Highlights

-

•

We study the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) using an event-study method.

-

•

Some UK soft-drink stocks were affected negatively by the SDIL announcement.

-

•

Cross sectional analysis shows these negative stock returns were short-lived.

-

•

The financial impact of the SDIL might not be as substantial as portrayed.

Keywords: Soda tax, Industry levy, Event study, Soft-drinks, Tax impact, Stock return

Abstract

On 16th March 2016, the government of the United Kingdom announced the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), under which UK soft-drink manufacturers were to be taxed according to the volume of products with added sugar they produced or imported. We use ‘event study’ methodology to assess the likely financial effect of the SDIL on parts of the soft drinks industry, using stock returns of four UK-operating soft-drink firms listed on the London Stock Exchange. We found that three of the four firms experienced negative abnormal stock returns on the day of announcement. A cross-sectional analysis revealed that the cumulative abnormal returns of soft drink stocks were not significantly less than that of other food and drinks-related stocks beyond the day of the SDIL announcement. Our findings suggest that the SDIL announcement was initially perceived as detrimental news by the market but negative stock returns were short-lived, indicating a lack of major concerns for industry. There was limited evidence of a negative stock market reaction to the two subsequent announcements: release of draft legislation on 5th December 2016, and confirmation of the tax rates on 8th March 2017.

1. Introduction

On 16th March 2016, the UK government announced the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL). Under the SDIL, soft drinks manufacturers were to be taxed according to the volume of products with added sugar they produced or imported, with proceeds used to increase funding for initiatives in schools and other activities to promote child health (House of Commons, 2017). The SDIL explicitly aimed to bring about changes in the behaviour of soft drinks companies, specifically to reformulate their products to reduce sugar content as there were three bands – a zero rate for those with total sugar content lower than 5 g per 100 ml, one rate for those with 5−8 g per 100 ml and a higher rate for drinks with more than 8 g per 100 ml. Drinks classed as pure fruit juices, milk-based drinks, and those containing more than 0.5 % alcohol by volume were exempt. Companies were given two years before the SDIL was enforced to achieve such changes. The draft of the SDIL legislation and consultation summary were released on 5th December 2016. The levy rates were confirmed on 8th March 2017.

The initial announcement of the SDIL came largely as a surprise to the soft-drink industry as the UK government had previously explicitly ruled out a sugar tax in October 2015 (The Independent, 2015). It was met by a negative response from industry, with claims that it would ‘damage thousands of businesses across the entire soft-drink supply chain’ (The Independent, 2016). A modelling study from an economic consultancy quickly followed that suggested that the SDIL would result in more than 4000 job losses across the UK and, together with lower sales, this would reduce GDP by £132 million (Oxford Economics, 2016).

To assess some of the economic effects of the SDIL, this study examined how the stock market reacted, as a representation of investor perceptions of the future profitability of the soft drink firms in the UK. We conducted a study of UK-based firms with a primary focus on soft-drink manufacturing that are quoted on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), to investigate the extent to which SDIL-related announcements caused the actual returns of UK soft-drink stocks to deviate from their benchmark level. In other words, whether these events contributed to negative excess (abnormal) stock returns. To do this, we used an ‘event study’, an approach which has been used to analyse market reactions to other non-financial events, such as regulatory announcements (Larcker et al., 2011; Zhang, 2007), outbreaks of animal disease (Jin and Kim, 2008; Pendell and Cho, 2013) or food recalls (Pozo and Schroeder, 2016; Mazzocchi et al., 2009). We also conducted a cross-sectional analysis to compare stock returns of soft drink firms with that of distiller and vintners, food producers and food retailers in response to the SDIL events. The findings of this study provide important insights into the financial impacts of the SDIL on soft-drink firms.

2. Methods

In an efficient capital market, stock price reflects the expected value of a firm after new information is received and processed by market participants (Malkiel, 2003). Relying on this notion of market efficiency, an event study allows us to examine the impact of the SDIL announcements (i.e. event) on the value of soft-drink firms while accounting for changes in the overall economic environment. If these announcements are found to have generated significant negative (positive) abnormal returns, this reflects a view by the market of a negative (positive) impact of SDIL on company profitability. Abnormal returns (AR) are defined as the difference between the actual returns of a stock and its normal returns that would be expected if the event did not occur. Given the SDIL was an unexpected action by the Government for the market, the event study can provide an accurate initial market reaction to the news and therefore on how the markets expected this measure to affect the soft-drink industry.1

2.1. Events

The key event of interest is the announcement of the SDIL by the UK government in the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s Spring Budget Statement on 16th March 2016. It was announced that the Levy would have three bands; zero at total added sugar content of less than 5 mg per 100 ml; some positive levy for soft drinks over 5 g per 100 ml; and a higher levy for those with total sugar content of more than 8 g per 100 ml. With this structure, the SDIL was designed to incentivise drink firms to reformulate their products to include less added sugar and so move consumers toward lower sugar alternatives. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the levy was expected to raise £520million in its first year. The Chancellor did not announce the tax rates, but this revenue estimate led to various speculations. In addition, the details of how SDIL would be implemented were at that point yet to be confirmed.

There were two subsequent announcements. First, the release of draft SDIL legislation and consultation summary on 5th December 2016. This confirmed the band system. The consultation summary indicated that 95 % of medical and health bodies who responded were supportive of the proposals, as well as 73 % of food and beverage retailers (HM Treasury, 2016). A majority (78 %) of manufacturers and associated trade bodies were opposed to the levy.

Second, announcement of the SDIL rates on 8th March 2017. These were set at £0.18 per litre for drinks with between 5 g and 7.99 g per 100 ml, £0.24 per litre for those with more than 8 g per 100 ml. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility revised estimates, the tax was now expected to raise £400 million a year; £120million less than announced in March 2016 (Financial Times, 2017).

The SDIL came into effect on 6th April 2018. As it was announced by the UK government in advance, the implementation of SDIL on this day was not an unexpected shock to the market and therefore would not have caused changes in the stock market value of the soft drink firms. This absence of stock market response is confirmed in the supplementary analysis provided in the appendix. In this regard, we did not include the SDIL implementation as an event in the main analysis.

2.2. Event and estimation windows

The event window is the period over which we study the market response to the event. Apart from the day of event, the event window includes days after the event to avoid the potential bias due to delays in the market reaction to the new information. It is also common practise to include days before the event to account for the possibility that the market may anticipate the event. However, as the chances of biases from confounding events increase with the length of event window, it is crucial that the event window is as short as possible to minimise the effect of other events whilst being long enough to account for the possibility that some stocks are thinly traded and to ensure the dissemination of information regarding the event (Swaminathan and Moorman, 2009). Several newspapers reported strong opposition from the soft drink industry on the day after the announcement. There was also a very brief mention of legal action against the levy (Penney et al., 2018). These industry responses might have an impact on the investors’ expectation on the effect of the SDIL. We denote the day of the event as day 0 and use to represent the event window, where and are the start and end dates of the window respectively.

