Abstract

Neobavaisoflavone (NBIF), a phenolic compound isolated from Psoralea corylifolia L., possesses several significant biological properties. However, the pharmacokinetic behaviors of NBIF have been characterized as rapid oral absorption, high clearance, and poor oral bioavailability. We found that NBIF underwent massive glucuronidation and oxidation by human liver microsomes (HLM) in this study with the intrinsic clearance (CLint) values of 12.43, 10.04, 2.01, and 6.99 μL/min/mg for M2, M3, M4, and M5, respectively. Additionally, the CLint values of G1 and G2 by HLM were 271.90 and 651.38 μL/min/mg, respectively, whereas their respective parameters were 59.96 and 949.01 μL/min/mg by human intestine microsomes (HIM). Reaction phenotyping results indicated that CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 were the main contributors to M4 (34.96 μL/min/mg), M3 (29.45 μL/min/mg), M3 (13.16 μL/min/mg), and M2 (63.42 μL/min/mg), respectively. UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 mainly catalyzed the formation of G1 (250.87 μL/min/mg), G2 (438.15 μL/min/mg), G1 (92.68 μL/min/mg), and G2 (1073.25 μL/min/mg), respectively. Activity correlation analysis assays showed that phenacetin-N-deacetylation was strongly correlated to M3 (r = 0.860, p = 0.003) and M4 (r = 0.775, p = 0.014) in nine individual HLMs, while significant activity correlations were detected between paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation and M2 (r = 0.675, p = 0.046) and M3 (r = 0.829, p = 0.006). There was a strong correlation between β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide and G1 (r = 0.822, p = 0.007) and G2 (r = 0.689, p = 0.040), as well as between propofol-O-glucuronidation and G1 (r = 0.768, p = 0.016) and G2 (r = 0.860, p = 0.003). Moreover, the phase I metabolism and glucuronidation of NBIF revealed marked species differences, and mice are the best animal model for investigating the metabolism of NBIF in humans. Taken together, characterization of NBIF-related metabolic pathways involving in CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, 2C19, and UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9 are helpful for understanding the pharmacokinetic behaviors and conducting in-depth pharmacological studies.

Keywords: Neobavaisoflavone, Cytochromes P450, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, Species difference, Metabolic pathway

1. Introduction

Neobavaisoflavone (NBIF) is one of the most abundant bioactive compounds isolated from the seeds of Psoralea corylifolia L., which are widely used to invigorate the kidneys and strengthen Yang in clinical practices using herbal medicines and dietary supplements [1]. NBIF accounts for 0.1–0.9% of the dried seed weight [2,3]. Numerous studies have examined NBIF in the fields of pharmacology to study the inhibition of platelet aggregation (IC50 = 2.5 μM) [4], anti-inflammatory activity [5], enhancing tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer cells [6], activation of both estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes [7], and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities (IC50 = 27.7 μM) [8]. Additionally, NBIF is considered a potential anabolic agent for treating bone loss-associated diseases [9]. A combination of NBIF and TRAIL may be a new therapeutic strategy for treating TRAIL-resistant glioma cells [10].

These important biological activities have attracted attention in related metabolism and pharmacokinetics studies. Our previous studies indicated that NBIF mainly underwent oxidization, hydroxylation, hydration, cyclization, epoxidation, sulfation, and glucuronidation reactions in rats [11], while hydroxylation, hydration and epoxidation reactions should be the main biotransformations in rat intestinal microflora [12]. Additionally, pharmacokinetic studies reported that NBIF was quickly absorbed into the rat plasma with a maximal plasma concentration of less than 18.37 ng/mL after oral administration of Psoralea corylifolia extracts or P. corylifolia-containing prescriptions [13-15]. NBIF also readily penetrated the blood brain barrier and accumulates in the brain [15].

In contrast, NBIF exhibited significant inhibitory effects on drug-metabolizing enzymes and nuclear receptors. For example, NBIF displayed obvious inhibitory effects on UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) and human liver microsomes (HLM) with IC50 values of 2.42 and 2.25 μM, respectively [16]. Additionally, NBIF noncompetitively inhibits the activities of human carboxylesterase 1 [17] and human carboxylesterase 2 (IC50 = 6.39 μM) [18]. NBIF showed weak inhibition and selectivity of human monoamine oxidase-A and -B (IC50 = 66.52 and 77.29 μM, respectively) [19]. Furthermore, NBIF showed the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonist activity [20]. However, the cytochromes P450 (CYP) and UGT metabolizing enzymes actively involved in metabolizing NBIF remain unknown.

Therefore, we investigated the metabolic pathways of NBIF in the present study to identify the corresponding main CYP and UGT enzymes and characterize species differences by HLM and animal liver microsomes. Metabolic rates were determined by incubating NBIF with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)− and uridine diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDPGA)-supplemented microsomes. Kinetic parameters were derived by fitting an appropriate model to the data. A series of independent assays including reaction phenotyping and activity correlation analysis were performed by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS) to identify the main CYPs and UGTs contributing to the metabolism of NBIF. Our results would improve the understanding of the metabolic fates of NBIF.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Neobavaisoflavone (purity > 98%) was purchased from Shanghai Winherb Medical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Alamethicin, D-saccharic-1, 4-lactone, MgCl2, NADPH, and UDPGA were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Human liver microsomes (HLM) and human intestine microsomes (HIM) were pooled from 20 and 50 mixed gender donors, respectively, and were both purchased form Corning Biosciences (Corning, NY, USA). Dogs liver microsomes (DLM), expressed human CYP enzymes (CYP1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4, and 3A5), individual pooled human liver microsomes (iHLM), mice liver microsomes (MLM), monkeys liver microsomes (MkLM), rabbits liver microsomes (RaLM), rats liver microsomes (RLM), and recombinant UGT enzymes (UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9, 1A10, 2B4, 2B7, 2B10, 2B15, and 2B17) were obtained from Corning Biosciences. Phenacetin, paracetamol, paclitaxel, 6α-hydroxy-paclitaxel, β-estradiol, and propofol and were purchased from Aladdin Chemicals (Shanghai, China). Propofol-O-glucuronide and β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade or the highest grade commercially available.

2.2. In vitro metabolism assay

In this study, the incubation system (100 μL) for phase I metabolism contained Tris-HCl buffer solution (50 mM, pH 7.4), drug-metabolizing enzyme solutions (0.5 mg/mL), MgCl2 (5 mM), a series of NBIF solutions (0.16–80 μM), and NADPH solution (1 mM) as described previously [21]. The reactions were terminated by adding cold acetonitrile (100 μL) after incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Furthermore, after centrifugation at 13,800 × g for 10 min, the supernatant (8 μL) was injected into an UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS system. A sample incubated without NADPH served as the negative control to confirm that the metabolites produced were NADPH-dependent. Similarly, NBIF was incubated with HIM, 12 iHLM samples, animal liver microsomes, and recombinant CYP enzymes in the incubation system. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

For glucuronidation assays, a series of NBIF solutions (0.16–80 μM) was incubated in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4), MgCl2 (4.0 mM), alamethicin (22 μg/mL), saccharolactone (4.4mM), and UDPGA solutions (3.5 mM) [21]. After 1 h, equal volumes of ice-cold acetonitrile (100 μL) were added to the incubation mixture to terminate the reactions. Additionally, the supernatant (8 μL) was subjected to UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS analysis after centrifugation at 13,800 × g for 10 min. Incubation without UDPGA served as the negative control to confirm that the metabolites produced were UDPGA-dependent. Similarly, the incubation system for HIM, 12 iHLM samples, animal liver microsomes, and each expressed CYP enzyme was similar to the microsomal incubation system described above. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3. UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS analysis

UHPLC analysis was performed on an Acquity™ UHPLC I-Class system equipped with PDA detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed on a BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, Part No. 186002350) maintained at 35 °C and with water (A) and acetonitrile (B) (both containing 0.1% formic acid, V/V) as the mobile phase. For phase I metabolism, the gradient elution program was 10–50% B from 0 to 2.0 min, 50–100% B from 2.0 to 3.0 min, maintained at 100% B from 3.0 to 3.2 min, 100–10% B from 3.2 to 3.5 min, and maintained at 10% B from 3.5 to 4.0 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. For glucuronidation assays, the gradient elution program was 10–30% B from 0 to 2.0 min, 30–33% B from 2.0 to 4.0 min, 33–90% B from 4.0 to 4.7 min, 90–100% B from 4.7 to 4.8 min, maintained at 100% B from 4.8 to 5.0 min, 100–10% B from 5.0 to 5.2 min, and maintained at 10% from 5.2 to 5.5 min at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The detection wavelength was 254 nm.

