Abstract

Although prosocial abilities are associated with a wide range of healthy outcomes, few studies have experimentally examined socialization practices that may cause increased prosocial responding. The purpose of this study was to investigate conditions under which 2- and 3-year-old children can acquire prosocial behaviors through imitation. In Study 1 (N = 53), toddlers in the experimental condition watched a video of an adult comfort a woman in distress by performing a novel prosocial action without depicting how the woman was hurt. Parents then pretended they hurt their own finger and feigned distress. Children in the experimental condition were more likely to imitate the novel action relative to two control groups: (a) children who did not watch the video but witnessed a distressed parent, and (b) children who watched the video but witnessed parents engage in a neutral interaction. Thus, in a bystander context where children witnessed parent distress, toddlers imitated a general demonstration of how to respond prosocially to distress and applied this information to a specific distress scenario. In Study 2 (N = 54), the procedures were identical to those in the first study except that children were led to believe that they had transgressed to cause parent distress. In a transgressor context, children in the experimental condition were not more likely to imitate the prosocial behavior relative to children in either control group. These studies demonstrate that whether or not children have caused a victim’s distress greatly affects their ability to apply a socially learned prosocial behavior, possibly due to self-conscious emotions such as guilt and shame.

Keywords: Prosocial behaviour, Reparative behaviour, Imitation, Transgression, Self-conscious emotion, Guilt

Introduction

Toddlerhood is a crucial period for learning to recognize and respond prosocially to another person’s distress (Hay & Cook, 2007). Acquiring prosocial skills is important for young children because these behaviors are associated with competence in peer relationships and are protective against externalizing problems (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Hastings, Zahn-Waxler, Robinson, & Usher, 2000). Imitation is a well-established social learning mechanism through which toddlers learn new skills and connect socially with others (Over & Carpenter, 2012). Our previous work demonstrated that toddlers can learn a novel prosocial behavior and apply this behavior to help a distressed parent through imitation (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013). The purpose of the current studies was to replicate and extend this finding by testing whether toddlers can imitate a prosocial behavior to comfort a distressed parent when children were led to believe they had caused their parent’s distress.

The development of prosocial behaviors during toddlerhood

Prosocial behaviors are voluntary actions aimed at benefitting another person (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998). Research is increasingly recognizing the multidimensional nature of prosocial behaviors, which theorists argue can be classified into three subtypes: helping (i.e., helping another person achieve an instrumental goal such as obtaining an out-of-reach item), sharing (i.e., giving up a limited resource), and comforting (i.e., offering verbal or physical support in response to another person’s emotional distress; (Dunfield, 2014)). Empirical studies support the distinction of these subtypes as they have been found to emerge at different ages during development (Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010) and are fostered through different socialization practices (Pettygrove, Hammond, Karahuta, Waugh, & Brownell, 2013).

Whereas helping behaviors emerge as early as 12–14 months of age, comforting behaviors consistently appear latest—around 18 months (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2013; Svetlova et al., 2010). With older age across toddlerhood, children have been found to engage in more frequent comforting behaviors (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2013) and require less explicit distress cues in order to comfort victims (Svetlova et al., 2010). These changes are likely aided by parallel developments in children’s empathy (Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2009) and understanding of emotions and social rules (Hay & Cook, 2007). Moreover, studies have found that during toddlerhood the shared environmental effect on toddlers’ comforting behaviors was much larger than the genetic effect (Volbrecht, Lemery-Chalfant, Aksan, Zahn-Waxler, & Goldsmith, 2007). Thus, toddlerhood is a period of marked development of comforting behaviors during which environmental socialization practices may exert considerable influence.

Prosocial comforting behaviors can also be classified based on the context in which they occur. Studies have almost exclusively focused on prosocial behaviors that children use in response to distress they have witnessed as a bystander (hereafter referred to as prosocial behaviors). Reparative behaviors, on the other hand, are an understudied type of prosocial action that children use when they have caused distress as a transgressor that include attempts to make amends (e.g., fix a broken item), apologize, and confess to a transgression (Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007). Prosocial and reparative behaviors are related yet distinct. Both behaviors emerge during the second year of life (Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, Wagner, & Chapman, 1992), and children may use some of the same specific actions in both contexts (e.g., children may use comforting statements when they both witness and cause distress). However, whereas empathy often underlies prosocial behaviors, reparative behaviors are motivated by guilt in which children experience empathy and an awareness of fault for causing the victim’s distress (Tilghman-Osborne, Cole, & Felton, 2010). These behaviors also follow different developmental trajectories; for example, whereas prosocial behaviors have been found to decline around preadolescence (Nantel-Vivier, Pihl, Côté, & Tremblay, 2014), reparative behaviors have been found to remain stable from preschool through early adolescence (Donohue, Tillman, & Luby, 2019). Although studies have documented that young children help in a transgressor context, very little is known about how children come to learn these reparative skills.

The socialization of prosocial behavior in toddlers

A wealth of correlational studies have found associations between greater prosocial responding and socialization practices such as discipline, secure attachment, and emotion teaching in preschool and school-aged children (Hastings, 2007). Comparatively few studies have examined socialization practices associated with greater use of prosocial behaviors during toddlerhood, when these behaviors develop markedly. In one study, greater observed maternal scaffolding during a cleanup task was associated with 30-month-olds’ greater comforting behaviors toward an experimenter in distress during a separate paradigm (Pettygrove et al., 2013). Another correlational study found that parents’ observed elicitation of their 18- to 30-month-old children’s labeling and explanation of emotions while reading picture books was related to children’s greater comforting behaviors toward a distressed experimenter (Brownell, Svetlova, Anderson, Nichols, & Drummond, 2013), suggesting that children’s active involvement in emotion socialization facilitates their prosocial development.

Despite the fact that experimental designs can elucidate whether socialization practices cause greater prosocial responding, there have been few experimental studies of the socialization of prosocial behaviors in toddlers and no experimental investigations of specifically reparative behaviors. Direct instruction and praise (i.e., scaffolding) has been found to be effective when toddlers are in the process of mastering a specific prosocial task, but not once the task has been fully mastered (Warneken & Tomasello, 2013). For example, 13- to 15-month-olds who received direct instruction and praise used helping prosocial behaviors twice as often as infants in a control group who did not receive scaffolding (Dahl et al., 2017). In contrast, praise had no effect on helping in toddlers aged 20–24 months—a developmental age when most children readily use helping behaviors (Warneken & Tomasello, 2013); the researchers hypothesized that by 20 months of age toddlers have intrinsic motivations to use helping behaviors that are undermined by extrinsic rewards. Two, additional experimental studies established that another socialization practice, conversing about emotions, increases prosocial responding in 21- to 36-month-olds. Toddlers who listened to teachers read emotional stories and then engaged in teacher-led conversations about the emotional content displayed greater prosocial behaviors after 2 months compared with children who heard the stories but were not included in the conversations (Grazzani, Ornaghi, Agliati, & Brazzelli, 2016; Ornaghi, Brazzelli, Grazzani, Agliati, & Lucarelli, 2017).

Modeling may be an effective way to socialize prosocial behaviors in toddlers. Indeed, unlike scaffolding, modeling places few linguistic demands on toddlers, and it is also unlikely to undermine children’s intrinsic prosocial motivation because it does not involve instruction or commands. Moreover, modeling is a practice that can be initiated even if children have no spontaneous prosocial response to witnessing another person in distress. Furthermore, because research suggests that children might not act prosocially if they are unsure how to help (Staub, 1970), modeling may equip toddlers with specific prosocial strategies they can use, increasing their self-efficacy and, in turn, their prosocial responding. The current studies examined the causal role of modeling in children’s acquisition of prosocial and reparative behaviors through the mechanism of imitation.

