Abstract

Background

In Denmark’s five regions, there is potential inequality in access to device‐aided therapy (DAT) for Parkinson’s disease (PD) based on structural or socioeconomic factors. It is unclear how long DAT is maintained and affects concomitant medication.

Objectives

To investigate access to DAT by comparing the proportion of patients with DBS, subcutaneous apomorphine infusion (SCAI), or levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) in Danish regions 2008–2016 and describe demographics of patients, changes in use of comedication, and maintenance of DAT.

Methods

This work is a retrospective nationwide population‐based registry analysis generated by combining various registries and statistics in Denmark.

Results

From 2008 to 2016, 612 patients started DAT. There were statistically significant differences in the number of patients starting DAT between the Capital Region (99.5 per 1,000) and both Central Jutland (66.6 per 1,000) and North Jutland (70.6 per 1,000; P < 0.05). Among DBS and LCIG patients, respectively, 4% and 42% were aged ≥70 years, 68% and 63% were men (vs. 59% in the general PD population; P < 0.05 for DBS), 73% and 63% had a partner (vs. 62% in the general PD population), and 73% and 71% had a qualifying education (vs. 63% in the general PD population; P < 0.05). Use of PD‐related medication decreased significantly from 4 years before to 4 years after DAT. Eighty‐one percent of the patients who started LCIG, alive 4 years later, had maintained this treatment.

Conclusions

There is unequal access to DAT in the Danish regions, and political and social considerations are warranted to address structural and socioeconomic causes.

Keywords: access inequality, comedication, device‐aided therapy, medication consumption, Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SN. 1 There are ~7,000 PD patients in Denmark. 2 Patients are treated by hospital‐based movement disorder specialists (MDSs) or by private practicing neurologists (PPNs), ~50% each. 3 With progressing disease, symptomatic treatment with levodopa and other dopaminergic treatments may lose its efficacy, and complications, such as motor fluctuations and dyskinesia, may develop. 4 Some patients may benefit from device‐aided therapy (DAT) for PD with either DBS of the STN or continuous infusion therapy with l‐dopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) or apomorphine subcutaneous infusion (SCAI). These types of DAT reduce the fluctuations in motor function and help to stabilize the patients’ ON/OFF periods in the course of a day. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 DBS was introduced in Denmark in the late 1990s, SCAI in 2002, and LCIG in 2004. 10 Generally, DBS is indicated for patients aged <70 years without dementia or psychiatric comorbidity, whereas LCIG and SCAI do not have the same age restrictions and contraindications. 11

Each of the five Danish regions are responsible for providing health care, and patients are automatically enrolled for treatment by neurologists in their own region. DBS is provided as a shared multiregional service and is available in two regions upon referral from MDSs or PPNs in the patients’ region of residence. Infusion therapy with LCIG or SCAI is available in all five regions. Timely identification of the patients who could benefit from DAT, including referral from PPNs to MDSs, can be difficult, given that there is no formal consensus on the definition of advanced PD. 12 , 13 Furthermore, there are differences in the number of both MDSs and PPNs in each region, ranging from 5.6 to 2.7 MDSs per 100 PD patients and 0.76 to 0.15 PPNs per 100 PD patients (Table 1). This allows for potential inequality in access to DAT based on regional structural factors, such as access to DAT‐experienced MDSs, regional waiting list for DAT, and referral by PPNs. Perhaps also patient‐related and socioeconomic factors, such as age, sex, and educational background, could affect a patient’s access to or acceptance of DAT. A study from 2017 demonstrated geographical differences in the use of DBS and LCIG in the 19 regions of Norway, but did not include demographic description of patients. 14 It is unclear whether DAT has secondary benefits, such as diminished use of concurrent medication, and whether the treatment is maintained over time. The aim of the study was to investigate access to DAT in the Danish regions by assessing and comparing the proportion of patients who are prescribed DAT in Denmark and in each of the five Danish regions in the period 2008–2016, and to describe them in terms of age, sex, marital status, and education; also, to assess changes in the concurrent use of PD and non‐PD comedication 4 years before and 4 years after initiation of DAT, as well as maintenance of DAT.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of population and patients with PD, MDSs, and PPNs by Danish region

| Regions East of the Great Belt | Regions West of the Great Belt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Capital Region | Zealand Region | Southern Denmark | Central Jutland | North Jutland |

| Population Q4 (2016) 49 | 1,806,249 | 831,789 | 1,217,170 | 1,302,897 | 587,421 |

| PD population (2015) 16 | 2,111 | 1,064 | 1,843 | 1,576 | 666 |

| No. of MDS (2017) 3 | 119 | 30 | 52 | 51 | 18 |

| No. of MDS/100 patients with PD | 5.6 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| No. of PPNs 3 | 16 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| No. of PPNs/100 patients with PD | 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.15 |

