Abstract

Prognosis in young patients with breast cancer is generally poor, yet considerable differences in clinical outcomes between individual patients exist. To understand the genetic basis of the disparate clinical courses, tumors were collected from 34 younger women, 17 with good and 17 with poor outcomes, as determined by disease-specific survival during a follow-up period of 17 years. The clinicopathologic parameters of the tumors were complemented with DNA image cytometry profiles, enumeration of copy numbers of eight breast cancer genes by multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization, and targeted sequence analysis of 563 cancer genes. Both groups included diploid and aneuploid tumors. The degree of intratumor heterogeneity was significantly higher in aneuploid versus diploid cases, and so were gains of the oncogenes MYC and ZNF217. Significantly more copy number alterations were observed in the group with poor outcome. Almost all tumors in the group with long survival were classified as luminal A, whereas triple-negative tumors predominantly occurred in the short survival group. Mutations in PIK3CA were more common in the group with good outcome, whereas TP53 mutations were more frequent in patients with poor outcomes. This study shows that TP53 mutations and the extent of genomic imbalances are associated with poor outcome in younger breast cancer patients and thus emphasize the central role of genomic instability vis-a-vis tumor aggressiveness.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and has the highest cancer-related mortality among women worldwide.1 Individuals diagnosed at a young age (<40 years) usually have tumors that are more advanced and more aggressive, resulting in higher recurrence rates and shorter survival, when compared to older patients.2, 3, 4 However, the underlying biological and genetic characteristics associated with less favorable outcomes are not generally agreed upon. Moreover, there is no consensus as to whether young patients should receive different treatments, including more radical surgery.5,6

Extensive studies using gene expression profiling to characterize breast cancers have revealed four distinct molecular subtypes: i) luminal A, ii) luminal B [with either positive or negative erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2; alias HER2) status], iii) HER2 enriched, and iv) triple-negative/basal-like.7,8 These subgroups are clinically categorized into three basic therapeutic groups: i) luminal/estrogen receptor (ER) positive, ii) HER2 amplified, and iii) triple negative/basal like. The ER-positive group is the most common and diverse; patients in this group benefit in particular from endocrine therapy.9,10 The HER2-amplified group is associated with a poor prognosis; however, the introduction of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting this growth factor receptor, has dramatically improved treatment and survival.11, 12, 13 Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancers are more common in patients with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Adjuvant treatment options are restricted to chemotherapy.14 Recent studies have reported that the prevalence of aggressive, triple-negative/basal-like cancers is higher among young women compared to older patients.15, 16, 17 These findings raise the question of whether breast cancers diagnosed at a young age are biologically and genetically unique and should thus be considered as a distinct disease entity, or whether young age is simply associated with a higher prevalence of aggressive molecular subtypes.17,18

The use of gene expression profiling has contributed to the development of molecular signatures for improved prognostication when used in addition to conventional clinicopathologic parameters.10,19,20 Tests for some of these signatures are currently commercially available, such as OncotypeDX (Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA), which is included in the American Society of Clinical Oncology's breast cancer guideline on risk stratification of early stage, node-negative, hormone-receptor–positive and HER2-negative breast cancer.21, 22, 23 In addition, extensive studies measuring nuclear DNA content by either flow cytometry or image cytometry have shown that the degree of gross aneuploidy, that is, genomic instability, determines disease outcome.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Patients with diploid tumors have a significantly better prognosis compared to patients with aneuploid tumors.24, 25, 26, 27 Habermann et al28 previously established a gene expression signature of chromosomal instability that overlapped substantially with established prognostic gene expression signatures. The investigators concluded that the biological basis for prognostic molecular signatures is reflected in the degree of genomic instability as the defining biological property.

The relationship between the degree of genomic instability and levels of intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) remains largely elusive. To understand the interplay between ITH, gross aneuploidy, gene mutations, and disease outcome, we conducted a single-cell genetic analysis by multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH), accompanied by DNA cytometry and targeted sequencing of breast cancers from younger patients with profoundly different clinical outcomes. Our study was motivated by the desire to elucidate biological and genetic features that could explain the generally aggressive nature of breast cancer in younger women.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Samples

This study analyzed 34 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor specimens from a group of younger breast cancer patients with a mean age of 40 years (range, 31 to 59) at diagnosis and a minimum follow-up of 16.7 years. Samples were selected from a cohort of 5618 breast cancer patients who were treated at the Karolinska University Hospital, the Vällingby Clinical Center, as well as other outpatient clinics, in Stockholm, Sweden, between 1986 and 2001. Two equal-sized groups were formed, consisting of 17 patients with short disease-specific survival (DSS; mean survival, 3.6 years; range, 0.7 to 10.3 years) and 17 patients with long DSS (mean survival, 19.1 years; range, 16.7 to 20.9 years). None of the patients in the long survival group died during follow-up. The distribution of aneuploid and diploid tumors (defined in the subsequent paragraph) within the two groups was similar: the short survival group comprised 9 aneuploid cases (52.9%) and 8 diploid cases (47.1%), whereas the long survival group consisted of 6 aneuploid tumors (35.3%) and 11 diploid tumors (64.7%). ER and progesterone receptor (PR) positivity were determined by isoelectric focusing because this was the standard procedure during 1986 to 2001, when the samples were collected.29 Isoelectric focusing is a technique for separating proteins based on their isoelectric point; ER and PR are subsequently detected based on incubation of the gel with radioactively labeled estradiol or promegestrone, respectively, without the use of antibodies.30

The thresholds for ER and PR positivity were set at ≥0.05 fmol/ng DNA.31 HER2 and Ki-67 status were determined by immunohistochemistry.32 The molecular subtypes were determined by applying the criteria specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer and Definition of Surrogate Parameters

| Molecular subtype | Subgroup | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Luminal A | ER/PR+, HER2−, Ki-67 <20% | |

| Luminal B | HER2– | ER/PR+, HER2−, Ki-67 ≥20% |

| HER2+ | ER/PR+, HER2+, any Ki-67 | |

| HER2-enriched | ER/PR−, HER2+, any Ki-67 | |

| Triple negative/basal-like | ER/PR−, HER2−, any Ki-67 |

Molecular subtypes of breast cancer and definition of surrogate parameters.

ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

The threshold for estrogen and progesterone receptor positivity (+) is set at ≥10% positive tumor cells assessed immunohistochemistry. Hormone receptor negativity is defined as ER–/PR–expression of 0% to 9%.

HER2 positivity (+) is defined as a protein overexpression (HER2-score 3+) assessed by immunohistochemistry or a gene amplification assessed by fluorescence in situ hybridization.32

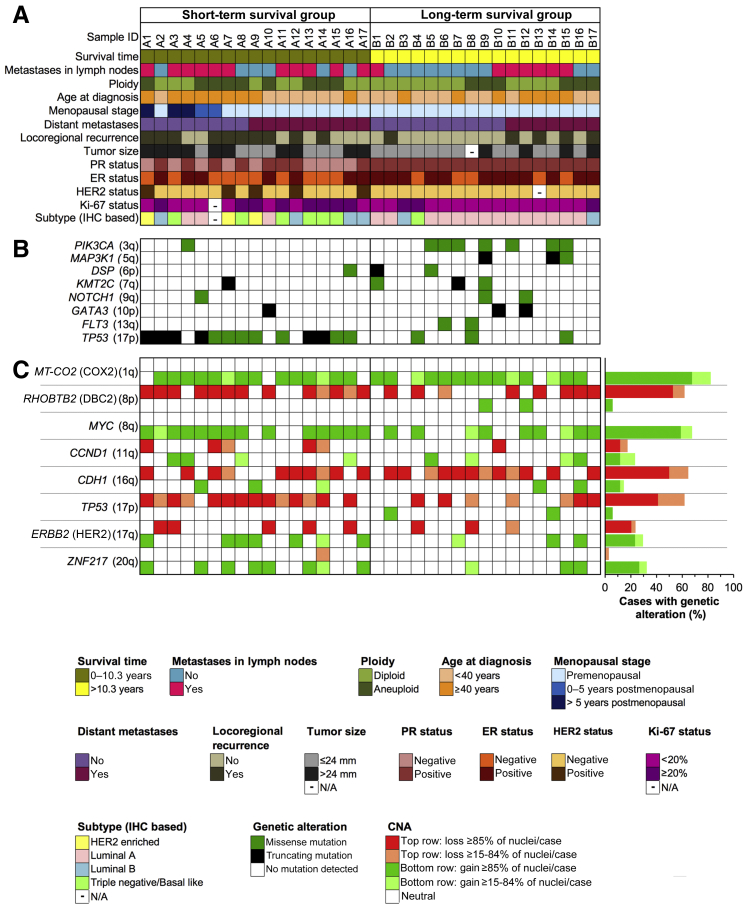

The clinicopathologic data are presented in Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S1. Samples assigned to either of the groups were labeled A for short survivors and B for long survivors. The local Swedish ethics committee approved the use of samples and data for this study (document case number 2013/707-31/3; Office of Human Subjects Research 12758).

