Abstract

Background

Prolactinoma is the most common hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma. Dopamine receptor agonists (DAs) are effective in reducing prolactin levels and tumor mass, but some prolactinoma patients are resistant to DAs. Treating patients with DA-resistant prolactinoma is challenging. In this study, we examined the anti-prolactinoma effect of artesunate (ART), a potential new treatment option for prolactinoma, and its mechanism of action.

Methods

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) and flow cytometry were used to detect the effect of ART on the proliferation, cycle, and apoptosis of rat pituitary adenoma cell line MMQ. The subcellular localization of ART was observed using confocal fluorescence microscopy. The JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) detection and Seahorse assays were used to detect the effect of ART on mitochondrial function. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and Western blot analysis were used to detect the effect of ART on the expression of prolactin (PRL) and apoptosis-related proteins. A mouse xenograft model of prolactinoma was used to detect the inhibitory effect of ART on MMQ in vivo.

Results

ART specifically inhibited MMQ proliferation and PRL synthesis, induced G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in vitro. ART accumulated in the mitochondria of MMQ cells, inhibiting mitochondrial respiratory function and mediating apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. ART also inhibited proliferation and activated the apoptosis of MMQ cells in vivo.

Conclusions

ART has a strong inhibitory effect on prolactinoma both in vitro and in vivo, and its effects rely on high MMP to inhibit mitochondrial metabolism and induce apoptosis. Our results provide evidence for ART as a candidate drug for the treatment of prolactinoma.

Keywords: Artesunate (ART), prolactinoma, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), apoptosis, metabolism

Introduction

Prolactinoma is the most common hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma (1,2). The clinical manifestations include visual field defects and headaches, and/or hyperprolactinemia and hypogonadism, caused by the tumor mass (3). The main objective of clinical therapy is to reduce the tumor volume, return prolactin (PRL) levels to baseline, and restore gonadal function. Ergot-derived dopamine receptor agonists (DAs), including bromocryptine (BRC) and cabergoline (CAB), are the main therapeutic agents for prolactinomas (4,5). Although DAs have been shown to be effective in reducing PRL levels and tumor mass, some prolactinoma patients are resistant to DAs. BRC resistance has been reported in 10–20% of micro-prolactinoma patients and 30% of macro-prolactinoma patients, while 5–10% of micro-prolactinoma patients and 15–20% of macro-prolactinoma patients are reportedly resistant to CAB (6,7). Surgery, drugs, and radiotherapy cannot significantly improve symptoms in DA-resistant patients (8,9). In addition, approximately 20–36% of patients relapse after DA treatment is discontinued (10,11). As a result, new drugs and related treatment strategies are needed to control the disease.

Artesunate (ART), a water-soluble analogue of artemisinin, has a long half-life and low toxicity, and has proven to be a safe and effective treatment for malaria (12). Several studies have shown ART to exert cytotoxic effects on many human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (13-17). Clinical trials have verified the safety and anti-tumor effect of ART. In a small randomized clinical trial for colon cancer, ART was shown to have anti-tumor effects and was generally well tolerated (18). In a patient with advanced prostate cancer, ART temporarily reduced tumor size and prostate-specific antigen levels (19), suggesting that ART may be a potential broad-spectrum anti-tumor drug.

We previously demonstrated that ART inhibited the proliferation of rat pituitary adenoma cell line GH3, induced apoptosis, and reduced hormone synthesis and secretion in vitro (20). ART was also found to reduce serum progesterone and estrogen levels in rats (21). Our previous study showed that low-dose ART combined with BRC synergistically inhibited GH3 and MMQ cell growth, migration, invasion, and extracellular prolactin (22). Although numerous studies have reported that ART induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and regulates tumor-related gene expression, the underlying molecular mechanism by which ART inhibits prolactinoma remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that the anti-prolactinoma mechanism of ART occurs through inhibiting the mitochondrial metabolism and inducing mitochondrial apoptosis. We confirmed the strong anti-prolactinoma effect of ART in the xenograft model, which supports the use of ART as an anti-prolactinoma therapy.

We present the following article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1113).

Methods

Cell lines and mice

The MMQ cell line was purchased from the National Infrastructure of Cell Line Resource sharing platform (Cat#3111C0001CCC000081, Beijing, China), and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco). Rat embryonic fibroblasts (REFs) were extracted from embryonic rat (14 d) as previously described (23), and cultured in DMEM high glucose medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco). REFs cultured to the 3-5th generation were used for experiments. All cultured cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Female nude mice (BALB/c-nu/nu), 4–5 weeks old and weighing about 12.5 g were purchased from the Animal Center of Sun Yat-sen University. All animals were kept pathogen-free with water and food provided ad libitum, and were raised under conditions at 20–26 °C, 40–70% relative humidity, 15 times/h ventilation and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle.

Cell growth and viability

ART was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#A3731, Louis, MD, USA). Ciclosporin A (CsA) was obtained from MedChemExpress (Cat#HY-B0579, NJ, USA). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) was used to measure the effect of ART on cell proliferation. Cells were seeded at a density of 8×103 cells/well in 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. The cells were treated with different concentrations of ART or CsA for varying durations followed by the addition of CCK-8 solution. The cells were incubated with CCK-8 for 2 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a Microplate Reader (Tecan, Sunrise, Switzerland).

