Abstract

Background

Severe asthma is a serious condition with a significant burden on patients' morbidity, mortality, and quality of life. Some biological therapies targeting the IgE and interleukin-5 (IL5) mediated pathways are now available. Due to the lack of direct comparison studies, the choice of which medication to use varies. We aimed to explore the beliefs and practices in the use of biological therapies in severe asthma, hypothesizing that differences will occur depending on the prescribers’ specialty and experience.

Methods

We conducted an online survey composed of 35 questions in English. The survey was circulated via the INterasma Scientific Network (INESNET) platform as well as through social media. Responses from allergists and pulmonologists, both those with experience of prescribing omalizumab with (OMA/IL5) and without (OMA) experience with anti-IL5 drugs, were compared.

Results

Two hundred eighty-five (285) valid questionnaires from 37 countries were analyzed. Seventy-on percent (71%) of respondents prescribed biologics instead of oral glucocorticoids and believed that their side effects are inferior to those of Prednisone 5 mg daily. Agreement with ATS/ERS guidelines for identifying severe asthma patients was less than 50%. Specifically, significant differences were found comparing responses between allergists and pulmonologists (Chi-square test, p < 0.05) and between OMA/IL5 and OMA groups (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Uncertainties and inconsistencies regarding the use of biological medications have been shown. The accuracy of prescribers to correctly identify asthma severity, according to guidelines criteria, is quite poor. Although a substantial majority of prescribers believe that biological drugs are safer than low dose long-term treatment with oral steroids, and that they must be used instead of oral steroids, every effort should be made to further increase awareness. Efficacy as disease modifiers, biomarkers for selecting responsive patients, timing for outcomes evaluation, and checks need to be addressed by further research. Practices and beliefs regarding the use of asthma biologics differ between the prescriber's specialty and experience; however, the latter seems more significant in determining beliefs and behavior. Tailored educational measures are needed to ensure research results are better integrated in daily practice.

Keywords: Severe asthma, Biological drug, Belief, Behavior

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; Eos: Eosinophil, IL5; interleukine 5, IgE; Immunoglobulin E, INESNET; INterasma Scientific Network, LABA; long-acting beta2-agonist, OMA; Omalizumab. OMA/IL5, Omalizumab plus anti-IL5 molecule

Introduction

Severe asthma has been defined as “asthma that requires use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) or leukotriene modifier/theophylline for the previous year or systemic corticosteroids for ≥50% of the previous year (GINA steps 4–5 therapy) to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled, or that remains uncontrolled despite this therapy”.1 It affects 5–10% of the total asthma population and imposes a significant burden on health care due to high rates of exacerbations and hospitalization.1 Mortality is a critical issue for these patients, and it is more strongly associated with comorbidities rather than asthma itself.2 Severe asthma is associated with poor quality of life, reduced work capacity, and social isolation.1

