Abstract

The plant receptor-like-kinase subfamily CrRLK1L has been widely studied, and CrRLK1Ls have been described as crucial regulators in many processes in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.), Heynh. Little is known, however, about the functions of these proteins in other plant species, including potential roles in symbiotic nodulation. We performed a phylogenetic analysis of CrRLK1L subfamily receptors of 57 different plant species and identified 1050 CrRLK1L proteins, clustered into 11 clades. This analysis revealed that the CrRLK1L subfamily probably arose in plants during the transition from chlorophytes to embryophytes and has undergone several duplication events during its evolution. Among the CrRLK1Ls of legumes and A. thaliana, protein structure, gene structure, and expression patterns were highly conserved. Some legume CrRLK1L genes were active in nodules. A detailed analysis of eight nodule-expressed genes in Phaseolus vulgaris L. showed that these genes were differentially expressed in roots at different stages of the symbiotic process. These data suggest that CrRLK1Ls are both conserved and underwent diversification in a wide group of plants, and shed light on the roles of these genes in legume–rhizobia symbiosis.

Keywords: CrRLK1L, expression profile, legumes, nodule symbiosis, phylogenetic analysis

1. Introduction

Plants are continually exposed to many environmental conditions that they must contend with to survive. These conditions are perceived by plant cells as physical or chemical signals that are sensed by plasma membrane receptors. The receptor-like kinase (RLK) family is one of the largest receptor families and is represented in all organisms. RLKs are involved in many processes, including the perception of pathogens and symbiotic partners. Defense-associated RLKs are activated by pathogen-derived molecules (such as flagellin or fungal chitin) and initiate defense responses. Other specific RLKs bind to signal molecules from mycorrhizal fungi or rhizobia, triggering symbiosis.

In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (L.), Heynh, about 600 RLKs have been described, and they have been classified into several subfamilies [1]. The Catharanthus roseous (L.), D.Don RLK-1L (CrRLK1L) subfamily is unique to plants [2] and has been widely studied in A. thaliana. CrRLK1L receptors are characterized by a carbohydrate-binding domain known as the malectin-like domain for its similarity to the animal protein malectin [3]. The A. thaliana genome harbors 17 CrRLK1Ls [2], of which FERONIA (FER) has been the most studied. FER was initially characterized as a regulator of female fertility; later, it was described as an important regulator in some phytohormone signaling pathways [4,5,6,7,8,9] and was shown to be essential for polar growth in root hair cells (Table S1) [10]. More recently, FER has been reported to be a negative regulator of the immune response in plants [11,12], an activator of protein synthesis [13], and a regulator of growth in response to metabolic status (the C/N ratio) (Table 1) [14].

Table 1.

CrRLK1L genes studied in different plant species.

| Gene Name | Plant Species | Mutant/RNAi | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FERONIA | A. thaliana | fer | PT overgrowth, multiple PT reach one ovules | [15,16,17,18,19] |

| fer | Collapsed, burst and short RH | [10] | ||

| fer | Resistance to Powdery mildew infection, increased susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomaeum DC3000 | [11,20] | ||

| fer | Ethylene hypersensitivity, brassinosteroid insensitivity, abscisic acid hypersensitivity, an increase of s-adenosyl methionine synthesis, inhibition of jasmonic acid responses | [5,6,7,9] | ||

| FER RNAi | Dwarf phenotype | [4,21] | ||

| fer | Larger seed size | [22] | ||

| fer | Salt hypersensitivity | [23] | ||

| fer | Increased starch accumulation in a sucrose medium. Hypersensitivity to high carbon/nitrogen ratio | [14,24] | ||

| fer | Reduced induction of ErbB3-binding protein 1, alteration of ribosome synthesis | [13,25] | ||

| fer | Delay in the flowering time under long day condition | [26] | ||

| fer | Hypersensitivity to nickel, tolerance to cadmium, coper, zinc, and lead | [27] | ||

| Oriza sativa L. | flr2 | Enhanced resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae infection | [28] | |

| flr11 | Enhanced resistance to M. oryzae infection | [28] | ||

| Fragaria x ananassa | FaMRL47RNAi | Fruit ripening acceleration | [29] | |

| BUPS1/2 | A. thaliana | bups1 | PT overgrowth | [30] |

| bups1 bups2 | Enhanced bups1 phenotype: PT overgrowth | |||

| ANXUR1/2 | A. thaliana | anx1 anx2 | Reduced fertility, PT burst | [19,31,32] |

| HERKULES1 | A. thaliana | herk1 the | Dwarf plants | [19,27,33] |

| herk1 | Tolerance to cadmium, coper, nickel, and zinc | |||

| herk1 | PT overgrowth | |||

| HERKULES2 | A. thaliana | herk2 | Tolerance to cadmium, coper, nickel, and lead | [27] |

| ANJEA | A. thaliana | herk anj | PT overgrowth | [33] |

| THESEUS1 | A. thaliana | the prc | Rescues of hypocotyl growth but without prc cellulose deficiency phenotype | [34] |

| the | Hypersensitivity to lead and zinc, tolerance to nickel | [27] | ||

| herk1 the | Dwarf plants | [4] | ||

| CAP | A. thaliana | cap | Altered PT growth in low calcium | [35] |

| cap | RH bursting and bulging | [36] | ||

| CURVY | A. thaliana | crv | Distortion of trichomes, altered pavement morphology | [37] |

| MEDOS1-4 | A. thaliana | med1,2,3,4 | Reduced growth in presence of metal ions | [38] |

PT: pollen tubes, RH: root hairs, prc: A. thaliana mutant procuste.

In association with FER, other CrRLK1Ls, such as HERKULES1 (HERK1), HERK2, and THESEUS1 (THE1), are involved in cell wall maintenance and cytoplasmic membrane homeostasis (Table 1) [4]. During fertilization, two CrRLK1Ls, HERK1 and ANJEA, together with FER, mediate male–female gametophyte interaction at the synergid cells (Table 1) [33]. Four other CrRLK1Ls, ANXUR1 (ANX1), ANX2, BUDDHAs PAPER SEAL1 (BUPS1), and BUPS2 are essential for preserving the integrity of the pollen tube during growth (Table 1) [30,31]. The CrRLK1L CAP regulates calcium-dependent pollen tube growth, and is also implicated in maintaining cell wall composition in root hairs during tip growth (Table 1) [35,36]. CURVY1, another CrRLK1L, is important in trichome and tapetal cell morphogenesis, the vegetative-to-reproductive state transition, and seed production (Table 1) [37]. Four other CrRLK1Ls, MEDOS1-4, are associated with the regulation of plant development in response to the presence of metal ions (Table 1) [38].

RALF (Rapid alkalinization factor) peptides have been described as ligands of some of the CrRLK1L receptors [8,20,39,40]. These peptides are widely distributed in all land plants, and their activity is associated with pH modulation and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [39,41,42]. A. thaliana has 34 RALF peptides, which are differentially expressed in different plant tissues [43,44], and a total of 795 RALFs have been identified in 51 different plant species (monocots, eudicots, and early-diverging lineages) [44]. The cysteine-rich peptide RALF1 was the first peptide described as a FER ligand [39]. The RALF1-FER complex is important for fine-tuning the plant response to non-peptide hormones, root elongation, and polar root hair growth in A. thaliana [8]. RALF34, RALF4, and RALF19 interact with the CrRLK1L complex BUPS1/2-ANX1/2 during fertilization [40]. RALF34 also binds to THE1 in roots, a signaling step required for division of the pericycle during lateral root initiation [40]. RALF23 acts as a negative regulator of immunity through its interaction with FER [20]. In symbiotic interactions, it has been reported that the Medicago truncatula Gaertn. homolog of RALF1 (MtRALF1) functions as a negative regulator of nodule formation during the development of nitrogen-fixing symbioses; however, the receptor that recognizes MtRALF1 and triggers this inhibition of nodule formation is unknown [45].

The formation of nitrogen-fixing root nodules is a complex process and occurs almost exclusively in legumes, a large family of plants [46]. In this process, the plant roots interact with the Gram-negative soil bacteria, known as rhizobia, which through a molecular dialogue between these two partners, induce the formation of a new structure, the nodule, where the rhizobia gain the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. Symbiotic development includes changes in gene expression, suppression of defense mechanisms, induction of root cell division, and formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules. Because this is an expensive process for the plant, the establishment of symbiosis is highly regulated. Inhibition of nitrogen fixation, inhibition of symbiosis when interacting with incompatible or non-fixing bacteria, and control of the number of nodules are three of the essential regulatory mechanisms that match the degree of nodulation to the needs of the plant [47].

Although most of the CrRLK1Ls have been studied in A. thaliana, little is known about these proteins in other plant models, including legumes. Therefore, our knowledge is very limited about the function of CrRLK1Ls during the legume-rhizobia symbiosis. To address this gap, we first performed a robust phylogenetic analysis of the CrRLK1L subfamily members of more than 60 plant species, including four species of legumes. We compared the gene features and expression profiles of CrRLK1Ls between different organs in four legumes and A. thaliana and demonstrated that some CrRLK1L genes are expressed in legume nodules. Among these are eight genes that were differentially expressed over the course of nodule development in P. vulgaris roots inoculated with rhizobia. This study provides a robust and comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the CrRLK1L subfamily and unveils, for the first time, relevant information about the presumed role of this receptor subfamily in legume–rhizobia symbiosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of CrRLK1 Subfamily Proteins in 62 Plant Species

To identify all CrRLK1L proteins in 61 plant genomes available in the Phytozome v12.1 database (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov) [48] and in the Lotus japonicus L. genome (https://lotus.au.dk/) [49], BLASTP searches using the A. thaliana CrRLK1L protein sequences as query were performed. In both databases, default settings for e-values (e−1 value) and the number of hit sequences (100 hits) were used. To confirm that the sequences were part of the CrRLK1L family, they were analyzed with Pfam 32.0 (http://pfam.xfam.org) [50] and filtered by the presence of the characteristic malectin-like and kinase domains in this subfamily. A total of 1050 proteins sequences were confirmed as CrRLK1L proteins and downloaded from both databases.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the CrRLK1L Subfamily

All 1050 protein sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm [51] followed by a manual optimization of the misaligned sequences in the AliView editor [52]. An approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree [53] was created for edited sequence alignment with IQ-TREE 1.6.12 [54], using the JTT+F+R10 substitution model with 1000 bootstraps and default parameters. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the relation between the number of CrRLK1L genes and the genome size or the number of CrRLK1L genes between the total number of genes, for the analyzed species.

To explore the possibility that CrRLK1Ls participate in legume–rhizobia symbiosis, a phylogenetic analysis of the CrRLK1L protein sequences of P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, Glycine max (L.), Merr. and M. truncatula was performed. To compare legumes with other model plants, we selected A. thaliana as the model plant in which the CrRLK1Ls genes have been more studied, and Physcomitrella patens (Hedw.) Bruch & Schimp as a representative moss species. All of these plant species have complete accurate genome and proteome annotations in the Phytozome and Lotus Base databases, as well as available expression profile data. Alignment of CrRLK1L protein sequences from these six species was also done using the MUSCLE algorithm [51] within the AliView alignment editor [52], and a manual optimization of the misaligned regions. Then, an approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic unrooted tree [53] was established for full-length aligned protein sequences with IQ-TREE 1.6.12 [54] with a JTT+F+R7 substitution model and 1000 bootstraps for reliability, using the default parameters. The clades and subclades of both phylogenetic trees were analyzed using MEGA7 [55].