Figure 1.

Mutation analysis and multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) results presented for the entire cohort, with corresponding color codes. A: Summary of the clinicopathologic features (rows), plotted per individual case (columns). The patients were divided into two groups characterized by short and long survival. B: Distribution of mutations that affected genes in at least two cases. The color indicates the type of mutations. C: miFISH analysis of eight breast cancer–associated genes. Dark hues indicate gains and losses seen in a major clone, light hues indicate copy number alterations observed only in a minor clone.

Quantitative Measurement of the Nuclear DNA Content by Image Cytometry

Fine-needle aspirates of all tumors were Feulgen stained, and nuclear DNA content was measured quantitatively using static image analysis, which converts the computer-aided extinction coefficient of the stained cells into a ploidy degree, as described by Kronenwett et al.27 The ploidy is visualized as a histogram reflecting the measured tumor cell population. Between 100 and 200 tumor cells and 10 to 20 lymphocytes (serving as a corresponding staining control with a diploid value of 2c) were measured per case. The DNA histograms (Figure 2, C and G; Figure 3, C and G; and Supplemental Figure S1) were then classified according to Auer et al24 into diploid (types I and III) and aneuploid (type IV).

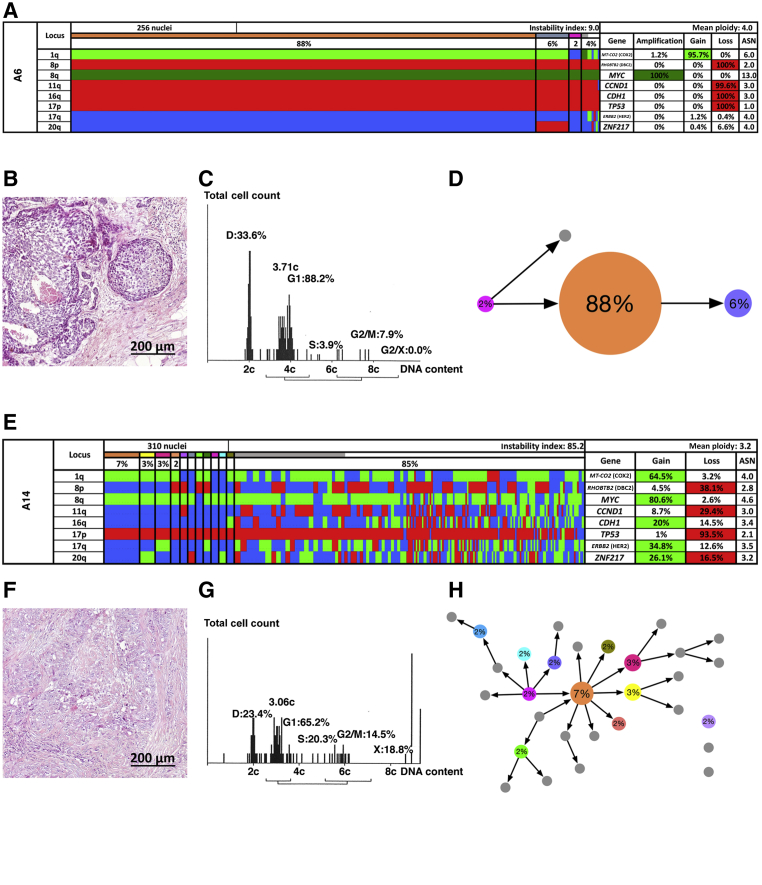

Figure 2.

Patients with short survival. Multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) results (A and E), histology (B and F), image cytometry (C and G), and imbalance clone plots (D and H) for case A6 (A–D) and case A14 (E–H). A and E: Color display of miFISH analysis with eight gene-specific probes. Copy number counts for each nucleus are displayed as gains (green), amplifications (dark green), losses (red) and neutral (blue). Markers are plotted horizontally with the Locus column depicting the specific chromosome arm for each probe on the left of the plot, and the corresponding gene name on the right. Nuclei are plotted vertically by pattern frequency. Each vertical line discerns specific gain and loss patterns and the prevalence of these clones in the population. The Gain and Loss columns refer to the percentage of nuclei in which a gain or loss was observed. The ASN column denotes the mean signal number. Color-labeled percentages indicate a 15% threshold of gain or loss. The Instability Index and the mean ploidy were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. B and F: Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections showing the histomorphology of the respective breast cancers. C and G: Histograms of the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content. The DNA histograms show the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content (x axis) of the tumor cells given in c units. Based on the 2c stemline, the percentages of cells in the G1, S phase and exceeding the G2/M phase of the cell cycle are determined. The brackets visualize the area of the corresponding cells in the G2/M phase. The y axis represents the total cell count; between 100 and 200 tumor cells were measured per case. D and H: Imbalance clone plots visualizing the clonal composition and their putative evolutionary trajectory. The areas of the circles reflect the percentages with which these clones are present. Clones derived by a single gain or loss change are connected by arrows. The arrows indicate the clonal evolution according to gain and loss patterns in the color charts. Clones that are not connected by arrows must have undergone > one gain or loss. Color coding allows for the assignment of the individual clones to the corresponding clones in the color displays in A and E. Scale bars = 200 μm (B and F).

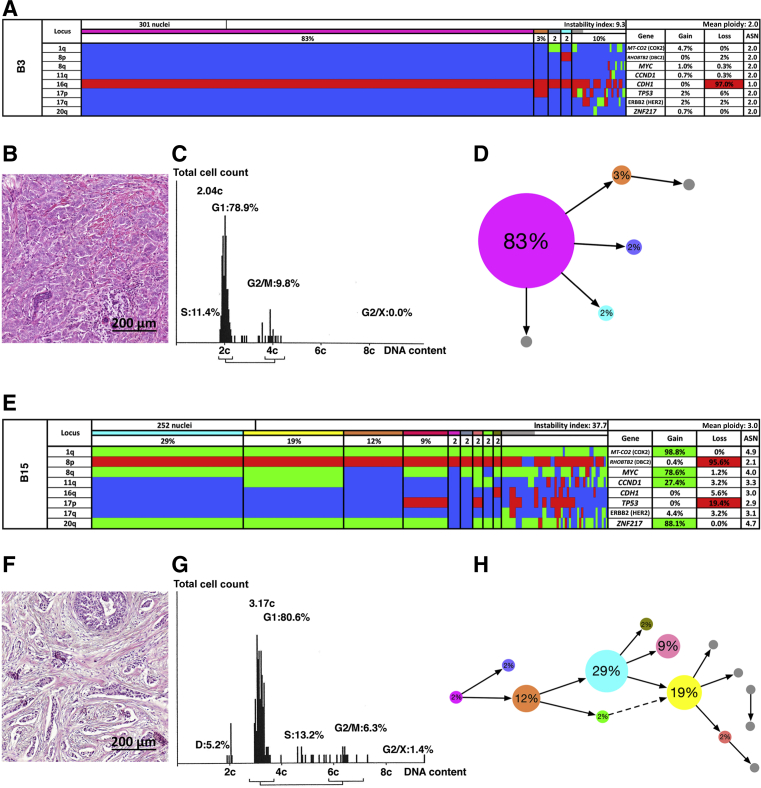

Figure 3.

Patients with long survival. Multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) results (A and E), histology (B and F), image cytometry (C and G), and imbalance clone plots (D and H) for case B3 (A–D) and case B15 (E–H). A and E: Color display of miFISH analysis with eight gene-specific probes. Copy number counts for each nucleus are displayed as gains (green), losses (red), and neutral (blue). Markers are plotted horizontally with the Locus column depicting the specific chromosome arm for each probe on the left of the plot, and the corresponding gene name on the right. Nuclei are plotted vertically by pattern frequency. Each vertical line discerns specific gain and loss patterns and the prevalence of these clones in the population. The Gain and Loss columns refer to the percentage of nuclei in which a gain or loss was observed. The ASN column denotes the mean signal number. Color-labeled percentages indicate a 15% threshold of gain or loss. The Instability Index and the mean ploidy were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. B and F: Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections showing the histomorphology of the respective breast cancer that has been analyzed. C and G: Histograms of the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content. The DNA histograms show the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content (x axis) of the tumor cells given in c units. Based on the 2c stemline, the percentages of cells in the G1, S phase and exceeding the G2/M phase of the cell cycle are determined. The brackets visualize the area of the corresponding cells in the G2/M phase. The y axis represents the total cell count: between 100 and 200 tumor cells were measured per case. D and H: Imbalance clone plots visualizing the clonal composition and their putative evolutionary trajectory. The areas of the circles reflect the percentages with which these clones are present. Clones derived by a single gain or loss change are connected by arrows. The arrows indicate the clonal evolution according to gain and loss patterns in the color charts. Clones that are not connected by arrows must have undergone > one gain or loss. Color coding allows for the assignment of the individual clones to the corresponding clones in the color displays in A and E. Scale bars = 200 μm (B and F).