For many years maintenance systemic glucocorticoid treatment was the only option for patients with severe asthma. However, this therapy is associated with many well-known side effects including Cushing syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, osteoporosis, cataracts, glaucoma, high blood pressure, and diabetes.3 Omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody was introduced in the early 2000s4 it was found to have glucocorticoid-sparing benefits and a significant reduction in asthma exacerbation rate.5 Although the adverse event profile was comparable to placebo in the original randomized controlled trials,4,5 a recent long-term analysis revealed that omalizumab may be associated with infections, musculoskeletal problems, angioedema, and hormonal disturbances.6 A real-world analysis of a Japanese population showed that the prevalence of side effects may be as high as 30%; however, no placebo has been included.7 Despite contradictory findings on the predictive role of pre-treatment serum IgE levels,8 omalizumab had clear benefit only in allergic asthmatic patients. Recently, novel treatments targeting the IL5 pathway have been introduced. Mepolizumab9, 10, 11 and reslizumab are monoclonal anti-IL5 antibodies that block IL5 in the peripheral blood whereas benralizumab is an anti-IL5 receptor antagonist. These pharmacologic strategies target eosinophilic airway inflammation; however, they differ in their mode of administration, pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic properties, and mechanisms of action. Head-to-head comparisons between anti-IL5 targeted biologics are not available, and data from meta-analyses is not conclusive, making it difficult to select one therapy over another in the management of moderate to severe eosinophilic asthma patients.12,13 Investigating side effects in clinical trials, the most common adverse reactions include nasopharyingitis, headache, and infections, the most serious being anaphylactic reactions.14 Moreover, allergic and eosinophilic inflammation commonly co-exist in severe asthma patients, further complicating clinical decisions for selecting an IL5 biologic versus an anti-IgE agent in these patients.15 Interestingly, recent meta-analyses showed no difference in the efficacy of omalizumab versus anti-IL5 agents13,16 in patients with overlapping phenotypes. Furthermore, the biologic agents provide gains in quality-adjusted survival over standard of care alone; however, the benefit seems to be modeled over a lifetime span at commonly accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds based on a lower than the current market price.17 Although historical studies are available on real-life prescription pattern of omalizumab,18 these originate from the era before anti-IL5 treatment. Since there is considerable overlap between the indication of the 2 groups of drugs (ie, eosinophilia vs. allergy), the current study aimed to review prescribers' choice in real-world settings. The ultimate decision may depend on the physician's specialty training, their previous experience with the management of severe asthma patients, and the use of advanced therapies such as biologics.19 For all of these reasons, and because there is a gap in knowledge providing clear guidance on the use of novel biologics in moderate to severe asthma patients, the choice by clinicians for a specific biological strategy is still largely arbitrary. The purpose of this study was to design and distribute a questionnaire survey in order to ascertain real-world information on the prescribing attitudes of primary care physicians, allergists/clinical immunologists, and pulmonologists for the treatment of severe asthma. We hypothesized that specialty and previous experience with biologic treatments (ie, omalizumab) would be significant factors influencing the selection of an anti-IgE versus an anti-IL5/anti-IL5R specific biologic. Anti IL4/IL13 was not considered since it was not on the market at the time of the survey.

Methods

The development of the questionnaire related to prescribing attitudes involved 10 experts (3 pulmonologists, 3 allergists, 2 internal medicine specialists, and 2 pediatricians) who were asked to generate a list of single or multiple-choice questions in English. Applying a two-rounds Delphi method,20 the experts were asked to rate on two 11-point Likert scales (from 0 = disagree, to 10 = agree) whether they believed each item should be included in the final questionnaire and the degree of agreement with the formulation of the item. In the first round, experts were invited to propose new formulations of items and to suggest new items. Items with median relevance score ≤6 were excluded, as were redundant items, and 5 items were rephrased and were added. In the second Delphi round, experts were asked to re-rate their agreement for each item included in the new list. Items with a relevance score ≥7 were included in the electronic survey. It (appendix 1) was composed 35 items divided into 4 sections: 1) Demography and previous use of biological drugs for severe asthma (Q1-Q7); 2) Behavior and beliefs about clinical issues related to biological treatments (Q8-Q21), 3) Behavior and beliefs about treatment schedules (Q22-Q28), and 4) Behavior and Beliefs about efficacy evaluation (Q29-Q35).

The survey was circulated within the INESNET network (109 members, mass email from the headquarters), Interasma membership (>500 members, mass email from headquarters), contact list of the co-authors, and social media (Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn) between June and September 2018, and it was evaluated by the co-authors. The invitation email contained an encouragement to spread the survey in the membership social network. The outreach, especially on social media, has not been quantified.

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS 23 was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for most of the questions. In addition, we compared answers provided by pulmonologists and allergists as well as physicians with previous experience with only Omalizumab (OMA) vs. those with experience of Omalizumab plus anti-IL5 molecule (OMA/IL5) using chi-square tests. For the latter, a p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demography and use of biological drugs for severe asthma

Out of 302 questionnaires completed, 285 were suitable for analysis. All respondents referred to prescribers of biological drugs for severe asthma. Their demographic characteristics and specialty (Q3) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and specialty of the respondents (n = 285)

