Abstract

Background

Many differences exist in postgraduate surgical training programmes worldwide. The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the training requirements in general surgery across 23 different countries.

Methods

A collaborator affiliated with each country collected data from the country's official training body website, where possible. The information collected included: management, teaching, academic and operative competencies, mandatory courses, years of postgraduate training (inclusive of intern years), working‐hours regulations, selection process into training and formal examination.

Results

Countries included were Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, India, Ireland, Italy, Kuwait, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, USA and Zambia. Frameworks for defining the outcomes of surgical training have been defined nationally in some countries, with some similarities to those in the UK and Ireland. However, some training programmes remain heterogeneous with regional variation, including those in many European countries. Some countries outline minimum operative case requirement (range 60–1600), mandatory courses, or operative, academic or management competencies. The length of postgraduate training ranges from 4 to 10 years. The maximum hours worked per week ranges from 38 to 88 h, but with no limit in some countries.

Conclusion

Countries have specific and often differing requirements of their medical profession. Equivalence in training is granted on political agreements, not healthcare need or competencies acquired during training.

Many differences exist worldwide in postgraduate surgical training programmes. Countries have specific and often differing requirements of their medical profession. Equivalence in training is granted on political agreements, not healthcare needs or competencies acquired during training.

Wide variation between countries

Antecedentes

Existen muchas diferencias entre los programas de formación quirúrgica de posgrado del mundo. El objetivo de este estudio fue proporcionar una visión general de los requisitos formativos en cirugía general en 23 países diferentes.

Métodos

En cada uno de los países participantes, un colaborador recopiló datos de la página web del organismo oficial encargado de la formación, si era posible. La información incluyó: gestión, formación, competencias académicas y operatorias, cursos obligatorios, años de formación de postgrado (que incluía el período de internado), regulaciones sobre las horas de trabajo, proceso de selección para la formación y existencia de un examen final.

Resultados

Se incluyeron los datos de Australia, Bélgica, Canadá, Colombia, Dinamarca, Alemania, Grecia, Guatemala, India, Irlanda, Italia, Kuwait, Países Bajos, Nueva Zelanda, Rusia, Arabia Saudita, Sudáfrica, Corea del Sur, Suecia, Suiza, Reino Unido, Estados Unidos de América y Zambia. En algunos países existen los marcos normativos para definir los resultados del programa de formación, con ciertas semejanzas a los del Reino Unido e Irlanda. Sin embargo, algunos programas de formación, incluso en muchos países europeos, son muy heterogéneos con variaciones regionales. Pocos países describen el número mínimo de procedimientos quirúrgicos (rango 60 a 1.600), los cursos obligatorios o competencias quirúrgicas, académicos o de gestión exigidos. La duración de la formación postgraduada osciló de los 4 a los 10 años. El número de horas trabajadas máximas por semana oscilaron entre 38 y 88, sin límite en algunos países.

Conclusión

Cada país tiene unos requisitos específicos, a menudo diferentes, para la formación de sus médicos. La convalidación se otorga por acuerdos políticos, más que por las necesidades médicas o por las competencias adquiridas durante la formación.

Introduction

The specialty of general surgery within the UK encompasses emergency abdominal and trauma surgery, oesphagogastric and hepatopancreatobiliary surgery, colorectal surgery, endocrine surgery, transplant surgery, breast surgery, general paediatric surgery, hernia surgery and, until 2013, vascular surgery1. General surgical training in the UK is therefore tailored to allow exposure of these specialist areas in order to attain the required competencies to complete postgraduate training and become an independent practitioner. There is also a requirement to demonstrate competency in research, teaching and management skills.

There are many recognized differences in surgical training worldwide; however, equivalence is often granted between many of them. Individual countries may have differing priorities for the care of their patient population encompassed within general surgery. This may result in differing requirements in terms of operative competence, academic output, and teaching and management skills, as well as the length of training, to complete postgraduate surgical training and become an independent practitioner in that country.

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the training requirements for general surgery across 23 different countries.

Methods

Collaborators were invited to participate in the study; all had clinical experience of working in each included country. Where publicly accessible, data relating to training requirements were gathered from the website of countries' official training regulators, and then validated by the collaborator.