Cell apoptosis analysis and cell cycle analysis

Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Keygen, Nanjing, China) was used to quantify cell apoptosis. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and incubated for 24 h before treatment. After 24 and 48 h of ART treatment, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged twice at 1,200 rpm for 3 min. The cells were resuspended in binding buffer and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The apoptotic fraction was analyzed by a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) flow cytometer (Bechman Coulter, Inc. Brea, CA, USA). A cell cycle detection kit (Keygen, Nanjing, China) was used to quantify the cell cycle according to DNA content [Propidium Iodide (PI)] fixation. After treatment with ART for 48 h, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 500 µL of 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 12 h. Prior to cell cycle analysis, the cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 900 µL of DNase-free RNase A solution with 100 µL of PI solution, and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. The distribution of the cellular DNA content was analyzed by FACS, and cell cycle percentage was analyzed by Modfit 4.1 (Verity Software House, Topsham, USA).

JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) detection

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and treated with ART for 12 h. The potential of the mitochondrial membrane was detected by the JC-1 (5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimi-dazolylcarbocyanine iodide) MMP kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). JC-1 is a fluorescent lipophilic carbocyanine dye that has become widely used to measure MMP due to its characteristics of MMP-dependent aggregation. JC-1 monomers (green fluorescence, 488 nm) in the cytoplasm relies on the polarity of the mitochondrial membrane to enter the mitochondria and form a polymer (JC-1 agggregate, red fluorescence, 585 nm). The experiment was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cellular fluorescence values of the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC-A, 488 nm) and propidium iodide (PI, 585 nm) channels were detected by FACS flow cytometer. JC-1 aggregate-positive percentage and JC-1 aggregate–monomer fluorescence ratio were used to quantify MMP.

Mitochondrial staining and laser confocal microscopy

Green fluorescent–labeled ART (G-ART) was obtained from Youjun Yang Research Laboratory (School of Pharmacy, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China). Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to tag cellular mitochondria and Hochest (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was used to label the nucleus. Then, cells were treated with 10 µg/mL G-ART for 45 min, and fluorescence was detected by confocal laser scanning microscope at 1,000× magnification.

Western blot

PARP (Cat#9542S), GAPDH (Cat#5174S), PRL (Cat#6484S), and β-tubulin (Cat#2128S) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CST, Boston, MA, USA). BAX (Cat#AF0120), BCL-2 (Cat#AF6139), and cleaved caspase-3 (Cat#AF7022) were purchased from Affinity Bioscience (Cincinnati, OG, USA). MMQ cells were collected after treatment with ART at different concentrations and treatment durations. Total protein was extracted using RIPA Lysis Buffer (CWBIO, Beijing, China), and the protein concentration was measured using BCA assay kit (CWBIO, Beijing, China). Proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a 0.45 µm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Merck Millipore, USA). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk in PBS with Tween20 at 37 °C for 1 h and incubated at 4 °C overnight with the following primary antibodies: PRL (1:500), PARP (1:1,000), BCL-2 (1:1,000), BAX (1:1,000), β-tubulin (1:3,000), GAPDH (1:3,000), and cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) or HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were visualized with Immobilon ECL Ultra Western HRP Substrate (Merck, Shanghai, China) and Bio-Rad ChemiDoc system (Bio-Rad, Shanghai, China).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The primer sequences were as follows (5'-3'):

PRL forward primer: TGGGGCTATCTTAATGACGGAA

PRL reverse primer: CAGGAGGAGTGTCCCTGCTT

GAPDH forward primer: AGTGCCAGCCTCGTCTCATA

GAPDH reverse primer: GGTAACCAGGCGTCCGATAC

Total RNA was extracted from MMQ cells using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was used as a template for the reverse transcription reaction following the PrimeScript RT Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) instructions. Then, quantitative PCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (HieffTM qPCR SYBR kit; Yesen, Shanghai, China) using CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad).

Seahorse assay

Seahorse XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (XFe96) and Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used to analyze the oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Prior to the assay, cells were treated with ART, CsA, or ART + CsA for 12 h, and then they were planted into the 96-well XF plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well. Test compounds including 10 μM oligomycin solution, 20 μM FCCP solution, and 5 μM ROT/AA, were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The experimental process and protocol for measuring OCR were based on the manufacturer’s instructions (24).

Animal experiments

Mice were subcutaneously injected with 5×106 MMQ cells in 100 µL serum-free DMEM. When subcutaneous tumor growth was visible, the mice were randomly divided into three groups with six nude mice per group. ART was dissolved in 5% NaHCO3 and diluted with saline. The mice were intraperitoneally injected with either 100 or 200 mg/kg of ART or 5% NaHCO3 in saline (control). The tumor volume (V) was evaluated by measuring tumor length (L) and width (W) with Vernier calipers and calculated using the formula: V =0.52 × L × W2. At day 21 post-treatment, all of the mice were euthanized (excessive Barbiturate injection followed by cervical dislocation) and all of the subcutaneous tumors were harvested and weighed in laboratory. The animal experiments comply with the Laboratory animals—General requirements for animal experiment 2018, and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Fifth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (No. 00051). License for use of laboratory animals (SYXK): 2018-0188.