Multiplex Interphase Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization

To develop miFISH probes that sensitively and specifically hybridize to certain human gene loci, bacterial artificial chromosome contigs were assembled using three to four overlapping clones. Breast cancer–specific probe selection was based on findings from prior analyses of breast cancers using comparative genomic hybridization.33,34 The following probes were included: COX2/MT-CO2 (1q31.1), DBC2/RHOBTB2 (8p21.3), MYC (8q24.21), CCND1 (11q13.3), CDH1 (16q22.1), TP53 (17p13.1), HER2/ERBB2 (17q12), and ZNF217 (20q13.2). Centromere probes CEP4 and CEP10 were used as ploidy references. Clone DNA was extracted, labeled with fluorophores by nick translation, and precipitated as previously published.35,36 Cytospin slides containing single-layered interphase nuclei from two 50-μm–thick unstained formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections per sample were prepared using a modified Hedley method as described.37 Two probe panels consisting of four gene-specific probes and one centromere probe each were consecutively hybridized onto the same cytospin and imaged by the DUET scanning imaging workstation software version 3.6.0.15 (BioView Ltd., Rehovot, Israel). Images were automatically overlaid, so that signal counts of all 10 probes could be enumerated concurrently within each nucleus. All signals were manually counted and reviewed for accuracy using the SOLO workstation (BioView Ltd.) applying the following exclusion criteria: i) overlap with other nuclei, ii) visibly damaged or incomplete nuclei, or iii) insufficient hybridization quality, such as one or more non–clearly discernible probe signals. A mean of 250 nuclei per case (range, 81 to 310) were evaluated.

Determining Clonal Signal Patterns, Gain and Loss Patterns, and Instability Indices

The processing of raw data for the determination of clonal signal patterns was performed as previously described.35 The most common signal pattern in each cell population was defined as the major signal pattern clone. Cellular ploidy was assigned to each signal pattern by integrating mean signal counts of the centromere probes and the eight gene probes, leaving out markers with amplifications to avoid bias of the mean. Gain and loss patterns were determined in relation to the ploidy of the respective nucleus. When we mention that a gene was gained or lost in a sample (Results), or that statistical analyses are reported on gains or losses, only probes for which the respective aberration was present in at least 15% of the evaluated cell population of that sample are included. If a gene was subject to both a gain and a loss above that threshold, it was counted twice. For instance, case A14 (Figure 2E) revealed 10 copy number alterations (CNAs) in total. The ploidy assignments matched, in general, the DNA content measured by image cytometry. Tumor heterogeneity was assessed by the calculation of an instability index per sample, defined as the number of observed signal patterns multiplied by 100 and divided by the number of enumerated cells.37,38 Examples of the miFISH analysis (visualized as gain and loss color displays and imbalance clone plots, as in Figure 2, A and D, and Figure 3, A and D), together with respective hematoxylin and eosin–stained histologic sections and DNA histograms of the tumors, are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Clonal Evolution Assessed by Phylogenetic Tree Modeling

To reconstruct the evolution of tumor progression, the phylogenetic algorithms of FISHtrees software version 3.139 in the ploidyless mode were applied to the eight gene probes analyzed by miFISH. The inferred models based on single-cell gene copy number data include variable probabilities for different gain and loss events of single genes, gains and losses of single chromosomes, and genome doubling as distinct events. An expectation-maximization–like method of assessing CNA-specific and tumor-specific event rates was applied simultaneously with tree reconstruction.39

In each FISHtrees-produced tree, the normal state of the tumor (2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2) is at the root of the inferred model, and each edge moving away from the root to a new node corresponds to i) a change in copy number of one gene, or ii) a change in copy number of an entire chromosome, or iii) a whole-genome duplication (WGD). The first and second aberration types can be distinguished on chromosomes 8 and 17, which contain two gene probes each. The number of steps away from the root is usually called the depth of a node. To test whether the distribution of cells by depths correlates with outcome, the following test was performed. The percentages of cells represented by nodes at each depth in the graph were calculated as described previously.40 This study tested for a significant difference between the mean depths in each group with short- versus long DSS by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

For each of the 34 tumors, the progression of CNAs were modeled by drawing coarse clonal graphs describing the progression among the observed cell types, as distinguished by their probe copy numbers. A graph is inferred from the data on each tumor to minimize heuristically the total number of CNAs across the graph.

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

DNA extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections was done as described previously.41 DNA concentration was measured by Qubit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and DNA quality was assessed on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). A total of 200 ng of DNA was used as input for library preparation. Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed with a capture approach, termed OncoVar, which was designed to sequence coding exons of 563 cancer-related genes (see Hirsch et al42 for gene list). The paired-end libraries, constructed with the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA), were sequenced on the NextSeq 500 system (Illumina). The mean read depth (coverage) of targeted regions was 263. The data-processing and variant-calling procedures in this study mainly followed the Best Practices workflow recommended by the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA).43 The following filtering criteria were used: i) did not pass UnifiedGenotype filter with Genome Analysis Toolkit default criteria, ii) fraction of alternative reads was ≤5%, iii) total read depth was ≤5 and alternative read depth was ≤3, iv) phred-scaled quality score was <30, v) low impact according to database for nonsynonymous SNPs’ functional predictions (dbNSFP),44 vi) common single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the National Center for Biotechnology Information's dbSNP version 147,45 vii) variants with allele frequency, overall allele frequency in ESP (ESP_AF_GLOBAL), or allele frequencies (ESP6500 MAF_EA) of >0.001 in Exome Aggregation Consortium software version 3.1,46 viii) MAPQ score of <40 in variants with ≥100 COSMIC cases or on hotspot genes of breast cancer (TP53, PIK3CA, MAP3K1, GATA3, KMT2C),47 ix) a MAPQ score of <55 in variants on other genes, x) variants existing in more than one sample that do not have ≥100 Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) cases, xi) variants with no COSMIC case that had moderate impact according to dbNSFP. Visual inspection of all identified single-nucleotide variants and indels was performed using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (Broad Institute).48

Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data statistically with regard to the differently formed subgroups, the t-test, the Fisher exact test, or the χ2 test were used as appropriate for calculating the corresponding P values. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used for multiple testing correction. A P value of 0.05 or less after correction for multiple testing was considered significant. Mutual exclusivity analysis of CNAs (COX2, DBC2, MYC, CCND1, CDH1, TP53, HER2, and ZNF217) and mutations (TP53 and PIK3CA) was done using the Mutual Exclusivity Modules in Cancer algorithm from Ciriello et al.49,50

Results

This study presents a comprehensive single-cell genetic analysis of breast cancers occurring in younger patients, none of whom had a BRCA1 mutation. Previous evidence suggested that breast cancers in younger patients, not driven by germline mutations in susceptibility genes, such as BRCA1, are more aggressive compared to tumors in postmenopausal women.2, 3, 4 However, the disease outcome among younger patients does differ significantly. To understand the genetic basis of tumor aggressiveness, 34 samples from younger breast cancer patients were analyzed, 17 each with either short or long survival, treated in Stockholm, Sweden, using DNA-content measurement by image cytometry,27 miFISH with a breast cancer–specific panel for eight gene probes,37 and targeted sequence analysis of a panel of 563 cancer-related genes (OncoVar panel).42 Though these 34 cases were not selected based on the presence or absence of mutations in germline susceptibility genes, none of the patients' tumor DNA showed evidence of such mutations in the OncoVar analysis.

Clinical Data

The age at diagnosis in the cohort ranged from 31 to 59 years (mean, 40 years). The overall cohort of 34 patients comprised two groups with respect to DSS, assessed during a minimum follow-up period of 16.7 years. The mean DSS in the first group (n = 17) was <4 years, whereas the second group had a mean DSS of 19.1 years. Figure 1 summarizes the clinical data, including age at diagnosis; menopausal stage; tumor size; presence of lymph node metastases; disease progress as defined by locoregional recurrence or distant metastases; survival time; nuclear DNA content (ploidy); PR, ER, HER2, and Ki-67 status; and miFISH and sequencing results from the entire cohort. A detailed summary of the clinicopathologic data is presented in Supplemental Table S1.