Methods

This is an observational, retrospective, nation‐wide, population‐based registry analysis generated by combining various registries and statistics in Denmark. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was not needed given that register‐based research projects not including biological material need not be notified to the research ethics committee system. The Danish Civil Registration System identifies every citizen with a unique identification number, the CPR number. This facilitates accurate linkage between all Danish national registries. 15 The population of PD patients was identified by the National Patient Register (Landspatientregisteret; LPR) to include patients who were registered as living in Denmark and were aged ≥40 years at any time in the period 2006–2016 and were admitted to a hospital with diagnosis DG20 (PD).

Patients receiving DBS were identified from the population of PD patients in the National Patient Register using the Nordic NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP) codes KAAG20 or KAAG99 whereas patients receiving LCIG and apomorphine were identified from the population of PD patients in the Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes N04BA02 for LCIG (in combination with drug name “Duodopa’), and N04BC07 for apomorphine at any time in the period 2008–2016. Because of the structure of the register, it was not possible to exclude patients using an apomorphine pen (which is not considered DAT), which is why they are also included in the numbers and breakdown of apomorphine patients starting DAT, and why some analyses were performed for DBS and LCIG only.

Registry data were extracted from the LPR, Register of Medicinal Product Statistics (Lægemiddeldatabasen; LMDB), Register of Population Statistics (Danmarks Statistik; BEF), and Education Register (Uddannelsesregisteret; UDDA). Because of rules governing extracts of registry data, there were restrictions in terms of the data that could be accessed; therefore, the variables for marital status, age, and education had to be divided into two categories (single vs. married/living together, age 40–69 vs. age ≥ 70, nonqualifying education vs. qualifying education).

Statistical Analysis

To assess whether there are some PD patients who are more likely to receive DAT, we compared the distribution by sex, age, marital status, and educational background across the patients aged ≥40 years who started DAT in the period 2008–2016 with the corresponding distribution across the general PD population (a special analysis based on the report “Means of Subsistence of Parkinson’s patients 2015” 16 ; see Table 1). Analyses were carried out with the aid of the statistics program SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) on the research computer at Statistics Denmark. A significance level of 5% was generally used. Analyses were performed partly using simple one‐ and two‐way analyses, partly by analysing averages, and partly with the aid of logistic regression analyses, which were also adjusted for several background variables. Logistic regression analyses were used in the analyses to determine whether there were regional differences in the probability of having started DAT in the period 2008–2016, adjusted for sex, age, marital status, and education of the population (the entire Danish population aged ≥40 years was included in these analyses). Contingency table tests are used, that is, classic chi‐square tests (to test whether two ratios are significantly different), and t tests, Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests, and/or Wilcoxon signed rank tests, according to whether the data are normally distributed, and whether the two groups of data are independent (Wilcoxon rank‐sum test) or dependent (Wilcoxon signed‐rank test). The Hosmer‐Lemeshow test was used to test the goodness of fit for the logistic regression models. AbbVie supported the study financially and participated in the study design, interpretation of results, review, and approval of the publication.

