Abstract

Low-wage migrant workers in Singapore are legally entitled to healthcare provided by their employers and supported by private insurance, separate from the national UHC (universal health coverage) system. In practice, they face multiple barriers to access. In this article, we describe this policy-practice gap from the perspective of HealthServe, a non-profit organisation that assists low-wage migrant workers. We outline the healthcare financing system for migrant workers, describe commonly encountered barriers, and comment on their implications for the global UHC movement’s key ethical concepts of fairness, equity, and solidarity.

Keywords: Universal health coverage, UHC, Healthcare access, Health financing, Migrant health, Migrant workers, Health equity

Introduction: Migrant Workers in Singapore

Singapore is a favoured destination for international labour migrants, with high satisfaction regarding pay, living conditions, safety, and security (Ministry of Manpower 2019a). Migrant workers are a significant part of the landscape, comprising 24.3% of Singapore’s population and 37% of its workforce (Ministry of Manpower 2019b, 2019c). They are separated into visa categories linked to skill level and earnings, with each category governed by distinct immigration and social policies.

Male ‘Work Permit’ holders are the largest category, numbering 716,200 or 12.7% of Singapore’s population (Ministry of Manpower 2019b). They are a well-defined group, originating from a small set of approved source countries (mainly Bangladesh, India, and China) and performing low-skilled work in selected sectors (construction, manufacturing, marine, shipyard, process, or service) (Ministry of Manpower 2019d, 2019e). In this article, we restrict the discussion to male Work Permit holders, and we use the term ‘Migrant Worker’ to refer to this group throughout.

HealthServe is a non-profit organisation that assists migrant workers’ health and other welfare needs in Singapore. In the course of operations, we frequently encounter migrant workers facing intractable barriers to accessing their legal healthcare entitlements. In this paper, we offer HealthServe’s perspective and reflections on these experiences.

Healthcare Financing System, for Singaporeans and Migrant Workers

Singapore’s healthcare system is highly successful, consistently top-ranked for efficiency (Bloomberg 2014), outcomes (Economist Intelligence Unit 2014), and overall performance (WHO 2000).

Healthcare financing policy differentiates between Singaporean nationals (‘Singaporeans,’ citizens, and permanent residents) and non-nationals, essentially providing universal health coverage (UHC) to Singaporeans but offering separate, primarily private insurance-based mechanisms for non-nationals (including migrant workers).

Healthcare financing for Singaporeans is built upon four pillars: Subsidised healthcare and the ‘3 Ms’ (Table 1). Subsidised care is provided by government facilities, in some instances scaled in accordance with class tiers and means testing. Medisave is a compulsory individual medical savings scheme, which can be used to pay for selected medical expenses as well as medical insurance premiums. Medishield Life is a low-cost nationalised medical insurance scheme, with cross-subsidies for some constituencies. Medifund is a safety net medical endowment fund for essential medical expenses for the indigent.

Table 1.

Key elements of healthcare financing for Singapore residents

| Subsidised healthcare | |

| Medisave (compulsory individual medical savings) | |

| Medishield Life (low-cost nationalised medical insurance) | |

| Medifund (safety net medical assistance fund) |

Migrant workers do not receive subsidised care and are not covered by the 3 Ms. Healthcare financing for them is instead built upon the principle of ‘employer responsibility’ and supported by mandatory private medical insurance and private work injury compensation insurance (Employment of Foreign Manpower Act 2009). Specific parameters, such as minimum mandated coverage for healthcare insurance, are subject to regular review (Ministry of Manpower 2012).

In principle, ‘employer responsibility’ implies assurance of access to essential health services, the sine qua non of UHC (Ministry of Manpower 2010):

Under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act, employers are responsible for and must bear the costs of the upkeep and maintenance of their work permit holders … This includes the provision of any medical treatment that the worker requires … employers bear the full costs of bringing in foreign workers, rather than impose them on society.