The estimation window, , is the period over which we estimate how a stock normally relates to the market, which starts from day and ends on day with . The estimation window is mutually exclusive with the event window so as to avoid possible influence from the event of interest on the normal return parameter estimates. Following MacKinlay (1997), a 120 trading day estimation window is used that begins before the event window; and . Fig. 1 demonstrates the timeline for an event study in which event window is , and the corresponding estimation window is . Considering that there is limited theory pertaining to the appropriate selection of the event window, this paper examines the stock returns of UK soft drink firms over different lengths of event window (i.e. ,, and ) so as to ensure the full stock market effect of the SDIL is captured.

Fig. 1.

Estimation and event windows.

Note: Number of days away from the event day (t) is given in parentheses.

2.3. Abnormal stock returns

Stock investments generate capital gains from increases in equity prices as well as dividend payments. Following Henderson (1990), we calculated log transformed daily returns of a stock as follow:

| (1) |

is the actual return of stock at day . and are the price of stock at day and day -1 respectively. gives the dividends paid at day . By multiplying with 100, could also be interpreted as percentage return of stock investment.

The impact of an event on the value of a firm is measured by the sum of daily abnormal stocks returns within the event window. It is computed as follows:

| (2) |

is therefore the actual ex post return of stock minus its expected (normal) return at day . To reassure our results are not biased by spurious regressions, we conducted the Augmented Dickey-Full test below to check if the time series of stock returns are stationary. The presence of unit roots is rejected in all return series (Appendix A).

A market return model is used to identify the ordinary behaviour of the stock return and hence estimate . This method has two advantages over the constant mean return model, another commonly used estimation method of normal stock return (Henson and Mazzocchi, 2002). First, it removes the part of the return on stocks that is related to variations in market returns, which in turn generally leads to greater sensitivity to the effects of specific events. Second, the market model is suggested to have smaller variance of abnormal residuals, resulting in more reliable statistical tests. The market return model is the following:

| (3) |

where is the log-transformed return of a market portfolio at day and is the normally distributed residual. We estimate Eq. 2 with ordinary least squares (OLS) using a subset of the data within the estimation window .

Using the beta ( estimates from Eq. 2, the normal return of each stock is computed as:

| (4) |

Substituting this back into Eq. 1 we can estimate the abnormal returns, which corresponds to the residual in Eq. 2:

| (5) |

The financial impact of an event on firm is captured by its cumulative abnormal return (CAR) within the entire event window, which is given by:

| (6) |

where is the number of days within the event window.

A number of parametric tests, such as Patell Standardised Residuals test (Patell, 1976), have been developed to assess the statistical significance of AR. These testing procedures are, however, based on the assumption that ARs are normally distributed. Early studies showed that this assumption normally does not hold for AR on a single day (e.g. Brown and Warner, 1985; Bollerslev et al., 1992; Masse et al., 2000). Considering that we were interested in whether the SDIL events caused significant deviation of stock returns on the day of the events, we adopted instead the nonparametric generalized rank (GRANK) test proposed by Kolari and Pynnonen (2011). This test is distribution free and thus more appropriate than parametric tests if there are non-normalities in the distribution of AR.2 It also has better empirical power on testing CARs over other existing tests (Kolari and Pynnonen, 2011). All statistical analyses were done in STATA in which the “estudy” command written by Pacicco et al. (2018) was used to estimate the ARs, CARs and the GRANK test statistics.

2.4. Data

The UK soft drinks industry is composed of a few branded manufacturers and some private label producers. We selected companies which are quoted on the LSE under beverage sector. Among the eight firms quoted, three are alcoholic beverage manufacturers (i.e. Diageo, Distil and Stock Spirit), which are therefore excluded from the main analysis. In March 2016, Coca Cola business in the UK was operated by Coca Cola Enterprises which is not considered here as it was listed on New York Stock Exchange and thus not comparable with other firms.3 Our analysis thus focuses on the four remaining companies operating in the UK affected by the SDIL: A. G. Barr Plc, Britvic Plc, Fever-Tree Drinks Plc and Nichols Plc.4 Based on Euromonitor International data (2019), these firms comprise 15.4 % of the UK “soft-drinks” market in 2017, which also includes other drinks, such as bottled water, juices and ready-to-drink teas and coffees. Over 50 % of the portfolios of the four firms were likely to be affected by the SDIL (Table 1). While not representative of the full soft-drink market, the analysis of these four companies nonetheless provides an interesting case study to investigate the industry effects of the government policy.

Table 1.

Approximate proportion of portfolio affected by the SDIL.

| Approximate proportion of portfolio affected by the SDIL | Sources | Drinks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. G. Barr Plc | 60 % | A. G. Barr Plc’s annual report in 2016 | Iru-Bru, Snapple, Rubicon |

| Britvic Plc | 66 % | Britvic Plc’s annual report in 2016 | Pepsi, Robinsons, Tango, 7up |

| Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | 75 % | Analysts’ estimate obtained from Reuters, 2016) | Tonic Water, Lemonade |

| Nichols Plc | 64 % | British Soft Drinks Association (2015) | Vimto, Sunkist |

Table 2provides financial information on the four firms. Based on total revenue, Britvic Plc is the largest UK soft-drink firm listed on the LSE, followed by A. G. Barr Plc. Fever-Tree Drinks Plc has experienced the fastest growth in terms of total revenue and net income from 2015 to 2017. A. G. Barr Plc and Nichols Plc focus their business relatively more in the UK with 96 % and 81 % of their revenue from this market respectively. In 2018, while the UK became a relatively more important market for Fever-Tree Drinks Plc, where its percentage of revenue from the UK increased by 22 % from 2015, the UK share of Britvic Plc’s revenue decreased to 63 % from 68 % in 2015.

Table 2.

Financial information of UK soft-drink firms listed on the LSE†.

| Financial year | Ending date of financial year | Total revenue | Net Income | Geographical revenue distribution |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (in ‘000 GBP) | (in ‘000 GBP) | UK (%) | non-UK (%) | ||

| A. G. Barr Plc (Ticker: BAG.L) | |||||

| 2015 | 30/01/2016 | 258,600 | 34,300 | 96 | 4 |

| 2018 | 26/01/2019 | 279,000 | 35,800 | 96 | 4 |

| Britvic Plc (Ticker: BVIC.L) | |||||

| 2015 | 27/09/2015 | 1,300,100 | 103,800 | 68 | 32 |

| 2018 | 30/09/2018 | 1,503,600 | 117,100 | 63 | 37 |

| Fever-Tree Drinks Plc (Ticker: FEVR.L) | |||||

| 2015 | 31/12/2015 | 59,253 | 13,331 | 35 | 65 |

| 2018 | 31/12/2018 | 237,449 | 61,779 | 57 | 43 |

| Nichols Plc (Ticker: NICL.L) | |||||

| 2015 | 31/12/2015 | 109,279 | 22,233 | 78 | 22 |

| 2018 | 31/12/2018 | 142,037 | 25,515 | 81 | 19 |

Sources: Annual reports from corresponding soft-drink firms. †Examples of soft drinks produced by these companies are given in the appendix. §Estimated by analysts given in Reuters (2016). ‡(British Soft Drinks Association, 2015).

The Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 250 Index was used to capture market return in the UK. This enabled us to account for changes in the overall economic environment in the UK that affects the stock market. It is a value-weighted share index of the 101st to the 350th largest companies listed on the LSE. Compared to the FTSE 100 index, consisting of the largest 100 firms listed on the LSE, FTSE250 has less internationally focused companies which predominately derive their income from the UK economy. It is thus a better indicator of the UK economic performance. We used Yahoo!Finance to obtain data on dividends and closing stock prices of the firms as well as the market indices. We also checked the robustness of our findings by using FTSE All Share Index as the market return, which represents 98–99 % of UK market capitalisation (FTSE Russell, 2019).

Fig. 2 illustrates stock prices of the four soft drink firms available for the analysis from July 2015 to July 2018. Consistent with its rapid increase in revenue, the market value of Fever-Tree Drinks Plc displayed the fastest growth rate. Its stock price increased fivefold over three years. From the descriptive assessment, the SDIL-related announcements do not seem to have had a strong effect on the trends of stock prices of UK soft-drink firms listed on the LSE. It can also be seen that the UK stock market has been improving since the late 2016 as suggested by the upward trend of FTSE250 index in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Prices of UK soft drink stocks listed on the LSE (in GBP), July 2015 - July 2018.

Note: Blue lines indicate the day of SDIL announcement (16th March 2016). Green lines indicate the day when the SDIL draft legislation and consultation report were published (5th December 2016). Red lines indicate the day when SDIL rates were confirmed (8th March 2017). Orange lines indicate the day when the SDIL was implemented (6th April 2018)

Fig. 3.

FTSE250 Index, March 2015 - July 2018.

Note: Blue line indicates the day of SDIL announcement (16th March 2016). Green line indicates the day when the SDIL draft legislation and consultation report were published (5th December 2016). Red line indicates the day when SDIL rates were confirmed (8th March 2017). Orange line indicates the day when the SDIL was implemented (6th April 2018)

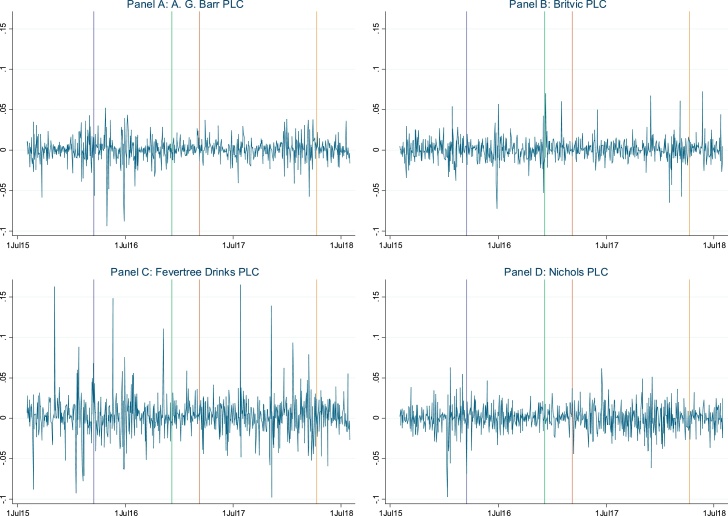

Similarly, Fig. 4 displays limited evidence of a strong SDIL impact on the daily actual return of soft drink stock. While the daily return of all four firms bounced around zero over the data period, Fever-Tree Drinks Plc was shown to have the most volatile stock returns. The volatility of these firms did not show obvious changes after each SDIL event.

Fig. 4.

Daily actual returns of UK soft drink stocks listed on LSE (in GBP), July 2015 - July 2018.

Note: Blue line indicates the day of SDIL announcement (16th March 2016). Green line indicates the day when the SDIL draft legislation and consultation report were published (5th December 2016). Red line indicates the day when SDIL rates were confirmed (8th March 2017). Orange line indicates the day when the SDIL was implemented (6th April 2018)

3. Results

This section first reports the results for the announcement of the SDIL which was recognised as a shock to the industry. It then discusses the findings for the two subsequent SDIL-related events. All ARs and CARs were estimated with FTSE 250 as the market index. As robustness check, we repeated the analysis with FTSE All Share Index and reported the estimates in the appendix B. We also used the estimates from a longer estimation window 250 days in appendix C.

3.1. Announcement of the SDIL - 16th march 2016

Fig. 5 shows the daily abnormal stock returns to the UK soft drink firms over an 11-day event window, . Data points labelled with markers are statistically significant at the 5 % level. The magnitude of the market response is further illustrated in Table 3, presenting CARs computed using different length of event windows. With a 1-day event window, the CAR is equivalent to the daily abnormal return on the day of announcement. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that, on the day of announcement (day 0), most listed UK soft drink firms experienced a significant decline in their abnormal stock returns with the exception of Fever-Tree Drinks Plc. Nichols Plc is found to have faced the largest drop in stock returns relative to its benchmark level on the day of the initial SDIL announcement abnormal return (-0.071 in Table 3), followed by A. G. Barr Plc (-0.028) and Britvic Plc (-0.021).

Fig. 5.

Daily abnormal returns in response to SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016.

Note: Statistically significant abnormal returns at 5 % level are labelled with markers based on GRANK test statistics.

Table 3.

CARs for the announcement of SDIL on 16th March 2016.

| Event window | A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.028** | −0.021** | −0.015 | −0.071*** |

| (2.206) | (2.238) | (0.559) | (3.883) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.079*** | −0.044*** | 0.067 | −0.095*** |

| (3.580) | (2.685) | (1.473) | (2.934) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.074** | −0.030 | 0.117 | −0.086** |

| (2.534) | (1.380) | (1.996) | (2.024) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.069* | −0.033 | 0.160** | −0.104** |

| (1.966) | (1.303) | (2.288) | (2.039) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.051 | −0.030 | 0.179** | −0.103* |

| (1.277) | (1.039) | (2.239) | (1.772) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.041 | −0.017 | 0.185** | −0.093 |

| (0.915) | (0.516) | (2.083) | (1.440) |

Note: GRANK test statistics are given in parenthesis. ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

As the market response to an event may spread over time it is important to consider abnormal returns over the entire event window. Both A. G. Barr Plc and Britvic Plc continued to display a statistically significant and negative abnormal return on the day after the announcement (day 1) in Fig. 5. By day 2, the daily return of soft-drink stocks returned to their normal level with no statistical difference from zero. The CARs of A. G. Barr Plc and Britvic Plc were negative in a 3-day event window with the magnitude of 0.079 and 0.044 respectively, which decreased over longer horizon (Table 3). Among all four firms, Nichols Plc appeared to be most affected by the SDIL announcement as it was the only firm recorded the statistically significant negative CARs at a rate of 0.103 in a 9 day event window. The positive CARs of Fever-Tree Drinks Plc over longer event windows were likely to be due to its announcement of an 82 per cent jump in full-year profit on 14th March 2016 (Fever-Tree Drinks Plc, 2016). The negative CARs of the other three firms suggest that investors reacted almost immediately to the announcement of SDIL and regarded it negatively and also that it would have a larger impact on Nichols Plc, followed by A. G. Barr Plc and Britvic Plc.5