Results

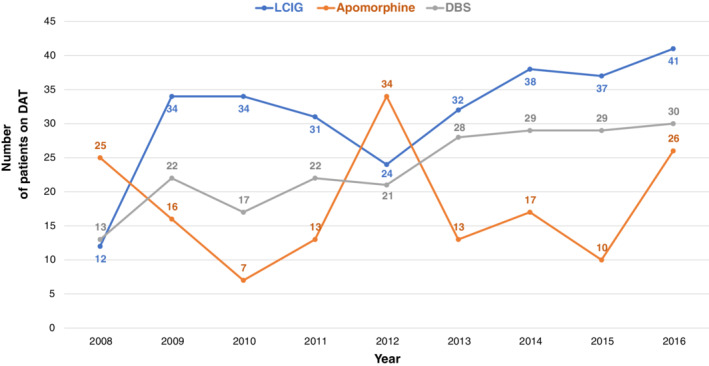

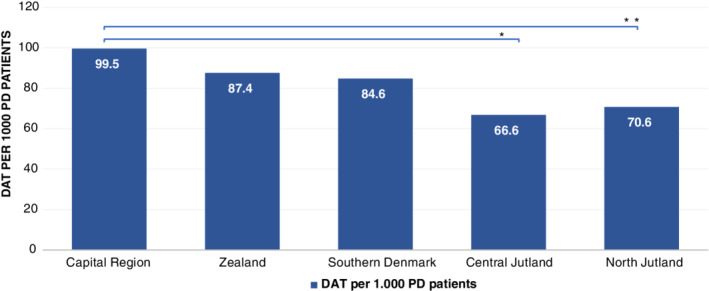

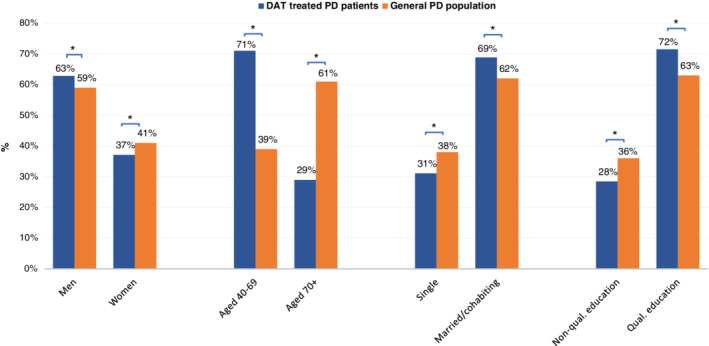

During the period 2008–2016, a total of 612 patients started DAT in Denmark. Two hundred eighty‐three patients started LCIG, 161 started apomorphine (both SCAI and pen), and 211 started DBS (some patients started more than one type of DAT). Throughout the period, there was an annual rising trend in the number of patients starting DAT (Fig. 1). Except for an unexplained outlier in 2012, generally more people started LCIG than DBS and apomorphine per year. To determine whether there are regional differences in the use of DAT, we compared the number of patients starting DAT per 1,000 PD patients in each region. The number of PD patients in each region was determined from a special analysis of the data behind the report “Means of Subsistence of Parkinson’s Patients 2015.” 16 This showed that the number of PD patients in each region were 2,111 in the Capital Region, 1,064 in the Zealand Region, 1,843 in the Southern Denmark Region, 1,576 in Central Jutland, and 666 in North Jutland (Table 1). The number of patients starting DAT per 1,000 PD patients in each region is shown in Figure 2. There were 99.5 per 1,000 in the Capital Region, 87.4 per 1,000 in the Zealand region, 84.6 per 1,000 in Southern Denmark, 66.6 per 1,000 in Central Jutland, and 70.6 per 1,000 in North Jutland. There are statistically significant differences in the number of patients starting DAT per 1,000 PD patients between the Capital Region and both Central Jutland and North Jutland (P < 0.05). When analyzing DBS and LCIG separately, the regional differences were not significantly different for DBS in any region (per 1,000 PD patients: 31.3 in Capital Region, 30.1 in Zealand Region, 28.8 in Southern Denmark, 27.3 in Central Jutland, and 25.5 in North Jutland). The corresponding figures for LCIG (per 1,000 PD patients: 45.9 in Capital Region, 43.2 in Zealand Region, 33.6 in Southern Denmark, 34.3 in Central Jutland, and 34.5 in North Jutland) showed a significant difference between Capital Region and Southern Denmark (P < 0.05). Furthermore, by combining regions east of the Great Belt (Capital and Zealand regions) versus west of the Great Belt (Southern Denmark, Central Jutland, and North Jutland), the results showed a nonsignificant difference for DBS (per 1,000 PD patients: 30.9 east of the Great Belt vs. 27.7 west of the Great Belt), but a significant difference for LCIG (per 1,000 PD patients: 45.0 east of the Great Belt vs. 34.0 west of the Great Belt; P < 0.05; Table 2). To assess whether there are PD patients who are more likely to receive DAT, we compared the distribution by sex, age, marital status, and educational background across the patients aged ≥40 years who started DAT in the period 2008–2016 with the corresponding distribution in the general PD population as described above (see Fig. 3). There were significantly more men, more people aged <70 years, more who have a partner, and more people with a qualifying education among patients who receive DAT, particularly DBS, than among the general PD population:

71% were aged 40 to 69, compared with 39% in the general PD population (P < 0.05). Especially, DBS patients are younger: 96% of DBS patients and 58% of LCIG patients were aged 40 to 69 when they started the treatment (P < 0.05).