2.3. Analysis of CrRLK1L Protein Motif Conservation in Legumes and A. thaliana

Protein motif conservation of the 150 CrRLK1Ls present in A. thaliana and in the four legumes analyzed were determined using the conserved sequence motif analyzer MEME (http://meme-suite.org) [56]. The analysis was done using the full-length amino acid sequences, setting the maximum number to 15 motifs, the number of expected motifs to any number of repetitions, and the length of the motif to 10–200 amino acids. The other parameters were kept as default. To calculate the theoretical molecular weight and isoelectric point, the 150 proteins sequences were submitted to the ExPASy web server (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) [57].

2.4. Gene Structure, Chromosomal Localization, and Synteny Analysis of the CrRLK1L Gene Subfamily of Legumes, A. thaliana, and Sorgum bicolor (L.), Moench

The gene structure and chromosomal localization data of the 33 P. vulgaris, 18 L. japonicus, 46 G. max, 36 M. truncatula, 17 A. thaliana, and 14 S. bicolor CrRLK1L genes were retrieved from the Phytozome v12.1 [48] database and Lotus Base [49]. S. bicolor was used to evaluate the differences between eudicot and monocot CrRLK1L genes features, since it is a monocot model with complete genome sequence and gene expression information. The gene structure map for each species was represented using the free resource Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/Gsds_about.php). For the chromosome distribution, data were uploaded into the free resource PhenoGram Plot (http://visualization.ritchielab.org/phenograms/plot) [58]. For synteny analysis, the protein sequences and annotation files of the full genomes of P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, G. max, and L. japonicus were downloaded from the previously mentioned databases [48,49]. For each case, an m8 format BLASTP file and a simplified gff file were used as inputs to the collinearity scanner toolkit MCScanx (http://chibba.pgml.uga.edu/mcscan2/) [59] to determine synteny between CrRLK1L genes in the legume species and to compare it with that in A. thaliana.

2.5. In Silico Analysis of the CrRLK1L Gene Family Expression in Legumes, A. thaliana, and P. patens

Expression profiles of the 33 members of the P. vulgaris CrRLK1L gene subfamily were retrieved from the Common bean Gene Expression Atlas, PvGEA (https://plantgrn.noble.org/PvGEA/) [60]. L. japonicus expression profile data were downloaded from the L. japonicus reference genome transcript explorer in Lotus Base [49]. M. truncatula expression profile data were downloaded from the M. truncatula Gene Expression Atlas (MtGEA) [61,62] by BLASTN. The expression profiles of the 46 G. max, 17 A. thaliana, and 6 P. patens CrRLK1L genes were obtained from the Bio-Analytic Resource for Plant Biology (BAR) [61,63,64,65]. The distribution and abundance of the expression profile of the genes were presented in heatmaps with the function heatmap.2 of the gplot package [66] using R. To identify the shared genes expressed in nodules of P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and G. max, a Venn diagram was drawn using the Venn diagram drawing tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

2.6. Plant Growth Conditions and RT-qPCR Assays

Common bean (P. vulgaris cv. Negro Jamapa) seeds were surface-sterilized and germinated for 2 days (dpg) at 28 °C in darkness. For RT-qPCR accumulation profile analysis during nodulation, 2 dpg seedlings were transplanted into pots with vermiculite and inoculated with Rhizobium tropici CIAT899 at an OD600 of 0.05, or only with Fahraeus media as mock. Roots were harvested at 5, 7, 14, and 21 days post-inoculation (dpi). The tissues selected for RT-qPCR were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until RNA extraction. RNA was isolated from the frozen tissues using Trizol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified by electrophoresis and the concentration was assessed using a NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To eliminate DNA contamination, the RNA samples were incubated with RNase-free DNase (1 U/µL; Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using Thermo Scientific RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/µL, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), with 200 ng of DNA-free RNA as template and following the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR assays were performed using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), in a real time PCR system (QuantStudio 5; Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with the following thermal cycle: 95 °C for 10 min, 30 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 60 s. Experiments were normalized with the reference gene Elongation Factor 1α (EF1 α) [67]. Relative expression values were calculated using the formula 2−ΔCt, where the cycle threshold value ΔCt is equal to the Ct of the gene of interest minus the Ct of the reference gene. Three biological replicates with three technical repeats were performed for each dataset. The gene-specific oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Materials Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of CrRLK1L Proteins in Diverse Plant Species

Previous reports identifying CrRLK1L subfamily receptors have focused on a few model species, such as A. thaliana and Oryza sativa L. To study the potential function of this receptor subfamily in legume-rhizobia symbiosis, we expanded our analysis of these proteins to other plant species by searching for CrRLK1Ls in 61 plant genomes deposited in Phytozome v12.1 and also in the L. japonicus genome. We searched for CrRLK1L homologs in the 62 species, followed by a domain analysis of the identified proteins to confirm the presence of the characteristic malectin-like and kinase domains of the CrRLK1L subfamily. We identified a total of 1050 CrRLK1L proteins in 57 of the 62 species analyzed. None of the five chlorophyte genomes we searched had a significant hit related to the CrRLK1L subfamily. By contrast, at least one CrRLK1L was encoded in every land plant genome in our analysis (Table S2). The complete data are summarized in Table S2, and the IDs of the 1050 CrRLK1L proteins are listed in Table S3.

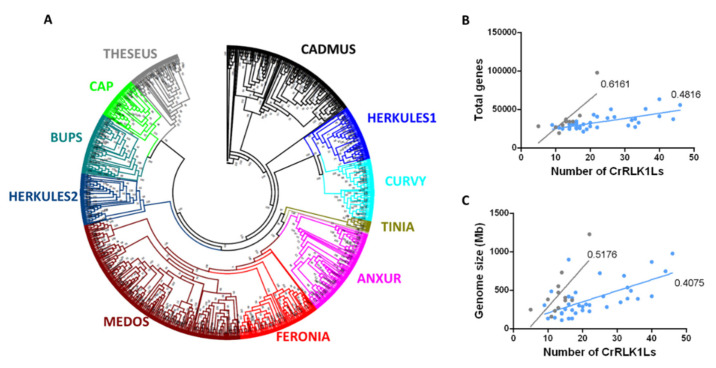

Based on a phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences of these 1050 proteins, we established that they are distributed into 11 clades (Figure 1A, Figure S1). One of these clades consisted exclusively of CrRLK1Ls of the most ancient plant species included in this analysis: three bryophytes (Marchantia polymorpha L., P. patens, and Sphagnum fallax (H.Klinggr) H.Klinggr) and a clubmoss (Selaginella moellendorffii Hieron). This clade was named TINIA (after the first of the Etruscan gods and father of Herkules), following the mythological nomenclature used for other CrRLK1L clades (Figure 1A, Figure S1). Of the remaining ten clades, nine were named according to the nomenclature employed for the A. thaliana protein belonging to each clade (Figure 1A, Figure S1). A clade carrying the two uncharacterized A. thaliana CrRLK1Ls was named CADMUS (after the Etruscan king founder of Thebes) (Figure 1A, Figure S1). Eudicots had an average of 22 CrRLK1L proteins, whereas monocots had fewer, with an average of 13 (Figure 1A, Figure S1, Table S1). This difference in the number of CrRLK1Ls could be associated with the greater size of eudicot genomes compared to those of monocots, since there is a moderate correlation between the number of CrRLK1Ls and the genome size and the number of total genes in both groups (eudicots, r = 0.55 and r = 0.47, respectively; monocots, r = 0.51 and r = 0.62, respectively) (Figure 1B,C). These data suggest that the CrRLK1L subfamily probably appeared during the transition from chlorophytes to embryophytes, and that the number of members increased along with the size of the genome and the total number of genes during evolution.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among 1050 CrRLK1L proteins and the relationship between CrRLK1L number versus gene size and gene number. (A) Unrooted approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree inferred from the 1050 CrRLK1L proteins present in 57 plant species. The clades, indicated in different colors, are named based on the A. thaliana CrRLK1L names. The CADMUS clade contains uncharacterized CrRLK1Ls from A. thaliana, and the TINIA clade corresponds to a clade formed only with the CrRLK1L proteins of S. moellendorffii, S. fallax, P. patens, and M. polymorpha. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE software with the JTT+F+R10 substitution model with 1000 bootstrap iterations. (B) Relationship between total number of genes within the genome and number of CrRLK1L genes for monocotyledons (gray) and eudicots (blue). (C) Relationship between genome size and number of CrRLK1L genes for monocotyledons (gray) and eudicots (blue).

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the CrRLK1L Subfamily in Legumes, A. thaliana, and P. patens

Legumes have the ability to establish a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia and form nitrogen-fixing nodules. To explore the possibility that CrRLK1Ls participate in legume–rhizobia symbiosis, we constructed a phylogenetic tree that included all the CrRLK1Ls of four model legumes (L. japonicus, M. truncatula, G. max, and P. vulgaris), A. thaliana, and the moss P. patens.

As expected, all five P. patens proteins were placed in the basal TINIA clade, separated from the proteins of the four legumes and A. thaliana (Figure S2). The remaining CrRLK1L proteins were distributed among ten clades, each containing at least one CrRLK1L from A. thaliana and one to several proteins from the legumes. Although no clade was confined exclusively to legumes, some clades had more members in the legumes than are present in A. thaliana. In this context, the MEDOS clade was particularly interesting because P. vulgaris, M. truncatula, and G. max each have a relatively large number of these proteins (16, 18, and 24, respectively), whereas A. thaliana has only four (Table 2). These observations indicate that although there is no group of proteins exclusively associated with legumes, there is at least a four-fold increase in the number of CrRLK1L proteins in this plant family compared to A. thaliana, particularly in the MEDOS clade.

Table 2.