3.2. Subsequent SDIL - related announcements – 5th december 2016 & 8th march 2017

Turning to the two subsequent SDIL events, Table 4 demonstrates that none of the firms were affected negatively by these events. The negative abnormal stock return on day 0 for the release of consultation report events was found (but not statistically significant different from zero) for all firms. The market reaction remained minimal even after extending the event window except for Britvic Plc. Its CARs were statistically significant and varied from -0.051 to 0.069. This mixed market reaction could be due to its announcement of 10.3 % growth in profit after tax on 30th November 2016 (Britvic Plc, 2016) and the investment rating downgrading by Goldman Sachs on 2nd December 2016 (Investegate, 2016).

Table 4.

CARs (%) to subsequent SDIL announcements.

| Event window | A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Release of SDIL consultation report on 5th December 2016 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.005 | −0.009 | −0.010 | 0.005 |

| (0.400) | (0.945) | (0.552) | (0.407) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.002 | −0.027* | −0.017 | 0.017 |

| (0.094) | (1.732) | (0.508) | (0.865) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.029 | −0.051** | −0.068 | 0.015 |

| (0.937) | (2.514) | (1.580) | (0.576) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.036 | 0.062** | −0.043 | −0.009 |

| (0.989) | (2.535) | (0.831) | (0.313) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.025 | 0.060** | −0.025 | 0.008 |

| (0.586) | (2.135) | (0.427) | (0.229) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.003 | 0.069** | −0.021 | 0.013 |

| (0.064) | (2.231) | (0.324) | (0.329) | |

| Panel B: Confirmation of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.014 | −0.010 | −0.008 | 0.036*** |

| (1.466) | (0.760) | (0.458) | (3.876) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.057*** |

| (1.466) | (0.760) | (0.458) | (3.876) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.003 | −0.004 | 0.008 | 0.074*** |

| (0.113) | (0.144) | (0.221) | (3.490) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | 0.017 | −0.006 | 0.029 | 0.033 |

| (0.639) | (0.167) | (0.638) | (1.283) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | 0.044 | 0.002 | 0.016 | 0.048 |

| (1.433) | (0.040) | (0.309) | (1.639) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | 0.064 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.065* |

| (1.908) | (0.022) | (0.356) | (1.968) | |

Note: GRANK test statistics are given in parenthesis. ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

Similarly, the confirmation of SDIL rates did not appear to have a negative impact on returns of soft drink stocks. This suggests that this event did not reveal SDIL-related information that was unexpected by the market. Indeed, although the tax rates were not announced by the government on 16th March 2016, they were speculated to be around 18p to 24p per litre based on the revenue estimates even though this was not confirmed until 8 March 2017 (Beverage Daily, 2016a,b). One exception was the stock returns of Nichols Plc which experienced a positive CAR for SDIL rate confirmation on 8th March 2017. These positive stock returns ranged from 0.036 to 0.076 depending of the length of event window considered, suggesting the existence of confounding events which contributed to a positive outlook of Nichols Plc despite the SDIL event.6 The estimates in Table 3, Table 4 were robust to the case in which the normal behaviour of soft drink stocks was modelled with a 250-day estimation window. Overall, the stock market did not regard subsequent SDIL announcements as presenting risk of further harm to soft drink firms’ profitability.

4. Cross-sectional analysis

Since the SDIL was announced on 16th March 2016 as part of the Budget by the Government, the negative stock market reaction shown in Table 3 might not be unique to soft drink firms. There could be other policies that may have a negative impact on food and drinks related companies and hence not well captured by the market return index. To verify, we extended the above event study analysis to UK-operating firms listed on the LSE under the sectors of distillers and vintners, food retailers and food producers. We first estimated their CARs for these stocks for each SDIL event and then pooled these estimates together with the ones given in Table 3, Table 4 for a cross-sectional regression (MacKinlay, 1997). The aim of this analysis is to indicate if the CARs of soft drink firms were significantly different from that of other food and drinks related firms.

To limit the influence from confounding events, we focused our discussion on the ARs on the event day () and the CARs of a 3 day event window ()7, which are given in Table 5. Most firms did not experience a statistically significant AR on the day of SDIL announcement except for Finsbury Food Group Plc and Purecircle Ltd. These two firms recorded positive abnormal returns of 0.047 and 0.066 respectively, suggesting that the investors expected a more favourable business environment for them. The Finsbury Food Group Plc is a speciality bakery manufacturer, producing a wide range of cake, bread and snack products for retailers and food service channels. While in principle some substitution from soft drinks to sweet bakery products might occur, the SDIL is unlikely the key driver behind its positive AR due to its diverse product mix. However, the association with SDIL and positive AR for Purecircle Ltd which is a manufacturer of artificial sweeteners is more likely. The SDIL explicitly gave an incentive to reformulate soft drink recipes to contain less sugar for which one possibility is to replace caloric added sugar with low- or no-calorie sweeteners, which would create greater demand for products manufactured by Purecircle Ltd. In addition, Ocado Group Plc experienced a positive CARs over the 3-day event window, which could be due to its confounding announcement of 15 % sales growth in the first quarter of 2016 (Ocado Group Plc, 2016).

Table 5.

ARs/ CARs of other food and drinks related firms in response to SDIL- related events.

| Firms | SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016 |

Release of consultation report on 5th December 2016 |

Confirmation of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day (0,0) | 3 days (-1,1) | 1 day (0,0) | 3 days (-1,1) | 1 day (0,0) | 3 days (-1,1) | |

| Distillers & Vintners | ||||||

| C&C Group Plc | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.011 | 0.025 | −0.006 | −0.003 |

| Diageo Plc | −0.003 | −0.016 | 0.001 | −0.007 | −0.001 | −0.003 |

| Distil Plc | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.016 | 0.080 |

| Stock Spirits Group Plc | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.008 | −0.013 | 0.017 | −0.020 |

| Food producers | ||||||

| Associated British Foods Plc | −0.002 | −0.008 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.019 |