Data collected were chosen based on various domains that are assessed in the surgical training programme in the UK and Ireland, where the Joint Curriculum on Surgical Training (JCST) is responsible for curriculum development and implementation for general surgical trainees. For an individual trainee to be awarded a Certificate of Completion of Training within their chosen surgical specialty, they must demonstrate competence in line with the guidance provided by JCST on behalf of the Specialist Advisory Committee2. This guidance outlines the necessary criteria across a number of domains: operative competence (overall number of operative cases, indicative number of operations (related to general surgery and the trainee's specialist interest), procedure‐based assessments); assessment of clinical experience (case‐based discussion); research competence; management competence; medical education and training competence; and mandatory courses.

These domains of operative, research, teaching and management competencies, alongside mandatory courses, were used as criteria to collect data regarding training requirements in general surgery from other countries. Data were also obtained on the length of postgraduate training, including any internship years, and the average/maximum hours worked per week, as well as the selection process into surgical training and formal examination during surgical training.

Owing to the nature of the study, a descriptive review was performed. Ethical dimensions of this evaluation study were considered, and no concerns were identified.

Results

Data were obtained from 23 countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, India, Ireland, Italy, Kuwait, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, USA and Zambia (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Countries included in the study

Frameworks for defining the outcomes of surgical training have been defined nationally in some countries, such as the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada CanMEDS (Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists) framework3 and the Accreditation Council for General Medical Education (ACGME) framework in the USA4. Some frameworks are universal across several countries. For example, Australia and New Zealand share a framework, Surgical Education and Training Programme, under the responsibility of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons5, and Zambia shares a framework with several other countries in Africa under the responsibility of the College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa6. Details of the training body websites, where available, are detailed in Table S1 (supporting information).

Years of training

The number of years in postgraduate training varies greatly, from 4 years in Colombia to 10 years in the UK. Eleven of the 23 countries require trainees to complete an internship before starting surgical training; this varies from 1 to 2 years (Fig. 2). In the UK, trainees must complete two foundation ‘generic’ years (covering both medical and surgical, as well as community‐based, rotations) and achieve set competencies; this is followed by entry into specialist training (decoupled into 2 years at core level and 6 years at higher level). Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Sweden also have a 2‐year internship period before entering surgical training. In the USA, trainees are required to have five progressive years of residency after graduation; traditionally they were required to complete a separate 1‐year internship, but this is now often combined in the residency. Canadian surgical residency training includes 2 years of foundation surgical training (blocks as a junior resident in general surgery, critical care and initial trauma management). In Zambia, trainees are expected to have a minimum of 18 months' clinical experience before applying for specialty training, but there is no upper limit. Trainees in Denmark, India, Kuwait and South Korea also complete an intern year before applying for specialty training. In many countries, such as the Netherlands, it is commonplace for doctors to spend time working in non‐training posts and to do research before becoming successful at appointment for surgical training. It is also commonplace in Saudi Arabia for those who have completed training to spend 3 years as a senior registrar plus an overseas fellowship before taking up a consultant post.

Figure 2.

Length of postgraduate training in the 23 countries studied

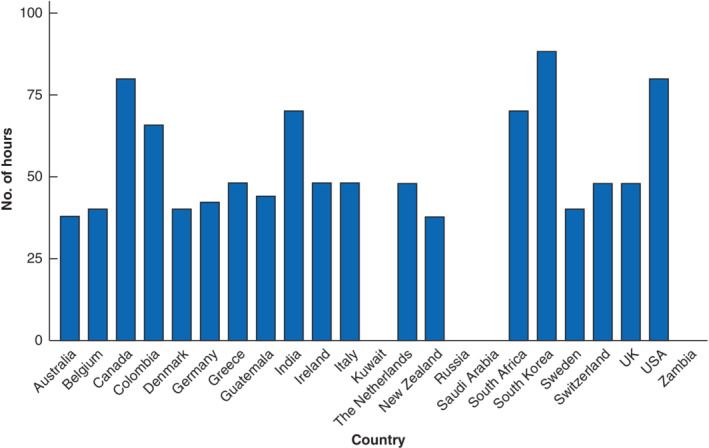

Maximum hours worked per week

The maximum hours worked per week are shown in Fig. 3. In countries in the European Union, the European Working Time Directive reduces the working week to an average of 48 h, and there are further regulations relating to break periods and holiday allowances. Trainees are required to have 11 h of rest daily, and have a right to 1 day off each week. However, the working hours of Swedish residents must not exceed an average of 40 per week as defined by the Swedish Working Hours Act, although if overtime is necessary a maximum of 48 working hours is permitted. There must be a minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive hours in every 24 h. There is extra protection in the case of night work, where average working hours must not exceed 8 h per 24‐h period.