Transcript lengths and protein properties of the CrRLK1L subfamily members in P. vulgaris, G. max, A. thaliana, L. japonicus, and M. truncatula.

| Gene ID * | Gene Name | CDS Length, bp | Protein Length, aa | iP | Molecular Weight, kDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. vulgaris | |||||

| Phvul.006G102700 | ANX1 | 2589 | 862 | 5.71 | 95.82 |

| Phvul.007G188300 | ANX2 | 2589 | 862 | 5.6 | 96 |

| Phvul.011G210400 | BUPS | 2670 | 889 | 5.41 | 97.19 |

| Phvul.003G188000 | CAP | 2469 | 822 | 5.91 | 92.06 |

| Phvul.004G109500 | CRV1 | 2505 | 834 | 5.49 | 92.38 |

| Phvul.007G074000 | CRV2 | 2535 | 844 | 5.7 | 93.64 |

| Phvul.008G081000 | FER1 | 2700 | 899 | 5.99 | 98.37 |

| Phvul.008G082400 | FER2 | 2697 | 898 | 6.67 | 98.1 |

| Phvul.005G139800 | HERK1A | 2514 | 837 | 5.64 | 92.51 |

| Phvul.008G000200 | HERK1B | 2472 | 823 | 5.38 | 92.18 |

| Phvul.011G069600 | HERK1C | 2514 | 837 | 5.79 | 92.94 |

| Phvul.006G127900 | HERK2 | 2547 | 848 | 7.3 | 93.01 |

| Phvul.004G038800 | MEDOS1A | 2676 | 891 | 7.29 | 99.43 |

| Phvul.004G039200 | MEDOS1B | 2235 | 744 | 7.05 | 83.82 |

| Phvul.004G039600 | MEDOS1C | 2598 | 865 | 5.78 | 96.98 |

| Phvul.004G039700 | MEDOS1D | 2406 | 801 | 5.79 | 90.35 |

| Phvul.004G039800 | MEDOS1E | 2442 | 813 | 5.99 | 92.04 |

| Phvul.004G039900 | MEDOS1F | 2490 | 829 | 6.51 | 93.64 |

| Phvul.004G040000 | MEDOS1G | 2460 | 819 | 7.31 | 92.32 |

| Phvul.004G040300 | MEDOS1H | 1824 | 607 | 6.26 | 68.13 |

| Phvul.004G040901 | MEDOS1I | 1353 | 450 | 8.46 | 50.59 |

| Phvul.004G039400 | MEDOS2A | 2463 | 820 | 5.99 | 92.31 |

| Phvul.008G030200 | MEDOS3A | 2595 | 864 | 6.15 | 96.81 |

| Phvul.008G030400 | MEDOS3B | 2517 | 838 | 6.24 | 93.86 |

| Phvul.008G030700 | MEDOS3C | 2577 | 858 | 6.28 | 96.37 |

| Phvul.008G030800 | MEDOS3D | 2601 | 866 | 4.83 | 97.08 |

| Phvul.003G038700 | MEDOS4A | 2385 | 794 | 8.67 | 89.03 |

| Phvul.003G038800 | MEDOS4B | 2523 | 840 | 5.95 | 93.94 |

| Phvul.005G085600 | THE1 | 2523 | 840 | 5.93 | 92.73 |

| Phvul.011G148700 | THE2 | 2538 | 845 | 5.87 | 93.05 |

| Phvul.003G239300 | CAD1 | 2499 | 832 | 6.63 | 93.06 |

| Phvul.003G239400 | CAD2 | 2589 | 862 | 8.33 | 96.18 |

| Phvul.003G239500 | CAD3 | 2586 | 861 | 5.86 | 96.32 |

| G. max | |||||

| Glyma.03G247800 | ANXUR1 | 2610 | 869 | 5.24 | 96.22 |

| Glyma.10G163200 | ANXUR2 | 2589 | 862 | 5.67 | 95.95 |

| Glyma.19G245800 | ANXUR3 | 2601 | 866 | 5.31 | 95.71 |

| Glyma.20G225800 | ANXUR4 | 2532 | 843 | 5.8 | 93.73 |

| Glyma.12G235900 | BUPS1 | 2637 | 878 | 5.77 | 96.33 |

| Glyma.13G201400 | BUPS2 | 2610 | 869 | 5.85 | 95.29 |

| Glyma.17G102600 | CAP1 | 2586 | 861 | 6.55 | 95.69 |

| Glyma.09G273300 | FERONIA1 | 2691 | 896 | 5.64 | 98.07 |

| Glyma.18G215800 | FERONIA2 | 2685 | 894 | 5.66 | 97.76 |

| Glyma.12G074600 | HERKULES1A | 2514 | 837 | 5.86 | 92.74 |

| Glyma.15G042900 | HERKULES1B | 2226 | 741 | 7.93 | 81.93 |

| Glyma.U033500 | HERKULES1C | 2436 | 811 | 6.5 | 89.91 |

| Glyma.09G024700 | HERKULES2 | 2559 | 852 | 5.59 | 93.59 |

| Glyma.02G121900 | MEDOS1A | 2463 | 820 | 8.23 | 92.15 |

| Glyma.02G122000 | MEDOS1B | 1944 | 647 | 5.81 | 72.73 |

| Glyma.02G196000 | MEDOS1C | 2481 | 826 | 5.83 | 93.46 |

| Glyma.08G248900 | MEDOS2A | 2529 | 842 | 6.25 | 92.88 |

| Glyma.08G249200 | MEDOS2B | 2616 | 871 | 6.24 | 96.62 |

| Glyma.08G249400 | MEDOS2C | 2373 | 790 | 6.02 | 88.62 |

| Glyma.13G054400 | MEDOS3A | 2691 | 896 | 6.11 | 99.53 |

| Glyma.13G053800 | MEDOS3B | 2109 | 702 | 6.44 | 77.97 |

| Glyma.13G053700 | MEDOS3C | 2460 | 819 | 5.63 | 91.47 |

| Glyma.13G053600 | MEDOS3D | 2685 | 894 | 5.9 | 99.35 |

| Glyma.13G054200 | MEDOS3E | 2364 | 787 | 8.48 | 88.74 |

| Glyma.13G054300 | MEDOS3F | 2535 | 844 | 5.98 | 94.104 |

| Glyma.18G269900 | MEDOS4A | 2610 | 869 | 6.26 | 97.24 |

| Glyma.18G270100 | MEDOS4B | 2607 | 868 | 6.09 | 97.39 |

| Glyma.18G270600 | MEDOS4C | 3372 | 1123 | 5.77 | 124.54 |

| Glyma.18G270700 | MEDOS4D | 2574 | 857 | 6.25 | 95.77 |

| Glyma.18G270900 | MEDOS4E | 2628 | 875 | 5.82 | 97.45 |

| Glyma.18G271000 | MEDOS4F | 2592 | 863 | 5.9 | 96.86 |

| Glyma.18G271100 | MEDOS4G | 2652 | 883 | 6.02 | 98.05 |

| Glyma.18G270800 | MEDOS4I | 2730 | 909 | 5.98 | 102.67 |

| Glyma.18G271200 | MEDOS4J | 2550 | 849 | 5.83 | 95.14 |

| Glyma.19G033100 | MEDOS5A | 3561 | 1186 | 6.49 | 133.95 |

| Glyma.U027000 | MEDOS5B | 2364 | 787 | 8.48 | 88.76 |

| Glyma.U027100 | MEDOS5C | 2460 | 819 | 5.75 | 91.75 |

| Glyma.12G148200 | THESEUS1 | 2541 | 846 | 5.68 | 93.19 |

| Glyma.12G220400 | THESEUS2 | 2070 | 689 | 6.44 | 75.72 |

| Glyma.05G099900 | CAD1 | 2382 | 793 | 6.3 | 88.42 |

| Glyma.05G100000 | CAD2 | 2517 | 838 | 5.58 | 94.02 |

| Glyma.09G133000 | CAD3 | 2457 | 818 | 7.04 | 99.92 |

| Glyma.10G231500 | CAD4 | 2481 | 826 | 7.94 | 91.86 |

| Glyma.16G179600 | CAD5 | 2322 | 773 | 8.81 | 86.06 |

| Glyma.17G166200 | CAD6 | 2523 | 840 | 5.8 | 93.93 |

| Glyma.20G162300 | CAD7 | 2523 | 840 | 8.17 | 93.19 |

| A. thaliana | |||||

| AT3G04690 | ANX1 | 2837 | 895 | 6.47 | 98.16 |

| AT5G28680 | ANX2 | 2577 | 850 | 6.54 | 94.06 |

| AT4G39110 | BUPS1 | 2637 | 858 | 5.76 | 94.31 |

| AT2G21480 | BUPS2 | 2616 | 873 | 5.66 | 97.18 |

| AT5G61350 | CAP | 2529 | 880 | 5.92 | 97.96 |

| AT2G39360 | CRV | 2683 | 815 | 6.13 | 91.33 |

| AT3G51550 | FER | 3298 | 830 | 5.82 | 91.48 |

| AT5G59700 | HERK/ANJ | 3041 | 849 | 5.76 | 93.96 |

| AT3G46290 | HERK1 | 3158 | 855 | 5.91 | 93.31 |

| AT1G30570 | HERK2 | 2550 | 842 | 6.16 | 92.7 |

| AT5G39000 | MEDO2 | 2622 | 878 | 5.75 | 96.52 |

| AT5G38990 | MEDOS1 | 2785 | 871 | 5.51 | 95.95 |

| AT5G39020 | MEDOS3 | 2442 | 829 | 6.5 | 91.97 |

| AT5G39030 | MEDOS4 | 2421 | 824 | 5.65 | 91.84 |

| AT5G54380 | THE1 | 2789 | 834 | 5.7 | 93.39 |

| AT5G24010 | CAD1 | 2821 | 813 | 7.6 | 90.64 |

| AT2G23200 | CAD2 | 2633 | 806 | 5.97 | 90.68 |

| L. japonicus | |||||

| Lj1g3v4996200 | ANXUR | 2592 | 863 | 5.46 | 95.4 |

| Lj0g3v0115159 | BUPS | 2643 | 880 | 5.93 | 96.29 |

| Lj3g3v3639930 | CURVY1 | 2472 | 823 | 6.08 | 90.91 |

| Lj3g3v3639940 | CURVY2 | 2121 | 706 | 5.98 | 77.77 |

| Lj1g3v2533770 | FERONIA | 2094 | 697 | 5.96 | 75.96 |

| Lj0g3v0249939 | HERKULES1A | 2514 | 837 | 5.41 | 91.74 |

| Lj3g3v3132890 | HERKULES1B | 1848 | 615 | 6.61 | 67.66 |

| Lj6g3v1641160 | HERKULES2A | 2532 | 843 | 5.77 | 92.66 |

| Lj6g3v1641170 | HERKULES2B | 2532 | 843 | 5.77 | 92.66 |

| Lj2g3v1102970 | MEDOS1 | 2676 | 891 | 6.75 | 97.76 |

| Lj2g3v1226730 | MEDOS2 | 1542 | 513 | 7.59 | 58.1 |

| Lj2g3v1226740 | MEDOS3 | 2466 | 821 | 6.93 | 92.49 |

| Lj2g3v1226750 | MEDOS4 | 2277 | 758 | 5.49 | 84.89 |

| Lj0g3v0346559 | THESEUS | 2535 | 844 | 5.54 | 92.59 |

| Lj0g3v0151929 | CAD1 | 1554 | 517 | 8.87 | 57.31 |

| Lj2g3v0322770 | CAD2 | 2493 | 830 | 6.46 | 92.25 |

| Lj2g3v1902230 | CAD3 | 2169 | 722 | 8.75 | 80.67 |

| Lj5g3v1988700 | CAD4 | 2535 | 844 | 6.98 | 94.3 |

| M. truncatula | |||||

| Medtr1g080740 | ANX1 | 2607 | 868 | 6.15 | 96.86 |

| Medtr7g115300 | ANX2 | 2619 | 872 | 5.32 | 97.04 |

| Medtr8g037700 | BUPS1 | 2406 | 801 | 5.94 | 96.47 |

| Medtr4g109010 | CAP1 | 3459 | 1152 | 6.5 | 129.96 |

| Medtr4g111925 | FER1 | 2106 | 701 | 6.5 | 76.58 |

| Medtr7g073660 | FER2 | 2700 | 899 | 5.89 | 97.98 |

| Medtr4g061930 | HERK1A | 2523 | 840 | 5.82 | 93.13 |

| Medtr2g096160 | HERK1B | 2544 | 847 | 5.57 | 92.93 |

| Medtr4g061833 | HERK1C | 2523 | 840 | 5.82 | 93.13 |

| Medtr2g030310 | HERK2 | 2628 | 875 | 5.89 | 96.34 |

| Medtr6g015805 | MEDOS1A | 2703 | 900 | 6.8 | 100.32 |

| Medtr5g047120 | MEDOS2A | 2430 | 809 | 7.09 | 92.07 |

| Medtr5g047070 | MEDOS2B | 1707 | 568 | 6.23 | 64.53 |

| Medtr7g015390 | MEDOS3A | 2670 | 889 | 6.25 | 101.42 |

| Medtr7g015550 | MEDOS3B | 2667 | 888 | 5.92 | 100.81 |

| Medtr7g015670 | MEDOS3C | 2679 | 892 | 5.75 | 101.65 |

| Medtr7g015510 | MEDOS3D | 2667 | 888 | 5.84 | 100.38 |

| Medtr7g015240 | MEDOS3E | 2529 | 842 | 6.16 | 96.25 |

| Medtr7g015280 | MEDOS3F | 2577 | 858 | 6.44 | 97.98 |