| Cranswick Plc | 0.014 | 0.047 | −0.023 | −0.015 | −0.001 | −0.008 |

| Devro Plc | −0.001 | −0.023 | 0.036 | 0.128 | 0.020 | 0.002 |

| Finsbury Food Group Plc | 0.047 | −0.010 | 0.004 | −0.008 | 0.000 | −0.019 |

| Glanbia Plc | −0.017 | −0.016 | −0.012 | −0.012 | 0.000 | 0.031 |

| Greencore Group Plc | −0.002 | −0.011 | 0.007 | −0.020 | −0.010 | −0.014 |

| Hilton Food Group Plc | 0.007 | −0.010 | −0.006 | 0.035 | −0.004 | 0.029 |

| Kerry Group Plc | −0.006 | 0.001 | −0.011 | 0.004 | 0.006 | −0.003 |

| Premier Foods Plc | 0.004 | −0.021 | −0.001 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Purecircle Ltd | 0.066 | 0.081 | −0.012 | −0.090 | −0.032 | 0.030 |

| Real Good Food Plc | −0.002 | −0.011 | −0.001 | −0.084 | 0.000 | −0.014 |

| Science In Sport Plc | 0.002 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.009 | −0.014 | −0.076 |

| Tate & Lyle Plc | −0.015 | −0.028 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| Unilever Plc | −0.015 | −0.015 | 0.004 | 0.012 | −0.005 | 0.030 |

| Food retailers | ||||||

| Greggs Plc | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.005 | −0.004 |

| Mccoll's Retail Group Plc | 0.019 | 0.038 | 0.008 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.053 |

| Wm Morrison Supermarkets Plc | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.003 | −0.073 |

| Ocado Group Plc | 0.043 | 0.120 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.014 | 0.001 |

| J Sainsbury Plc | −0.002 | −0.012 | 0.010 | 0.029 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| SSP Group Plc | −0.003 | 0.012 | −0.004 | −0.021 | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| Tesco Plc | −0.007 | −0.015 | 0.024 | 0.020 | −0.006 | −0.023 |

| Total Produce Plc | −0.003 | 0.027 | −0.001 | −0.013 | −0.002 | −0.004 |

Note: Statistically significant abnormal returns at 5 % level are marked in bold based on GRANK test statistics.

For the subsequent events, while significant ARs and CARs were not found for most firms, Devro Plc, a sausage casting producer, recorded a 0.128 CARs over the 3 day event window of the release of consultation report on 5th December 2016 and Wm Morrison Supermarket Plc faced a -0.073 CARs over the 3-day event window of the confirmation of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017. These CARs were likely to be driven by confounding events rather than SDIL events as their ARs on the day of SDIL event were not statistically significant.

To carry out the cross-sectional analysis, for each event, we pooled the CAR estimates in Table 3, Table 5 and estimated the following equation:

where indicates the estimates of abnormal returns of each stock c given in Table 1, Table 6 and is the constant term. is a dummy indicator which takes the value of 1 if the stock belongs to soft drink sector (i.e. one of the firms listed on Table 2) and 0 otherwise. is the logarithm of market capitalisation (i.e. total value of a company) of the prior month, obtained from the LSE database8 . For instance, for the SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016, market capitalisation in February 2016 was used. This variable serves as proxy variable for firm size, which is a firm characteristic commonly used as a control in cross-sectional analysis of stock returns (e.g. Pozo and Schroeder, 2016; Devos et al., 2015; Lopatta and Kaspereit, 2014). In addition, it is also a potential determinant of the reduction in food company valuation caused by an event (Salin and Hooker, 2001).

Table 6.

Cross-sectional analysis of CARs.

| 1 day (0,0) | 3 days (-1,1) | 5 day (-2,2) | 7 days (-3,3) | 9 day (-4,4) | 11 days (-5,5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Panel A: Announcement of SDIL on 16th March 2016 | ||||||

| Soft drinks | −0.043*** | −0.045 | −0.025 | −0.031 | −0.025 | −0.042 |

| (0.013) | (0.034) | (0.043) | (0.055) | (0.058) | (0.060) | |

| Firm size | −0.004*** | −0.002 | −0.004* | −0.014** | −0.016*** | −0.018*** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | 0.100*** | 0.050 | 0.098* | 0.297** | 0.341*** | 0.423*** |

| (0.033) | (0.034) | (0.049) | (0.108) | (0.097) | (0.152) | |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R-squared | 0.443 | 0.146 | 0.064 | 0.249 | 0.244 | 0.137 |

| Panel B: Release of SDIL consultation report on 5th December 2016 | ||||||

| Soft drinks | −0.008* | −0.010 | −0.033* | −0.003 | −0.009 | 0.002 |

| (0.004) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| Firm size | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | 0.000 | −0.043 | −0.023 | −0.059 | −0.001 | 0.028 |

| (0.017) | (0.074) | (0.086) | (0.079) | (0.113) | (0.107) | |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R-squared | 0.053 | 0.024 | 0.083 | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| Panel C: Confirmations of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 | ||||||

| Soft drinks | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.022 |

| (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.020) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.019) | |

| Firm size | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.004 | −0.008 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | −0.014 | 0.031 | 0.095 | 0.184 | 0.086 | 0.087 |

| (0.017) | (0.093) | (0.161) | (0.213) | (0.158) | (0.159) | |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R-squared | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.085 | 0.025 | 0.033 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Panel A of Table 6 reports the OLS estimates of the cross-sectional regressions over different event windows for the announcement of SDIL. On the event day, the ARs of soft drink firms were found to be significantly lower than other firms at a magnitude of 0.043. This association was no longer statistically significant over longer horizons. Firm size was found to be generally an important factor in explaining the magnitude of CARs. Panel B gives the cross-sectional results for the release of SDIL consultation report on 5th December. Column 1 shows some weak evidence that AR of soft drink firms was slightly lower (0.008) than other firms on the day of the event. This association was also observed over a 5-day event window (column 3), which was unlikely to be driven by the SDIL event as it was not statistically significantly different from zero when using a 3- day event windows (columns 2). Similar negative coefficients on soft drink firms were not observed in panel C for the confirmation of soft drink rates on 8th March 2017. This was in line with the argument that as the rates were largely speculated, the confirmation did not provide new information to the investors, leading to no impacts of the stock returns of soft-drink firms. In both panels B and C, firm size was not found to be linked to the CARs.

5. Discussion & conclusion

Using event study method, this study investigated the effect of SDIL-related announcements on the market value of UK soft-drink manufacturer stocks. Our results suggest that investors significantly lowered their valuation of these firms in response to the first SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016, with the exception of Fever-Tree Drinks Plc. Since Nichols Plc experienced the largest negative abnormal stock return, one might infer that its future profitability was perceived to be the most affected of the manufacturers we studied. The heterogeneity of CARs across soft-drink firms appears to be consistent with their different geographical business concentration. Nichols Plc and A. G. Barr Plc, which have higher share of business in the UK, experienced larger negative CARs. Conversely, stock returns of Fever-Tree Drinks Plc were unaffected by the first SDIL announcement. With a smaller share of revenue (40–50 %) generated from the UK, it is not surprising that the market may have perceived the SDIL as a lower threat to Fever-Tree Drinks Plc. In addition, it occupies a different market niche as it is a manufacturer of ‘mixers’; considered a premium product over regular soft-drinks, and thus potentially less vulnerable to increased price through the SDIL.

