Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of changes in assisted living (AL) capacity within a market on prevalence of residents with low care needs in nursing homes.

Design

Retrospective, longitudinal analysis of nursing home markets.

Setting and participants

Twelve thousand two hundred fifity-one nursing homes in operation during 2007 and 2014.

Measurements

We analyzed the percentage of residents in a nursing home who qualified as low-care. For each nursing home, we constructed a market consisting of AL communities, Medicare beneficiaries, and competing nursing homes within a 15-mile radius. We estimated the effect of change in AL beds on prevalence of low-care residents using multivariate linear models with year and nursing home fixed effects.

Results

The supply of AL beds increased by an average 258 beds per nursing home market (standard deviation = 591) during the study period. The prevalence of low-care residents decreased from an average of 13.0% (median 10.5%) to 12.2% (median 9.5%). In adjusted models, a 100-bed increase in AL supply was associated with a decrease in low-care residents of 0.041 percentage points (P = .026), controlling for changes in market and nursing home characteristics, county demographics, and year and nursing home fixed effects. In markets with a high percentage of its Medicare beneficiaries (≥14%) dual eligible for Medicaid, the effect of AL is stronger, with a 0.066–percentage point decrease per 100 AL beds (P = .026) vs a 0.016–percentage point decrease in low-duals markets (P = .48).

Conclusions and implications

Our analysis suggests that some of the growth in AL capacity serves as a substitute for nursing homes for patients with low care needs. Furthermore, the effects are concentrated in markets with an above-average proportion of beneficiaries with dual Medicaid eligibility.

Keywords: Assisted living, long-term care, nursing home residents

Assisted living (AL), also known as residential care, communities have been defined as “congregate residential settings that provide or coordinate personal services, 24-hour supervision and assistance (scheduled and unscheduled), activities, and health-related services.”1

Distinct from nursing homes, AL communities typically do not provide skilled nursing care and instead prioritize residents’ independence, dignity, and choice, and provide privacy and a homelike environment.2 AL communities comprise a growing segment of the long-term care industry, and in 2014, there were 30,200 AL providers serving 835,200 residents.3

Because of nursing homes’ emphasis on providing 24-hour skilled care, residents of nursing homes who have “low care needs” may be better served in less restrictive settings, such as AL. Previous studies have found that the prevalence of low-care residents in nursing homes has decreased over time and is related to market dynamics, including funding for non-institutional alternatives to nursing homes such as Medicaid HCBS4,5 and Title III programs including home-delivered meals6 and personal care services.7 However, although the prevalence of low-care patients in nursing homes has decreased over the last decade, it remains unclear how much of the decrease is explained by the growth of the AL industry.

For older and disabled individuals, AL can serve as a substitute for nursing home care. Previous studies suggest that growth in the supply of AL is associated with changes in nursing homes residents’ characteristics (eg, case-mix acuity and cognitive performance),8 payer mix,9 financial performance,10 and quality measures.11 These studies highlight the potential interchangeability of AL for nursing home care. But, we are not aware of any published studies that quantify the substitution between AL and nursing home care, specifically for low-care residents, using national data.

To address the gap in the literature, we examine the effect of a change in AL capacity in a nursing home market on the prevalence of low-care nursing home residents, using data from 46 states in 2007 and 2014. As the local supply of AL increases, the residents who occupy new units are presumably a mix of households that would stay home with paid support or move to a nursing home in the absence of AL in the market. Thus, the working hypothesis of this study is that as the supply of AL beds in a market increases, the prevalence of low-care residents in nursing homes will decrease as some individuals choose the less-restrictive AL option in favor of institutional custodial care.

Dramatic decreases in low-care prevalence and increases in AL capacity took place prior to the time period of the study. Therefore, we wanted to explore later market entrants that may have been motivated by the increased availability of Medicaid funding for AL through waiver services.12 As a secondary research question, we explore whether the recent effects are concentrated in markets with above-average proportion of dual-eligible Medicaid beneficiaries.