| Medtr7g015420 | MEDOS3G | 3417 | 1138 | 6.02 | 130.78 |

| Medtr4g052290 | MEDOS3H | 2658 | 885 | 7.8 | 101.29 |

| Medtr7g015250 | MEDOS3I | 2733 | 910 | 6.16 | 103.04 |

| Medtr7g015310 | MEDOS3J | 2622 | 873 | 6.08 | 98.98 |

| Medtr7g015230 | MEDOS3K | 2652 | 883 | 6.91 | 100.7 |

| Medtr7g015320 | MEDOS3L | 2637 | 878 | 7.58 | 99.19 |

| Medtr7g015620 | MEDOS3M | 2064 | 687 | 8.81 | 78.9 |

| Medtr5g047060 | MEDOS4A | 2502 | 833 | 5.21 | 94.17 |

| Medtr5g047110 | MEDOS4B | 2454 | 817 | 5.5 | 92.57 |

| Medtr6g048090 | OG1 | 2385 | 794 | 6.84 | 88.69 |

| Medtr1g100110 | OG2 | 2445 | 814 | 6.57 | 91.66 |

| Medtr2g080220 | THE1 | 2532 | 843 | 5.61 | 92.73 |

| Medtr4g095042 | CAD1 | 2556 | 851 | 5.85 | 94.87 |

| Medtr4g095012 | CAD2 | 2460 | 819 | 6.12 | 91.27 |

| Medtr4g095032 | CAD3 | 2361 | 786 | 5.82 | 87.7 |

| Medtr1g040073 | CAD4 | 2256 | 751 | 6.23 | 83.97 |

| Medtr8g467150 | CAD5 | 2277 | 758 | 7.33 | 85.16 |

* Phytozome ID. bp: base pairs. CDS: coding sequence. aa: amino acids. iP: isoelectric point. kDa: kiloDalton.

3.3. Features of the CrRLK1L Subfamily Proteins in Legumes and A. thaliana

Since we identified no CrRLK1L clade that was exclusive to legumes, we wondered whether some of these proteins, which have important functions in other plant processes, could have been recruited to function in legume-rhizobia symbiosis. To assess this possibility, we analyzed the molecular characteristics of the CrRLK1L proteins of the four legumes previously examined and A. thaliana. There are 33 CrRLK1L proteins encoded in the P. vulgaris genome, whereas in A. thaliana there are 17, in both cases distributed among ten different clades. M. truncatula, G. max, and L. japonicus have 36, 46, and 18 CrRLK1Ls, respectively, scattered among nine clades (Figure S2).

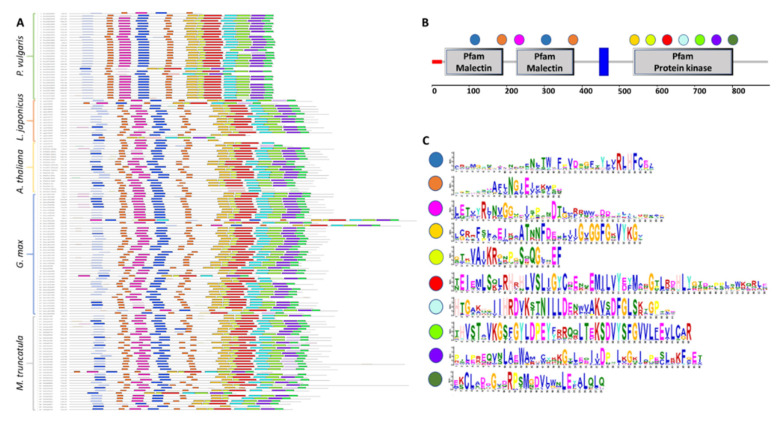

The CrRLK1L proteins are defined by the presence of a malectin-like domain in the amino-terminal region and a kinase domain in the carboxy-terminal region. To characterize these conserved motifs, the CrRLK1L sequences of the four legumes under study and A. thaliana were examined using MEME software (Figure 2). In the 150 sequences analyzed, ten different motifs were identified; seven of these were located in the kinase domain, and only three in the malectin domain, two of them duplicated. The motifs located in the kinase domain were longer and more conserved than those in the malectin-like domain (Figure 2). No additional features were observed that could be associated with a given species or phylogenetic clade, beyond the particularities of individual proteins, such as shorter or longer amino acid sequences.

Figure 2.

CrRLK1L protein sequence conservation and characteristic motifs in legumes and A. thaliana. MEME was used to identify motifs in the 150 CrRLK1Ls from four legumes and A. thaliana. (A) Diagram of the motifs in the CrRLK1L protein sequences from P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, G. max, M. truncatula, and A. thaliana. Significant overrepresented motifs are graphically depicted by bars corresponding to their predicted position. (B) Localization of overrepresented motifs identified using MEME in the CrRLK1L protein domains. (C) Logo of the overrepresented motifs identified with MEME; the color code corresponds with that used in (A,B).

The 33 P. vulgaris CrRLK1L proteins ranged from 450 to 899 amino acids (aa) in length and 50.59 to 99.43 kDa in molecular weight (MW) (Table 2). The theoretical isoelectric point (iP) of most of the common bean proteins is slightly acidic (4.83 to 6.67), though seven proteins are slightly alkaline (7.05 to 8.67) (Table 2). The L. japonicus CrRLK1Ls showed similar features to those of common bean, with MWs of 57.31 to 97.76 kDa and lengths of 513 to 891 aa. Furthermore, most of the L. japonicus proteins have acidic iPs (5.93 to 6.98), whereas only three of them have alkaline iPs (7.59 to 8.87) (Table 2). The CrRLK1L proteins have a broader MW range in M. truncatula and G. max (64.53 to 130.78 and 72.73 to 133.95 kDa, respectively) and are longer (568 to 1152 aa and 647 to 1186 aa, respectively) than to those of P. vulgaris (Table 2). In M. truncatula, only five proteins have alkaline iPs (7.05 to 8.81), whereas the remaining 31 have acidic iPs (5.21 to 6.91) (Table 2). In G. max, eight of the proteins were alkaline (7.04 to 8.81) and 38 are acidic (5.24 to 6.55) (Table 2). In comparison to the legume proteins, the A. thaliana CrRLK1Ls have narrower ranges of MW (90.68 to 98.16 kDa) and length (806 to 895 aa). Only one A. thaliana protein has an alkaline iP (7.6), whereas 16 have a slightly acidic iP (5.51 to 6.54) (Table 2).

Despite high conservation of the CrRLK1L domains, there were some physicochemical differences between the legume proteins we studied and those of A. thaliana. This variation could be associated with the higher number of proteins observed in G. max, P. vulgaris, and M. truncatula compared to A. thaliana, which could have allowed more divergence of the proteins over time.

3.4. Chromosomal Localization and Synteny of CrRLK1L Genes in Legumes and A. thaliana

To compare the genome distributions of CrRLK1L genes in A. thaliana and in the four legumes under study, we used PhenoGram Plot to map the chromosome locations of the CrRLK1L genes in each plant species. The P. vulgaris CrRLK1L genes are distributed among seven of the 11 chromosomes, mainly on chromosomes four and eight (Figure S3A). The P. vulgaris MEDOS genes were mapped to chromosomes three (two genes), four (ten genes), and eight (four genes). M. truncatula and G. max have a similar gene distribution, the 46 G. max CrRLK1L genes are distributed among 14 of the 20 chromosomes, with two groups of MEDOS clade genes, one on chromosome 13 (six genes) and the other on chromosome 18 (eight genes) (Figure S3C). M. truncatula has 36 CrRLK1L genes, located on seven chromosomes, and two clusters of MEDOS clade genes on chromosomes five (four genes) and seven (12 genes) (Figure S3D). In the L. japonicus and A. thaliana genomes, CrRLK1L genes are distributed on five chromosomes, with only one small cluster, consisting of MEDOS genes, in each species, on chromosome two in L. japonicus (Figure S3B) and on chromosome five in A. thaliana (Figure S3E). Previously, we found that the MEDOS clade is absent in most monocots; therefore, we decided to also examine the distribution of the CrRLK1L genes in S. bicolor. In this species, all CrRLK1L genes were located on six chromosomes, and no clustering was observed (Figure S3F). These data suggest that there has been an expansion of the MEDOS genes in eudicots, and that some species have undergone greater expansion than others.

To further explore the evolutionary trajectories of the CrRLK1L genes, we evaluated the local synteny among the CrRLK1L genes in P. vulgaris, G. max, L. japonicus, M. truncatula, and A. thaliana. Chromosomal synteny was evaluated in these five species individually and also between species using MCScanx software. This analysis showed that four pairs of genes are syntenic in P. vulgaris, corresponding to 25% of the CrRLK1L genes. This was close to the percentage of gene synteny in the P. vulgaris genome overall (28.68%) (Figure S4, Table S4). In L. japonicus, only one pair of syntenic genes was identified, corresponding to 11% of CrRLK1L genes. Despite being lower than the CrRLK1L gene synteny in P. vulgaris, this percentage is above the median for the L. japonicum genome overall (4.74%) (Figure S4, Table S4). In G. max, 21 pairs of the CrRLK1L genes are syntenic, corresponding to 25 different genes (54.35% of the CrRLK1L genes). This gene synteny is slightly low given that 68.13% of all the genes in G. max genome are syntenic (Figure S4, Table S4). In A. thaliana, two pairs of genes have synteny, which corresponds to 23.53% of the CrRLK1Ls, similar to the 27.1% synteny of the A. thaliana genome overall (Figure S4, Table S4).