The resulting system for healthcare financing for migrant workers is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key elements of healthcare financing for male work permit holders in Singapore

| Not eligible for subsidised healthcare. Prices set by market. | |

| Not eligible for Medisave, Medishield, or Medifund. | |

|

Employment of Foreign Manpower Act (Ministry of Manpower 2015): Employers’ responsibility for costs of work permit holders’ medical treatment (both work-related and non-work-related). | |

|

Mandatory medical insurance SGD 15,000 (Ministry of Manpower 2019f): Covers: inpatient care, day surgery Does not cover: outpatient care (primary care or specialist care) Co-payment by male work permit holders is limited to 10% of worker’s monthly salary, for 6 months | |

| Mandatory workplace injury compensation insurance SGD 36,000 (Ministry of Manpower 2018) |

Barriers to Healthcare Access for Migrant Workers, from the Perspective of HealthServe

Universal health coverage (UHC) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as providing all people with access to needed health services without incurring financial hardship (WHO 2014a). It is a major current trend in global health policy and central to the health goals for the post-2015 development agenda (WHO 2014b).

Singapore’s health system is considered to have achieved UHC for residents (Haseltine 2013; Global-is-Asian 2018) and scores well in reported universal indices of UHC (WHO 2019).

The healthcare access of migrant workers in Singapore is less well described, with no official statistics reported, and only a handful of mostly qualitative and small-sample quantitative studies published (Lee et al. 2014; Tam et al. 2017; Ang et al. 2017; Ang et al. 2019).

There are indications that the regime is successful in enabling access to care in the majority of cases, e.g. Lee et al. (2014) found 87% of male work permit workers who reported having had an illness episode saw a doctor in Singapore. However, a sizeable minority of migrant workers nevertheless face barriers to accessing healthcare (Lee et al. 2014; Guinto et al. 2015; Ang et al. 2017; Chan and Chia 2017; Kaur et al. 2017; Tam et al. 2017; Fillinger et al. 2017; Ang et al. 2019).

HealthServe (Table 3) frequently encounters migrant workers who face intractable barriers to accessing their legal healthcare entitlements.

Table 3.

HealthServe (http://www.healthserve.org.sg/about/)

| Founded in 2006 | |

| Non-profit organisation focused on migrant workers in Singapore | |

| Vision: A society where every migrant worker lives a life of dignity | |

|

Mission: - To serve disadvantaged migrant workers in Singapore through healthcare, counselling, casework, and social assistance. - To advocate for and raise awareness of the needs of migrant workers. - To bridge communities through meaningful partnerships and being a platform for effective volunteerism | |

|

Areas of work: - Healthcare - Mental health - Casework and counselling - Social assistance - Events and outreach - Education, research, and advocacy | |

|

Health-related work: - Low-cost, volunteer-run clinics providing primary care (medical and dental), limited specialist care, and ancillary services - Referral partnerships and care coordination - Health screening - Health promotion |

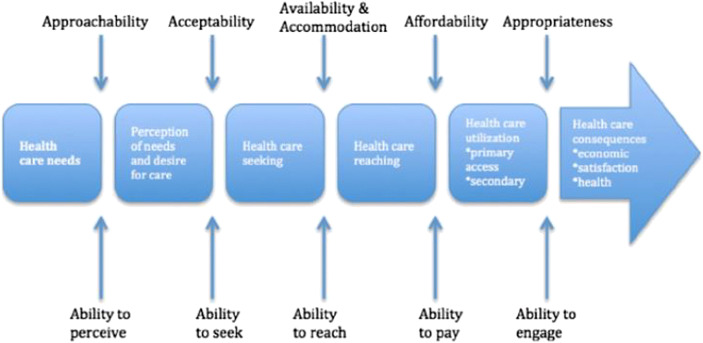

Levesque et al.’s (2013) framework (Fig. 1) conceptualises access to healthcare in 6 broad dimensions and their corresponding supply-side and demand-side factors. This framework is commonly invoked in analyses of migrant health access (Chuah et al. 2018; WHO Office for Europe 2018) and provides a robust systems perspective.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual framework of access to healthcare (Levesque et al. 2013, 05)

In the following text, we describe HealthServe’s observations of healthcare access barriers faced by migrant workers in Singapore, using the constructs in Levesque’s framework, which capture the user’s experience of healthcare: the abilities to perceive healthcare needs, seek, reach, and pay for healthcare, and engage with the healthcare system. This is followed by our reading of the salient underlying contextual factors, before commenting on implications for the global UHC movement’s key ethical concepts.

Ability to Perceive

Migrant workers are assiduous in seeking healthcare for acute complaints that are perceived as potential threats to their earning capacity (Tam et al. 2017), 84% of Ang et al.’s (2017) respondents having seen a doctor in Singapore apart from statutory medical examination. There is lower perceived need for chronic disease care, and as a result, HealthServe’s clinics routinely encounter complications such as those arising from poorly controlled diabetes and hypertension.