Study Data and Methods

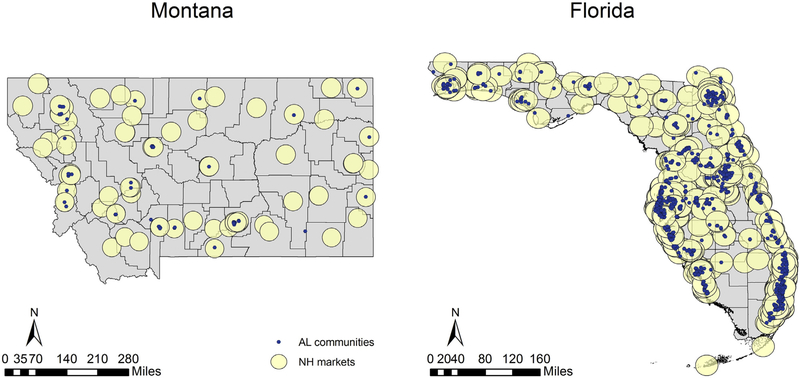

Data on AL communities came from a national census of licensed AL communities that was compiled by the authors from individual state licensing agencies in 2007 and again in 2014. Following the work of others, we defined “assisted living” as a community with 25+ beds and licensed to serve an older population.8,13,14 Alaska, Hawaii, and the District of Columbia were excluded as not part of the contiguous 48 states. We also removed Indiana and Tennessee because dramatic changes in the number of AL communities suggested that we were missing data for 1 or more license types in either year. Data on nursing homes came from LTCFocus.org. The final sample included 12,251 nursing homes open in both years. We constructed a measure of AL supply within a nursing home’s market as the number of AL beds within a 15-mile radius of each nursing home (see Figure 1). The exposure variable is operationalized as the total number of AL beds (in hundreds) within a 15-mile radius of a nursing home (more detail about the sample selection and creation of nursing home markets can be found in the online supplementary material). In a sensitivity analysis, we aggregated the data to the county level, following previous literature (see online supplementary material).8

Fig. 1.

Map of nursing home markets and assisted living supply in Montana and Florida in 2014. (Basemap sources EsriTraningSvc. 2019; Montana State Library 2019).

Our outcome variable is the percentage of low-care residents in a nursing home. Nursing home residents were identified as low care if they required no physical assistance in any of the 4 late-loss activities of daily living (bed mobility, toileting, transferring, and eating) and were not classified in either the “special rehab” or “clinically complex” resource utilization groups (RUG-III). Data were aggregated to the facility level to derive percentage of low-care residents in the nursing home on the first Thursday of April in 2007 and 2014. Covariates are listed in Table 1. We included nursing home level, and market level, and county characteristics based on their relationship with the prevalence of low-care residents.

Table 1.

Nursing Home and Market Characteristics in 2007 and 2014

| 2007 | 2014 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assisted living communities in market | |||

| AL communities in market | 22.9 (28.0) | 25.5 (30.9) | <.001 |

| AL beds in market (100s) | 21.1 (31.4) | 23.6 (33.7) | <.001 |

| NH characteristics | |||

| Percentage residents who are low care | 13.0 (11.5) | 12.2 (11.6) | <.001 |

| Total beds | 112.3 (61.7) | 111.5 (60.4) | .30 |

| Occupancy rate | 85.1 (14.4) | 82.7 (14.1) | <.001 |

| Part of a chain, % | 54.6 | 56.3 | .009 |

| Run for profit, % | 72.3 | 75.0 | <.001 |

| Market characteristics | |||

| Other NHs in market | 33.4 (46.5) | 32.5 (44.7) | .14 |

| Other NH Alzheimer’s special care units | 5.0 (7.2) | 4.1 (5.7) | <.001 |

| Medicare beneficiaries over age 85 in market (1000s) | 15.1 (26.0) | 17.7 (29.7) | <.001 |

| Medicare/Medicaid dual beneficiaries (1000s) | 19.2 (45.7) | 24.2 (58.4) | <.001 |

| County characteristics | |||

| Percentage persons in poverty | 13.2 (5.1) | 15.6 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Unemployment rate | 4.8 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.7) | <.001 |

| Percentage black | 59.2 (150.7) | 84.8 (225.3) | <.001 |

| Percentage Hispanic/Latino | 10.6 (12.4) | 11.2 (12.6) | <.001 |

| Percentage other nonwhite | 9.8 (13.3) | 12.8 (14.6) | <.001 |

NH, nursing home.

Markets are defined as the geographic area within a 15-mile radius of a nursing home. Unless otherwise noted, values are mean (SD). Sample includes 12,251 NHs open in both years. Alaska, Hawaii, District of Columbia, Indiana, and Tennessee are excluded.

Empirical Specification

Our analysis estimates the effect of AL capacity in a nursing home’s market on the prevalence of low-care residents in that nursing home. We used nursing home and year fixed effects to control for time-invariant, market-specific differences, and for national trends in nursing home utilization. We estimated models using the xtreg command in Stata, version 15.5 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

To test the hypothesis that the effect of AL market entry is stronger in markets with higher proportion of duals in its population, we calculated the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries in the market with ≥1 month of dual eligibility, and stratified the sample into low-duals (≤14%) and high-duals (>14%) markets based on the market median.

