98] |

| Central West*** | 1.76 | <.001 | [1.35 – 2.30] |

| Northeast** | 1.65 | .009 | [1.13 – 2.39] |

| Northwest | .952 | .87 | [0.53 – 1.73] |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Note. OSS = Optional State Supplementation, ECC = Extended Congregate Care, LNS = Limited Nursing Services, LMH = Limited Mental Health

Discussion

This study examined the decision to evacuate among ALCs affected by Hurricane Irma in 2017. The 18% that evacuated were home to approximately 14,000 residents. Prior research has found that evacuation (vs. sheltering in place) poses risks to LTC residents, particularly those with greater impairments. 3, 6,19 Nevertheless, our results showed there were no differences in the likelihood to evacuate according to type of population served, including severity of need.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine ALCs across a state affected by a major hurricane. All ALCs in Florida are state regulated and required to have disaster plans approved annually by their county emergency management departments. As a hurricane approaches, they are advised to follow local emergency management guidance. There are no requirements concerning how a decision is made among ALCs concerning whether to evacuate or shelter in place. After the U.S. Gulf Coast hurricanes from 2004–05, the state long-term care trade organization, the Florida Health Care Association, produced a decision-making guide in cooperation with the John A. Hartford Foundation and the University of South Florida.17 This guide focused on nursing homes.

To gain further insight into our findings we additionally examined evacuation status relative to evacuation orders. Overall 196 Florida ALCs sheltered in place though ordered to evacuate (48.0% of all ordered), including 115 with higher care licenses. This evidence that some ALCs sheltered in place though under evacuation orders raises questions related to future disaster planning. While it would seem risky to not follow an evacuation order, did these ALC administrators perceive sheltering in place as the safer option? If so, how was this determined and did residents’ clinical status influence decision-making? Did these ALCs and their local emergency management officials collaborate to assess the risks? Pierce et al. considered the relationship between emergency management agencies and LTC facilities in a recent research review,, suggesting that emergency managers use caution in ordering LTC evacuations.20

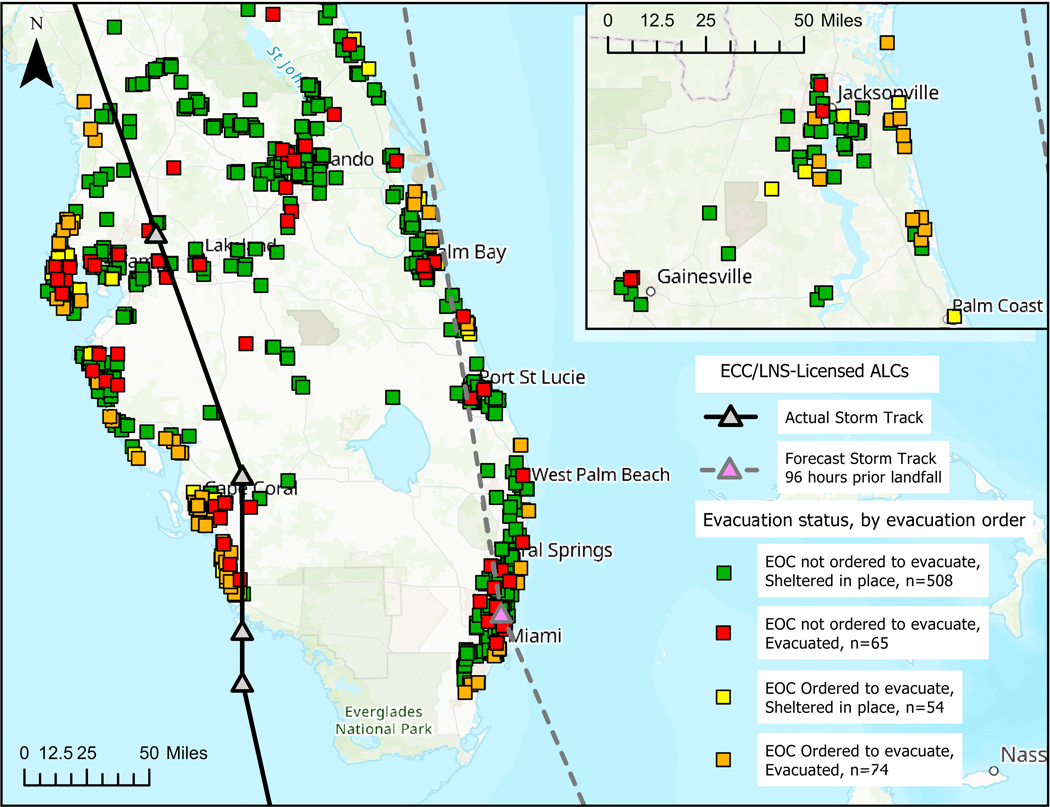

We also observed that 348 ALCs evacuated though not under mandatory orders (13% of all not under orders), including 143 ALCs with higher care licenses. Figure 1 shows the locations and evacuation status, by evacuation order, for ALCs licensed to provide extended and nursing care. Figures A1 and A2 (supplemental) show ALC locations for other license types. We need to know more about why these ALCs evacuated and what assistance, including clinical guidance, might have led them to act otherwise to avoid potentially dangerous resident relocations.