63% were men, compared with 59% for the general PD population (P < 0.05). However, the results were only significant for DBS, with 68% men (P < 0.05), whereas LCIG was started in 63% men (not significantly different from the general PD population).

69% had a partner (married/living together), compared with 62% of the general PD population (P < 0.05). However, the results were only significant for DBS, with 73% having a partner (P < 0.05), whereas for LCIG 63% had a partner (not significantly different from the general PD population).

72% had a qualifying education, compared with 63% of the general PD population (P < 0.05). This was significant for both DBS (73%) and LCIG (71%; P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Number of patients on DAT in Denmark per year, 2008–2016.

FIG. 2.

DAT per 1,000 patients with PD per region, 2008–2016. *P < 0.05 when comparing Capital region and Central Jutland; **P < 0.05 when comparing Capital region and North Jutland.

TABLE 2.

LCIG and DBS per 1,000 patients with PD in Danish Regions, 2008‐2016

| Regions East of the Great Belt (n/1,000) | Regions West of the Great Belt (n/1,000) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBS | 30.9 | 27.7 | |||

| LCIG | 45.0 a | 34.0 | |||

| Capital Region | Zealand Region | Southern Denmark | Central Jutland | North Jutland | |

| DBS | 31.3 | 30.1 | 28.8 | 27.3 | 25.5 |

| LCIG | 45.9 b | 43.2 | 33.6 | 34.3 | 34.5 |

aSignificant difference (P < 0.05) for LCIG east versus. west of the Great Belt.

bSignificant difference between the Capital Region and Southern Denmark (P < 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Demographics and socioeconomics of patients with PD receiving DAT, 2008–2016. DAT, device‐aided treatment; ED, education; PD, Parkinson’s disease. *P < 0.05.

Logistic regression analyses demonstrated that even when adjusted for sex, age, and marital status, it makes a significant difference whether a person lives east or west of the Great Belt (P = 0.0126). Persons west of the Great Belt are less likely to have started DAT than people east of the Great Belt, odds ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.817 [0.697–0.957]). Persons in Central Jutland and North Jutland are significantly less likely to have started DAT than persons in the Capital Region, OR Central Jutland (95% CI) = 0.653 (0.517–0.826), OR North Jutland (95% CI) = 0.581 (0.423–0.797). There was no significant difference in the probability of having started DBS according to the part of the country (P = 0.6273) or region (P = 0.5391) a person lives in. However, persons west of the Great Belt are less likely to have started LCIG than persons east of the Great Belt, OR (95% CI) = 0.775 (0.614–0.979) after adjusting for sex and age, whereas the region of residence had no significant impact on the probability of having started LCIG (P = 0.1551).