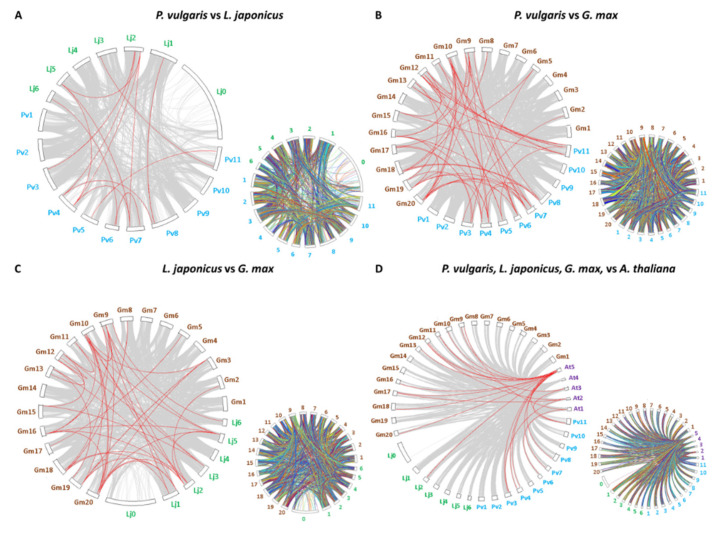

Collinearity of genes was also examined between pairs of legume species that develop determinate nodules, namely P. vulgaris, G. max, and L. japonicus. The results indicate that 35 CrRLK1L genes have collinearity between P. vulgaris and G. max, 12 genes between P. vulgaris and L. japonicus, and 20 genes between L. japonicus and G. max (Figure 3A–C, Table S4). Collinearity between the CrRLK1Ls of these three legumes versus A. thaliana was also explored. This analysis revealed 24 legume genes that are syntenic to those of A. thaliana: 9 from P. vulgaris, 1 from L. japonicus, and 14 from G. max (Figure 3A–C, Table S4). We noted that in most of the syntenic gene pairs identified, the genes belong to the same clade. Thus, some FER genes in P. vulgaris are syntenic to FER genes in L. japonicus and G. max, and the same was true for some of the MEDOS and HERK genes (Figure 3A–C, Table S4). Moreover, some of the genes maintain this collinearity between legumes and A. thaliana. These data strongly suggest that these genes are orthologous.

Figure 3.

Synteny of the CrRLK1L genes in P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, G. max, and A. thaliana. MCScan software was used to analyze the syntenic correlation between species. (A) Synteny map of CrRLK1Ls between L. japonicus and P. vulgaris. (B) Synteny map of CrRLK1Ls between G. max and P. vulgaris. (C) Synteny map of CrRLK1Ls between L. japonicus and G. max. (D) Synteny map of CrRLK1Ls between A. thaliana and the three legumes examined. Chromosome numbers are indicated outside each figure as follows: in turquoise, P. vulgaris; in green, L. japonicus; in brown, G. max; and in purple, A. thaliana. The smaller synteny maps to the right of each image represent the synteny of all the genes in the genomes compared here.

3.5. Exon–Intron Structure of CrRLK1L Genes in Legumes and A. thaliana

To analyze the structural organization and evolution of the CrRLKL1L genes following their duplication, we analyzed the exon–intron distribution in these genes in P. vulgaris, M. truncatula, G. max, L japonicus, and A. thaliana, using Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 software for better visualization (Figure 4). Most of the CrRLKL1L genes in P. vulgaris have no introns (26 genes), though four of them have one intron (PvCRV2, PvFER2, PvHERK1C, and PvTHE1) and three have two introns (PvCRV1, PvHERK1B, and PvTHE2) (Figure 4A). In L. japonicus, half of the CrRLK1L genes have no introns, two have one intron (LjCRV2 and LjMEDOS3), three have two introns (LjFER, LjHERK2B, and LjMEDOS4), and one has seven introns (LjMEDOS1) (Figure 4B). More than half of the G. max CrRLK1L genes have no introns, and 17 genes have one to seven introns (GmHERK1A, GmHERK1B, GmHERK1C, GmHERK2, GmMEDOS1B, GmMEDOS2C, GmMEDOS3A, GmMEDOS3B, GmMEDOS3D, GmMEDOS4C, GmMEDOS4I, GmMEDOS4J, GmMEDOS5A, GmTHE1, GmTHE2, GmCAD1, and GmCAD3) (Figure 4C). In M. truncatula, more than half of the genes (19 genes) have no introns, and 16 of them possess one to three introns (MtANX1, MtCAP, MtFER1, MtHERK1A, MtHERK1B, MtMEDOS1A, MtMEDOS3C, MtMEDOS3D, MtMEDOS3G, MtMEDOS3I, MtMEDOS3L, MtMEDOS4B, MtTHE1, MtTHE2, MtCAD1, MtCAD2, and MtCAD3) (Figure 4D). Most of the 17 A. thaliana genes have no introns, with only four of them having one intron (AtANX1, AtANX2, AtFER, and AtHERK1) (Figure 4E). Although some intron conservation was detected among the five plants analyzed, in FER, HERK, and MEDOS genes, many of the legume CrRLK1L genes have more introns than the corresponding A. thaliana genes.

Figure 4.

Gene structure of the CrRLK1L subfamily genes in four legumes, A thaliana, and S. bicolor. The exon–intron structures of all CrRKL1L genes from (A) P. vulgaris, (B) L. japonicus, (C) G. max, (D) M. truncatula, (E) A. thaliana, and (F) S. bicolor were analyzed using the Gene Structure Display Server database. Exons (CDS), introns, and untranslated regions (UTRs) are represented according to the key. Gene names are highlighted in colors as follows: ANX in purple, BUPS in green, CAD in black, CAP in lime, CRV in blue, FER in red, HERK1 (ANJ) in blue, HERK2 in dark blue, MEDOS in brown, and THE in gray. Orange asterisks to the left of the names indicate genes with introns.

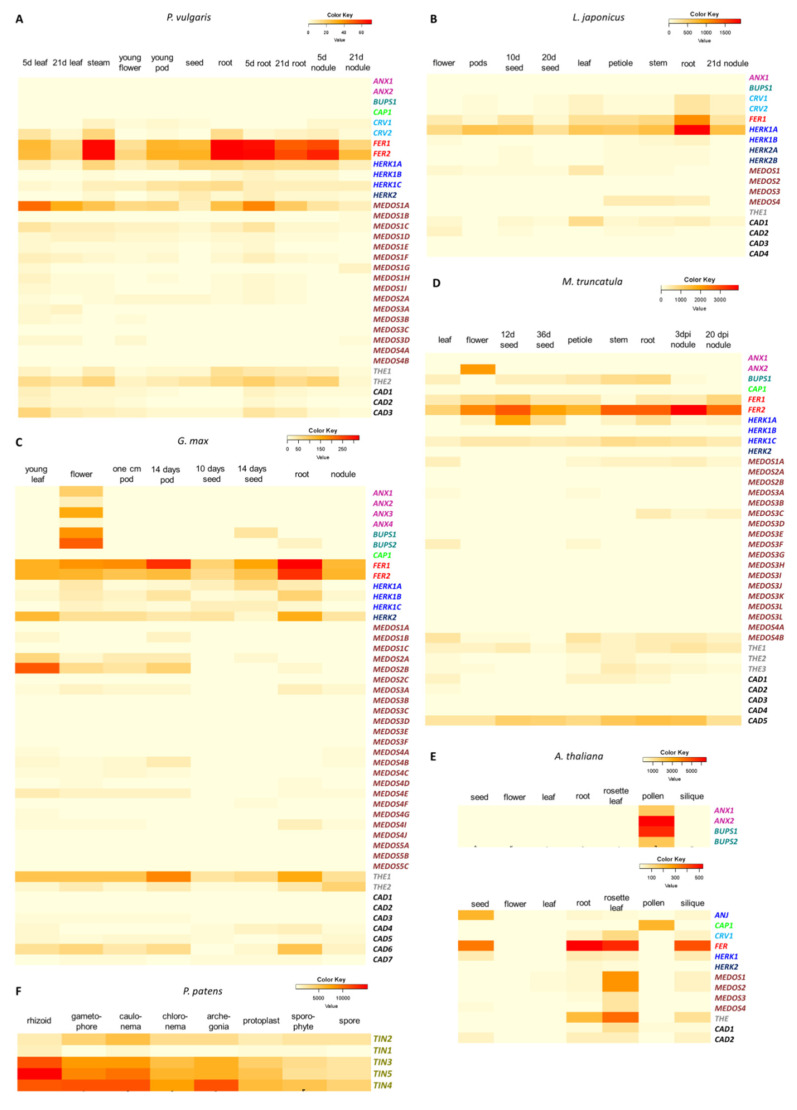

3.6. Analysis of the Expression Patterns of the CrRLK1L Genes in Legumes, A. thaliana, and P. patens

To evaluate the expression patterns of the CrRLK1Ls genes between different organs in four legumes and compare them with those in A. thaliana and P. patens, we retrieved and compared the expression data for P. vulgaris CrRLK1Ls from the common bean gene expression atlas (PvGEA) [60], for L. japonicus from the Lotus Base [49], for M. truncatula from MtGEA [61,62], and for G. max, A. thaliana, and P. patens from the BAR resource [61,63,64,65]. Expression data are represented as heat maps for each species (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gene expression profiles of CrRLK1Ls in four legumes, A. thaliana, and P. patens. Heat map of expression profiles of CrRLK1L in (A) P. vulgaris, (B) L. japonicus, (C) G. max, (D) M. truncatula, (E) A. thaliana, and (F) P. patens. Transcriptome data were extracted from the PvGEA, LotusBASE, and BAR databases. RPKM values are represented as color key codes above each heat map. Gene names are indicated as in the following color key; ANX in purple, BUPS in green, CAP in lime, CRV in blue, FER in red, HERK1 (ANJ) in blue, HERK2 in dark blue, MEDOS in brown, THE in gray, and CAD in black.

As described in the following sections, it was observed that most of the genes showed similar expression patterns in the four legumes examined (P. vulgaris, L japonicus, G. max, and M. truncatula) and in A. thaliana (FER, ANX, BUPS, CAP, HERK, THE, MEDOS, and CRV). Moreover, two genes differed in their expression patterns two to ten-fold in some tissues of the four legumes compared to their expression in A. thaliana (CAD and MEDOS). In addition, some CrRLK1L genes are expressed in legume nodules. Every P. patens CrRLK1L gene is expressed in all tissues analyzed; however, the levels of accumulation varied among the different tissues.