Prosocial imitation during toddlerhood

Imitation refers to learning about a goal that can be met and attempting to meet this goal using the exact actions, or means, that a model demonstrated (e.g., (Want and Harris, 2002)). It is differentiated from mimicry, when a child reproduces a model’s specific means without an understanding of the goal of these actions. A wealth of literature has demonstrated that imitation is a powerful social learning mechanism through which children learn new skills and socially connect with a model. Most of this literature has examined how children acquire new behaviors through imitation. In two classic studies, 12-month-olds imitated a model by reproducing a goal, turning on a light, using the model’s specific means-touching the light with the head (Meltzoff, 1988); the children looked at the light after they touched it, suggesting that they understood the goal and, thus, were engaging in imitation rather than mimicry (Carpenter, Nagell, Tomasello, Butterworth, & Moore, 1998). Imitation also serves social functions of identification and affiliation (i.e., a child imitates a model to communicate that he or she and the model are alike and to be liked by the model; Over & Carpenter, 2012). Studies have demonstrated that 24-month-olds were more likely to imitate models who were socially responsive versus unresponsive (Nielsen, Simcock, & Jenkins, 2008) and who were socially engaged versus aloof (Nielsen, 2006).

Few studies have examined whether children can learn specific social behaviors, such as prosocial behaviors, through imitating a model’s example. Extant research has largely demonstrated that modeling encourages children’s prosocial responding through emulation, in which children learn the goal of a prosocial action and attempt to meet the goal using unique means. A series of studies of school-aged children demonstrated that children donated more winnings from a bowling game to charity if they had first witnessed a model donate winnings (e.g., Rushton, 1975); however, it is unclear whether modeling had its effect through imitation or emulation given that donating represented both the means and the goal. Similarly, a recent study by Schuhmacher et al. (2017) demonstrated that 16-month-old infants who viewed a model obtain out-of-reach items for an experimenter (i.e., instrumental helping) subsequently helped significantly more compared with infants in a no-model condition. That study demonstrated that modeling is a powerful means of learning to behave prosocially very early in development, although it is not clear through which social learning mechanism modeling had its effect given that children received credit if they helped in any way.

Only our previous study has directly investigated imitation as a mechanism through which toddlers learn prosocial comforting behaviors. In that study, 30-month-olds saw a video of an adult comfort a victim who had bumped her knee using a novel prosocial behavior—patting her head with a mitt (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013). Following the video, the toddler’s parent pretended to bump her knee, and children’s behaviors were coded from video. Toddlers who watched the video and witnessed their parent in distress were more likely to imitate by displaying the novel behavior relative to children who did not view the video but witnessed parent distress and children who watched the video but saw their parent engage in a neutral activity. Thus, this study demonstrated that toddlers can imitate a modeled prosocial behavior in a bystander context.

Social learning of reparative prosocial behaviors

Yet, no study to date has tested whether toddlers can apply socially learned prosocial behaviors in a context where children have transgressed to cause another person’s distress. Empirical evidence suggests that it may be more difficult for children to use prosocial behaviors in a transgressor context than in a bystander context. Most studies have demonstrated that, compared with when they are bystanders, toddlers and preschoolers are less prosocial as transgressors (Dunn & Brown, 1994; Dunn, Brown, Slomkowski, Tesla, & Youngblade, 1991), although some studies have found that they are more prosocial in the transgressor context (Vaish, 2018). Beyond mean-level differences in prosocial behavior, studies have also found that children are less empathic and more likely to display selfdistress, avoidance, and aggression as transgressors than as bystanders (Barrett, Zahn-Waxler, & Cole, 1993). As early as 18 months of age, toddlers display signs of discomfort after transgressing that are thought to represent a blend of guilt and shame such as avoidance, tension, arousal, distress, lessened positive affect, and increased negative affect (Kochanska, Gross, Lin, & Nichols, 2002). High levels of guilt and shame can elicit a considerable degree of affective discomfort and stress response in children (Lewis & Ramsay, 2002), which may help to explain why the transgressor context appears to be emotionally challenging. Yet, although reparative responding may be particularly difficult for toddlers, it is a critical skill to master given that reparative behaviors successfully alleviate children’s guilt (Donohue & Tully, 2019), and reparative deficits have been associated with externalizing disorders and depression in young children (Donohue et al., 2019).

Despite the importance of learning reparative skills, only two correlational studies have examined socialization practices associated with reparative behaviors. One study found that mothers’ use of inductive reasoning—wherein parents teach children about others’ needs and the effects of transgressions on victims—predicted 20- to 24-month-old toddlers’ observed reparative behaviors 5 months later (Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, & King, 1979). In the other study, parents’ use of authoritative parenting and low power-assertive discipline during toddlerhood predicted their children’s greater mention of reparative behaviors during a story completion task when the children were 8–10 years old (Kochanska, 1991). The current investigation is the first to date to use an experimental design to test a specific socialization practice, imitation, that may play a causal role in increasing reparative prosocial responding. Investigating potential mechanisms through which to promote reparative skills has crucial implications for preventing psychopathology.

Overview of the current study and hypotheses

Few experimental studies have tested causal mechanisms that underlie prosocial learning, and none has specifically examined reparative behaviors. Our previous study demonstrated that imitation is a mechanism though which toddlers can learn a prosocial comforting behavior and apply it in a bystander context (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013). The purpose of Study 1 was to test the replicability of this robust finding in a larger sample of toddlers. The hypothesis was that, in a bystander context, children who watch a video of an adult comfort another adult with a novel prosocial behavior will be more likely to imitate the prosocial behavior when their parent simulates distress relative to (a) a group of children who do not watch the video but witness their parent in distress and (b) a group of children who watch the video but witness their parent engage in a neutral interaction.

The purpose of Study 2 was to further extend this work by examining whether the causal effect of modeling on children’s increased prosocial behaviors extends to a transgressor context. The hypothesis was that in a context where children have transgressed to cause their parent’s distress, children who watch the prosocial demonstration video would be more likely to imitate the prosocial behavior to alleviate their parent’s distress relative to the other two groups of children. Thus, this study should answer whether modeling is an effective means through which children can learn and apply reparative behaviors through imitation.

Study 1

The design of Study 1 differed from that of our previously published study (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013) in two important ways. First, Study 1 used a video demonstration that depicted an adult in pain without showing how the pain was caused to examine whether toddlers need modeled demonstrations of how to help in response to very specific situations (e.g., how to help when someone bumps her knee) or whether, after viewing a very general demonstration of how to respond prosocially, children can generalize by imitating the prosocial behavior when they witness another person in distress regardless of the cause or context. Second, Study 1 added a task in which after the study paradigm ended children were asked how to use the mitt to examine whether any condition differences in children’s imitation during the paradigm reflect the fact that children did not learn the novel prosocial behavior at equivalent rates across conditions or, instead, reflect that children knew to use the novel prosocial behavior only in the appropriate context (i.e., when another person was in distress).