| Male, No. (%) | 156 (57,7) |

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 47.7 (7.3) |

| Pulmonologists, No. (%) | 130 (45.6) |

| Allergists, No. (%) | 84 (29.5) |

| Internal medicine specialists, No. (%) | 52 (18.2) |

| Paediatricians, No. (%) | 19 (6.7) |

Prescribers from 37 countries participated in the survey, 77% of them were from Europe; 44% were from high-income countries, 47% from upper middle-income countries, and 8% from lower middle (Q1-2, Fig. 1). In 37.2% of countries, omalizumab was the only available biological treatment for asthma, whereas in 40.7% of countries, both omalizumab and mepolizumab were available. In the remaining 22.1%, benralizumab or reslizumab were available in addition to omalizumab (Q4). 67.4% of physicians had prescribed only omalizumab, while the remaining respondents prescribed omalizumab plus at least one other anti-IL5 biological drug (23.9% mepolizumab, 8.7% other) (Q5-6). 75.4% of the physicians declared that they had bureaucratic limitations in prescribing biological drugs (Q7). 71.2% of prescribers tended to use biological drugs instead of oral glucocorticoids in addition to high doses of ICS/LABA, while 22.8% prescribed biologics for patients on oral glucocorticoids with the aim of tapering their dosage down (Q8).

Fig. 1.

The prevalence of the responders in each country

Behaviors and beliefs about clinical issues related to biological treatments

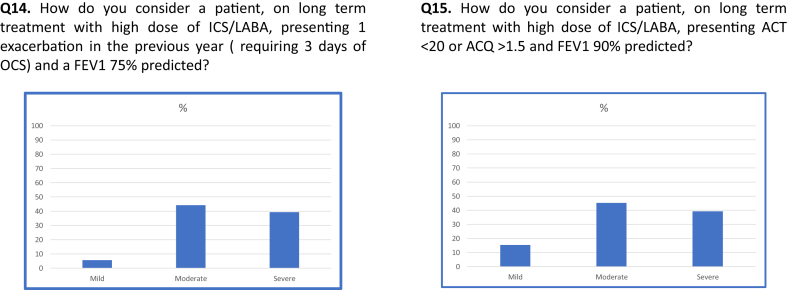

54% of responders believed that the efficacy of oral glucocorticoids predicts the efficacy of the available biological drugs, while 22% disagreed with this opinion, and 24% had not formed an opinion (Q9). 72% of physicians believed that the efficacy of biological drugs exceeds their potential side effects (Q10), 74% felt that they are safer than long term treatment with 5 mg of prednisone (Q11), and 52% considered that the potential adverse events are less than 3 short-term bursts of prednisone (Q12). 69% of participants stated that in a patient with severe asthma, sensitization to perennial allergens, and blood eosinophil >300/mm3, omalizumab would be their first choice (Q13). With respect to the ability to correctly identify disease severity, less than 50% of respondents were able to correctly classify the severity according to the ATS/ERS criteria1 (Q14-15; Fig. 2). Allergic status was considered by the participants as the first clinical parameter on which they would base their therapeutic decisions (69.1%), followed by blood eosinophils (24.9%) and sputum eosinophils (6%) (Q16). 72.2% of respondents considered >300/mm3 blood eosinophils significant while 10.1% aimed for blood eosinophils >150/mm3 and 17.5% aimed >400/mm3. 52.6% considered significant sputum eosinophilia to be >3%, while 8.8% and 38.5% considered that to be >2% and 4%, respectively (Q17-18).

Fig. 2.

ICS/LABA = Inhaled corticosteroid/Long acting beta 2 agonist; OCS = oral corticosteroid; FEV1 = Forced expiratory; Volume in 1 s; ACQ = Asthma control questionnaire; ACT = Asthma control test

Considering all the available biological drugs, 51% of physicians believed that omalizumab and the anti-IL5 drugs are potential disease modifiers; 18% and 19% responded that omalizumab and mepolizumab are the most effective in such cases (Q19). 43% of respondents were aware that IL5 and IL5R receptors have different pharmacological effects, while 38% did not have an opinion (Q20). 53% of participants could not decide which biological drug is faster in ameliorating the clinical status of their patients. Of the remaining, 9.8%, 12.6%, 3.2%, and 21.1% considered benralizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, and omalizumab, respectively, as responding the fastest (Q21).

Behavior and beliefs about treatment schedules

75% of prescribers considered the selection of a specific route of administration as part of the personalization of the patient's treatment plan (Q22-Q26, Table 3) 33% of participants believed that anti IL5 molecules can reduce IgE, while 54% that omalizumab is able to reduce eosinophils; those without an opinion on the above topics were 43% and 16%, respectively (Q27,28).

Table 3.