Statistical analysis

All data were obtained from at least three independent experiments, and numerical data in different experimental groups were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistical software version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, when the number of groups was more than two) or Student’s t-test (when the number of groups was two) was used to determine statistically significant differences between groups. A probit regression model was used to calculate the IC50 value. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

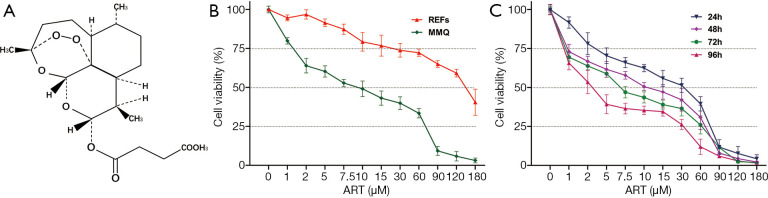

ART specifically inhibited MMQ cell proliferation

The chemical structure of ART is shown in Figure 1A. We performed a dose-response experiment with CCK-8 assay in MMQ and REFs to characterize the tumor suppression efficacy of ART (Figure 1B). ART inhibited the proliferation of MMQ and REF cells, but the IC50 of the REFs was more than 20-fold higher that of the MMQ cells at 48 h (P<0.05). This amounts to approximately 8.3 µM in the MMQ cells and 174.2 µM in the REFs. To determine whether the anti-prolactinoma efficacy of ART is time dependent, we treated the MMQ cells with ART for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. An increased treatment time enhanced the inhibitory effect of ART (P<0.05) (Figure 1C); the IC50 at 24, 72, and 96 h was approximately 16.6, 6.1, and 3.2 µM, respectively.

Figure 1.

ART inhibited MMQ viability in vitro. (A) The chemical structure of ART. (B) Cell viability (%) of MMQ and REFs exposed to increasing doses of ART (48 h, mean ± SD, n=4). ART inhibited cell proliferation of MMQ and REFs in a dose-dependent manner, and the IC50 was 8.3 µM in MMQ but 174.2 µM in REFs; P<0.05. (C) Cell viability (%) of MMQ cells exposed to increasing doses ART for different durations (mean ± SD, n=3). ART inhibited MMQ cell proliferation in a time-dependent manner, and the IC50 at 24, 72, and 96 h was approximately 16.6, 6.1, and 3.2 µM, respectively; P<0.05. ART, artesunate; REF, rat embryonic fibroblasts.

ART treatment induced G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis of MMQ cells

To confirm the anti-prolactinoma effect of ART, FACS was performed to assess the cell cycle stage of MMQ cells after treatment with ART. ART arrested MMQ cells predominantly in the G0/G1 phase and the effect increased as the concentration of ART increased (Figure 2A,B). The percentages of cells arrested at G0/G1 in the control group, 2 µM group, and 8 µM group were 67.3%±1.4%, 78.6%±1.3%, and 84.6%±1.5% (P<0.05), respectively. A minority of MMQ cells were decreased in the G2 (12.7%±2.3%, 10.74%±1.7%, and 7.8%±1.5%; no statistical significance), and S (19.8%±2.3%, 10.6%±1.2%, and 7.87%±0.3%; P<0.05) phases of the cell cycle. Annexin V/PI double staining showed that ART promoted MMQ cell apoptosis in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner. At 24 h, the cell apoptosis rate in the control group, 2 µM group, and 8 µM group was 7.3%±0.1%, 18.3%±0.9%, and 21.1%±0.3% (P<0.05), respectively, while the percentages of apoptotic cells in each group were 7.3%±0.1%, 35.1%±0.7%, and 43.6%±0.8% at 48 h (P<0.05), respectively (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2.

ART treatment induced G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis of MMQ cells. MMQ cells exposed to 2 µM ART, 8 µM ART, and saline (control) for 48 h, respectively, with (A) cell cycle examined by flow cytometry. (B) Quantification of the cell cycle in each group of (A). ART treatment induced G0/G1 phase arrest of MMQ. (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; #, P<0.05, vs. ART 2 µM group; mean ± SD, n=3). MMQ cells were exposed to 2 µM ART, 8 µM ART, and saline (control) for 24 and 48 h, respectively. Graphs showing (C) the cell apoptosis fluorescence map examined by flow cytometry and (D) the quantification of cell apoptosis in each group. ART treatment induced apoptosis of MMQ cells in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner. (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; #, P<0.05, vs. ART 2 µM group; &, P<0.05, vs. ART 24 h group; mean ± SD, n=3). ART, artesunate.

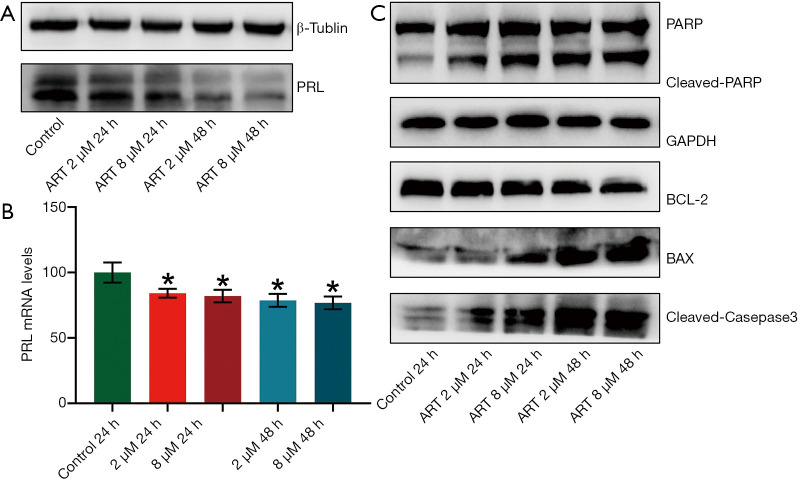

ART inhibited PRL expression by MMQ cells

Western blot analysis and RT-qPCR was performed to detect the PRL protein and mRNA expression in MMQ cells after ART treatment. PRL synthesis decreased after treatment with ART and continued to decrease significantly with increasing treatment concentrations and times (Figure 3A). PRL mRNA levels were decreased after ART treatment (P<0.05), but this reduction was not statistically significant between the treatment groups (Figure 3B). This suggests that ART inhibits the translation of PRL in a time-dependent and dose-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