Method

Participants

Participants were a community sample (N = 54) of typically developing toddlers and their parent. One video file was lost, resulting in a final sample of N = 53. Participants were recruited from a pool of families interested in participating in research, by word of mouth, and by postings throughout the community. Children were either 2 years old (range = 26.60–34.30 months, M = 30.96 months, SD = 1.59) or 3 years old (range = 35.50–44.50 months, M = 37.84 months, SD = 2.48) and were typically recruited around 30 and 36 months of age. As such, analyses examined age as a categorical variable. The sample included 29 girls (53.7%) and 48 mothers (88.9%). Parents identified children’s race as 70.4% White, 24.1% Black, 3.7% biracial (White and Black), and 1.9% Asian. Parents identified children’s ethnicity as 77.78% not Latinx/Hispanic and 14.81% Latinx/Hispanic, with 7.41% not reporting.

Experimental design

The design was based on that of Williamson, Donohue & Tully, (2013). Depending on the experimental condition, children experienced either parental distress (pain) that the child witnessed as a bystander or a neutral interaction in which the parent feigned interest in a toy.

Materials

Novel prosocial item.

A green cleaning mitt (24 ×18.5 cm) with multiple 1-inch cloth tentacles covering one side (Fig. 1A) was used to demonstrate a novel prosocial behavior in a video vignette. This unusual object was an item that children (a) would be unlikely to recognize and (b) would not have previously used in a prosocial context.

Fig. 1.

Still photos of the mitt stimulus (A) and pounding toy (B).

Distress item.

A pounding toy composed of a bench of blocks and a hammer (Fig. 1B) was used to create a situation in which parents feigned distress.

Video vignette.

One 45s video vignette (presented on a 9-inch screen) was used to demonstrate the novel prosocial behavior. A video demonstration, rather than a live presentation, ensured competent acting and uniformity of presentation. Research has demonstrated that infants and toddlers can imitate a model’s demonstration presented through video (Hayne, Herbert, & Simcock, 2003). The video begins as Actor 1 bends in pain, demonstrates a distressed facial expression and vocal tone, and says “Ow! My hand. It really hurts. Ow.” Actor 1 rubs her hand, says “Ow,” and demonstrates a pained facial expression. Actor 2 then models the target acts (prosocial behavior); he says “I’ll help you,” puts the mitt on his hand, and pats Actor 1’s head with the mitt four times, first with palm down and then with palm up in an alternating fashion (Fig. 2). Actor 1 then recovers by smiling and saying “I feel better now.” Thus, the video does not depict the cause of the victim’s pain.

Fig. 2.

Still photo of the video vignette.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from parents. The experimenter (“E”) trained the parent on acting out parent distress or the neutral interaction in a testing room while a research assistant (RA) engaged in a warm-up period with the child in a separate room. The remainder of the session was videotaped.

The child either watched or did not watch the video vignette. Then, E placed the mitt on the table in front of the child for 10 s, giving the child the opportunity to examine the object. Next, leaving the mitt with the child, E handed the parent and child the pounding toy to play with and left the room. The parent then feigned parental distress or the neutral interaction. E reentered the room, which ended the paradigm and cued the parent to recover (if the parent had feigned distress). After the paradigm, the parent was asked one follow-up question and the child completed a follow-up learning task (described below).

Experimental conditions.

Children were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions. For readability, procedures are described in full as children in each condition experienced them.

In the experimental condition, the child watched the video vignette demonstrating the novel prosocial behavior. The parent followed the bystander distress script; the parent pretended to hammer her or his own finger while playing with the pounding toy. The parent followed a short script immediately after hurting the finger: “Ow! I hit my finger. It really hurts.” The parent used a stopwatch and repeated this line after 30 s. Throughout the entire incident (60 s), the parent pretended to be in pain by rubbing the finger and using pained facial expressions and tone of voice. This condition assessed the child’s imitation of the novel prosocial behavior.

To obtain parents’ ratings of children’s perceived fault, the parent completed one written follow-up question that asked “Do you think your child thought what happened with the pounding toy was his/her fault?” The parent responded using a 4-point scale (0 = definitely not, 1 = probably not, 2 = probably yes, 3 = definitely yes).

In the learning task, E placed the mitt in front of the child and said “Show us how to use this,” to assess whether children learned the novel prosocial behavior from the video. The child’s actions with the mitt were scored from videotape.

In the no-video control condition, the child did not watch the video and the parent then followed the bystander distress script. This condition assessed the child’s spontaneous use of the mitt when confronted with a distressed parent.

In the no-distress control condition, the child watched the video and the parent then followed the neutral script; the child hammered with the pounding toy while the parent feigned interest in the toy. The parent bent to inspect the toy and used a neutral tone while following a short script: “Oh. Look at this block. Oh look.” The parent used a stopwatch and repeated this line after 30 s. Throughout the entire incident (60 s), the parent continued to express interest in the toy using a neutral tone and facial expressions. The neutral script matched the bystander distress script in terms of approximate duration, body positions, and number and length of vocalizations. This condition assessed whether or not replicating the target acts occurred for a prosocial purpose—in other words, whether the child’s use of the novel prosocial behavior reflected imitation or mimicry.

Scoring and rating of observational data.

RAs who were blind to the study hypothesis and whether or not children watched the video scored or rated children’s behaviors on three measures during the test phase, which is the 60 s period starting when the parent began to initiate the script and ending when the experimenter reentered the room. One measure of children’s behaviors following the test phase was also scored. Interrater reliability (IRR) was assessed with two-way, mixed, absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs).

Conventional acts.

Children’s attempts to relieve parent distress using previously learned, nondemonstrated prosocial behaviors during the test phase were rated. For example, these behaviors included, but were not limited to, hugging the parent, kissing the parent’s finger, making prosocial statements (e.g., reassuring the parent that he or she was going to be okay), and attempting help (e.g., looking for a bandage). The presence and intensity of these behaviors were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = none, 4 = strong) based on the systems used by Williamson, Donohue & Tully, (2013) and Zahn-Waxler, Cole, Welsh, and Fox (1995); the ICC was .90.

Distress.

The presence and intensity of children’s distress (facial, vocal, or gestural/postural expressions of generalized distress, including concern, anxiety, sadness, or anger) were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = none, 4 = strong) based on the system used by Zahn-Waxler et al. (1995); the ICC was .94.

Target acts (imitation).

Children’s production of the demonstrated novel prosocial action with the mitt during the test phase was scored as the measure of imitation. Children received 1 point each for replicating three possible demonstrated actions with the prosocial item (wearing the mitt, patting the parent, and rotating the mitt from palm up to palm down) following the exact coding scheme published in Williamson, Donohue & Tully, (2013). Scoring was designed to give children credit for partial fulfillment of the target acts; the ICC was 1.00.

Learning.

Children’s production of the demonstrated novel prosocial action following the test phase (i.e., when children were directly asked how to use the mitt) was also scored using the identical scheme that was used to score target acts; the ICC was 1.00.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Correlations among variables.