The UHPLC system was coupled to a hybrid quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight (Q-TOF) tandem mass spectrometer (SYNAPT™ G2 HDMS; Waters) equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI). The operating parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 3 kV (ESI+); sample cone voltage, 35 V; extraction cone voltage, 4 V; source temperature, 100 °C; desolvation temperature, 300 °C; cone gas flow, 50 L/h and desolvation gas flow, 800 L/h. The full scan mass range was 50–1500 Da. Leucine enkephalin was dissolved in acetonitrile-water (50:50, v/v, containing 0.1% formic acid) at 200pg/mL (m/z 556.2771 in positive ion mode), and was used as an external reference of LockSpray™ infused at a constant flow of 5 μL/min to ensure mass accuracy.

2.4. Enzyme kinetics evaluation

A series of NBIF concentrations (0.16–80 μM) was incubated with pooled HLM, HIM, each iHLM, expressed CYP enzymes, and recombinant UGT enzymes to determine the metabolic rates. Two kinetic models, the Michaelis-Menten equation and substrate inhibition equation, were fitted to the data of metabolic activities versus substrate concentrations and displayed in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. Appropriate models were selected by visual inspection of the Eadie-Hofstee plot [21]. Model fitting and parameter estimation were performed using GraphPad Prism V5 software (GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

The corresponding kinetic parameters were as follows. V is the formation rate of NBIF-related metabolites, Vmax is the maximal velocity. Km is the Michaelis constant, [S] is the substrate concentration, and Ksi is the substrate inhibition constant. The intrinsic clearance (CLint) values were derived from Vmax/Km for Michaelis-Menten and substrate inhibition models [21].

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.5. Activity correlation analysis

According to a previously described protocol, the metabolic rates of NBIF, phenacetin (probe substrate for CYP1A2) [21], paclitaxel (selective substrate for CYP2C8) [22], β-estradiol (probe substrate for UGT1A1) [23], and propofol (specific substrate for UGT1A9) [23] were determined for individual HLMs (n = 9). NBIF (5 μM), phenacetin (200 μM), and paclitaxel (20 μM) were incubated with NADPH-supplemented individual HLMs (n = 9), while NBIF (5 μM), β-estradiol (50 μM), and propofol (500 μM) were incubated with UDPGA-supplemented individual HLMs (n = 9). Furthermore, correlation analysis was performed between NBIF-oxidation (M1–M5) and phenacetin-N-deacetylation (paracetamol) and paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation (6α-hydroxy-paclitaxel), respectively. Correlation analysis was performed between NBIF-glucuronidation (G1 and G2) and β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation (β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide) and propofol-O-glucuronidation (propofol-O-glucuronide), respectively. These correlation (Pearson) analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism V5 software.

2.6. Species difference analysis

In this study, a series of NBIF solutions (0.16–80 μM) was incubated with five animal liver microsomes to determine the oxidation (M1–M5) and glucuronidation (G1 and G2) rates, respectively. Kinetic parameters were derived from the appropriate model fitting. Additionally, the CLint values for NBIF oxidation and glucuronidation by HLM and different animal liver microsomes were used as the evaluation parameters to estimate species diversity as published previously [21,23].

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are displayed as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Mean differences between the treatment and control groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test. The level of significance was set to p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***).

3. Results

3.1. Structural elucidation of NBIF-related metabolites by CYP and UGT enzymes

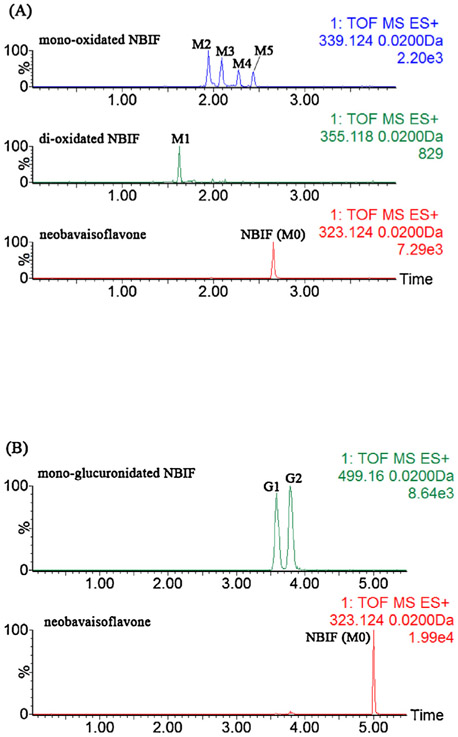

After incubation with NBIF by NADPH-supplemented HLM, five additional obvious peaks were detected by UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS with extracted ion chromatograms as shown in Fig. 1A. M0 was unambiguously identified as NBIF based on the reference standard. The mother ion at m/z 323.1286 (C20H19O4, 0.9 ppm, Fig. S1a) showed daughter ions at 267.066, 255.065, 239.075, and 137.023, which agreed with the results of our previous study [11 ]. Additionally, we characterized the oxidation sites of NBIF according to the presence or absence of the diagnostic ion at m/z 137.023 [11]. When a fragment ion was observed at m/z 137.023, the oxidation substituent was linked at the isopentenyl group of NBIF, whereas the oxidation position was at the A ring of NBIF when the characteristic ion at m/z 137.023 was absent [11]. Therefore, M1 (C20H19O6, −0.8 ppm, Fig. S1b) was characterized as di-oxidated NBIF with two oxidation units at the isopentenyl group of NBIF. Similarly, M2 (C20H19O5, 1.8 ppm, Fig. S1c) and M3 (C20H19O5, −2.1 ppm, Fig. S1d) were both considered as mono-oxidated NBIFs with the oxidation position at the isopentenyl unit, while the oxidation units of M4 (C20H19O5, −1.5 ppm, Fig. S1e) and M5 (C20H19O5, −2.9 ppm, Fig. S1f) were both on the A ring of NBIF.

Fig. 1.

Extracted ion chromatograms of NBIF, di-oxidated NBIF, mono-oxidated NBIF after incubation of NBIF with NADPH-supplemented HLM (A), and mono-glucuronidated NBIF after incubation of NBIF with UDPGA-supplemented HLM (B).