Comparison of indication, mechanism of action, route of administration and treatment schedule of the four investigated agents.

| Indication | Mechanism of action | Route of administration | Treatment schedule | Tailored vs. predefined dose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab | For patients 6 years of age and older with moderate to severe persistent asthma who have a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen and whose symptoms are inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids | anti-IgE | Subcutenous | Biweekly | Tailored |

| Mepolizumab | For ≥12 years patients add on maintance treatment for patients with severe asthma with eosinophila (>150/μL) | anti-IL5 | Subcutenous | Monthly | Predefined |

| Benralizumab | For ≥12 years patients add on maintance treatment for patients with severe asthma with eosinophila (>150/μL) | anti-IL5Rα | Subcutenous | Monthly for 3 months then bimonthly | Predefined |

| Reslizumab | For ≥18 years patients add on maintance treatment for patients with severe asthma with eosinophila (>400/μL) | anti-IL5 | Intravenous | Monthly | Tailored |

| Remark from the survey | 36.5% considered intravenous and subcutaneous route equally effective, while 23.5% preferred subcutaneous and 9.8% intravenous, 30% did not have an opinion on the topic | 66% preferred monthly administration, 7% bi-weekly; 27% bi-monthly administration. 72% believed that patients prefer monthly, and 22% a bimonthly regime | 54% preferred a tailored dose, 21% a predefined dose, and 11% considered these two approaches equal while 14% had not formed an opinion |

Behavior and beliefs about efficacy evaluation

30% of participants believed that none of the available biologics are effective in inducing a prompt relief of an asthma attack, while 35% of respondents had no opinion on this topic (Q29). Responses to Q30 and Q31 are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency and rate of answers to Q30 and Q31

| Question | Answers | Frequency | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q30. What is your preferred therapeutic option in a severe allergic asthma patient with an incomplete response to Anti-IgE and blood Eos≥150? | To add an Anti IL-5 drug | 80 | 28.1% |

| To switch to an anti IL5 | 111 | 38.9% | |

| Neither of the above | 28 | 9.8% | |

| I have not yet formed an opinion | 66 | 23.2% | |

| Q31. What is your preferred therapeutic option in a severe allergic asthma with an incomplete clinical response to anti-IL5 and Eos ≥150 | To add an Anti IgE drug | 113 | 39.6% |

| To switch to another Anti IL5 | 54 | 18.9% | |

| Neither of the above | 26 | 9.1% | |

| I have not yet formedan opinion | 92 | 32.3% |

Legend: Eos = Eosinophil; IL5 = interleukine 5, IgE = Immunoglobulin E.

Exacerbation rate at 6 months was considered the most important clinical parameter in the assessment of the efficacy of a biological treatment (54%), followed by tapering/stopping of oral steroids (33%) (Q32); 74 out of 285 participants considered exacerbation rate in the following 6 months, tapering/stopping of oral steroid, and ACT or ACQ score the most significant combination of parameters’ in evaluating the efficacy of a biological treatment (Q33). Six months of treatment was considered to be sufficient for judging the efficacy by 53% of physicians, while 26% preferred 3 months, 19% 12 months, and 2% 9 months (Q34).

34.4% of the sample had no opinion about the most effective drug in treating concomitant nasal polyposis, while 9.5% indicated benralizumab, 25.6% mepolizumab, 23.5% omalizumab, 5.3% reslizumab as the best choice in such patients (Q35).

Comparison of responses provided by allergists and pulmonologists

Responses were compared from pulmonologists (n = 130) and allergists (n = 84). Data were also compared from those with dual pulmonology and allergology specialties (n = 48), as well as other specialties (n = 23). A significant difference between allergists and pulmonologists was observed for 4 items. More pulmonologists (42%) than allergists (26%) had not yet developed an opinion on which is the most effective biologic for relieving an asthma attack (χ2 = 12.413; p = 0.030). Regarding responses for incomplete clinical response to anti-IL5 in patients with severe allergic asthma and blood eosinophils >150, more allergists than pulmonologists tended to switch to another anti-IL5 molecule, while 37% of pulmonologists and 42% of allergists would have transitioned to an anti-IgE antagonist (χ2 = 11.769; p = 0.008). More allergists (65%) than pulmonologists (47%) considered asthma exacerbation rate, while more pulmonologists (42%) than allergists (24%) considered tapering or stopping of oral glucocorticoids as the most important clinical parameter for assessing the efficacy of a biologic (χ2 = 8.351; p = 0.039). More pulmonologists (41%) than allergists (21%) had not yet formed an opinion (χ2 = 25.888; p = 0.0001) regarding which biologic was most effective for treating asthma with concomitant nasal polyposis.