Model Checks

As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the analyses with the county as the unit of analysis. As a falsification test, we estimated models with alternative outcomes reflecting measures of high care need: the percentage of residents treated with a ventilator, and the percentage admitted from an acute care hospital. A large or statistically significant effect of AL growth on these high-need measures would suggest a confounding factor influencing both nursing home case-mix and AL capacity.

This project was determined exempt from human-subjects review by the Brown University institutional review board. The work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (Grant R21 AG047303) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (CDA 14–422).

Results

Unadjusted Results

The number of AL communities with 25+ beds in our sample of states increased from 10,644 in 2007 to 11,893 in 2014. The average supply of AL beds in the markets of the 12,845 nursing homes in our study increased by an average 258 beds (standard deviation = 591), a 12% increase from 2007 to 2014. There was variability among markets in the AL rate of change, with a 259-bed decrease at the 5th percentile and 1315-bed increase at the 95th percentiles. Mean and standard deviation of the outcome and explanatory variables in the models are reported in Table 1. The prevalence of low-care residents decreased from an average of 13.0% (median 10.5%) to 12.2% (median 9.5%).

Main Regression Results

Table 2 reports estimates for the effect of an additional 100 AL beds in a nursing home market on the percentage of low-care residents in that nursing home. In model 2, our preferred specification including covariates, an increase of 100 AL beds is associated with a decrease in prevalence of low-care residents of 0.041 percentage points (P = .026). To put the magnitude of this result in context, for a typical 125-bed nursing home that provides 6000 days of care, per year, to low-care residents, the opening of a nearby 100-unit AL community would result in 2.4 fewer low-care resident days per year in that nursing home.

Table 2.

Results of a Multivariate Model to Examine the Effect of Assisted Living Supply on the Percentage of Nursing Home Residents Who Are Low Care, Including Time and Facility Fixed Effects

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | High-Duals Market | Low-Duals Market | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assisted living beds in market (100s) | −0.017 (0.015) | −0.041* (0.018) | −0.066* (0.030) | −0.016 (0.023) |

| Total beds in NH | −0.799** (0.099) | 0.007 (0.189) | −1.332** (0.285) | 0.703** (0.261) |

| NH occupancy rate | 0.020** (0.006) | 0.012 (0.008) | 0.026** (0.007) | |

| Part of a chain | 0.022** (0.007) | 0.020 (0.011) | 0.023* (0.010) | |

| Run for profit | 0.255 (0.204) | 0.211 (0.302) | 0.166 (0.261) | |

| Other NHs in market | −0.729* (0.360) | −0.688 (0.553) | −0.902* (0.448) | |

| Other NH Alzheimer’s special care units in market | −0.035 (0.041) | −0.170** (0.060) | −0.057 (0.062) | |

| Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥85 y in market (1000s) | −0.076 (0.040) | −0.022 (0.077) | −0.076 (0.046) | |

| Medicare/Medicaid dual beneficiaries in market (1000s) | 0.017 (0.051) | −0.111 (0.067) | 0.136 (0.090) | |

| County % persons in poverty | −0.006 (0.013) | 0.02 (0.016) | −0.096* (0.042) | |

| County unemployment rate | 0.242** (0.051) | 0.189** (0.068) | 0.227** (0.073) | |

| County no. of home health agencies | −0.515** (0.089) | −0.338** (0.127) | −0.194 (0.125) | |

| County % black | −0.006** (0.002) | −0.005* (0.002) | 0.001 (0.004) | |

| County % Hispanic/Latino | 0.128* (0.054) | 0.053 (0.081) | 0.026 (0.070) | |

| County % other nonwhite | −0.184** (0.044) | −0.067 (0.058) | −0.286** (0.070) | |

| Year = 2014 | 0.007 (0.065) | −0.058 (0.077) | 0.088 (0.130) | |

| Constant | 13.367** (0.320) | 11.537** (1.997) | 22.256** (3.589) | 7.962** (2.288) |

| R-squared | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.047 |

| Number of nursing homes | 12,251 | 12,251 | 6189 | 6062 |

NH, nursing home.

High-duals markets are defined as >14% of Medicare beneficiaries dual-eligible at least 1 month of the year. Markets are defined as the geographic area within a 15-mile radius of a nursing home. Alaska, Hawaii, District of Columbia, Indiana, and Tennessee are excluded. All models include year and nursing home fixed effects. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by ZIP code.

P < .05

P < .01.