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for study variables are presented in Table 1. Correlations among study variables are displayed in Table 2. There were no significant correlations.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables.

| Possible range | Observed range | Mean (SD) or frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample (N = 53) | Experimental (n = 19) | No-video control (n = 17) | No-distress control (n = 17) | |||

| 1. Age (% 2 years old) | 57.4% | 65.0% | 41.2% | 64.7% | ||

| 2. Gender (% female) | 53.7% | 50.0% | 52.9% | 58.8% | ||

| 3. Race | ||||||

| White | 70.4% | 75.0% | 70.6% | 64.7% | ||

| Black | 24.1% | 15.0% | 23.5% | 35.3% | ||

| Biracial | 3.7% | 10.0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Asian | 1.9% | 0% | 5.9% | 0% | ||

| 4. Ethnicity (% Hispanic/Latinx) | 14.81% | 20.0% | 11.8% | 11.8% | ||

| 5. Parent gender (% mothers) | 88.9% | 85.0% | 82.4% | 100.0% | ||

| 6. Conventional acts | 0–4 | 0–4 | 1.15 (1.08) | 1.42 (1.07) | 1.82 (0.88) | 0.18 (0.39) |

| 7. Distress | 0–4 | 0–4 | 1.00 (0.92) | 1.32 (0.95) | 1.47 (0.72) | 0.18 (0.39) |

| 8. Target acts | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0.42 (0.77) | 1.00 (0.94) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.12 (0.49) |

| 9. Parent fault question | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0.49 (0.87) | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.47 (0.87) | 1.00 (1.01) |

| 10. Learning | 0–3 | 0–3 | 1.28 (0.85) | 1.46 (0.88) | - | 1.60 (0.83) |

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables in overall sample.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.0 | ||||||

| 2. Sex | −.18 | 1.0 | |||||

| 3. Parent gender | .05 | .03 | 1.0 | ||||

| 4. Conventional acts | −.34 | −.07 | .02 | 1.0 | |||

| 5. Distress | −.02 | .24 | .07 | −.21 | 1.0 | ||

| 6. Target acts | −.19 | .30 | .16 | −.12 | −.12 | 1.0 | |

| 7. Learning | .18 | −.35 | −.01 | −.17 | −.38 | .13 | 1.0 |

Note. 1 = boys; 0 = girls and 1 = fathers; 0 = mothers.

Group differences among variables.

Independent-samples t tests did not reveal significant differences in mean levels of target acts scores by child or parent demographic characteristics within the full sample or any of the three conditions. Chi-square tests using the Yates correction revealed that neither the number of paternal parent actors nor the number of children in each age group (2-year-olds vs. 3year-olds) was significantly different across conditions. Thus, covariates were not included in the tests of the study hypothesis.

Manipulation checks

Four manipulation checks were conducted. Two checks examined the effect of condition on children’s conventional acts and distress to determine whether the bystander distress script successfully elicited children’s prosocial behaviors and distress. One check examined the effect of condition on parent ratings of children’s perceived fault to determine whether children understood that they were not at fault for causing the parent’s distress. A final check examined the effect of condition on children’s learning scores to determine whether children who watched the video learned the novel prosocial action at equivalent rates regardless of condition. Because assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA) were violated (i.e., normality and homogeneity of variance), the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for each analysis.

Children’s conventional acts.

Children’s conventional acts ratings were significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 25.28, p ≤.001. Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction confirmed statistically significant differences in conventional acts ratings between the no-distress control (mean rank = 12.59) and experimental condition (mean rank = 30.92, p = .001) conditions and the no-distress control and no-video control (mean rank = 37.03, p ≤.001) conditions, but not between the experimental and no-video control conditions. Thus, children in a condition that used the bystander distress script used more nondemonstrated prosocial behaviors than children in the condition where parent distress did not occur.

Children’s distress.

Children’s rated distress was also significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 25.68, p ≤.001. Pairwise comparisons yielded statistically significant differences in distress scores between the no-distress control (mean rank = 12.53) and experimental (mean rank = 31.95, p ≤.001) conditions and the no-distress control and no-video control (mean rank = 31.95, p ≤.001) conditions, but not between the experimental and no-video control conditions. Thus, children in a condition that used the bystander script were rated to be significantly more distressed than children in the condition where parent distress did not occur.

Parents’ ratings of children’s perceived fault.

One parent was not asked this question due to experimenter error. Of 35 parents of children in a condition involving the bystander distress script, 29 parents (82.9%) responded “definitely not,” 2 (5.7%) responded “probably not,” and 4 (11.4%) responded “probably yes” (no parent responded “definitely yes”). Thus, the majority of parents (88.6%) responded that their children did not feel at fault for causing parent distress.

Children’s learning.

Finally, we compared learning scores between children in the two conditions that watched the novel prosocial demonstration video. There was no significant difference in children’s learning scores between children in the experimental and no-distress control conditions, χ2(1) = 0.30, p = .586.

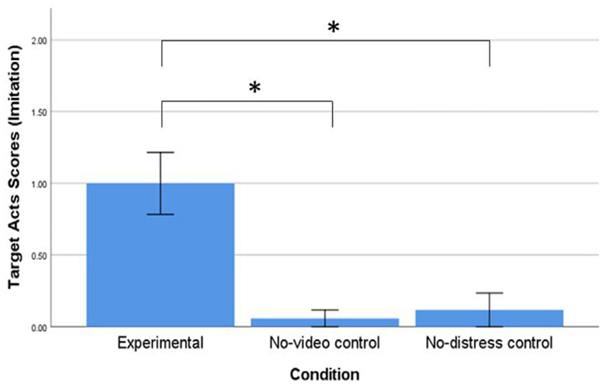

Hypothesis test

Regarding the effect of condition on target acts scores, condition differences in target acts scores were examined to investigate children’s imitation of the demonstrated novel prosocial behavior. Because assumptions of ANOVA (i.e., normality and homogeneity of variance) were violated, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used. Children’s target acts scores were significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 17.71, p ≤.001 (Fig. 3). Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction showed that children in the experimental condition (mean rank = 35.97) had significantly higher target acts scores than children in the no-video control condition (mean rank = 21.79, p = .001) or the no-distress control condition (mean rank = 22.18, p = .001). There was not a significant difference between the two control conditions.

Fig. 3.

Bar graph of effect of condition on target acts scores *p < .01.

Indeed, 11 children in the experimental condition (57.89%) produced at least one target act (wearing the mitt, patting the parent, or rotating the mitt), and 8 of these children (42.11%) received a score of 2 or more during the test period, indicating that they acted on their parent using the mitt. In contrast, only 1 child out of both control groups combined (n = 34) scored above a 0 (2.9%). Fisher’s exact tests indicate a difference in the number of children who scored 2 or more versus less than 2 between the experimental group and each control group (p ≤.001). The size of the effect of condition on target acts scores was large in magnitude (d = 1.42). It is important to note descriptively that 6 of the 8 children who acted on their parent with the mitt made statements that provided strong evidence that their imitation was prosocially motivated. Indeed, 3 of these children made statements immediately before imitating—for example, “I’ll fix it” and “I can do it, I got this on [pointing to mitt].” An additional 3 children confidently made statements after imitating such as, “It’s better, that’s better” and “You feel better.”