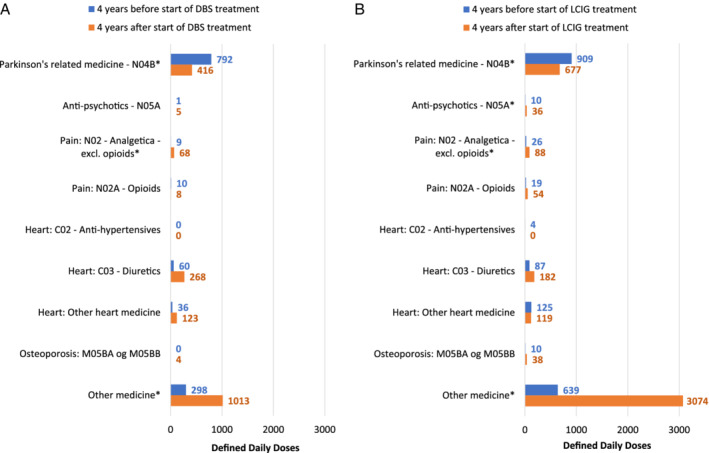

In addition, we investigated the use of PD and non‐PD comedication in Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 4 years before and 4 years after initiation of DAT for the 52 DBS patients and 74 LCIG patients who were alive throughout this period. We found that for both DBS‐ and LCIG‐treated patients, the use of PD‐related medication (ATC code N04B) decreased (from 792 to 416 DDDs for DBS and from 909 to 677 DDDs for LCIG; P < 0.05; Fig. 4). For non‐PD medication, we limited our investigation to the most clinically relevant medicines to treat age‐ and comorbidity‐related complications of PD, such as antipsychotic medicine (ATC code N05A), opioid analgesics (ATC code N02A), nonopioid analgesics (ATC code N02B), cardiovascular medicines (antihypertensives [ATC code C02]), diuretics (ATC code C03), and other heart medicines (which include ATC codes C01, C04, C05, C07, C08, C09, and C10), as well as medication for osteoporosis (ATC code M05BA OG M05BB). For DBS, there was a small but significant increase in the average consumption of nonopioid analgesics (from 9 to 68 DDDs; P < 0.05) and a large increase in “other medicine” (from 298 to 1,013 DDDs; P < 0.05; Wilcoxon’s signed‐rank test). For LCIG, there was a small but significant rise in the average consumption of antipsychotic medicine (from 10 to 36 DDDs; P < 0.05) and nonopioid analgesics (from 26 to 88 DDDs; P < 0.05) and a large increase in “other medicine” (from 639 to 3,074 DDDs; P < 0.05; Wilcoxon’s signed‐rank test).

FIG. 4.

Consumption of medication for patients receiving a) DBS and b) LCIG. DBS, deep brain stimulation; LCIG, levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel. *P < 0.05.

Given that DAT may lose efficacy over time or cause adverse events that could lead to discontinuation, we wanted to calculate the proportion of patients who maintained the same type of DAT 4 years after they initiated it. However, these data were only available for LCIG, where we found that 81% of the patients who started that treatment, and were alive 4 years later, had continued it.

Discussion

The results demonstrate an increasing use of DAT in Denmark over the years from 2008 to 2016. However, there are variations between regions, with the Capital Region treating more patients with DAT per 1,000 PD patients than other regions. This could be attributable to variations in number of MDSs and PPNs in the regions. Additionally, developments over the last decade within the field of neurology have required a shift of resources to other functions (e.g., stroke 17 and multiple sclerosis 3 ), rendering regions with fewer neurologists even more vulnerable in terms of also providing highly specialized DAT. We did not investigate access to neurosurgery in the two regions providing DBS, or access to gastroenterologist in the five regions providing LCIG, which could contribute to differences in waiting list and thereby affect patient access to DAT. Individual MDSs’ experience with DAT, or local practices for identifying patients, may also generate a practice of more DAT in some regions than in others. Finally, regions vary in geographical size, infrastructure, and access to public transportation, which could make a referral to a tertiary MDS center unattractive for some patients in rural areas.

We found that patients who initiate DAT, particularly DBS, are younger than the general PD population. This is not surprising, given that age ≥ 70 is generally, 12 and in Denmark, 11 considered a contraindication for DBS. Significantly more male than female PD patients (68% vs. 32%) received DBS than what was accounted for by a higher prevalence of PD in men. This sex difference was not found for LCIG. Meta‐analyses from 2000 and 2011 found similarly that neurosurgery for PD is roughly twice as frequent in male than in female patients, 18 , 19 and a recent American retrospective analysis of 3,251 PD patients found a male/female sex distribution of 62%/38%, but more disparity in the distribution of referred (76%/24%; n = 207) and DBS‐treated (77%/23%; n = 100) patients. 20 Patients are often reluctant about accepting referral for DAT, 21 , 22 but few studies have investigated the reasons for men and women separately. One study found that whereas male patients tended to demand or accept DBS when offered, female patients expressed stronger fear of complications. However, the study also found that clinicians were more willing to refer demanding men, rather than demanding women, to DBS. 23 Another study found that neurologists overestimated surgical complications related to DBS and tended to overestimate the reluctance of their patients to undergo DBS. 24 This study did, however, not evaluate the responses by sex. Given that female PD patients more often than men present with tremor and have shorter time to develop wearing off and dyskinesia, 25 they are equally good candidates for DBS. Taken together, a difference in male and female PD patients’ health care–seeking behavior should be considered by neurologists and neurosurgeons in order to not inadvertently preclude any PD patient from their best treatment option.