In a falsification check (see Supplementary Table 3), the effects of AL growth in residents being treated with a ventilator, or residents admitted from an acute care hospital stay, were small in magnitude and not statistically significant.

High-Duals Markets

The increase in AL beds was greater in markets with a low percentage of duals (≤14%) than in high-duals markets, with an average increase of 287 beds in low-duals markets vs 228 beds in high-duals markets (paired t test, P < .001; see Supplementary Table 1). The effect of AL supply on nursing home low-care prevalence was stronger in markets with a higher proportion of duals: in high-duals markets, 100 additional AL units were associated with a 0.066-percentage point decrease in low-care prevalence per nursing home (P = .026), whereas in low-duals markets we estimated a non-statistically significant effect of −0.016 percentage points (P = .48). For a 125-bed nursing home in a high-duals market that provides 6700 low-care days per year, 100 new AL units in the market would lead to approximately 4.4 fewer low-care resident days provided in that nursing home. A similarly sized nursing home in a low-duals market with the average 5600 low-care resident days would see a typical decrease of only about 0.8 low-care resident days.

It is important to note that because of the overlap among nursing home markets (see Figure 1), introduction or expansion of a single AL community affects multiple nursing homes within 15 miles. Thus, the aggregated change in the number of low-care patients of nursing homes that occurs as a result of change in AL supply varies with the concentration of nursing homes. For new AL with few nursing homes nearby (0–5), 100 new AL units result in a decrease of about 0.2 low-care patients in surrounding nursing homes, or about 70 fewer days ofcare to low-care patients. Among AL units with a high concentration of nursing homes (40 to ≥200), the resulting change is about 2 to 4 fewer low-care patients in the nearby nursing homes, or about 1000 fewer days provided to low-care patients (see Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we found that increase in the supply of AL beds in a nursing home market leads to a small but statistically significant decrease in the percentage of low-care residents in that nursing home. The effect is stronger in markets where the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who were dually eligible for Medicare was higher than average. This finding is consistent with other studies that suggest that while most of the increase in the AL population is drawn from households that would otherwise use informal or formal home care services, a small margin includes some people who substitute AL for nursing home care.5,8,9 We also found that the effect of AL supply is stronger in markets with a higher percentage of duals in the community.

Both demand- and supply-related mechanisms may explain the observed relationship between AL growth and decreased low-care prevalence in nursing homes. On the consumer side, older adults with resources to pay out of pocket, and whose needs are minimal, may favor the independence, privacy, and homelike environments that AL communities are able to provide. Thus, AL operators respond to demand in markets where consumer preferences and resources favor those attributes. For older adults whose poverty qualifies them for Medicaid, an expanding number of state waiver programs cover personal care in AL through waiver programs or state plans, up from 39 states in 2007 (Table 3 in Mollica15) to 48 states in 2014.12,15 The secondary finding in this article, that the substitution effect of AL for nursing home care is stronger in markets with a high proportion of duals among its Medicare beneficiaries, suggests that the opportunity is greater in these markets to divert frail and disabled Medicaid older adults from nursing homes to AL care. Low-care residents in nursing homes are disproportionately funded by Medicaid for their nursing home care.6 Furthermore, although impoverished residents have fewer opportunities for AL, which are largely paid for by private funds, state Medicaid programs have expanded the generosity and scope of home- and community-based services waivers and personal care state plans,16 which often cover services provided in AL. Although Medicaid-funded residents still comprise a relatively small proportion of the total AL market (16% in 2016, Figure 23 in Harris-Kojetin),17 the expansion of these subsidies may have released pent-up demand for AL in the Medicaid population who could not previously afford private residential care in these settings.

On the supply side, as nursing homes seek to fill beds with post-acute patients whose more complex medical needs demand higher Medicare per-diem charges,18 they may be reducing the number of beds available for low-care residents whose care needs are not adequately captured by the Resource Utilization Grouping that forms the basis for Medicare reimbursement, and the majority of whom are paid for by Medicaid. Thus, AL expansion in some markets may be a response to meet the needs of these low-care individuals that are not met by nursing homes.

This study makes several key contributions to understanding the relationship between the markets for AL and nursing home care. First, the longitudinal study design allows us to control for nursing home and geographic characteristics through the use of facility fixed effects and secular trends through a time fixed effect. Second, by using geocodes we were able to define nursing home markets that better reflect the potential resident population than markets based on county or state boundaries.