Ability to Seek

We frequently observe reluctance to seek care, occuring across the full spectrum of healthcare needs and severities: non-work related minor acute illnesses (e.g. coughs and colds), major acute illnesses (e.g. acute abdominal syndromes), chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, hypertension), work injuries (e.g. fractures, burns), and occupational diseases (e.g. irritant contact dermatitis).

As alternatives to conventional medical care provided by employers, migrant workers resort to self-treatment, remote treatment (e.g. friends transporting medications from home countries), traditional medicine, non-profit organisations, paying out of pocket for care at private primary care providers (Guinto et al. 2015), awaiting return to home countries for care, or simply foregoing care (Lee et al. 2014; Tam et al. 2017). In some cases, pursuit of these alternatives compromises the quality or timeliness of essential care, with adverse health consequences: we see patients with complications of uncontrolled diabetes, poorly healed fractures, and advanced cancers. We elaborate on underlying contextual factors for this reluctance to seek care below.

Ability to Reach

The availability to reach some categories of care is limited, a prime example of which is mental health. The prevalence of some form of psychological distress is estimated to be 15–20% of migrant workers (Ang et al. 2017). In our experience, the dominant syndromes are adjustment and mood disorders, with the most important stressors being family-related (e.g. expectations of meeting financial needs), work-related (e.g. treatment by employers), and financial (mainly debts related to recruitment costs). Mental health services at scale for migrant workers were non-existent prior to HealthServe’s 2019 launch of a comprehensive programme covering prevention, screening, and multi-modality treatment.

Ability to Pay

Although employers are required to provide all essential medical care and mandatory medical insurance covers inpatient care and day surgery, HealthServe and other non-profits routinely encounter migrant workers who pay out of pocket because of lack of understanding of their entitlements (Ang et al. 2017), reluctance to approach their employers, or denial by employers of such claims (Fillinger et al. 2017, 84, 93).

Ability to Engage

Migrant workers in Singapore generally come from backgrounds of low socio-economic status and educational attainment. Navigating Singapore’s healthcare system can be especially challenging due to language and cultural differences with healthcare providers (Ang et al. 2017). HealthServe frequently hears experiences of migrant workers who have been through an episode of acute care in a hospital, and emerge with little understanding of the diagnosis, treatment provided, and follow-up plans.

Underlying Contextual Factors

Our reading of the main underlying contextual factors for migrant workers’ barriers to accessing healthcare is the combination of high costs, employer gatekeeping of healthcare, and vulnerability to repatriation.

High Costs of Healthcare

The cost of healthcare in Singapore is high for migrant workers relative to their incomes. For example, according to the latest available data, the median fee for a primary care consultation at a private general practitioner is SGD 39.64 (Tay et al. 2017), and the median total bill of a simple appendectomy at a public hospital is SGD 6356 (Ministry of Health 2020). The average monthly basic salary for migrant workers in 2016 was SGD 726 (Au 2016, 26).

The cost of healthcare in Singapore is also significantly higher for migrant workers than for Singaporeans. Subsidies for healthcare at public facilities for migrant workers were withdrawn in 2008. Part of the policy rationale was redirection of subsidies to needy Singaporeans: ‘It is not an insignificant sum – S$36mil per year. We will plough it back to subsidise the growing number of elderly Singaporeans.’ (The Star 2006).

No data is reported on the adequacy of mandatory medical and work injury insurance limits to meet the distribution of incurred expenses. In HealthServe’s experience, it does appear that these limits are easily breached (Guinto et al. 2015); hence, public institutions bear a significant burden of bad debt from unpaid bills and experience pressure to limit care. For example, the Workplace Injury Compensation Act (WICA) stipulates employers are required to carry insurance and are liable for medical expenses of up to a maximum of SGD 36,000 or up to 1 year from date of a workplace accident, whichever comes first (Ministry of Manpower 2018). Industrial accidents involving head injuries or polytrauma typically require multiple surgeries followed by high dependency unit stays, easily accruing bill sizes of SGD 100,000 to 200,000.