We found that more DBS patients have a partner, compared with the general PD population, and that having a partner was significantly associated with being treated with DBS, but not with LCIG. This could be partly explained by the younger, and comparatively healthier, DBS patients not having lost their partner to, for example, death or divorce. Also, the publicly funded home nurses in Denmark are trained to deal with the pumps and tubes associated with LCIG and SCAI, and the companies behind LCIG and SCAI offer support in case of acute technical problems. For DBS, there is not a similar support system, and with the increasing use of rechargeable batteries, an MDS might also take into consideration whether the patient has a partner or close relative.

It is well established that lower socioeconomic status, including education, is associated with poorer access to and outcome of health care in chronic conditions including PD, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 even in Denmark. 30 The reasons may include a combination of behavioral, psychological, material, and social mechanisms. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 Similarly, we found in our study that being a PD patient with lower education level was significantly associated with less likelihood of starting DAT, compared to PD patients with a higher education. One study on the decision‐making process for PD patients found that, on a number of parameters, PD patients showed very diverse information needs on DAT, 37 supporting the notion that communicating and choosing treatments require an individualized approach. 38 However, more research is needed on the role and intersection of sex and socioeconomic factors in the decision‐making process of DAT in patients with advanced PD.

To analyze the use of comedications, we limited our investigation to the most clinically relevant medicines to treat age‐ and PD‐related comorbidities. For both DBS and LCIG patients, there was significantly less use of PD‐related medication from 4 years before DAT to 4 years after, more so for DBS patients. Other studies have demonstrated substantial reductions in dose of dopaminergic treatment up to 5 years after DBS, 39 and of 119 patients starting LCIG monotherapy, 57% remained on LCIG monotherapy after 24 months. 40 On the other hand, we found that the consumption of some other medicines increased, which could be explained by the fact that, over these 8 years, it would be expected that age‐ and disease‐related comorbidities, warranting more medical treatment, would occur. The difference between DBS and LCIG patients in change in drug use over the period, including the increase in antipsychotic medication for LCIG, is presumably attributed to selection bias with DBS patients being younger and with fewer comorbidities than LCIG patients when starting treatment. 41 An Italian group found that PD patient drug use increases with disease duration, severity, and patient age, with >80% of the patients receiving non‐PD medication, 42 primarily for hypertension, sleep disturbances, anxiety states, depression, hallucinations, and pain in joints. PD patient drug use exposes them to risk of drug‐drug interactions attributed to polypharmacy. A recent prospective study on 127 PD patients with advanced PD, including some with DAT, found that interactions most frequently involved central nervous system–active substances (mainly opioids, neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants) with l‐dopa, followed by pramipexole and rotigotine. 43 The fact that we found that PD‐related medications diminished up to 4 years after DAT, despite a presumed progression of disease, is therefore clinically relevant, given that it could diminish the risk of harmful drug interactions. 44

It is of interest to patients whether the prescribed treatment is maintained over time. For LCIG, we found that 81% of patients who were alive after 4 years had continued treatment. This is similar to an integrated safety analysis from clinical trials, where patients had a median exposure to LCIG of 911 days (range, 1–1,980 days), 45 which found an overall rate of discontinuation because of adverse events of 17%. We had in our analysis only included those who were alive after 4 years and are thus excluding those who died during the study. As mentioned above, we could not obtain similar data for DBS or apomorphine. However, a retrospective analysis of 125 patients found a mean duration of SCAI of 32.3 ± 31.9 months, ranging up to 139 months. Three‐quarters of patients discontinued within the first 4 years. 46 Hardware used for DBS is rarely removed, except in cases of infection. 47 A systematic review from 2017 found the incidence of infection and skin erosions for DBS in PD to be 5.84%, 45% of which resulted in partial or entire hardware removal. 48

The study demonstrates that even in a country with free public health care barriers exist to receiving DAT, resulting in unequal access depending on region of residence. In addition, various demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as sex, education level, and having a partner, may affect the choice of being prescribed or accepting DAT, contributing to a discussion on developing equity‐oriented practices, both political and social, about access to health care resources. Also, objective criteria for identifying patients eligible for DAT, and easy access to a variety of balanced and thorough information on the treatments to patients and their caregivers, could help minimize these barriers, although more research is needed on factors affecting different patients’ decision‐making processes on DAT. In addition, the study shows that use of PD‐related medicines decreases from 4 years before to 4 years after DAT, but that the use of some other non‐PD‐related medicines increases. Finally, 81% of patients alive after 4 years maintained LCIG treatment.