In contrast, when NBIF was incubated with UDPGA-supplemented HLM, two metabolites were detected by UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS (Fig. 1B). G1 (C26H27O10, 1.4 ppm, Fig. S1g) and G2 (C26H27O10, −0.8 ppm, Fig. S1h) both displayed the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 499.1611 which were 176.0321 Da higher than NBIF (M0) and similar to that of NBIF. Additionally, the fragment ion at m/z 113.026 suggested that G1 and G2 were mono-glucuronidated NBIF. According to the ClogP values [11], G1 (CLogP = 1.841) and G2 (CLogP = 2.084) were considered as NBIF-7-O-glucuronide and NBIF-4′-O-glucuronide, respectively. The UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS data for NBIF and its related metabolites are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS data of NBIF and its related metabolites.

| NO. | RT (min) | [M+H]+ ion | Formula | Error (ppm) | (+) ESI-MS/MS | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 2.65 | 323.1286 | C20H18O4 | 0.9 | 267.066 255.065 239.075 137.023 | NBIF |

| M1 | 1.55 | 355.1179 | C20H18O6 | −0.8 | 279.063 137.024 | di-oxidated-NBIF |

| M2 | 1.89 | 339.1238 | C20H18O5 | 1.8 | 321.113 279.066 137.024 | mono-oxidated-NBIF |

| M3 | 2.07 | 339.1225 | C20H18O5 | −2.1 | 321.113 279.067 137.025 | mono-oxidated-NBIF |

| M4 | 2.24 | 339.1227 | C20H18O5 | −1.5 | 283.060 271.060 255.064 181.069 | mono-oxidated-NBIF |

| M5 | 2.36 | 339.1222 | C20H18O5 | −2.9 | 283.062 271.061 255.065 181.070 | mono-oxidated-NBIF |

| G1 | 2.70 | 499.1611 | C26H26O10 | 1.4 | 323.131 267.065 255.066 113.026 | mono-glucuronidated-NBIF |

| G2 | 2.83 | 499.1600 | C26H26O10 | −0.8 | 323.131 267.065 255.066 113.026 | mono-glucuronidated-NBIF |

Note: NBIF, neobavaisoflavone.

3.2. Semi-quantification of NBIF and NBIF-related metabolites

Because of the lack of reference standards, semi-quantification of NBIF-related metabolites was based on the standard curve of NBIF according to the assumption that NBIF and its metabolites have similar UV absorbance maxima [21,23]. Thus, a practical UHPLC method was developed and validated for the semi-quantification of NBIF and its related metabolites. The limit of detection and limit of quantification were 0.005 and 0.01 μM, respectively. Additionally, an acceptable linear correlation (Y = 15392X) was confirmed by the correlation coefficient (r2) of 0.9994 between 0.01 and 20 μM.

3.3. Phase I metabolism and glucuronidation of NBIF in HLM and HIM

Kinetic profiling indicated that the mono-oxidation activities of NBIF (M2, M3, M4, and M5) in HLM followed classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics as shown in Fig. S2a and b. The intrinsic clearance (CLint) values of M2, M3, M4, and M5 were 12.43, 10.04, 2.01, and 6.99 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 2). Because the concentration was under the limit of quantification, we could not determine the kinetic parameters of M1 in HLM. Additionally, the phase I metabolism of NBIF in HIM was clearly weaker than that in HLM. Only M3 was detected after incubation with NBIF in HIM. Similarly, we could not obtain the complete kinetic profile of M3 in HIM.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters derived for NBIF-related oxidated metabolites (M1~M5) by HLM, HIM, expressed CYP enzymes, MkLM, RLM, MLM, DLM and RaLM (mean±SD). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

| Meta. |

Vmax (pmol/min/mg) |

Km (μM) |

Ki (μM) |

CLint (μL/min/mg) |

Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLM | M1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| M2 | 67.28 ± 3.68 | 5.41 ± 0.91 | N.A. | 12.43 ± 2.19 | MM | |

| M3 | 33.60 ± 1.39 | 3.35 ± 0.48 | N.A. | 10.04 ± 1.49 | MM | |

| M4 | 9.31 ± 0.40 | 4.64 ± 0.64 | N.A. | 2.01 ± 0.29 | MM | |

| M5 | 15.53 ± 0.30 | 2.22 ± 0.16 | N.A. | 6.99 ± 0.53 | MM | |

| HIM | M3 | + | + | + | + | |

| CYP1A1 | M1 | 30.63 ± 1.10 | 5.98 ± 0.78 | N.A. | 5.12 ± 0.67 | MM |

| M2 | 22.12 ± 3.13 | 2.62 ± 0.73 | 30.85 ± 10.56 | 8.43 ± 2.62 | SI | |

| M3 | 32.29 ± 2.38 | 1.06 ± 0.20 | 38.0 ± 8.78 | 30.46 ± 6.09 | SI | |

| M4 | 130.0 ± 32.38 | 3.72 ± 1.53 | 14.23 ± 6.25 | 34.96 ± 16.84 | SI | |

| M5 | 26.1 ± 2.33 | 1.38 ± 0.29 | 26.54 ± 5.97 | 18.89 ± 4.29 | SI | |

| CYP1A2 | M2 | 36.27 ± 1.07 | 23.73 ± 1.72 | N.A. | 1.53 ± 0.12 | MM |

| M3 | 601.9 ± 20.48 | 20.44 ± 1.78 | N.A. | 29.45 ± 2.75 | MM | |

| M4 | 266.6 ± 9.92 | 34.94 ± 2.81 | N.A. | 7.63 ± 0.68 | MM | |

| M5 | 36.83 ± 1.63 | 24.02 ± 2.60 | N.A. | 1.53 ± 0.18 | MM | |

| CYP1B1 | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M2 | + | + | + | + | ||

| M3 | + | + | + | + | ||

| M4 | + | + | + | + | ||

| CYP2A6 | M3 | + | + | + | + | |

| CYP2B6 | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M3 | + | + | + | + | ||

| CYP2C8 | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M2 | + | + | + | + | ||

| M3 | 121.8 ± 2.51 | 9.25 ± 0.61 | N.A. | 13.16 ± 0.90 | MM | |

| M4 | + | + | + | + | ||

| M5 | + | + | + | + | ||

| CYP2C9 | M3 | + | + | + | + | |

| M4 | + | + | + | + | ||

| CYP2C19 | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M2 | 912.0 ± 276.0 | 14.38 ± 5.79 | 15.94 ± 7.30 | 63.42 ± 31.94 | SI | |

| M3 | 197.5 ± 33.18 | 12.63 ± 2.82 | 12.77 ± 3.133 | 15.64 ± 4.37 | SI | |

| M4 | 52.38 ± 20.68 | 39.66 ± 19.72 | 24.84 ± 13.56 | 1.32 ± 0.84 | SI | |

| M5 | + | + | + | + | ||

| CYP2D6 | M3 | + | + | + | + | |

| M4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

| M5 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

| CYP2E1 | M3 | + | + | + | + | |

| CYP3A5 | M3 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| MkLM | M1 | + | + | + | + | + |

| M2 | 84.31 ± 1.83 | 2.81 ± 0.22 | N.A. | 29.99 ± 2.41 | MM | |

| M3 | 32.01 ± 1.19 | 2.29 ± 0.23 | 138.6 ± 21.68 | 13.98 ± 1.47 | SI | |

| M4 | 72.37 ± 1.75 | 2.24 ± 0.20 | N.A. | 32.38 ± 3.03 | MM | |

| M5 | 38.28 ± 5.80 | 12.22 ± 3.12 | 86.0 ± 31.3 | 3.13 ± 0.93 | SI | |

| RLM | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M2 | 100.5 ± 2.36 | 1.43 ± 0.14 | N.A. | 70.28 ± 6.93 | MM | |