Employer Gatekeeping of Healthcare

Employers both bear these high costs of their employees’ care and act as gatekeepers for access. The law obligates employers to provide ‘any medical treatment that the worker requires’ (Ministry of Manpower 2010). Common practice in non-emergency contexts is for healthcare providers to involve employers in decision-making before administration of treatment in Singapore, and in some instances, the option of travel to home country to receive treatment. This de facto leaves to the discretion of the employer the provision of any non-emergency medical treatment, including minor acute illness care and chronic disease care.

One mechanism through which employers exercise gatekeeping of migrant workers’ care is the ‘Letter of Guarantee’ (LoG), which guarantees health service providers that employers will pay costs incurred. Numerous non-emergency services such as hospital admission, specialist outpatient clinic consultation, and imaging require migrant workers to produce a LoG, without which they are required to pay an out-of-pocket deposit, normally far exceeding financial means (Chan and Chia 2017). LoG is often required for services, which would be covered by mandatory medical insurance, such as inpatient care and day surgery.

Employers face significant additional disincentives to providing care for work-related injuries, in order to escape the Workplace Safety and Health regime’s penalties and Workplace Injury Compensation Act (WICA) pay-outs. These comprise a significant proportion of HealthServe’s casework and legal assistance cases.

One troubling aspect of this dynamic was the potential for collusion between employers and private healthcare providers to circumvent reporting requirements by calibrating the duration of medical leave from work (Lee 2012; Rajaraman 2017). This risk may be ameliorated by impending amendments to reporting criteria (Ministry of Manpower 2019g).

Vulnerability to Repatriation

Complicating the high costs of healthcare and employers’ gatekeeping of access to healthcare is migrant workers’ vulnerability to repatriation (Harrigan and Koh 2015; Harrigan et al. 2017; Kaur et al. 2017).

Migrant workers typically begin their contracts in Singapore in debt, having incurred substantial up-front recruitment costs typically equivalent to 1 year’s gross earnings. Fillinger et al. (2017), for example, report that Bangladeshi workers pay between SGD 5000 and 15,000 in recruitment costs for roles earning SGD 400 to 800 a month. When this outlay is financed by debt, it becomes especially important for migrant workers to preserve their jobs (Harrigan et al. 2017; Platt et al. 2017).

Fear of termination and repatriation is expressed often, as the work permit system predicates workers’ continued residence in Singapore upon continued employment with their sponsoring employers, with limited mobility between employers. Ten percent of male work permit holders report having been directly threatened with being ‘sent home’ by employers (Harrigan et al. 2017).

This combination of contextual factors (high costs of healthcare, employer gatekeeping of healthcare, and vulnerability to repatriation) creates a dynamic where migrant workers face disincentives and barriers to seeking, reaching, and paying for healthcare.

Migrant Workers in Singapore and the Global UHC Movement

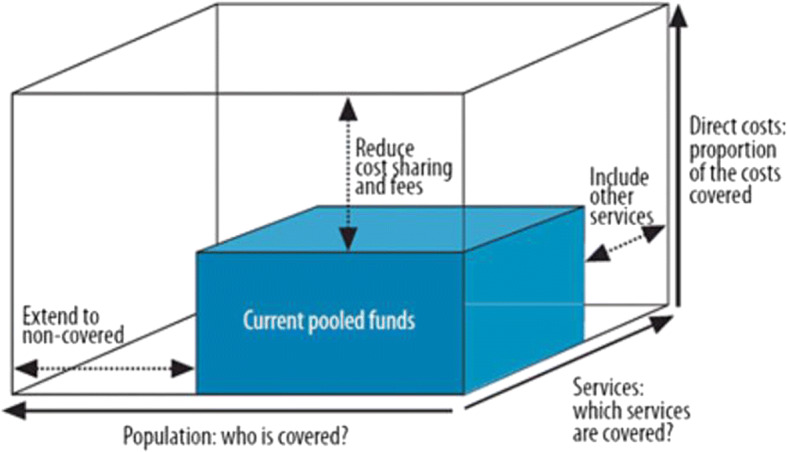

The World Health Organization defines UHC as ‘providing all people with access to needed health services without incurring financial hardship.’ The UHC cube (Fig. 2) provides a useful tool for reframing of the preceding discussion of healthcare access and barriers, as an examination of UHC in Singapore.

Fig. 2.

Three dimensions to consider when moving towards universal coverage (WHO 2010, xv)

Population: Who is Covered?

Singapore excludes migrant workers from elements of its healthcare financing system but provides parallel mechanisms that are intended to ensure access to all required medical services.