Across the event windows for the SDIL announcement, significant negative CARs were not observed for UK-operating alcohol, food retail and food producing firms listed on the LSE. The cross-sectional results suggested that the ARs of soft drink stocks were 0.043 lower than that of other food and drinks related stocks on the day of the SDIL announcement. Such difference was no longer statistically significant for CARs estimated with longer event windows. While these results demonstrate that the SDIL announcement was viewed by the stock market as bad news for the soft drink industry, it had limited impacts on other food and drink related industries. Furthermore, the market reaction was less persistent than one found in response to meat and poultry recalls in the US by Pozo and Schroeder (2016). Their result showed that the negative CARs across US meat industry stocks remained statistically significant 20 trading days after recall announcements. Table 4 showed the CARs of the UK soft drinks firms in response to the first SDIL announcement were no longer significant after 4 trading days. There was limited evidence of significantly negative stock market reaction both in terms of ARs and CARs to the release of the SDIL consultation report and the confirmation of the SDIL rates, which was largely consistent with the cross-sectional findings.

One limitation needs to be considered. The analysis excluded private labels or soft drink producers that were not listed on LSE, such as Coca Cola. Considering that we only examined the stock market returns of four UK-operating firms, the present event study does not have sufficient statistical power to detect the presence of non-zero abnormal stock returns across firms (MacKinlay, 1997). Thus, while our results are empirically valid for each individual firm, caution is required in terms of their applicability to the entire soft drink industry.

Overall, the abnormal stock returns in response to the SDIL news we observed were generally negative but short-lived. While the stock market initially perceived the SDIL announcement as detrimental to the soft-drink firms, the ‘bounce-back’ of CARs suggests that negative financial impact might not be as substantial as portrayed by the industry. Indeed, the share prices of all firms studied in this paper displayed a general increasing trend after 2016 (Fig. 1). More importantly, even though A. G. Barr was the company that suffered the largest negative financial shock from the SDIL announcement, its annual net income increased from £34.4million in 2016 to £35.8million in 2018 (Table 1). More broadly, that only four companies comprising 15 % of the market were eligible for inclusion suggests a diffused market with most companies having wide portfolios, or more global coverage, which may make policies such as SDIL relatively insignificant in terms of their material effect and more significant perhaps as rhetorical devices. In this case there needs to be more research on the value of shock announcements and the core drivers of impact from fiscal policy devices, especially over the medium- to long-term.

Author statement

CL, LC, and RS conceptualised the study and were responsible for the study design, development of methods. CL managed the data collection and conducted the literature review for background as well as the data analysis. CL, LC, RS, TP, MW drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

Evaluation of the SDIL is funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research, Public Health Research programme [Grant numbers: 16/49/01 & 16/130/01]. LC is funded by an MRC Fellowship Grant (MR/P021999/1). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the MRC, NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health.

Declaration of Competing Interest

MW is Director of NIHR’s Public Health Research Programme. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Numerous news sources, including industry news, reported the SDIL announcement as a surprise tax. for example, Beverage Daily (2016a,b) reported that “The announcemnet of a levy has come as a surprise to many”. Financial Times (2016)Financial Times described the sugar tax as “something unexpected”. The Guardian (2016) said that “Osborne stunned drinkmakers at the budget by announcing a tax on drinks with added sugar”. See ITV News (2016); Fortune (2016) and The Telegraph (2016) for more examples.

In unreported results, we performed skewness and kurtosis normality test and the Shapiro-Wilk test over the estimated abnormal returns of all firms studied. Most of them were found to be not normally distributed, suggesting that parametric testing methods were not appropriate.

While Coca Cola HBC AG, a major bottler for Coca Cola, is listed on the LSE, it is excluded as it does not operate in the UK and therefore would not be affected by the levy. In unreported results, we tested their stock returns using the same event study method and found no evidence of significant deviation in their stock returns from the normal level during the SDIL-events.

Nichols Plc and Fever-Tree Drinks plc are listed on Alternative Investment Market (AIM) rather than the Main Market of LSE. Shares on AIM tend to have a large gap between the buying and selling price and be more thinly traded.

In the appendix, we performed a supplementary analysis of the implementation of SDIL on 6th April 2018. As the date of implementation was announced by the government well in advance, it is unsurprising that no significant stock market response was found.

While Nichols Plc announced a 15.3% rise in the final dividend on 2nd March 2017 (Nichols Plc, 2017), no further news specific to Nichols Plc was found from 2nd March 2017 to 15th March 2017. A further in-depth research is needed to identify the cause of the positive CARs observed, which is beyond the scope of the current paper.

In unreported results, we estimated the CARs for other lengths of event window. Most CARs estimates were not statistically significant based on the GRANK test statistics. There was no clear pattern of significant CARS across firms or across events.

Appendix A

A. Augmented Dickey-Full test statistics

| A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc | FTSE 250 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z(t) | −10.45 | −12.01 | −9.11 | −12.17 | −10.83 |

Note: The estimates are obtained using stock price data from -125 day to -6 trading day before the initial SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016. They are robust to the case when the data period is extended to 250 trading days before the event window. Test statistics on normal returns of non-soft drink stocks are available upon request.

B. CARs with FTSE All Share index and a 120-day estimation window

| Event window | A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Announcement of SDIL on 16th March 2016 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.026** | −0.018** | −0.012 | −0.070*** |

| (1.997) | (1.824) | (0.434) | (3.806) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.075*** | −0.038** | 0.073 | −0.092*** |

| (3.306) | (2.181) | (1.572) | (2.843) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.067** | −0.019 | 0.129** | −0.081** |

| (2.225) | (0.824) | (2.155) | (1.896) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.061* | −0.023 | 0.173** | −0.099** |

| (1.699) | (0.840) | (2.422) | (1.941) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.044 | −0.019 | 0.191** | −0.097* |

| (1.057) | (0.597) | (2.352) | (1.668) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.037 | −0.012 | 0.191** | −0.091 |

| (0.814) | (0.353) | (2.101) | (1.404) | |

| Panel B: Release of SDIL consultation report on 5th December 2016 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.006 | −0.009 | −0.012 | 0.004 |

| (0.377) | (0.853) | (0.578) | (0.399) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.006 | −0.030 | −0.022 | 0.017 |

| (0.209) | (1.647) | (0.632) | (0.873) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.035 | −0.058** | −0.081 | 0.014 |

| (1.017) | (2.431) | (1.790) | (0.566) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.044 | 0.054* | −0.058 | −0.010 |

| (1.046) | (1.883) | (1.068) | (0.326) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.029 | 0.055* | −0.035 | 0.007 |

| (0.601) | (1.672) | (0.571) | (0.209) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.003 | 0.069* | −0.022 | 0.013 |

| (0.062) | (1.893) | (0.319) | (0.327) | |

| Panel C: Confirmations of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.014 | −0.008 | −0.005 | 0.036*** |

| (1.360) | (0.563) | (0.306) | (3.856) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.008 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.057*** |

| (0.478) | (0.204) | (0.499) | (3.469) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.016 | 0.074*** |

| (0.079) | (0.057) | (0.404) | (3.467) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | 0.018 | −0.001 | 0.035 | 0.033 |

| (0.647) | (0.029) | (0.760) | (1.270) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.048 |

| (1.341) | (0.061) | (0.347) | (1.638) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | 0.068* | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.064* |

| (1.963) | (0.039) | (0.344) | (1.961) | |

Note: GRANK test statistics are given in parentheses. ***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.1 Test statistics for non-soft drink firms are available upon request.