| M3 | 134.0 ± 5.23 | 2.66 ± 0.22 | 57.83 ± 7.34 | 50.41 ± 4.55 | SI | |

| M4 | 295.9 ± 7.60 | 15.51 ± 1.10 | N.A. | 19.08 ± 1.44 | MM | |

| MLM | M1 | + | + | + | + | |

| M2 | 34.93 ± 1.01 | 3.42 ± 0.39 | N.A. | 10.23 ± 1.21 | MM | |

| M3 | 248.2 ± 7.12 | 22.75 ± 1.62 | N.A. | 10.91 ± 0.84 | MM | |

| DLM | M3 | 141.3 ± 9.61 | 21.0 ± 3.63 | N.A. | 6.73 ± 1.25 | MM |

| M4 | 15.71 ± 0.51 | 2.17 ± 0.31 | N.A. | 7.25 ± 1.07 | MM | |

| RaLM | M2 | 50.27 ± 2.31 | 3.47 ± 0.39 | 168.6 ± 33.94 | 14.49 ± 1.74 | SI |

| M3 | 311.5 ± 7.64 | 20.87 ± 1.30 | N.A. | 14.93 ± 1.00 | MM | |

| M4 | 27.95 ± 0.51 | 1.22 ± 0.11 | N.A. | 22.83 ± 2.13 | MM |

Note: Meta., metabolites; N.A., not available; +, under the limit of quantification; ++, unable to determine the kinetic parameters in the absence of a full kinetic profile; HLM, human liver microsomes; HIM, human intestine microsomes; MkLM, monkeys liver microsomes; RLM, rats liver microsomes; MLM, mice liver microsomes; DLM, dogs liver microsomes; RaLM, rabbits liver microsomes; SI, substrate inhibition model; MM, Michaelis-Menten model.

Compared to phase I metabolism, glucuronidation of NBIF was more efficient in both HLM and HIM. The formation of G1 in HLM was well-modeled by the substrate inhibition equation (Fig. S2c), while G2 followed the classical Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. S2c). In contrast, the metabolic rates of G1 and G2 in HIM followed the Michaelis-Menten kinetic and substrate inhibition equation, respectively (Fig. S2d). Additionally, the CLint values of G1 and G2 in HLM were 271.90 and 651.38 μL/min/mg (Table 3), respectively, whereas their corresponding parameters of G1 and G2 were 59.96 and 949.01 μL/min/mg in HIM, respectively (Table 3). The glucuronidation activities of NBIF far outweighed NBIF-related phase I metabolism.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters derived for NBIF-related glucuronides (G1 and G2) by HLM, HIM, expressed UGT enzymes, MkLM, RLM, MLM, DLM and RaLM (mean ± SD). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

| Enzyme | Meta. | Vmax (pmol/min/mg) | Km (μM) | Ki (μM) | CLint (μL/min/mg) | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLM | G1 | 1788.0 ± 203.6 | 6.58 ± 1.25 | 48.45 ± 13.86 | 271.90 ± 60.39 | SI |

| G2 | 919.1 ± 20.23 | 1.41 ± 0.13 | N.A. | 651.38 ± 60.31 | MM | |

| HIM | G1 | 409.3 ± 18.9 | 6.83 ± 0.91 | N.A. | 59.96 ± 8.42 | MM |

| G2 | 8655.0 ± 1021.0 | 9.12 ± 1.64 | 33.32 ± 7.95 | 949.01 ± 203.75 | SI | |

| UGT1A1 | G1 | 912.4 ± 49.36 | 3.64 ± 0.48 | 291.1 ± 100.1 | 250.87 ± 35.80 | SI |

| G2 | 48.33 ± 1.59 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 401.2 ± 135.7 | 47.01 ± 5.35 | SI | |

| UGT1A7 | G1 | 11.93 ± 0.55 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 61.82 ± 13.5 | 28.87 ± 4.57 | SI |

| G2 | 135.3 ± 4.36 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 154.5 ± 44.85 | 438.15 ± 56.41 | SI | |

| UGT1A8 | G1 | 419.1 ± 18.69 | 4.52 ± 0.54 | N.A. | 92.68 ± 11.73 | MM |

| G2 | 147.0 ± 6.84 | 4.0 ± 0.51 | N.A. | 36.75 ± 5.00 | MM | |

| UGT1A9 | G1 | 70.01 ± 1.37 | 1.77 ± 0.14 | N.A. | 39.49 ± 3.11 | MM |

| G2 | 805.9 ± 17.46 | 0.75 ± 0.07 | N.A. | 1073.25 ± 108.93 | MM | |

| UGT2B4 | G2 | + | + | + | + | |

| MkLM | G1 | 4129.0 ± 182.8 | 11.39 ± 1.25 | N.A. | 362.51 ± 42.87 | MM |

| G2 | 7072.0 ± 228.4 | 5.62 ± 0.55 | N.A. | 1257.92 ± 129.47 | MM | |

| RLM | G1 | 2490.0 ± 249.5 | 6.40 ± 1.01 | 24.73 ± 4.75 | 388.88 ± 72.83 | SI |

| G2 | 826.6 ± 99.48 | 2.95 ± 0.57 | 9.09 ± 1.82 | 280.11 ± 63.39 | SI | |

| MLM | G1 | 3589.0 ± 432.9 | 7.41 ± 1.43 | 38.19 ± 10.18 | 484.67 ± 110.41 | SI |

| G2 | 3878.0 ± 563.1 | 8.84 ± 1.96 | 31.68 ± 9.16 | 438.64 ± 116.08 | SI | |

| DLM | G1 | 1807.0 ± 48.14 | 9.31 ± 0.65 | N.A. | 194.09 ± 14.55 | MM |

| G2 | 3363.0 ± 85.47 | 3.48 ± 0.30 | N.A. | 965.27 ± 86.90 | MM | |

| RaLM | G1 | 3006.0 ± 103.8 | 4.82 ± 0.43 | N.A. | 623.26 ± 60.06 | MM |

| G2 | 3411.0 ± 155.5 | 4.13 ± 0.51 | N.A. | 826.61 ± 109.47 | MM |

Note: Meta., metabolites; N.A., not available; +, under the limit of quantification; HLM, human liver microsomes; HIM, human intestine microsomes; MkLM, monkeys liver microsomes; RLM, rats liver microsomes; DLM, dogs liver microsomes; MLM, mice liver microsomes; RaLM, rabbits liver microsomes; SI, substrate inhibition model; MM, Michaelis-Menten model.