3.6.1. FER Genes Are Broadly Expressed in All Tissues in Four Different Plant Species

FER is the most studied gene of the CrRLK1L subfamily in A. thaliana, and it has key roles in diverse plant processes [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,68,69,70]. A. thaliana has only one FER gene, which is expressed in almost every tissue, with transcript levels being especially high in roots and rosette leaves (Figure 5E). The FER genes in P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and G. max are expressed at high levels in almost every tissue, similar to the expression pattern of AtFER in A. thaliana. The two FER genes identified in P. vulgaris (PvFER1 and PvFER2) are mainly expressed in roots and stems (Figure 5A). The single FER gene in L. japonicus (LjFER) shows expression in all tissues analyzed, with the highest levels in roots and stems (Figure 5B). G. max has two FER genes (GmFER1 and GmFER2), which are both expressed at high levels, mainly in roots and pods (Figure 5C). In M. truncatula, there are two FER genes, both widely expressed in the tissues analyzed. MtFER1 is mainly expressed in nodules, and seeds, while MtFER2 shows the highest expression levels in in nodule, root, and stem (Figure 5D). These expression patterns suggest a presumed conservation of FER gene function between A. thaliana and the legumes.

3.6.2. ANX, BUPS, and CAP Genes Are Expressed Only in A. thaliana Pollen Tubes and G. max Flowers

Five CrRLK1L genes in A. thaliana have been reported to be essential for pollen tube growth, AtANX1, AtANX2, AtBUPS1, AtBUPS2, and AtCAP [30,31,32,36]. The expression of these five genes in A. thaliana is limited to pollen tubes and shows the highest accumulation levels of all CrRLK1L genes (Figure 5E). Four of these genes (PvANX1, PvANX2, PvBUPS, and PvCAP) are present in P. vulgaris, but no expression was detected according to PvGEA (Figure 5A). In L. japonicus, there are only two of these genes, LjANX and LjCAP, and no expression was detected in any of the tissues evaluated (Figure 5B). By contrast, in G. max, there are four GmANX and two GmBUPS genes, all of which exhibit expression in flower (Figure 5C); GmCAP show no expression in any of the tissues analyzed (Figure 5C). M. truncatula have two ANX, one CAP, and one BUPS gene. MtANX1 and MtCAP1 show no expression in any tissue examined, MtANX2 are expressed exclusively in flowers, and MtBUPS1 is expressed in several tissues (Figure 5D). Since the PvGEA and Lotus Base databases do not include expression data for pollen tubes, the expression pattern observed for ANX, BUPS, and CAP genes in P. vulgaris and L. japonicum probably resembles that of A. thaliana, while in G. max and M. truncatula ANX and BUPS genes probably expanded their expression to other tissues beyond pollen.

3.6.3. HERK and THE Genes Are Expressed in Roots, Leaves, and Pods/Siliques

HERK and THE genes have been reported to regulate cell wall homeostasis in A. thaliana root and leaf, and HERK genes have also been reported to be essential for fertilization [4,33]. AtHERK1, AtHERK2, and AtTHE1 show highest levels of expression in rosette leaves, roots, and siliques (Figure 5E). In common bean, PvHERK1A and PvHERK1C are expressed in almost every tissue analyzed, mainly in roots and pods (Figure 5A), PvHERK1B and PvHERK2 show low expression, and PvTHE1 and PvTHE2 have the highest levels of expression in leaves, roots, and stems (Figure 5A). In L. japonicus, the four HERK genes show their highest expression in roots and nodules, followed by stem, leaves, and pods; LjTHE is not expressed (Figure 5B). In G. max, GmHERK1A and GmHERK1C are most strongly expressed in seeds, GmHERK1B in roots, and GmHERK2 shows the maximum expression in roots and leaves, and the two GmTHE genes are primarily expressed in pods and roots (Figure 5C). In M. truncatula, meanwhile MtHERK1A, MtHERK1C, and MtTHE1 are expressed in almost every tissues analyzed, mainly in roots and seeds, MtHERK1B and MtHERK2 are not expressed at all (Figure 5D). These data indicate that HERK and THE genes, which are expressed mostly in roots, leaves, and siliques in A. thaliana, have similar expression patterns in legumes, although the latter have many more copies of these genes.

3.6.4. MEDOS Genes Are Mostly Expressed in Leaves

It has recently been reported that MEDOS genes are important for regulating growth in the presence of metal ions in A. thaliana [38]. The four AtMEDOS genes are expressed mainly in rosette leaves (Figure 5E). In common bean, we detected 15 PvMEDOS genes. PvMEDOS1A is the third most expressed gene of all the CrRLK1L genes in this legume. PvMEDOS1B, PvMEDOS3C, PvMEDOS4A, and PvMEDOS4B show no expression in the analyzed tissues, and the other 10 PvMEDOS genes are expressed at low levels (Figure 5A). Despite these differences in transcript levels, PvMEDOS genes are mainly expressed in leaves and roots (Figure 5A). L. japonicus has four LjMEDOS genes. LjMEDOS1 is mainly expressed in leaves, LjMEDOS4 is mainly expressed in stem and petiole, and LjMEDOS2-3 genes show low expression in all tissues tested (Figure 5B). In G. max, there are 24 GmMEDOS genes, most of which show low or no expression in the tissues evaluated (14 of 24 genes). Nine GmMEDOS genes are mostly expressed in leaves and pods, whereas GmMEDOS4I is most strongly expressed in roots (Figure 5C). Eighteen MEDOS genes were founded in M. truncatula, of them only five (MtMEDOS1A, MtMEDOS3A, MtMEDOS3C, MtMEDOS3F, and MtMEDOS4B) show low expression levels, mainly in leaves, petioles, and roots (Figure 5D). These data suggest some conservation in the expression of MEDOS genes in leaves of legumes and A. thaliana. Nonetheless, some of these genes probably have additional functions, in legumes, which could be related to their expression in other tissues (Figure 5).

3.6.5. CRV Gene Expression Is Observed in Roots and Leaves, but Is Absent in G. max

CURVY (CRV) is a CrRLK1L receptor that is important for the development of leaves and seeds, as well as for the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth [37]. In A. thaliana, AtCRV is mainly expressed in rosette leaves, roots, and siliques (Figure 5E). In P. vulgaris there are two CRV genes, PvCRV1 and PvCRV2, both of which are expressed at very low levels, mostly in stems, leaves, and roots (Figure 5A). L. japonicus also has two LjCRV genes, both with low expression, mainly in roots, leaves, and nodules (Figure 5B). No CRV genes were identified in the G. max and M. truncatula genomes, suggesting a possible loss of these genes during their evolution (Figure 5C,D). These observations indicate that expression of CRV genes in roots and leaves is conserved; however, the decrease in CRV expression in legumes and the loss of this gene in G. max and M. truncatula suggest a gradual loss of function.

3.6.6. The Tissue Specificity of CAD Gene Expression Is Broader in Legumes Than in A. thaliana

The A. thaliana AtCAD1 and AtCAD2 genes, which have not yet been characterized, are mainly expressed in rosette leaves and roots (Figure 5E). The three PvCAD genes identified in common bean show low expression, mostly in leaves and inoculated roots (Figure 5A). L. japonicus has four LjCAD genes; LjCAD1 exhibits high expression in roots, leaves, and nodules, whereas the other three show low expression (Figure 5B). Seven GmCAD genes were detected in G. max: GmCAD1 and GmCAD2 show low expression; GmCAD3 and GmCAD5 are mainly expressed in pods, leaves, and flowers; GmCAD4 and GmCAD7 are predominantly expressed in seeds and roots; and GmCAD6 is expressed in roots, flowers, pods, and leaves (Figure 5C). Three of the five CAD genes in M. truncatula show no expression, MtCAD1 is expressed at low levels in leaves, petiole and stems, and MtCAD5 is expressed in most of the tissues, but mainly in stem, roots and nodules (Figure 5D). Thus, CAD genes are expressed in a wider range of tissues in legumes than in A. thaliana.

3.6.7. P. patens CrRLK1L Genes Are Widely but Differentially Expressed in All Tissues Tested

Our phylogenetic analysis showed that the five CrRLK1L genes in P. patens (PpTIN1-5) are clustered in a single distinct clade (Figure 1, Figure S1). All five genes are abundantly expressed in every tissue analyzed (Figure 5F). PpTIN1, PpTIN2, and PpTIN4 are mainly expressed in the rhizoid (an organ functionally related to the roots of land plants) and the caulonema (an organ necessary for colonization and nutrient acquisition). PpTIN3 is mostly expressed in the archegonia (the female reproductive organs in the moss) and in the caulonema. Maximum levels of PpTIN5 accumulation are observed in the caulonema and the gametophore (the tissue carrying the sex organs in moss) (Figure 5F). These variations in the expression patterns of the P. patens CrRLK1L genes suggest a certain amount of functional specialization of these genes in this moss, since the five genes probably originated from duplication of a single CrRLK1L gene.

3.6.8. Certain CrRLK1L Genes Are Differentially Expressed during Nodulation

We observed that almost none of the legume CrRLK1L genes are expressed specifically in symbiotic organs; however, some of them are highly expressed in these symbiotic organs (Figure 5). In P. vulgaris there are at least nine of these genes (PvCRV1, PvFER1, PvFER2, PvHERK1A, PvHERK1C, PvMEDOS1A, PvMEDOS1C, PvCAD3, and PvTHE2) (Figure 5A), nine genes in L. japonicus (LjCRV1, LjCRV2, LjFER1, LjHERK1A, LjHERK2A, LjHERK2B, LjMEDOS4A, LjCAD1, and LjCAD3) (Figure 5B), 10 genes in G. max (GmFER1, GmFER2, GmHERK1C, GmHERK2, GmMEDOS3A, GmMEDOS4, GmCAD1, GmCAD3, GmTHE1, and GmTHE2) and nine genes in M. truncatula (MtFER1, MtFER2, MtHERK1A, MtHERK1C, MtMED1A, MtMED3C, MtMEDOS4B, MtCAD5, and MtTHE1) (Figure 5C–D). We noticed that several of the 37 genes expressed in nodules are shared among the four legumes (Figure S5). FER1 is expressed in nodules in all four legumes, whereas five genes where shared between three different legumes: CAD3 is shared between P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and G. max; HERK1A is shared between P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and M. truncatula; while L. japonicus, G. max, and M. truncatula share MEDOS4; and FER2 and HERK1C are shared between P. vulgaris, G. max, and M. truncatula. Moreover, seven genes were founded in nodules in two legume pairs; P. vulgaris and L. japonicus nodules express CRV1, THE2 is expressed in nodules of P. vulgaris and G. max, and MEDOS1A in P. vulgaris and M. truncatula. Furthermore, HERK2A and CAD1 are expressed in G. max and L. japonicus, while MEDOS3 and THE1 are shared between G. max and M. truncatula. This comparative analysis also revealed four nodule-expressed genes that were exclusive to one legume (Figure S5).

These data together indicate that along with the highly conserved expression profiles of CrRLK1L genes in legumes, some of them are differentially expressed in nodules, suggesting a possible role of these genes in the nodulation process.