Fig. 1.

Nursing care-licensed ALCs’ evacuation decisions. Partial Florida map of ALCs with extended care and limited nursing licenses that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma. They are differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. Map is limited to the areas most affected by the hurricane – Central and South Florida with an inset of Northeast Florida. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall. (The statewide view is provided in Fig. A3, supplemental.)

Adjusted analyses further showed that ALCs with fewer than 25 beds were more likely than larger ALCs to evacuate. Prior work has found smaller ALCs are less likely to be chain-affiliated.21 They therefore may have less access to training and other resources for safe sheltering in place (e.g. reinforced windows, power generators). Our results are concerning because prior research shows that smaller ALCs are more likely to be home to residents with higher levels of impairment,22 and more impaired residents may be more vulnerable to harm in an evacuation. 6, 7

The lower likelihood of evacuation for ALCs accepting supplemental payments (OSS) may have been related to the large numbers of mental health-licensed ALCs in this payment category, given that in the bivariate analysis, a lower proportion of LMH ALCs evacuated. Results suggest the need to learn more about decision-making for ALCs providing care for residents with mental health diagnoses. Furthermore, results may have been related to the high proportion of ALCs that accept OSS payments in Southeast Florida.

Prior research supports the association of region and evacuation order with evacuation likelihood.5, 23 It is possible the variation among the regions was driven by the public warnings of danger to the Central West coast in the days before the storm’s landfall24 and fears for the regions to the east predicted to be on the storm’s “dirty” side (i.e. the side that can bring stronger winds and tornadoes.25

The present study has limitations. First, it is limited to one state and one storm, though Florida’s older population, large ALC industry, and hurricane vulnerability make these results meaningful to other regions. In addition, we were limited to the self-reported emergency and ALC data collected by the state of Florida. These data lacked information on individual residents and whether ALCs conducted partial evacuations for residents with special needs. The HIFI survey conducted after Hurricane Irma was voluntary and therefore a convenience sample but was collected by a regulatory agency under the state’s authority and used in this research only to supplement the FLHealthStat data. A further limitation is that of the 1,888 ALCs that answered the HIFI survey, 246 (13%) provided different information concerning evacuation status, compared to the information provided to the FLHeathStat reporting system at the time of the hurricane. We believe, however, that using the HIFI data in these cases is justified because this information was provided after the hurricane, when respondents were clear about the actions they took and not under the stress of hurricane preparations.

Conclusions and implications

In conclusion, the uncertainty surrounding hurricanes and the multiple factors influencing LTC residents’ safety make evacuation decisions exceedingly complex. While evacuation can heighten risks for impaired residents, ALCs appear to differ in how they weigh those risks. Our work suggests practitioners in AL and emergency management need to work more closely together concerning ALC disaster planning and response, including balancing being in a vulnerable location and impaired residents’ needs. This may apply especially to smaller ALCs. Further research is under way to learn more about ALC disaster responses and outcomes, including analysis of LTC resident data from Medicare files. This work is expected to generate evidence-based policy recommendations to aid ALCs in planning for future disasters.

Supplementary Material

Fig. A1. Standard-licensed ALCs’ evacuation decision. Florida map of ALCs with only a standard license that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.

Fig. A2. Mental-health care ALCs’ evacuation decisions. Florida map of ALCs with mental health licenses that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.