3.4. Reaction phenotyping by CYP and UGT enzymes

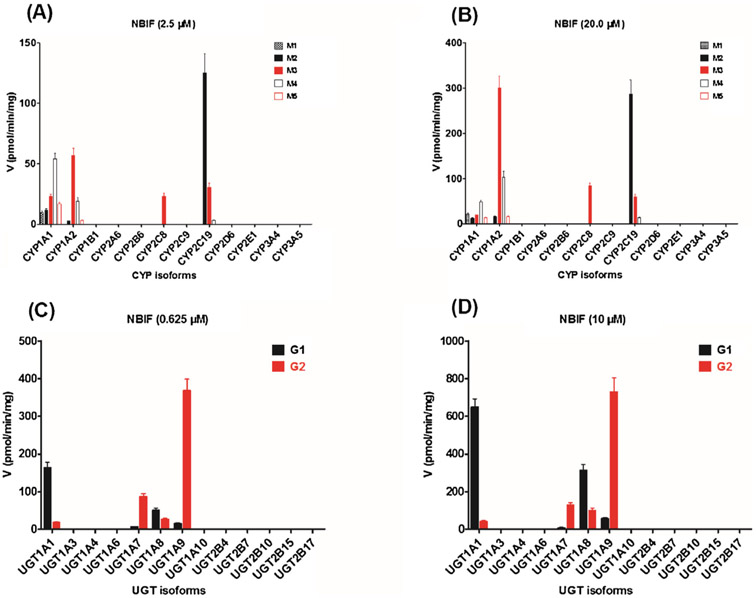

To determine which enzymes have the greatest contribution to phase I metabolism and glucuronidation, two test concentrations of NBIF were incubated with a series of expressed CYPs and UGTs enzymes to examine their catalysis activities (expressed as pmol/min/mg protein). The formation of M1 was mainly attributed to CYP1A1 (Fig. 2A and B), while M3 was produced by CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 (Fig. 2A and B). NBIF was catalyzed by CYP1A1, 1A2, and 2C19 to form M2 and M4 (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, M5 was mainly formed by CYP1A1 and 1A2 (Fig. 2A and B). Moreover, CYP1B1, 2A6, 2B6, 2C9, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A5 contributed to the formation of these five oxidated products of NBIF (Table 2). However, because the concentration of NBIF-related metabolites was lesser than the limit of quantification, we were unable to determine the complete kinetic parameters of these CYP enzymes.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of phase I metabolism rates (A: 2.5 μM; B: 20 μM) and glucuronidation rates (C: 0.625 μM; D: 10 μM) of NBIF by expressed CYP and UGT enzymes. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

As shown in Fig. 2C and D, the formation of G1 and G2 mainly contributed to expression of the UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 enzymes. UGT2B4 also catalyzed the production of G2 (Table 3) but the concentration was under the limit of quantification. Furthermore, other test UGT enzymes could not produce G1 and G2.

3.5. Phase I metabolism and glucuronidation kinetics by active CYP and UGT enzymes

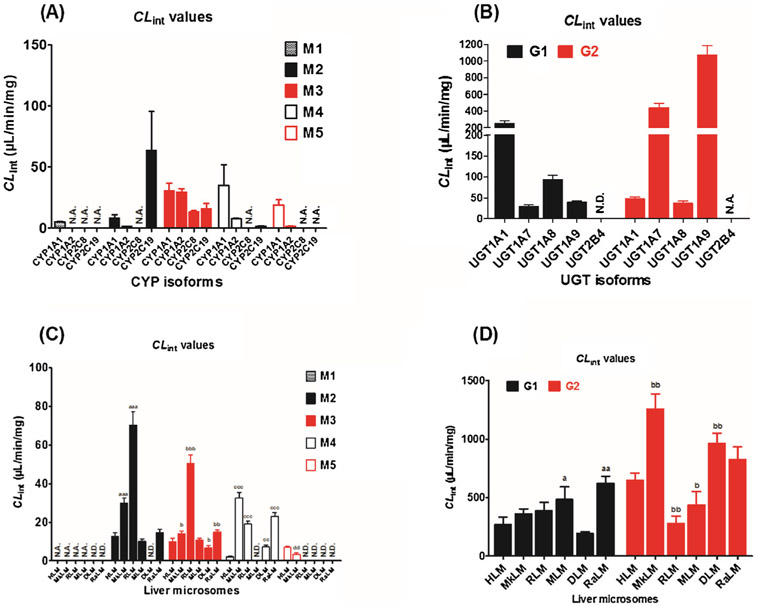

According to the reaction phenotyping results, CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 were the main active CYP enzymes involved in the phase I metabolism of NBIF (Fig. 2A and B). The formation of M1 by CYP1A1 followed classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. S3a), whereas the metabolic rates of M2, M3, M4, and M5 were all modeled by the substrate inhibition equation (Fig. S3b and c), which did not always follow the same kinetics as in HLM. The corresponding CLint values were 5.12, 8.43, 30.46, 34.96, and 18.89 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 2). Additionally, CYP1A2 catalyzed the formation of M2, M3, M4, and M5 following Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. S3d and e) with CLint values of 1.53, 29.45, 7.63, and 1.53 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 2), which agreed with the glucuronidation profiles in HLM. Notably, M3 was formed by CYP2C8 following Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. S3f), while the relative CLint value was 13.16 μL/min/mg (Table 2). Furthermore, the formation of M2, M3, and M4 all followed the substrate inhibition equation (Fig. S3g and h) with CLint values of 63.42, 15.64, and 1.32 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 2). Notably, M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5 were mainly formed by CYP1A1 (5.12 μL/min/mg), 2C19 (63.42 μL/min/mg), 1A1 (30.46 μL/min/mg), 1A1 (34.96 μL/min/mg), and 1A1 (18.89 μL/min/mg), respectively (Fig. 3A). Therefore, CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 were the main contributors to NBIF oxidation.

Fig. 3.

Intrinsic clearance (CLint) values of NBIF-related metabolites by expressed CYPs (A), recombinant UGTs (B), HLM and five animal liver microsomes for phase I metabolism (C) and glucuronidation (D). N.D., not detected. N.A., under the limit of quantification or unable to determine the kinetic parameters in the absence of a full kinetic profile. a, b, c, d compared with the CLint values of NBIF-related metabolites in HLM, respectively. (a, b, c, d p < 0.05, aa, bb, cc, dd p < 0.01, aaa, bbb, ccc, ddd p < 0.001).

As clearly shown in Fig. 2C and D, UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 were active contributors to the glucuronidation of NBIF. Glucuronidation reactions (250.87 μL/min/mg for G1 and 47.01 μL/min/mg for G2) mediated by UGT1A1 both followed substrate inhibition kinetics (Fig. 4a), which agreed with the glucuronidation profiles (G1) in HLM (Fig. S2c). Similarly, the production of G1 and G2 by UGT1A7 followed the substrate inhibition equation (Fig. 4b) with CLint values of 28.87 and 438.15 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 3). Additionally, glucuronidation of NBIF by UGT1A8 and 1A9 all were modeled by classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 4c and d). The CLint values for G1 and G2 by UGT1A8 were 92.68 and 36.75 μL/min/mg (Table 3), respectively, and the CLint values of 39.49 and 1073.25 μL/min/mg (Table 3) by UGT1A9, respectively. In general, UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 were mainly responsible for the glucuronidation of NBIF (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

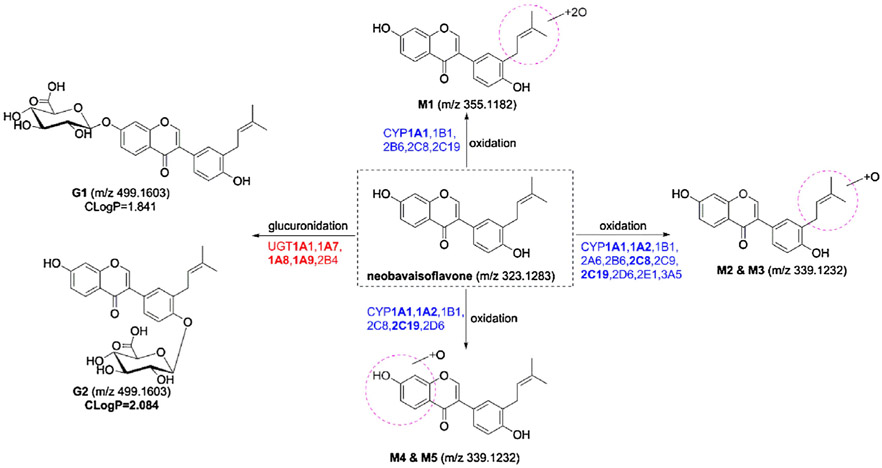

Metabolic pathways of NBIF involving in CYPs and UGTs.