Services: Which Services are Covered?

For migrant workers, coverage of emergency medical services is almost universally available, but coverage of non-emergency services (including medically necessary services such as chronic disease care) is variable and highly dependent on employers’ goodwill.

Direct Costs: Proportion of the Costs Covered

Employer responsibility and private insurance ensure robust coverage of costs for some types of care (especially emergency care and work injury inpatient care). Other types of care are excluded or dependent on employers’ goodwill (e.g. chronic disease care, specialist outpatient care).

In sum, Singapore’s national UHC system excludes migrant workers.

Migrant Workers in Singapore and Key Ethical Concepts of the Global UHC Movement

Three key ethical concepts have come to lie at the centre of discourse on the ethics of the global UHC movement: equity, fairness (Ottersen and Norheim 2014), and solidarity (Reis 2016).

Equity

The WHO’s Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage (Ottersen and Norheim 2014; Norheim 2015) conceptualises ‘equity’ as ‘most concerned with equitable access to services regardless of socio-economic status.’

HealthServe’s observations of individual cases and structural patterns of barriers to healthcare access for migrant workers in Singapore suggest potential gaps in realising this value. A first step to addressing this would be detailed, quantitative characterisation of these gaps in access.

Fairness

Norheim (2015) distinguishes the notions of ‘fairness’ from ‘equity’ by granting that although equity may be an aspirational value not immediately achievable given fiscal realities, fairness characterises ethically acceptable trade-offs that occur within these boundaries, on the path to UHC. He defines ‘fair’ health systems as those ‘concerned with the worse-off in terms of health, socio-economic status, or overall well-being.’ This conception echoes the Rawlsian concern for the least advantaged.

Migrant workers in Singapore are an exceptionally disadvantaged population in many dimensions. Although Singapore’s health policy seeks to account for their healthcare needs, significant barriers to access remain. Solutions must focus on the contextual factors recounted above. High costs of healthcare may be relieved by reinstituting subsidised care for migrant workers at government facilities. Employer gatekeeping of healthcare may be countered by streamlining administrative processes like the LoG. And vulnerability to repatriation could be mitigated by regulating recruitment agents.

Solidarity

Solidarity may be defined as ‘shared practices reflecting a collective commitment to carry ‘costs’ (financial, social, emotional or otherwise) to assist others.’ (Prainsack and Buyx 2011), and constitutes the ethical basis of health financing mechanisms such as the redistribution and pooling of funds. Part of the policy rationale for withdrawal of healthcare subsidies for migrant workers in 2008 was the aim of ensuring ‘employers bear the full costs of bringing in foreign workers, rather than impose them on society.’ (Ministry of Manpower 2010). This view draws a clear boundary between Singaporean ‘society’ and ‘foreign workers’ across which solidarity in bearing one-another’s healthcare costs does not reach.

Singapore’s experience with the COVID-19 epidemic, however, has tested this approach. Singapore achieved early success in containment among the local population, followed by a massive surge among migrant workers. This considerably prolonged the required duration of response measures (Au 2020) and triggered government’s rapid pivot to focus on migrant worker dormitories, including provision of free Covid-related medical care by government health facilities (Ministry of Manpower 2020). It is apparent, at least in this time of crisis, that Singapore’s boundaries of solidarity must be redrawn to include migrant workers.

Conclusion

In 2017, international labour migrants were estimated to number 164 million (ILO 2020), and their numbers continue to grow. Migrants (workers and otherwise) are often excluded from national efforts, in the global momentum to achieve UHC (Abubakar et al. 2018; Brolan et al. 2013; Chan and Chia 2017; Onarheim et al. 2018).

Exclusion of migrant workers from any national UHC system calls into question its fundamental ‘universality,’ and challenges the global UHC movement’s ethical premises.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto ML, Dhavan P, et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2606–2654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Jia Wei, Colin Chia, Calvin J. Koh, Brandon W.B. Chua, Shyamala Narayanaswamy, Limin Wijaya, Lai Gwen Chan, Wei Leong Goh, and Shawn Vasoo. 2017. Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Global Health 2 (2): e000213. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ang, Jia Wei, Calvin J. Koh, Brandon W.B. Chua, Shyamala Narayanaswamy, Limin Wijaya, Lai Gwen Chan, Ling Ling Soh, Wei Leong Goh, and Shawn Vasoo. 2019. Are migrant workers in Singapore receiving adequate healthcare? A survey of doctors working in public tertiary healthcare institutions. Singapore Medical Journal. 10.11622/smedj.2019101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Au, Alex. 2016. Work History Survey. Singapore: Transient Workers Count Too. http://twc2.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/work_history_survey_v3.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2020.