Figure 3.

National working hours restrictions in the countries studied

In the USA, the ACGME has limited the number of working hours to 80 h weekly, overnight working frequency to no more than one in three nights, a maximum of 30 h for straight shifts, and at least 10 h off between shifts. Although these limits are voluntary, adherence has been mandated for accreditation. Canadian residents also work an average of 80 h per week. The Canadian resident duty hours revolve around the negotiated contract between residents' associations and the provincial jurisdictions in which they train. Since 2018, South Korea has legislated to limit working hours to 80 h per week (extended to 88 h per week on the premise that the additional hours are education time). Australia and New Zealand limit working to 38 h per week. In contrast, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Zambia have no regulations on working hours. It should be noted that collaborators across many countries commented that trainees often work over and above their contracted maximum hours, although this is difficult to quantify or verify.

Operative competencies

All countries studied require a logbook record of operative procedures performed to be kept to evidence experience. The requirements of the logbook in some countries are determined by individual schools or regions rather than national guidelines. For example, in Italy, Germany and Russia, where training is very heterogeneous across the country, each separate school board defines theoretical and practical activities that residents have to complete and the operative requirements that each resident has to fulfil according to the teaching programme.

National minimum numbers of operative procedures are detailed in only ten of the 23 countries (Fig. 4; Table S2 , supporting information). It should be noted that both the types of operation included in the minimum numbers required and whether the minimum number of operations includes observed or assisted cases are variable across countries. Where specified, the operative competencies required and the overall minimum number of cases for completion of training vary greatly across countries, ranging from only 60 in South Korea to 1600 cases in the UK and Ireland. Six of the countries with minimum overall operative cases also detail minimum numbers for specific operations: Denmark, Ireland, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK (Table S2 , supporting information). Kuwait lists minimum numbers of operative cases for a range of specific operations, but not an overall minimum number. Seven countries (Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Ireland, the Netherlands, South Africa and UK) specify the requirement of operative competencies for a defined list of operations. Australia and New Zealand require 80 major cases.

Figure 4.

Minimum number of surgical procedures required across countries, where specified

It is common practice in many countries that further training time after the completion of training, in the form of fellowships for example, is a prerequisite for the practice of some specialist interests, such as surgical oncology, as in South Korea and Saudi Arabia.

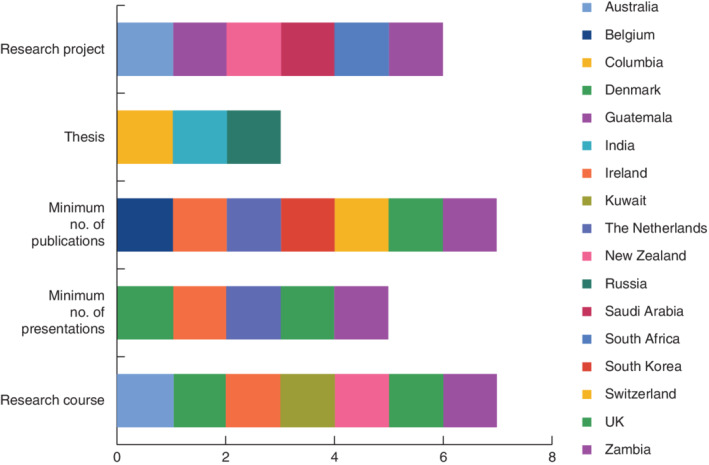

Research competencies

Minimum academic and research competencies are specified by 17 of the 23 countries (Fig. 5; Table S3 , supporting information). The competencies vary greatly. Some countries require trainees to complete a research proposal, project or thesis during training (Australia, Colombia, Guatemala, India, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa and Zambia). Other countries state that a minimum of one peer‐reviewed publication is required (Belgium, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Zambia), whereas the UK and Ireland are the only countries that require more than one publication. A few countries state multiple evidence that can be used to demonstrate research competence, such as Australia and New Zealand stating that a presentation, publication, dissertation or full‐time research is applicable, and Switzerland describing either a publication or thesis. In Belgium, alongside one peer‐reviewed publication, trainees are required to demonstrate either a second publication or presentation at a scientific congress. Seven countries (Australia, Denmark, Ireland, Kuwait, New Zealand, UK and Zambia) require mandatory attendance on a research course.