Comparison of responses from prescribers with only previous omalizumab (OMA) experience vs those with omalizumab and anti-IL-5 biologic (OMA/IL5) experience

Among the 275 physicians who had experience with omalizumab, 83 also had experience with anti-IL5 biologics while 192 did not. There were 14 significant differences between these two groups.

The OMA/IL5 respondents were less convinced of the predictive effect of oral glucocorticoid efficacy (50% vs 64%), while among OMA respondents there was a higher response rate of those who had not yet formed an opinion (26% vs 9%) (χ2 = 7.358; p = 0.001). OMA/IL5 respondents tended to be more confident that the efficacy of biological drugs was greater than their potential side effects (86.5% vs 69.7); the number of respondents that had not formed an opinion on this topic was lower among the OMA/IL5 group (4% vs 12%) (χ2 = 7.749; p = 0.021). Similarly, OMA/IL5 were more confident that the potential adverse events of biological drugs were less than those of using long-term daily prednisone treatment with prednisone compared to the OMA respondent group (88% vs 69%) (χ2 = 9.343; p = 0.009). OMA respondents were more inclined to consider allergic status as the most important biologic parameter for considering treatment with a biologic in severe asthma patients than OMA/IL5 (76% vs 61%), who considered blood eosinophils as the most important parameter (39% vs 18%) (χ2 = 7.749; p = 0.021).

OMA respondents were more inclined to consider allergic status as the first biological parameter, while OMA/IL5 preferred blood EOS count (χ2 = 13.007; p = 0.001).

The percentage of OMA/IL5 respondents aware that targeting IL5 or IL5R results in different pharmacologic effects was greater than OMA respondents (54% vs 37%), whereas a greater number of OMA respondents had not formed an opinion (44% vs 23%) (χ2 = 7.749; p = 0.021).

Fewer OMA/IL5 (41%) respondents compared to OMA (61%) respondents had not formed an opinion about which biologic was faster in improving clinical status (χ2 = 22.822 p = 0.0001).

57% of OMA/IL5 and 29% OMA respondents believed that intravenous and subcutaneous routes of administration are equally effective, and about 25% of both populations had not formed an opinion on this topic. While OMA/IL5 respondents preferred a tailored dose, OMA respondents preferred a predefined dose, although 20% did not have an opinion on this topic (χ2 = 14.635; p = 0.002).

Bimonthly administration was both the physicians' and (in the physicians' opinion would be the) patient's preferred schedule of treatment interval for OMA/IL5 (42% and 51%) respondents, while monthly administration was preferred among OMA respondents (75% and 73%) (χ2 = 17.570; p = 0.0001).

More than 40% of OMA and OMA/IL5 respondents did not have an opinion on the ability of anti-IL5 drugs to reduce total IgE, although among physicians who had already used anti-IL5 drugs, 36% were not confident, and 18% were confident that these drugs worked in part through this mechanism of action (χ2 = 8.985; p = 0.011).

More OMA/IL5 than OMA respondents believed that none of the available biologics were able to promptly relieve asthma attacks; however, among OMA/IL5 respondents, benralizumab and mepolizumab were considered relievers and among the OMA respondents, omalizumab was considered to achieve this goal (χ2 = 27.240; p = 0.0001).

The preferred therapeutic option in case of incomplete clinical response to an anti-IL5 biologic in a severe allergic asthmatic patient with more than 150/mm3 peripheral eosinophils was to switch or add an anti-IgE drug in 34% of OMA and 57% of OMA/IL5 respondents, respectively, and to switch to another anti-IL5 molecule in 19% of OMA and 18% of OMA/IL5 respondents, respectively (χ2 = 12.921; p = 0.005).

36% of OMA and 29% of OMA/IL5 respondents had yet to form an opinion about the most effective drug in treating concomitant nasal polyposis, while anti-IL5 molecules were preferred among OMA/IL5 and omalizumab among the OMA respondents (χ2 = 24.057; p = 0.0001).