There are limitations to our study. Although the identification of patients in the registry through the CPR system minimizes selection bias and allows for true identification of all relevant patients, it is important to note that the registries did not allow for distinction between the apomorphine pen (a rescue therapy) and the apomorphine pump, thus overestimating the actual numbers of patients in DAT. It is the clinicians’ professional experience that ~15% to 20% of the apomorphine treatment in this analysis was pen treatment. Because of protection of personal data, it was only possible to obtain binary data related to demographics, and not, for example, average age for the populations.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

T.H.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3B

E.D.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3B

H.E.H.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

A.W.B.: 1A, 1C, 2C, 3B

U.S.L.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3A, 3B

K.P.D.: 1A, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: This study is based on nonbiological anonymous data from registries and has therefore not been reviewed by an ethical committee nor was informed consent necessary to obtain. The external vendor, COWI, has received acceptance from The Danish Data Protection Agency to extract data from the registries. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: Financial support for the study was provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the study design, interpretation of results, review, and approval of the publication. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: T.H. has received honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, Brittania Pharmaceuticals, Zambon, and Lundbeck. E.H.D. has received honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, Grünenthal, and UCB. K.P.D. has received honoraria for lectures from AbbVie and Norgine B.V. A.W.B. is a former employee of AbbVie. U.S.L. is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stocks or stock options.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Niels Anker of COWI for procuring data and providing statistical analyses. Funding was provided by AbbVie.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Starhof C, Anker N, Henriksen T, et al. Dependency and transfer incomes in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Dan Med J 2014;61:A4915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decide. Facts on capacity and treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease in Denmark. 2019. Available from: http://decide.nu/wp-content/uploads/fakta-om-parkinsonbehandling.pdf. Accessed on 15 June 2020.

- 4. Encarnacion EV, Hauser RA. Levodopa‐induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: etiology, impact on quality of life, and treatments. Eur Neurol 2008;60:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antonini A, Moro E, Godeiro C, et al. Medical and surgical management of advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2018;33:900–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montgomery EB, Jr. , Gale JT. Mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008;32:388–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deuschl G, Schupbach M, Knudsen K, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus at an earlier disease stage of Parkinson’s disease: concept and standards of the EARLYSTIM‐study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Odin P, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double‐blind, double‐dummy study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson’s disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:749–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karlsborg M, Korbo L, Regeur L, et al. Duodopa pump treatment in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. Dan Med Bull 2010;57:A4155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danmodis. Parkinson’s disease. A clinical guideline, 2nd edition [PDF]. Danish Society for Movement Disorders; 2011. [updated 2011]. 2nd edition [Clinical guideline]. Available from: https://neuro.dk/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2012/09/Parkinsons_sygdom_Klinisk_Vejledning_2011.pdf. Accessed on 21 November 2019.

- 12. Antonini A, Stoessl AJ, Kleinman LS, et al. Developing consensus among movement disorder specialists on clinical indicators for identification and management of advanced Parkinson’s disease: a multi‐country Delphi‐panel approach. Curr Med Res Opin 2018;34:2063–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fasano A, Fung VSC, Lopiano L, et al. Characterizing advanced Parkinson’s disease: OBSERVE‐PD observational study results of 2615 patients. BMC Neurol 2019;19:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ezat B, Pihlstrom L, Aasly J, et al. Use of advanced therapies for Parkinson’s disease in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2017;137:619–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anker N. Means of subsistence of Parkinson’s disease patients 2015. 2016. Available from: https://www.parkinson.dk/sites/default/files/pdf-filer/Cowi%202016.pdf. Accessed on 15 June 2020.

- 17.Danish Stroke Association. National guideline for intravenous thrombolytic treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. 2016 [updated February 2016]. Version 2. Available from: http://www.dsfa.dk/wp-content/uploads/Nationale_retningslinier_trombolyse_2016_110216.pdf. Accessed 25 September 2019.