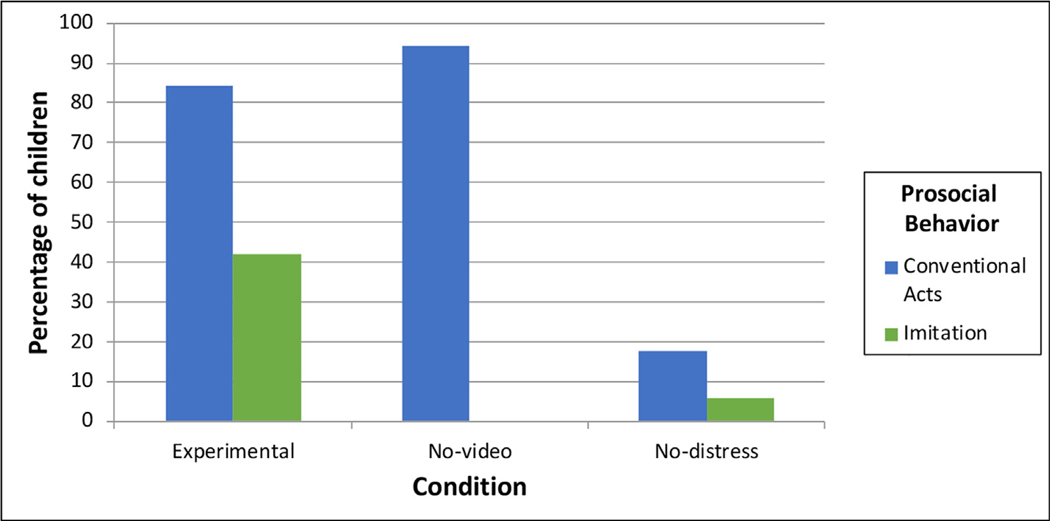

Associations between conventional acts and target acts

Following children’s impressive engagement in both imitation and conventional prosocial behaviors, we explored the frequency of both types of prosocial behavior and whether they were related. Fig. 4 shows that of children in a condition that used the bystander distress script (n = 36), 8 imitated (i.e., by receiving a target acts score of 2 or more) and 32 (88.89%) used conventional acts (i.e., by receiving a score of 1 more). In total, 33 children (91.67%) used either imitation or conventional acts to comfort, meaning that only 3 children did not use any prosocial behaviors. Target acts scores and conventional acts scores of children in the experimental condition were positively but nonsignificantly correlated (r = .28, p = .25).

Fig. 4.

Bar graph of frequencies of imitative and conventional prosocial behavior by condition. Note that children were considered to have imitated if they earned a target acts score of 2 or more and were considered to have used conventional prosocial behaviors if they earned a conventional acts score of 1 or more.

Discussion

The purpose of Study 1 was to examine whether a previously published effect of modeling on toddlers’ prosocial imitation was robust and generalizable (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013). Manipulation tests established that the study mishap was believable given that it elicited children’s own distress and previously learned prosocial behaviors such as kissing their parent’s finger. This was important to establish; if the mishap did not elicit prosocial behaviors that were already in children’s repertoires, it is unlikely that it would have stimulated children’s use of a novel prosocial action. A majority of parents reported that their children understood that they did not cause the parent’s distress, indicating that the bystander context was clear.

Consistent with the original study on this topic, we found a large causal effect of modeling on toddlers’ prosocial behaviors through the mechanism of imitation. Because it is possible that children in the original study were cued to use the mitt when they saw their parent bump her or his knee after seeing a model bump her knee in the video, we improved on this study by removing the cause of the distress in the video. Toddlers who watched a video of an adult help a woman in distress using a novel prosocial behavior imitated the novel behavior to help their distressed parent (experimental condition). Children who did not watch the video (no-video control condition) did not produce the novel behavior, suggesting that children did not spontaneously produce the novel action. Moreover, children who watched the video but then witnessed their parent engage in a neutral activity (no-distress control condition) also did not produce the complete novel behavior, indicating that children used the novel behavior only to ease another person’s distress and were not simply “trying out” a newly demonstrated action. In other words, toddlers’ production of the novel prosocial behavior was purposeful and, thus, reflected imitation and not mimicry. Children’s verbalizations while imitating (e.g., “I will fix it”) added particularly compelling evidence that their imitation was prosocially motivated. Results from a learning task further established that although children in the two conditions that watched the video learned how to use the mitt at equivalent rates, children used this novel behavior only in a situation that called for prosocial action—when they witnessed their parent in distress. Future studies could further demonstrate that children were not cued or simply “trying out” the novel action by including a condition in which the video depicts that the action with the mitt is not effective in relieving distress. Greater imitation in a condition in which children watch the video where the mitt is effective would support that children’s use of the mitt is purposeful and prosocial.

Interestingly, the relationship between children’s previously learned prosocial behavior scores and their prosocial imitation scores was positively but nonsignificantly correlated. This could reflect either that the two forms of prosocial comforting were related yet distinct or that there was an effect that we could not detect due to low power. Teasing apart the relationship between prosocial imitation and conventional helping would be an interesting topic of future research; for example, if there is a relationship, it would be important to examine the possibility that engaging in prosocial imitation promotes other prosocial behavior. Moreover, the 2- and 3-year-olds in our study learned and applied a new prosocial behavior through imitation despite already possessing a rich repertoire of comforting prosocial behaviors. As studies increasingly demonstrate the emergence of prosocial behavior even before the first birthday (e.g., Davidov, Zahn-Waxler, Roth-Hanania, & Knafo, 2013), future research should examine prosocial imitation during infancy, which may have implications for bolstering children’s prosociality during a particularly sensitive period of prosocial development. On the other hand, modeling could be a means through which children’s existing prosocial skills are refined or through which even older children can learn particularly complex prosocial behaviors such as apologies (Ely & Gleason, 2006).

In sum, findings from Study 1 demonstrate that modeling is an important domain for learning prosocial behaviors, which adds to an experimental literature that has largely investigated direct instruction and scaffolding (e.g., Warneken & Tomasello, 2013). Moreover, we found that toddlers can watch a general demonstration that does not depict the cause of a victim’s distress and apply this behavior to help a hurt parent in a specific distress scenario (i.e., when the parent has hit her or his finger). Our findings suggest that modeled demonstrations may also be an effective way to socialize toddlers’ prosocial skills and that toddlers would likely be able to generalize from demonstrations to a variety of specific distress scenarios.

Study 2

A second study was conducted to examine whether children’s social learning of prosocial behaviors extends to a transgressor context in which children are led to believe they have caused their parent’s distress. As there was a large causal effect of modeling on children’s learning of a prosocial behavior, modeling may have a similarly large effect on children’s reparative behaviors. On the other hand, as studies suggest that using reparative behaviors might be more difficult for toddlers, the size of the effect may be smaller.

Method

Participants

Participants were a community sample (N = 54) of typically developing toddlers and their parent recruited through the identical means as in Study 1. Children were either 2 years old (range = 29. 3–33.7 months, M = 31.52 months, SD = 1.05) or 3 years old (range = 35.1–47.6 months, M = 37.85 months, SD = 3.22) and were again recruited around 30 and 36 months of age. The sample included 29 girls (53.7%) and 44 mothers (81.5%). Parents reported children’s race as 76% White, 15% Black, and 9% biracial (White and Asian). Parents identified children’s ethnicity as 98.1% not Latinx/Hispanic and 1.9% Latinx/Hispanic.

Experimental design

The experimental design was identical to that of Study 1 in all ways (materials, procedure, experimental conditions, measures, and coding) except that the distress script varied such that children were led to believe that they had caused their parent’s distress as a transgressor. The design of the transgression mishap was adapted from previous research (Barrett et al., 1993; Kochanska et al., 2002).

Materials

The mitt, pounding toy, and video vignette from Study 1 were used.

Procedures

Procedures were identical to those of Study 1 except that the distress script in this study was a transgressor distress script; the parent slipped a finger on top of a block as the child hammered, pretending that the child hammered the parent’s finger. The parent followed a short script immediately after hurting the finger: “Ow! You hit my finger. It really hurts.” The parent used a stopwatch and repeated the line after 30 s. Throughout the entire incident (60 s), the parent pretended to be in pain. Children assigned to a condition involving the transgressor distress script were debriefed at the very end of the study. As in other studies that use a pretend transgression, E explained to the child that hurting the parent was not the child’s fault. The neutral script was identical to that of Study 1.