Discussion

Although some biological medications have now been approved for the treatment of severe asthma, there are still some uncertainties and inconsistencies regarding their usage. More importantly, there is no guideline available as to whether omalizumab or anti-IL5/anti IL5R drugs are the best choices in patients who may qualify based on phenotypic characteristics for both medications. To date, there have not been any head-to-head comparison studies conducted between biologicals, and meta-analyses have not shown significant differences between drugs.13,15 Therefore, it would be of interest to explore the prescribers' beliefs and behavior in order to identify if consolidated habits are reflected in research results and to detect areas of uncertainty that need to be the object of future research. According to our knowledge, this is the first study that has surveyed a large number of prescribers regarding their attitudes and approach to using biologics in asthma. In fact, the survey covered 37 countries, though the majority (almost three quarters) of respondents were European. Therefore, other results can be generalized mostly on the European and, to a lesser extent, for American practice. Prescribers are confident that the efficacy of available biological drugs exceeds their potential side effects and the adverse events of a long-term treatment with a low dose of oral glucocorticoid. It seems that further research is needed to evaluate the comparative safety of 3 short-terms burst of oral glucocorticoid/year versus biologics as well their value as disease modifiers. Relevant clinical issues such as differential time-related efficacy in inducing relief of asthma attacks and amelioration of clinical status as well as key parameters, the threshold useful for selecting the treatment and their efficacy needs to be further investigated. It is extremely surprising that about 50% of prescribers fail to adhere to the ATS/ERS definition of severe asthma.1 In particular, identifying “severe asthmatics” patients, those with worse clinical features than those indicated by international guidelines. This behavior likely limits the use of biological treatments, decreasing the individual and social benefits of these treatments.

We found significant differences between allergists and pulmonologists and more importantly between those with and without anti-IL5 experience. More pulmonologists (42%) than allergists (26%) were uncertain of the most effective drug in the case of an asthma attack; more allergists (38%) than pulmonologists (28%) thought that these drugs are equally effective. Interestingly, more allergists than pulmonologists tended to switch to another anti-IL5 drug following an incomplete response to an anti-IL5 treatment, behavior supported by the limited available data.21 A key difference between specialists was the identification of the best therapeutic outcome, as allergists considered exacerbation rate, while pulmonologists aimed at tapering or stopping oral steroids. Both have been represented as primary outcomes in clinical trials.22, 23, 24, 25 A possible reason for the differences between pulmonologists and allergists could be that pulmonologists are more confident in treating asthma attacks and more concerned with the possible long-term side effects of systemic glucocorticoids. Similarly, a more confident approach on the treatment of concomitant nasal polyposis by allergists might be due to their broader experience with this disease.

As expected, significant differences have been observed for 16 responses between omalizumab prescribers who had previous experience with anti-IL5 drugs compared to those who did not. OMA/IL5 users were more confident in answering questions regarding the potential benefit of biologics over their side effects. Most importantly, when assessing a patient, prescribers without anti-IL5 experience preferred assessing the allergic status, which is an indication for the omalizumab but not anti-IL5 treatment. As there is no head-to-head comparison study between the two types of drugs in such a scenario, we have to assume that many practitioners would choose omalizumab as a first-line therapy due to the longer experience with omalizumab. Not surprisingly, specialists with previous experience with anti-IL5 drugs were aware of the potential differences between the anti-IL5 and anti-IL5R drugs. It is known that by blocking IL5R, benralizumab induces natural killer cell-dependent apoptosis of eosinophils.26 Although theoretically this may result in a greater therapeutic effect, a recent meta-analysis failed to prove the superiority of benralizumab over mepolizumab or reslizumab.12 In fact, those who had experience with anti-IL5 therapy did not think that any of the anti-IL5 medications were superior to the others, but they preferred a more precision-based approach for each patient.27,28 More interestingly, doctors with previous anti-IL5 experience did not believe that switching to another anti-IL5 following an incomplete response to anti-IL5 treatment would be beneficial, despite some conflicting evidence.15 Those with previous anti-IL5 experience were confident that anti-IL5 drugs can be beneficial in concomitant nasal polyposis and, in fact, a recent review concluded that omalizumab, mepolizumab, and reslizumab are effective in improving nasal polyposis.29 Previous experience in using different biologics seems to have a greater impact than specialty.