- 18. Hariz G, Hariz MI. Gender distribution in surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2000;6:155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hariz GM, Nakajima T, Limousin P, et al. Gender distribution of patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with subthalamic deep brain stimulation; a review of the 2000–2009 literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shpiner DS, Di Luca DG, Cajigas I, et al. Gender disparities in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Neuromodulation 2019;22:484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wachter T, Minguez‐Castellanos A, Valldeoriola F, et al. A tool to improve pre‐selection for deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 2011;258:641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim MR, Yun JY, Jeon B, et al. Patients’ reluctance to undergo deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;23:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamberg K, Hariz GM. The decision‐making process leading to deep brain stimulation in men and women with Parkinson’s disease—an interview study. BMC Neurol 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lange M, Mauerer J, Schlaier J, et al. Underutilization of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease? A survey on possible clinical reasons. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017;159:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Picillo M, Nicoletti A, Fetoni V, et al. The relevance of gender in Parkinson’s disease: a review. J Neurol 2017;264:1583–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uccheddu D, Gauthier AH, Steverink N, et al. Gender and socioeconomic inequalities in health at older ages across different european welfare clusters: evidence from SHARE data, 2004–2015. Eur Sociol Rev 2019;35:346–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Korda RJ, Paige E, Yiengprugsawan V, et al. Income‐related inequalities in chronic conditions, physical functioning and psychological distress among older people in Australia: cross‐sectional findings from the 45 and up study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Willis AW, Schootman M, Kung N, et al. Disparities in deep brain stimulation surgery among insured elders with Parkinson disease. Neurology 2014;82:163–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan AK, McGovern RA, Brown LT, et al. Disparities in access to deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson disease: interaction between African American race and Medicaid use. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ullits LR, Ejlskov L, Mortensen RN, et al. Socioeconomic inequality and mortality—a regional Danish cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muennig P, Kuebler M, Kim J, et al. Gender differences in material, psychological, and social domains of the income gradient in mortality: implications for policy. PLoS One 2013;8:e59191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skalicka V, van Lenthe F, Bambra C, et al. Material, psychosocial, behavioural and biomedical factors in the explanation of relative socio‐economic inequalities in mortality: evidence from the HUNT study. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:1272–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995;Spec No:80–94. [PubMed]

- 34. Bartley M. Health Inequality: An Introduction to Concepts, Theories and Methods, 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA 2010;303:1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schrijvers CT, Stronks K, van de Mheen HD, et al. Explaining educational differences in mortality: the role of behavioral and material factors. Am J Public Health 1999;89:535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nijhuis FA, van Heek J, Bloem BR, et al. Choosing an advanced therapy in Parkinson’s disease; is it an evidence‐based decision in current practice? J Parkinsons Dis 2016;6:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weernink MG, van Til JA, van Vugt JP, et al. Involving patients in weighting benefits and harms of treatment in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, et al. Five‐year follow‐up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1925–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poewe W, Bergmann L, Kukreja P, et al. Levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel monotherapy: GLORIA Registry demographics, efficacy, and safety. J Parkinsons Dis 2019;9:531–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dafsari HS, Martinez‐Martin P, Rizos A, et al. EuroInf 2: subthalamic stimulation, apomorphine, and levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2019;34:353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leoni O, Martignoni E, Cosentino M, et al. Drug prescribing patterns in Parkinson’s disease: a pharmacoepidemiological survey in a cohort of ambulatory patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002;11:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muller‐Rebstein S, Trenkwalder C, Ebentheuer J, et al. Drug safety analysis in a real‐life cohort of Parkinson’s disease patients with polypharmacy. CNS Drugs 2017;31:1093–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Csoti I, Herbst H, Urban P, et al. Polypharmacy in Parkinson’s disease: risks and benefits with little evidence. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2019;126:871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lang AE, Rodriguez RL, Boyd JT, et al. Integrated safety of levodopa‐carbidopa intestinal gel from prospective clinical trials. Mov Disord 2016;31:538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Borgemeester RW, Drent M, van Laar T. Motor and non‐motor outcomes of continuous apomorphine infusion in 125 Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;23:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Okun MS. Deep‐brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jitkritsadakul O, Bhidayasiri R, Kalia SK, et al. Systematic review of hardware‐related complications of deep brain stimulation: do new indications pose an increased risk? Brain Stimul 2017;10:967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Denmark Statistics. Danish population Q4 2016. StatBank Denmark: Statistics Denmark; 2019. [Google Scholar]