Regarding the scoring and rating of observational data, RAs scored or rated the same measures as in Study 1. The ICC was .93 for conventional acts, .85 for distress, .98 for target acts (imitation), and 1.00 for learning.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Correlations among variables.

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for study variables are presented in Table 3. Correlations among study variables are displayed in Table 4. Older children displayed more target acts and conventional acts; thus, age was included as a covariate in the test of the study hypothesis. Children who produced target acts (imitated the novel prosocial behavior) also tended to display conventional acts (previously learned prosocial behaviors). Children’s greater distress was associated with their greater use of previously learned prosocial behaviors.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of primary study variables.

| Possible range | Observed range | Mean (SD) or frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample (N = 54) | Experimental (n = 18) | No-video control (n = 18) | No-distress control (n = 18) | |||

| 1. Age (% 2 years old) | 55.6% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 66.7% | ||

| 2. Gender (% female) | 53.7% | 55.6% | 55.6% | 50.0% | ||

| 3. Race | ||||||

| White | 75.9% | 83.3% | 77.8% | 66.7% | ||

| Black | 14.8% | 11.1% | 16.7% | 16.7% | ||

| Biracial | 9.3% | 5.6% | 5.6% | 16.7% | ||

| 4. Ethnicity (% Hispanic/Latinx) | 1.9% | 0% | 5.6% | 0% | ||

| 5. Parent gender (% mothers) | 81.5% | 88.9% | 72.2% | 83.3% | ||

| 6. Conventional acts | 0–4 | 0–4 | 1.31 (1.29) | 2.00 (1.24) | 1.83 (1.10) | 0.11 (0.32) |

| 7. Distress | 0–4 | 0–4 | 1.17 (0.97) | 1.89 (0.96) | 1.22 (0.73) | 0.39 (0.50) |

| 8. Target acts | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0.13 (0.48) | 0.28 (0.67) | 0.11 (0.47) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 9. Parent fault question | 0–3 | 0–3 | 1.98 (1.10) | 2.33 (0.59) | 2.44 (0.92) | 1.12 (1.22) |

| 10. Learning | 0–3 | 0–3 | 1.06 (0.72) | 0.93 (0.70) | - | 1.18 (0.73) |

Table 4.

Correlations among study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | |||||

| 2. Sex | .37** | ||||

| 3. Conventional acts | .34* | −.05 | |||

| 4. Distress | .04 | −.05 | .49** | ||

| 5. Target acts | .31* | .14 | .33* | .08 | |

| 6. Learning | −.07 | −.27 | −.04 | −.17 | −. 06 |

Note. 1 = boys; 0 = girls.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Group differences among variables.

Boys (M = 35.86, SD = 4.59) were older than girls (M = 33.17, SD = 2.77), t(51) = 2.631, p = .01. Independent-samples t tests revealed no significant differences in target acts scores by child or parent demographic characteristics within the overall sample or within any of the three conditions. Chi-square tests using the Yates correction revealed that neither the number of paternal parent actors nor the number of children in each age group was significantly different across conditions. Thus, no covariates other than age were included in the test of the hypothesis.

Manipulation checks

Four manipulation checks were again conducted. Two checks examined the effect of condition on children’s conventional acts and distress to determine whether the transgressor distress script successfully elicited children’s prosocial behaviors and distress. One check examined the effect of condition on parents’ ratings of children’s perceived fault to determine whether children understood that they were at fault for causing their parent’s distress. A final check examined the effect of condition on children’s learning scores to determine whether children who watched the video learned the novel prosocial action at equivalent rates regardless of condition. Because assumptions of ANOVA were violated (i.e., normality and homogeneity of variance), the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for each analysis.

Children’s conventional acts.

Children’s conventional acts ratings were significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 28.84, p ≤.001. Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction confirmed statistically significant differences in conventional acts ratings between the no-distress control (mean rank = 11.83) and experimental (mean rank = 35.94, p ≤.001) conditions and the no-distress control and no-video control (mean rank = 34.72, p ≤.001) conditions, but not between the experimental and no-video control conditions. Thus, children in a condition involving the transgressor distress script used more nondemonstrated prosocial behaviors than children in the condition where a transgression did not occur.

Children’s distress.

Children’s rated distress was also significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 24.98, p ≤.001. Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction showed statistically significant differences in distress scores between the no-distress control (mean rank = 14.39) and experimental (mean rank = 38.69, p ≤.001) conditions and the no-distress control and no-video control (mean rank = 29.42, p = .002) conditions, but not between the experimental and no-video control conditions. Thus, children in a condition that involved the transgressor distress script were rated to display significantly more distress than children in the no-distress control condition where a transgression did not occur.

Parents’ ratings of children’s perceived fault.

Of the 36 parents of children in a condition involving the bystander distress script, 19 parents (52.8%) responded “definitely yes,” 13 (36.1%) responded “probably yes,” 3 (8.3%) responded “probably no,” and 1 (2.8%) responded “definitely no” to the question asking whether they thought their children felt at fault for causing the parent’s distress. Thus, the majority of parents (88.9%) indicated that their children probably or definitely understood that they were at fault for the parent’s distress.

Children’s learning.

Finally, we compared learning scores between children in the two conditions that watched the novel prosocial demonstration video. There was no significant difference in children’s learning of the novel prosocial action from the video between children in the experimental and no-distress control conditions, χ2(1) = 2.02, p = .57.

Hypothesis test

Regarding the effect of condition on target acts scores, condition differences in target acts scores were examined to investigate children’s imitation of the demonstrated novel prosocial behavior. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to allow for controlling the effect of children’s age on target acts scores. There was no effect of condition on target acts scores when controlling for age, F(5, 48) = 1.64, p = .20 (Fig. 5A). Nonparametric tests using the Kruskal–Wallis H test support this result. Children’s target acts scores were not significantly different among conditions, χ2(2) = 3.65, p = .16. Indeed, only 2 children (11.11%) in the experimental group received a score above a 1, reproducing at least two target acts (wearing the mitt, patting the parent, and/or rotating the mitt).

Fig. 5.

Bar graphs depicting no effect of condition on target acts scores in a transgressor context (A) and frequencies of imitative and conventional prosocial behavior (B) by condition. Note that children were considered to have imitated if they earned a target acts score of 2 or more and were considered to have used conventional prosocial behaviors if they earned a conventional acts score of 1 or more.

Associations between conventional acts and target acts

As in Study 1, we conducted additional analyses to explore both types of prosocial behavior (Fig. 5B). Of children in a condition that used the bystander distress script (n = 36), 2 imitated (i.e., by receiving a target acts score of 2 or more) and 33 (91.67%) used conventional acts (i.e., by receiving a score of 1 or more). In total, 33 children (91.67%) used either imitation or conventional acts to comfort, meaning that only 3 children did not use any prosocial behaviors. Because only 2 children in the experimental condition imitated, it was not possible to meaningfully examine how children’s imitation related to their use of conventional prosocial behaviors.

Comparing prosocial behavior across studies

The interaction between study and condition on target acts scores was examined to investigate differences in prosocial imitation across studies. Independent-samples t tests and chi-square tests using the Yates correction revealed no significant differences in child or parent demographic characteristics between studies, suggesting that the two studies are samples from the same population. A factorial ANCOVA was conducted with study and condition as two between-subjects factors predicting target acts scores while controlling for age. There was a significant interaction between study and condition on target acts scores, F(1, 99) = 5.38, p ≤.001, partial η2 = .10. Specifically, there was a significant difference between studies in mean target acts scores in the experimental condition, F(1, 99) = 16.911, p ≤.001, partial η2 = .15, but not in the no-video control condition, F(1, 99) = 0.120, p = .73, partial η2 = .001, or the no-distress control condition, F(1, 99) = 0.39, p = .54, partial η2 = .004. In the experimental condition, bystanders (M = 1.02, SE = 0.13) received significantly greater target acts (imitation) scores than transgressors (M = 0.25, SE = 0.13).