Figure 5.

Research competencies required during training in the countries studied

Management competencies

Management competencies are set out by 15 of the 23 countries (Table S4 , supporting information). These commonly involve the understanding of healthcare management through attendance on a course during training, and the ongoing managerial positions and involvement within teams and organizations. For example, in the UK and Ireland trainees are required to have completed a course on health service management during training and to provide evidence of having taken part in a management‐related activity such as rota administration, trainee representative or membership of a working party. Six countries (Belgium, Denmark, Guatemala, Ireland, UK and Zambia) require satisfactory completion of specific management courses as evidence.

The guidelines for Australia, Canada, Kuwait, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Switzerland, South Africa and the USA state that management competencies are a prerequisite, but do not outline specific details as to how these are assessed for satisfactory completion of training. The common aim of all these listed requirements is to improve the delivery of healthcare. Evidence of leadership skills and the ability to run a team effectively and work with other healthcare professionals is an important factor. In some countries with private healthcare systems it is also expected that doctors have an understanding of the finances involved. For example, in Switzerland, trainees can be required to bill patients on behalf of the hospital during clinics, and therefore must understand the costs of services provided to their patients.

Mandatory courses

Seven countries (Canada, Colombia, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, India and Switzerland) have no defined specific courses that are required for the completion of training. A trauma management course and basic surgical skills are required by ten and 11 countries respectively (Fig. 6; Table S5 , supporting information).

Figure 6.

Mandatory courses required during training in the countries studied

Selection into surgical training

Eight countries (Australia, Guatemala, Italy, Ireland, New Zealand, UK, USA and Zambia) have a national selection process into surgical training (Table 1). There is variation between all countries in the use of entrance examinations, applications and/or interviews.

Table 1.

Selection process into surgical training for the 23 studied countries

| Country | Selection process for surgical training |

|---|---|

| Australia | National system |

| Referee report, interview scores and review of CV | |

| Belgium | Direct application to a university. It is usual to have an examination and interview as part of the selection process |

| Canada | Direct application to individual centres after completion of the Royal College Surgical Foundations examination and curriculum |

| Colombia | Usually competitive entrance test, interview and psychotechnics test, but can vary depending on the institution |

| Denmark | Regional interviews |

| Germany | Direct application to a hospital |

| Greece | Direct application to a region |

| Guatemala | Standardized postgraduate entry examination, interview scores and review of curriculum |

| Grades are ranked and slots assigned to each hospital | |

| India | Entrance examination and interview‐based entry into MCh programmes (national level with or without a different examination for each institution) |

| Ireland | National application and interview |

| Ranking to match with candidate's choice of region for training | |

| Italy | National examination; score determines choice of one of three desired schools |

| Kuwait | Interview with programme directors |

| New Zealand | National system |

| Referee report, interview scores and review of CV | |

| The Netherlands | Interview appointed per region. Can apply to two regions per year |

| Russia | Direct application to regions |

| Saudi Arabia | Interview with programme directors |

| South Africa | Expected to have passed ‘primary’ College of Surgeons examination before applying. Applications and interviews take place at individual hospitals |

| South Korea | Direct application to a hospital. Selection process determined by the hospital |

| Internship national examination used for selection processes | |

| Sweden | Direct application to a hospital, usually an interview‐based process |

| Switzerland | Direct application to university centres |

| UK | National application and interview |

| Ranking to match with candidate's choice of region for training | |

| USA | Must have completed United States Medical Licensing Examination |

| National application and interview | |

| Ranked through the National Resident Matching Program, which ultimately matches applicants with a programme | |

| Zambia | National application |

CV, curriculum vitae; MCh, Master of Surgery.

Examination during surgical training

In most countries trainees are required to pass a national examination before the completion of training (Table 2). Four countries (Colombia, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) do not have a formal examination during surgical training, and formal assessment is undertaken in the form of continual clinical assessments only.

Table 2.