- Au, Alex. 2020. The dorms are not the problem.Transient Workers Count Too, 1 May 2020. https://twc2.org.sg/2020/05/01/the-dorms-are-not-the-problem/.

- Bloomberg. 2014. Where do you get the most for your health care dollar? Bloomberg, 18 September 2014. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/infographics/most-efficient-health-care-around-the-world.html.

- Brolan CE, Dagron S, Forman L, Hammonds R, Latif LA, Waris A. Health rights in the post-2015 development agenda: including non-nationals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(10):719–719A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.128173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Joanna, and Dennis Chia. 2017. Practical advice for doctors treating foreign workers. SMA News 49 (2): 18–21. https://www.sma.org.sg/UploadedImg/files/Publications%20-%20SMA%20News/4902/Insight.pdf.

- Chuah, Fiona Leh Hoon, Sok Teng Tan, Jason Yeo, and Helena Legido-Quigley. 2018. The health needs and access barriers among refugees and asylum-seekers in Malaysia: a qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health 17: 120. 10.1186/s12939-018-0833-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. 2014. Health outcomes and cost: A 166-country comparison. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=Healthoutcome2014. Accessed 23 Jul 2020.

- Employment Of Foreign Manpower Act. Revised Edition 2009. 31 July 2009. https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/EFMA1990.

- Fillinger, Tamera, Nicholas Harrigan, Stephanie Chok, Amirah Amirrudin, Patricia Meyer, Meera Rajah, and Debbie Fordyce. 2017. Labour protection for the vulnerable: an evaluation of the salary and injury claims system for migrant workers in Singapore. Singapore: Transient Workers Count Too. http://twc2.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/labour_protection_for_the_vulnerable.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

- Global-is-Asian. 2018. The 3 factors that make Singapore’s healthcare system the envy of the West. https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/gia/article/the-3-factors-that-make-singapore-s-health-system-the-envy-of-the-west. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

- Guinto, Ramon Lorenzo Luis R., Ufara Zuwasti Curran, Rapeepong Suphanchaimat, and Nicola S. Pocock. 2015. Universal health coverage in “One ASEAN”: are migrants included? Global Health Action 8 (1): 25749. 10.3402/gha.v8.25749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harrigan, Nicholas M., and Chiu Yee Koh. 2015. Vital yet vulnerable: Mental and emotional health of South Asian migrant workers in Singapore. Singapore: Lien Centre for Social Innovation, Singapore Management University. https://www.smu.edu.sg/sites/default/files/smu/news_room/Research%20Report_Vital%20Yet%20Vulnerable%20%28FINAL%29.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2020.

- Harrigan NM, Koh CY, Amirrudin A. Threat of deportation as proximal social determinant of mental health amongst migrant workers. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2017;19(3):511–522. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseltine WA. Affordable excellence: the Singapore healthcare story. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020. Labour Migration. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/lang%2D%2Den/index.htm. Accessed 5 May 2020.

- Kaur, Sharon, Paul Ananth Tambyah, Sumytra Menon, See Muah Lee, Shiong Wen Low, and Teck Chuan Voo. 2017. Legal and ethical issues: case study on a migrant worker with a non-work related illness. SMA News 49 (12): 18–21. https://www.sma.org.sg/UploadedImg/1513915975_Full%20PDF.pdf.

- Lee, See Muah. 2012. The patient, his doctor and third parties. SMA News 44 (2): 20–22. http://news.sma.org.sg/4402/CMEP.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