Discussion

The aim of Study 2 was to test whether toddlers’ social learning of prosocial behaviors extends to contexts in which children have transgressed to cause another person’s distress. Manipulation tests established that the study paradigm created a believable transgression that elicited children’s distress and previously learned prosocial behaviors such as apologizing. Parents largely reported that their children understood that they caused the mishap, which was critical because whether or not children were at fault for their parent’s distress was the only variable that differed between Study 1 and Study 2. Children who watched the prosocial demonstration video and were led to believe that they transgressed (experimental condition) were not more likely than children in either control condition to imitate the novel prosocial behavior to help their distressed parent. Thus, there was no effect of modeling on toddlers’ prosocial behaviors in a transgressor context. Analyses comparing studies confirmed that children in the experimental condition engaged in significantly greater prosocial imitation when they were bystanders (Study 1) than when they were transgressors (Study 2). Interpretations of this result are discussed below.

General discussion

The purpose of the current studies was to investigate contexts in which toddlers can learn and apply prosocial behaviors through imitation. Study 1 demonstrated that toddlers who watched a video of a model help an adult in distress with a novel prosocial behavior imitated and applied the novel prosocial behavior when they witnessed a parent in distress. In stark contrast, Study 2 found no evidence supporting children’s ability to imitate the novel prosocial behavior in a transgressor context despite the fact that the only variable that differed between the two studies was whether or not children were at fault for causing their parent’s distress.

Although we anticipated that toddlers’ imitation of a prosocial behavior might be more difficult in a transgressor context, the extremely low rates of transgressor children’s imitation were quite surprising given the very large effect size (d = 1.42) of prosocial imitation in a bystander context (Study 1). Yet, although transgressor children did not imitate the novel prosocial action, they did engage in an impressive amount of nondemonstrated, previously learned prosocial behaviors such as apologizing and hugging their parent. In other words, it is not that children were not prosocial in the transgressor context; they simply used previously learned prosocial behaviors rather than imitating the novel prosocial action. In contrast, children in the bystander context used a combination of both previously learned prosocial behaviors and the newly learned prosocial behavior.

In both studies, the pretend mishap induced children’s distress. Because toddlers experience guilt and shame as transgressors (Kochanska et al., 2002), the distress that children experienced in the transgressor study likely included these self-conscious emotions. Self-conscious emotions may have motivated toddlers’ use of previously learned prosocial behaviors while simultaneously interfering with their use of the newly learned prosocial behavior. Guilt, which has been found to motivate reparative prosocial behaviors (Donohue & Tully, 2019), may have motivated children to act prosocially using previously learned prosocial behaviors. At the same time, it is possible that self-conscious emotions overwhelmed children such that they were unable to imitate a newly learned prosocial act. As discussed previously, high levels of guilt and shame can elicit a considerable degree of affective discomfort and stress response in children (Lewis & Ramsay, 2002). Reproducing novel acts through imitation is more cognitively taxing than using previously learned behaviors (Masur & Ritz, 1984) and, thus, may be more vulnerable to the interference of such strong emotions. Although the focus of this investigation was behavioral and did not aim to study children’s affective responses to the transgressions, future studies should examine the potential role of guilt and shame in (a) impairing children’s prosocial imitation and/or (b) motivating children’s use of previously learned prosocial behaviors in a transgressor context.

The differing degree of responsibility for successfully alleviating a victim’s distress between the two studies/contexts may have influenced the prosocial strategies that children chose. Whereas in a bystander context a child might choose to help, in a transgressor context a child has caused harm and, thus, is personally responsible for successfully mending the transgression (Tilghman-Osborne et al., 2010). Guilt feelings, of which an awareness of personal responsibility for a transgression is a key component, might further amplify this sense of personal responsibility, perhaps encouraging children’s use of their own strategies to help the parent rather than the one provided for them in the demonstration. Moreover, the transgressor context might be a particularly “high-stakes” situation made so by children’s greater sense of responsibility to use prosocial action as well as children’s desire to alleviate their own guilt. The most fitting explanation for the data, then, may be that in the highstakes transgressor context children fell back on previously learned, previously successful behaviors rather than attempting a riskier newly learned behavior. In contrast, the bystander children may have been willing to try the untested, and thus risky, prosocial strategy because as bystanders they were not personally responsible for resolving the parent’s distress. Children’s willingness to act prosocially depends on their degree of self-efficacy or belief in their ability to help (Bandura, 1977). Children may be more confident in their ability to competently use previously effective strategies rather than new prosocial strategies in contexts where successfully relieving distress feels particularly imperative. An alternative explanation for our findings might be that children fell back on previously learned prosocial behaviors not because they caused the distress but rather because they knew that the parent did not cause her or his own distress. Future studies that examine conditions in which a third party harms the parent would help to shed light on the current findings.

Of course, it is possible that modeling is simply not an effective means for promoting children’s prosocial behaviors in a transgressor context; instead, other socialization practices may be more effective. Mother’s use of inductive reasoning has been associated with children’s increased reparative prosocial responding (Zahn-Waxler et al., 1979); future studies that pinpoint components of effective inductions might inform interventions aimed at increasing children’s reparative skills. Mechanisms that do not necessarily involve socialization may also be implicated; for example, fostering children’s better emotion regulation during distressing transgressions may facilitate their reparative responding. Yet, it is also possible that modeling can promote reparative behaviors but that toddlers need to view a prosocial demonstration multiple times before they will take the risk of applying the novel prosocial behavior in a transgressor context. Indeed, multiple demonstrations might increase children’s confidence in the effectiveness of the novel behavior and in turn increase their use of the behavior when confronted with a distressed victim. Future research that tests these opposing explanations for the current findings would further inform the effectiveness of modeling in promoting toddlers’ reparative behaviors.

Finally, the stark contrast of children’s low rates of prosocial imitation in a transgressor context to their high rates in a bystander context in this investigation and our previous study (Williamson, Donohue & Tully, 2013) adds to mounting evidence (e.g., Donohue et al., 2019) that the transgressor context is clearly distinct from a bystander context and is developmentally important. Indeed, whether or not children are at fault for causing a victim’s distress appears to greatly affect children’s prosocial responding and perhaps their emotions. Existing studies have tended to make claims about both reparative and prosocial behaviors based on designs that almost exclusively examine children’s prosocial responding in bystander contexts. The current studies underscore that investigations must specifically examine children’s responses to transgressions rather than assuming that findings from bystander contexts will generalize to transgressor contexts.

Limitations

Limitations of these studies should be noted. Children were assessed at one time point only, leaving questions about children’s imitation after repeated exposure to prosocial demonstrations—which is how learning typically occurs in the natural environment—that cannot be answered by the current studies. Similarly, raters could not be completely blind to condition because the content of the coded test period differed depending on condition (i.e., one condition involved a neutral interaction rather than transgressions). The sample was predominantly Caucasian; studies with samples of differing demographic characteristics will be important for understanding the generalizability of these findings. Relatedly, the sample was from a Western industrialized culture. It will be important to test the effect of modeling on prosocial imitation across cultures, particularly given that cross-cultural research on prosocial behaviors has revealed some universalities but also cultural differences (e.g., Chernyak, Harvey, Tarullo, Rockers, & Blake, 2018) and that existing cross-cultural studies have examined instrumental helping and sharing rather than comforting behaviors. Finally, future studies should replicate the results by examining bystander and transgressor contexts in the same study (i.e., same sample of children).