3.6. Activity correlation analysis by active CYP and UGT enzymes

The phase I metabolism and glucuronidation activities of individual HLMs (n = 9) toward NBIF and probe substrates of CYP1A2, 2C8 [21,22] and UGT1A1, 1A9 [23] were evaluated. We found that phenacetin-N-deacetylation was strongly correlated with M3 (r = 0.860, p = 0.003, Fig. S5b) and M4 (r = 0.775, p = 0.014, Fig. S5c), indicating that CYP1A2 plays a critical role in the formation of M3 and M4. In contrast, there were no significant differences between phenacetin-N-deacetylation and M2 (r = 0.525, p = 0.147, Fig. S5a), M5 (r = 0.382, p = 0.310, Fig. S5d). Additionally, significant activity correlation was observed between paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation and M2 (r = 0.675, p = 0.046, Fig. S6a) and M3 (r = 0.829, p = 0.006, Fig. S6b), while no obvious differences (p > 0.05) were detected between paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation and M4 (r = 0.577, p = 0.104, Fig. S6c) and M5 (r = 0.284, p = 0.460, Fig. S6d). The detailed correlation factors are shown in Table 4. These finding suggest that CYP1A2 is the greatest contributor to M3 and M4 production, whereas CYP2C8 plays an important role in M2 and M3 formation.

Table 4.

Metabolic activities correlation analysis of individual HLMs (n = 9) toward NBIF, phenacetin, paclitaxel, β-estradiol and propofol.

| Enzyme | Probe substrate | Metabolite | r value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | phenacetin-N-deacetylation | NBIF-oxidation (M2) | 0.525 | 0.147 |

| CYP1A2 | phenacetin-N-deacetylation | NBIF-oxidation (M3) | 0.860 | 0.003, ** |

| CYP1A2 | phenacetin-N-deacetylation | NBIF-oxidation (M4) | 0.775 | 0.014, * |

| CYP1A2 | phenacetin-N-deacetylation | NBIF-oxidation (M5) | 0.382 | 0.310 |

| CYP2C8 | paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation | NBIF-oxidation (M2) | 0.675 | 0.046, * |

| CYP2C8 | paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation | NBIF-oxidation (M3) | 0.829 | 0.006, ** |

| CYP2C8 | paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation | NBIF-oxidation (M4) | 0.577 | 0.104 |

| CYP2C8 | paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation | NBIF-oxidation (M5) | 0.284 | 0.460 |

| UGT1A1 | β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation | NBIF-O-glucuronidation (G1) | 0.822 | 0.007, ** |

| UGT1A1 | β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation | NBIF-O-glucuronidation (G2) | 0.689 | 0.040, * |

| UGT1A9 | propofol-O-glucuronidation | NBIF-O-glucuronidation (G1) | 0.768 | 0.016, * |

| UGT1A9 | propofol-O-glucuronidation | NBIF-O-glucuronidation (G2) | 0.860 | 0.003, ** |

Note: NBIF, neobavaisoflavone. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Notably, there was strong correlation between β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide and G1 (r = 0.822, p = 0.007, Fig. S7a) and G2 (r = 0.689, p = 0.040, Fig. S7b) in the bank of individual HLMs (n = 9), respectively. The formation of G1 (r = 0.768, p = 0.016, Fig. S7c) and G2 (r = 0.860, p = 0.003, Fig. S7d) was also significantly correlated with propofol-O-glucuronidation. These results indicate that UGT1A1 and 1A9 catalyzed massive glucuronidation to form G1 and G2, respectively.

3.7. Species differences

As shown in Fig. 3C, M2, M3, and M4 were the main metabolites of NBIF produced by animal liver microsomes. The kinetic profiles of M2 and M4 in MkLM (Fig. S8a), M2 and M4 in RLM (Fig. S8c and d), M2 and M3 in MLM (Fig. S8e), M3 and M4 in DLM (Fig. S8f), and M3 and M4 in RaLM (Fig. S8g and h) followed the classical Michaelis-Menten equation, while M3 in MkLM (Fig. S8b), M3 in RLM (Fig. S8c), and M2 in RaLM (Fig. S8g) were modeled to the substrate inhibition equation. The catalytic efficiencies (reflected by CLint values, Fig. 3C) for M2 by HLM and animal liver microsomes followed the order of RLM (70.28 μL/min/mg) > MkLM (29.99 μL/min/mg) > RaLM (14.49 μL/min/mg) > HLM (12.43 μL/min/mg) > MLM (10.23 μL/min/mg) (Table 2). Similarly, the CLint values of M3 in RLM, RaLM, MkLM, MLM, HLM, and DLM were 50.41, 14.93, 13.98, 10.91, 10.04, and 6.73 μL/min/mg, respectively (Table 2). Similarly, the CLint value order for M4 was MkLM (32.38 μL/min/mg) RaLM (22.83 μL/min/mg) > RLM (19.08 μL/min/mg) > DLM (7.25 μL/min/mg) > HLM (2.01 μL/min/mg) (Table 2).

As in the glucuronidation of NBIF in HLM, NBIF was rapidly metabolized into two glucuronides by animal liver microsomes (Fig. 3D). Additionally, the Michaelis-Menten equation fit best to the glucuronidation (G1 and G2) of NBIF by MkLM (Fig. S9a), DLM (Fig. S9d), and RaLM (Fig. S9e), whereas glucuronidation in RLM (Fig. S9b) and MLM (Fig. S9c) followed substrate inhibition kinetics. For G1, the CLint value order was RaLM (623.26 μL/min/mg) > MLM (484.67 μL/min/mg) > RLM (388.88 μL/min/mg) > MkLM (362.51 μL/min/mg) > HLM (271.90 μL/min/mg) > DLM (194.09 μL/min/mg) (Table 3). Similarly, the CLint values for G2 were 1257.92 μL/min/mg (MkLM), 965.27 μL/min/mg (DLM), 826.61 μL/min/mg (DLM), 651.38 μL/min/mg (HLM), 438.64 μL/min/mg (MLM), and 280.11 μL/min/mg (RLM) (Table 3).

Taken together, our results clearly revealed marked species differences in the phase I metabolism (approximately 16.1-fold) and glucuronidation (approximately 2.3-fold) of NBIF. Additionally, mice are the best model for NBIF-related oxidation and glucuronidation studies in humans because of their appropriate CLint values.

4. Discussion

NBIF, as a major bioactive compound in P. corylifolia, has gained increasing attentions in recent years [4-10]. NBIF undergoes massive phase I and II metabolism in vivo and in the intestinal microflora [11,12], explaining why the pharmacokinetic behaviors of NBIF have been characterized as rapid oral absorption, high clearance, and poor absolute bioavailability [13-15]. We further examined the phase I and glucuronidation pathways of NBIF in the human liver and intestine.

Our results indicated that NBIF could be rapidly oxidized and glucuronidated in both HLM and HIM (Fig. 1). Notably, the oxidation rates (CLint values less than 12.43 μL/min/mg) were clearly weaker than the glucuronidation rates (CLint values between 59.96 and 949.01 μL/min/mg) of NBIF in HLM (Table 2) and HIM (Table 3). These results agree with those of our previous study showing that glucuronidation was the major metabolic pathway of corylin in HLM and HIM [21]. Additionally, CYP1A1, 1A2, and 2C19 clearly exhibited significant catalytic activities toward the A ring of prenylflavonoid, while CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 showed strong oxidation activities towards the isopentene group of prenylflavonoid, which agrees with previous results for corylin [21]. CYP1A1 also played the most important role in the dioxidation activities of the isopentene group of NBIF. The oxidation activities toward the isopentene group by CYP enzymes were the major oxidation reaction of NBIF. In addition, NBIF, also known as an individual prenylflavonoid, was efficiently glucuronidated, in addition to wushanicaritin (CLint values >160 μL/min/mg) [23,24] and icaritin (CLint values more than 270 μL/min/mg) [25]. Therefore, the first-pass glucuronidation reaction played a vital role compared to phase I metabolism (mainly oxidation) for NBIF clearance and determining bioavailability.