The study has some limitations. Although the survey has been advertised by the Intersama and a professional network (INESNET) as well as social media, the outreach has not been quantified which could limit the interpretation and generalization of the data. Secondly, in 37% of the countries only omalizumab was available, therefore the results of the first part of the survey are influenced by the lack of experience with anti-IL-5 agents. There may be bureaucratic and financial limitations in drug prescription, especially in that more than half of the prescribers were from middle-income countries. A quarter of the prescribers mentioned bureaucratic limitations when prescribing a biologic treatment; however, financial limitations, especially if the drug is fully or partially reimbursed by the insurance, has not been analyzed. Many prescribers believed that the potential side effects of omalizumab and anti-IL5 agents are more favorable than that of oral corticosteroids. However, the anti-IL5 drugs were relatively very new at the conduction of the survey, especially in the middle-income countries, and prescribers may not have come across late-onset side effects. This uncertainty must be considered when evaluating the data.

Interasma Scientific Network suggestions resulting from survey's results

The findings of this survey would be valuable for policy makers and drug companies and may facilitate improved implementation practices and studies to answer the questions identified. Interasma Scientific Network derived the following suggestions from the above-mentioned results:

-

•

Although a large majority of prescribers of biological drugs for asthma treatment are aware that they must be used instead of oral steroids, every effort should be made to further increase awareness and to spread this information to all physicians involved in asthma care.

-

•

While a substantial majority of prescribers believe that the available biological drugs are safer than low dose long-term treatment with oral steroids, a much lower percentage are convinced of their safety in comparison with short high-dose bursts of OCS. Further investigation and educational campaigns are needed.

-

•

The accuracy of prescribers to correctly identify asthma severity according to the ATS/ERS criteria is quite poor, limiting the use of effective molecules in a significant percentage of patients. Every effort should be made to improve physicians' skills.

-

•

Daily practice in the use of biological treatments seems to suggest a disease modifier effect of biological drugs. Further research is needed to increase available knowledge.

-

•

Uncertainty exists concerning the cut-off value of available biomarkers for selecting responsive patients, the outcomes to be evaluated for assessing the efficacy of biological drugs, and the timing of checks. These issues need to be addressed by further research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100441.

Contributor Information

Fulvio Braido, Email: fulvio.braido@unige.it.

Interasma Scientific Network (INES):

Carmen Ardelean, Hector Badellino, Ariel Blua, Antonio Castillo, E. Carpagnano Giovanna, J. Chong-Neto Herberto, F. Daniel Colodenco, Dario Md Colombaro, Jaime Correia-De-Sousa, Fabiano Di Marco, Kunio Dobashi, Rocio Garcia, René Maximiliano Gomez, Olecsandr Gopko, Guillermo Guidos, Martina Hajduk, Joanna Hermanowicz-Salamon, Enrico Heffler, Bulent Karadag, Ali F. Kalyoncu, Metin Keren, Lykorguos Kolilekas, Marcelina Kocwin, Borislava Krusheva, Désirée Larenas Linnemann, Irine Litovchenko, A. Marcipar, L.E. Meza, D. Nedeva, P. Novakova, D. Plavec, S. Popović-Grle, F. Puggioni, L. Pur Oziygit, N. Rodrigez, D. Ryan, I. Ruzsics, N. Scichilone, F. Serpa, P. Steiropoulos, P. Solidoro, M. Turkalj, T. Umanets, C.F. Victorio, J.M. Zubeldia, V. Yachnyk, and M. Zitt

Appendix. INES Collaborators

Ardelean Carmen, Badellino Hector, Blua Ariel, Castillo Antonio, Carpagnano Giovanna E., Chong-Neto Herberto J, Colodenco F, Md Colombaro Dario, Correia-De-Sousa Jaime, Di Marco Fabiano, Dobashi Kunio, Garcia Rocio, Gomez René Maximiliano, Gopko Olecsandr, Guidos Guillermo, Hajduk Martina, Hermanowicz-Salamon Joanna, Heffler Enrico, Karadag Bulent, Kalyoncu Ali F., Keren Metin, Kolilekas Lykorguos, Kocwin Marcelina, Krusheva Borislava, Larenas Linnemann Désirée, Litovchenko Irine, Marcipar Adriana, Meza Luz Elena, Nedeva Denislava, Novakova Plamena, Plavec Davor, Popović-Grle Sania, Puggioni Francesca, Pur Oziygit Leyla, Rodrigez Noel, Ryan Dermot, Ruzsics Istvan, Scichilone Nicola, Serpa Faradiba, Steiropoulos Paschalis, Solidoro Paolo, Turkalj Mirjana, Umanets Tetiana, Victorio Carlos F., Zubeldia Jose M., Yachnyk Vitalii, Zitt Myron