3.7. Expression of CrRLK1L Genes in P. vulgaris Nodules

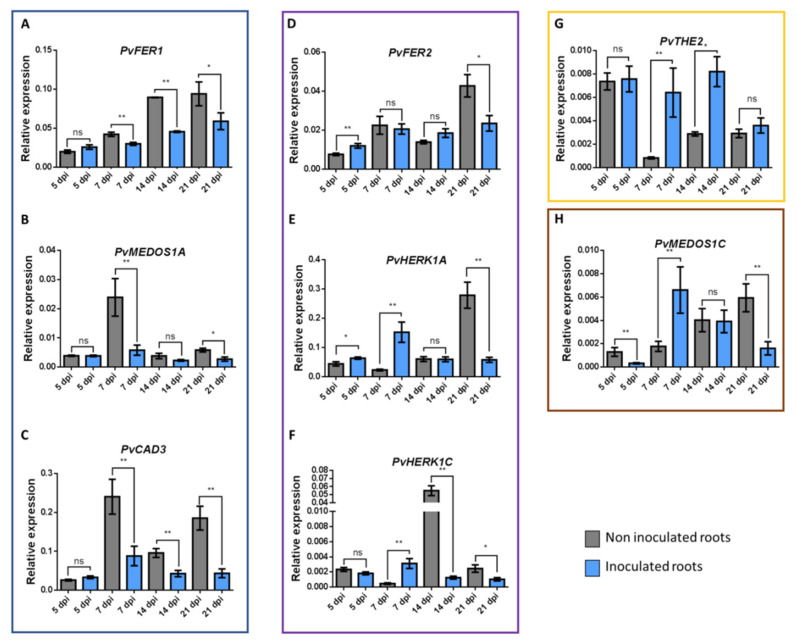

To validate the expression profile of some CrRLK1L genes in nodules that we observed in the PvGEA data [60], as well as to describe their expression patterns during different stages of nodulation, we selected eight P. vulgaris CrRLK1L genes for further investigation: PvFER1, PvFER2, PvHERK1A, PvHERK1C, PvMEDOS1A, PvMEDOS1C, PvTHE2, and PvCAD3. Expression of these genes was measured at four stages of the P. vulgaris-R. tropici symbiosis: 5, 7, 14, and 21 days post-inoculation (dpi) of wild-type roots. The eight genes were differentially expressed at the different stages of nodulation, corroborating their presumed role during nodulation in common beans.

These eight genes displayed four different expression profiles. Three genes were suppressed in at least one of the nodulation steps analyzed (blue box, Figure 6). PvFER1 and PvCAD3 showed reduced transcript accumulation in inoculated roots at 7, 14, and 21 dpi compared to uninoculated roots, whereas no differences were observed at 5 dpi (Figure 6A,B). PvMEDOS1A was downregulated at 7 and 21 dpi in inoculated roots but was expressed at similar levels regardless of inoculation at 5 and 14 dpi (Figure 6C). Three genes were upregulated in the early stages (5 or 7 dpi) but then suppressed in the later stages (14 or 21 dpi) (purple box, Figure 6); PvFER2 and PvHERK1C were upregulated in inoculated roots at 5 dpi, and PvHERK1A was upregulated at 5 and 7 dpi. At 21 dpi, however, PvFER2, PvHERK1C, and PvHERK1A were downregulated in inoculated roots compared to the controls, as was PvHERK1C at 14 dpi (Figure 6D–F). A third expression pattern was displayed by PvTHE2; transcripts of this gene showed increased accumulation in inoculated roots at 7 and 14 dpi relative to the controls but at 5 and 21 dpi, levels of transcript accumulation were similar to the controls (green box, Figure 6G). Finally, PvMEDOS1C showed fine-tuned changes in expression; relative to the controls, transcript accumulation for this gene was decreased at 5 and 21 dpi, increased at 7 dpi, and unchanged at 14 dpi (brown box, Figure 6H).

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR expression analysis of eight P. vulgaris CrRLK1L genes. Relative expression profiles of eight CrRLK1L genes from P. vulgaris roots inoculated or not with R. tropici. Genes were classified into four groups according to their expression; the blue box indicates downregulated genes at the early and late time points: PvFER1 (A), PvMEDOS1A (B), and PvCAD3 (C); the purple box shows genes whose expression is upregulated at the early time points assessed, but downregulated later on: PvFER2 (D), PvHERK1A (E), and PvHERK1C (F); the yellow box indicates the expression of PvTHE2 (G), which was upregulated at the early and late time points; and the brown box displays PvMEDOS1C (H), showing variable expression at the different time points evaluated. The transcript accumulation of the selected genes was assessed by RT-qPCR and normalized according to elongation factor 1α (ef1α) gene expression. Blue bars represent inoculated roots, whereas gray bars indicate the expression levels in non-inoculated roots. The error bars represent standard deviation of the mean (n = 6). A Student’s t-test was performed to evaluate significant differences, * represents p ≤ 0.05, ** represent p ≤ 0.01, ns represents non-significant difference.

These data indicate that the eight genes analyzed here are indeed differentially expressed in common bean roots at different stages of the nodulation process and probably perform different functions throughout the symbiotic process.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Features of CrRLK1L Genes

The RLK subfamily CrRLK1L has emerged as an important signaling component of numerous biological processes, including development, immune responses, and fertilization, among others. Previous studies have analyzed the phylogeny of CrRLK1L genes in A. thaliana, rice (O. sativa), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), and pear (Pyrus bretschneideri), as well as their expression under different conditions [68,69,70]. However, it is important to extend these studies to other agro-ecologically important crops, such as legumes, which have the ability to fix nitrogen in association with the soil bacteria rhizobia. Furthermore, a comprehensive phylogenetic study of the CrRLK1L subfamily in a larger number of plant species will yield new information about the functions of these proteins and their evolutionary paths since their appearance in the plant kingdom. The usefulness of this bioinformatic approach is evident in the current study, in which we were able to analyze the CrRLK1L subfamily in model legumes and common bean, using different “in silico” approaches, and thereby elucidate its possible functions in the legume-rhizobia mutualistic interaction.

We identified 1050 CrRLK1L proteins from the 57 embryophytes included in this analysis, which fell into 11 phylogenetically distinct clades (Figure 1A, Figure S1, Table S2). Chlorophytes lack this plant-specific RLK subfamily, indicating that it arose during the transition from chlorophytes to embryophytes, which probably occurred about 500 million years ago (mya) [71]. A feature that differentiates embryophytes from other plants is their sexual reproduction [71,72] and, since some CrRLK1Ls are key regulators of fertilization [4,16,30,31,33,36], this may link the emergence of the CrRLK1L subfamily with the advent of embryophytes. We found that bryophyte CrRLK1Ls cluster together in a unique clade (TINIA), whereas the land plant proteins are distributed among the remaining ten clades (Figure 1A, Figure S1, Table S2). The number of CrRLK1Ls in these mosses varies from one to seven, revealing the first duplication events of the CrRLK1L lineage. Monocots and eudicots diverged around 150 mya, and have evolved along different evolutionary paths [73]. The subsequent eudicot radiation, dated around 100 mya, has been associated with polyploidization events [74]. Interestingly, there are more CrRLK1L proteins in eudicots than in monocots, demonstrating the different evolutionary fates of the genes of this subfamily in monocots and eudicots. Some eudicots have particularly large numbers of these proteins compared to other eudicots (Figure 1A–B, Table S1). This increase in the number of CrRLK1Ls could be associated with the appearance of the MEDOS clade (present in all eudicots but in only a few monocots) and with subsequent expansion of the MEDOS clade in eudicots.

Our phylogenetic analysis of CrRLK1Ls from four legumes, A. thaliana, and P. patens, revealed 155 genes distributed in 11 clades (Figure S2A). As expected, the MEDOS clade had the most members. We observed that the proteins in this clade are clustered on one chromosome in A. thaliana and L. japonicus, while in P. vulgaris, G. max, and M. truncatula, these genes form two clusters (Figure S3). Some reports indicate that in plants the expansion of gene subfamilies mainly occurred through dispersed, tandem, and whole-genome duplications [75,76,77,78,79,80]. In pear, most CrRLK1L genes arose by whole-genome duplication and some by dispersed gene duplications [70]. The tandem duplications we observed suggest that, in the analyzed legumes and in plants with a high number of CrRLK1L genes, the MEDOS genes arose from tandem duplications, whereas the other CrRLK1L genes probably arose from whole-genome or segmental duplications.

The exon-intron structure of genes has been associated with gene function, and it affects RNA splicing, RNA stability, and chromatin organization [81,82,83]. Exon-intron patterns have been used to reveal time evolution, constant variation, and their co-variations [84]. Our comparative analysis of the exon–intron distribution in CrRLK1L genes revealed that, compared to A. thaliana, legumes have more CrRLK1L genes with introns and more introns in each gene (Figure 4). Nevertheless, the expression patterns of the legume CrRLK1L genes were similar to those of the corresponding orthologs in A. thaliana (Figure 5). In pear, it has been proposed that the CrRLK1L genes have lost introns, but their expression patterns are similar to those of A. thaliana and rice genes [85]. Our observations suggest that the increase in the number of introns is associated with duplication and evolutionary events, but these have little or no effect on gene function and expression.

Analysis of the synteny of the CrRLK1L genes revealed homology between some gene pairs in the plants analyzed. In P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and A. thaliana, four, one, and two syntenic gene pairs were identified, respectively; each gene observed was syntenic with only one additional gene (Figure S4). By contrast, 21 syntenic gene pairs were identified in G. max, and some genes have synteny with more than one other gene (Figure S4). The higher number of syntenic genes in G. max is probably because of the polyploidization event that occurred in this legume [86]. Compared to the number of syntenic CrRLK1L genes we observed between P. vulgaris and G. max, there were fewer between either of these species and L. japonicus, and even less between P. vulgaris and A. thaliana (Figure 3). There is a clear correlation between the degree of synteny and the time of divergence between species [74,76]. The degree of synteny also depends on the evolution of the genome; in angiosperms, whole-genome duplication and subsequent gene loss have driven plant evolution and have also reduced collinearity across species [77,87]. Our data are consistent with an early divergence between P. vulgaris and G. max, compared to L. japonicus, and an even longer divergence time between P. vulgaris and A. thaliana.

The characteristics of a protein are important for its activity and correspond with taxonomy, environmental adaptation, subcellular localization, and genome size [85,88]. From this perspective, the contrast between the characteristics of CrRLK1Ls from legumes versus A. thaliana denotes greater variability in the legume sequences and correlates with larger genomes (Table 2). A protein’s iP reflects its amino acid composition and conformation and determines its activity [89]; the wider iP ranges and longer sequences of the legume CrRLK1Ls could reflect specialization of some of these proteins for different tissues or processes, possibly giving these plants better adaptability to environmental changes. In the five plant species studied here, we observed a high conservation of overrepresented motifs in all of the CrRLK1Ls (Figure 2). The conservation of these motifs, which are located in the malectin and kinase domains characteristic of this subfamily, indicates their importance for protein activity.