ART induced apoptosis of MMQ cells via the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway. MMQ cells were treated with the following strategies: saline (control), ART 2 µM for 24 h, ART 8 µM for 24 h, ART 2 µM for 48 h, and ART 8 µM for 48 h; the expression of PRL and apoptosis-related proteins was detected by Western blot. (A) PRL protein expression decreased after treatment with 2 µM and 8 µM ART for 24 h, and continued to decrease significantly in the 48 h group. (B) The PRL mRNA expressions of MMQ exposed to ART detected by qPCR. ART treatment decreased the expression of PRL mRNA. (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD, n=3). (C) ART treatment increased the protein expression of BAX, cleaved caspase 3, and cleaved PARP, and decreased the expression of BCL-2 compared with the control group. ART, artesunate; PRL, prolactin.

ART induced apoptosis of MMQ cells by mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway

We used Western blot to detect apoptosis-related protein changes in MMQ cells treated with different concentrations of ART. As shown in Figure 3C, ART increased the protein expression of BAX and decreased the expression of BCL-2 compared with the control group. In addition, ART increased the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and the proteolytic cleavage of PARP (116 kDa) to its 89 kDa fragment, which is a marker of apoptosis. These findings suggest that ART activates the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis of MMQ cells.

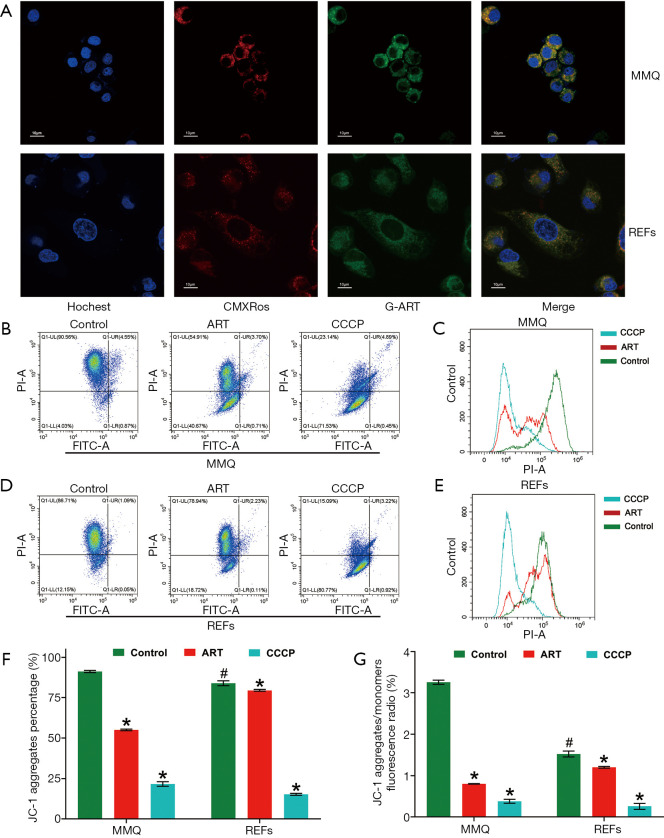

ART specifically accumulated in mitochondria of MMQ

To further clarify how ART kills tumor cells, but not normal cells, we synthesized green fluorescent–labeled ART (G-ART; IC50: 10.0 µM for MMQ, 210.3 µM for REFs) to directly observe the subcellular localization of ART in living cells. We found that ART rapidly accumulated in cytoplasm of MMQ or REFs cells. In MMQ cells, ART was mainly concentrated in mitochondria, while the mitochondrial accumulation was less obvious in REF cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

ART accumulated in mitochondria of MMQ and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). (A) Endogenous location of mitochondria (CMXRos, red), cell nucleus, (Hochest, purple) and ART (green) was detected by laser confocal microscopy (1,000×). In MMQ cells, red fluorescence and green fluorescence had a more obvious colocation phenomenon. (B-G) The ART group was treated with ART 8 µM for 12 h, the CCCP group was treated with CCCP 10 µM for 30 min and used as the positive control. (B) JC-1 fluorescence map of MMQ. (C) Count distribution profile of JC-1 aggregate (PI) in MMQ. (D) JC-1 fluorescence map of REFs. (E) Count distribution profile of JC-1 aggregate (PI) in REFs. (F) MMP is represented as the JC-1 aggregate-positive proportion. ART treatment reduced MMP by 36.3% in MMQ cells and 13.4% in REFs. (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD, n=3). The JC-1 aggregate-positive proportion of the MMQ cells was higher than that of the REFs (#, P<0.05, vs. MMQ control group). (G) MMP is represented as the JC-1 aggregate–monomer ratio. The JC-1 aggregate–monomer fluorescence ratio decreased by 2.4 in MMQ cells but only decreased by 0.3 in REFs (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD, n=3). JC-1 aggregate–monomer ratio of the MMQ cells was higher than that of the REFs (#, P<0.05, vs. MMQ control group). ART, artesunate; REF, rat embryonic fibroblasts.