Several limitations of this study are important to note. First, our data set is limited to assisted living communities with 25 or more beds, and may fail to capture the effect of an increasing number of heterogeneous smaller AL communities. The design of this study controls for cross-sectional and time-varying confounders but does not indicate the direction of causality; that is, whether the association is driven by nursing homes, AL, or unobserved, time-varying market factors that affect both, such as consumer preferences.

Conclusions and Implications

The goals of AL care are to accommodate residents’ needs for care while preserving their dignity, autonomy, and privacy in a homelike environment. The growth of AL supply suggests that these communities are fulfilling an important need on the care continuum, including the needs of some individuals who may not require 24-hour skilled care provided in nursing homes. However, the magnitude of our finding is small, suggesting that decreases in low-care residents in nursing homes may be driven by many factors other than increases in AL supply. For example, higher per diem rates for post-acute care are an incentive to switch custodial-care beds to beds for residents requiring skilled, post-acute care. This trend is reflected in an increase in the percentage of residents admitted from an acute care hospital (an increase in the average from 72% of new admissions in 2007 to 81% in 2014). The total nursing home population has also decreased; in the nursing homes in our sample, the average occupancy decreased from 95 to 91 patients from 2007 to 2014. And although our sample included only facilities open in both time periods, the total number of nursing homes in operation also decreased. Consumers may be exercising their preference for noninstitutional care by remaining longer in their own homes, using a combination of privately and publicly funded home health and home personal care services. The prevailing trend of decreasing low-care residents in nursing homes may suggest that older adults who need long-term care may prefer not to live in a nursing home. But given that the vast majority of AL beds are privately financed,17 that trend signals a divergence of access between the wealthy who can afford AL through long-term care insurance or out-of-pocket savings and the poor—especially in states with no Medicaid coverage for AL. AL communities also are subject to far less regulation and oversight than nursing homes. On the one hand, less oversight may give AL operators the flexibility to create communities that conform to residents’ preferences and reduce the costs associated with compliance; on the other, little is known about how regulatory environments affect the safety of care in AL. As we witness an aging population and increases in long-term care substitutes to nursing homes provided by AL, these questions about access, oversight, and patient outcomes are important areas for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R21 AG047303 to KST), the National Institute on Aging (1 R21 AG059120 01 to KST), and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (CDA 14-422 to KST).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Insitutes of Health, or the United States government.

References

- 1.Assisted Living Coalition. Assisted Living Quality Initiative: Building a Structure That Promotes Quality. Washington, DC: Assisted Living Coalition; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawes C, Phillips CD, Rose M, et al. A national survey of assisted living facilities. Gerontologist 2003;43:875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 2016;38:x–xii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, et al. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1762–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn EA, Thomas KS, Hyer K, et al. Predictors of low-care prevalence in Florida nursing homes: The role ofMedicaid waiver programs. Gerontologist 2011;51: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas KS, Mor V. The relationship between Older Americans Act Title III state expenditures and prevalence of low-care nursing home residents. Health Serv Res 2013;48:1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas KS. The relationship between Older Americans Act in-home services and low-care residents in nursing homes. J Aging Health 2014;26: 250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG, Cornell PY. Assisted living expansion and the market for nursing home care. Health Serv Res 2012;47:2296–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver BC, Grabowski DC, Gozalo PL, et al. Increasing prevalence of assisted living as a substitute for private-pay long-term nursing care. Health Serv Res 2018;53:4906–4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord J, Davlyatov G, Thomas KS, et al. The role of assisted living capacity on nursing home financial performance. Inquiry 2018;55:46958018793285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowblis JR. Market structure, competition from assisted living facilities, and quality in the nursing home industry. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 2012;34: 238–257. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Government Accountability Office. Medicaid Assisted Living Services: Improved Federal Oversight of Beneficiary Health and Welfare is Needed. (Publication No. GAO-180–179). Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-179; 2018. Accessed February 6, 2020.

- 13.Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Sizing up the market for assisted living. Health Aff 2010;29:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Gozalo PL, et al. A methodology to identify a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries residing in large assisted living facilities using administrative data. Med Care 2018;56:e10–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mollica RL. State Medicaid Reimbursement Policies and Practices in Assisted Living. National Center for Assisted Living American Health Care Association; Available at: https://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/advocacy/Documents/MedicaidAssistedLivingReport.pdf; 2019. Accessed February 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, Amos A. Medicaid expenditures for long-term services and supports in FY 2016. IBM Watson Health; Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/downloads/reports-and-evaluations/ltssexpenditures2016.pdf ; 2018. Accessed February 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Lendon JP, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3; 2019;43:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyler DA, Feng Z, Leland NE, et al. Trends in postacute care and staffing in US nursing homes, 2001–2010. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:817–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.