C. CARs estimated with FTSE 250 and a 250-day estimation window

| Event window | A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Announcement of SDIL on 16th March 2016 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.028** | −0.020** | −0.016 | −0.071*** |

| (2.265) | (2.287) | (0.683) | (4.632) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.079*** | −0.041*** | 0.061 | −0.098*** |

| (3.656) | (2.695) | (1.499) | (3.584) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.073** | −0.025 | 0.108** | −0.090** |

| (2.597) | (1.264) | (2.056) | (2.521) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.068** | −0.027 | 0.148** | −0.109** |

| (2.026) | (1.152) | (2.369) | (2.562) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.049 | −0.022 | 0.161** | −0.112** |

| (1.282) | (0.829) | (2.270) | (2.316) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.038 | −0.007 | 0.163** | −0.106* |

| (0.891) | (0.233) | (2.065) | (1.969) | |

| Panel B: Release of SDIL consultation report on 5th December 2016 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.006 | −0.010 | −0.010 | 0.004 |

| (0.369) | (0.984) | (0.423) | (0.260) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.004 | −0.030* | −0.015 | 0.018 |

| (0.133) | (1.782) | (0.377) | (0.609) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.030 | −0.056** | −0.065 | 0.014 |

| (0.930) | (2.105) | (0.616) | (0.233) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | −0.038 | 0.055** | −0.038 | −0.010 |

| (0.930) | (2.105) | (0.616) | (0.233) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | −0.027 | 0.051* | −0.020 | 0.006 |

| (0.581) | (1.703) | (0.275) | (0.126) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | −0.007 | 0.059* | −0.015 | 0.013 |

| (0.139) | (1.786) | (0.190) | (0.239) | |

| Panel C: Confirmations of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 | ||||

| 1 day (0,0) | −0.015 | −0.009 | −0.008 | 0.036*** |

| (1.063) | (0.774) | (0.409) | (2.990) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.058*** |

| (0.275) | (0.175) | (0.240) | (2.726) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | −0.002 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.075*** |

| (0.056) | (0.010) | (0.111) | (2.747) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | 0.019 | −0.001 | 0.025 | 0.035 |

| (0.501) | (0.025) | (0.447) | (1.053) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | 0.049 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.051 |

| (1.143) | (0.187) | (0.161) | (1.349) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | 0.066 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.067 |

| (1.388) | (0.266) | (0.194) | (1.611) | |

Note: GRANK test statistics are given in parentheses. ***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.1 Test statistics for non-soft drink firms are available upon request.

D. Market reaction to the Implementation of SDIL on 6th April 2018

The SDIL came into effect on 6th April 2018. As it was announced by the UK government in advance, the implementation of SDIL on this day was not an unexpected shock to the market and therefore would not have caused changes in the stock market value of the soft drink firms. This absence of stock market response is confirmed in the Table D1 below which showed that the CARs to the SDIL implementation was not statistically significant for any firms regardless of the length of event window used.

Table D1.

CARs to the SDIL implementation on 6th April 2018.

| Event window | A. G. Barr Plc | Britvic Plc | Fever-Tree Drinks Plc | Nichols Plc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day (0,0) | 0.001 | 0.012 | −0.007 | −0.007 |

| (1.033) | (0.010) | (0.744) | (0.564) | |

| 3 days (-1,1) | 0.007 | 0.030 | 0.010 | −0.019 |

| (0.059) | (0.913) | (0.258) | (0.367) | |

| 5 days (-2,2) | 0.011 | 0.012 | −0.004 | −0.039 |

| (0.278) | (1.335) | (0.210) | (0.581) | |

| 7 days (-3,3) | 0.022 | 0.013 | −0.054 | −0.028 |

| (0.328) | (0.402) | (0.058) | (0.917) | |

| 9 days (-4,4) | 0.041 | 0.005 | −0.032 | −0.029 |

| (0.563) | (0.376) | (0.729) | (0.558) | |

| 11 days (-5,5) | 0.051 | 0.000 | −0.071 | −0.036 |

| (0.914) | (0.119) | (0.371) | (0.509) |

Note: Standard errors are given in parentheses. ***p< .01, **p< .05, *p< .1.

E. Robustness checks of the cross-sectional analysis

| SDIL announcement on 16th March 2016 |

Release of consultation report on 5th December 2016 |

Confirmation of SDIL rates on 8th March 2017 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day (0,0) |

3 days (-1,1) |

1 day (0,0) |

3 days (-1,1) |

1 day (0,0) |

3 days (-1,1) |

|

| Panel A: CARs estimated with FTSE All Share Index and a 120-day estimation window as dependent variable | ||||||

| Soft drinks | −0.042*** | −0.043 | −0.007* | −0.010 | 0.003 | 0.013 |

| (0.013) | (0.035) | (0.004) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.014) | |

| Firm size | −0.004*** | −0.001 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.004) | |

| Constant | 0.095*** | 0.038 | 0.003 | −0.038 | −0.019 | 0.020 |

| (0.032) | (0.034) | (0.016) | (0.073) | (0.018) | (0.092) | |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R-squared | 0.423 | 0.128 | 0.052 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.022 |

| Panel B: CARs estimated with FTSE 250 Index and a 250-day estimation window as dependent variable | ||||||

| Soft drinks | −0.043*** | −0.046 | −0.007* | −0.009 | 0.003 | 0.015 |

| (0.013) | (0.033) | (0.004) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.015) | |

| Firm size | −0.004*** | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.004) | |

| Constant | 0.091*** | 0.029 | 0.001 | −0.045 | −0.018 | 0.024 |

| (0.031) | (0.035) | (0.017) | (0.070) | (0.017) | (0.091) | |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R-squared | 0.428 | 0.146 | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 For both panels, the results on CARs over longer event windows were consistent with those reported in Table 6, which are available upon request.