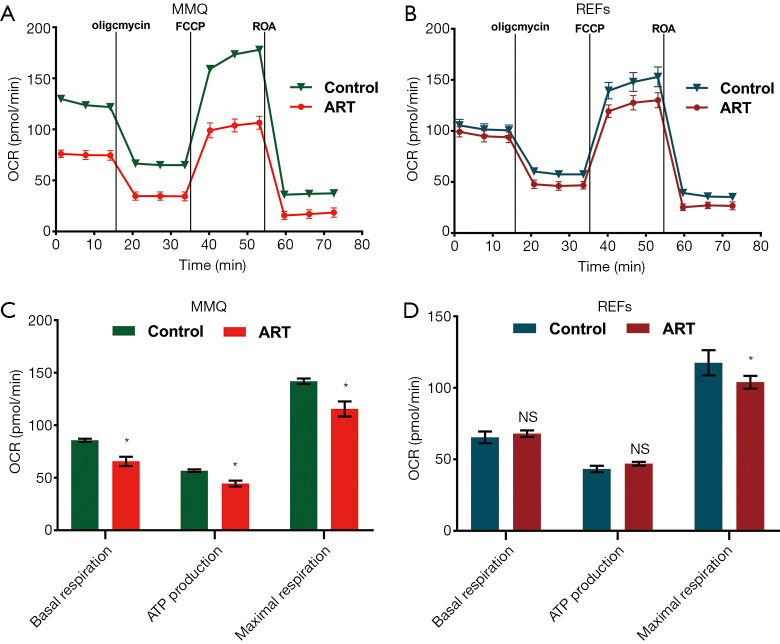

ART reduced MMQ cell mitochondrial inner membrane proton gradient and disrupted metabolism

To examine the effect of ART on mitochondria, we measured the MMP through JC-1 staining and cell flow analysis. After treatment with 8 µM ART, the MMP decreased, but the decrease was more significant in the MMQ cells (Figure 4B,C,D,E). The JC-1 aggregate percentage was reduced by 36.3% in the MMQ cells and 13.4% in the REFs (P<0.05) (Figure 4F). The JC-1 aggregate–monomer fluorescence ratio decreased by 2.4 in the MMQ cells, but only decreased by 0.3 in the REFs (P<0.05) (Figure 4G). Next, we measured the mitochondrial metabolism with the Seahorse assay. The results showed that ART significantly reduced the mitochondrial respiration parameters of the MMQ cells, including basal respiration, ATP production, and maximum respiration capacity (P<0.05) (Figure 5A,B), but had a negligible effect on those of the REFs. There were no statistically significant changes in basal respiration or ATP production in REFs, but there was a slight decrease in maximum respiration capacity (P<0.05) (Figure 5C,D). This suggests that ART inhibits mitochondrial metabolism and disrupts mitochondrial function of MMQ.

Figure 5.

ART disrupted mitochondrial metabolism of MMQ. Graphs showing the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measured in live (A) MMQ and (C) REFs exposed to ART (8 µM, 12 h), and the extracted values for mitochondrial respiration parameters of (B) MMQ cells and (D) REFs. ART treatment inhibited MMQ mitochondrial respiration parameters, including basal respiration, ATP production, and maximal respiration capacity. ART treatment decreased the maximal respiration capacity of REFs, but had no significant effect on basal respiration and ATP-linked respiration (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD, n=3). ART, artesunate; REF, rat embryonic fibroblasts.

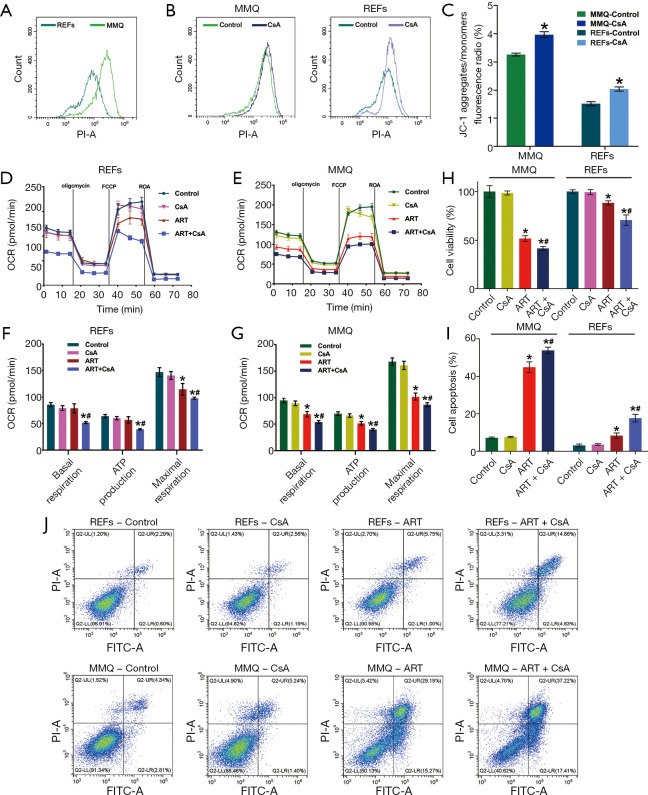

ART effect is associated with high MMP

These results also show that the MMP of the MMQ cells was significantly higher than that of the REFs (P<0.05) (Figure 4F,G, and Figure 6A). To test whether the anti-tumor properties of ART depended on high MMP, we used CsA to increase the MMP (25). CsA treatment effectively increased the MMP of the REFs and MMQ cells (P<0.05) (Figure 6B,C). CsA had no measurable toxicity in cells, but remarkably, in the presence of CsA, the effect of ART on REFs and MMQ has been enhanced, including inhibiting mitochondrial metabolism (P<0.05) (Figure 6D,E,F,G), inhibiting proliferation (P<0.05) (Figure 6H), and promoting apoptosis (Figure 6I,J). These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of ART of cell proliferation may rely on high MMP.