DNA Ploidy Measurements

DNA ploidy, assessed by quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content by image cytometry, provides prognostic information independent of clinical parameters; patients with aneuploid tumors (Auer IV) have a poorer prognosis compared to patients with diploid tumors (Auer I/III) (for classification details, see Auer et al24 and Materials and Methods). To account for this correlation and to assess the influence of the degree of ITH on disease outcome as determined by miFISH, the short and long survival groups were matched for DNA ploidy levels and, consequently, consisted of both diploid and aneuploid tumors. Examples of the DNA ploidy measurements are provided in Figure 2, C and G; Figure 3, C and G; and Supplemental Figure S1.

Molecular Subtypes

All four molecular breast cancer subtypes as defined in Table 1, that is, luminal A, luminal B, HER2 enriched, and triple negative/basal like, were present in the current study cohort (Figure 1). The three HER2-enriched tumors in the cohort occurred exclusively in the short survival group (P = 0.137). Luminal B tumors occurred at a similar rate in the short and long survival groups (P = 0.398). Triple-negative tumors occurred at a similar rate between the good- and poor-prognosis groups (P = 0.0782). The good-prognosis group was dominated by luminal A tumors (P = 0.0016).

Copy Number Alterations and Intratumor Heterogeneity

An approach to visualize up to 20 gene and/or centromere probes simultaneously on a single-cell basis, termed miFISH,37 which provides a quantitative assessment of CNAs and ITH in cancer cell populations, was recently developed. The eight breast cancer–specific probes used in this study target the following genes: COX2 (1q), DBC2 (8p), MYC (8q), CCND1 (11q), CDH1 (16q), TP53 (17p), HER2 (17q), and ZNF217 (20q). Probes targeting the centromeres of chromosomes 4 and 10 were included to provide additional information about the overall ploidy of the individual cells. All of the 34 cases showed CNAs in at least one of the selected gene markers. A minimum of 245 nuclei per case were counted, with the exceptions of cases B6 (81 counted nuclei) and B8 (158 counted nuclei) due to sparsity of cells. Gains in COX2 (28/34, 82.4%), MYC (23/34, 67.7%) and losses of CDH1 (22/34, 64.7%), DBC2 (21/34, 61.8%), and TP53 (21/34, 61.8%) were the most common alterations. CNAs of other gene loci happened in <11 of the cases (32.4%). With the exception of CCND1 (11q) and HER2 (17q), genes that were frequently gained were rarely lost, and vice versa. Consistent with previous results, probes targeting oncogenes on 1q (COX2), 8q (MYC), 11q (CCND1), 17q (HER2), and 20q (ZNF217) were more often subject to copy number gains, while probes representing tumor suppressor genes on 8p (DBC2), 16q (CDH1), and 17p (TP53) were more often subject to copy number losses.37 However, wild-type TP53 was gained in two cases (B2 and B14). In addition to the overall assessment of CNAs per case on a single-cell basis, miFISH allowed for an evaluation of ITH in the tumor cell population as a whole. This evaluation revealed a high variability in ITH across the sample cohort. Instability indices (Materials and Methods) ranged from 2.0 to 85.2 (median, 14.05), and the number of clones in the gain and loss patterns (threshold, >2% of the cells) ranged from 1 to 30. Examples of the miFISH analysis are shown in Figures 2 and 3. These cases represent a wide-range spectrum of levels of ITH, illustrating the genetic diversity of breast cancer in younger women.

Figure 2, A–H, shows two examples of the miFISH analysis of tumors associated with short survival. Case A6 (Figure 2, A–D) revealed a major clone (88% of the cells) that was dominated by a gain of COX2, amplification of MYC, and losses of DBC2, CCND1, CDH1, TP53, and HER2. The instability index (Materials and Methods) was 9.0. In contrast, the instability index of case A14 (Figure 2, E–H) was determined to be 85.2, which reflects the lack of a dominant clone. However, despite this enormous instability across the tumor cell population, this study identified a gain of COX2 in 64.5%, a gain of MYC in 80.6%, and a loss of TP53 in 93.5% of the cells. Additional CNAs were detected in DBC2 (loss in 38.1%), CCND1 (loss in 29.4%), CDH1 (gain in 20%), HER2 (gain in 34.8%), and ZNF217 (gain in 26.1%).

Figure 3, A, D, E, and H, shows two examples of miFISH results in tumors associated with long survival. Case B3 (Figure 3, A–D) revealed a major clone in 83% with a loss of CDH1 as the sole clonal event (instability index, 9.3). In case B15 (Figure 3, E–H), on the other hand, an instability index of 37.7, and four major clones in 29%, 19%, 12%, and 9% of the cell population, respectively, were observed. The most recurrent copy number increases were mapped to 1q (COX2), 8q (MYC), and 20q (ZNF217), and losses on 8p (DBC2).

In general, the results of the miFISH analyses aligned well with the DNA histograms (Figure 2, A, C, E, and G, and Figure 3, A, C, E, and G). Case B3 (Figure 3, A–D), for example, was diploid and genomically stable, whereas case A14 (Figure 2, E–H) was defined by a widely divergent nuclear DNA content, exemplifying a highly instable case. The color charts and the DNA histograms for the remaining 30 cases are shown in Supplemental Figure S1.

Patterns of clonal evolution in these four representative tumor samples are also presented as imbalance clone plots to visualize the trajectory and frequency of clones depicted in the color chart (Figure 2, D and H, and Figure 3, D and H). Note the different patterns, such as when comparing case B3 and A14, that represent diploid and aneuploid tumors, respectively. We emphasize that, in general, we observed cases that either revealed a dominant clone (eg, cases A6 and B3) or displayed an intermediate (eg, case B15) or high degree of complexity indicating ongoing chromosomal instability (eg, case A14).

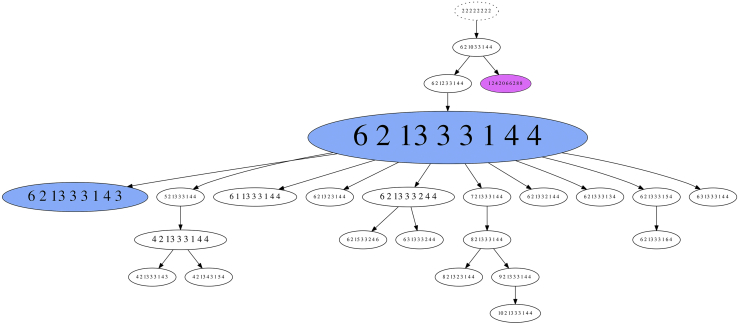

Phylogenetic Tree Modeling

To infer phylogenetic trees based on the miFISH data, the specifically developed FISHtrees software package version 3.1 was used,39 which allowed for the reconstruction of clonal relationships based on gene CNAs, single chromosomal segregation errors, and WGD. An example of such an analysis is shown in case A6 (Figure 4). The FISHtrees-based analysis demonstrated the emergence of a major tetraploid clone with a specific signal pattern distribution, from which the majority of the observed signal counts in the daughter cells could be explained by individual chromosomal segregation errors. The signal counts in one cell were consistent with WGD, which either happened shortly before sampling, or did not result in a fitness advantage. Despite ongoing chromosomal instability, the distribution pattern of genomic imbalances observed in the major clones dominated the tumor cell population as a whole.

Figure 4.

FISHtrees analysis of case A6. The FISHtrees result shows the clonal evolution. Details of the analysis are described in Materials and Methods. FISH patterns are depicted in the following gene order: MT-CO2 (COX2), RHOBTB2 (DBC2), MYC, CCND1, CDH1, TP53, ERBB2 (HER2), and ZNF217. The size of the nodes reflects, but is not proportional to, the frequency of the patterns in the cell population. The blue-labeled node indicates the presence of the major tetraploid clone (pattern 6-2-13-3-3-1-4-4) and a smaller tetraploid clone (pattern 6-2-13-3-3-1-4-3). The pink clone (pattern 12-4-20-6-6-2-8-8) reflects a whole-genome duplication event.

Generally, WGD was observed in 10 aneuploid tumors (66%) and 8 diploid tumors (42%) tumors; however, it was usually assigned to tree edges leading to terminal nodes. The FISHtrees analysis showed a trend toward a higher tree depth in the short survival group (P = 0.07763). Yet both simple and complex trees were present in patients with short or long survival.