References

- Beverage Daily . 2016. UK Sugar Tax on Sugar-sweetened Drinks: Industry Reaction. Available at: https://www.beveragedaily.com/Article/2016/03/17/UK-sugar-tax-on-sugar-sweetened-drinks-industry-reaction [Accessed October 20, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Beverage Daily . 2016. UK Sugar Tax on Sugar-sweetened Drinks: Industry Reaction. Available at: https://www.beveragedaily.com/Article/2016/03/17/UK-sugar-tax-on-sugar-sweetened-drinks-industry-reaction [Accessed August 9, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev T., Chou R.Y., Kroner K.F. ARCH modeling in finance. A review of the theory and empirical evidence. J. Econom. 1992;52(1–2):5–59. [Google Scholar]

- British Soft Drinks Association . 2015. UK Soft Drinks Responsibility Report 2015. Available at: www.britishsoftdrinks.com [Accessed October 21, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Britvic Plc . 2016. Preliminary Results – 30 November 2016. Available at: https://www.britvic.com/-/media/Files/B/Britvic-V3/documents/pdf/presentation/2016/preliminary-results-2016-report.PDF [Accessed November 18, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.J., Warner J.B. Using daily stock returns. The case of event studies. J. Financ. econ. 1985;14(1):3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Devos E., Hao W., Prevost A.K., Wongchoti U. Stock return synchronicity and the market response to analyst recommendation revisions. J. Bank. Financ. 2015;58:376–389. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor . Euromonitor International; 2019. Passport Global Market Information Database. [Google Scholar]

- Fever-Tree Drinks Plc . 2016. Preliminary Results Presentation 2015. Available at: https://fever-tree.com/en_GB/investors-results-and-reports [Accessed November 18, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Financial Times . 2017. Budget 2017: Revenues From UK’s Incoming Sugar Tax to Fall Short. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1e9703e0-0401-11e7-aa5b-6bb07f5c8e12 [Accessed October 20, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Financial Times . 2016. Nudge, Nudge! How the Sugar Tax Will Help British Diets. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/edf07088-ecfe-11e5-bb79-2303682345c8 [Accessed August 9, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune . 2016. Britain Just Imposed a Sugar Tax on Soft Drinks. Available at: https://irving.fortune.com/2016/03/16/sugar-tax-soft-drinks/ [Accessed August 9, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- FTSE Russell . 2019. FTSE UK Index Series. Available at: https://www.ftserussell.com/products/indices/uk [Accessed November 18, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G.V. Problems and solutions in conducting event studies. J. Risk Insur. 1990;57(2):282. [Google Scholar]

- Henson S., Mazzocchi M. Impact of bovine spongiform encephalopathy on agribusiness in the United Kingdom: results of an event study of equity prices. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002;84(2):370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Treasury H.M. 2016. Soft Drinks Industry Levy Summary of Response. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/575828/Soft_Drinks_Industry_Levy_-_summary_of_responses.pdf [Accessed October 12, 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons . 2017. Allocation of Funding From the Soft Drinks Industry Levy for Sport in Schools. Available at: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CDP-2017-0006#_ftn1 [Accessed December 3, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Investegate . 2016. Broker Forecast - Goldman Sachs Issues a Broker Note on Britvic PLC. Available at: https://www.investegate.co.uk/News/broker-forecast---goldman-sachs-issues-a-broker-note-on-britvic-plc/704241/ [Accessed November 18, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- ITV News . 2016. Sugar Tax on Soft Drinks: What You Need to Know. Available at: https://www.itv.com/news/2016-03-16/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-new-sugar-tax-on-soft-drinks/ [Accessed August 9, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.J., Kim J.-C. The effects of the BSE outbreak on the security values of US agribusiness and food processing firms. Appl. Econ. 2008;40(3):357–372. [Google Scholar]

- Kolari J.W., Pynnonen S. Nonparametric rank tests for event studies. J. Empir. Finance. 2011;18(5):953–971. [Google Scholar]

- Larcker D.F., Ormazabal G., Taylor D.J. The market reaction to corporate governance regulation. J. Financ. econ. 2011;101(2):431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Lopatta K., Kaspereit T. The cross-section of returns, benchmark model parameters, and idiosyncratic volatility of nuclear energy firms after Fukushima Daiichi. Energy Econ. 2014;41:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinlay A.C. Event studies in economics and finance. J. Econ. Lit. 1997;35:13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Malkiel B.G. The efficient market hypothesis and its critics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2003;17(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Masse I., Hanrahan R., Kushner J., Martinello F. The effect of additions to or deletions from the TSE 300 Index on Canadian share prices. Can. J. Econ. Can. D`economique. 2000;33(2):341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchi M., Ragona M., Fritz M. Stock market response to food safety regulations. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2009;36(4):571–595. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols Plc . 2017. Annual Report. Available at: https://www.nicholsplc.co.uk/Content/ReportPDFs/2017/2017AnnualReportFULL.pdf [Accessed November 18, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Ocado Group Plc . 2016. Q1 2016 Trading Statement. Available at: https://www.ocadogroup.com/-/media/Files/O/Ocado-Group/reports-and-presentations/2016/fy16-q1-15-03-2016.pdf [Accessed November 18, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Economics . 2016. The Economic Impact of the Soft Drinks Levy. [Google Scholar]

- Pacicco F., Vena L., Venegoni A. Event study estimations using stata: the estudy command. Stata J. 2018;18(2):461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Patell J.M. Corporate forecasts of earnings per share and stock price behavior: empirical test. J. Account. Res. 1976;14(2):246. [Google Scholar]

- Pendell D.L., Cho C. Stock market reactions to contagious animal disease outbreaks: an event study in Korean foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks. Agribusiness. 2013;29(4):455–468. [Google Scholar]

- Penney T., Adams J., White M. “LB4 industry reactions to the UK soft drinks industry levy: unpacking the evolving discourse from announcement to implementation.” in oral presentations. J. Epidmiol. Commun. Health. 2018:A43. 1-A43. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo V.F., Schroeder T.C. Evaluating the costs of meat and poultry recalls to food firms using stock returns. Food Policy. 2016;59:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters . 2016. Fever-Tree Aims to Mix It With Drinks Industry Elite. Available at: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-fevertree-interview-idUKKCN0Y30WR [Accessed October 21, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Salin V., Hooker N.H. Stock market reaction to food recalls. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001;23(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan V., Moorman C. Marketing alliances, firm networks, and firm value creation. J. Mark. 2009;73(5):52–69. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian . 2016. Irn-Bru Maker Plays Down Financial Impact of Sugar Tax. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/mar/29/irn-bru-ag-barr-soft-drinks-financial-impact-sugar-tax [Accessed August 9, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- The Independent . 2016. Sugar Tax: UK Businesses Claim Levy Will Result in Job Losses and Higher Prices. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/sugar-tax-uk-effects-obesity-levy-higher-prices-job-losses-businesses-claim-a7193351.html [Accessed December 3, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- The Independent . 2015. Sugar Tax Ruled Out by David Cameron: ‘There Are More Effective Ways of Tackling Obesity. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/david-cameron-rules-out-sugar-tax-there-are-more-effective-ways-of-tackling-obesity-a6704316.html [Accessed October 23, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- The Telegraph . 2016. Budget 2016: Sugar Tax on Soft Drinks. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/12195786/Budget-2016-Sugar-tax-on-soft-drinks.html [Accessed August 9, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang I.X. Economic consequences of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002. J. Account. Econ. 2007;44(1–2):74–115. [Google Scholar]