Fig. A3. Nursing care-licensed ALCs’ evacuation decisions. Florida map of ALCs with extended care and limited nursing licenses that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG060581-01.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT of INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dosa DM, Hyer K, Brown L, et al. Controversies in long-term care: The controversy inherent in managing frail nursing home residents during complex hurricane emergencies. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willoughby M, Kipsaina C, Ferrah N, Blau S, Bugeja L, Ranson D, et al. Mortality in nursing homes following emergency evacuation: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dosa D, Hyer K, Thomas K, et al. To evacuate or shelter in place: implications of universal hurricane evacuation policies on nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:190.e1–190.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Xirasagar S, et al. Providing shelter to nursing home evacuees in disasters: lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1288–1293. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Inspector General. Nursing home emergency preparedness and response during recent hurricanes: OEI-06e06e00020; Washington, DC, August 2006. Report No.: OEI06e06e00020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas KS, Dosa DH, Hyer K, et al. Effect of forced transitions on the most functionally impaired nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1895–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04146.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown LM, Dosa D, Thomas KS, et al. The effects of evacuation on nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2012;27:406–412. doi: 10.1177/1533317512454709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyer K, Polivka-West L, Brown LM. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities: Planning and decision making for sheltering in place or evacuation. Generations 2007;31:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Florida Health Care Association. Caring for vulnerable elders during a disaster: National findings of the 2007 nursing home hurricane summitt. Available at: https://www.ahcancal.org/facility_operations/disaster_planning/Documents/Hurricane_Summit_May2007.pdf; 2007. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 10.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Lendon JP, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016. Vital Health Stat: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. pgs. 1, 22, 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro C, Persson D, Bergstrom N, Cro. Surviving the storms: Emergency preparedness in Texas nursing facilities and assisted living facilities. J Gerontol Nurs 2008;34:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LM, Christensen JJ, Ialynytchev A, et al. Experiences of assisted living faciltiy staff in evacuating and sheltering residents during hurricanes. Curr Psychol 2015;34:506–514. doi: 10.1007/s12144-015-9361-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Minority Staff. Sheltering in danger. November 2018. Available at: https://asprtracie.hhs.gov/technical-resources/resource/6513/sheltering-in-danger. Accessed November 8, 2019.

- 14.Achenbach J, Sullivan P, Berman M. Florida bracing for a direct hit from Irma. Philadelphia Inquirer. Available at: http://www.philly.com/philly/news/nation_world/florida-bracing-for-a-direct-hit-from-irma-20170908.html; 2017. Accessed March 19, 2019.

- 15.Varn K As Hurricane Irma shifts west, Tampa Bay area still at risk. Tampa Bay Times Available at https://www.tampabay.com/news/weather/hurricanes/as-hurricane-irma-shifts-east-tampa-bay-area-still-at-risk/2336633; 2017. Accessed on April 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Street D, Burge S, Quadagno J. The effect of licensure type on the policies, practices, and resident composition of Florida assisted living facilities. Gerontologist 2009;49:211–223. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florida Health Care Association. National criteria for evacuation decision-making in nursing homes. Available at: https://www.in.gov/isdh/files/NationalCriteriaEvacuationDecisionMaking.pdf; 2008. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 18.Florida Division of Emergency Management. Know your zone. Available at: https://www.floridadisaster.org/knowyourzone/. Accessed on April 10, 2019.

- 19.Dosa D, Grossman N, Wetle T, Mor V. To evacuate or not to evacuate: lessons learned from Louisiana nursing home administrators following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(3):142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce JR, Morley SK, West TA. Improving long-term care facility disaster preparedness and response: A literature review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2016;11:140–149. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caffrey C, Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M. Variation in Operating Characteristics of Residential Care Communities, by Size of Community: United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics data brief, no. 222. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db222.htm. Accessed April 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta M, Harris-Kojetin L, Caffrey C. Variation in Residential Care Community Resident Characteristics, by Size of Community: United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics data brief, no. 23. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db223.htm. Accessed April 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhoads J, Clayman A. Learning from Katrina: Preparing long-term care facilities for disasters. Geriatr Nurs 2008;29:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNeill CM, McGrory K. With Hurricane Irma on track for Tampa Bay, here’s what you can expect. Tampa Bay Times. Available at https://www.tampabay.com/news/weather/hurricanes/with-hurricane-irma-on-track-fortampa-bay-heres-what-you-can-expect/2336896; 2017. Accessed on May 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cappucci M Dissecting the parts of a hurricane. The Washington Post. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2017/09/10/dissecting-the-parts-of-a-hurricane/?utm_term=.95702fb20cd2; 2017. Accessed on May 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. A1. Standard-licensed ALCs’ evacuation decision. Florida map of ALCs with only a standard license that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.

Fig. A2. Mental-health care ALCs’ evacuation decisions. Florida map of ALCs with mental health licenses that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.

Fig. A3. Nursing care-licensed ALCs’ evacuation decisions. Florida map of ALCs with extended care and limited nursing licenses that evacuated (red and orange) or sheltered in place (green and yellow) for Hurricane Irma; differentiated by whether they were under an evacuation order. The solid black line shows the actual path of Hurricane Irma; the dotted gray line was the projected path 96 hours before landfall.