Landscape of Gene Mutations

To assess the protein-altering mutations in the tumor samples, targeted sequence analysis of 563 cancer-related genes included in the OncoVar panel were used.42 The most frequently mutated genes are presented in Figure 1. A list comprising all detected mutations is presented in Supplemental Table S2. Overall, the spectrum of gene mutations observed in this cohort overlaps with the most frequently mutated genes reported in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) 2012 breast cancer cohort, except for CDH1, which did not show any mutation in the current study cohort, and DSP and FLT3, which have not been reported to be frequently mutated in the TCGA cohort.51 Genes that were mutated in at least two cases in the current study cohort include PIK3CA, MAP3K1, DSP, KMT2C, NOTCH1, GATA3, FLT3, and TP53. Across the samples, TP53 (n = 16) and PIK3CA (n = 8) were the most commonly mutated genes. The overall mutation burden was not significantly different between the outcome groups.

The distribution of mutations across the protein domains was visualized (Supplemental Figure S2) for the most frequently mutated genes in our cohort (PIK3CA and TP53). The majority of TP53 mutations occurred as missense mutations, primarily mapping to the DNA binding domain. Mutations in PIK3CA also occurred mostly as missense mutations, involving the known mutation hotspots.

Genetic Characteristics of Clinical and Ploidy Subgroups

The patients in the cohort were selected because they showed profound differences in their clinical outcomes without any prior knowledge of the genomic characteristics of their tumors. In one group, the mean survival time was 3.6 years, compared to 19.1 years in the juxtaposed group. The goal of this study was to understand whether the profound differences in survival between the groups could be explained by the results on the genetic parameters assessed by miFISH and mutation analysis.

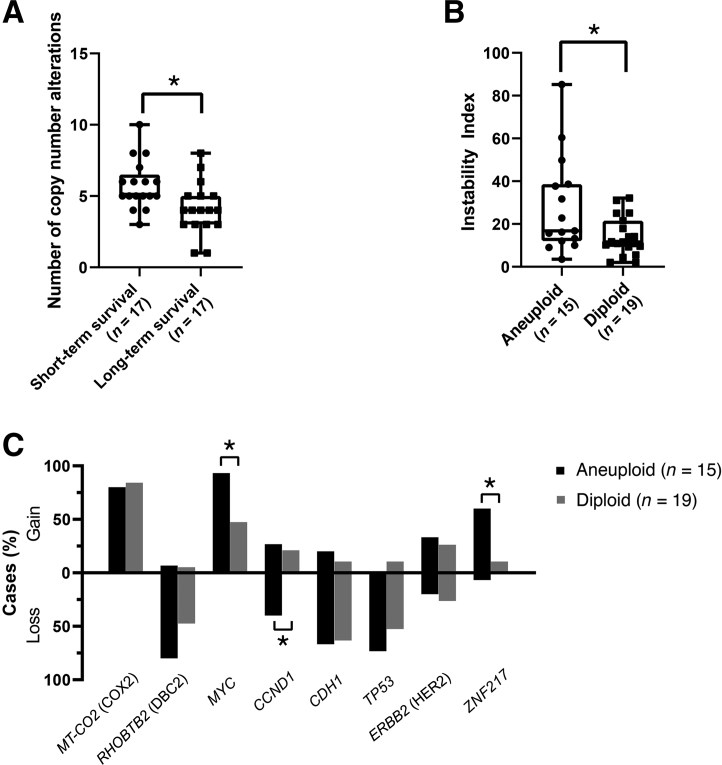

MiFISH analysis showed a significant difference in the number of CNAs between the short and long survival groups: The tumors in the good-prognosis group had a mean of 4.3 CNAs per case, while the number in the poor-prognosis group was increased to 5.8 (P = 0.011) (Figure 5A). Of note, a nonsignificant trend toward a higher mean instability index as a reflection of ITH was observed in the poor-prognosis group (23.5 versus 16.7; P = 0.283). This was also true for higher percentages of cases with TP53 loss (83% versus 44%; P = 0.448), HER2 gains (41% versus 20%; P = 0.604), and ZNF217 gains (47% versus 20%; P = 0.49). However, the differences did not reach statistical significance. Mutation analysis revealed that TP53 mutations were exclusively observed in the group with short survival (P = 0.0016), whereas PIK3CA mutations were significantly more common in the group with long survival (P = 0.041) (Figure 1). With the co-occurrence of TP53 mutations and TP53 losses in the poor-prognosis group, there was a complete functional loss of this tumor suppressor in 64.7% (11/17) of cases. This phenomenon was observed in only 17.6% (3/17) of the long survival group (P = 0.013). Differences in the mutation frequency of other genes lacked significance. In contrast, mutation analysis did not reveal a significant difference between the diploid and aneuploid groups.

Figure 5.

Results of the multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) analysis showing the frequency of copy number alterations (CNAs) and Instability Indices. A: Total number of CNAs of the short and long survival groups. Note the significant difference between the subgroups. B: Instability indices of the ploidy subgroups, calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Note the significant difference between aneuploid and diploid cases. C: Percentage of cases showing a gain or loss in the eight targeted genes. The differences in MYC, CCND1, and ZNF217 are significant between the aneuploid and diploid subgroups. Data are expressed as medians (ranges) and outliers. ∗P < 0.05.

Next, it was investigated whether the gene-specific CNAs and mutations were correlated to ploidy groups defined by DNA cytometry. Tumors were classified as either diploid or aneuploid according to parameters described in Materials and Methods and consistent with previous classifications.24 Figure 5B illustrates the degree of ITH (in terms of instability indices that were calculated as described in Materials and Methods) assessed by miFISH, which revealed a significant difference between the aneuploid and diploid tumors (mean instability index, 23.48 versus 16.66; P = 0.037) (Figure 5B). This finding is consistent with previous results.35 In terms of gene-specific CNAs, significantly higher copy numbers of both MYC and ZNF217 were observed in the aneuploid cases (P = 0.037 and 0.028, respectively). Conversely, aneuploid cases showed more frequent losses of CCND1 (P = 0.028), which might be a reflection of overall chromosomal instability (Figure 5C).

Another observed trend was that TP53 mutations were slightly more common in the aneuploid tumors (66.7% versus 31.6%; P = 0.0718), whereas PIK3CA mutations were slightly more common in the diploid tumors (31.6% versus 13.3%; P = 0.2569) (Figure 1). However, these findings did not reach statistical significance.

In summary, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of younger breast cancer patients with either short or long survival. The burden of somatically acquired CNAs, as well as the presence of mutations in TP53, confer a poor prognosis.

Discussion

Young women with breast cancer often face a more severe clinical course with a shorter DSS compared to those in older patients.17,52 This observation, however, is not universally applicable, and the complex biology of breast cancer in young women, with its potentially aggressive features, remains poorly understood.53 This study addressed the variability in disease outcome by selecting younger breast cancer patients with short and long survival (mean DSS, <4 versus >19 years) from over 5000 cases treated in the greater Stockholm area between 1986 and 2001. The potential genetic basis of the disparate outcome was explored by determining the genetic instability profile using miFISH, which allows for the enumeration of copy numbers of cancer genes in individual cells across the tumor cell population and an assessment of the degree of ITH. The mutation status of 563 cancer genes was determined by targeted sequence analysis. DNA ploidy was determined by image cytometry.

The role of DNA ploidy for prognostication has been firmly established. Specifically, patients with diploid tumors have a greatly improved prognosis compared to patients with aneuploid tumors.24, 25, 26, 27 A comprehensive retrospective analysis of the complete cohort comprising over 4000 patients confirmed the dominant role of certain parameters of the DNA ploidy profiles as a predictor of disease outcome in breast cancer patients, independent of commonly used clinical parameters,54 particularly in the group of premenopausal patients. This study has therefore accounted for this independent prognostic parameter by matching the number of diploid and aneuploid tumors in our two outcome groups to assess the influence of additional parameters, such as the burden of specific CNAs, the degree of ITH, and gene mutations, on disease outcome.

miFISH was used to enumerate CNAs of five breast cancer–relevant oncogenes (COX2, MYC, CCND1, HER2, and ZNF217) and three tumor suppressor genes (DBC2, CDH1, and TP53). This method allowed for the identification of specific genomic imbalances in individual cases on a single-cell level, precise calculation of genomic instability indices, and measurement of the degree of ITH.