Figure 6.

ART effect is associated with high MMP. (A) Count distribution profile of the JC-1 aggregate (PI) of MMQ and REFs without treatment. MMQ mitochondrial membrane potential was higher than that of REFs. (B) Count distribution profile of JC-1 aggregate (PI) and (C) JC-1 aggregate–monomer ratio of MMQ cells and REFs treated with CsA (2 µM, 30 min). CsA treatment improved the MMP of MMQ and REFs (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD, n=3). MMQ cells and REFs were exposed to 8 μM ART, 2 μM CsA, and 8 μM ART combined with 2 μM CsA (ART + CsA) for 12 h. Graphs show the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measured in (D) REFs and (E) MMQ, and extracted values for basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration, and maximal respiration capacity of (F) REFs and (G) MMQ cells in each group. CsA had no measurable effect on OCR, but in the presence of CsA (2 µM), the ability of ART to inhibit basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration, and maximal respiration capacity was enhanced (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; #, P<0.05, vs. ART group; mean ± SD, n=3). MMQ cells and REFs were exposed to 8 μM ART, 2 μM CsA, and 8 μM ART combined with 2 μM CsA (ART + CsA) for 48 h. (H) Cell viability (%) assay revealed that CsA sensitized MMQ cell and REF toxicity to ART. (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; #, P<0.05, vs. ART group; mean ± SD; n=3). (J) Cell apoptosis fluorescence map and (I) the quantify of cell apoptosis in each group indicated that CsA had no effect in apoptosis, but in the presence of CsA, the proapoptotic activity of ART was enhanced (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; #, P<0.05, vs. ART group; mean ± SD; n=3). ART, artesunate; REF, rat embryonic fibroblasts.

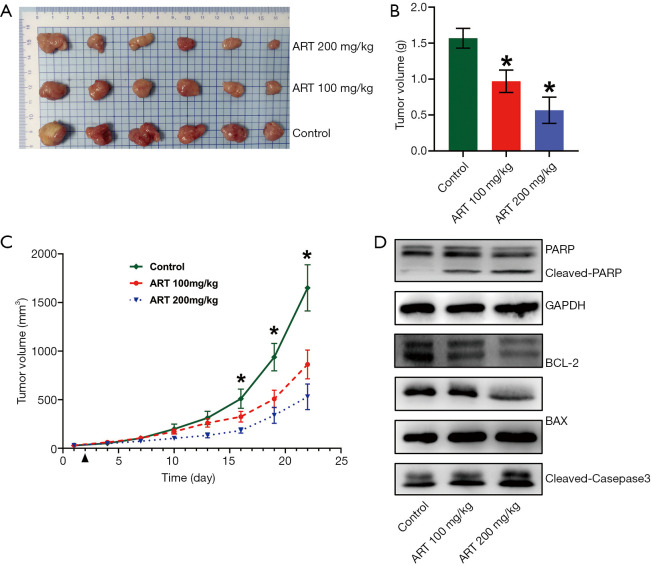

ART showed anti-prolactinomas activity in an MMQ cell xenograft model

To test the efficacy of ART as a potent anti-tumor drug in vivo, BALB/c-nu/nu mice were subcutaneously inoculated with MMQ cells and subsequently treated with ART (100 or 200 mg/kg/day, n=6/group) or saline (control, n=6). Treatment was initiated at day 1 post-grouping. At day 21 post-treatment, all of the mice were euthanized and all of the subcutaneous tumors were harvested and weighed. Compared with the control group, tumor weight in the ART-treated group was significantly reduced (P<0.05) (Figure 7A,B). Tumor growth curve is showing that tumor volume was significantly reduced in mice treated with ART, reaching statistical significance at day 15 post-treatment (P<0.05) (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

ART inhibited the proliferation and induced apoptosis of MMQ cells in vivo. Mice were treated with ART each day (intraperitoneally; IP) beginning 1 day after grouping. (A) The tumors of all mice at day 21 after treatment were harvested and (B) weighed. Tumor weight was significantly reduced in the ART-treated mice (*, P<0.05, vs. control group; mean ± SD; n=6). (C) Tumor growth of MMQ was measured once every 3 days, and tumor growth was significantly reduced in mice treated with ART. (*, P<0.05, one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM; n=6). (D) The PARP, cleaved-PARP, BCL-2, BAX, PRL and cleaved caspase-3 protein expressions of tumor in each group. ART treatment increased the protein expression of BAX, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP, and decreased the expression of BCL-2 and PRL. ART, artesunate; REF, rat embryonic fibroblasts.

ART inhibited PRL synthesis and promoted the apoptosis of MMQ cell xenograft subcutaneous tumors

To elucidate the mechanism of ART inhibition of subcutaneous tumor growth, Western blot analysis was performed to examine apoptosis and associated protein expression levels in tumor tissue. The protein expression levels of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and BAX were increased in the ART-treated group compared to the control group while the level of BCL-2 was decreased (Figure 7D). These findings suggest that ART activates mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in MMQ cells in vivo. Moreover, the levels of PRL protein in the tumor were also significantly reduced in the ART group.