Conclusions

The current investigation found that toddlers can learn a novel prosocial behavior from a very general prosocial demonstration and apply this knowledge to help their parent in a very specific distress scenario. Whereas there was a large effect of modeling on toddlers’ prosocial behaviors in a bystander context, there was no effect in a transgressor context in which children were led to believe that they caused the distress. As transgressors, toddlers exclusively relied on previously learned prosocial behaviors, perhaps because they knew these strategies were previously effective. Overall, this investigation suggests that whether or not children are at fault for causing their parent’s distress greatly influences the prosocial strategies they use to alleviate the distress.

Acknowledgments

The work of Dr. Donohue was supported by a Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) fellowship (D40HP19643; primary investigator: Cohen) and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant (T32 MH100019; primary investigators: Luby & Barch). We thank the families who participated in the study and the research assistants who assisted with coding.

References

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 82 (2), 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KC, Zahn-Waxler C, & Cole PM (1993). Avoiders vs amenders: Implications for the investigation of guilt and shame during toddlerhood?. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 481–505. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Svetlova M, Anderson R, Nichols SR, & Drummond J (2013). Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parents’ talk about emotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy, 18, 91–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Nagell K, Tomasello M, Butterworth G, & Moore C (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63 (4, Serial No. 255). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak N, Harvey T, Tarullo AR, Rockers PC, & Blake PR (2018). Varieties of young children’s prosocial behavior in Zambia: The role of cognitive ability, wealth, and inequality beliefs. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Satlof-Bedrick ES, Hammond SI, Drummond JK, Waugh WE, & Brownell CA (2017). Explicit scaffolding increases simple helping in younger infants. Developmental Psychology, 53, 407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Zahn-Waxler C, Roth-Hanania R, & Knafo A (2013). Concern for others in the first year of life: Theory, evidence, and avenues for research. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue MR, Tillman R, & Luby JL (2019). Early socioemotional competence, psychopathology, and latent class profiles of reparative prosocial behaviors from preschool through early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419000397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue MR, & Tully EC (2019). Reparative prosocial behaviors alleviate children’s guilt. Developmental Psychology, 55, 2102–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KA (2014). A construct divided: Prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KA, & Kuhlmeier VA (2013). Classifying prosocial behavior: Children’s responses to instrumental need, emotional distress, and material desire. Child Development, 84, 1766–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, & Brown J (1994). Affect expression in the family, children’s understanding of emotions, and their interactions with others. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40, 120–137. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Brown J, Slomkowski C, Tesla C, & Youngblade L (1991). Young children’s understanding of other people’s feelings and beliefs: Individual differences and their antecedents. Child Development, 62, 1352–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, & Fabes RA (1998). Prosocial development In Damon W & Eisenberg N (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 701–778). New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ely R, & Gleason JB (2006). I’m sorry I said that: Apologies in young children’s discourse. Journal of Child Language, 33, 599–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazzani I, Ornaghi V, Agliati A, & Brazzelli E (2016). How to foster toddlers’ mental-state talk, emotion understanding, and prosocial behavior: A conversation-based intervention at nursery school. Infancy, 21, 199–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD (2007). The socialization of prosocial development In Grusec JE & Hastings PD (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 638–664). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Zahn-Waxler C, Robinson J, & Usher B (2000). The development of concern for others in children with behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 36, 531–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, & Cook KV (2007). The transformation of prosocial behavior from infancy to childhood In Brownell CA & Kopp CB (Eds.), Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations (pp. 100–131). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hayne H, Herbert J, & Simcock G (2003). Imitation from television by 24- and 30-month-olds. Developmental Science, 6, 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G (1991). Socialization and temperament in the development of guilt and conscience. Child Development, 62, 1379–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Gross JN, Lin M-H, & Nichols KE (2002). Guilt in young children: Development, determinants, and relations with a broader system of standards. Child Development, 73, 461–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, & Ramsay D (2002). Cortisol response to embarrassment and shame. Child Development, 73, 1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF, & Ritz EG (1984). Patterns of gestural, vocal, and verbal imitation performance in infancy. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 30, 369–392. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff AN (1988). Infant imitation after a 1-week delay: Long-term memory for novel acts and multiple stimuli. Developmental Psychology, 24, 470–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantel-Vivier A, Pihl RO, Côté S, & Tremblay RE (2014). Developmental association of prosocial behaviour with aggression, anxiety and depression from infancy to preadolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M (2006). Copying actions and copying outcomes: Social learning through the second year. Developmental Psychology, 42, 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Simcock G, & Jenkins L (2008). The effect of social engagement on 24-month-olds’ imitation from live and televised models. Developmental Science, 11, 722–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornaghi V, Brazzelli E, Grazzani I, Agliati A, & Lucarelli M (2017). Does training toddlers in emotion knowledge lead to changes in their prosocial and aggressive behavior toward peers at nursery?. Early Education and Development, 28, 396–414. [Google Scholar]

- Over H, & Carpenter M (2012). Putting the social into social learning: Explaining both selectivity and fidelity in children’s copying behavior. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 126, 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettygrove DM, Hammond SI, Karahuta EL, Waugh WE, & Brownell CA (2013). From cleaning up to helping out: Parental socialization and children’s early prosocial behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 36, 843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP (1975). Generosity in children: Immediate and long-term effects of modeling, preaching, and moral judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmacher N, Collard J, & Kärtner J (2017). The Differential role of parenting, peers, and temperament for explaining interindividual differences in 18-months-olds’ comforting and helping. Infant Behavior and Development, 46, 124–134. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub E (1970). A child in distress: The effect of focusing responsibility on children on their attempts to help. Developmental Psychology, 2, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols SR, & Brownell CA (2010). Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping: Toddlers’ prosocial behavior. Child Development, 81, 1814–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, & Mashek DJ (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman-Osborne C, Cole DA, & Felton JW (2010). Definition and measurement of guilt: Implications for clinical research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A (2018). The prosocial functions of early social emotions: The case of guilt. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Carpenter M, & Tomasello M (2009). Sympathy through affective perspective taking and its relation to prosocial behavior in toddlers. Developmental Psychology, 45, 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volbrecht M, Lemery-Chalfant K, Aksan N, Zahn-Waxler C, & Goldsmith H (2007). Examining the familial link between positive affect and empathy development in the second year. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168, 105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Want SC, & Harris PL (2002). How do children ape? Applying concepts from the study of non-human primates to the developmental study of “imitation” in children. Developmental Science, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, & Tomasello M (2013). Parental presence and encouragement do not influence helping in young children. Infancy, 18, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson RA, Donohue MR, & Tully EC (2013). Learning how to help others: Two-year-olds’ social learning of a prosocial act. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114(4), 543–550. 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Cole PM, Welsh JD, & Fox NA (1995). Psychophysiological correlates of empathy and prosocial behaviors in preschool children with behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, & King RA (1979). Child rearing and children’s prosocial initiations toward victims of distress. Child Development, 50, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, Wagner E, & Chapman M (1992). Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 28, 126–136. [Google Scholar]