In the current study cohort of 34 patients, gains of COX2 and MYC were most commonly observed, accompanied by losses of CDH1, DBC2, and TP53. These findings are consistent with previous results based on comparative genomic hybridization33,34 and with results reported in the TCGA database.51 The co-occurrence of a loss of DBC2 (8p) and gain of MYC (8q) in 8 cases (23.5%) (Figure 1), which was observed equally in both survival groups, suggest the formation of an isochromosome 8q. This interpretation is supported by the spatial distribution of the FISH signals in interphase nuclei (data not shown). A significantly higher co-occurrence of a DBC2 loss and MYC gain in the whole cohort (P = 0.002) was also observed in our mutual exclusivity analysis (data not shown) interrogating copy numbers of the eight genes analyzed by miFISH, and the two most frequently mutated genes in our breast cancer cohort, TP53 and PIK3CA. Loss of the short arm of chromosome 8 has been frequently reported in many human carcinomas,55 including breast cancers, indicating a significant pathogenic role of DBC2 and additional putative tumor suppressor genes on this chromosome arm.56,57

This analysis also observed, somewhat unexpectedly, frequent losses of HER2 (8/34), which is located on 17q and could possibly be explained by the fact that the loss of the entire chromosome 17 is driven by the necessity to lose a copy of TP53, which resides on 17p. In fact, all cases that have a loss of HER2 show a concomitant loss of TP53. Seven cases with TP53 loss revealed concomitant HER2 gain; however, surprisingly, based on the spatial distribution of the signals of TP53 and HER2 in interphase nuclei, an isochromosome 17q formation could not be deduced in our samples (data not shown), although isochromosome 17q has been previously described as a frequent alteration in breast and other cancers.58

CCND1 gains occurred in only eight cases of the overall cohort (8/34, 23.5%) and were equally distributed in the short and long survival groups. Three of them (8.8%) presented gains that exceeded more than two times the assigned overall ploidy and were thus defined as amplifications. CCND1 amplifications are observed in around 10% to 20% of primary breast cancers, preferentially in ER-positive tumors, and have been reported to predict poor response to adjuvant endocrine treatment and poor prognosis.59,60 Counterintuitively, two CCND1-amplified, ER-positive cases were in the long survival group (B5, B16) and only one was a short survivor (A4) (Supplemental Figure S1) Also of interest, copy number gains and losses of CCND1 in the overall cohort were observed with similar frequencies (gains in eight cases versus losses in six cases), which might be a reflection of overall chromosomal instability. Chromosome 11q losses in breast cancer have been described, suggesting the tumor suppressor genes ATM (coding for a protein involved in DNA repair and cell cycle control) and CHEK1 (cell cycle checkpoint kinase) as putative candidates.61,62

WGD, that is tetraploidization, has been reported as a frequent phenomenon in cancers associated with poor prognosis.63 The miFISH results revealed signal patterns consistent with WGD in 10 aneuploid tumors (66%) and 8 diploid tumors (42%) (data not shown). Therefore, it is concluded that high genomic instability is not a prerequisite of WGD. It is also noted that in many cases, such as case A6 (Figure 4), WGD did not result in the expansion of clones that underwent tetraploidization. This finding indicates that WGD does not necessarily seem to reflect a selective advantage, and that WGD occurs in, but is not required for, breast cancer in younger patients. CNAs were significantly more common in the poor-prognosis group (Figure 5A). This finding is consistent with previous results based on comparative genomic hybridization, which has been performed in an age-unbiased breast cancer cohort.64

However, a high number of copy number–altered loci did not necessarily reflect increased ITH in the cohort; in other words, cases with abundant CNAs can be stable, as reflected by a low instability index, which is supported by the statistical analysis revealing no significant difference in the instability indices between the survival groups (P = 0.283). This observation can be convincingly exemplified in case A6: CNAs were detected for six of the eight genes tested. At the same time, the major clone of gains and losses comprised 88% of the tumor cell population, that is, the instability index was low (9.0) (Figure 2A). A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be that the presence of many CNAs in individual tumors results in the deregulation of multiple signaling pathways relevant in breast cancer: in tumors that have a high number of CNAs and low ITH, a high degree of ITH does not seem to provide an additional decisive fitness advantage.

In two cases, clonal CNAs of only one of the analyzed genes [either the gain of COX2 (case B1) or the loss of CDH1 (case B3)] (Supplemental Figure S1 and Figure 3), in the absence of ITH or mutations in the tested genes, were sufficient to cause cancer. Notably, this pattern was observed only in the group with long survival.

This study generally observed qualitative similarities between the DNA ploidy levels, assessed by image cytometry, and ITH, determined by miFISH: aneuploid tumors had a significantly higher degree of ITH, with a mean instability index of 28.2 compared to 14.1 in diploid tumors (Figure 5B). This implies that the cellular mechanisms that result in genomic instability, that is, gross aneuploidy, may be similar to the ones that determine the degree of ITH.

We assume that matching diploid and aneuploid cases in both prognostic groups explains our observation that the degree of ITH was not significantly different between the survival groups. Thus, the results from this cohort probably do not mirror the distribution of instability patterns in randomly selected younger breast cancer patients. We would like to emphasize, however, that a significant difference in the abundance of CNAs was observed.

In general, mutation spectra overlapping those reported in the TCGA database were observed.7,51 We therefore conclude that the overall mutation spectrum in younger patients is not different from that in an age-unbiased cohort of breast cancer patients. Furthermore, mutation analysis revealed two significant differences between the outcome groups. First, PIK3CA somatic mutations occurred predominantly in the long survival group. This finding is consistent with findings from a previous study showing that PIK3CA mutations were more common in luminal A tumors, which are associated with the best prognosis among the defined molecular subtypes.51 Strikingly, TP53 mutations were predominantly found in the poor-prognosis group. This finding is consistent with previous results.51 With only two exceptions, TP53 was either lost or mutated, or both, in the group with poor outcome.

Taken together, the spectra of gene mutations and CNAs observed in breast cancers from younger patients are not different from those from an age-unbiased cohort. Poor outcome in younger breast cancer patients was linked to TP53 mutations and a higher number of genomic imbalances, corroborating the central role of chromosomal instability with respect to tumor aggressiveness and disease prognostication in younger breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaolin Wu, Arati Razuiddin, Bao Tran, and Jyoti Shetty (Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) for sequencing; Dr. Reinhard Ebner for crucial comments on the manuscript; and Buddy Chen for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, and National Library of Medicine; the German Foundation for Young Adults with cancer (Deutsche Stiftung für junge Erwachsene mit Krebs) (A.K.); the Ad Infinitum Foundation (A.L. and N.D.); and a Mildred Scheel postdoctoral fellowship of the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe) (D.H.).

Disclosure: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.04.015.

Supplemental Data

Multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) results and image cytometry for all cases with the exception of A6, A14, B3, and B15, which are shown in the main body of the manuscript (Figure 2, A and E, and Figure 3, A and E). Color display of miFISH analysis with eight gene-specific probes. Copy number counts for each nucleus are displayed as gains (green), amplifications (dark green), losses (red), and neutral (blue). Markers are plotted horizontally with the Locus column depicting the specific chromosome arm for each probe on the left of the plot, and the corresponding gene name on the right. Nuclei are plotted vertically by pattern frequency. Each vertical line discerns specific gain and loss patterns and the prevalence of these clones in the population. The Gain and Loss columns refer to the percentages of nuclei in which a gain or loss was observed. Color-labeled percentages indicate a 15% threshold of gain or loss. The instability index and the mean ploidy were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Histograms of the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content, when available, are shown below the color displays of the respective cases. The DNA histograms show the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content (x axis) of the tumor cells given in c units. Based on the 2c stemline, the percentages of cells in the G1, S-phase and exceeding the G2/M phase of the cell cycle are determined. The parentheses visualize the area of the corresponding cells in the G2/M phase. The y axis represents the total cell count: between 100 and 200 tumor cells were measured per case.