Discussion

DAs have been used as first-line treatment for prolactinomas for 35 years. In the majority of cases, DA treatment normalizes prolactin levels, restores gonadal function and fertility, and significantly reduces tumor size. Currently, for DA-resistant prolactinoma patients, there are no effective therapeutic drugs (6-9). Many studies have attempted to find new effective drugs (26-29), but the specific efficacy and clinical application value need to be further determined. In this study, ART was tested as a potential novel drug for the treatment of prolactinomas. The results showed that ART selectively and significantly inhibited the proliferation of MMQ prolactinoma cells and induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner. A phase II study of adults with falciparum malaria showed that the high mean peak concentration (Cmax) of intravenous ART was approximately 28,558 ng/mL (74 µM), and there were no drug-related adverse events in any of the 28 patients (30). In healthy volunteers, serum concentrations reached 83 mg/ mL (210 µM) and were well tolerated after injection of 8 mg/kg ART (31). In this study, the IC50 value of ART in the MMQ cells was approximately 3.2 µM at 96 h, suggesting that ART has a stronger selective toxicity to prolactinoma cells than to normal cells, and that the corresponding clinical concentration of ART significantly inhibited prolactinoma cell proliferation in vitro. We also further demonstrated ART’s ability to inhibit tumor proliferation and prolactin synthesis in vivo.

Although the anti-tumor effects of ART have been widely reported (14-17,32,33), few studies have elucidated the molecular mechanism by which ART specifically inhibits tumor cells. Recent studies have confirmed that the mitochondrial metabolism is an important mechanism of tumorigenesis (34,35). Mitochondrial metabolism in tumor cells is different from that in normal cells, and multiple mitochondrial functions are modified to maintain cancer cells. Tumor cells have a higher MMP compared to normal cells (36-39), and can thus serve as cancer-specific targets to endow certain compounds or drugs with specific targeting effects (25,39-41). In our study, ART mainly accumulated in mitochondria and significantly inhibited MMQ mitochondrial metabolism, but had a weaker effect on REF cells. This may be attributed to the higher MMP in MMQ cells compared to normal cells. To confirm this, REFs were treated with CsA to increase the MMP prior to treatment with ART. The CsA had no measurable toxicity in the cells, but after CsA-primed REFs were treated with ART, anti-proliferation effects and metabolism inhibition were observed. These results show that ART exerts anti-tumor effects and capitalizes on the high MMP in tumor cells.

Eukaryotic cells must maintain a hyperpolarizing voltage on the mitochondrial inner membrane, otherwise pro-apoptotic agents will be released into the cytoplasm and drive apoptosis (42). Research has shown that BCL-2 protein localized to the outer membrane of mitochondria inhibits apoptosis. BCL-2 forms a heterodimer with BAX, and when the ratio of BAX to BCL-2 is increased, BAX dissociates and causes the release of pro-apoptotic agents into the mitochondria, leading to an increase of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP, which are central to the execution-phase of cell apoptosis (43). In the present study, ART treatment decreased the MMP of the MMQ cells and increased the BAX–BCL-2 ratio, which led to cell apoptosis. Our results are consistent with the previously reported mechanisms of cell tumor apoptosis (14,16,33), demonstrating that ART promotes apoptosis by mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway. However, the specific molecular mechanisms by which ART increases the BAX–BCL-2 ratio and induces a decrease in MMP remain unclear, which need to be further studies.

Conclusions

We here describe a new potential mechanism of ART in inhibiting prolactinoma. ART disrupts mitochondrial function and induces mitochondrial apoptosis by relying on the high MMP in tumor cells. This study provides evidence to support ART as a highly effective, safe, and inexpensive anti-prolactinoma drug.

Acknowledgments

We thank Youjun Yang’s Research Group (School of Pharmacy, East China University of Science and Technology, ShangHai, China) for synthesizing fluorescent labeled Artesunate. We thank AME (http://editing.amegroups.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China Medical [grant number 81773943], Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program [grant number2016008], Science and Technology Research Fund of Guangdong Province [grant number A2018558], National Natural Science Foundation of China for Young Scholars [grant number 81802678], Guangdong Natural Science Foundation Project [grant number 2018A030310107].

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The animal experiments comply with the Laboratory animals - General requirements for animal experiment 2018, and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Fifth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (No. 00051). License for use of laboratory animals (SYXK): 2018-0188.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1113