Formal examination for each of the 23 studied countries

| Country | Examination |

|---|---|

| Australia | Fellowship of the RACS |

| Belgium | Two formal examinations during surgical training |

| Canada | Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons certification examination in general surgery |

| Colombia | No formal examination |

| Denmark | No formal examination; continuous assessment only |

| Germany | Final specialist examination |

| Greece | Final specialty examination |

| Guatemala | Evaluation test designed by each hospital |

| India | MCh (MCI) or DNB (NBE) qualification involving theory papers and clinical and oral examinations |

| Ireland | MRCS examination in core surgical training and FRCS examination towards the end of surgical training |

| Italy | Oral examination every year and a final examination with dissertation at the end of training |

| Kuwait | Part I examination of the Kuwait Surgical Board at completion of the surgical core programme, and Part II final examination at completion of higher surgical training |

| New Zealand | Fellowship of the RACS |

| The Netherlands | No formal examination; continuous assessment only |

| Russia | Final specialist viva examination |

| Saudi Arabia | Annual end‐of‐year examination |

| Part I: Saudi Board examination ‘principles in general surgery’ | |

| Part II: final general surgery Saudi Board examination | |

| South Africa | FCS(SA) examination (primary, intermediate and final) |

| South Korea | Specialty examination at end of residency and a subspecialty examination at end of fellowship, run by individual subspecialty associations; neither is mandatory |

| Sweden | No formal examination; continuous assessment only |

| Switzerland | Swiss General Surgery Board Certification |

| UK | MRCS examination in core surgical training and FRCS examination towards the end of surgical training |

| USA | American Board of Surgery In‐Training Examination (ABSITE®), taken yearly during training |

| General Surgery Board Certification to complete residency programme | |

| Zambia | University of Zambia examination |

| COSECSA examination to allow the individual to work outside Zambia, in other regions of Africa |

RACS, Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; MCh, Master of Surgery; MCI, Medical Council of India; DNB, Diplomate of National Board; NBE, National Board of Examinations; MRCS, Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons; FRCS, Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons; FCS(SA), Fellowship of the College of Surgeons of South Africa; COSECSA, College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa.

Discussion

The competence of surgeons can be defined as the level of skill, knowledge and experience necessary to manage surgical conditions and perform surgical procedures safely. In many countries included in this study, there are no universal national guidelines published for quality assurance of training schemes, and thus the resultant end‐product of the trainee. In many cases, different institutions within countries have individual regulations, and therefore different requirements to become an independent practitioner. For example, despite automatic mutual recognition in the European Union, there is great variation within the spectrum of competences and education in general surgery across Europe, with many requirements being dependent on individual institutions or local demand. An example of this heterogeneity is shown by the German regulations, where the medical boards of each federal state have their own specialty regulations. The model for these regulations is provided by the German Medical Board. Each medical board in every federal state then works on its own regulations based on this model.

The aim of any surgical training programme must be to produce competent, safe, independent surgeons. Traditionally, the focus had been on technical skills, and these have been used to define outcomes that are assessed at a local level rather than being compared with defined national or international standards. Some countries have developed frameworks for defining the outcomes of surgical training. These frameworks broaden the focus of surgical training, and also establish a quality assurance process.

Although technical ability is an important prerequisite for a successful outcome of training, other qualities such research understanding and contribution, personality and communication skills, teaching and management skills, and a commitment to practise are important requirements. Importantly, several countries have recognized the necessity to ensure these other qualities are assessed throughout surgical training.

This paper highlights that, although equivalence is granted between countries, for example within the European Union, the skill mix and competence of the surgeon is likely to be hugely variable, dependent on the country in which surgical training was undertaken. This has huge implications for the movement of professionals between countries.

Clearly, a ‘one size fits all’ approach, with regard to mandatory training programme requirements that the trainee should demonstrate is not appropriate, as the needs for surgical provision will vary greatly dependent on the local population. However, there are many competencies that should be universal across all healthcare professionals, such as a minimum competency level in research, teaching and management. All clinicians have a duty to strive towards the practice of evidence‐based medicine and to appraise research critically, as well as to train the future generation of doctors, and to manage and lead effectively the team within which they work. Nonetheless, the remodelling of training pathways to mimic those of other countries should be done with caution. The ‘dumbing down’ of a country's training requirements, based on the comparison with other countries with a view to financial savings, should be avoided at all costs, and all countries should be striving to produce the highest quality of surgeons with the skill mix needed to serve their local population.