Because NBIF-containing herbal preparations are widely used in clinics, it is important to clarify the metabolic clearance of NBIF involving CYPs and UGTs in human. In the present study, CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 (Fig. S3) and UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 (Fig. S4) mainly participated in the oxidation and glucuronidation of NBIF, while CYP2C19 and UGT1A9 displayed the best catalytic activity for NBIF-related mono-oxidation (CLint value = 63.42 μL/min/mg, Table 2) and glucuronidation (CLint value = 1073.25 μL/min/mg, Table 3). CYP1A1, UGT1A7, and 1A8 were absent from the human liver and were mainly expressed in the intestine, stomach, and kidney [26,27], while CYP1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 and UGT1A1, 1A9 were mainly expressed in the human liver [26,27]. These findings showed that NBIF-related metabolism in the human liver and intestine for determining its oral bioavailability should not be underestimated, particularly the glucuronidation reactions.

Activity correlation analysis and reaction phenotyping experiments are also important for determining the contribution of individual CYP or UGT enzymes to respective phase I and II metabolism [21,23,25]. As shown in Table 4, phenacetin-N-deacetylation (Fig. S5), paclitaxel-6-hydroxylation (Fig. S6), β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation (Fig. S7), and propofol-O-glucuronidation (Fig. S5) were all significantly correlated with the formation of NBIF-related metabolites in a bank of individual HLMs (n = 9). The reason we did not determine the roles of CYP1A1, UGT1A7, and 1A8 in hepatic metabolism of NBIF was that they were not detected in the human liver or are not widely accepted probe substrates, although they exhibited high metabolic activities towards NBIF. These results (Table 4) support that CYP1A2 and 2C8 and UGT1A1 and 1A9 play key roles in the hepatic metabolism of NBIF.

Notably, because of the presence of bovine serum albumin, uncorrected parameters may lead to erroneous estimation of in vivo metabolic activities, namely poor in vivo-in vitro extrapolation, significantly weakening the ability to predict pharmacokinetics properties [28]. Hence, it is important to identify the protein binding factors affecting the outcome of in vitro metabolism assays. The Hallifax and Houston model, a widely recognized prediction approach, provides accurate predictions of free unbound (fu) values based on the log P values of compounds with intermediate lipophilicity (log P values between 2.5 and 5.0) [29]. Therefore, binding between NBIF (log P = 3.73) and microsomal proteins may be negligible according to the Hallifax and Houston model, while the kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, CLint, etc.) did not require correction in this study.

Among the active individual enzymes (Fig. 3A and B), CYP1A2, 2C19, and UGT1A1 catalyzed approximately 9%, 12%, and 15% of marketed drugs, respectively [30], while these active isoforms also catalyzed the metabolism of endogenous agents [26]. For example, CYP1A1 is involved in the bioactivation of foreign agents [e.g., benzo(a)pyrene] to carcinogens and has been implicated in the formation of various types of human cancer [31]. Additionally, CYP1A1 and 1A2 metabolize polyunsaturated fatty acids into signaling molecules with physiological and pathological activities [32]. UGT1A1 also appeared to be of particular importance in maintaining human health because UGT1A1 is the sole physiologically relevant enzyme participating in the clearance of bilirubin, and plays a key role in the metabolism of many therapeutic drugs (e.g., irinotecan, morphine) [33]. The competition of these active CYP or UGT enzymes substrates [e.g., phenacetin, paclitaxel, (S)-mephenytoin, β-estradiol, bilirubin, propofol] may greatly decrease enzyme function and reduce the metabolism rate of NBIF in vivo. Common genetic polymorphisms among different ethnicities are important factors influencing the expression levels and activities of CYPs and UGTs. In clinics, before several therapeutic drugs (e.g., omeprazole, sertraline, clopidogrel, warfarin, voriconazole) are orally administered, the polymorphisms in CYP2C19 (CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, CYP2C19*17) must be analyzed using gene detection approaches [34]. Similarly, the expression of UGT1A1 polymorphisms (UGT1A1*6, UGT1A1*28) should be detected to avoid or reduce the dose-limiting toxicities in irinotecan chemotherapy [35]. Therefore, humans with CYP or UGT enzyme dysfunction or genetic polymorphisms likely exhibit altered metabolism of NBIF, which alters its bioavailability in vivo.

5. Conclusion

This is the first study to characterize NBIF-related oxidation and glucuronidation pathways in human (Fig. 4). CYP and UGT isoforms involved in NBIF-oxidation and NBIF-O-glucuronidation, and their respective catalytic activities, were expressed as CLint values by HLM, HIM, recombinant CYPs, and expressed UGTs (Tables 2 and 3). The results indicated that CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, 2C19, and UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, 1A9 were the main contributors to the phase I metabolism and glucuronidation of NBIF in HLM and HIM (Fig. 3A and B). Activity correlation analysis assays showed that the formation of several NBIF-related metabolites was significantly correlated with the probe substrates of active CYP or UGT enzyme-related metabolism in a bank of individual HLM (n = 9) (Table 4), suggesting that CYP1A2 and 2C8 and UGT1A1 and 1A9 play important roles in the hepatic metabolism of NBIF. Moreover, there were marked species differences in the oxidation and glucuronidation of NBIF between HLM and animal liver microsomes from monkeys, rats, mice, dogs, and rabbits (Fig. 3C and D), and mice may be the best animal model for evaluating the oxidation and glucuronidation of NBIF in humans. Taken altogether, NBIF underwent massive glucuronidation in both HLM and HIM compared to oxidation, indicating that CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 and UGT1A1, 1A7, 1A8, and 1A9 are the most active isoform enzymes. Thus, characterization of NBIF-related metabolic pathways involving the key CYP and UGT enzymes (Fig. 4) would reveal the pharmacokinetic behaviors and metabolic fates of NBIF in the human liver and intestine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

All the authors would like to thank Guangzhou Research and Creativity Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Guangzhou, China) for the samples tests. This work was also supported by Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B13038) of China, Major Project for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81220108028), State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81630097), Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Project (2016B090921005) and National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2017A03031387).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2018.06.022.