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1113

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1113

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1113). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Buurman H, Saeger W. Subclinical adenomas in postmortem pituitaries: classification and correlations to clinical data. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;154:753-8. 10.1530/eje.1.02107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, et al. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. Cancer 2004;101:613-9. 10.1002/cncr.20412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colao A, Lombardi G. Growth-hormone and prolactin excess. Lancet 1998;352:1455-61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03356-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:273-88. 10.1210/jc.2010-1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colao A, Savastano S. Medical treatment of prolactinomas. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7:267-78. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellegrini I, Rasolonjanahary R, Gunz G, et al. Resistance to bromocriptine in prolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1989;69:500-9. 10.1210/jcem-69-3-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auriemma RS, Pirchio R, De Alcubierre D, et al. Dopamine Agonists: From the 1970s to Today. Neuroendocrinology 2019;109:34-41. 10.1159/000499470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maiter D. Management of Dopamine Agonist-Resistant Prolactinoma. Neuroendocrinology 2019;109:42-50. 10.1159/000495775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiter D, Delgrange E. Therapy of endocrine disease: the challenges in managing giant prolactinomas. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;170:R213-27. 10.1530/EJE-14-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passos VQ, Souza JJS, Musolino NRC, et al. Long-term follow-up of prolactinomas: normoprolactinemia after bromocriptine with drawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:3578-82. 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colao A, Di Sarno A, Cappabianca P, et al. Withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy for tumoral and nontumoral hyperprolactinemia. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2023-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa022657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.China Cooperative Research Group onqinghaosu and its derivatives as antimalarials. The chemistry and synthesis of qinghaosu derivatives. J Tradit Chin Med 1982;2:3-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Våtsveen TK, Myhre MR, Steen CB, et al. Artesunate shows potent anti-tumor activity in B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol 2018;11:23. 10.1186/s13045-018-0561-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Button RW, Lin F, Ercolano E, et al. Artesunate induces necrotic cell death in schwannoma cells. Cell Death Dis 2014;5:e1466. 10.1038/cddis.2014.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang H, et al. Nrf2 inhibition reverses the resistance of cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer cells to artesunate-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2017;11:254-62. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen P, Gu W, Gong M, et al. Artesunate Decreases beta-Catenin Expression, Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis Resistance in the MG-63 Human Osteosarcoma Cell Line. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;43:1939-49. 10.1159/000484118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou J, Wang D, Zhang R, et al. Experimental therapy of hepatoma with artemisinin and its derivatives: in vitro and in vivo activity, chemosensitization, and mechanisms of action. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:5519-30. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna S, Ganapathi S, Ster IC, et al. A Randomised, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Oral Artesunate Therapy for Colorectal Cancer. EBioMedicine 2014;2:82-90. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michaelsen FW, Saeed MEM, Schwarzkopf J, et al. Activity of Artemisia annua and artemisinin derivatives, in prostate carcinoma. Phytomedicine 2015;22:1223-31. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao ZG, Zhou J, Wang H, et al. Artesunate inhibits cell proliferation and decreases growth hormone synthesis and secretion in GH3 cells. Mol Biol Rep 2012;39:6227-34. 10.1007/s11033-011-1442-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou XE, Zhou HJ. Effects of artesunate on progestrone estrogen content and decidua in rats. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2001;36:254-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Du Q, Mao Z, et al. Combined treatment with artesunate and bromocriptine has synergistic anticancer effects in pituitary adenoma cell lines. Oncotarget 2017;8:45874-87. 10.18632/oncotarget.17437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J. Preparation, culture, and immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2005;Chapter 28:Unit 28.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plitzko B, Loesgen S. Measurement of Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) and Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) in Culture Cells for Assessment of the Energy Metabolism. Bio-Protoc [Internet]. 2018 May [cited 2019 Dec 30]. Available online: https://bio-protocol.org/e2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shi Y, Lim SK, Liang Q, et al. Gboxin is an oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor that targets glioblastoma. Nature 2019;567:341-6. 10.1038/s41586-019-0993-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sosa-Eroza E, Espinosa E, Ramirez-Renteria C, et al. Treatment of multiresistant prolactinomas with a combination of cabergoline and octreotide LAR. Endocrine 2018;61:343-8. 10.1007/s12020-018-1638-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syro LV, Ortiz LD, Scheithauer BW, et al. Treatment of pituitary neoplasms with temozolomide: a review. Cancer 2011;117:454-62. 10.1002/cncr.25413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Liu Y, Gao J, et al. Combination Treatment with Bromocriptine and Metformin in Patients with Bromocriptine-Resistant Prolactinomas: Pilot Study. World Neurosurg 2018;115:94-8. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin SJ, Wu ZR, Cao L, et al. Pituitary Tumor Suppression by Combination of Cabergoline and Chloroquine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3692-703. 10.1210/jc.2017-00627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Remich S, Miller SR, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of intravenous artesunate in adults with uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Kenya: a phase II study. Malar J 2014;13:281. 10.1186/1475-2875-13-281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Cantilena LR, Leary KJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic profiles of artesunate after single intravenous doses at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/kg in healthy volunteers: a phase I study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009;81:615-21. 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Wu N, Wu Y, et al. Artesunate induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis of human retinoblastoma cells by upregulating Kruppel-like factor 6. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:862. 10.1038/s41419-019-2084-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji P, Huang H, Yuan S, et al. ROS-Mediated Apoptosis and Anticancer Effect Achieved by Artesunate and Auxiliary Fe(II) Released from Ferriferous Oxide-Containing Recombinant Apoferritin. Adv Healthc Mater 2019;8:e1900911. 10.1002/adhm.201900911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:8788-93. 10.1073/pnas.1003428107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo JY, Chen H, Mathew R, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2011;25:460-70. 10.1101/gad.2016311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. Growth properties of colonic tumor cells are a function of the intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential. Cancer Res 2006;66:1591-6. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. The intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential of colonic carcinoma cells is linked to the probability of tumor progression. Cancer Res 2005;65:9861-7. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houston MA, Augenlicht LH, Heerdt BG. Stable differences in intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential of tumor cell subpopulations reflect phenotypic heterogeneity. Int J Cell Biol 2011;2011:978583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Bernal SD, Lampidis TJ, Summerhayes IC, et al. Rhodamine-123 selectively reduces clonal growth of carcinoma cells in vitro. Science 1982;218:1117-9. 10.1126/science.7146897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadakavukaren KK, Nadakavukaren JJ, Chen LB. Increased rhodamine 123 uptake by carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1985;45:6093-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinberg SE, Chandel NS. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Chem Biol 2015;11:9-15. 10.1038/nchembio.1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zamzami N, Kroemer G. The mitochondrion in apoptosis: how Pandora's box opens. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2001;2:67-71. 10.1038/35048073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmermann KC, Green DR. How cells die: apoptosis pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:S99-S103. 10.1067/mai.2001.117819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]