4.2. Differences and Similarities in the Expression of CrRLK1L Genes in Legumes and in A. thaliana

Previous studies in A. thaliana have reported that CrRLK1L genes participate in a variety of processes, such as development, cell communication, and plant-microbe interactions (Table 1), and that the functions of these genes correspond with their expression profiles (Figure 5E). A previous study comparing CrRLK1L gene expression in pear and A. thaliana reported that the expression profiles of some genes are conserved between these species; however, the expression of many other genes was lost or altered in pear compared to A. thaliana [70]. We performed a comparative in silico analysis of CrRLK1L gene expression profiles in four legumes and A. thaliana and observed that the expression patterns of most of the genes are conserved. FER, HERK, THE, CRV, and MEDOS showed similar expression profiles in the five species examined; these genes are expressed in almost all tissues. In A. thaliana, ANX, BUPS, and CAP are pollen-specific genes. These genes are not expressed at detectable levels in P. vulgaris or L. japonicus, at least in the tissues included in the databases (Figure 5). However, since there is no data available for expression of these genes in pollen or pollen tubes, we propose that these genes could also be pollen-specific in these legumes, as they are in A. thaliana. The expression profiles of some of the legume CAD genes differed by two to ten-fold from those of the AtCAD genes in some tissues, suggesting additional functions for these genes in legumes.

Legumes are characterized by the ability to form nodules that house endosymbiotic rhizobia. This relationship generates a driving force between the two symbionts that leads them to co-evolve [90,91]. It has been reported that plant lipochitooligosaccharide receptors acquired symbiotic functions before gene duplication [92]. In the four legumes analyzed here, some CrRLK1L genes showed transcript accumulation in nodules, suggesting that these genes have been recruited to the symbiotic process, in addition to any other roles they may have. We identified nine genes that were expressed in nodules in P. vulgaris, nine in L. japonicus, ten in G. max, and nine in M. truncatula. Among those genes, FER1 is expressed in nodules of all four legumes, (Figure 5, Figure S5), five other nodule-expressed genes were shared between three of the four legumes, seven shared by different pairs of legumes, and four genes were expressed in nodules of only one of the legumes (Figure 5, Figure S5). These data may suggest that some CrRLK1L genes participate in the symbiotic process. Nonetheless, further functional analyses are needed to test this hypothesis.

4.3. Putative Roles of CrRLK1L Genes during Nodulation

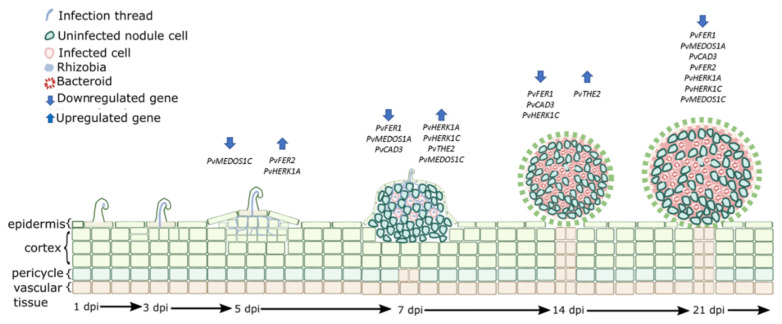

We examined the expression profiles of eight CrRLK1L genes in P. vulgaris roots inoculated with R. tropici and found that these genes were differentially expressed at different stages of nodule development. Figure 7 provides a schematic summary of the nodulation process in P. vulgaris and the steps in which the eight genes presumably participate. At 5 dpi, the nodule primordia begin to emerge from the root epidermis, and the infection thread, filled with bacteria, penetrates the outer cortex of the root and branches [93,94,95,96,97]; at this point, PvMEDOS1C was downregulated in the inoculated roots relative to the control, whereas PvFER2 and PvHERK1A were upregulated (Figure 7). By 7 dpi, many nodules have already emerged from the root epidermis, and some nodule primordia cells contain bacteria that have been released from the infection threads [95,96,97,98,99]; at this time, four genes (PvHERK1A, PvHERK1C, PvTHE2, and PvMEDOS1C) showed high expression, whereas three others (PvFER1, PvMEDOS1A, and PvCAD3) exhibited low expression in inoculated roots relative to the control (Figure 7). Some CrRLK1Ls have been reported to be important regulators of cell expansion, cell wall maintenance, and membrane integrity during cell growth [3,32,100,101,102]. The P. vulgaris CrRLK1L genes that are induced at 5 and 7 dpi could be supporting similar functions, since at these nodulation stages, there are high rates of cell division and expansion [97,103,104,105,106,107]. Likewise, internalization of the bacteria depends on growth and branching of the infection thread through the root cortex and subsequent release of the bacteria into the cells of the nodule primordia [97,98,99]. Some CrRLK1L genes have been reported to be regulators of immune responses [9,11,12,20,108], indicating that downregulation of some CrRLK1L genes at this stage of nodulation might inhibit pathogen responses during infection.

Figure 7.

Putative roles of the eight CrRLK1L genes evaluated during nodule organogenesis in common bean. Graphic representation of the proposed roles of the eight CrRLK1L genes of common bean, based on the RT-qPCR data obtained in this study. Different stages corresponding to days post-inoculation (dpi) are observed. At the early stages, the bacteria and the root establish a molecular dialogue, which promotes curling of the root hair where the bacteria are enclosed in an infection chamber (not shown). One to three days before the bacteria become trapped, an infection thread (IT) is formed, which advances through the infected root hair cell, reaching the outer cortex of the root. Concurrently, cortex cells de-differentiate and divide. By 5 dpi, dividing cells in the outer cortex generate a nodule primordium, whereas the IT branches toward the primordium. By 1 nitrogen fixation rates.

At 14 dpi, the bacteria within the infected cells differentiate into bacteroids and most of the nodules are matured, initiating nitrogen fixation [93,95,96,109,110,111]. At this stage, three genes, PvFER1, PvCAD3, and PvHERK1C, were downregulated and PvTHE2 was upregulated in inoculated roots relative to non-inoculated ones (Figure 7). The downregulated genes could be associated with avoidance of immune responses, as earlier in the nodulation process. In addition, the downregulated genes could be involved in regulating nitrogen flow, considering that, in A. thaliana, FER has been reported to be a growth regulator that responds to the C/N ratio [14]. Downregulation of some CrRLK1Ls may be necessary to promote nitrogen fixation. The upregulation of PvTHE2 suggests that this gene may be associated with other functions during this stage, such as nodule development. At 21 dpi, common bean nodules are fully developed and display high rates of nitrogen fixation [93,96,110,111]. PvFER1, PvFER2, PvHERK1A, PvHERK1C, PvMEDOS1A, PvMEDOS1C, and PvCAD3 were downregulated at 21 dpi (Figure 7). The downregulation of most of the CrRLK1L genes could be related to the end of nodule development and to deactivation of immune responses to maintain symbiosis and nitrogen fixation at the highest levels.

ROS are important signaling molecules that participate in nodule organogenesis processes associated with CrRLK1Ls. In plant cells, ROS are mainly produced through the activity of respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs in plants), which are called NADPH oxidases in mammals [112]. RBOH-dependent ROS production has been described as a conserved mechanism in CrRLK1L activity; FER, ANX1, and ANX2 promote phosphorylation, and thereby activation, of RBOH, inducing ROS-mediated polar growth in pollen tubes and root hairs in A. thaliana [10,32]. In P. vulgaris and M. truncatula, ROS signaling is essential for initiating root hair cell responses to the presence of rhizobia. Impairment of ROS production through downregulation of Rbohs in these species inhibits the progression of infection thread growth in P. vulgaris (PvRbohA and PvRbohB) and swelling of root hair tips in M. truncatula (MtRbohB and MtRbohE) [113,114,115]. In addition, previous studies have revealed Rboh promoter activity associated with cell division in the cortex and vascular bundles of nodules, suggesting a possible role of these oxidases in nodule development [114,115,116,117]. Similarly, Rboh genes are differentially expressed during nodulation in P. vulgaris, L. japonicus, and M. truncatula [114,115,117,118], as we observed for eight nodule-expressed CrRLK1L genes in common bean. Altogether, these data suggest that the CrRLK1L genes may be participating in the nodulation process through regulation of ROS signaling at specific stages of nodule organogenesis.

Phytohormones also appear to have roles in nodulation. For instance, studies in several legumes have reported that abscisic acid (ABA) is a negative regulator of nodulation [119,120] but that it also has some positive effects on the growth and functioning of nodules [121,122]. In pea (Pisum sativum) and soybean (G. max), brassinosteroid (BR) inhibits nodulation in some studies [123,124], whereas in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) and P. vulgaris, some studies show positive effects of BR on nodulation [125,126]. Jasmonic acid (JA) has both positive and negative effects on nodulation, depending on the legume species and the stage of nodule development at which it is applied [119,127,128,129]. Ethylene has mainly been associated with negative regulation of nodulation [130,131]. RALF peptide hormones have been reported to be negative regulators of infection and nodule organogenesis in M. truncatula [45]. Some CrRLK1Ls are known to be RALF receptors [8,39,40,101]. In A. thaliana, the expression of FER, THE, and HERK is induced by BRs [4] and FER is a hormone response modulator, fine-tuning ethylene and BR signaling during hypocotyl growth [5] and suppressing ABA and JA signaling [6,9]. In the current study, we found that two FER genes, two HER genes, and one THE gene were differentially expressed at different stages of nodulation in common bean. These results, along with the previously described roles for these genes in regulating hormone signaling, allow us to speculate that these genes may participate in nodulation through the regulation of hormone signaling at several stages of nodule organogenesis. Nonetheless, experimental evidence is needed to test this hypothesis.

In this work, we examined eight differentially expressed CrRLK1L genes at different stages of nodulation in common bean. Based on our results, we postulate that these proteins are regulators in this process. Forthcoming reverse genetics experiments in common bean will expand our knowledge of the particular roles of these CrRLK1L genes in nodulation. Our analysis of previously published transcriptomic data [60,61,63,64] demonstrated that related CrRLK1L genes are expressed in nodules of other legumes. Based on the phylogenetic, syntenic, and expression profiling analyses reported here, we predict that CrRLK1L subfamily homologs in other legumes may have a conserved role in nodulation, as these genes presumably do in common bean.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we identified 1050 CrRLK1L proteins in 57 plant species, clustered into 11 clades, one of them specific to moss and clubmoss proteins. This receptor subfamily probably appeared with the emergence of land plants, since no homologous proteins were detected in chlorophytes. In silico analysis in legumes and A. thaliana revealed that these receptors have expanded mostly by whole-genome and isolated duplication, and in the case of the MEDOS clade, by tandem duplication. Moreover, this analysis revealed high conservation of gene and protein structure and high similarities in expression profiles, suggesting analogous functions. Remarkably, RT-qPCR quantification of transcript levels in P. vulgaris roots inoculated with R. tropici revealed that some CrRLK1L genes could have different roles at different stages of the nodulation process. Considering the genomic similarities observed, we speculate that these roles in nodule organogenesis could be conserved in other legumes.

Supplementary Materials