A meta‐analysis7, published in 2017, considered the global operative experience at completion of surgical training in general surgery. This included 17 studies, with operative experience data included from the USA, UK, the Netherlands, Spain and Thailand. This described the mean operative numbers of trainees on completion of a surgical training programme, rather than the nationally defined minimum requirements derived from guidance. Data in the majority of the included studies were not contemporaneous, spanning back as far as 1992. Other surgical specialties have published similar findings for global variation in training programme requirements, mainly orthopaedics within Europe8 and plastic surgery worldwide9. They both drew similar conclusions to those in the present study, with wide variation in the requirements of completion of training within orthopaedics and plastic surgery8, 9.

This study has a number of potential limitations. The data included were obtained, where publicly accessible, from national published guidelines, but this was possible only for countries where English is the official language, and therefore applied to only a few of the countries studied. Collaborators, with experience of clinical working within the country, were otherwise asked to submit data relating to their countries' training pathway requirements, and the accuracy of the data is therefore reliant on interpretation and translation of the guidance from individual collaborators. It was not possible to collect data relating to all regional programme variations within some countries, such as Italy or Germany; thus, although there are no published overall minimum requirements for many of the domains studied, there may in fact be a minimum requirement if all the regional set levels were to be compared.

This study included data from only 23 countries. Collaborators from other countries were contacted to participate, but they either failed to respond or did not provide information relating to some domains, and the country was thus excluded from the study. Therefore conclusions cannot be drawn about general surgical training around the whole world, only comparisons made between the 23 included countries.

In this study analysing the differences in general surgery training programme requirements worldwide, using contemporaneous published guidance on national training programmes, there was great variability in the competence and skill set seen between countries. This variation should be recognized in relation to the movement of healthcare professionals and when redesigning training pathways.

Collaborators

Global Surgical Training Requirements Project Collaborators: M. L. Aguilera, H. Ahrend, A. Al Qallaf, J. Ansell, A. Beamish, B. Borraez‐Segura, F. Di Candido, D. Chan, T. Govender, F. Grass, A. K. Gupta, Y. Dae Han, K. K. Jensen, M. Kusters, K. Wing Lam, M. Machila, C. Marquardt, I. Moore, S. Ovaere, H. Park, C. Premaratne, I. Sarantitis, H. Sethi, R. Singh, J. Yonkus.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1 Training authority website for each studied country

Table S2 Minimum operative requirements across countries

Table S3 Academic competencies required by each country

Table S4 Management competencies required by each country

Table S5 Mandatory courses required by each country

Funding information

No funding

References

- 1. General Medical Council . The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum: General Surgery https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/general-surgery-inc_-trauma-tig--approved-jul-17-_pdf-72509288.pdf [accessed 12 May 2019].

- 2. Joint Committee on Surgical Training . Certification Guidelines for General Surgery 2017–18 https://www.jcst.org/quality‐assurance/certification‐guidelines‐and‐checklists/ [accessed 12 May 2019].

- 3. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . CanMEDS Framework http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds‐framework‐e [accessed 8 December 2019].

- 4.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) . ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in General Surgery https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/440_GeneralSurgery_2019.pdf?ver=2019‐06‐19‐092818‐273 [accessed 8 December 2019].

- 5.Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . The SET Program https://www.surgeons.org/trainees/the‐set‐program [accessed 8 December 2019].

- 6. College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA) . Training http://www.cosecsa.org/training [accessed 8 December 2019].

- 7. Elsey EJ, Griffiths G, Humes DJ, West J. Meta‐analysis of operative experiences of general surgery trainees during training. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Madanat R, Mäkinen TJ, Ryan D, Huri G, Paschos N, Vide J; FORTE writing committee. The current state of orthopaedic residency in 18 European countries. Int Orthop 2017; 41: 681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamali P, van Paridon MW, Ibrahim AMS, Paul MA, Winters HA, Martinot‐Duquennoy V et al Plastic surgery training worldwide: Part 1. The United States and Europe. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016; 4: e641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Training authority website for each studied country

Table S2 Minimum operative requirements across countries

Table S3 Academic competencies required by each country

Table S4 Management competencies required by each country

Table S5 Mandatory courses required by each country