- Lee W, Neo A, Tan S, Cook AR, Wong ML, Tan J, Sayampanathan A, et al. Health-seeking behaviour of male foreign migrant workers living in a dormitory in Singapore. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(1):300. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2013;12(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. 2020. Fee benchmarks and bill amount information lower abdomen, removal of appendix (simple): appendix, various lesions, appendicectomy without drainage, open/laparoscopic (TOSP Code: SF849A / TOSP Table: 3B). https://www.moh.gov.sg/cost-financing/fee-benchmarks-and-bill-amount-information/Details/SF849A%2D%2D1. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2010. Employers are fully responsible for their workers. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-replies/2010/employers-are-fully-responsible-for-their-workers. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2012. Changes to Work Injury Compensation Act. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/announcements/2012/changes-to-work-injury-compensation-act. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2015. Employers must foot foreign workers’ medical bills. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-replies/2015/1222-employers-foot-foreign-workers-med-bills. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2018. Work injury compensation insurance. https://www.mom.gov.sg/workplace-safety-and-health/work-injury-compensation/work-injury-compensation-insurance. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019a. Foreign workers continue to rate working in Singapore favourably in latest survey: pay, living conditions, safety and security commonly cited reasons. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2019/0609-foreign-workers-continue-to-rate-working-in-singapore-favourably-in-latest-survey. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019b. Foreign workforce numbers. https://www.mom.gov.sg/documents-and-publications/foreign-workforce-numbers. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019c. Summary table: labour force. https://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Labour-Force-Summary-Table.aspx. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019d. Work passes and permits. https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019e. Sector-specific rules for work permit. https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-for-foreign-worker/sector-specific-rules. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019f. Medical insurance requirements for foreign worker. https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-for-foreign-worker/sector-specific-rules/medical-insurance. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2019g. Changes to Work Injury Compensation Act in 2020. https://www.mom.gov.sg/workplace-safety-and-health/work-injury-compensation/changes-to-wica-in-2020. Accessed 30 June 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2020. Ministerial statement by Mrs Josephine Teo, Minister for Manpower, 4 May 2020. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/parliament-questions-and-replies/2020/0504-ministerial-statement-by-mrs-josephine-teo-minister-for-manpower-4-may-2020. Accessed 30 June 2020.

- Norheim, Ole Frithjof. 2015. Ethical Perspective: Five unacceptable trade-offs on the path to universal health coverage. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 4 (11): 711–714. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Onarheim, Kristine Husøy, Andrea Melberg, Benjamin Mason Meier, and Ingrid Miljeteig. 2018. Towards universal health coverage: including undocumented migrants. BMJ Global Health 3 (5): e001031. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ottersen, Tygve, and Ole Frithjof Norheim, on behalf of the World Health Organization Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. 2014. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 92 (6): 389. 10.2471/BLT.14.139139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Platt M, Baey G, Yeoh BSA, Khoo CY, Lam T. Debt, precarity and gender: male and female temporary labour migrants in Singapore. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2017;43(1):119–136. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1218756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prainsack, Barbara, and Alena Buyx. 2011. Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. http://nuffieldbioethics.org/project/solidarity/#sthashLenv7FIU.dpuf. Accessed 30 June 2020.

- Rajaraman, Natarajan. 2017. Reply to: the dilemma of medical leave. SMA News, 49 (2): 16–17. https://www.sma.org.sg/UploadedImg/files/Publications%20-%20SMA%20News/4902/Opinion.pdf

- Reis, Andreas A. 2016. Universal Health Coverage – The Critical Importance of Global Solidarity and Good Governance. Comment on “Ethical Perspective: Five Unacceptable Trade-offs on the Path to Universal Health Coverage”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 5 (9): 557–559. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tam WJ, Goh WL, Chua J, Legido-Quigley H. 健康是本钱 - Health is my capital: a qualitative study of access to healthcare by Chinese migrants in Singapore. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2017;16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay, Andrew Epaphroditus Swee Kwang, Kay Wee Choo, and Gerald Choon Huat Koh. 2017. Singapore GP fee survey 2013: a comparison with past surveys. Singapore Family Physician 43 (1): 42–51. https://www.cfps.org.sg/publications/the-singapore-family-physician/article/1084_pdf.

- The Star. 2006. Foreigners’ medical subsidies to be cut.The Star, 12 December 2006. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/regional/2006/12/12/foreigners-medical-subsidies-to-be-cut. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

- WHO . The World Health Report 2000 - Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2014a. Questions and answers on universal health coverage. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/contracting/documents/QandAUHC.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 19 June 2020.

- WHO. 2014b. World Health Assembly resolution 67.14 on health in the post-2015 development agenda. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85535/9789241505963_eng.pdf.

- WHO Office for Europe. 2018. Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European region: No public health without refugee and migrant health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311347/9789289053846-eng.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2020.

- WHO. 2019. Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage - 2019 monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/uhc_report_2019.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2020.