References

- [1].Chopra B, Dhingra AK, Dhar KL, Psoralea corylifolia L. (Buguchi)-folklore to modern evidence: review, Fitoterapia 90 (2013) 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yan C, Wu Y, Weng Z, Gao Q, Yang G, Chen Z, Cai B, Li W, Development of an HPLC method for absolute quantification and QAMS of flavonoids components in Psoralea corylifolia L, J. Anal. Methods Chem 2015 (2015) 792637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim YJ, Lim HS, Lee J, Jeong SJ, Quantitative analysis of psoralea corylifolia Linne and its neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory effects in HT22 hippocampal cells and BV-2 microglia, Molecules 21 (2016) 1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tsai WJ, Hsin WC, Chen CC, Antiplatelet flavonoids from seeds of Psoralea corylifolia, J. Nat. Prod 59 (1996) 671–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Szliszka E, Skaba D, Czuba ZP, Krol W, Inhibition of inflammatory mediators by neobavaisoflavone in activated RAW264.7 macrophages, Molecules 16 (2011) 3701–3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Szliszka E, Czuba ZP, Sędek Ł, Paradysz A, Król W, Enhanced TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by the bioactive compounds neobavaisoflavone and psoralidin isolated from Psoralea corylifolia, Pharmacol. Rep 63 (2011) 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xin D, Wang H, Yang J, Su YF, Fan GW, Wang YF, Zhu Y, Gao XM, Phytoestrogens from Psoralea corylifolia reveal estrogen receptor-subtype selectivity, Phytomedicine 17 (2010) 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Oh KY, Lee JH, Curtis-Long MJ, Cho JK, Kim JY, Lee WS, Park KH, Glycosidase inhibitory phenolic compounds from the seed of Psoralea corylifolia, Food Chem. 121 (2010) 940–945. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Don MJ, Lin LC, Chiou WF, Neobavaisoflavone stimulates osteogenesis via p38-mediated up-regulation of transcription factors and osteoid genes expression in MC3T3-E1 cells, Phytomedicine 19 (2012) 551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim YJ, Choi WI, Ko H, So Y, Kang KS, Kim I, Kim K, Yoon HG, Kim TJ, Choi KC, Neobavaisoflavone sensitizes apoptosis via the inhibition of metastasis in TRAIL-resistant human glioma U373MG cells, Life Sci. 95 (2014) 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang PL, Yao ZH, Zhang FX, Shen XY, Dai Y, Qin L, Yao XS, Identification of metabolites of PSORALEAE FRUCTUS in rats by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry analysis, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 112 (2015) 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gao MX, Tang XY, Zhang FX, Yao ZH, Yao XS, Dai Y, Biotransformation and metabolic profile of Xian-Ling-Gu-Bao capsule, a traditional Chinese medicine prescription, with rat intestinal microflora by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry analysis, Biomed. Chromatogr 32 (2018) e4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gao Q, Xu Z, Zhao G, Wang H, Weng Z, Pei K, Wu L, Cai B, Chen Z, Li W, Simultaneous quantification of5 main components of Psoralea corylifolia L. in rats’ plasma by utilizing ultra high pressure liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry J. Chromatogr. B 1011 (2016) 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yao ZH, Qin ZF, He LL, Wang XL, Dai Y, Qin L, Gonzalez FJ, Ye WC, Yao XS, Identification, bioactivity evaluation and pharmacokinetics of multiple components in rat serum after oral administration of Xian-Ling-Gu-Bao capsule by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry, J. Chromatogr. B 1041–1042 (2017) 104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yang YF, Zhang YB, Chen ZJ, Zhang YT, Yang XW, Plasma pharmacokinetics and cerebral nuclei distribution of major constituents of Psoraleae fructus in rats after oral administration, Phytomedicine 38 (2018) 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang XX, Lv X, Li SY, Hou J, Ning J, Wang JY, Cao YF, Ge GB, Guo B, Yang L, Identification and characterization of naturally occurring inhibitors against UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 in Fructus Psoraleae (Bu-gu-zhi), Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 289 (2015) 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sun DX, Ge GB, Dong PP, Cao YF, Fu ZW, Ran RX, Wu X, Zhang YY, Hua HM, Zhao Z, Fang ZZ, Inhibition behavior of fructus psoraleae’s ingredients towards human carboxylesterase 1 (hCES1, Xenobiotica 46 (2016) 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li YG, Hou J, Li SY, Lv X, Ning J, Wang P, Liu ZM, Ge GB, Ren JY, Yang L, Fructus Psoraleae contains natural compounds with potent inhibitory effects towards human carboxylesterase 2, Fitoterapia 101 (2015) 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zarmouh NO, Eyunni SK, Soliman KF, The benzopyrone biochanin-A as a reversible, competitive, and selective monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, BMC Complement. Altern. Med 17 (2017) 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ma S, Huang Y, Zhao Y Du G, Feng L, Huang C, Li Y, Guo F, Prenylflavone derivatives from the seeds of Psoralea corylifolia exhibited PPAR-γ agonist activity, Phytochem. Lett 16 (2016) 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Qin Z, Li S, Yao Z, Hong X, Xu J, Lin P, Zhao G, Gonzalez FJ, Yao X, Metabolic profiling of corylin in vivo and in vitro, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 155 (2018) 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ho MCD, Ring N, Amaral K, Doshi U, Li AP, Human enterocytes as an in vitro model for the evaluation of intestinal drug metabolism: characterization of drug-metabolizing enzyme activities of cryopreserved human enterocytes from twenty-four donors, Drug Metab. Dispos 45 (2017) 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hong X, Zheng Y, Qin Z, Wu B, Dai Y, Gao H, Yao Z, Gonzalez FJ, Yao X, In vitro glucuronidation of wushanicaritin by liver microsomes, intestine microsomes and expressed human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes, Int. J. Mol. Sci 18 (2017) 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qin Zifei, Li Shishi, Yao Zhihong, Hong Xiaodan, Wu Baojian, Krausz Kristopher W., Gonzalez Frank J., Gao Hao, Xinsheng Yao, Chemical inhibition and stable knock-down of efflux transporters leads to reduced glucuronidation of wushanicaritin in UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells: the role of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs) in the excretion of glucuronides, Food Funct. 9 (2018) 1410–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang L, Hong X, Yao Z, Dai Y, Zhao G, Qin Z, Wu B, Gonzalez FJ, Yao X, Glucuronidation of icaritin by human liver microsomes, human intestine microsomes and expressed UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes: identification of UGT1A3, 1A9 and 2B7 as the main contributing enzymes, Xenobiotica 48 (2018) 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Manikandan P, Nagini S, Cytochrome P450 structure, function and clinical significance: a review, Curr. Drug Targets 19 (2018) 38–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ohno S, Nakajin S, Determination of mRNA expression of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and application for localization in various human tissues by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, Drug Metab. Dispos 37 (2009) 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Manevski N, Moreolo PS, Yli-Kauhaluoma J, Finel M, Bovine serum albumin decreases Km values of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A9 and 2B7 and increases Vmax values of UGT1A9, Drug Metab. Dispos 39 (2011) 2117–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gao H, Steyn SJ, Chang G, Lin J, Assessment of in silico models for fraction of unbound drug in human liver microsomes, Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 6 (2010) 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Williams JA, Hyland R, Jones BC, Smith DA, Hurst S, Goosen TC, Peterkin V, Koup JR, Ball SE, Drug-drug interactions for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase substrates: a pharmacokinetic explanation for typically observed low exposure (AUCi/AUC) ratios, Drug Metab. Dispos 32 (2004) 1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Go RE, Hwang KA, Choi KC, Cytochrome P450 1 family and cancers, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 147 (2015) 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Westphal C, Konkel A, Schunck WH, CYP-eicosanoids–a new link between omega-3 fatty acids and cardiac disease? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 96 (2011) 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Iyer L, Hall D, Das S, Mortell MA, Ramírez J, Kim S, Di Rienzo A, Ratain MJ, Phenotype-genotype correlation of in vitro SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver tissue with UGT1A1 promoter polymorphism, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 65 (1999) 576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Desta Z, Zhao X, Shin J-G, Flockhart DA, Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism, Clin. Pharmacokinet 41 (2002) 913–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nagar S, Blanchard RL, Pharmacogenetics of uridine diphosphoglucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A family members and its role in patient response to irinotecan, Drug Metab. Rev 38 (2006) 393–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.