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chung K.F., Wenzel S.E., Brozek J.L. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourdin A., Molinari N., Vachier I., Pahus L., Suehs C., Chanez P. Mortality: a neglected outcome in OCS-treated severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017;50 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01486-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh L.J., Wong C.A., Oborne J. Adverse effects of oral corticosteroids in relation to dose in patients with lung disease. Thorax. 2001;56:279–284. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones J., Shepherd J., Hartwell D. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(Suppl 2):31–39. doi: 10.3310/hta13suppl2/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai T., Wang S., Xu Z. Long-term efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with persistent uncontrolled allergic asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8191. doi: 10.1038/srep08191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Bona D., Fiorino I., Taurino M. Long-term "real-life" safety of omalizumab in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a nine-year study. Respir Med. 2017;130:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi M., Kozawa M., Yoshisue H. Real-world safety and efficacy of omalizumab in patients with severe allergic asthma: a long-term post-marketing study in Japan. Respir Med. 2018;141:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe P.J., Tannenbaum S., Gautier A., Jimenez P. Relationship between omalizumab pharmacokinetics, IgE pharmacodynamics and symptoms in patients with severe persistent allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:61–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavord I.D., Korn S., Howarth P. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortega H.G., Liu M.C., Pavord I.D. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chupp G.L., Bradford E.S., Albers F.C. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:390–400. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busse W., Chupp G., Nagase H. Anti-IL-5 treatments in patients with severe asthma by blood eosinophil thresholds: indirect treatment comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.031. e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iftikhar I.H., Schimmel M., Bender W., Swenson C., Amrol D. Comparative efficacy of anti IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 drugs for treatment of eosinophilic asthma: a network meta-analysis. Lung. 2018;196:517–530. doi: 10.1007/s00408-018-0151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel S.S., Casale T.B., Cardet J.C. Biological therapies for eosinophilic asthma. Expet Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:747–754. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1492540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bousquet J., Brusselle G., Buhl R. Care pathways for the selection of a biologic in severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017;50 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01782-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachef Z., Krishnan A., Mashtare T., Zhuang T., Mador M.J. Omalizumab versus Mepolizumab as add-on therapy in asthma patients not well controlled on at least an inhaled corticosteroid: a network meta-analysis. J Asthma. 2018;55:89–100. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1306548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biologic Therapies for Treatment of Asthma Associated with Type 2 Inflammation: Effectiveness V, and Value-Based Price Benchmarks. 2018. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ICER_Asthma_Draft_Report_092418v1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li P., Kavati A., Puckett J.T. Omalizumab treatment patterns among patients with asthma in the US medicare population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.07.011. e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.https://ginasthma.org/severeasthma/GD-t-tasapg

- 20.Stewart J., O'Halloran C., Harrigan P., Spencer J.A., Barton J.R., Singleton S.J. Identifying appropriate tasks for the preregistration year: modified Delphi technique. BMJ. 1999;319:224–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7204.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee M., Paramo F Aleman, Kjarsgaard M. Weight-adjusted intravenous reslizumab in severe asthma with inadequate response to fixed-dose subcutaneous mepolizumab. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:38–46. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1323OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bel E.H., Wenzel S.E., Thompson P.J. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro M., Zangrilli J., Wechsler M.E. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair P., Wenzel S., Rabe K.F. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2448–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siergiejko Z., Swiebocka E., Smith N. Oral corticosteroid sparing with omalizumab in severe allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:2223–2228. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.620950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan L.D., Bratt J.M., Godor D., Louie S., Kenyon N.J. Benralizumab: a unique IL-5 inhibitor for severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2016;9:71–81. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S78049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menzella F., Bertolini F., Biava M., Galeone C., Scelfo C., Caminati M. Severe refractory asthma: current treatment options and ongoing research. Drugs Context. 2018;5(7):212561. doi: 10.7573/dic.212561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadopoulos N.G., Barnes P., Canonica G.W. The evolving algorithm of biological selection in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020 Jul;75(7):1529–1555. doi: 10.1111/all.14256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kartush A.G., Schumacher J.K., Shah R., Patadia M.O. Biologic agents for the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019 Mar;33(2):203–211. doi: 10.1177/1945892418814768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.