A and B: Lolliplot chart of the mutation sites in PIK3CA (A) and TP53 (B). A: Mutations are mapped on the linear protein and its domains from the Protein family database (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute; lollipop plot). The different domains of PIK3CA are marked in color: TP53 transactivation motif (5 to 29) in green, TP53 DNA binding domain (95 to 289) in red, and TP53 tetramerization motif (319 to 358) in blue. PI3-kinase family, p85-binding domain (32 to 108) in green; PI3-kinase family, Ras-binding domain (174 to 291) in red; phosphoinositide 3-kinase C2 (351 to 483) in blue; phosphoinositide 3-kinase family, accessory domain (PIK domain) (520 to 703) in yellow; and phosphatidylinositol 3- and 4-kinase (798 to 1014) in purple. Lollipops: green, missense mutation; black, truncating mutation. B: Mutations are mapped on the linear protein and its domains from the Protein family database. The different domains of TP53 are marked in color: TP53 transactivation motif (5 to 29) in green, TP53 DNA binding domain (95 to 289) in red, and TP53 tetramerization motif (319 to 358) in blue. Lollipops: green, missense mutation; black, truncating mutation.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adami H.O., Malker B., Holmberg L., Persson I., Stone B. The relation between survival and age at diagnosis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:559–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608283150906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nixon A.J., Neuberg D., Hayes D.F., Gelman R., Connolly J.L., Schnitt S., Abner A., Recht A., Vicini F., Harris J.R. Relationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:888–894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Saghir N.S., Seoud M., Khalil M.K., Charafeddine M., Salem Z.K., Geara F.B., Shamseddine A.I. Effects of young age at presentation on survival in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sariego J. Breast cancer in the young patient. Am Surg. 2010;76:1397–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azim H.A., Jr., Partridge A.H. Biology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:427. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0427-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perou C.M., Sorlie T., Eisen M.B., van de Rijn M., Jeffrey S.S., Rees C.A., Pollack J.R., Ross D.T., Johnsen H., Akslen L.A., Fluge O., Pergamenschikov A., Williams C., Zhu S.X., Lonning P.E., Borresen-Dale A.L., Brown P.O., Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorlie T., Perou C.M., Tibshirani R., Aas T., Geisler S., Johnsen H., Hastie T., Eisen M.B., van de Rijn M., Jeffrey S.S., Thorsen T., Quist H., Matese J.C., Brown P.O., Botstein D., Lonning P.E., Borresen-Dale A.L. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van't Veer L.J., Dai H., van de Vijver M.J., He Y.D., Hart A.A., Mao M., Peterse H.L., van der Kooy K., Marton M.J., Witteveen A.T., Schreiber G.J., Kerkhoven R.M., Roberts C., Linsley P.S., Bernards R., Friend S.H. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paik S., Shak S., Tang G., Kim C., Baker J., Cronin M., Baehner F.L., Walker M.G., Watson D., Park T., Hiller W., Fisher E.R., Wickerham D.L., Bryant J., Wolmark N. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slamon D.J., Clark G.M., Wong S.G., Levin W.J., Ullrich A., McGuire W.L. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergamaschi A., Kim Y.H., Wang P., Sorlie T., Hernandez-Boussard T., Lonning P.E., Tibshirani R., Borresen-Dale A.L., Pollack J.R. Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin K., DeVries S., Fridlyand J., Spellman P.T., Roydasgupta R., Kuo W.L., Lapuk A., Neve R.M., Qian Z., Ryder T., Chen F., Feiler H., Tokuyasu T., Kingsley C., Dairkee S., Meng Z., Chew K., Pinkel D., Jain A., Ljung B.M., Esserman L., Albertson D.G., Waldman F.M., Gray J.W. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perou C.M. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 5:39–48. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S5-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer K.R., Brown M., Cress R.D., Parise C.A., Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109:1721–1728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancello G., Maisonneuve P., Rotmensz N., Viale G., Mastropasqua M.G., Pruneri G., Veronesi P., Torrisi R., Montagna E., Luini A., Intra M., Gentilini O., Ghisini R., Goldhirsch A., Colleoni M. Prognosis and adjuvant treatment effects in selected breast cancer subtypes of very young women (<35 years) with operable breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1974–1981. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anders C.K., Fan C., Parker J.S., Carey L.A., Blackwell K.L., Klauber-DeMore N., Perou C.M. Breast carcinomas arising at a young age: unique biology or a surrogate for aggressive intrinsic subtypes? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e18–e20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partridge A.H., Hughes M.E., Warner E.T., Ottesen R.A., Wong Y.N., Edge S.B., Theriault R.L., Blayney D.W., Niland J.C., Winer E.P., Weeks J.C., Tamimi R.M. Subtype-dependent relationship between young age at diagnosis and breast cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3308–3314. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.8013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Vijver M.J., He Y.D., van't Veer L.J., Dai H., Hart A.A., Voskuil D.W., Schreiber G.J., Peterse J.L., Roberts C., Marton M.J., Parrish M., Atsma D., Witteveen A., Glas A., Delahaye L., van der Velde T., Bartelink H., Rodenhuis S., Rutgers E.T., Friend S.H., Bernards R. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sotiriou C., Wirapati P., Loi S., Harris A., Fox S., Smeds J., Nordgren H., Farmer P., Praz V., Haibe-Kains B., Desmedt C., Larsimont D., Cardoso F., Peterse H., Nuyten D., Buyse M., Van de Vijver M.J., Bergh J., Piccart M., Delorenzi M. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andre F., Ismaila N., Henry N.L., Somerfield M.R., Bast R.C., Barlow W., Collyar D.E., Hammond M.E., Kuderer N.M., Liu M.C., Van Poznak C., Wolff A.C., Stearns V. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update-integration of results From TAILORx. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1956–1964. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardoso F., van't Veer L., Rutgers E., Loi S., Mook S., Piccart-Gebhart M.J. Clinical application of the 70-gene profile: the MINDACT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:729–735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sparano J.A., Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:721–728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auer G., Eriksson E., Azavedo E., Caspersson T., Wallgren A. Prognostic significance of nuclear DNA content in mammary adenocarcinomas in humans. Cancer Res. 1984;44:394–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornelisse C.J., van de Velde C.J., Caspers R.J., Moolenaar A.J., Hermans J. DNA ploidy and survival in breast cancer patients. Cytometry. 1987;8:225–234. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990080217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fallenius A.G., Auer G.U., Carstensen J.M. Prognostic significance of DNA measurements in 409 consecutive breast cancer patients. Cancer. 1988;62:331–341. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880715)62:2<331::aid-cncr2820620218>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronenwett U., Huwendiek S., Ostring C., Portwood N., Roblick U.J., Pawitan Y., Alaiya A., Sennerstam R., Zetterberg A., Auer G. Improved grading of breast adenocarcinomas based on genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2004;64:904–909. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habermann J.K., Doering J., Hautaniemi S., Roblick U.J., Bundgen N.K., Nicorici D., Kronenwett U., Rathnagiriswaran S., Mettu R.K., Ma Y., Kruger S., Bruch H.P., Auer G., Guo N.L., Ried T. The gene expression signature of genomic instability in breast cancer is an independent predictor of clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1552–1564. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wrange O. Isoelectric focusing of steroid hormone receptors in slabs of polyacrylamide gel. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1983;3:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01806240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wrange O., Humla S., Ramberg I., Nordenskjold B., Gustafsson J.A. Estrogen and progestin receptor analysis in human breast cancer by isoelectric focusing in slabs of polyacrylamide gel. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1984;91:32–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-82188-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wrange O., Nordenskjold B., Gustafsson J.A. Cytosol estradiol receptor in human mammary carcinoma: an assay based on isoelectric focusing in polyacrylamide gel. Anal Biochem. 1978;85:461–475. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lebeau A., Denkert C., Sinn P., Schmidt M., Wockel A. [Update of the German S3 breast cancer guideline: what is new for pathologists?] Pathologe. 2019;40:185–198. doi: 10.1007/s00292-019-0578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kallioniemi A., Kallioniemi O.P., Piper J., Tanner M., Stokke T., Chen L., Smith H.S., Pinkel D., Gray J.W., Waldman F.M. Detection and mapping of amplified DNA sequences in breast cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2156–2160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ried T., Just K.E., Holtgreve-Grez H., du Manoir S., Speicher M.R., Schrock E., Latham C., Blegen H., Zetterberg A., Cremer T., Auer G. Comparative genomic hybridization of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded breast tumors reveals different patterns of chromosomal gains and losses in fibroadenomas and diploid and aneuploid carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5415–5423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oltmann J., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Hernandez L.S., Meyer R., Torres I., Hu Y., Doberstein N., Killian J.K., Petersen D., Zhu Y.J., Edelman D.C., Meltzer P.S., Schwartz R., Gertz E.M., Schaffer A.A., Auer G., Habermann J.K., Ried T. Aneuploidy, TP53 mutation, and amplification of MYC correlate with increased intratumor heterogeneity and poor prognosis of breast cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2018;57:165–175. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiedler D., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Hirsch D., Hernandez L.S., Torres I., Wangsa D., Hu Y., Zapata L., Rueschoff J., Belle S., Ried T., Gaiser T. Single-cell genetic analysis of clonal dynamics in colorectal adenomas indicates CDX2 gain as a predictor of recurrence. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1561–1573. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Berroa Garcia L.Y., Bradley A., Ortiz-Melendez C., Lee W.J., Christensen R., Prindiville S.A., Calzone K.A., Soballe P.W., Hu Y., Chowdhury S.A., Schwartz R., Schaffer A.A., Ried T. Single-cell genetic analysis of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer reveals enormous tumor heterogeneity yet conserved genomic imbalances and gain of MYC during progression. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1807–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heselmeyer-Haddad K.M., Berroa Garcia L.Y., Bradley A., Hernandez L., Hu Y., Habermann J.K., Dumke C., Thorns C., Perner S., Pestova E., Burke C., Chowdhury S.A., Schwartz R., Schaffer A.A., Paris P.L., Ried T. Single-cell genetic analysis reveals insights into clonal development of prostate cancers and indicates loss of PTEN as a marker of poor prognosis. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2671–2686. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhury S.A., Gertz E.M., Wangsa D., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Ried T., Schaffer A.A., Schwartz R. Inferring models of multiscale copy number evolution for single-tumor phylogenetics. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:i258–i267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wangsa D., Chowdhury S.A., Ryott M., Gertz E.M., Elmberger G., Auer G., Avall Lundqvist E., Kuffer S., Strobel P., Schaffer A.A., Schwartz R., Munck-Wikland E., Ried T., Heselmeyer-Haddad K. Phylogenetic analysis of multiple FISH markers in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma suggests that a diverse distribution of copy number changes is associated with poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:98–109. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Killian J.K., Miettinen M., Walker R.L., Wang Y., Zhu Y.J., Waterfall J.J., Noyes N., Retnakumar P., Yang Z., Smith W.I., Jr., Killian M.S., Lau C.C., Pineda M., Walling J., Stevenson H., Smith C., Wang Z., Lasota J., Kim S.Y., Boikos S.A., Helman L.J., Meltzer P.S. Recurrent epimutation of SDHC in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:268ra177. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsch D., Wangsa D., Zhu Y.J., Hu Y., Edelman D.C., Meltzer P.S., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Ott C., Kienle P., Galata C., Horisberger K., Ried T., Gaiser T. Dynamics of genome alterations in Crohn's disease-associated colorectal carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4997–5011. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., DePristo M.A. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X., Wu C., Li C., Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v3.0: a one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:235–241. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherry S.T., Ward M.H., Kholodov M., Baker J., Phan L., Smigielski E.M., Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karczewski K.J., Weisburd B., Thomas B., Solomonson M., Ruderfer D.M., Kavanagh D., Hamamsy T., Lek M., Samocha K.E., Cummings B.B., Birnbaum D., The Exome Aggregation Consortium. Daly M.J., MacArthur D.G. The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D840–D845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tate J.G., Bamford S., Jubb H.C., Sondka Z., Beare D.M., Bindal N., Boutselakis H., Cole C.G., Creatore C., Dawson E., Fish P., Harsha B., Hathaway C., Jupe S.C., Kok C.Y., Noble K., Ponting L., Ramshaw C.C., Rye C.E., Speedy H.E., Stefancsik R., Thompson S.L., Wang S., Ward S., Campbell P.J., Forbes S.A. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941–D947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdottir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciriello G., Cerami E., Sander C., Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Res. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciriello G., Cerami E., Aksoy B.A., Sander C., Schultz N. Using MEMo to discover mutual exclusivity modules in cancer. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2013 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0817s41. Chapter 8:Unit 8.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung M., Chang H.R., Bland K.I., Wanebo H.J. Younger women with breast carcinoma have a poorer prognosis than older women. Cancer. 1996;77:97–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960101)77:1<97::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anastasiadi Z., Lianos G.D., Ignatiadou E., Harissis H.V., Mitsis M. Breast cancer in young women: an overview. Updates Surg. 2017;69:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s13304-017-0424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lischka A., Doberstein N., Freitag-Wolf S., Koçak A., Gemoll T., Heselmeyer-Haddad K., Ried T., Auer G., Habermann J.K. Genome instability profiles predict disease outcome in a cohort of 4,003 breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0566. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anbazhagan R., Fujii H., Gabrielson E. Allelic loss of chromosomal arm 8p in breast cancer progression. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:815–819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yaremko M.L., Recant W.M., Westbrook C.A. Loss of heterozygosity from the short arm of chromosome 8 is an early event in breast cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;13:186–191. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870130308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rummukainen J., Kytola S., Karhu R., Farnebo F., Larsson C., Isola J.J. Aberrations of chromosome 8 in 16 breast cancer cell lines by comparative genomic hybridization, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and spectral karyotyping. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;126:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mertens F., Johansson B., Mitelman F. Isochromosomes in neoplasia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;10:221–230. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aaltonen K., Amini R.M., Landberg G., Eerola H., Aittomaki K., Heikkila P., Nevanlinna H., Blomqvist C. Cyclin D1 expression is associated with poor prognostic features in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy P.G., Pratt N., Purdie C.A., Baker L., Ashfield A., Quinlan P., Thompson A.M. High CCND1 amplification identifies a group of poor prognosis women with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:355–360. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Climent J., Dimitrow P., Fridlyand J., Palacios J., Siebert R., Albertson D.G., Gray J.W., Pinkel D., Lluch A., Martinez-Climent J.A. Deletion of chromosome 11q predicts response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:818–826. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kerangueven F., Eisinger F., Noguchi T., Allione F., Wargniez V., Eng C., Padberg G., Theillet C., Jacquemier J., Longy M., Sobol H., Birnbaum D. Loss of heterozygosity in human breast carcinomas in the ataxia telangiectasia, Cowden disease and BRCA1 gene regions. Oncogene. 1997;14:339–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bielski C.M., Zehir A., Penson A.V., Donoghue M.T.A., Chatila W., Armenia J., Chang M.T., Schram A.M., Jonsson P., Bandlamudi C., Razavi P., Iyer G., Robson M.E., Stadler Z.K., Schultz N., Baselga J., Solit D.B., Hyman D.M., Berger M.F., Taylor B.S. Genome doubling shapes the evolution and prognosis of advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1189–1195. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0165-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blegen H., Will J.S., Ghadimi B.M., Nash H.P., Zetterberg A., Auer G., Ried T. DNA amplifications and aneuploidy, high proliferative activity and impaired cell cycle control characterize breast carcinomas with poor prognosis. Anal Cell Pathol. 2003;25:103–114. doi: 10.1155/2003/491362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multiplex interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (miFISH) results and image cytometry for all cases with the exception of A6, A14, B3, and B15, which are shown in the main body of the manuscript (Figure 2, A and E, and Figure 3, A and E). Color display of miFISH analysis with eight gene-specific probes. Copy number counts for each nucleus are displayed as gains (green), amplifications (dark green), losses (red), and neutral (blue). Markers are plotted horizontally with the Locus column depicting the specific chromosome arm for each probe on the left of the plot, and the corresponding gene name on the right. Nuclei are plotted vertically by pattern frequency. Each vertical line discerns specific gain and loss patterns and the prevalence of these clones in the population. The Gain and Loss columns refer to the percentages of nuclei in which a gain or loss was observed. Color-labeled percentages indicate a 15% threshold of gain or loss. The instability index and the mean ploidy were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Histograms of the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content, when available, are shown below the color displays of the respective cases. The DNA histograms show the quantitative measurements of the nuclear DNA content (x axis) of the tumor cells given in c units. Based on the 2c stemline, the percentages of cells in the G1, S-phase and exceeding the G2/M phase of the cell cycle are determined. The parentheses visualize the area of the corresponding cells in the G2/M phase. The y axis represents the total cell count: between 100 and 200 tumor cells were measured per case.

A and B: Lolliplot chart of the mutation sites in PIK3CA (A) and TP53 (B). A: Mutations are mapped on the linear protein and its domains from the Protein family database (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute; lollipop plot). The different domains of PIK3CA are marked in color: TP53 transactivation motif (5 to 29) in green, TP53 DNA binding domain (95 to 289) in red, and TP53 tetramerization motif (319 to 358) in blue. PI3-kinase family, p85-binding domain (32 to 108) in green; PI3-kinase family, Ras-binding domain (174 to 291) in red; phosphoinositide 3-kinase C2 (351 to 483) in blue; phosphoinositide 3-kinase family, accessory domain (PIK domain) (520 to 703) in yellow; and phosphatidylinositol 3- and 4-kinase (798 to 1014) in purple. Lollipops: green, missense mutation; black, truncating mutation. B: Mutations are mapped on the linear protein and its domains from the Protein family database. The different domains of TP53 are marked in color: TP53 transactivation motif (5 to 29) in green, TP53 DNA binding domain (95 to 289) in red, and TP53 tetramerization motif (319 to 358) in blue. Lollipops: green, missense mutation; black, truncating mutation.